Vonoprazan non-inferior to lansoprazole in treating duodenal ulcer and eradicating Helicobacter pylori in Asian patients

Trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03050359 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03050359).

Declaration of conflict of interest: Liqun Gu is an employee of Takeda Development Center Asia; Chui Fung Chong was an employee of Takeda Development Center Asia and is a stock shareholder in Air Liquide and Abbott Laboratories; Kentarou Kudou is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Japan; and Xiaohua Hou, Fandong Meng, Jiangbin Wang, Weihong Sha, Cheng-Tang Chiu, Woo Chul Chung, and Shutian Zhang have nothing to disclose.

Author contribution: Conceptualization by SZ, XH, JW, CFC, WS, C-TC, LG, and KK; data curation by XH, KK, SZ, FM, JW, WS, LG, and CFC; formal analysis by KK, SZ, XH, JW, WS, C-TC, and CFC; investigation by SZ, FM, JW, WS, XH, C-TC, WCC, LG, and CFC; methodology by JW, CFC, XH, WS, C-TC, LG, KK, and SZ; project administration by WS, FM, JW, CFC, and SZ; resources by FM, WS, LG, CFC, and SZ; software by SZ; supervision by SZ, XH, JW, WS, WCC, and LG; validation by SZ, XH, JW, WS, C-TC, LG, and CFC; visualization by XH, JW, WS, C-TC, LG, CFC, and SZ; writing original draft by SZ, XH, JW, WS, and CFC; and reviewing and editing by LG, SZ, XH, FM, CFC, JW, WS, C-TC, WCC, and KK.

Financial support: Takeda Development Center Asia Pte. Ltd. sponsored the study and supplied all the drugs used in the study. Takeda was also involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Xiaohua Hou and Shutian Zhang had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data, and the accuracy of the data analysis. Medical writing assistance was provided by Magdalene Chu and Marissa Scandlyn of MIMS (Hong Kong) Ltd., which was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., China.

Abstract

Background and Aim

Duodenal ulcers, especially caused by increasingly drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori, are a concern in Asia. We compared oral vonoprazan versus lansoprazole for efficacy (healing duodenal ulcers) and safety in non-Japanese Asian patients.

Methods

In this phase 3, randomized (1:1), double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, non-inferiority study (April 5, 2017, to July 19, 2019), patients with ≥ 1 endoscopically confirmed duodenal ulcer, at 52 hospitals (China, South Korea, and Taiwan), received vonoprazan 20 mg once daily (QD) or lansoprazole 30 mg QD for 6 weeks maximum. Patients with H. pylori received bismuth-containing quadruple therapy including vonoprazan 20 mg twice daily (BID) or lansoprazole 30 mg BID, for 2 weeks, followed by vonoprazan or lansoprazole monotherapy QD (4 weeks maximum). Endpoints were endoscopically confirmed duodenal ulcer healing (Week 4/6; primary) and H. pylori eradication (4 weeks post-treatment; secondary); non-inferiority margins were −6% and −10%, using a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Of 533 enrolled patients, one was lost to follow-up and one withdrew (full analysis set: 531 patients [vonoprazan, n = 263; lansoprazole, n = 268]; 85.4% = H. pylori positive). Vonoprazan was non-inferior to lansoprazole for duodenal ulcer healing (96.9% vs 96.5%; difference 0.4% [95% CI −3.00, 3.79]). H. pylori eradication rates were 91.5% (vonoprazan) and 86.8% (lansoprazole; difference 4.7% [95% CI −1.28, 10.69]). Vonoprazan and lansoprazole were well tolerated, with similar safety profiles, no new safety signals; no deaths occurred.

Conclusions

Vonoprazan was well tolerated and non-inferior to lansoprazole for duodenal ulcer healing and achieved H. pylori eradication above the clinically meaningful threshold (90%), in non-Japanese Asian patients.

