Vaping and dynamic risk construction: Toward a model of adolescent risk-related schema development

Abstract

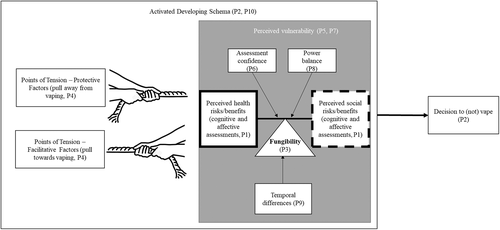

Adolescents experience vulnerability because their brains are not fully developed and they have limited knowledge and experience, inhibiting their ability to assess and mitigate risks. Drawing on literature from different disciplines, this paper develops a model that illustrates the dynamic nature of information and experience acquisition and ongoing risk and benefit assessment. New concepts are created to reflect better adolescent risk-related schema: fungibility, fog of vulnerability, and points of tension, all of which are useful in understanding how intentions and in-the-moment decisions are made in the context of vaping.

Ask any teenager; adolescence is complicated. Rapid changes are occurring physically, emotionally, and socially impacting adolescents' decision-making. Teens find themselves straddling childhood and adulthood, often being faced with making adult-like decisions while still having childish impulses.

Compared to adults, adolescents are considered vulnerable for two reasons: (1) Their brain is not fully developed until approximately age 25, inhibiting decision-making based on evaluations of benefits and risk (Pechmann, 1997) and inhibiting and influencing how schemas are developed (Cook et al., 2021); and (2) They have limited experience, which further inhibits their ability to mitigate risks and risky situations (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019). As Cauffman (2004) elegantly stated, “this period may be one of opportunity, in which steps may be taken to promote positive development” (p. 160), emphasizing that these vulnerabilities explain but do not excuse risky behavior.

Adolescents' decision to engage in or abstain from problem behaviors, such as vaping, involves navigating health risks, social risks, financial risks, and others, a task for which they may be ill-equipped. To make matters more challenging, decisions that seem obvious to adults may loom with considerable risks for some adolescents (Mason et al., 2013). At the same time, other choices with consequences dismissed by adults are perceived as benefits by adolescents. For example, turning down an opportunity to use e-cigarettes can cause negative short-term social consequences for some adolescents, such as being bullied by those who do, but not necessarily for adults. Further, teens may find that escaping one threat requires accepting another; for example, a teen may accept a vape pen to appear to be joining in with the group and thus be able to turn down alcohol later.

Additionally, research often ignores adolescents' varying situational, environmental, and contextual factors and their different personalities, capabilities, and deficiencies. They are a heterogeneous population (e.g., Jordan et al., 2019); thus, taking a person-centered approach can aid in understanding their risk/benefit conundrum, the challenge of navigating multiple risks and benefits with very different consequences and temporal outcomes.

This paper develops a conceptual model of adolescent risk assessment, integrating threat, vulnerability, and schema-based approaches to create a person-centered view (Lanza et al., 2010) that represents the dynamic, or ongoing, sensemaking by adolescents as they encounter threats and opportunities. This approach considers the entire range of risk factors, contexts, and characteristics that contribute to adolescent risk assessment and acknowledges that these factors rarely function separately (Cicchetti, 1993). The resulting model of risk schema construction addresses the experience/knowledge source of adolescent vulnerability.

We selected e-cigarette usage as the focal behavior because it comes with multiple risks and benefits, interacts with personal and situational variables that include other risks, and incorporates a temporal element of consumption and consequence, thereby benefiting from a person-centered risk assessment model. E-cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product among adolescents (Cherian et al., 2020). In addition, vaping marijuana is a new trend among adolescents, with 23% of high school adolescents using e-cigarette devices to vape marijuana (Miech et al., 2020).

We begin with a review of vaping risks to adolescent health. Recent consumer vulnerability research offers needed insights into adolescents' heuristics to recognize and cope with risks. Perceived vulnerability has a rich history of study that supports a person-centered approach; these research areas are integrated into an expectancy framework that can be applied to understand competing risks when considering a single decision made repeatedly over time.

