Long-term course of inflammatory bowel disease after the Great East Japan Earthquake

Abstract

Background and Aim

This study analyzed inflammatory bowel disease activity for 2 years after the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Methods

We compared the relapse rates of patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease 1 and 2 years after the earthquake with rates immediately after the earthquake. To evaluate continuous disease courses, we also performed multivariate time-to-event analyses from the time of the earthquake to the onset of additional treatments.

Results

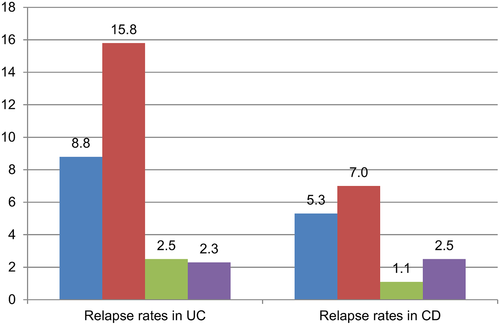

Of 903 patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease in our previous study, we could evaluate 2-year courses in 677 patients (394 ulcerative colitis and 283 Crohn's disease). Compared with the relapse rates of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease immediately after the earthquake (15.8% and 7.0%, respectively), those in the corresponding periods in 2012 (2.5% and 1.1%, respectively) and 2013 (2.3% and 2.5%, respectively) significantly decreased. There were 226 patients who required additional treatments after the earthquake. Multivariate time-to-event analyses revealed that only patients who had experienced the death of family members or friends were likely to need additional treatments (hazard ratio = 1.77, 95% confidence interval = 1.25–2.47). No other factors had a significant influence.

Conclusions

The relapse rates 1 and 2 years after the earthquake significantly decreased. The factors that influenced long-term relapse were different from those that influenced short-term relapse.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD), is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gut that often exhibits a remitting/relapsing course. Although the triggers for relapse in patients with IBD have not been ascertained, factors such as stress can play a significant role and lead to an inappropriate immune response that produces chronic inflammation.1-11

We previously reported that life-event stress induced by the Great East Japan Earthquake was associated with relapse in patients with UC but not CD.12 Multivariate analysis identified factors that were associated with relapse: IBD type (UC in comparison with CD), changes in dietary oral intake, and anxiety about family finances. However, in that study, we followed patients with IBD for only a total of 4 months before and after the earthquake. Some patients relapsed several months after the earthquake.

In this retrospective cohort study, we evaluated the disease activities of patients with IBD for up to 2 years after the earthquake. We compared the relapse and remission rates 1 and 2 years after the earthquake with those immediately after the earthquake. To evaluate the continuous disease courses, we also performed multivariate time-to-event analyses from the time of the earthquake to the onset of additional treatments.

Methods

Study subjects

The present long-term follow-up study included patients with UC or CD who were treated at 13 hospitals (Tohoku University Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital, Sendai Medical Center, Takagi Clinic, Osaki Citizen Hospital, Sendai City Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Sendai Hospital, Miyagi Cancer Center, South Miyagi Medical Center and Kesennuma City Hospital in Miyagi Prefecture, Iwate Prefectural Isawa Hospital, Iwate Prefectural Chubu Hospital, and Iwate Prefectural Iwai Hospital in Iwate Prefecture) in areas that were severely affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011. In our previous study, we examined the disease activities of 903 patients with UC or CD in the 2-month period before and in the 2-month period after the earthquake.12 In the present study, we sent these patients a follow-up questionnaire after careful informed consent was established with each patient. We asked physicians to check the medical records of the patients for up to 2 years after the earthquake.

Similar to our previous study, we evaluated the disease activity using the partial Mayo score for UC and the Harvey–Bradshaw Index for CD.13, 14 Similar to our previous study, “active” was defined as follows: a partial Mayo score ≥ 2 (UC) and a Harvey–Bradshaw index ≥6 (CD). Lower scores indicated inactive disease. We defined “relapse” as a change from inactive to active and “remission” as a change from active to inactive across 2 months before and 2 months after the earthquake.12 We compared the relapse and remission rates 1 and 2 years after the earthquake with those immediately after the earthquake.

