Stealth Acquisitions and Product Market Competition

ABSTRACT

We examine whether and how firms structure their merger and acquisition deals to avoid antitrust scrutiny. There are approximately 40% more mergers and acquisitions (M&As) than expected just below deal value thresholds that trigger antitrust review. These “stealth acquisitions” tend to involve financial and governance contract terms that afford greater scope for negotiating and assigning lower deal values. We also show that the equity values, gross margins, and product prices of acquiring firms and their competitors increase following such acquisitions. Our results suggest that acquirers manipulate M&As to avoid antitrust scrutiny, thereby benefiting their own shareholders but potentially harming other corporate stakeholders.

A core mission of regulators in most countries is to prevent anticompetitive practices that harm consumers. To carry out this mandate in the United States, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) conduct extensive reviews to evaluate the potential impact of corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&As) on competition. Concerns about the increasing incidence of anticompetitive M&As motivated the adoption of the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, which established a pre-merger notification threshold that requires parties to notify the DOJ and FTC of their intent to merge if their deal is above a specified value.1 Recent adjustments to the threshold rule mean that the vast majority of M&As now go without antitrust review (e.g., Wollmann (2019)).2 Thus, although a key purpose of M&As is to achieve productivity improvements for acquirers or synergies between acquirers and targets (e.g., David (2021)), many questions remain about the potential anticompetitive effects of M&As that are not subject to regulatory scrutiny.

A long line of corporate finance research examines the role of M&As in creating or destroying shareholder value (see, e.g., Eckbo (1983), Schipper and Thompson (1983), Asquith (1983), Agrawal, Jaffe, and Mandelker (1992)), and suggests that one important way M&As create value for shareholders is by consolidating the acquirer's industry to increase the firm's own market power (e.g., Hoberg and Phillips (2010a), Fathollahi, Harford, and Klasa (2021)). Such increases in market power can be substantial and potentially harmful to other corporate stakeholders—especially consumers—and thus are precisely the reason that antitrust regulators pay close attention to the competitive effects of M&As. Accordingly, prior literature typically assumes that firms conduct their M&As seeking regulatory approval for a given deal under the confines of the current antitrust regime. However, this literature assumes away the possibility that firms can actively circumvent the regulatory rules for screening of anticompetitive deals.

In this paper, we study whether firms engage in “stealth acquisitions,” that is those deliberately negotiated and structured to assign deal values that fall “just below” the regulatory notification threshold. We find a substantial number of stealth acquisitions whereby firms manipulate the terms of their M&A financial and governance contracts to avoid oversight and review by antitrust regulators. These acquisitions, while beneficial to shareholders of the acquiring firm, have broader stakeholder implications by inducing anticompetitive effects that can harm other corporate stakeholders (e.g., target shareholders and consumers).

The question of acquirers systematically circumventing antitrust rules is not only of academic interest to financial economists. Reflecting concerns about stealth acquisitions, the FTC recently launched initiatives aimed at understanding the anticompetitive effects of nonreportable deals (FTC (2020)).3 For example, in 2020 the FTC launched antitrust investigations into all nonreportable acquisitions since 2010 by five of the leading U.S. technology firms—Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft—due to concerns that many of these deals had anticompetitive consequences (e.g., Kamepalli, Rajan, and Zingales (2021)). These regulatory concerns extend beyond the technology sector, as stealth acquisitions in nontechnology industries could have more direct consequences for other stakeholders in terms of increased product prices for consumers. Yet little is known about whether acquirers across industries systematically structure deals to evade the notice of resource-constrained antitrust regulators and, if so, how these stealth acquisitions are structured and the extent to which these deals impact product market competition. This paper attempts to fill this gap.

Using data on all M&A transactions for U.S. firms between 2001 and 2019, we first document evidence of a discontinuity around the pre-merger notification threshold. Specifically, we find a 28% to 45% higher-than-expected number of deals “bunching” immediately below the threshold that would trigger antitrust review.4 We refer to these potentially manipulated deals as “stealth acquisitions.” If scrutinized by antitrust regulators, these stealth acquisitions would increase the number of Second Requests by 4% to 6%.5 We further find that bunching of M&As just below the threshold does not occur when we examine other M&A deals whose values are further away from the threshold that would trigger antitrust review, when we focus exclusively on acquisitions in industries that are always exempt from the pre-merger notification program (i.e., hotels and real estate; FTC (2008)), and when we assess deal discontinuity based on the next year's notification threshold. Evidence of significant M&A activity just below the threshold, together with the absence of such a discontinuity in the “falsification tests” suggests that some acquirers deliberately manage the size of their deals to avoid antitrust review.

We next conduct several tests to better understand the characteristics of the targets and acquirers engaging in these stealth acquisitions. First, consistent with concerns that large public companies find ways to make reportable transactions nonreportable, we find that acquisitions involving public firms acquiring smaller private targets are 31.3% more likely to occur just below the threshold. We also find that financial contracts incorporating earnouts, which allow managers of acquiring firms to exercise discretion in the methods used to assign deal values so that they fall just below the deal-size threshold, are more likely in these just-below acquisitions. In addition, we find that deals involving acquirers that extend the directors and officers (D&O) insurance coverage of private target firms or that agree to higher post-acquisition breach-of-terms deductible thresholds, both of which can allow acquirers to negotiate lower deal values, are more likely to be just below the threshold. Consistent with these lower deal values being actively managed to avoid antitrust review, we find that public acquirers pay lower deal premiums for private targets in acquisitions that fall just below the threshold.

One might wonder why, in equilibrium, managers of target firms are willing to accept values that are manipulated to fall below the threshold. We conduct several tests that provide insights into why target firm managers would be willing to make such decisions. First, we find that deals involving cash payments, which reduces the exposure of targets to risk associated with the post-acquisition stock holding requirements of U.S. securities laws, are 28% more likely to be just-below deals. Second, consistent with concerns that acquirers can take advantage of target shareholders by providing private benefits to target CEOs in exchange for lower deal values (e.g., Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny (1988), Fich, Cai, and Tran (2011)), we find that deals with governance contracts that employ target CEOs post-acquisition are more likely to be stealth acquisitions, and in such cases earnout provisions are 6% more likely to pay off. These findings suggest that acquirers compensate target firms and their managers for lower deal values with implicit and explicit benefits in financial and governance contracts to facilitate deal values that fall below the threshold that otherwise would have triggered antitrust review.

Next, we study the economic incentives of acquirers to negotiate and assign lower deal values to avoid antitrust scrutiny. We expect deals involving acquirers with incentives to coordinate with their targets—for example, acquisitions in concentrated industries, which are typically of greater concern to antitrust regulators due to their potential to harm consumers (Gowrisankaran, Nevo, and Town (2015), Wollmann (2019), Eliason et al. (2020))—are more likely to fall just below the pre-merger review threshold. Consistent with this expectation, we find that the discontinuity is largely due to acquirers with the strongest incentives to coordinate with their targets, that is, rivals from the same industry. We also find that this relation is more pronounced for deals that involve acquirers and targets in the same geographic area and deals in more concentrated industries. Together, these findings suggest that deals likely to have anticompetitive effects that are harmful to consumers tend to be structured as stealth acquisitions that narrowly avoid antitrust review.

We conduct several tests to examine whether stealth acquisitions benefit acquiring firms’ shareholders at the cost of other stakeholders such as consumers through reduced product market competition. Prior studies argue that certain patterns in the returns of industry rivals around a merger are indicative of reduced product market competition. In particular, benefits of mergers that only provide synergies to the acquirer should not propagate to rival firms, while benefits from mergers that result in increases in product market prices should (e.g., Eckbo (1983), Stillman (1983), Chevalier (1995a), Fathollahi, Harford, and Klasa (2021)). Consistent with the anticompetitive nature of stealth acquisitions, we find that public announcements of just-below mergers are associated with 12.5% higher abnormal returns for rival firms when such acquisitions are horizontal in nature, that is between direct competitors operating in the same industry, relative to announcements of horizontal mergers that are just above the threshold. We also examine changes in the gross margins of acquirers and their industry rivals and find a 1.1-percentage-point increase in industry-average gross margins in the year after horizontal acquisitions falling just below the threshold compared to horizontal acquisitions just above the threshold.