1 E-CIGARETTES AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH

E-cigarettes are smoke-free products among popular teen smokers (Glasser et al., 2021). Vaping initiation among adolescents starts at 13–16 years old, with Hispanic and Black adolescents more prone to start earlier than other adolescents (NYTS, 2020). More than one in four adolescents under 18 years old have tried vaping products and demonstrate a greater preference (81%) for vaping products with nicotine as the main ingredient (NYTS 2020). These outcomes are attributed to e-cigarette brands' increased marketing expenditures (Collins et al., 2019) and how governments have obviated the heavy restrictions imposed on traditional cigarette advertisements, such as a ruling by the US Court of Appeals that struck down strict rules proposed by the FDA (Passport Euromonitor, 2011).

E-cigarette manufacturers make two common advertising claims. The first is that e-cigarettes help smokers quit tobacco products, which is a common reason to begin vaping among tobacco users (Tomkins et al., 2021). The second is that e-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes, a belief widely held among teenage consumers (Buckell et al., 2019). Adolescent consumers perceive vaping as trendy, fashionable, and cool (Giovacchini et al., 2017); are motivated by the availability of flavors (Groom et al., 2021); are influenced by peers (Groom et al., 2021); and view e-cigarettes as a stress management tool (Cooper et al., 2016). Despite counter-efforts (i.e., FDA's “The Real Cost” campaign targeting adolescents in schools and online) to inform adolescent consumers of the health risks associated with e-cigarette use, two-thirds of adolescent JUUL users are not fully aware that these products always contain nicotine (CDC, 2021). Consequently, many adolescents report dependence symptoms from e-cigarette use and seek support for vaping cessation (Sanchez et al., 2021).

E-cigarette consumption is increasing despite evidence that vaping products include a concentration of tobacco-related toxins that harm consumer wellbeing and safety (Goniewicz et al., 2018). Apart from nicotine, which is present in 99% of vaping products, the liquids and aerosols used in vaping devices contain harmful substances that can produce brain damage, harm the respiratory system, and negatively affect mood and individuals' self-control (CDC, 2021). These risks are not solely for e-cigarette users, as passive smokers can suffer the health risks linked to e-cigarettes (Visser et al., 2019). Moreover, e-cigarette liquids have poisoned children and adults, while defective e-cigarette devices have caused explosions and fires (CDC, 2021).

The widespread marketing of e-cigarettes is linked to a wide range of population-level health effects, depending on dual consumption of traditional cigarettes and e-cigarettes, levels of use, and product toxicity (Kalkhoran & Glantz, 2015). There are at least five categories of health risks, including nicotine addiction, brain diseases, altered memory capacity, probability of cancer, and cardiovascular/pulmonary illnesses. A summary of the health risks associated with vaping is presented in Table 1.

| Type of health risk identified in the study | Method | Summary of conclusions | Adolescents' knowledge of related health risks | FDA warning requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular health risks (Alzahrani et al., 2018; Antoniewicz et al., 2019; Peruzzi et al., 2020) | Systematic review; experimental study; survey data | E-cigarette use is associated with tachycardia, increased blood pressure, myocardial infarction, and arterial stiffness. | Young consumers do not know about the vascular health risks associated with nicotine, solvents, and flavorings that e-cigarettes use (MacDonald & Middlekauff, 2019). | Not addressed |

| Nicotine addiction and subsequent use of traditional cigarettes (Boakye et al., 2020; Miech et al., 2017; Soneji et al., 2017) | Review; meta-analysis; longitudinal study | Individuals learn traditional cigarette-related behaviors and scripts that make the transition to cigarette smoking more natural. | Adolescents perceive e-cigarettes having no nicotine (Roditis & Halpern-Felsher, 2015). | Addresseda |

| Brain development (Boakye et al., 2020; Tobore, 2019) | Systematic review | Negative effects on learning, attention, and memory | Adolescents do not know the long-term effects of oxidative stressb (Tobore, 2019). | Not addressed |