Introduction

Peptic ulcer disease is characterized by acid-induced lesions in the gastroduodenal mucosa.1 Duodenal ulcers are associated with nocturnal abdominal pain,1 chronic nausea,2 reduced quality of life,3 and economic burden for patients and healthcare systems.4, 5 Peptic ulcer disease is more prevalent in Asian than Western populations,6-8 and the fatality rate remains high at approximately 3–10%.1, 5 Helicobacter pylori infection is a major risk factor for gastric or duodenal ulcers, contributing to an estimated 85% of cases.1, 6, 9 An epidemiologic study found that 93% of Chinese patients with peptic ulcer disease had H. pylori infection.6 H. pylori infection is associated with a sixfold increased risk of developing gastric cancer,10 and H. pylori antibiotic resistance is increasing,11 especially in Asia where clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance rates are high (> 15%).12-14

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), such as lansoprazole, which suppress gastric acid secretion by inhibiting hydrogen/potassium adenosine triphosphatase (H+/K+ ATPase) enzymes in the gastric mucosa, are the current standard of care for peptic ulcer disease.15, 16 However, their efficacy is limited by a short half-life, pre-prandial dosing, and considerable inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetics related to cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 polymorphisms.1, 16 Vonoprazan is a potassium-competitive acid blocker that reversibly inhibits H+/K+ ATPase and does not require acid activation,17, 18 offering faster and longer suppression of gastric acid secretion than PPIs.17, 19 Vonoprazan is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4/5 and to a lesser extent by CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6. Genetic polymorphisms have a limited effect on vonoprazan pharmacokinetics.19 Although limited data are available, a Japanese study found no significant differences in the eradication rate among CYP3A5 and CYP2C19 genotypes in clinical outcome of vonoprazan-containing triple eradication therapies in H. pylori-positive patients.20

Vonoprazan 20 mg was also non-inferior to lansoprazole 30 mg as a component of first-line triple therapy with amoxicillin and clarithromycin for H. pylori eradication therapy in patients with cicatrized peptic ulcer disease in another phase 3 study in Japan.21 In a phase 3 study in Japan, vonoprazan 20 mg once daily was non-inferior to lansoprazole 30 mg once daily in endoscopic healing of duodenal ulcers after 6 weeks of treatment in the per-protocol analysis.22 However, there remains a need to examine effectiveness in other populations, including those treated and diagnosed in line with Chinese guidelines,13 which include 2-week eradication quadruple therapy for H. pylori-positive patients.

Here, we aimed to assess whether vonoprazan is non-inferior to lansoprazole for ulcer healing in a non-Japanese Asian population of patients with endoscopic evidence of duodenal ulcers with or without H. pylori infection.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, non-inferiority study in Asian patients with duodenal ulcers with or without H. pylori infection. Patients were planned to be enrolled at 68 hospitals in China, South Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines.

This study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation: Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and all applicable regulations and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review board approval was obtained from all study centers before study initiation. The study was prospectively registered before the first patient was enrolled (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03050359). All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Participants

Eligible patients were male or female, aged 18 years or older, with endoscopic evidence of at least one active duodenal ulcer with a minimum diameter of 5 mm within 14 days before randomization. H. pylori infection was confirmed by 13C urea breath test. Detailed exclusion criteria are provided in Table S1.

Patients were not permitted to consume medication that may interfere with H. pylori urea breath testing within 14 days of screening; non-study-related PPIs and H2 receptor antagonists within 14 days of screening; antibiotics, anti-protozoals, non-study-related H. pylori eradication therapy, medications contraindicated with clarithromycin, or strong CYP3A4 inducers within 30 days of screening; or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), agents affecting digestive organs, or medications contraindicated with vonoprazan or bismuth from the start of study treatment. Female patients agreed to use adequate contraception throughout the duration of the study.

Study procedures

Eligible patients were randomized (1:1) via an interactive web-response system, stratified by H. pylori status, to vonoprazan or lansoprazole groups (Fig. S1). Patients with confirmed H. pylori infection were administered oral vonoprazan 20 mg twice daily or oral lansoprazole 30 mg twice daily, with matching placebo, in combination with bismuth-containing quadruple eradication therapy (amoxicillin 1 g twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, and bismuth potassium citrate/bismuth tripotassium dicitrate 600 mg twice daily) for 2 weeks, which was recommended by the “Fourth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection.”23 After eradication therapy, patients continued treatment with vonoprazan 20 mg once daily or lansoprazole 30 mg once daily for up to 4 weeks. Patients without H. pylori infection received vonoprazan 20 mg once daily or lansoprazole 30 mg once daily for up to 6 weeks. Patients remained in the same treatment group throughout the study. All patients and investigators were blinded to treatment allocation. Blinding of the study medication was achieved by use of double dummies whereby patients self-administered a tablet and a capsule at each dosing time point.

