Facial psoriasis in the etiology of prolonged erythema following medium-depth chemical peels for severe photodamage

Abstract

Background

Chemical peeling is the controlled wounding of the epidermis and dermis for skin rejuvenation, involving the application of ablative agents to induce keratolysis and regeneration of damaged cell layers. Prolonged erythema is one complication of this procedure. We report the prevalence and probable etiology of prolonged facial erythema in a cohort of patients treated with medium-depth chemical peels.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective audit was conducted of all medium-depth facial chemical peels performed at two major teaching hospitals. All patients had severe facial photodamage affecting at least 75% surface area of the face. The occurrence of prolonged erythema following this peel was then identified and analyzed.

Results

Of our treatment cohort (n = 82, 51 women, 31 men) with 60 years mean (61.3 years for women, 56.7 years for men), 10 patients (12%; eight women, two men) experienced prolonged erythema beyond a month of treatment. Facial psoriasis was not apparent at the time of chemical peel but manifested as prolonged erythema beyond the expected timeframe following the procedure.

Conclusion

When patients experience prolonged erythema beyond a month of treatment and fail to respond to standard treatments, clinicians should examine carefully for extra-facial psoriasis prior to this procedure, and also consider facial psoriasis a possible cause of prolonged post-peel erythema.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chemical peeling is the controlled wounding of the epidermis and dermis for medical and aesthetic rejuvenation.1 Chemical peels involve the application of one or more chemical ablative agents to the skin to induce keratolysis or keratocoagulation.2 Consequently, regeneration and remodeling of these cutaneous layers occur, resulting in regeneration of damaged cell layers.3

Chemical peels are classified according to depth of penetration of the skin; as superficial, medium, or deep. The depth of penetration is determined by the type, concentration, and pH of the peeling agent and the application technique.4 Anatomical location, epidermal integrity, adnexal structure density, and skin thickness also influence the depth of peel achieved.4

Complications of this procedure include dyspigmentation, scarring, infection, milia, acneiform eruptions, allergic reactions, and cardiotoxicity.1 Concomitant inflammatory dermatoses may worsen with chemical peeling, including eczema, psoriasis, vitiligo, rosacea, and seborrheic dermatitis.3, 5 Furthermore, these dermatoses may increase the risk of disease exacerbation as well as postoperative complications, such as excessive and/or prolonged erythema, hypersensitivity, or impaired healing.5

Prolonged erythema has been reported to occur in 11% of deep chemical peel patients.6 Among these patients, it has thus far been attributed to angiogenic factors stimulating vasodilatation and it has been considered an indicator of prolonged stimulation of fibroplasia.7 When the duration of erythema exceeds 3 weeks and is associated with pruritus, this may indicate hypertrophic scarring and should be treated with standard approaches for this procedural complication, such as pulsed dye laser or topical/intralesional/systemic corticosteroid.8

To date, such prolonged erythema has been thought to be due to pre-/post-treatment retinoid use, exacerbation of pre-existing skin disease, genetic susceptibility, contact dermatitis, contact sensitization, and consumption of alcohol.9

The use of cosmetics, sunscreen, emollient, or topical corticosteroids postoperatively may also result in prolonged erythema. Some experts believe that in cases of prolonged erythema with textural change, a true corticosteroid allergy should be excluded.6

Psoriasis is a chronic, multisystem, inflammatory disease predominantly affecting the skin and joints.10 Approximately 30% of patients with psoriasis have a positive family history,11 and prevalence of psoriasis has been quoted as low as 0.27% and as high as 11.4%.12 Psoriatic plaques are characterized by dysfunctional keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.13 Histologically, acanthosis and epidermal hyperplasia overlie an inflammatory infiltrate, while dermal papillae contain dilated, tortuous blood vessels.14 Currently, the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) is the most widely adopted clinical measure for the condition, based on area of involvement and the degree of erythema, induration, and desquamation.15