| Probability for the development of abnormal cells and cancer (Kosmider et al., 2014; Pankow et al., 2017) | Laboratory tests | Chemicals found on vaping products include carcinogenic compounds and metals that can affect organ systems | Adolescents' increased use of new generation e-cigarette devices is associated with lower long-term perceived risks (e.g., oral cancer or lung cancer) (McKelvey et al., 2018). | Not addressed |

| Pulmonary illnesses and lung diseases (Besaratinia & Tommasi, 2020; Layden et al., 2020; Maddock et al., 2019) | Medical record abstraction and interviews; Clinical records; Report | Patients present respiratory distress after using e-cigarettes | Adolescents have misperceptions about e-cigarette harm. However, social media messages led to greater knowledge about the harms of e-cigarettes (e.g., lung damage, valor contains chemicals; Lazard, 2021). | Not addressed |

- a Current FDA's required warning statement only addresses nicotine risk “WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical” (U.S. FDA, 2020).

- b Oxidative stress is a molecular factor that drives the harmful effects that vaping may cause. Oxidative stress has been linked to cognitive deficits, memory impairment, sleep disorders, and depression (Tobore, 2019).

Adolescents are also heavily influenced by peer pressure, which subsequently influences the take-up of vaping (Roditis et al., 2016; Roditis & Halpern-Felsher, 2015). Socially, tobacco use can be seen as a rite of passage for adolescents, and the social implications are seen as good reasons for using tobacco products (Yang et al., 2013). As the number of friends who smoke increases, so does the probability of an adolescent smoking (Yang & Netemeyer, 2015; Yang & Schaninger, 2010). Indeed, how adolescents identify with macro-level teen subcultures influences substance use based on the norms of that sub-culture (Jordan et al., 2019).

Adolescents who do not take up behaviors that mark them as members of an in-group will suffer risk consequences ranging from teasing to bullying and social isolation. These consequences, linked to vaping avoidance (e.g., Patterson et al., 2020), can lead to depression and suicide. At the same time, peer acceptance moderates the emotional health consequences of other factors, such as the effect of harsh parenting on depression (e.g., Tang et al., 2018). Adolescent depression and peer victimization have been shown to have lifelong consequences (e.g., Copeland-Linder et al., 2010). Studies further show that extreme social isolation during adolescence has a lasting effect on brain structure, leading to more habit-based addictive behaviors (Hinton et al., 2019). Thus, the social risk of (not) vaping can range from mild to significant, impacting adolescents' mental health.

Adolescence is a time for change and growth; adolescents in their earlier teenage years may become significantly different in just a year as they develop physically and cognitively (Yang & Schaninger, 2010). Thus, trying to fit adolescent decision-making into a standard variable-centric approach reduces our ability to understand the decisions and behaviors of adolescents. With a person-centered approach to developing a theoretical framework, the variety of benefits and risks of vaping and the different types of e-cigarettes lumped into one product category make this behavior particularly well-suited as an exemplar for the study of managing competing risks and rewards. The following section discusses the nature of risk and schemas potentially associated with vaping. Figure 1 illustrates our proposed conceptualization of how adolescents' developing schema and vulnerability influence the decision to vape.

2 RISK SCHEMA CONSTRUCTION

Schemas are multifaceted cognitive structures that organize and retain knowledge and influence one's view of the world (Preston et al., 2017). Schemas also include the emotional response to said information or during the experience (Lowenstein et al., 2001). However, due to immature hippocampal binding processes (Pudhiyidath et al., 2020) and medial temporal lobe and medial prefrontal cortex development limitations, adolescents acquire and apply schemas differently than adults (Cook et al., 2021).

When faced with vaping decisions, these brain development limitations result in over-reliance on the amygdala and emotions (Arnsten & Shanksy, 2004), including emotions stored as information (Lowenstein et al., 2001). When an opportunity arises to vape, adolescents' current schema influences engagement in those behaviors. Those behaviors then reinforce that schema, which leads to more or less vaping behavior (Stein et al., 1998).

