Tranexamic acid microinjections versus tranexamic acid mesoneedling in the treatment of facial melasma: A randomized assessor-blind split-face controlled trial

Abstract

Background

Melasma is a hyperpigmentary disorder causing cosmetic disfigurement. We aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid (TXA) microinjections with TXA mesoneedling for facial melasma.

Methods

This randomized assessor-blind split-face controlled trial included patients with symmetric facial melasma. One side of the face received TXA (100 mg/ml) mesoneedling and the other side intradermal TXA microinjections. The interventions were repeated three times with 4-week intervals (weeks 0, 4, and 8). The primary outcome was improvement in modified Melasma Area and Severity Index (mMASI) 4 weeks after the final treatment session. Secondary outcomes were complications and patient satisfaction with the treatments evaluated by a visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

All 27 patients included in the study were female (mean age: 44.22 ± 8.39 years). Both groups were comparable in terms of mMASI scores before and after treatment (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.22; 0.85, p = 0.248 and SMD = −0.13, 95% CI −0.66; 0.40, p = 0.633, respectively). The mMASI score change from baseline was not different (SMD = −0.39, 95% CI −0.93; 0.15, p = 0.157). However, patient satisfaction was significantly higher with TXA mesoneedling (SMD = 0.77, 95% CI 0.21; 1.32, p = 0.007). Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurred in one patient in the TXA mesoneedling group. Erythema, scaling, and edema were significantly higher with TXA mesoneedling (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

TXA mesoneedling was comparable with TXA microinjection in the treatment of facial melasma, while patient satisfaction was significantly higher with TXA mesoneedling; however, the high frequency of complications occurring with this treatment should be taken into account.

1 INTRODUCTION

Melasma is an acquired hyperpigmentary disorder emerging most commonly as symmetric patches and macules on the areas of face and neck exposed to sun.1 In fact, melasma is considered a cosmetic disfigurement that can adversely influence the quality of life.2 Melasma can differ in severity as there are differences in the intensity of pigmentation and area of involvement. The patients' appearance can be more affected in severe cases, causing them to seek treatment.3 Although pregnancy, exposure to ultraviolet, genetic predisposition, inflammatory conditions, phototoxic drugs, contraceptive pills, and sex hormones have been associated with melasma, the exact underlying mechanism is not completely understood.4

Several treatments exist for melasma, such as depigmenting agents, chemical peeling, and laser ablation; however, none is universally accepted in terms of efficacy and patient satisfaction.4 Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a plasminogen activation inhibitor and a synthetic lysine analog, primarily used as an antifibrinolytic or antihemorrhagic agent.5 It has also been used for the treatment of melasma. Evidence shows that TXA contributes to the reduction in epidermal melanin content, mast cell numbers, and dermal vascularity6; nevertheless, its precise mechanism of action remains unknown. TXA has been applied through different modes of administration, including topically, orally, and intradermally, in the treatment of melasma.7-9 Since the uptake of TXA, when used topically, may not be high enough, different strategies have been applied to increase the delivery of TXA to the target tissue.10

Microneedling uses fine needles to cross the skin barrier and deliver the drug directly to the dermis, resulting in increased penetration of the drug.11 This method has been effective for the treatment of melasma either alone or in combination with TXA.12, 13 Microinjections of TXA have also been used for melasma, showing promising results.14 In the current study, we aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of TXA microinjections to topical TXA with microneedling in the treatment of facial melasma.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants and study design

First, the general characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, and Fitzpatrick skin type were recorded. Then, they were randomized into two groups (A and B), using block randomization by the Random Allocation software. Twenty-seven unclear envelopes were prepared by the statistician in charge of randomization. A card was placed in each envelope with one side indicating the group (A/B) and the other side indicating the side of the face to receive each treatment. The envelopes were then sealed. An envelope was selected by each patient after having them shuffled. Patients in group A (n = 13) received TXA with microneedling (mesoneedling) on the right and intradermal TXA microinjections on the left side of their face, while those in group B (n = 14) received microinjections on the right and mesoneedling on the left side.