Endoscopic healing was defined as disappearance of all white coating associated with duodenal ulcers. Patients with evidence of endoscopic healing at Week 4 or 6 entered a follow-up period up to 4 weeks or until serum gastrin-17 levels and pepsinogen I/II ratio recovered. Patients without endoscopic healing at Week 6 discontinued treatment and entered a follow-up period. All patients with H. pylori infection at baseline had a follow-up 13C urea breath test at 4 weeks post-treatment.

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with endoscopically confirmed healing of duodenal ulcers at Week 4 or 6. Secondary endpoints included proportion of patients with endoscopically confirmed healing of duodenal ulcers at Week 4; proportion of H. pylori-positive patients who achieved successful H. pylori eradication after 4 or 6 weeks of treatment; and proportion of patients with post-treatment resolution of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms associated with duodenal ulcers at Weeks 2–6.

Additional pre-specified endpoints included health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measurements (assessed using the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-5 Levels [EQ-5D-5L] questionnaire and the Euro Quality of Life visual analogue scale [EQ VAS]), and the proportion of patients with endoscopically confirmed healing of duodenal ulcers at Week 4, and Week 4 or 6 by H. pylori status at baseline and 4 weeks post-treatment.

Safety assessments included adverse events (AEs; coded according to MedDRA version 22.0), clinical laboratory tests, electrocardiogram, vital signs, physical examinations, and serum gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I/II levels.

Statistical analyses

The study planned to enroll at least 265 patients (including 238 Chinese patients) per study group to provide more than 80% power to establish non-inferiority for endoscopically confirmed healing rates of duodenal ulcers using a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) with a −6% non-inferiority margin. The sample size was estimated based on the assumption that the true duodenal ulcer healing rate at Week 6 would be 95.5% for both vonoprazan and lansoprazole, with a dropout rate up to 10%.

Efficacy variables were analyzed using the full analysis set (all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug) according to the original randomization. All randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug were included in the safety analysis set. Sensitivity analyses were also performed using the per-protocol set (all patients included in the full analysis set who had no major protocol deviations) to examine the robustness of the results.

Post-treatment GI symptoms were recorded daily in patients' diaries as none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, or severe = 3; mean severity for each patient was calculated. Frequency distributions, rates, and two-sided 95% Wald CIs were calculated for each symptom.

Patients with missing endoscopy data from the evaluation period were excluded from analyses of primary and secondary endpoints. Details of the statistical analyses are provided in Table S1. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question, nor were they involved in the design and implementation of the study. No plans exist to involve patients in dissemination of the results.

All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Patients

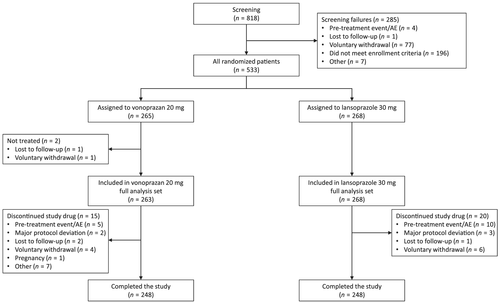

In total, 533 patients from 52 hospitals in China, South Korea, and Taiwan met the criteria for randomization (Fig. 1). No eligible patients were enrolled at hospitals in the Philippines. The majority (95.1%) of patients were enrolled from China (Table 1). Patients were enrolled from April 5, 2017. The last patient contact was on July 19, 2019. The study stopped when the protocol-defined patient number data collection was reached. The full analysis set comprised 531 patients (99.6%; Table S2), with 263 patients randomized to the vonoprazan group and 268 to the lansoprazole group. One patient was lost to follow-up (0.2%) and one patient withdrew from the study (0.2%) before administration of the first dose of study drug. Overall, 496 (93.1%) patients completed the study (vonoprazan 93.6% [248/265], lansoprazole 92.5% [248/268]). The most common reason for discontinuation was a pretreatment event or AE (2.8%, n = 15).