The traditional view of perceived risk having only two cognitive dimensions: probability and severity (Rogers, 1997)—limits understanding of how adolescents build a vaping schema. Responses to threats, especially for adolescents, integrate emotions with cognitive processes, and thus guide judgments (Slovic et al., 2002). For adolescents, the system applied is a type of affect heuristic (Finucane et al., 2000) demonstrated by studies that observe how emotional reactions to cigarette warning labels (e.g., fear, disgust) drive intentions (Netemeyer et al., 2016), which in turn informs schema construction.

Andrews et al. (2019) found that text plus graphic health warning (text+GHW) had the greatest effect on the intention to vape over text-only messages. This effectiveness occurs because the reliance on emotion-as-information adds to the strength of the schema, consistent with Netemeyer et al.'s (2016) findings of emotions as mediators of messages. As anti-vaping strategies trigger emotions that engage risk assessments and influence intentions, those emotions become information in the schema, consistent with Andrews et al.'s (2016) findings concerning message-created emotions a week after exposure.

Further, individuals pay attention to anticipatory emotions like anxiety and fear when risk assessments are made (Lowenstein et al., 2001). These anticipatory emotions may be triggered when offered an e-cigarette, enabling recall of the immediate visceral reactions to risks posed in earlier messaging even if not (yet) felt in the moment. Extensive studies in psychology show that the emotional reactions happening at the moment of accepting or rejecting an offer to vape become drivers of later behaviors (Slovic et al., 2002). We emphasize the moment as those anticipatory emotions are stored as part of the schema and influence later decisions, including decisions to attend risky situations knowingly.

Gaps in schema contribute to an over-reliance on feelings in risk assessments. Gaps in adolescents' schema are filled over time by learning through modeling, social interactions, and reinforcement (Moore et al., 2002). Modeling involves adolescents' observation and imitation of others' behavior. Adolescents' social interactions with others in various contexts, such as parents, teachers, or peers, and reinforcement through reward or punishment used by significant others, such as peers, can drive adolescents vaping choices. Through these learning modes, peers or other significant others exert influence on adolescents.

This process is idiosyncratic, supporting a person-centric approach. Schema-building begins long before someone offers an e-cigarette, such as watching a video on vaping at school or ‘having the talk’ with parents (Yang et al., 2019). Each interaction with vaping information comes with an assessment. Adolescents then build a risk schema over time, anchoring various risks of vaping based on their relationship to other risks, and associating behaviors and products with those risks. For example, an adolescent may know that tobacco product use is contrary to good health. However, they have also seen e-cigarette companies' marketing images promoting the behavior (Berry & Burton, 2019), observed cool young people vaping, and the possible taboo nature may appeal to their desire to rebel. These factors may lead to an assessment of risk and benefit that favors vaping (Berry & Burton, 2019).

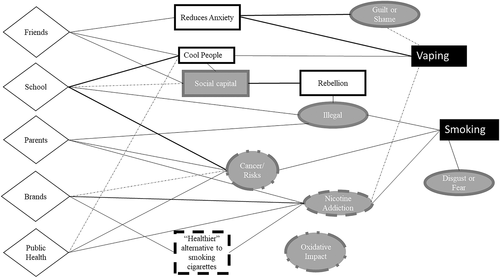

As illustrated in the example of an incomplete schema in Figure 2, vaping may be more closely associated with cool people than with parents (assuming parents abstain and encourage abstention). This association increases the salience of short-term social risk and decreases the salience of longer-term health risk. Trade-off analysis may occur when new information is presented, old information is reinforced, or at the decision point for selecting a behavior, reflecting a schema involving both cognitive and affective risks. Further, different conditions may yield different outcomes, especially as the schema is adjusted based on new information and experience.

A risk-as-feelings assessment often focuses on the here-and-now, making vaping's immediate consequences far more salient than longer-term health consequences, noted as perceived health and social risk/benefits in Figure 1. For example, adolescents may be more likely to rely on social cues than prior cognitive risk assessments in an environment of only people perceived as cool. In building the vaping schema, an adolescent's anticipatory feelings of social rejection from an aspirant social group (Kiat et al., 2018) may derail the best-laid plans of anti-vaping promoters and even the intentions of that adolescent at the time health-risk information is presented.