We also asked physicians to check the medical records about additional medical treatments for UC or CD after the earthquake, including the use of medications [prednisolone, azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, infliximab (IFX), adalimumab, tacrolimus (TAC), or adjustments of doses of oral or topical 5-aminosalicylic acid], total parenteral nutrition, elemental diet, cytapheresis (CAP), or surgery. We performed time-to-event analyses that included all possible variables. Detailed definitions of the variables, such as IBD type, sex, age, disease duration, extra-intestinal complications, which were obtained from physicians and smoking status, damage to houses, temporary homelessness, death of family members (second-degree relatives or siblings) or friends, complete loss of job, anxiety about family finances, changes in daily dietary intake, and discontinuation of medications, which were obtained from the patients, were described in our previous study.12

Statistical analysis

We evaluated differences between groups using chi-square test or Fisher's exact probability test, unpaired t test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as appropriate. To perform time-to-event analyses, we used log–rank test or Cox's proportional hazards model, as appropriate. We defined time as the time from the earthquake to the onset of additional medical treatments. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP version 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Relapse and remission rates after the earthquake

In our previous study, the disease activities of 903 patients with IBD (546 UC and 357 CD patients) were analyzed. Among these patients, we could evaluate 2-year courses of 677 patients with IBD (394 UC and 283 CD patients), and the rate of follow-up was 71.2%. In the 2-month period after the earthquake in March 2011, the relapse rates for UC and CD were 15.8% and 7.0%, respectively.12 In the corresponding period (March to May) in 2012, there were 10 UC [2.5% (10/394)] and three CD [1.1% (3/283)] patients with relapse. Similarly, in the corresponding period in 2013, there were nine UC [2.3% (9/394)] and seven CD [2.5% (7/283)] patients with relapse. The patients with UC and CD exhibited the relapse rates in 2012 and 2013 that were significantly lower than those immediately after the earthquake (Fig. 1).

, 2010;

, 2010;  , 2011;

, 2011;  , 2012;

, 2012;  , 2013.

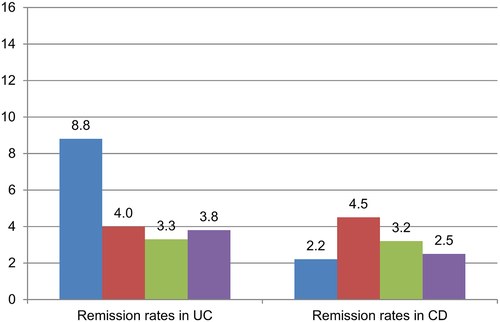

, 2013.With respect to remission, in the 2-month period after the earthquake, the remission rates for UC and CD were 4.0% and 4.5%, respectively.12 In the corresponding period (March to May) in 2012, the remission rates for UC and CD were 3.3% (13/394) and 3.2% (9/283), respectively. Similarly, in the corresponding period in 2013, the remission rates for UC and CD were 3.8% (15/394) and 2.5% (7/283), respectively. There were no significant differences between the remission rate immediately after the earthquake and those in 2012 or 2013 (Fig. 2).

, 2010;

, 2010;  , 2011;

, 2011;  , 2012;

, 2012;  , 2013.

, 2013.Additional treatments during 2 years after the earthquake

There were 226 patients who required additional treatments for UC or CD in the 2-year period after the earthquake. The mean duration from the earthquake to the onset of additional medical treatments was 21.8 months. Among those 226 patients, 44 received prednisolone, 31 received azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine , 63 received IFX, 32 received adalimumab, 17 received TAC, 82 received adjustments of doses of oral or topical 5-aminosalicylic acid, 23 underwent CAP, 6 received total parenteral nutrition, 8 received elemental diet, and 26 underwent surgery.