| Vonoprazan 20 mg (n = 265) | Lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 268) | Total (n = 533) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 42.0 (12.18) | 41.4 (12.89) | 41.7 (12.53) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 166 (62.6) | 176 (65.7) | 342 (64.2) |

| Female | 99 (37.4) | 92 (34.3) | 191 (35.8) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 22.87 (3.37) | 22.83 (3.18) | 22.85 (3.27) |

| Country/regions, n (%) | |||

| China | 252 (95.1) | 255 (95.1) | 507 (95.1) |

| South Korea | 10 (3.8) | 8 (3.0) | 18 (3.4) |

| Taiwan | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.9) | 8 (1.5) |

| Helicobacter pylori infection status,†n (%) | |||

| Positive | 226 (85.3) | 229 (85.4) | 455 (85.4) |

| Negative | 37 (14.0) | 38 (14.2) | 75 (14.1) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Never smoked | 164 (61.9) | 165 (61.6) | 329 (61.7) |

| Current smoker | 86 (32.5) | 84 (31.3) | 170 (31.9) |

| Ex-smoker | 15 (5.7) | 19 (7.1) | 34 (6.4) |

| Duodenal ulcer characteristics | |||

| Type of ulcer, n (%) | |||

| Primary | 230 (86.8) | 227 (84.7) | 457 (85.7) |

| Recurrent | 35 (13.2) | 41 (15.3) | 76 (14.3) |

| Location,‡n (%) | |||

| Superior, including bulb | 262 (98.9) | 266 (99.3) | 528 (99.1) |

| Descending portion | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) |

| Median number of ulcers (range) |

1 (1–3) n = 263 |

1 (1–5) n = 268 |

1 (1–5) n = 531 |

| Ulcer morphology, n (%) | |||

| Circular | 110 (41.5) | 117 (43.7) | 227 (42.6) |

| Ellipsoid | 109 (41.1) | 107 (39.9) | 216 (40.5) |

| Other | 46 (17.4) | 44 (16.4) | 90 (16.9) |

| Ulcer size, n (%) | |||

| Miniscule, < 5 mm | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Minor, ≥ 5 and < 10 mm | 183 (69.1) | 188 (70.1) | 371 (69.6) |

| Intermediate, ≥ 10 and ≤ 20 mm | 81 (30.6) | 78 (29.1) | 159 (29.8) |

| Large, > 20 and < 30 mm | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Giant, ≥ 30 mm | 0 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2) |

| Time since onset of current ulcers, days, mean (SD) |

2.4 (2.73) n = 262 |

4.3 (23.14) n = 267 |

3.4 (16.56) n = 529 |

| Time since onset of recurrent ulcers, days, mean (SD) |

1149.3 (910.72) n = 18 |

999.7 (828.57) n = 21 |

1068.7 (859.12) n = 39 |

| Use of NSAID or low-dose aspirin§ at time of onset of ulcer, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| No | 264 (99.6) | 266 (99.3) | 530 (99.4) |

| EQ-5D-5L score, mean (SD) |

0.94 (0.06) n = 263 |

0.94 (0.07) n = 268 |

0.94 (0.06) n = 531 |

| EQ VAS score, mean (SD) |

85.7 (10.43) n = 263 |

86.3 (12.00) n = 268 |

86.0 (11.24) n = 531 |

- † Missing data from two patients in the vonoprazan 20 mg group and one patient in the lansoprazole group.

- ‡ Missing data from one patient in the lansoprazole group.

- § Excluding topical administration.

- BMI, body mass index; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-5 Levels; EQ VAS, Euro Quality of Life visual analogue scale; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SD, standard deviation.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were comparable between treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, 85.4% (n = 455) of patients were H. pylori positive at baseline. Duodenal ulcers were predominantly circular or ellipsoid (83.1%, n = 443), primary ulcers (85.7%, n = 457), located in the superior region of the duodenum (99.1%, n = 528), and of 5–10 mm in diameter (69.6%, n = 371). Mean time to onset of current ulcers was slightly longer in the lansoprazole group (4.3 vs 2.4 days), whereas that of recurrent ulcers was almost 5 months longer in the vonoprazan group (1149.3 vs 999.7 days). Treatment compliance was similarly high (98.7%) between treatment groups (vonoprazan, 98.1%; lansoprazole, 99.3%).