P1.: Risk/benefit assessment includes cognitive and affective assessments that can occur simultaneously or in various patterns depending on the schema activated at that moment.

P2.: The schema activated at the decision-making point determines which risks and benefits are most salient and influence adolescents' decision to vape. Gaps in schema lead to over-reliance on affective assessments.

2.1 Fungibility of risk/benefit

The development of a vaping risk/benefit schema relies on a concept we wish to introduce, the fungibility of risks. In economics, fungible assets are identical in value and traded equally. For example, a one-dollar coin and a one-dollar bill are fungible, having an identical value that does not require any assessment. If we consider fungibility in risk/benefit assessment as a matter of degree, then fungibility can be thought of as an assessment of the degree to which one risk/benefit can be substituted for another. For that reason, we depict fungibility as a fulcrum in Figure 1. Research on adolescent risk trade-offs is minimal but what has been examined is a preference for a given risk or benefit when a trade-off can be made (Rohde & Rohde, 2015). Netemeyer et al. (2015) observed that as the need for affiliation rose, risk perceptions of prescription drug abuse declined, which may have been an example of the fungibility between social acceptance and health risks. These studies show that risks and rewards are considered and traded by adolescents. The mechanisms by which adolescents assess whether a vaping risk or benefit can be traded for another are poorly understood. However, fungibility is central to understanding adolescent vaping behavior and the dynamic of risk construction as they build their schema.

As illustrated in Figure 1, a single risk component (e.g., a vaping health risk) may have a fixed score in the adolescent's mind, while another component may vary depending on conditions (e.g., who is present, a social risk). Fungibility does not mean equal or near-equal scores; instead, risks/benefits can be traded when conditions align to maximize reward or minimize negative consequences. Thus, fungibility estimates the degree of equivalency that changes as new information and experience are gathered, including situational conditions, and represents a processing shortcut for in-the-moment choice.

The fungibility of vaping's health risks and social benefits are weighed when information is received, often before an e-cigarette is offered. When the e-cigarette is offered, an adolescent's risk schema is accessed. A prior assessment of fungibility may be perceived as salient, then modified based on situational information such as the power balance between the tempter and the tempted adolescent. That adolescent evaluates the risk of the direct threat (e.g., probability and severity of health-related outcomes) resulting in a fixed score, as well as the perceived risk of indirect threats (e.g., social risk) resulting in a variable score dependent upon situational factors. Figure 1 illustrates the direct and relatively fixed (for the moment of temptation) vaping health risk/benefit as a solid outline, while the situationally-influenced social risk/benefit of vaping is variable and outlined with a dashed line.

For example, some adolescents perceive anxiety-reduction benefits in vaping (McKelvey et al., 2018), against which they are willing to trade off the possible longer-term negative consequences. If social risks/benefits accrue, adolescents tend to vape in a limited fashion to control health consequences and only with specific friends to maximize social benefits. Depending on individual factors such as need for affiliation, the social risk may increase or decrease in salience, changing the fungibility score. Once all factors are assessed, fungibility can be considered a score against which vaping can be compared to similar behaviors with the same categories of risk and benefit. Then, in a given moment, if risks and benefits are traded, those scores can be weighted by the conditions of the setting, resulting in a choice that differ across individuals, depending on the richness of their schema, the salience of variables, and other individual characteristics.

P3.: A dimension of risk schema is the fungibility relationship between risks and benefits assessed as the schema is constructed, which varies based upon individual and situational characteristics, and can influence choice at the presentation of a risky opportunity.

2.2 Points of tension

Points of tension occur when the trade-offs are unclear and/or insufficiently fungible. Borrowing from physics, these factors exert force, pulling teens toward a particular direction (c.f. Woodward, 2007). Points of tension can include protective or facilitative factors related to genetics, social environment, family relationships, school environment, or peer relationships (Jessor, 1992). Additionally, personality factors, such as risk tolerance, sensation-seeking, and need for affiliation, may also act as points of tension, pulling the adolescent either toward engaging in or away from vaping behaviors (see Figure 1).