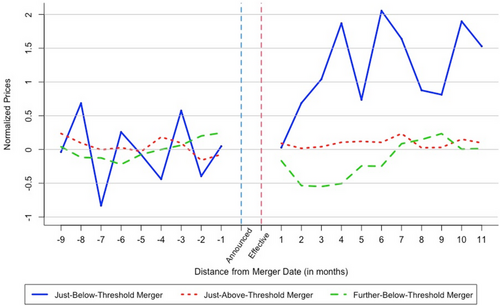

As a direct test of the impact of stealth acquisitions on consumers, we narrow our focus to three acquisitions during our sample period—one just below, one just above, and one well below the pre-merger deal value threshold—by horizontal rivals in the consumer products industry. This analysis, which employs product-level prices for the acquirer and rivals that share common products with the targets, is based on the idea that product pricing patterns of industry rivals following events that reduce product market competition can help identify anticompetitive behavior (e.g., Chevalier (1995b), Azar, Schmalz, and Tecu (2018)). Consistent with reduced product market competition, we find an increase in average monthly product prices for product market rivals’ common products following our stealth acquisition of interest, while we find no change in prices for the just-above or well-below deals.

We conduct several additional tests to assess the robustness of our results and consider potential alternative explanations. Our results are robust to alternative bin sizes, do not hold for several definitions of already-exempt mergers, are robust to alternative fixed effect structures (e.g., industry-year), and are robust to alternative definitions of “horizontal” mergers (e.g., Hoberg and Phillips (2016)). When we consider several nonmutually exclusive alternative explanations for our inferences, we do not find evidence that the bunching we find below the threshold is driven by (i) acquirers’ incentives to delay merger announcements until the subsequent year, (ii) mergers that are already exempt under alternative thresholds (i.e., the “size-of-person” test), or (iii) firms avoiding Second Requests from antitrust authorities for innocuous reasons.

Our study makes three contributions to the broad literature on the role of M&As in product market competition. First, we contribute to the emerging literature on the relation between antitrust enforcement screening and M&A activity. Although newly exempt horizontal deals increased following a change to the notification screening thresholds (Wollmann (2019, 2020)), our study highlights differences in and potential manipulation of the contracts of deals that fall just below the threshold. In particular, we show that firms can structure M&As to avoid antitrust scrutiny and reduce competition by exploiting regulators’ monitoring resource constraints at the expense of target shareholders and consumers. Although prior literature typically assumes that managers extract private benefits from shareholders alone, our study adopts a broader stakeholder governance perspective to shed light on the possibility of managers extracting private benefits from other, nonshareholder stakeholders such as consumers.

Our study also contributes to the literature on the interaction between corporate finance and product market competition—for example, Eckbo (1983, 1992), Chevalier (1995a, b), Sheen (2014), Wollmann (2020), Eliason et al. (2020), Fathollahi, Harford, and Klasa (2021)—by providing initial evidence on whether and how acquirers intentionally structure deals to avoid antitrust enforcement and reduce product market competition. A concurrent study by Wollmann (2020) on mergers in the U.S. kidney dialysis sector does not find bunching of M&A deal values around the notification thresholds, and attributes this result to the legal risk associated with intentional avoidance of notifications. In related work, Cunningham, Ederer, and Ma (2021) show that incumbent pharmaceutical firms acquire innovative targets solely to “kill” their projects, and that some of these deals fall just below the threshold for pre-merger review, but they do not examine how these deals are structured to avoid antitrust scrutiny. Our study contributes to this recent literature by documenting the explicit financial and governance contracting mechanisms that are used to manipulate deal values. Given the effects of these deals on nonshareholder stakeholders such as consumers, future research at the intersection of corporate finance and antitrust regulation can play a particularly important role in informing academic and policy debates about shareholder- versus broader stakeholder-based corporate governance (e.g., Bebchuk (2004, 2005), Edmans (2021)).

Finally, our study contributes to the industrial organization literature on the evolution and regulation of competition (e.g., Shahrur (2005), Azar, Schmalz, and Tecu (2018), Wollmann (2019), De Loecker, Eeckhout, and Unger (2020)). Our evidence suggests that concerns about the limited efficacy of sharp pre-merger review guidelines are warranted (e.g., Rose and Sallet (2020)), as a conspicuous number of firms appear to manipulate their deal size to circumvent regulatory review, potentially harming consumers. Moreover, while our focus on M&As around this threshold is well-suited to identify bunching as evidence of deal manipulation, our findings likely extend to M&As around other filing thresholds and regulations. Therefore, if anything, our estimates likely underestimate the frequency and impact of M&A antitrust regulation avoidance.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section I discusses institutional features of antitrust regulation for M&A deals and related academic literature. Section II describes our sample and key variables. Section III presents results on the existence of and contracting for stealth acquisitions. Section IV presents results on the effects of stealth acquisition on product market competition. Section V provides concluding remarks.

I. Institutional Background and Related Literature

A. Antitrust Regulation and M&As

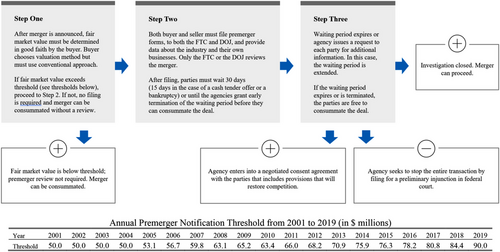

Competition law in the United States places strict limits on the ability of M&A deals to impact industry competition. For instance, Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits M&As “in any line of commerce or in any activity affecting commerce in any section of the country, [where] the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” Moreover, Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits “unfair” methods of competition. To enforce these regulatory objectives, the antitrust division of the DOJ and the FTC rely on the HSR Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976 to review potential anticompetitive effects of M&A deals before they take place. The filing of the pre-merger notification report allows regulators up to 30 days to perform a review of whether the proposed transaction will adversely affect U.S. commerce under antitrust laws.6 Figure 1 illustrates the FTC's typical pre-merger review notification process and potential outcomes of this process on an M&A deal's ability to proceed.

Although the HSR Act initially required notification filings on all transactions that exceeded a threshold of $15 million, in 2000 Congress significantly amended this size-of-transaction threshold to apply only to transactions with a deal value above $50 million.7 The rationale for exempting deals with a value below $50 million was that such transactions were unlikely to raise substantive antitrust concerns. In which case requiring notifications for smaller deals may impose an unnecessary burden on firms and/or weaken regulators’ monitoring capacity, costs that can exceed the social welfare or efficiency benefits from identifying competitive issues from small deals.8

The adjustment to the size of the transaction threshold had a dramatic effect on pre-merger notifications. Notably, while the number of annual notifications increased by around 33% in the three-year period leading up to the 2000 size-of-transaction threshold amendment, notifications fell by 79% in the three years immediately following the amendment (FTC (2004)). Recent evidence suggests that the increase in the size-of-transaction threshold increased the prevalence of horizontal mergers between firms in the same industry. For instance, Wollmann (2019) estimates that the decade following the threshold increase witnessed up to 324 additional horizontal mergers per year that collectively involved the acquisition of targets worth a total of $53 billion in annual revenue. Further, while the general authority granted to FTC and DOJ under Sections 6 (b), 9, and 20 of the FTC Act and Section 1312 of the United States Code on Commerce and Trade permits them to retrospectively investigate nonreportable transactions, Wollmann (2019) shows that mergers that are newly exempted from the pre-merger notification requirement are less likely to be subject to regulatory investigation after the M&A deal is executed. These observations give rise to concerns that smaller nonreportable M&A deals can also raise competitive issues that violate antitrust statutes.

Concerns over antitrust risk from small deals are further supported by anecdotal evidence of higher financial gains that acquirers realize from such deals. For example, a study conducted by McKinsey & Company indicates that firms that adopt a systematic approach to M&As through the use of an increased number of small deals are able to accrue more market capitalization relative to peers that focus on larger deals and selective acquisitions (Rudnicki, Siegel, and West (2019)). These concerns have led antitrust regulators to question the potential anticompetitive effects arising from nonreportable M&A transactions. For instance, in a 2014 speech, DOJ Deputy Assistant Attorney General Overton noted that potential harm to consumers is unlikely to be captured by the size of the transaction or by merging party market values (DOJ (2014)), and he elaborated on how nonreportable transactions could give rise to antitrust concerns, including harm to consumers in regional markets, adverse effects on the market for a key input to a downstream product, and reduced competition in a narrow product market that still creates broader or national issues (e.g., impair the quality of voting equipment systems).