Disease activity assessments

The proportions of patients with endoscopically confirmed healing of duodenal ulcers at Week 4 or 6 were 96.9% (246/254) and 96.5% (246/255) in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively (Table 2). The primary endpoint of vonoprazan non-inferiority versus lansoprazole for endoscopic healing of duodenal ulcers at Week 4 or 6 was demonstrated (between-group difference 0.4% [95% CI −3.00, 3.79]; Table 2) and confirmed in the per-protocol sensitivity analysis (Table S3). The proportions of patients with endoscopically confirmed healing of duodenal ulcers at Week 4 were 89.2% (222/249) and 88.4% (222/251) in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively (difference 0.7% [95% CI −4.90, 6.32]; Table 2).

| Vonoprazan 20 mg (n = 263) | Lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 268) | |

|---|---|---|

| Week 4 or 6 (primary endpoint) | ||

| Healed, n/N (%) | 246/254 (96.9) | 246/255 (96.5) |

| Difference versus lansoprazole† (95% CI) | 0.4 (−3.00, 3.79) | |

| Week 4 (secondary endpoint) | ||

| Healed, n/N (%) | 222/249 (89.2%) | 222/251 (88.4%) |

| Difference versus lansoprazole† (95% CI) | 0.7 (−4.90, 6.32) | |

- † Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by baseline Helicobacter pylori status; two-sided 95% CIs were calculated using the Newcombe method.

- CI, confidence interval.

Duodenal ulcer healing rates were comparable between treatment groups irrespective of H. pylori status at baseline (Table S4) or 4 weeks post-treatment (Table S5). However, higher healing rates were observed with vonoprazan treatment at Week 4 or 6 among the relatively few patients who were H. pylori negative at baseline (97.2% [35/36] vs 88.9% [32/36]) and at Week 4 among patients who remained H. pylori positive 4 weeks post-treatment (94.1% [16/17] vs 77.8% [21/27]).

Vonoprazan was non-inferior to lansoprazole for H. pylori eradication at 4 weeks post-treatment in patients who were H. pylori positive at baseline (Table 3). Successful H. pylori eradication (assessed by 13C urea breath test at 4 weeks post-treatment) was achieved in 91.5% (193/211) and 86.8% (177/204) of patients in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively (treatment difference 4.7% [95% CI −1.28, 10.69]).

| Vonoprazan 20 mg (n = 211) | Lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 204) | |

|---|---|---|

| H. pylori eradicated, n/N (%) | 193/211 (91.5) | 177/204 (86.8) |

| Difference versus lansoprazole,† (95% CI) | 4.7 (−1.28, 10.69) | |

- † Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by baseline Helicobacter pylori status; two-sided 95% CI was calculated using the Wald method.

- CI, confidence interval.

Both vonoprazan and lansoprazole had favorable effects on GI symptoms (Table S6). Resolution rates exceeded 80% and were comparable between treatment groups. No differences in HRQoL were observed between treatment groups (Table S7). EQ-5D-5L values changed minimally over 6 weeks of treatment (mean [standard deviation] change from baseline at Week 6 was 0.052 [0.0555] and 0.056 [0.0594] in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively; P = 0.8187). EQ VAS scores improved over time but remained comparable between treatment groups (mean [standard deviation] changes from baseline at Week 6 were 8.6 [10.82] and 9.4 [10.49] in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively; P = 0.7764).

Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were comparable across treatment groups and generally mild or moderate in severity (Table 4). At least one TEAE was reported by 74.1% (195/263) and 64.9% (174/268) of patients in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively. At least one treatment-related TEAE was reported by 60.5% (n = 159) and 37.7% (n = 101) of patients in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively. AEs considered related to other constituents of H. pylori eradication therapy (i.e., clarithromycin, amoxicillin, or bismuth potassium citrate/bismuth tripotassium dicitrate) comprised 21.6–27.8% of incidents.

| Vonoprazan 20 mg (n = 263) | Lansoprazole 30 mg (n = 268) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE, n (%) | 195 (74.1) | 174 (64.9) |

| Related to vonoprazan or lansoprazole | 159 (60.5) | 101 (37.7) |

| Related to clarithromycin | 73 (27.8) | 66 (24.6) |

| Related to amoxicillin | 65 (24.7) | 58 (21.6) |

| Related to bismuth | 68 (25.9) | 63 (23.5) |

| Severity, n (%) | ||

| Mild | 130 (49.4) | 140 (52.2) |

| Moderate | 54 (20.5) | 32 (11.9) |

| Severe | 11 (4.2) | 2 (0.7) |

| TEAEs leading to study drug discontinuation, n (%) | 5 (1.9) | 10 (3.7) |

| Related to vonoprazan or lansoprazole | 4 (1.5) | 6 (2.2) |

| Serious TEAEs, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Related to vonoprazan or lansoprazole | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Related to clarithromycin | 0 | 0 |