These protective or facilitative factors are engaged in creating, applying, and adjusting the risk schema, as illustrated in Figure 1. Further, points of tension can protect the risky behavior in certain situations but facilitate it in others, and what is protective for some adolescents might not be for others (Blum et al., 2002). For example, parental relationships can act as a protective factor when parents discuss the health risks or other reasons not to vape (Yang et al., 2019). Conversely, parental relationships can be a facilitative factor for adolescents whose parents vape, giving implicit approval to use such products. Additionally, adolescents can have strong family relationships, but if e-cigarette use is not discussed, family relationships may not influence the schema on vaping. In risk schema creation, we propose that points of tension are applied in assessing the salience, fungibility, and likelihood of risks.

P4.: Points of tension are factors, such as protective/risk factors and personality, applied when assessing the salience, fungibility, and likelihood of risks.

Over time, assessments occur as information is gathered. Ultimately, a rich structure of experiences and information is constructed that aids in assessment, precisely the type of structure adolescents have not yet built. Adolescents lack a deep and broad schema due to their lack of experience, creating vulnerability (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019), so integrating an understanding of adolescent vulnerability is essential for a risk assessment model.

2.3 Adolescent vulnerability

Due to their inexperience and incomplete brain development, adolescents construct risk and perceive vulnerability in situations differently than adults. Consumer vulnerability is the recognition that one is in “a state of powerlessness that arises from an imbalance in marketplace interactions or from the consumption of marketing messages and products” (Baker et al., 2005, p. 134) and that lack of power increases the perceived probability and/or severity of a negative outcome (Tanner Jr. & Tanner, 2020).

Adolescents' lack of knowledge and experience with vaping causes over-weighing personal and social benefits while under-weighing potential social and health risks (Ciranka & van den Bos, 2021). Adolescents are far more experienced in recognizing immediate social benefits, whereas health risks are far off in the future. However, recent research shows that real risk varies by age and circumstance (Skrzypiec et al., 2019), as do perceptions of vulnerability (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019).

Perceptions of vulnerability reduce individuals' willingness to acquiesce with organizations that address a particular vulnerability through risk aversion and temporal orientation (Tanner & Su, 2019), affect their adoption of preventative health behaviors (Tanner et al., 2020), and may increase the salience of risk-as-feelings. For some adolescents, vaping ameliorates anxiety (Cooper et al., 2016) and facilitates coping with peer-induced vulnerability (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019).

When individuals feel vulnerable, they can fall prey to the fog effect, which we define as the inability to think clearly and act independently of those who may impose risks, illustrated by the gray box in Figure 1. This effect can be short-lived, operating only as long as the perception of vulnerability lasts. Therefore, when an adolescent encounters powerful peers pushing vaping, the fog effect clouds one's ability to recognize risks fully and leads to over-or under-weighing some forms of risk in assessing fungibility.

How confident one is in one's assessment accuracy can also vary (Mourali & Yang, 2013). Confidence, or the lack thereof, may lead to applying different heuristics to fungibility. For example, a lack of confidence in one assessment may yield greater intentions of mitigating a competing but well-known risk; alternatively, two competing and low confidence assessments may result in greater emotion-based judgment. Assessment confidence influences perceptions of vulnerability, and even inappropriate over-confidence can lift the fog, though perhaps not with the best decisions.

Recall that adolescents are in a dynamic, ongoing process of building a schema of risks/benefits and the relationships between them. Vaping may not be the threat over which mastery is needed; social consequences of (not) vaping may be entangled with other threats, which can also reflect vulnerability imposed by powerful others (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019).

P5.: Vulnerability reduces confidence in risk assessment and increases risk-as-feelings judgments, enhancing the salience of short-term or better-known risks/benefits, which tend to be social and can be ameliorated by choosing to vape.