Consistent with these regulatory concerns, antitrust challenges against nonreportable transactions have increased significantly in recent years (e.g., Mason and Johnson (2016)). Moreover, in February 2020, the FTC issued an order under Section 6(b) of the FTC Act to formally launch its own antitrust investigations into every nonreportable acquisition made by five of the leading U.S. technology firms—Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook—dating as far back as 2010.9 The FTC stated that its probe would help it understand “whether large tech companies are making potentially anticompetitive acquisitions of nascent or potential competitors that fall below HSR filing thresholds” and reform its policies to promote competition and protect consumers. Subsequent statements released by FTC commissioners Rohit Chopra and Christine Wilson questioned the sufficiency of the HSR notification process in other industries and called for studies across a broader range of industries to gain a better understanding of the competitive effects of nonreportable mergers (Wilson and Chopra (2020)).

B. Related Literature

Although it is illegal for firms to engage in business practices that harm competition under Section 7 of the Clayton Act, a large body of industrial organization research studies firms’ incentives to engage in anticompetitive behavior (e.g., Stigler (1964), Harrington and Skrzpacz (2011)). Within this literature, several studies examine how lax M&A antitrust enforcement in the pharmaceutical industry leads to an increase in anticompetitive mergers and worse product market outcomes for consumers in terms of higher product prices (e.g., Eliason et al. (2020)).10 Furthermore, Cunningham, Ederer, and Ma (2021) provide evidence that this result is due in part to large acquirers amassing firms with similar research projects and terminating overlapping innovation—that is, risky pharmaceutical drug projects—of targets. These studies examine whether certain M&A deals have anticompetitive effects, but do not examine how firms achieve such anticompetitive M&A deals in the first place.

Building on this literature, a burgeoning corporate finance literature explores the broader relation between anticompetitive behavior and corporate finance practices. For example, Eckbo (1992) and Shahrur (2005) find that horizontal mergers tend to be bad for consumers and that rents accrue to all firms in an industry following horizontal M&A deals, consistent with recent evidence on firms’ efforts to more easily navigate the FTC's antitrust review process (e.g., Mehta, Srinivasan, and Zhao (2020)). More recently, Dasgupta and Žaldokas (2019) find that increases in the cost of explicit collusion lead to more M&A activity and equity issuances, and Azar, Schmalz, and Tecu (2018) provide evidence from the U.S. airline industry that a common ownership structure can lead to anticompetitive pricing strategies.

Our study contributes to these growing corporate finance and economics literatures by identifying (i) evidence of firms manipulating the size of their M&A deals to avoid antitrust scrutiny as a novel channel through which firms avoid regulatory scrutiny, (ii) the financial contracting characteristics of these stealth acquisition deals that facilitate regulatory avoidance, (iii) heterogeneous industry and market conditions that incentivize firms to participate in stealth acquisitions, and (iv) the impact of these stealth acquisitions on competition among firms’ product market rivals. In these regards, our study is the first to examine firms’ avoidance of antitrust regulation by manipulating the size of their deals, and offers novel evidence that such avoidance is detrimental to consumers.

II. Data and Descriptive Statistics

A. Data Sources and Key Variables

Our initial sample comes from all completed and terminated U.S. M&As involving public and private targets and acquirers announced from January 2001 to February 2020 on the Thomson Securities Data Company (SDC) Mergers and Acquisitions database. Following Moeller, Schlingemann, and Stulz (2005), we exclude deals below $1 million. We also discard all deals involving targets that are financial firms (SICs 6000 to 6999) or regulated utilities (SICs 4900 to 4999), as M&As of these types are subject to industry-specific merger regulation that is unrelated to our analysis. Finally, we exclude deals involving the acquisition of hotels and motels (SIC 7011), as these acquisitions are always exempt from pre-merger review (FTC (2008)). This selection process, presented in Panel A of Table I, yields a final sample of 19,886 deals with nonmissing acquirer and target firm data for the key variables in our analyses. We use this sample of deals to test for a discontinuity in M&As around the pre-merger review threshold and assess the types of firm and deal characteristics involved in stealth acquisitions.

| This table presents the sample selection procedure for the full sample of M&As (Panel A) and for the near-threshold sample of M&As (Panel B). The sample is constructed using the universe of deals from the Securities Data Company (SDC) Mergers and Acquisition database announced between February 1, 2001 and February 27, 2020. In addition, Panel C presents the top 10 industries in our full sample of 19,886 deals, using Fama-French 48-industry classifications, Panel D presents the comparable distributions for the top 10 industries in two subsamples representing deals with transaction values that are within 10% of the annual FTC notification threshold, that is deal values that are either ≥0% but ≤10% below the threshold or >0% but ≤10% above the threshold (i.e., just-below-threshold deals and just-above-threshold deals, respectively). Panel B presents the top 10 industries separately for below- and above-threshold deals. | |

|---|---|

| Panel A: Sample Selection (Full Sample) | |

| All U.S. public and private M&As (>$1 mil.) from February 1, 2001 to February 6, 2020 | 34,839 |

| Less: Deals with missing data on % acquired, % owned before, or % owned after | (6,225) |

| Less: Deals involving financial firms or utilities | (7,212) |

| Less: Deals involving real property for rental or investment purposes, or hotels | (1,495) |

| Less: Deals when acquirer purchases remaining interest of its own subsidiary | (21) |

| Full sample of deals | 19,886 |

| Panel B: Near-Threshold Sample | |

|---|---|

| Just-above-threshold M&As | 274 |

| Just-below-threshold M&As | 366 |

| Sample of near-threshold deals | 640 |

| Panel C: Industry Distribution (Top Ten Industries) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fama-French 48-Industry Groups | Number of Deals | Percentage of All Deals |

| Top 10 | ||

| Business services | 6,417 | 32.27 |

| Pharmaceutical products | 1,305 | 6.56 |

| Healthcare | 1,012 | 5.09 |

| Electronic equipment | 991 | 4.98 |

| Wholesale | 776 | 3.90 |

| Retail | 753 | 3.79 |

| Medical equipment | 716 | 3.60 |

| Communication | 665 | 3.34 |

| Computers | 570 | 2.87 |

| Transportation | 503 | 2.53 |

| Total (Top 10) | 13,708 | 66.40 |

| Panel D: Industry Distribution (Within ±10% of Annual Threshold) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Just-Below Threshold | Just-Above Threshold | |||

| Fama-French 48-Industry Groups | Number of Deals | Percentage of Deals “Below” | Number of Deals | Percentage of Deals “Above” |

| Top 10 | ||||

| Business services | 123 | 33.61 | 93 | 33.94 |

| Pharmaceutical products | 22 | 6.01 | 17 | 6.20 |

| Electronic equipment | 22 | 6.01 | 11 | 4.01 |

| Medical equipment | 20 | 5.46 | 13 | 4.74 |

| Retail | 18 | 4.92 | 15 | 5.47 |

| Healthcare | 13 | 3.55 | 16 | 5.84 |

| Wholesale | 13 | 3.55 | 7 | 2.55 |

| Personal services | 12 | 3.28 | 7 | 2.55 |

| Computers | 12 | 3.28 | 13 | 4.74 |

| Construction | 10 | 2.73 | 3 | 1.09 |

| Total (Top 10) | 265 | 72.40 | 195 | 71.13 |

We also examine the financial contracting terms, incentives, and product-level prices for stealth acquisitions. Although we rely on the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and SDC for data to construct many of our key variables, data to capture other deal provisions important to our study (e.g., earnouts, deal premiums for private targets, provisions for extended D&O coverage, and post-closing deductible thresholds) are collected by reading through merger-related financial contract disclosures found in EDGAR 8-K, 10-Q, and 10-K public filings. For tests that require extensive hand collection, we restrict our test sample to 640 deals that fall just below and above the pre-merger notification thresholds, presented in Panel B of Table I. Our data collection process is detailed in the Internet Appendix.11

B. Descriptive Statistics

Panel C of Table I shows that the top 10 industries represented in our full sample account for almost 70% of M&A deals, with the largest number of deals (around 30% of all deals) completed by acquirers in the business services industry. Panel D of Table I presents the comparable distributions for the top 10 industries in two subsamples representing deals with transaction values that are within 10% of the annual FTC notification threshold—that is, deal values that are either ≥0% but ≤10% below the threshold, or > 0% but ≤10% above the threshold (just-below-threshold deals and just-above-threshold deals, respectively). We find that the top 10 industries in these two subsamples consist of the same industries in Panel C, with the exception of the personal services industry and the construction industry, indicating that the mix of deals that occur near the pre-merger notification threshold is similar to the mix across all M&A deals. Further, the two subsamples are similar to each other and the full sample on the distribution of observations across industries (e.g., business services accounts for 33% to 34% of observations). The absence of any industry being overrepresented in the subsample of deals that are within 10% below the threshold suggests that the scrutiny of deals by DOJ/FTC does not appear to vary significantly across industries in a manner that produces a greater concentration of below-threshold deals in certain industries.