Facial involvement is a marker for severe psoriasis, and is associated with longer disease duration, earlier onset, extracutaneous involvement, and the need for more extensive treatment.16, 17 Facial involvement occurs in approximately 29.9% of psoriasis patients.18

We report the prevalence of prolonged facial erythema in a cohort of 82 patients treated with medium-depth chemical peels (hereafter referred to as peel/s), in whom an etiology of facial psoriasis was uncovered.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective audit was conducted of all full-face peels performed at two major teaching hospitals in New South Wales, Australia, between January 2018 and August 2022. All patients had severe facial photodamage affecting at least 75% surface area of the face. Figure 5C, a clinical image taken immediately pre-peel, is representative of the degree of qualifying sun damage in our treatment cohort.

Treatment consisted of skin preparation with 70% isopropyl alcohol followed by Jessner's solution and 50% trichloroacetic acid (by light dabbing only using unwoven gauze), to the point of a uniform medium white frost. No keratolytic pre-treatment was prescribed, and all patients included had severe photodamage that affected at least 75% facial surface. None of these patients had moderate or severe extra-facial psoriasis, or any degree of facial psoriasis, at the time of the peel. The occurrence of post-peel prolonged facial erythema was then identified, regardless of any evidence of concomitant psoriasis at the time.

3 RESULTS

Of our treatment cohort (n = 82, 51 women, 31 men) with 60 years mean (61.3 years for women, 56.7 years for men), 36 patients (44%; 21 female, 15 men) had mild extra-facial psoriasis prior to the peel. In all, 10 patients (12%; eight women, two men) experienced prolonged erythema beyond a month of treatment. All 10 patients had mild extra-facial psoriasis prior to their peel. Facial psoriasis was not apparent at the time of peel but manifested as prolonged erythema beyond the expected timeframe for resolution following the procedure.

Standard therapies for facial psoriasis were employed, resulting in resolution of facial erythema among all patients who agreed to adhere to a conventional treatment ladder of standard topical and/or oral therapies appropriate for the degree of psoriasis exhibited; including progressing to biologic therapy where indicated.

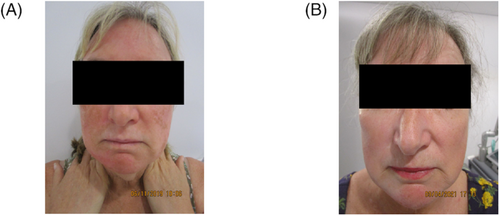

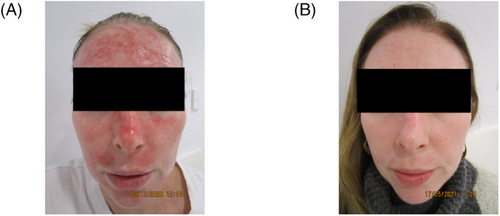

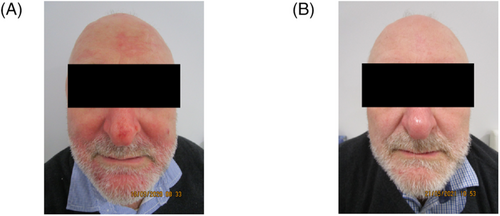

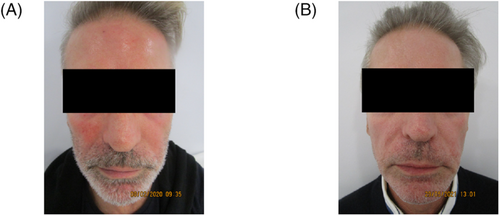

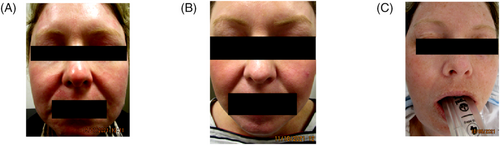

Details and management summaries of patients affected by such prolonged erythema are presented in Table 1, while Figures 1-5 demonstrate the facial appearance of patients 3, 5, 6, 7, and 10, in order, pre- (a) and post-treatment (b) of facial psoriasis.