P6.: The convergence of vulnerability perception and fungibility assessment leads to risky behaviors, such as vaping. Adolescents engage in cognitive and affective risk/reward assessments to address perceived vulnerability, and this process can generate other perceptions of vulnerability.

P7.: Perceived vulnerability inhibits adolescents' ability to accurately judge risks involved with vaping (the fog effect) and limit their ability to seek support to cope with sources of vulnerability.

P8.: Restoring adolescents' power balance over the threat reduces the impact of vulnerability on risk assessment and provides tools to reduce the threats in healthy ways.

P9.: Adolescents adopt schema-building strategies to fill gaps in existing schemas, including deliberate risk-taking, information seeking, and reliance on others, and are a function of age and individual factors.

2.4 Temporal factors

The temporal occurrence of cognitive and affective risk assessment heightens the importance of understanding fungibility in schema. The Ordered Protection Motivation model (Tanner Jr. et al., 1991) suggests that presenting threat information first creates fear (an emotional response) which then heightens attention to coping information, consistent with Kees et al.'s (2010) findings that fear-mediated the influence of GHW. Further, the relationships generally held among young adult smokers a week after viewing warning messages (Andrews et al., 2019). An important function of schema construction is the retention of information, and how emotions such as fear are stored and recalled is important to understand if one hopes to influence a decision long after a message is received.

The mixture of threat and benefit information in vaping marketing reduces the efficacy of both; benefit information reduces the threat's efficacy while threat warnings reduce the efficacy of the benefit (Berry & Burton, 2019). How the order effects of messaging and information-gathering operate, along with the effect of time on message decay (Dunlop et al., 2013) needs study, as reflected in the Temporal Differences box in Figure 1 illustrating the impact on fungibility and schema development.

A mismatch between perceived vulnerability and objective risk likely occurs when temporal differences between benefits and consequences are greatest. Accepting the probability of negative vaping consequences (e.g., lung cancer) when they are far in the future (a dashed outline in Figure 2) may be difficult because adolescents have limited life experience with which to compare, especially when those who have experienced negative outcomes are generations older and not easily seen as a referent case. Moreover, adolescents tend to overestimate their probability of early mortality (Zimmerman et al., 2016), which may explain why some discount health threats that manifest much later in life. Benefits, such as social rewards, are more immediate (a solid outline in Figure 2) and, therefore, may be more desirable.

In contrast, adolescent cigarette smokers may experience immediate benefits from switching to e-cigarettes (George et al., 2019). Adolescents choosing to vape for these benefits may respond to strategies that address short-term risks by enhancing assessments or creating new or adding to nodes in their schema, improving fungibility accuracy. Examples in the sample schema in Figure 2 include the relationship between nicotine and addiction (shown as weakly related to vaping), the risk of brain damage due to the oxidative effect (shown as unknown by the gray shape and lack of any relationships), and feelings of guilt or shame (illustrated as related to vaping and anxiety but not well understood prior to vaping). Thus, schemas are built by enacting short-term strategies and gaining experience, which may explain some deliberate risky behavior (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019), chosen to gain the necessary knowledge with which to build out a schema. Further, relying again on Figure 2 to provide an example, if guilt or shame were felt, that shape would become more apparent and relationships more clearly understood, held in the individual's schema as anticipatory emotions should temptation arise again.

Adolescents who perceive health and/or social risks also weigh situational characteristics differently depending on their perceived vulnerability. A source of perceived vulnerability is the recognition of a lack of knowledge (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019). When adolescents recognize they lack knowledge and/or experience that makes them vulnerable, they can adopt strategies that avoid deliberate risk-taking. Strategies such as information search to reduce the knowledge gap, relying on the perceived expertise of friends, and other strategies that plug those schema gaps (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019).

P10.: Temporal differences make immediate outcomes more salient compared to outcomes that are in the future, a trade-off that affects fungibility.