Before the procedures, all patients received sufficient amounts of Xyla-p cream (Tehram Chemie Pharmaceutical Co.) on both sides of their face (as a local anesthetic), which was rinsed after 30 min and then sterilized by alcohol. Afterward, for the side of the face receiving microneedling, TXA solution (500 mg/5 ml ampule, Caspian Pharmaceutical Co., Iran) was spread uniformly to all areas, immediately followed by microneedling (needle depth 1.5–2 mm with sweeping movements in every direction (like an asterisk “*”, horizontally, vertically, and diagonally), InnoPen™ device), two passes in each direction. Of note, TXA was repeatedly applied between each sweeping movement and after microneedling. For the side of the face receiving microinjections, the same TXA solution (0.1 ml) was injected at 1 cm intervals using a 0.5 ml insulin syringe with a 30-gauge needle. The face was rinsed by sterile irrigation solution after interventions. Patients with a history of herpes infection received antiviral prophylaxis (valacyclovir 500 mg twice a day) on the day of the procedure, which continued for 5 days. All patients had applied hydroquinone 4% cream (Sobhan Daru Co.) bilaterally on their cheeks every night for a month before receiving the interventions and also during the study as the principal treatment; however, they would stop its application 48 h before and until 48–72 h after each treatment session. In addition, all participants started using sunscreens with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 30 1 month before the study and during the study. Overall, the interventions were repeated 3 times with 4-week intervals (weeks 0, 4, and 8). The primary outcome was improvement in modified Melasma Area and Severity Index (mMASI) determined by an assessor blinded to the received interventions, both at baseline and 4 weeks after the final treatment session (evaluated by the same assessor). In this index, the right and left malar areas are scored in terms of area of involvement (A) ranging from 0 to 6, with “0” indicating no involvement; “1,” <10%,”2,″ 10%–29%, “3,″ 30%–49%, “4,″ 50%–69%, “5,″ 70%–89%, and “6,″ 90%–100% involvement and darkness (D) ranging from 0 to 4, with “0″ indicating normal skin color; “1″ barely visible hyperpigmentation; “2,″ mild; “3,″ moderate; and “4,″ severe hyperpigmentation.15 The scores were then put into the following formula to calculate mMASI total score: 0.3 × A × D (right malar) + 0.3 × A × D (left malar). Moreover, the patients were photographed using the Canon SX10 IS digital camera under standardized lighting (in the same room and position, with the same light, and at a similar distance) before and 4 weeks after treatments.

Secondary outcomes were complications, including erythema, edema, scaling, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), as well as patient satisfaction with the treatments on each side of the face, evaluated by a visual analog scale (VAS) 4 weeks after the final treatment session (0–10, with “0” indicating no satisfaction and “10” indicating complete satisfaction with the treatments).

2.2 Data analysis

We used mean and standard deviation to describe continuous variables and frequency and percentage to describe categorical variables. The distribution normality of the continuous variables was determined by means of histograms, skewness and kurtosis indices, and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Accordingly, the independent t-test was used to compare continuous variables between groups. The effect size used for comparison was standardized mean difference (SMD) by Cohen's d method. SMD was interpreted based on the following: 0–0.19, trivial; 0.20–0.49, small effect; 0.50–0.79, medium effect; and ≥0.80, large effect.16 The Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical data between groups and risk ratios were reported as effect size with the following interpretations: 0–0.81, trivial effect; 0.53–0.82, small effect; 0.32–0.54, medium effect; and ≤0.33, large effect.17 All data were analyzed using the Stata software (version 14.2). p-Values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

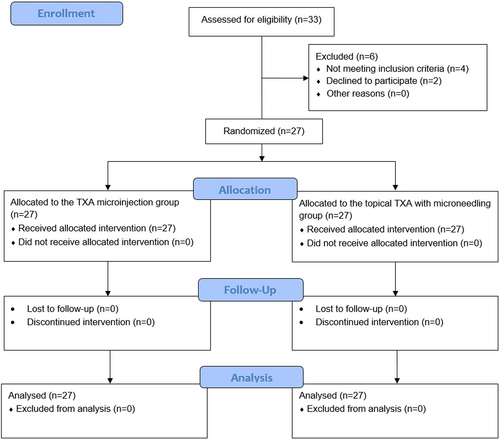

Initially, 33 patients were evaluated for eligibility, of whom two declined to participate and four did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). General characteristics of the remaining 27 patients are presented in Table 1. All patients were female, with a mean age of 44.22 ± 8.39 years. Most of the patients had Fitzpatrick skin type III (66.7%).