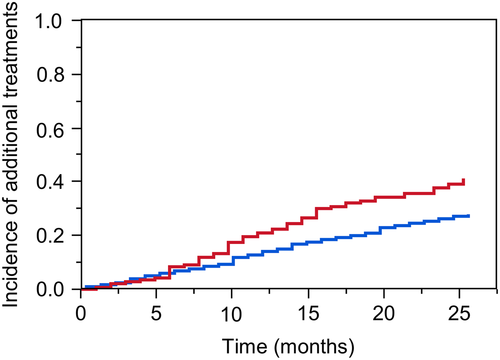

Using Cox's proportional hazards model, we determined that patients who had experienced the death of family members or friends because of the earthquake were likely to need additional treatments. These patients exhibited a significant hazard ratio of 1.77 [95% confidence interval = 1.25–2.47]. No other factors had a significant influence on the time-to-event analyses (Table 1).

| N | Hazard ratio | P value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD type | ||||

| Ulcerative colitis | 394 | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.58–1.06 |

| Crohn's disease | 283 | 1.0 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 393 | 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.63–1.14 |

| Female | 284 | 1.0 | ||

| Age | ||||

| >40 years | 322 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.56–1.04 |

| ≤40 or less | 355 | 1.0 | ||

| Disease duration | ||||

| >10 years | 272 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.69–1.26 |

| ≤10 or less | 405 | 1.0 | ||

| Extra-intestinal complications | ||||

| Positive | 62 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.61–1.61 |

| None | 615 | 1.0 | ||

| Smoking status† | ||||

| Current smokers | 98 | 1.14 | 0.50 | 0.76–1.67 |

| Others | 578 | 1.0 | ||

| Damage to houses† | ||||

| Total or half loss | 106 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.62–1.46 |

| Others | 502 | 1.0 | ||

| Temporarily homelessness† | ||||

| ≥1 week | 50 | 1.05 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.85 |

| Others | 623 | 1.0 | ||

| Death of family members or friends† | ||||

| Yes | 139 | 1.70 | <0.01 | 1.20–2.36 |

| None | 532 | 1.0 | ||

| Complete loss of job† | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.47–1.59 |

| None | 631 | 1.0 | ||

| Anxiety about family finances† | ||||

| Yes | 232 | 1.0 | 0.99 | 0.72–1.37 |

| None | 443 | 1 | ||

| Changes in daily dietary intake† | ||||

| Yes | 205 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.72–1.35 |

| None | 468 | 1.0 | ||

| Discontinuation of medications | ||||

| ≥1 week | 50 | 0.70 | 0.24 | 0.35–1.25 |

| None | 627 | 1.0 | ||

- CI, confidence interval; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

- † Information on several patients regarding smoking status, damage to houses, temporarily homelessness, death of family members or friends, complete loss of job, anxiety about family finances, and changes in daily dietary intake was not available.

We divided patients into the following two groups: patients who had experienced the death of family members or friends because of the earthquake and those who had not. On comparing both groups, the incidence of additional treatments was significantly higher among those who experienced earthquake-related loss of a family member or friend (log–rank test P < 0.001, Fig. 3).

, Patients who had experienced the death of family members of friends because of the earthquake;

, Patients who had experienced the death of family members of friends because of the earthquake;  , Others.

, Others.Discussion

The Great East Japan Earthquake caused great damage and daily life hardships as well as profound stress for those populations directly affected. It was an extremely stressful life event and might have contributed to relapses in patients with IBD. As mentioned in our previous study, the activity scores of patients with UC significantly increased after the earthquake, and the relapse rate immediately after the earthquake was about twice that of the corresponding period in the previous year.12 Several months after the earthquake, remarkable post-disaster restoration of the patients' environment was evident. This included increasing food supplies, housing, and public transportation. The period of food scarcity was not very long, and unemployed patients found new jobs. That might be one of the reasons why the relapse rates 1 and 2 years after the earthquake were significantly lower than those observed immediately after the earthquake. As the living environment was restored, environmental stressors likely decreased. The patients at risk of relapse might have experienced relapse immediately after the earthquake, also resulting in lower relapse rates 1 or 2 years after the earthquake. Improvement and advances in IBD treatments after the earthquake might have played a key role on lower relapse rates. However, treatment options (IFX, TAC, CAP, etc.) did not greatly change during the 2-year period.