Panel A of Table II presents descriptive statistics on the variables used in our main empirical analyses. We find that the average deal value of acquisitions in our full sample is approximately $400 million (DealValue) and that roughly 77% of deals involve a private target (PrivateTarget).

| This table presents the distribution of key variables used in our analysis. All variables are defined in Appendix A. Panel A presents descriptive statistics for all variables for both the pooled and the near-threshold analysis, and Panel B presents descriptive statistics for key variables in the near-threshold analysis (split by below versus above the pre-merger review threshold). *, **, *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Key Variables (Pooled and Near-Threshold Analysis) | ||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | 25th | Median | 75th |

| Deal analysis | ||||||

| PublicAcquirer | 19,886 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| PrivateAcquirer | 19,886 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PublicTarget | 19,886 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Public-Public | 19,886 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Public-Private | 19,886 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Private-Private | 19,886 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Private-Public | 19,886 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AllCash | 19,886 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| AllStock | 19,886 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AllCashandOther | 19,886 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| AllStockandOther | 19,886 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Horizontal | 19,886 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Intrastate | 19,886 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Earnouts | 19,886 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| EarnoutPerc | 19,886 | 3.60 | 13.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AcqTermFeePercent | 19,886 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PublicTargetDealPremium | 3,642 | 64.58 | 456.29 | 14.34 | 31.46 | 54.28 |

| EconomicTie | 603 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| PrivateTargetDealPremium | 222 | 55.74 | 22.84 | 40.63 | 57.21 | 73.40 |

| EarnoutPayoff | 45 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Financial contracting analysis | ||||||

| ExtendedLiabilityCoverage | 234 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| DeductibleThreshold | 192 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.50 |

| Returns and gross margin analysis | ||||||

| RivalRet | 594 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| ∆ GrossMargin | 364 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Product pricing analysis | ||||||

| NormalizedPrice | 1,915,291 | 0.05 | 1.02 | −0.70 | 0.00 | 0.71 |

| JustBelowThreshold | 1,915,291 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Post | 1,915,291 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Product pricing analysis | ||||||

| Below-Threshold | ||||||

| Price | 77,835,861 | 6.46 | 3.31 | 3.99 | 5.67 | 8.09 |

| CommonProduct | 77,835,861 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Post | 77,835,861 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Above-Threshold | ||||||

| Price | 4,091,337 | 19.65 | 25.16 | 6.79 | 9.99 | 23.74 |

| CommonProduct | 4,091,337 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Post | 4,091,337 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Further-Below-Threshold | ||||||

| Price | 4,760,492 | 3.64 | 0.91 | 3.00 | 3.69 | 3.99 |

| CommonProduct | 4,760,492 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Post | 4,760,492 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Controls | ||||||

| DealValue | 19,886 | 400.33 | 2,625.67 | 7.50 | 26.00 | 120.00 |

| TenderOffer | 19,886 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PrivateTarget | 19,886 | 0.77 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| NumRivals | 594 | 40.54 | 55.77 | 4.00 | 14.00 | 49.00 |

| RepsSurvive | 232 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SurvivalPeriod | 222 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.50 |

| TargetTermFeePercent | 19,886 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Panel B: Near-Threshold Sample (±10% of Threshold) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Just-Below Threshold | Just-Above Threshold | |||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | Median | N | Mean | Median | Diff. in Means | Diff. in Medians |

| Deal analysis | ||||||||

| PublicAcquirer | 366 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 274 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PrivateAcquirer | 366 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.13 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.00 |

| PublicTarget | 366 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.23 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.00 |

| Public-Public | 366 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.12 | 0.00 | −0.04* | 0.00* |

| Public-Private | 366 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 274 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Private-Private | 366 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| Private-Public | 366 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| AllCash | 366 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| AllStock | 366 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.05** | 0.00*** |

| AllCashandOther | 366 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 274 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.09** | 0.00*** |

| AllStockandOther | 366 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.47 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| Horizontal | 366 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Horizontal(Continuous) | 366 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 274 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.08** | 0.18** |

| Intrastate | 366 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.20 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.00 |

| Earnouts | 366 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.05* | 0.00* |

| EarnoutPerc | 366 | 4.62 | 0.00 | 274 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 1.05 | 0.00 |

| AcqTermFeePercent | 366 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00** | −0.00** |

| PublicTargetDealPremium | 50 | 93.46 | 47.36 | 51 | 65.62 | 49.05 | 27.84 | −1.69 |

| PrivateTargetDealPrem | 133 | 55.00 | 56.60 | 89 | 56.87 | 56.60 | −1.87 | 0.00 |

| EconomicTie | 343 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 260 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 0.12*** | 0.00*** |

| EarnoutPayoff | 28 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 17 | 0.76 | 1.00 | −0.12 | 0.00 |

| Financial contracting analysis | ||||||||

| ExtendedLiabilityCoverage | 123 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 111 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| DeductibleThreshold | 105 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 87 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.12** | 0.18 |

| Returns and gross margin analysis | ||||||||

| RivalRet | 344 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 250 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ∆GrossMargin | 206 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 158 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| Controls | ||||||||

| DealValue | 366 | 59.35 | 58.27 | 274 | 66.66 | 65.13 | −7.31*** | −7.86*** |

| TenderOffer | 366 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| RepsSurvive | 122 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 110 | 0.56 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| SurvivalPeriod | 116 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 106 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| TargetTermFeePct | 366 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 274 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00* |

| NumRivals | 344 | 39.66 | 14.00 | 250 | 41.76 | 13.50 | −2.10 | 0.50 |

Panel B of Table II illustrates how the acquirer, target, and deal attributes vary across the two restricted subsamples of just-above- and just-below-threshold deals. Although the statistical difference between the values of deals (DealValue) involving just-above- and just-below-threshold targets is expected, the mean difference amounts to only $7.31 million, which is small relative to the general variance of deal values in our full sample (standard deviation = $2.6 billion). This implies that deals just above and just below the threshold are in essence fundamentally similar, as suggested by the insignificant differences in the values of nearly all of the other variables across the two subsamples of firms. We find some evidence of greater use of earnouts (Earnouts) and cash and other nonstock payments (AllCashandOther), as well as lower use of all-stock financing (AllStock), in just-below-threshold deals. Moreover, acquirers in deals that are just below the threshold are more likely to have a future economic tie with a target CEO (EconomicTie).

III. Characteristics of Stealth Acquisitions

This section examines three features of stealth acquisitions. First, we examine the existence and prominence of stealth acquisitions by assessing the frequency of deals occurring just below relative to just above the pre-merger review notification threshold. The advantage of this approach is that it focuses on a narrow subset of deals in close proximity to the threshold, deals for which merger activity and attributes of the acquirers and targets involved should be similar. Second, we examine differences in deal and financial contract characteristics for M&A deals occurring just below relative to just above the pre-merger review notification threshold. These tests allow us to identify the types of deals that most often bunch just below as well as the financial and implicit contracting mechanisms that facilitate acquirers’ ability to manipulate deal values to below-notification levels. Finally, we investigate whether stealth acquisitions are more likely to consist of deals that can lead to anticompetitive outcomes. Together, these analyses allow us to understand the incentives that drive firms to intentionally structure deals to avoid antitrust scrutiny.

A. Existence of Stealth Acquisitions

We first examine whether firms seeking to avoid antitrust review structure financial contracts such that deal sizes bunch just below the pre-merger review dollar-based threshold, leading to a discontinuity in the number of M&As occurring in close proximity to the threshold. While circumventing the review process significantly reduces potential regulatory costs, such as forced asset divestitures or even blocking of the merger, to the benefit of shareholders, anticompetitive behavior following the acquisitions of existing or nascent competitors can attract complaints from customers and competitors in the aftermath of acquisitions. This in turn can prompt regulators to conduct post-acquisition reviews and issue enforcement actions aimed at deals that were not subject to pre-merger notification—even years after deals have been completed, which can be costly to shareholders. The significance of this threat is underscored by the fact that remedies sought by antitrust regulators in such cases can be harsher than in deals with pre-merger notification (Heltzer and Peterson (2018)). This is because the unwinding of transactions to restore competition to pre-merger levels can require the closure of business units, divesture of acquired assets at fire-sale prices, and other costly interventions.12 Such potential costs can disincentivize acquirers and targets from manipulating transaction sizes to avoid notification. Consistent with this view, Wollmann (2020) does not observe bunching of deal values just below the threshold in the dialysis industry. As such, the extent to which a discontinuity exists in the number of M&As surrounding the notification thresholds across sectors in the broader economy is an open question.