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (years) mean (SD) | 21 (52.5) |

| Sex N (%) | |

| Male | 0 (0.0) |

| Female | 27 (100.0) |

| Fitzpatrick skin type N (%) | |

| II | 2 (7.4) |

| III | 18 (66.7) |

| IV | 6 (22.2) |

| V | 1 (3.7) |

- Abbreviations: N, number; SD, standard deviation.

Both groups were comparable in terms of mMASI scores before and after treatment (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.22; 0.85, p = 0.248 and SMD = −0.13, 95% CI −0.66; 0.40, p = 0.633, respectively). Also, the change in mMASI scores from baseline was not different between groups (SMD = −0.39, 95% CI −0.93; 0.15, p = 0.157) (Table 2). However, patient satisfaction was significantly higher with TXA mesoneedling compared to TXA microinjection (SMD = 0.77, 95% CI 0.21; 1.32, p = 0.007) (Table 3). Photographs of a patient before and after treatment are illustrated in Figure 2.

| mMASI | TXA mesoneedling (n = 27) | TXA microinjection (n = 27) | p-Valuea | ES (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment, mean (SD) | 2.36 (0.80) | 2.09 (0.89) | 0.248 | 0.32 (−0.22; 0.85) |

| After treatment, mean (SD) | 1.08 (0.87) | 1.19 (0.83) | 0.633 | −0.13 (−0.66; 0.40) |

| Change, mean (SD) | −1.28 (0.99) | −0.89 (0.96) | 0.157 | −0.39 (−0.93; 0.15) |

- Note: ES indicates standardized mean difference (SMD) by Cohen's d.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; mMASI, modified Melasma and Area Severity Index; SD, standard deviation; TXA, tranexamic acid.

- a Analyzed by the independent t-test.

| Satisfaction | TXA mesoneedling (n = 27) | TXA microinjection (n = 27) | p-Valuea | ES (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS, mean (SD) | 8.85 (0.95) | 8.00 (1.24) | 0.007 | 0.77 (0.21; 1.32) |

- Note: ES indicates standardized mean difference (SMD) by Cohen's d.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; SD, standard deviation; TXA, tranexamic acid; VAS, visual analog scale.

- a Analyzed by the independent t-test.

As for complications, PIH only occurred in 1 patient of the TXA mesoneedling group. All other complications, including erythema, scaling, and edema were significantly more frequent with TXA mesoneedling compared to TXA microinjection (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Complications, N (%) | TXA mesoneedling (n = 27) | TXA microinjection (n = 27) | p-Valuea | ES (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema | 23 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.06; 0.44) |

| Scaling | 25 (92.6) | 2 (7.4) | <0.001 | 0.08 (0.02; 0.30) |

| Edema | 19 (70.4) | 4 (14.8) | <0.001 | 0.21 (0.08; 0.51) |

| PIH | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000b | - |

- Note: ES indicates risk ratio.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; N, number; PIH, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation; TXA, tranexamic acid.

- a Analyzed by the chi-squared test.

- b Analyzed by Fisher's exact test.