| Related to amoxicillin | 0 | 0 |

| Related to bismuth | 0 | 0 |

| Leading to study drug discontinuation | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs reported by ≥ 5% of patients, n (%) | ||

| Investigations | 152 (57.8) | 86 (32.1) |

| Pepsinogen test positive | 124 (47.1) | 28 (10.4) |

| Pepsinogen I increased | 92 (35.0) | 37 (13.8) |

| Blood gastrin increased | 97 (36.9) | 20 (7.5) |

| Protein urine present | 20 (7.6) | 11 (4.1) |

| ALT increased | 12 (4.6) | 17 (6.3) |

| Infections and infestations | 30 (11.4) | 49 (18.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 21 (8.0) | 37 (13.8) |

| Nervous system disorders | 28 (10.6) | 33 (12.3) |

| Dysgeusia | 21 (8.0) | 22 (8.2) |

- ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

The most common TEAEs were pepsinogen test positive (47.1%), blood gastrin increased (36.9%), and pepsinogen I increased (35.0%) in the vonoprazan treatment group, and pepsinogen I increased (13.8%) and upper respiratory tract infection (13.8%), followed by pepsinogen test positive (10.4%) in the lansoprazole group. Treatment-related diarrhea was slightly more common among patients in the vonoprazan group (1.5%) than in the lansoprazole group (0.4%). Fifteen (2.8%) patients discontinued treatment owing to AEs; four (1.5%) in the vonoprazan group and six (2.2%) in the lansoprazole group.

Incidence of serious AEs (SAEs) was similar between treatment groups (0.4% [n = 1] and 1.1% [n = 3] in the vonoprazan and lansoprazole groups, respectively; Table 4). One SAE in the lansoprazole group was considered related to study drug and all others were unrelated.

No clinically significant changes occurred in laboratory, electrocardiogram, vital signs, or physical examination data. Mean levels of serum gastrin and pepsinogen I and II increased in both treatment groups, although to a greater extent in the vonoprazan group (Table S8) but resolved on completion of study drug administration. Both treatment groups showed similar changes in pepsinogen I/II ratio.

Four pregnancies were reported during or after the study, one in the vonoprazan group (unrelated, elective abortion) and three in the lansoprazole group (one related, spontaneous abortion and two unrelated, normal deliveries).

Discussion

Vonoprazan was non-inferior to lansoprazole for endoscopic healing of duodenal ulcers after 4 or 6 weeks of treatment in a mainly Chinese patient population, providing the first evidence of vonoprazan non-inferiority to a PPI at healing duodenal ulcers in a full analysis set. Previously, a Japanese phase 3 study found similar results after 6 weeks of treatment, but non-inferiority was only demonstrated in the per-protocol population owing to a high early treatment discontinuation rate in the vonoprazan group.22 Furthermore, treatment with vonoprazan was associated with healing rates of over 95% among patients with H. pylori-positive duodenal ulcers. Given the high prevalence of H. pylori-positive patients with duodenal ulcers, particularly in Asia,24 our study supports the use of vonoprazan in non-Japanese Asian patients with duodenal ulcers.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates for patients administered vonoprazan-based quadruple therapy were also non-inferior to lansoprazole-based therapy. Eradication rates in the vonoprazan group exceeded 90%, which is deemed a clinically relevant threshold for determining the efficacy of H. pylori eradication regimens.25 H. pylori eradication rates above this level limit additional treatment needs and reduce risk of secondary antibiotic resistance; hence, vonoprazan-based quadruple therapy may be preferable to lansoprazole-based therapy when treating H. pylori-positive duodenal ulcers, particularly in Asian populations, in which antibiotic resistance is prevalent.25

The efficacy of vonoprazan at eradicating H. pylori has been reported previously.21, 26-28 Vonoprazan demonstrated non-inferiority versus lansoprazole as a component of first-line triple therapy with amoxicillin and clarithromycin in Japanese patients with cicatrized peptic ulcers and also in patients infected with a clarithromycin-resistant strain.21 Recently, dual therapy with vonoprazan plus amoxicillin was reported to be non-inferior to vonoprazan-based triple therapy for H. pylori eradication.28 Moreover, a meta-analysis has reported superiority of a vonoprazan-based regimen over a PPI-based regimen for H. pylori eradication.26, 27 The potent gastric acid-inhibitory effect of vonoprazan and its slow clearance from the gastric gland are considered to provide an optimal environment for antimicrobials to exert their effect,21 but further investigation is required.