A.I. Research Design

To first document evidence on the existence of stealth acquisitions, that is, on a discontinuity in the number of M&A deals around the pre-merger notification threshold, we take advantage of two notable features of the HSR Act: (i) annual adjustments to the dollar-based threshold for requiring pre-merger notifications (shown in Figure 1), and (ii) the tracking of these adjustments to the U.S. gross national income growth rate. Together, these features result in a time-varying threshold that grows (or shrinks) by unequal dollar amounts annually, which we exploit to examine near-threshold deal size activity.

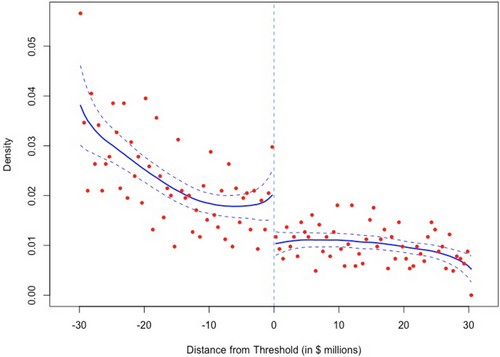

In our first set of tests, we use these signed distances and employ McCrary's (2008) test for a discontinuity at the threshold (e.g., Jäger, Schoefer, and Heining (2021)). The null hypothesis of the McCrary test in our setting is that the discontinuity around the pre-merger notification threshold is zero, that is, absent manipulation of deal sizes, a significant difference in the number of deals occurring just below relative to just above the threshold should be unobservable. In a first stage, McCrary's test obtains a finely graded histogram and smooths the histogram on either side of the threshold using local linear regression techniques. In a second stage, the McCrary test evaluates the difference in the density heights just below and just above the threshold. A finding of a significant difference in these heights would be indicative of a discontinuity.

A.2. Main Results

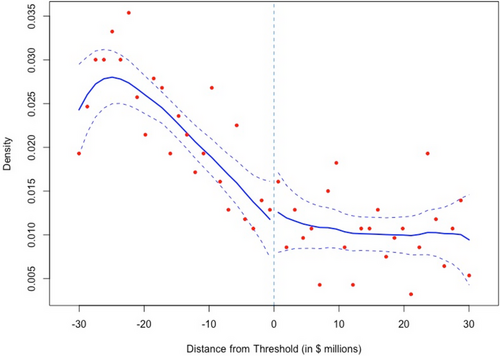

Figure 2 presents a graph of the McCrary (2008) test of continuity in the density function around the pre-merger review threshold. The solid lines, which depict the density function around the review threshold along with the 95% confidence intervals (i.e., dotted lines), provide visual evidence of a discontinuity. A Wald test, reported in Panel A of Table III, confirms this by rejecting the null of continuity of the density function at the threshold (p-value < 0.01).

| This table presents results of tests of the statistical difference between the frequency of just-below-threshold deals and just-above-threshold deals. In Panel A, we report results for the difference in density heights around the threshold related to Figures 2 and 5. The log difference in heights is from the perspective of the bin just to the right of the threshold (i.e., a negative sign indicates the right bin is lower than the left bin). In Panel B, we report results for the difference between actual and estimated frequencies of deals occurring in the bins just to the left and just to the right of zero related to Figure 3. *** indicates significance at the 1% level. The estimation procedure follows the methods in McCrary (2008) in Panel A and Burgstahler and Dichev (1997) in Panel B. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Difference in Density Heights | ||

| Log Diff. in Heights | t-Statistic | |

| Difference around threshold (Figure 2) | −0.680*** | −5.019 |

| Falsification test (Figure 4) | 0.129 | 0.445 |

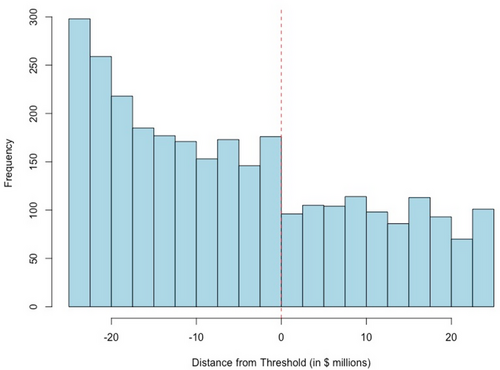

| Panel B: Difference in Estimated and Actual Bin Heights (Figure 3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bin | Frequency (Actual) | Frequency (Estimated) | Difference | t-Statistic |

| JustBelowThreshold | 176 | 121 | 55*** | 4.046 |

| JustAboveThreshold | 96 | 141 | −45*** | −3.103 |

The results above provide evidence that is consistent with the manipulation of deals by acquirers and targets to avoid pre-merger antitrust reviews. Nonetheless, we conduct several additional tests to further support this inference.14

In our initial additional test, given that the McCrary (2008) method automatically selects optimal bin widths, we construct a histogram on bin widths of $2.5 million around the pre-merger review threshold and compare the frequency of deals above versus below the threshold. The histogram, presented in Figure 3, shows that deal frequencies generally increase as deal values decrease. However, we find a sharp increase in the number of deals occurring in the bin to the immediate left of the threshold as compared to the bin to the immediate right.15 To test whether there is a significant difference in these bin heights relative to what we would expect, we employ a commonly used statistical approach for testing for discontinuities. This approach entails comparing the actual frequency of deals in each bin with the expected deal frequency, computed as the mean of deal frequencies in the two adjacent bins. The results, reported in Panel B of Table III, show that the actual number of deals in the left (right) bin is around 45% (30%) higher (lower) than the expected number (p-value < 0.01).16 Given that over our sample period the FTC and DOJ made 928 Second Requests, of which 10% involved mergers occurring above and within $50 million of the threshold, our results suggest an economically meaningful number of deals (i.e., 55) that represent a nearly 6% increase in Second Requests potentially manipulated to avoid pre-merger review.17,18

A.3. Falsification Tests

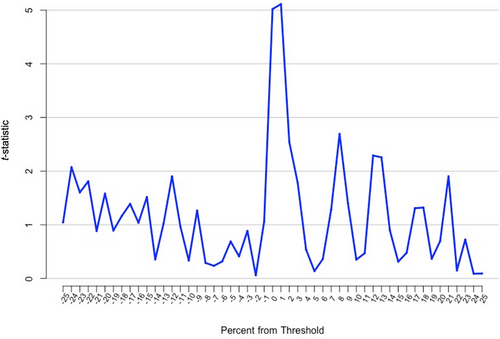

We conduct a set of falsification tests to help alleviate the concern that other prominent deal features explain the phenomenon we observe around the threshold. We first test for discontinuities at other points in the distribution of deals by constructing a set of “placebo” thresholds (e.g., Goncharov, Ioannidou, and Schmalz (2021)). To construct placebo thresholds, we adjust the actual threshold in a given year by ±1% to ±25% relative to the actual threshold value, and standardize the threshold each year around zero.19 Under the assumption that these other thresholds are as-if random, the rank of the McCrary t-statistic at the actual threshold when compared to the ranks of the McCrary t-statistics for these placebo thresholds indicates the probability of observing a similar t-statistic as we find in our main results by chance. We limit this analysis to 50 placebo thresholds—25 above the actual threshold and 25 below—since deals occur increasingly less (more) frequently above (below) the actual threshold, which could result in spurious discontinuities as there are significantly fewer deals (zero in many cases) in deal value bins far above the actual threshold.20 Using these 51 t-statistics, we estimate a p-value for the percentile rank, which is calculated by taking the rank of a t-statistic relative to the other t-statistics (rank) and dividing by the number of permutations (n) plus one (i.e., rank/n+1). The resulting p-value represents the probability of observing a discontinuity by random chance.