3 DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The dynamic risk construction model shows how adolescents' incomplete schemas and vulnerability impact their susceptibility to vaping. This novel approach to adolescent risk management contributes several new concepts to theory. The first, fungibility, represents the outcome of a trade-off assessment of one risk/benefit for another, often made prior to temptation and adjusted based on situational information. The second is points of tension that either facilitate risk-taking or protect adolescents from gaps in their schema. The third, the fog of vulnerability, a form of cognitive paralysis that occurs when one recognizes one's vulnerability, alters how risk is processed at the moment. Thus, this proposed framework has several implications for theory and practice.

Teenagers, particularly younger teenagers, do not have the brain development, experience, knowledge, and other tools to effectively weigh the benefits and risks of vaping, and they know it (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019). Exploring how the various types of vulnerability contribute to adolescents' fungibility assessment, particularly for miscalculation of risk, is an opportunity for future research. Identifying the impact of vulnerability reduction can promote healthy schema development and better choices. How to best lift that fog is unclear other than developing confidence by additional information that plugs gaps in the schema or by relying on peer experts (Batat & Tanner Jr, 2019), but what happens when the vulnerability is imposed, and expertise is not available? Further research on the impact of perceived vulnerability on risk assessments and decision-making should be explored.

3.1 Marketing and policy implications

With the exponential market growth of e-cigarettes and related vaping products and the complex array of threats and possible benefits, vaping provides a valuable context for drawing recommendations for applying this model. Increased adolescent use can be attributed to soft regulations imposed by the FDA on e-cigarette advertising campaigns that heavily reach youth audiences (Farrimond, 2016). Formal debate on regulations is needed among e-cigarette manufacturers, media, regulators, public health agencies, and consumer groups.

Marketing campaigns position e-cigarettes as cost-effective, high-tech, trendy, and socially acceptable products (Majmundar et al., 2020). Typical claims include: (a) e-cigarettes provide better taste options (Berry & Burton, 2019); (b) vaping makes people look attractive and trendy (Maloney & Cappella, 2016); and (c) e-cigarettes are cost-effective (Wackowski et al., 2019). Health-related claims are also featured in e-cigarette campaigns, including (a) e-cigarettes help smokers quit tobacco products, a common reason to begin vaping among tobacco users (Tomkins et al., 2021); and (b) e-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes, a belief widely held among younger consumers (Buckell et al., 2019).

Given the variety of pro- and anti-messaging campaigns reaching adolescents and the FDA required warning label that only mentions addiction, anti-vaping efforts are failing because: (a) current anti-e-cigarette marketing campaigns fail to recognize the risks that matter to adolescents (Berry & Burton, 2019); (b) adolescents automatically predict e-cigarettes and vaping products are safer than traditional cigarettes and this belief dominates their still-developing risk schema (Roditis & Halpern-Felsher, 2015); (c) perceived health risks are virtually indistinguishable and muddled, especially as the fog of vulnerability descends, resulting in fungibility assessments favoring better understood social risks (Roditis & Halpern-Felsher, 2015); and (d) adolescents' vulnerability due to their lack of power balance and temporal perspective related to the decision to vape. This research suggests that pro-vaping marketing campaigns that emphasize social acceptance, over-emphasize or fail to recognize temporal differences between risks and benefits, or address gaps in schema increase adolescent vaping; therefore, regulating these campaigns is essential.

Moreover, the FDA should consider online and in-store information sources used by adolescents when considering vaping and regulate the messages presented. The Real Cost campaign includes online and social media elements; the FDA could require manufacturers to direct adolescents to those sites and eliminate confusing and questionable information such as the social acceptability of vaping and its impact on anxiety. Supported by prior research, which indicates that fear leads to information seeking (Tanner Jr. et al., 1991), an example might be a graphic instore warning with a Q.R. code that takes the adolescent to more information.

Adolescence is a time of rapid development, constant assessment of risks/benefits available, and growing self-awareness of one's limitations. These factors make understanding risk assessment from the adolescent's perspective of paramount importance for scholars, policymakers, and marketers. The addition of fungibility, points of tension, and the fog of vulnerability add to that understanding and should provide guidance for addressing adolescent development in risk avoidance.