4 DISCUSSION

In the current study, we found comparable improvement in mMASI scores with both TXA mesoneedling and TXA microinjections for the treatment of facial melasma. On the other hand, patient satisfaction was significantly better (medium effect) with TXA mesoneedling, while complications were more frequent with this therapeutic modality. We used a TXA concentration of 100 mg/ml and did not dilute TXA or mix it with anything else. Hadid et al.18 also used intradermal TXA with this concentration in one arm of their study, yet reported similar results with different TXA concentrations. The goal of microneedling is to improve drug delivery, which has shown promising results with TXA in previous studies.13 This has been challenged by Kuster et al.,19 who demonstrated that TXA through microneedling did not bring about any additional benefit to the treatment of melasma; nonetheless, they first performed microneedling and then applied TXA. Contrarily, Ebrahim et al.20 showed that microneedling of TXA was as safe and effective as its intradermal injection with higher patient satisfaction with microneedling, which is in line with our findings. Much similar to our study, Budamakuntla et al.14 compared TXA microinjections with TXA mesoneedling and, at odds with our results, reported significantly better improvement with microneedling. Overall, the difference in the TXA concentration, the route of administration, characteristics of the study populations, efficacy assessment tools, the number of treatment sessions, and the interval between two treatments can account for the discrepancy in the results of these studies.

Of note, there appears to be a potential contradiction; although complications were more frequent with TXA mesoneedling, patients were more satisfied with this treatment method. The patients have seemingly graded their satisfaction based on the improvement of melasma, regardless of the accompanying adverse events.

Intradermal injection of TXA led to better results compared with its topical application in Egyptian melasma patients.21 However, the superiority of the intradermal over the topical route was not confirmed in the systematic review and meta-analysis by Feng et al.1 Intradermal TXA injection has also shown promising results in comparison with Erbium-YAG laser.22 Intralesional TXA has been reported to be superior to cryotherapy regarding both safety and efficacy.23 On the other hand, microneedling with TXA yielded better but not statistically significant results compared to microneedling with vitamin C.24 In another study, local infiltration of TXA combined with 4% hydroquinone resulted in significantly better outcomes than hydroquinone alone,25 showing the efficacy of TXA as an adjunct therapy.26

Another finding of the current study was the significantly higher frequency of complications, including erythema, edema, and scaling with TXA mesoneedling vs. TXA microinjections. On the contrary, no significant adverse effects were observed with microneedling in the study by Ebrahim et al.20 as well as the study by Budamakuntla et al.14 This can be justified by the lower concentration of TXA in their study.

Noteworthy, lack of a universally acceptable treatment for melasma may have affected our study,4 in that it is better to allocate an arm of a clinical trial to standard treatment and compare the new method with the existing one.

The major strength of our study was its split-face design, which makes the two groups homogeneous in terms of the potential influencing and confounding factors to a great extent. Nonetheless, this study was not without limitations. Our relatively small sample size makes the results subject to overestimation, while limiting the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, since both treatments were applied in each individual patient and due to the nature of the interventions, blinding of the patients was not possible. This may have biased the results of patient satisfaction. Furthermore, all patients received hydroquinone cream as baseline treatment; therefore, we cannot determine how much of the treatment response can be attributable to the interventions. Finally, all our participants were female and mostly had Fitzpatrick skin type II. The results may have been affected by this. Also, the effects of the interventions on male patients and other Fitzpatrick skin types are unknown.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Overall, TXA mesoneedling was comparable with TXA microinjection in the treatment of facial melasma evaluated by improvement in mMASI, while patient satisfaction was significantly higher with TXA mesoneedling. Still, the high frequency of complications occurring with this treatment should be taken into account and TXA mesoneedling should be used with caution in patients with facial melasma. Although erythema, scaling, and edema may be temporary, PIH can be difficult to treat. Larger randomized controlled trials with longer follow-up periods are required to determine the true effects of each therapeutic option, especially in the long term. Also, randomized trials with a control arm receiving hydroquinone alone can determine the add-on effect of these interventions or their true effect.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

NP contributed to conceptualization and study validation. MA contributed to implementation and supervision. ZS contributed to data analysis and interpretation. FFN and MA contributed to writing and reviewing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely appreciate the dedicated efforts of the investigators, the coordinators, the volunteer patients, and the personnel of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences Dermatology Clinic.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences funded the current study.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The patient whose images are presented in the manuscript gave us consent for their publication.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study received ethics approval from the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences under the ethics code: IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.743, and it complies with the statements of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients. The trial has also been registered while recruiting at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), IRCT20201205049603N1, available at https://www.irct.ir/trial/52773.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.