Figure 4 plots t-statistics over all 50 placebo thresholds and the actual threshold.21 The t-statistic for the discontinuity at the actual threshold—see Table III, Panel A—has the second-highest rank (i.e., rank = 2), with a p-value of 0.039 (2/51).22 To increase the precision of this test, we increase the number of permutations within ±1% to ±25% of the threshold to 100—50 above and 50 below the actual threshold—we randomly draw one threshold, and we repeat our analysis for all 100 permutations, resulting in 100 t-statistics. We find that the t-statistic for the actual threshold has the highest rank (rank = 1) and a p-value of 0.009 (i.e., 1/101).

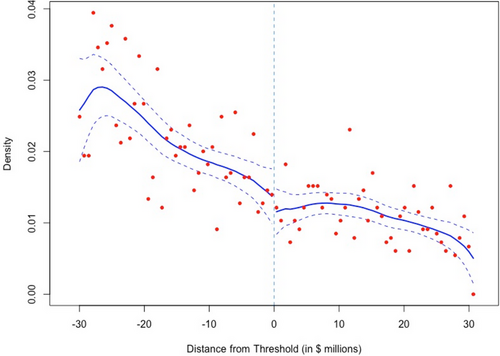

We conduct two additional falsification tests. First, we repeat our main McCrary test using a sample of real estate and hotel M&A deals that occur around the threshold and, by law, are always exempt from pre-merger review (FTC (2008)), and repeat the analysis in from our main McCrary test. The McCrary graph presented in Figure 5 reveals no detectable discontinuity around the threshold (t-statistic of 0.445; see also Table III, Panel A).23 Second, in Figure 6, we assign the following year's threshold to each year. We find no discontinuity under this alternative threshold. Collectively, the results from these falsification tests support our inference that the discontinuity of deals documented in our earlier analyses is driven by the manipulation of deals to avoid pre-merger reviews. In the following analysis, we examine the techniques and incentives that drive the avoidance of pre-merger antitrust review, and we explore the implications of these stealth acquisitions for acquirer and target shareholders, rivals, and consumers.

B. Financial Contracting for Stealth Acquisitions

We next examine whether deals bunching just below the threshold involve financial contract characteristics that differ systematically from (i) all other deals, and from (ii) deals just above the threshold in subsequent near-threshold tests.

We first focus on examining the types of acquirers and targets participating in just-below-threshold deals. We then examine a set of deal terms that legal practitioners suggest could incentivize or induce target managers to structure deals that avoid pre-merger reviews. Specifically, we look at (i) the form of payment (cash versus stock), (ii) the deal premium level, (iii) the use of contingency payments such as earnouts, (iv) the extension of D&O insurance for target managers and directors, and (v) the deductible acquirers are willing to pay before demanding breach-of-terms damages from the target.

B.I. Research Design

In our first set of tests, to provide evidence that JustBelowThresholdi,t deals differ in systematic ways from other deals occurring below but not proximate to the threshold, we estimate (2) using both our full sample of M&As and our sample of near-threshold deals.

B.2. Results

To determine the types of firms that are likely to be involved in stealth acquisitions, we estimate equation (2) using indicator variables that capture the ownership status of targets and acquirers (i.e., public versus private). Our results, reported in the first four columns of Table IV, indicate that deals that involve public acquirers buying public targets (column (1)) are less likely to fall just below the threshold. Notably, in column (2), we find that takeovers of privately held firms by publicly listed ones are 31.3% (0.005/0.016) more likely to be just-below-threshold deals, aligning with recent concerns of regulators on nonreportable deals undertaken by large public acquirers.25,26

| This table presents results from OLS regressions of M&As on acquirer-target characteristics. The dependent variable, JustBelow, is an indicator that assumes the value of 1 if a deal's transaction value is within a 10% window below the FTC annual pre-merger review threshold, and 0 otherwise. The main variables of interest in columns (1) to (4) are indicator variables that assume the value of 1 based on combined acquirer-target characteristics, and 0 otherwise. The main variables of interest in columns (5) to (8) are indicator variables that take the value of one if the deal's payment terms are structured as 100% cash, 100% stock, 100% cash and other (i.e., debt and earnouts), or 100% stock and other, respectively. We control for the size of the deal (DealValue) in all specifications and for public targets (PublicTarget) in columns (5) to (8). All variables are defined in Appendix A. All columns include target-firm industry fixed effects (using Fama-French 48-industry classifications) and year fixed effects. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses and calculated using standard errors clustered at the target-firm industry and year levels. *, **, *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| Public-Public | −0.007** | |||||||

| (−2.64) | ||||||||

| Public-Private | 0.005** | |||||||

| (2.71) | ||||||||

| Private-Private | −0.010*** | |||||||

| (−3.40) | ||||||||

| Private-Public | −0.004 | |||||||

| (−1.57) | ||||||||

| AllCash | 0.005* | |||||||

| (2.01) | ||||||||

| AllStock | −0.013*** | |||||||

| (−12.16) | ||||||||

| AllCashandOther | 0.008*** | |||||||

| (4.01) | ||||||||

| AllStockandOther | −0.006* | |||||||

| (−1.95) | ||||||||

| DealValue | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** | −0.000*** |

| (−3.82) | (−5.96) | (−5.08) | (−5.60) | (−4.22) | (−4.49) | (−3.47) | (−4.47) | |

| Constant | 0.019*** | 0.016*** | 0.020*** | 0.019*** | 0.018*** | 0.021*** | 0.013*** | 0.023*** |

| (231.01) | (17.09) | (238.40) | (362.25) | (51.04) | (132.57) | (11.17) | (16.50) | |

| Observations | 19,886 | 19,886 | 19,886 | 19,886 | 19,886 | 19,886 | 19,886 | 19,886 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Next, we evaluate the prevalence of cash-financed deals, which, by providing lower risk payoffs, might lead targets to accept a lower offer price that helps acquirers avoid pre-merger reviews. The results from this analysis, presented in columns (5) to (8) of Table IV, indicate that deals that include all-cash payments (column (4)) or a combination of cash and other nonstock consideration (column (7)) are indeed 28% (0.005/0.018) and 62% (0.008/0.013) more likely to be just-below-threshold deals. Conversely, we find that all-stock-financed acquisitions (column (6)) and deals employing a combination of stock and other noncash consideration (column (8)) are much less prevalent in just-below-threshold acquisitions.27 The greater use of cash versus stock payments in just-below-threshold deals is consistent with targets accepting the most liquid and least risky form of payments in exchange for a lower deal price, given post-acquisition holding requirements in stock transactions prescribed by U.S. securities laws (“Rule 144”; Latham and Watkins (2008)).28

In addition to, or as an alternative to, offering lower risk payoffs to targets, legal practitioners highlight other options available to acquirers that may facilitate the manipulation of deal values to avoid pre-merger notifications. First, we consider the use of earnouts, that is deferred payments that are contingent on a target's ability to meet or exceed certain milestones, in just-below-threshold deals. An important nuance of the pre-merger regulations is that the inclusion of contingency payments such as earnouts necessitates the assessment of the fair value of the acquisition rather than using the face value of the deal to determine whether the deal meets the size-of-transaction test for filing pre-merger notifications. The FTC expects that the fair value determinations will be performed in good faith and on a commercially reasonable basis by the acquirer's board of directors. However, use of an earnout could be an accounting and valuation method to generate a fair valuation that falls below the pre-merger notification thresholds.29 We investigate this possibility for a restricted sample of deals with values falling within a ±10% window centered around the FTC threshold after hand-collecting the relevant granular data on acquisitions—for example, use of extended D&O insurance—which would increase the power of these tests if collected for the full sample.30

Table V presents the results. Consistent with the view that earnouts allow greater discretion in assigning deal values, the results reported in column (1) indicate that the use of earnouts is associated with a 6.2-percentage-point increase (or 39% increase compared to the sample mean) in the probability of a deal being just below relative to just above the threshold (p-value < 0.05). When we examine whether earnouts account for a larger fraction of transaction value in the just-below-threshold deals, conditional on deals using earnouts, we do not find significant results (column (2) of Table V), likely due to the fact that the use of valuation methods to generate deal values below notification thresholds is triggered by the existence rather than the size of earnouts.

