How should river embankments be spatially developed, from the upstream section or the downstream section?

Funding information: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Grant/Award Number: 21K18128

Abstract

Using an economic model of how river embankments affect local residents, we explore the efficiency of embankment construction from two viewpoints: (1) which section of a river should be constructed first, the upstream or downstream section, and (2) how tall the embankments should be constructed depending on the section. For this purpose, we first develop a model to determine efficient construction of embankments using a hydraulic model. Then, we perform numerical simulations, which are calibrated with recorded ground data for the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers. The results reveal that the construction from the upstream section can be efficient if the upstream section has a much larger population than the downstream section. We show that constructing higher embankments in the upstream section generates negative externalities in the downstream section because it increases the possibility of flooding in the downstream section. In addition, when the amount of inflow from tributaries into the downstream section is sufficiently large compared to that into the upstream section, embankments with efficient heights bring about Pareto improvements, giving benefit to residents in the downstream section as well as the upstream section. Moreover, we show that the efficient embankment heights depend on which section the construction starts from.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recently, due to torrential rains probably associated with climate change, serious flood damage has occurred in various regions all over the world. For example, in Japan, recent torrential rains, such as the “2020 July Rains” and the “2019 East Japan Typhoon,” have caused rivers to overflow and cities to be inundated, resulting in disasters. In Europe, in July in 2021, huge river floods in the Rhine river basin due to torrential rains caused the death of over 180 people. Such torrential rains are supposed to be caused by climate change. So, there is a possibility that the number of flood disasters will increase in the future.

To protect cities from such flood disasters, one typical measure is the construction of embankments (Nakamura & Oki, 2018). Depending on the progress of global warming, embankments may be added even in previously-improved rivers in some areas around the world. We explore the efficiency of embankment construction from two viewpoints: (1) which section of a river should be constructed first, the upstream section or the downstream section, and (2) how tall the embankments should be, depending on the section. Regarding the first point, it takes many years to finish constructing embankments for the whole river. So, which part of the river is improved first determines who benefits from the embankments. Regarding the second, because the heights of the embankments determine the expected costs of future inundation in the river basin, the heights are a significant factor.

In Japan, embankments are always constructed from the downstream section to the upstream section. The reason for adopting this order of construction is based on fairness, not efficiency, as explained below. If embankments are developed from the upstream unlike the current way, flooding in the upstream section will be prevented, but water that would have flooded in the upstream section will flow into the downstream section. In addition, as the depth of the water rises to a higher level in the upstream, the flow velocity increases and more water flows into the downstream section. Therefore, if the river protection is implemented in the upstream before in the downstream, the risk of flooding in the downstream section will increase before the construction of the downstream embankments. This can be considered unfair. In terms of economics, the construction of the upstream embankments generates a negative externality for the downstream residents. We use the term “fairness” as an indicator of how benefits differ across regions.

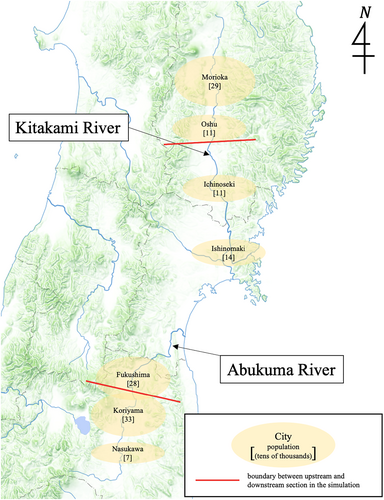

For these reasons, in Japan, it is an ironclad rule in flood control planning that improvements should be implemented from the downstream section. However, this rule leaves flood risks in the upstream section for a long time. Indeed, in the Kitakami River basin shown in Figure 1, river protections, which are ongoing, have been implemented from the downstream section to the upstream section. As a result, Morioka, which has the largest population along the river and is located in the upstream section, will be the last to have embankments built. At present, Morioka faces critical risks of flooding every time torrential rain falls.

Is it always right to have construction of embankments from the downstream section? Actually, not only fairness but also economic efficiency, which we define as cost-effectiveness in this paper, are important for designing policies. Needless to say, if the population is large in the upstream section, the construction of embankments from the upstream section is efficient.