| P | Age (years), sex | Pre-existing dermatologic conditions | Prominent facial erythema durationa | Facial PsO diagnosis | Non-facial involvement of PsO | Treatment for erythema before facial PsO dx | Treatment for facial PsO | Response to treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65, F | None | February 11, 2020–September 30, 2020 | June 17, 2020 | Morning stiffness of hands/shoulders/knees consistent with PsA |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema; improvement of energy levels and arthralgia |

| 2 | 47, F | Varicose veins and androgenic alopecia | December 23, 2019–ongoing | February 19, 2020 | Bilateral knee morning stiffness |

|

|

Improvement of arthralgia; declined follow-up |

| 3 | 60, F | Varicose veins, dilated pore of Winer, and seborrheic keratosis | August 23, 2019–December 19, 2020 | June 26, 2020 | Left inframammary chest, left inguinal crease, and nails |

|

|

Modest improvement in facial erythema and extra-facial psoriasis with risankizumab; resolution of facial erythema and clearance of extra-facial psoriasis following change of agent to ixekizumab |

| 4 | 55, F | Staphylococcal impetigo, suture granuloma, melasma, pityriasis versicolor, and notalgia paresthetica | September 10, 2020–ongoing | October 21, 2020 | Nails |

|

|

Declined follow-up |

| 5 | 44, F | Basal cell carcinoma and varicose veins | August 20, 2020–February 6, 2021 | October 14, 2020 | Palmoplantar, elbows and nails |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema; clearance of extra-facial psoriasis |

| 6 | 60, M | Varicose veins | August 20, 2020–April 9, 2021 | November 4, 2020 | Palmoplantar and fingernails; morning stiffness of axial and peripheral joints |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema and arthralgia |

| 7 | 60, M | None | December 24, 2019–May 8, 2021 | December 5, 2020 | Nails and right leg |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema; clearance of extra-facial psoriasis |

| 8 | 80, F | Squamous cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, solar keratosis, tinea corporis, and myxoid cysts | December 24, 2019–September 6, 2020 | July 29, 2020 | Morning stiffness of left third distal interphalangeal joint psoriasis |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema |

| 9 | 83, F | Varicose veins, seborrheic keratosis, solar keratosis, keratoacanthoma, tinea corporis, and Grover's disease | June 5, 2019–January 20, 2020 | August 23, 2019 | Scalp and nails |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema; improvement of extra-facial psoriasis |

| 10 | 42, F | Melasma and arthropod bite reaction | May 18, 2021–October 11, 2021 | June 15, 2021 | Soles and nails |

|

|

Resolution of facial erythema; clearance of extra-facial psoriasis |

- Abbreviations: dx, diagnosis; F, female; M, male; MTX, methotrexate; P, patient; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis; UVA, ultraviolet A; UVB, ultraviolet B; ×/week, times per week.

- a From date of chemical peel.

4 DISCUSSION

Peels have been used for centuries to improve the signs of photodamage.1 Ultraviolet radiation, through reactive oxygen species, incurs damage to DNA molecules, fatty acids, carbohydrates, and proteins, including collagen and elastin.19 The structural framework of cutaneous fibers is severely affected by photodamage, and its degeneration leads to a gradual loss of tissue support with cosmetic ramifications.19, 20

We propose that the clinical signs of facial psoriasis, such as erythema and scale, may be masked by cutaneous changes resulting from ultraviolet radiation. Therefore, the exfoliative effects of peels may uncover underlying facial psoriasis following the shedding of a photodamaged skin layer.

The masking of erythema is explained by the Tyndall effect, which describes how shorter wavelengths (e.g., blue) are dispersed and reflected more than longer wavelengths (e.g., red).21 When visible light enters a non-homogenous medium, longer wavelengths continue through the medium with less scatter. Therefore, observers do not detect red-orange colors as well.22 In patients with skin thickening resulting from severe photodamage, erythema appears more flesh-colored due to reduced scatter, in effect masking erythema. While several devices are currently available for specific quantification of skin erythema,23 we recorded facial erythema visually by standard digital photography, which is most readily available to practitioners.