| This table presents results from OLS regressions of M&As on financial contract characteristics. The sample is restricted to observations for which the deal value falls within a ±10% window centered on the FTC threshold (see Table I, Panel B). The dependent variable, JustBelowThreshold, is an indicator variable that assumes the value of 1 if a deal's transaction value is within a 10% window below the FTC annual pre-merger review threshold, and 0 otherwise. The main variable of interest in column (1) is an indicator variable that assumes the value of 1 if the financial contract includes a provision for earnouts, and 0 otherwise. Results presented in column (2) are conditional on the inclusion of an earnout provision, where the main variable of interest is a continuous variable that measures the percentage of the transaction value represented by earnouts. All variables are defined in Appendix A. All columns include target-firm industry fixed effects (using Fama-French 48-industry classification) and year fixed effects. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses and calculated using standard errors clustered at the target-firm industry and year levels. **, *** indicate significance at the 5% and 1% level, respectively. The sample comprises 637 deals (base sample of 640 less three singletons). | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| Earnouts | 0.062** | |

| (2.42) | ||

| EarnoutPerc | 0.001 | |

| (0.66) | ||

| DealValue | −0.071*** | −0.108*** |

| (−11.01) | (−6.53) | |

| Constant | 5.022*** | 7.295*** |

| (12.60) | (7.25) | |

| Observations | 637 | 79 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.440 | 0.530 |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

Next, we examine the inclusion of financial contracting provisions by acquirers to lower deal prices below the pre-merger notification thresholds. In the context of our setting, for instance, the agreement to extend, and pay for, D&O coverage for private target firms can serve as another mechanism for acquirers to manipulate deal values to just below the threshold. Note that the cost to the acquirer of extending D&O coverage is not trivial, with combined premiums often exceeding $1 million, and is likely to be weighed against the total deal price (Goodwin Procter (2020)).31 To assess this possibility, we focus on private targets (which comprise the vast majority of firms involved in just-below-threshold deals), and hand-collect data on insurance payment terms for the deals in our sample.32 Table VI presents the results. In column (1), we find that extending D&O coverage for the former D&O of the target increases the likelihood of a deal being a stealth acquisition by 13.1 percentage points or 25% relative to the mean (p-value < 0.05).

| This table presents results from OLS regressions of M&As on financial contract terms. The dependent variable, JustBelowThreshold, is an indicator that assumes the value of 1 if a deal's transaction value is within a 10% window below the FTC annual pre-merger review threshold, and 0 otherwise. The main variable of interest in column (1), ExtendedLiabilityCoverage, is an indicator variable that assumes the value of 1 if the acquirer extends D&O coverage for the former directors and officers of the target, and 0 otherwise. The main variable of interest in column (2), DeductibleThreshold, is a continuous variable that measures the threshold (as a percentage of the total deal value) above which the target is responsible for post-acquisition claims against the acquirer. We also include controls for whether the representations and warranties survive beyond the effective date (RepsSurvive), the length of the survival period (SurvivalPeriod), and whether the holdback funds are held in escrow or otherwise (Escrow). All variables are defined in Appendix A. All columns include target-firm industry fixed effects (using Fama-French 48-industry classification) and year fixed effects. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses and calculated using standard errors clustered at the target-firm industry and year levels. **, *** indicate significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The sample comprises 122 deals in column (1) (base sample of 640 less 132 public targets less 366 deals with missing data to construct main independent variables less 12 deals with missing data to construct control variables less eight singletons). The sample comprises 99 deals in column (2) (base sample of 640 less 132 public targets less 379 deals for which terms do not survive beyond the closing date less 11 deals with missing data to construct main independent variable less nine deals with missing data to construct control variables less 10 singletons). | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| ExtendedLiabilityCoverage | 0.131** | |

| (2.16) | ||

| DeductibleThreshold | 18.705** | |

| (2.19) | ||

| DealValue | −0.108*** | −0.095*** |

| (−19.99) | (−14.36) | |

| Constant | 7.125*** | 6.020*** |

| (19.16) | (11.56) | |

| Observations | 122 | 99 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.603 | 0.609 |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

In column (2), we conduct another test that examines the level of the deductible that an acquirer is willing to accept before demanding post-acquisition breach-of-terms damages from the target. Deductible levels in a merger financial contract are analogous to deductibles in other settings (i.e., car or health insurance), in that a higher deductible should be associated with a lower deal premium. Thus, the existence of higher deductibles in just-below-threshold deals would be consistent with acquirers willing to accept higher post-closing risk in exchange for a lower deal price. Consistent with this view, we find that higher deductible thresholds are more likely for stealth acquisitions (p-value < 0.05). Taken together, the results from Table VI indicate that stealth acquisitions are more likely to feature financial contracting terms that implicitly compensate targets with greater legal protections that are typically associated with lower deal prices.

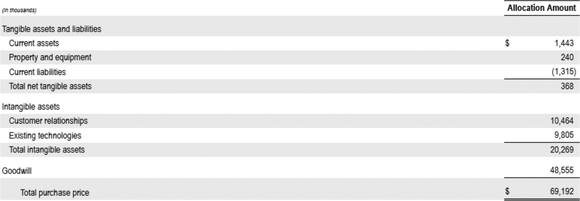

To the extent that firms employ financial contracting provisions to manipulate deal values to avoid antitrust review, we expect to find lower average deal premiums for targets just below versus just above threshold. However, an empirical challenge in assessing the deal values of private targets is that private firms do not have observable market values with which to calculate the premium paid by the acquirer firm. To overcome this limitation, we take advantage of SEC reporting rules that require publicly traded firms to report in their filings the amount paid for the target that is above the fair value of net assets (i.e., the goodwill portion of the deal). Because goodwill reflects the premium paid above the fair value of the target's net assets, it is analogous to the market premiums paid for public targets. We hand-collect from public SEC filings the reported goodwill amounts for all deals involving public acquirers and private targets around the threshold over our entire sample period and calculate the proportion of the deal value that is recognized as goodwill. Table VII presents the results. Column (1) indicates a negative relation between premiums paid for private targets and just-below-threshold deals (p-value < 0.10). This result suggests that an interquartile downward shift in deal premium increases the likelihood of a deal being below the threshold by 135%. In column (2), we find no difference between the deal premium paid for public targets in deals falling just above or just below the threshold.33 Taken together, this evidence is consistent with deal values, particularly for private targets, being manipulated to fall below the notification threshold.34

| This table presents results from OLS regressions of M&As on private-target deal premiums. The dependent variable, JustBelowThreshold, is an indicator that assumes the value of 1 if a deal's transaction value is within a 10% window below the FTC annual pre-merger review threshold, and 0 otherwise. The main variable of interest in column (1), PrivateTargetDealPrem, is a continuous variable that measures the premium paid for private targets. The main variable of interest in column (2), PublicTargetDealPrem, is a continuous variable that measures the premium acquirers pay for publicly traded target firms. All variables are defined in Appendix A. All columns include target-firm industry fixed effects (using Fama-French 48-industry classification) and year fixed effects. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses and calculated using standard errors clustered at the target-firm industry and year levels. *, **, *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. The sample comprises 219 deals in column (1) (base sample of 640 less 132 public targets less 102 deals with nonpublic acquirers less 184 deals with missing data to construct main independent variable less three singletons). The sample comprises 84 deals in column (2) (base sample of 640 less 508 private targets less 31 deals with missing data to construct main independent variable less 17 singletons). | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| PrivateTargetDealPrem | −0.199* | |

| (−1.96) | ||

| PublicTargetDealPrem | −0.000 | |

| (−0.25) | ||

| DealValue | −0.069*** | −0.060** |

| (−7.54) | (−2.80) | |

| Constant | 4.966*** | 4.030*** |

| (9.57) | (3.19) | |

| Observations | 219 | 84 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.449 | 0.373 |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

Finally, we consider corporate governance concerns such as the use of continued economic ties with target managers (e.g., Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny (1988), Fich, Cai, and Tran (2011)) and more attainable earnout targets as implicit compensation for lower deal values. We manually collect data on post-merger employment between target CEOs and the acquiring firms in near-threshold deals (e.g., from executives’ LinkedIn pages, Bloomberg, and public proxy statement profiles). To the extent that acquirers exploit such economic incentives to reduce the purchase price to below the pre-merger notification threshold, we expect a greater representation of deals with target CEOs retained by or offered an economic interest in an acquiring firm for deals that are just-below the threshold. Such private benefits can also persuade target CEOs to accept deal terms that contain contingency payments, since earnout negotiations are typically shaped by target executives who know how to maximize the probability of meeting the earnout targets. Accordingly, we examine whether economically connected executives are more likely to achieve post-acquisition earnout payoffs. Table VIII presents the results. In Panel A, we find a positive relation between target CEOs that have post-merger economic ties with acquirers and just-below-threshold deals (p-value < 0.05). Panel B documents a positive and significant (p-value < 0.01) interaction effect between CEOs with post-merger economic ties in acquirers and earnout payoffs in just-below-threshold deals. Together, these results are consistent with the use of discretion to employ target executives and with greater earnout payoffs as a means to implicitly compensate such executives for lower deal premiums.