The heights of embankments as well as the order of construction can be determined from the viewpoints of fairness and efficiency. However, in practice, the heights are not necessarily determined from these viewpoints. For example, in Japan, the target rainfall scale against which the embankments are constructed to prevent flooding completely is set for each river according to the importance of the river, such as the sizes of cities along the river, and past flooding records. The heights of the embankments are determined based on the target rainfall scale. For example, in the case of the Kitakami River, the target rainfall scale is set at the once-in-150-years level. As a result, the target heights are not necessarily efficient. Currently, Japan's method of cost–benefit analysis only confirms whether the cost–benefit ratio is more than 1.

There are many studies which explore the optimal heights of embankments from the viewpoints of efficiency based on a flood runoff model. However, the order of construction, the upstream section first or the downstream section first, has not been discussed.

Previous studies explore flood protection policies using cost–benefit analysis. For example, Zwaneveld et al. (2018) propose a model for a cost–benefit analysis to determine the efficient embankment height. Eijgenraam et al. (2014) and Kind (2014) demonstrated the rationality of implementing flood protection policies by using cost–benefit analysis. Corderi-Novoa et al. (2021) and Yazdi et al. (2013) determine efficient flood protection policies using cost–benefit analysis.

There are some studies to determine efficient flood protection policies by using real option analysis. Kind et al. (2018) uses real option analysis to determine the efficient flood protection policy, and Abadie et al. (2017) applied real option analysis to Bilbao. Olsen et al. (2000) use the Markov decision process to determine efficient floodplain management.

In another analysis of flood policies from an economic perspective, Zhu and Lund (2009) derive efficient planning of the setback and the height of embankments. Kazama et al. (2009) evaluate the optimal dynamic policy of spatial flood protection for people living in the lower Mekong River region from the long-term viewpoint of economics. Morita (2008) presents a risk-analysis method for determining flood protection levels. Morita (2013) demonstrates methods for assessing a flood risk reduction achieved by a flood protection project and risks increased by climate change. In addition, Apel et al. (2008) propose a method to quantitatively evaluate the uncertainty arising from flood risks considering failures of the embankments. These above studies consider efficient embankment policies, but do not discuss the order of construction, the upstream section first or the downstream section first, at all. Simultaneously, these studies do not discuss fairness across residents in the upstream and downstream sections.

Only Mori & Takagi (2009) explore a method to determine which section of the river should be improved first, but this study does not determine the efficient level of embankments using a runoff model. Without runoff models, a physical flow relationship between the upstream and the downstream cannot be taken into account.

The purpose of the current study is to show the efficient embankment heights and the construction sequence according to the river flow and the situation along the river using cost–benefit analysis. For this purpose, inundation damage is formulated using a river model. From the several candidate models, including the storage function method, quasi-linear storage type, and storage function method, we adopt the kinematic wave model as the river model, because the kinematic wave method is based on rigorous physical dynamics.1 Next, to represent some realistic situation, we set the parameters of the model that match real rivers, and perform numerical simulations. Changing external parameters, we obtain important properties from the viewpoints of efficiency and fairness.

2 STUDY AREA: THE KITAKAMI RIVER AND THE ABUKUMA RIVER

The Kitakami River and the Abukuma River, located in Japan, are selected as case studies. The kinematic wave method is adopted because the river gradient is steep (more than 1/1000), as in most Japanese rivers. The Kitakami River, the longest river in the Tohoku region, with the largest basin area in the region, runs through Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures. The Abukuma River runs through Fukushima and Miyagi Prefectures. The population distribution of the upstream and downstream sections (in our model, we divide the river basin into two geographical sections: the upstream section and the downstream section) is calculated using ArcGIS. There are about 200,000 (180,000) households along the Kitakami (Abukuma) River. About 77.4% (69.4%) of the households are located in the upstream section and 22.6% (30.6%) are located in the downstream section along the Kitakami (Abukuma) River. Both rivers have a larger population in the upstream section than that in the downstream section.