Notably, H. pylori eradication rates are reported to be significantly higher with vonoprazan than with lansoprazole among patients infected with clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori.21 This is relevant given the resistance of H. pylori to antibiotics, particularly in Asia.11, 14 Because H. pylori eradication rates are declining as the prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains increases,29 vonoprazan-based regimens may provide an effective alternative to PPI-based triple therapy. Additionally, empiric treatments to eradicate H. pylori are important in populations with a relatively high risk of gastric cancer,12 such as Asian patients.30

The safety and tolerability results for vonoprazan reported in the current study are consistent with previous findings, with no new safety signals identified. The incidence of TEAEs was slightly higher in the vonoprazan than the lansoprazole group, which was higher than the prevalence previously observed in Japanese patients; however, the incidence of SAEs was comparable.22 Notably, our study included a 2-week eradication period for H. pylori-positive patients, during which time patients received vonoprazan or lansoprazole twice daily in combination with antibiotic therapies, which may have contributed to the higher incidence of TEAEs.

Although the incidence of study drug-related TEAEs was higher in the vonoprazan than lansoprazole group, this appeared to be driven by a higher prevalence of increases in positive pepsinogen tests, pepsinogen I levels, and serum gastrin levels, which is consistent with previous reports for vonoprazan.21, 22 Increases in serum gastrin and pepsinogen I and II levels are a physiological response to gastric acid suppression and pH elevation among gastric contents. Changes were observed in both study groups, and mean levels of gastrin and pepsinogen I and II returned to baseline levels once study drug administration ceased. Furthermore, although the incidence of drug-related diarrhea was slightly higher in vonoprazan-treated patients, no incidences of drug-related gastrin increase, pepsinogen I, or diarrhea resulted in study drug discontinuation.

Reassuringly, efficacy and safety results for vonoprazan here translated into improved patient-reported outcomes, with most patients reporting resolution of any GI symptoms associated with duodenal ulcers during their 2–6 weeks of treatment. No significant differences were observed between treatment groups and HRQoL measures remained comparable throughout the study, with minimal changes in EQ-5D-5L, but improved EQ VAS scores.

This study has a few limitations. One is the absence of data on antibiotic-resistance profiles of H. pylori in infected patients. The other is that CYP2C19 genotyping, which may have affected lansoprazole activity, was not evaluated. These limitations are, however, balanced by multiple strengths: an Asian patient population with and without H. pylori infection, endoscopically assessed ulcer healing and H. pylori eradication endpoints, and patient-reported outcomes.

Vonoprazan 20 mg was non-inferior to lansoprazole 30 mg for duodenal ulcer healing after 4 or 6 weeks of treatment in non-Japanese Asian patients and was well tolerated. Vonoprazan was also non-inferior to lansoprazole for H. pylori eradication and was associated with an eradication rate above the clinically meaningful threshold of 90%. These findings suggest that vonoprazan offers an effective treatment alternative to PPIs for H. pylori eradication and duodenal ulcer healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients and their families who participated in this trial, all investigators, and the Takeda and IQVIA (contract research organization) 304 study team for their valuable involvement in this study. Medical writing assistance was provided by Magdalene Chu and Marissa Scandlyn of MIMS (Hong Kong) Ltd., which was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., China, and complied with Good Publication Practice 3 ethical guidelines.31

Data access, responsibility, and analysis

Transparency declaration

Shutian Zhang, Liqun Gu, and Kentarou Kudou affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data transparency statement

The datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual patient data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within 3 months of initial requests to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after its de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection, and requirements for consent and anonymization. Proposals should be directed to Liqun Gu ([email protected]). Data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

License for publication

The corresponding author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a worldwide license to the publishers and its licensees in perpetuity, in all forms, formats, and media (whether known now or created in the future), to (i) publish, reproduce, distribute, display, and store the contribution, (ii) translate the contribution into other languages, create adaptations, reprints, include within collections, and create summaries, extracts, and/or abstracts of the contribution, (iii) create any other derivative work(s) based on the contribution, (iv) to exploit all subsidiary rights in the contribution, (v) the inclusion of electronic links from the contribution to third-party material wherever it may be located; and (vi) license any third party to do any or all of the above.