On the other hand, the activity scores of patients with CD slightly (but not significantly) increased immediately after the earthquake.12 However, 1 and 2 years after the earthquake, the relapse rates of CD decreased as did those of UC. The earthquake had a great impact on patients with CD as well as UC but not sufficiently enough to make a significant difference as in UC.15-17

Regardless of a remarkable restoration of the living environments, some patients with UC or CD relapsed outside the examination periods. There may be factors that cannot be grasped in fragmentary surveys 1 and 2 years after the earthquake. Therefore, in order to evaluate the continuous course of these diseases, we also performed continuous time-to-event analyses considering additional medical treatments. Multivariate time-to-event analyses revealed that only patients who had experienced the death of family members or friends because of the earthquake were likely to need additional treatments. No other factors had a significant influence.

In our previous multivariate analyses, IBD type (UC), changes in oral intake, and anxiety about family finances were independent predictors of relapse immediately after the earthquake.12 We considered that psychological stress from changes in daily life or uneasiness about the future have a greater effect on UC relapse than direct damage and losses. In fact, there are some reports that patients with IBD (particularly with UC) are readily influenced by stress and are likely to fall into depression or relapse.18-25 On the other hand, in the present study, those factors had no significant influence on continuous time-to-event analyses. Although statistical methods used in the present study (logistic regression method) were different from that in our present study (Cox's proportional hazards model), only the death of family members or friends was significantly associated with additional medical treatments. Immediately after the earthquake, stress from the earthquake itself and that from changes in daily life caused short-term relapse because of their enormity. With a remarkable restoration in patients' living environments, stress from the earthquake itself and that from changes in daily life might have decreased. Stress from the death of family members or friends may gradually have become larger and caused long-term relapse as long-term stress. Levenstein reported that the risk of relapse in patients with UC was increased by long-term stress, but not short-term stress.26 From numerous testimonies of those suffering from tragic events, deaths of intimates must be considered the most heartbreaking events that they can experience. However, immediately after the earthquake, patients might be desperate to survive the disaster. Therefore, the death of family members or friends had no significant influence on short-term relapse. On the contrary, the number of relapses in patients who have experienced the death of family members or friends increased from around 6 months after the earthquake.

The results of the present study might indicate that factors that influenced long-term relapse were different from those that influenced short-term relapse.

In the patients with IBD, relapse might be caused by some life events after the earthquake. Therefore, we also investigated life events after the earthquake. Beyond 2 months from the earthquake, there were 172 patients who experienced some life events. The life events were as follows: the death of family members or friends (n = 83), moving of residence (n = 62), giving birth/pregnancy (n = 16), resignation/work transfer (n = 14), family members' sickness or patient's own sickness (n = 9), marriage (n = 6), and others (n = 7). The relapse rates among those patients with some life events in 2012 or 2013 did not differ from those of all patients (data not shown). Contrary to our expectations, the life events had no significant influence on relapse 1 and 2 years after the earthquake. Compared with some life events such as the death by illness or senility, sudden death by the earthquake might have had a larger stress load.

This study had some limitations. First, we could evaluate the long-term courses in only 71.2% of patients who were investigated in our previous study. The reduced follow-up rate may potentially have influenced our study. However, it was impossible to trace some patients because they had changed hospitals, discontinued outpatient treatments, or had undergone surgery. Second, compared with the relapse and remission rates immediately after the earthquake, the rates 1 and 2 years after the earthquake might be fairly low. In our previous study, we investigated disease activities in the 2-month period before and in the 2-month period after the earthquake and calculated the relapse and remission rates immediately after the earthquake. Similarly, in the present study, the assessments of relapses and remissions were performed in the corresponding periods 1 and 2 years after the earthquake. However, those examination periods (a total of 4 months in 2012 and 2013) were not very long. Many patients relapsed or went into remission in the periods outside of those examination periods. Therefore, in order to evaluate continuous disease courses, we also investigated additional medical treatments after the earthquake and performed time-to-event analyses. Third, the timing and choice of additional treatments were mainly decided by physicians, resulting in information bias.

Most clinicians believe that stress in patients with IBD is a problem that cannot be ignored because of its impact on their disease courses. We hope that our results will be helpful for clinicians when considering the relationship between stress and disease courses of patients with IBD in clinical and research settings.