Parameters regarding the river and the rainfall, such as river width, gradient, roughness and initial value of river depth, are shown in Table 1. Parameters regarding damage potential are shown in Table 2. The parameters in Tables 1 and 2 are set based on e-Stat. (n.d.), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Water Management and Land Conservation Bureau (2012a, 2012b, 2020), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (2012), and Past Weather Date Search Japan Meteorological Agency (2021).

| Kitakami River | Abukuma River | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Symbols | Tributaries | Upstream section | Downstream section | Upstream section | Downstream section |

| River width (m) | bx | 100 | 200 | 600 | 200 | 350 |

| River gradient | Ix | 1/100 | 1/500 | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | 1/1000 |

| Manning's roughness coefficient (m−1/3 × s) | nx | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Section length (m) | Δx | 50 × l03 | 100 × 103 | 100 × 103 | 80 × 103 | 80 × 103 |

| Time interval (s) | Δt | 3600 | 3600 | 3600 | 3600 | 3600 |

| The number of tributaries | M1, M2 | – | 3.6 | 6.45 | 5.0 | 4.4 |

| Water depth under normal conditions (m) | hs | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Height of embankment before improvement (m) | bs | – | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Duration of rainfall (hour) | τ | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Kitakami River | Abukuma River | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Symbols | Value or formula | Value or formula |

| Number of households (households) | N | 200 × 103 | 180 × 103 |

| Flood basin area (m2) | Ax | 650 × 106 | 300 × 106 |

| Building area per household (m2) | 100 × 106 | 920 × 106 | |

| Damage cost per square meter (Yen) | p(Hx) | 50,000 × Hx | |

| Construction cost of per-meter embankment (Yen) | C(bx) | ||

| Possible drainage volume per second (m3/s) | (A1 × rS=10)/(24 × 3600) | ||

| Discount rate | i | 0.02 | |

| Construction duration per section (years) | Tc | 15 | |

| Number of years to consider benefits from construction of embankments (years) | TB | 100 | |

3 MODEL

As mentioned above, we divide the river basin into two geographical sections: the upstream section (x = 1) and the downstream section (x = 2). The width, gradient, and roughness of the river vary according to the section. Embankments cannot be constructed simultaneously in the upstream section and the downstream section due to construction resource and fiscal constraints. Indeed, even within one section, construction takes a long time. For simplicity, we do not consider embankment collapses. In addition, the scale of rainfall is set to be equal regardless of the section.

3.1 Flood and inundation models

There are many hydrological models for different purposes (Jayawardena, 2014). Considering extreme flooding with heavy rainfall in Japan with the steep morphology of Japanese rivers, diffusion effects and sensitive processes can be neglected in water routing. Our geographical space is composed of the main river, tributaries and mountainous slopes simplified from the ordinary distributed hydrological model (e.g., Kazama et al., 2021). It rains all over the space. The rainfall on the mountainous slopes flows into the tributaries. The flow of the main river is expressed using the kinematic wave method.2

If a flood occurs, the depth of its section equals the height of the embankment. This is because the volume exceeding the possible volume that the main river can hold floods outside of the main river.

3.2 Damage cost and efficient construction condition

Using Equation (3), the cost of damage caused by flooding from the main river and rainfall on the flooded area can be defined. Here, note that damage cost is the function of the height of embankment in each section and rainfall of each recurrence interval . That is, the inundation depth is determined depending on the heights of embankments and rainfall. In addition, how many households live in each section also affects the damage cost. We define building area per household as , the number of households in the whole basin as and the ratio of households in each section to all households living along the main river as . Hereby, the possible area of building that could be inundated can be expressed as . By multiplying this area by the damage cost per unit of area depending on the inundation depth , we can formulate the damage cost in each section, . Here, flood damage basically depends on depth (inundation), velocity, and flood duration. However, the Japanese Flood Control Economy Manual calculates inundation damage based on inundation depth and inundation duration, and this method is the standard for embankment design in Japan. Therefore, we follow the method in the flood control economy manual (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Water Management and Land Conservation Bureau, 2020).5

Next, we define the efficient construction of embankments. This study assumes a situation where there is a natural levee before the levee is constructed. The most efficient embankment construction minimizes the total value of the expected damage cost in the whole basin and the construction cost of embankments. The expected damage cost and the construction cost of embankments depend on the heights of embankments. Here, we define this total value as the total expected social cost . This consists of three terms, as shown in Equation (6). The first term is the expected damage cost when construction in only one section of the two sections is completed. The second term is the expected damage cost when construction in both sections is completed. The third term is the construction cost of embankments. As mentioned previously, embankments cannot be constructed simultaneously in the upstream section and the downstream section, because, even within one section, construction takes a long time. So, by using dummy variable we consider from which section the construction starts. If the construction starts from the upstream section (called the upstream-section-first case, hereafter), is 1. On the other hand, if the construction starts from the downstream section (called the downstream-section-first case, hereafter), is 0. The construction duration per section is years and the last year for taking account of the benefit from construction of embankments is set at .