Scale may be masked by a similar increase in skin density and induration due to elastin production being disrupted by ultraviolet radiation, leading to inadequate protein synthesis required for proper assembly of elastic fibers. Hence, loss of cutaneous elasticity is a direct reflection of ultraviolet radiation damage and alterations in elastic fiber production.19

The epidermis thickens in response to ultraviolet radiation reaching the proliferative basal layer.24 Typically, photoaged skin exhibits solar elastosis, an accumulation of dystrophic elastotic material in the dermis,19 in association with altered collagen fibers.25 This may play a role in increasing thickness and induration, which may be difficult to differentiate from the induration of facial psoriasis.

Cutaneous exposure to ultraviolet radiation can result in changes to intracellular components of the stratum corneum, such as intercellular lipids and corneodesmosomes. These alterations to the mechanical barrier function of the superficial epidermis can lead to severe macroscopic skin damage, including associated inflammation, abnormal desquamation, chapping, and fissuring.25

Corneodesmosomes are critical to desquamation, an essential protective mechanism by which there is complete stratum corneum turnover in 2–4 weeks.26 Corneodesmosome damage by ultraviolet exposure may alter normal desquamation, potentially leading to longer-term barrier disruption.25 Therefore, similar to the masking of psoriatic induration, the desquamation (otherwise described as scale) of psoriasis may also be masked.

Facial psoriasis arising de novo is an alternate mechanism for its occurrence among peel patients, particularly since this may be explained by the Koebner phenomenon in patients with psoriasis, but without any pre-existing facial involvement. On closer scrutiny of clinical history and examination retrospectively, each patient affected by prolonged erythema had evidence of mild extra-facial psoriasis at the time of peel. In contrast, 64% of patients who did not develop prolonged erythema had no evidence of pre-existing mild extra-facial psoriasis.

Our data suggest that facial psoriasis is the probable cause of prolonged erythema in the context of peels. Resolution of prolonged erythema was only achieved for each patient by adhering to a conventional treatment ladder for psoriasis. Interestingly, compared with reported prevalence of prolonged erythema in deep peel patients (11%),6 the prevalence among our patients, in whom this was attributed to facial psoriasis, is strikingly similar (12%).

When patients fail to respond to standard treatments for prolonged erythema, such as topical/intralesional/systemic corticosteroids, topical/systemic antibiotics, emollients, and sunscreen, clinicians should consider the possibility of facial psoriasis preventing expected recovery. It is therefore crucial to examine carefully for even minor signs of extra-facial cutaneous and non-cutaneous psoriasis, including involvement of the palms, soles, genitals, nails, and skin flexures; which may have been inadvertently missed at pre-treatment clinical assessment.

The possible masking of facial psoriasis by severe photodamage poses two potential clinical dilemmas. First, unexpected sequelae may follow a peel as a result of pre-existing inflammatory dermatoses. Second, this raises the index of suspicion for severe psoriasis in a segment of patients considered suitable candidates for peel; and more diligent pre-treatment clinical assessment and history-taking for psoriasis may be justified. Of note, patients 1 and 5 are maternal aunt and niece, respectively, suggestive of familial psoriasis.

5 CONCLUSION

We present the first case series proposing a probable etiology (with two alternate mechanisms) for prolonged erythema, a distressing yet not uncommon complication of both deep and medium chemical peels. Our report emphasizes the importance of careful patient selection and focused clinical assessment, and relevant management, for extra-facial as well as facial psoriasis prior to this common dermatologic procedure. Further, considering psoriasis in the work-up, preparation and aftercare of peel patients must be standard practice.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Liang Joo Leow and Mr Nicolas Zubrzycki contributed significantly to this manuscript to justify authorship criteria. Dr Liang Joo Leow conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Mr Nicolas Zubrzycki and Dr Liang Joo Leow edited, read, and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None declared.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.