| This table presents results from OLS regressions of M&As on acquirer-target CEO economic ties. The dependent variable, JustBelowThreshold, is an indicator that assumes the value of 1 if a deal's transaction value is within a 10% window below the FTC annual pre-merger review threshold, and 0 otherwise. In Panel A, the main variable of interest, EconomicTie, is an indicator that takes the value of one if the target CEO is retained by the acquiring firm and/or has an economic interest in the surviving firm. We also control for whether the acquirer is public (PublicAcquirer) and for whether the merger is horizontal (Horizontal). In Panel B, column (1), the main variable of interest is EarnoutPayoff, and in column (2) the main variable of interest in the interaction term EconomicTie × EarnoutPayoff. All variables are defined in Appendix A. We include target-firm industry fixed effects (using Fama-French 48-industry classification) and year fixed effects. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses and calculated using standard errors clustered at the target-firm industry and year levels. **, *** indicate significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The sample comprises 423 deals in Panel A (base sample of 640 less 208 deals with missing data on economic ties less nine singletons). The sample comprises 39 (29) deals in column (1) ((2)) of Panel B (base sample of 640 less 551 deals without earnouts less 44 deals with missing data on earnout payoffs less six singletons). | |

|---|---|

| Panel A: Economic Ties and Below-Threshold M&As | |

| (1) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow |

| EconomicTie | 0.084** |

| (2.15) | |

| DealValue | −0.078*** |

| (−8.67) | |

| Constant | 5.341*** |

| (9.66) | |

| Observations | 423 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.466 |

| Controls | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes |

| Panel B: Economic Ties and Earnout Payoffs | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| EarnoutPayoff | 0.059 | −0.386 |

| (0.49) | (−1.78) | |

| EconomicTie | −0.198 | |

| (−1.31) | ||

| EconomicTie × EarnoutPayoff | 0.590*** | |

| (9.04) | ||

| DealValue | −0.144*** | −0.151*** |

| (−10.12) | (−6.06) | |

| Constant | 9.190*** | 9.682*** |

| (12.11) | (6.84) | |

| Observations | 39 | 29 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.753 | 0.505 |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

C. Heterogeneity in Stealth Acquisitions: Incentives to Coordinate

We next examine whether horizontal M&As (i.e., targets and acquirers operating in the same industry), deals between geographically proximate targets and acquirers, and deals in concentrated industries—all of which represent M&As that are theoretically more likely to lead to anticompetitive outcomes—have a higher likelihood of falling just below the threshold.

C.1. Research Design

| This table presents results from OLS regressions of M&As on acquirer-target industry and location characteristics. The sample is restricted to observations for which the deal value falls within a ±10% window centered around the FTC threshold. In Panels A and B, the dependent variable, JustBelowThreshold, is an indicator variable that assumes the value of 1 if a deal's transaction value is within the 10% window below the FTC annual pre-merger review threshold, and 0 otherwise. In Panel A, the main variables of interest in columns (1) and (2) are indicator variables that assume the value of one based on whether the target and acquirer share the same four-digit SIC code (i.e., horizontal merger) or share the same state of operations (i.e., intrastate). In column (3), the main variable of interest is the interaction term, Horizontal × Intrastate, which takes the value of 1 if the merger is both horizontal and intrastate, and 0 otherwise. All variables are defined in Appendix A. In Panel B, columns (1) and (4), the main variable of interest, HighConc, is an indicator that assumes the value of 1 if the target firm's industry is above the median concentration, and 0 otherwise. In columns (2) and (5) and (3) and (6), the main variables of interest are interaction terms Horizontal × HighConc and Intrastate × HighConc, which assume the value of 1 when the target firm's industry is above the median concentration and the acquirer and target share the same four-digit SIC code (in columns (2) and (5)), or share the same state of operations (in columns (3) and (6)), and 0 otherwise. In columns (1) to (3) industry concentration is estimated using the methodology in Hoberg and Phillips (2010b) (Conc_HP). In columns (4) to (6), industry concentration is estimated using net sales by four-digit SIC code, by year (Conc_Sales) (Hou and Robinson (2006)). All variables are defined in Appendix A. All columns in Panel A include target-firm industry fixed effects (using Fama-French 48-industry classifications) and year fixed effects, while all columns in Panel B include industry fixed effects. Robust t-statistics are reported in parentheses and calculated using standard errors clustered at the target-firm industry and year levels. *, **, *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. The sample comprises of 637 deals in Panel A (base sample of 640 less three singletons). The sample comprises 501 in columns (4) to (6) in Panel B (base sample of 640 less 136 deals with missing data to construct HHI measure less three singletons). | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Horizontal and Intrastate M&As | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| Horizontal | 0.066** | 0.028 | |

| (2.61) | (1.43) | ||

| Intrastate | −0.061 | −1.26* | |

| (−1.31) | (−1.92) | ||

| Horizontal × Intrastate | 0.194*** | ||

| (2.91) | |||

| DealValue | −0.072*** | −0.072*** | −0.072*** |

| (−10.81) | (−11.06) | (−11.45) | |

| Constant | 5.048*** | 5.064*** | 5.076*** |

| (12.35) | (12.66) | (13.17) | |

| Observations | 637 | 637 | 637 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.442 | 0.440 | 0.447 |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Panel B. Highly Concentrated Industry M&As | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Dependent Variable | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow | JustBelow |

| Measure of HighConc | Conc_HP | Conc_HP | Conc_HP | Conc_Sales | Conc_Sales | Conc_Sales |

| HighConc | −0.003 | −0.024 | −0.009 | 0.011 | −0.014 | 0.050 |

| (−0.12) | (−1.15) | (−0.36) | (0.28) | (−0.27) | (1.30) | |

| Horizontal | 0.005 | 0.013 | ||||

| (0.25) | (0.55) | |||||

| Horizontal x HighConc | 0.100** | 0.133** | ||||

| (2.24) | (2.27) | |||||

| Intrastate | −0.105* | 0.036 | ||||

| (−1.80) | (0.45) | |||||

| Intrastate x HighConc | 0.051 | −0.223 | ||||

| (0.60) | (−1.62) | |||||

| DealValue | −0.071*** | −0.072*** | −0.072*** | −0.074*** | −0.074*** | −0.075*** |

| (−11.11) | (−11.32) | (−11.47) | (−10.45) | (−10.64) | (−11.59) | |

| Constant | 5.035*** | 5.055*** | 5.069*** | 5.111*** | 5.110*** | 5.173*** |

| (12.53) | (12.76) | (13.01) | (11.86) | (12.18) | (12.96) | |

| Observations | 640 | 640 | 640 | 501 | 501 | 501 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.444 | 0.447 | 0.446 | 0.460 | 0.464 | 0.467 |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | No | No | No | No | No | No |

C.2. Results

Prior to estimating equation (3), we again employ McCrary's (2008) test to examine the discontinuity around the threshold after restricting attention to horizontal mergers. Figure IA.4 in the Internet Appendix shows this result. We find a noticeable jump in the number of horizontal deals just to the left of the threshold, which we verify with a Wald test (p-value < 0.01). It is important to note that while prior research suggests that changing the notification threshold level is associated with more horizontal mergers at all deal-size levels below the threshold (Wollmann (2019)), our findings in this section reveal a higher-than-expected number of such mergers in deals that are just below the threshold.

Next, we estimate equation (3) for the sample of deals that fall immediately below and above the pre-merger notification threshold. The results, reported in column (1) of Table IX, Panel A, confirm a greater likelihood horizontal mergers occurring just below the threshold (p-value < 0.05). Notably, we do not find that deals in which targets and acquirers share the same state of operations, which can allow acquirers to realize significant gains than from geographic proximity are more likely to fall just below threshold (column (2) of Panel A). However, when we expand the analysis to include interaction effects of these intrastate deals and horizontal mergers in column (3) of Panel A, we find a significant result for the interaction effect, indicating that our findings for horizontal mergers in column (1) are driven by intrastate horizontal mergers (p-value < 0.01).