Here, note that is equal to because construction in the downstream section does not affect the damage cost in the upstream section. On the other hand, is not equal to because construction in the upstream section has an effect on the damage cost in the downstream section. In other words, as the embankment in the upstream section becomes higher, the damage cost in the downstream section becomes larger.

3.3 Setting parameters

To make our study realistic, we set the parameters to match the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers in Japan as closely as possible.

To estimate parameters , we use the data of daily maximum rainfall per year from the Japan Meteorological Agency. In estimating them, we follow “Technical Standards for River Erosion Control.”7 From this estimation, we obtain in the case of the Kitakami River, and in the case of the Abukuma River.

Next, we set the change in rainfall in a day. We target typhoons and torrential rains, which generally pass through a region in a relatively short time. The dynamic change in rainfall depends on the weather event. For example, some typhoons and torrential rains have early peaks, while others have later peaks. Furthermore, they can have several peaks. Among the various rainfall patterns, we assume the hourly distribution of the rainfall as a triangle with one peak in the middle. It can be said that this assumption is valid because this rainfall pattern represents the relatively average rainfall pattern among the possible typhoons and torrential rains. Under this assumption, the area of a triangle is equal to probabilistic precipitation at each recurrence interval .

Next, we set the discharge into each section on the basis of a planned flow distribution chart8 for the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers.

Currently, embankments are being constructed on the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers to prevent flooding against rainfall with the recurrence interval of 150 years, and the planned flow distribution chart represents the target discharge when this rainfall occurs. Therefore, we set parameters K and so that the peak discharge in each section when it rains with the recurrence interval of 150 years is equal to the discharge shown in the planned flow distribution chart.9

Regarding damage risk potential, we assume the damage cost per square meter as a linear function. This cost is set so as to follow the value shown in the “Flood Control Economy Manual” approximately. In this assumption, we approximate a step function of the damage cost with a linear function.10 So, as the inundation depth becomes higher, the damage cost increases. We assume that the construction cost of an embankment is a quadratic function of its height. This means the marginal cost of construction increases with the height. Next, possible drainage volume per day is set as . The reason for adopting is that sewerage improvement in Japan has been aimed to prevent inundation in possible flooded areas from rainfall with the recurrence interval of 10 years.

4 NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS FOR THE KITAKAMI AND ABUKUMA RIVERS

Using the parameters we set in Section 2, we perform numerical simulations for the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers. Using the results of the simulations, we explore the efficient construction sequence and the efficient heights of the embankments. We show the results of the numerical simulations for the Kitakami River and for the Abukuma River in this section.

Tables 3 and 4 show the total expected social costs depending on the construction sequence (the upstream-section-first case vs. the downstream-section-first case) and the differences between the total expected social costs in the two cases. As Tables 3 and 4 show, it is efficient to construct the embankments from the upstream section because the total expected social cost in the upstream-section-first case is lower than in the downstream-section-first case in both the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers. In the upstream-section-first case, the total expected social cost is 33.1 (170.8) billion yen smaller than that in the downstream-section-first case. The difference is equivalent to per-household gain of 230,000 yen (1.27 million yen) for households in the river basin of the Kitakami (Abukuma) river.

| Kitakami River | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The total expected social cost (trillion yen) | b1 | b2 | |||

| Upstream section first case | 0.99 | (1) | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| Downstream section first case | 1.02 | (2) | 3.6 | 3.6 | |

| Calculation formula | |||||

| Difference between the two cases | (2) − (1) | 33.1 billion yen | (3) | ||

| Per-household benefit | (3)/N | 230,000 yen | |||

| Abukuma River | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The total expected social cost (trillion yen) | b1 | b2 | |||

| Upstream section first case | 1.57 | (1) | 5.6 | 5.3 | |

| Downstream section first case | 1.74 | (2) | 5.6 | 5.2 | |

| Calculation formula | |||||

| Difference between the two cases | (2) − (1) | 170.8 billion yen | (3) | ||

| Per-household benefit | (3)/N | 1.27 million yen | |||

As for the efficient height of embankments, in the upstream-section-first case, the efficient height for the upstream section is 3.6 m (5.6 m) and that for the downstream section is 3.7 m (5.3 m). On the other hand, in the downstream-section-first case, the efficient height for the upstream section is 3.6 m (5.6 m) and that for the downstream section is 3.6 m (5.2 m) in the Kitakami (Abukuma) river. This implies that, in both the Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers, the efficient height of embankments in the downstream section in the upstream-section-first case is higher than that in the downstream-section-first case.

5 DISCUSSION

Efficient river protections depend on the spatial distribution of households. In addition, the efficient heights of the embankments depend on the condition of the main river and tributaries. In this section, we perform numerical simulations changing some parameters and explore the most efficient embankment heights and the most efficient starting section for construction depending on the conditions.

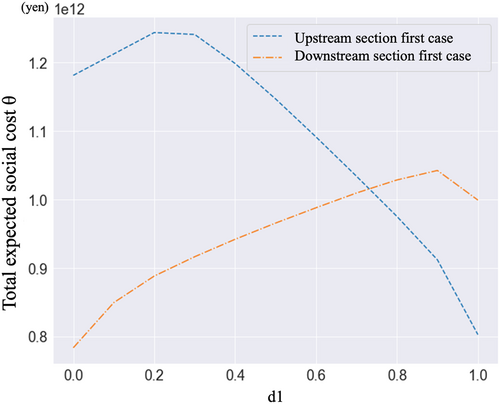

5.1 Efficient construction sequence depending on the population distribution ratio

We explore the efficiency of each construction sequence by considering the distribution of households in the basin for the case of the Kitakami River. Figure 2 shows the total expected social cost depending on which section construction starts from. The horizontal axis is the ratio of households in the upstream (i.e., the spatial distribution ratio of the population living in the upstream section) and the vertical axis is the total expected social cost depending on which section construction starts from. The blue dashed line indicates the total expected social cost in the upstream-section-first case, and the orange dashed-and-dotted line shows that in the downstream-section-first case.

When the ratio of households in the upstream section is small, the total expected social cost in the upstream-section-first case is larger than that in the downstream-section-first case. However, when the ratio of households in the upstream section is larger than a certain value, the opposite result arises. In our simulation, the shift occurs when is about 0.73–0.74.

The above discussion can be summarized as main finding 1.

Main finding 1

The upstream-section-first case can be efficient if the ratio of households in the upstream section to those in the downstream section is larger than a certain value (when is about 0.73–0.74).

In Japan, only from the viewpoint of fairness, the downstream-section-first case is adopted. Main finding 1 implies that when the population is large in the upstream section (when is about 0.73–0.74), from the viewpoint of efficiency, the upstream-section-first case should be adopted.

5.2 Comparison between the two construction sequence cases

Here, the expected damage cost in the downstream section is affected by the heights of embankments in the upstream section . The reason is the water depth in the upstream section, , is the function of the heights of embankments in the upstream section, , because when a flood occurs in the upstream section, the water depth in the upstream section at the next time point (i.e., time t + 1), , equals the height of the embankments, . So, the unit-width discharge into the downstream section , which is the function of , and the water depth in the downstream section is also the function of . Accordingly, the total flood water in the downstream section, , the damage cost in the downstream section, , and the expected damage cost are the functions of and . This influence of on expresses an externality in terms of economics. On the other hand, is the function of only .

These first-order conditions show that the marginal benefits and marginal construction costs are equal at the efficient embankment heights. Equations (10) and (11) imply the following proposition.

Proposition (optimal conditions for determining embankment heights)

- when the hydraulic model is a kinematic wave model, in determining the efficient embankment heights regardless of river conditions, the height of embankments in the upstream section must be decided based on the expected damage costs and , while the height of embankments in the downstream section is decided based on only the expected damage costs in the downstream section , and

- the heights of embankments and should be determined in consideration of their mutual interdependence, because the expected damage costs in the downstream section is a function of the heights of both embankment and embankment . In other words, determining the height of embankments in the upstream section affects the determination of the height of embankments in the downstream section . Determining the height of embankments in the downstream section also affects the determination of the height of embankments in the upstream section .

The proposition can be interpreted as follows. Because the construction of the upstream section increases the expected damage cost in the downstream section, , the efficient embankment heights in the upstream section should be lower compared with the heights without considering the increase in the expected damage cost in the downstream section. On the other hand, the construction of embankments in the downstream section does not affect the expected damage cost in the upstream section. So, the height of embankments in the downstream section can be determined based on only the benefit for their own section.

One important caveat is noted here. Our result that the construction of embankments in the downstream section does not affect the expected damage cost in the upstream section depends on our adopted hydraulic model, that is, kinematic model. The kinematic model can deliver the water level rise for only the downstream and does not influence the upstream. The calculation and conditions of the model depend on the steep morphology of Japanese rivers. If we consider the plain area like the downstream of rivers on the European continent, we need a different model like a dynamic wave model. In such a different hydraulic model, the loss of flood plain conveyance from construction of embankments may raise water levels in the upstream in contrast to our model.

To determine policies, efficiency and fairness are both important. As shown in Main finding 1, if the population in the upstream section is large, the upstream-section-first case is efficient. However, constructing embankments in the upstream section negatively affects the downstream section. This negative effect can cause some inequity problems. To consider both efficiency and fairness, some fairness policies additional to constructing embankments with efficient heights might be useful. An example of such policies is a subsidy from the upstream section to the downstream section.

5.3 Simulations with regard to number of tributaries and

River conditions as well as population distribution in the river basin have an effect on how river embankments should be developed and who benefits from the improvement. In this section, we use the Kitakami River setting as a basis for the simulation, and change the river conditions for the simulations. Among river conditions, we focus on the lateral flow, which is expressed as the number of tributaries, flowing into each section, and . Then, we explore the benefits when constructing embankments with efficient heights, using the efficient construction sequence, depending on how many tributaries each section has.

Table 5 shows the efficient construction sequence and the amount of benefit per household in the downstream section depending on the number of tributaries in each section. The values of M1 (3, 4, 5, 6, 7) and M2 (4, 5, 6, 7, 8) express the numbers of tributaries. The value in each cell in the table represents the benefit when the combination of the numbers of tributaries corresponding to the cell is set. The blue shaded cells in the table indicate that efficient construction is the upstream-section-first case and the green shaded cells indicate that it is the downstream-section-first case.

| Benefit for the downstream section per household (10,000 yen/household) | M2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| M1 | 3 | 89 | 260 | 469 | 1110 | 1471 |

| 4 | 31 | 196 | 408 | 654 | 1514 | |

| 5 | −43 | 113 | 330 | 572 | 1534 | |

| 6 | −132 | 19 | 237 | 486 | 735 | |

| 7 | −233 | −79 | 135 | 383 | 631 | |

-

Note:

: Upstream-section-first case.

: Upstream-section-first case.  : Downstream-section-first case.

: Downstream-section-first case.

Regarding the efficient sequence, we can see that if the number of tributaries in the upstream section is small while the number in the downstream section is large, the downstream-section-first case tends to be efficient.

Regarding the amount of benefit, as shown in Table 5, when the downstream-section-first case is efficient (i.e., when the combination of and as shown in the green shaded cells), as the number of tributaries in the upstream section is large and as the number of the tributaries in the downstream section is large, benefits for the downstream section tend to be large. On the other hand, when the upstream-section-first case is efficient (i.e., when the combination of and as shown in the blue shaded cells), as the number of tributaries in the upstream section is large and as the number of the tributaries in the downstream section is small, benefits for the downstream section tend to be small. Indeed, some cells show that the downstream section even suffers negative benefits (i.e., values shown in red).

The reason why these benefits can be negative is as follows. If the construction in the upstream section is completed, the water which used to flood outside of the main river before construction in the upstream section will flow into the main river in the downstream section. In addition, the discharge into the downstream section increases because flow velocity of the main river in the upstream section is larger due to a greater depth of the main river in the upstream section, which is caused by construction of the embankment. So, in the upstream-section-first case, the expected damage cost in the downstream increases for the first 15 years.11 When this damage cost exceeds the benefit after completing construction of embankments in the downstream section, the total benefit for the downstream section becomes negative.

These features are summarized below.

Main finding 2

Construction of embankments in the upstream section produces negative externalities in the downstream section, because it increases the possibility of flood in the downstream section. So, even if we construct embankments with efficient heights in both sections, residents in the downstream section can suffer negative benefits. But, when the amount of inflow from tributaries into the downstream section is sufficiently large compared to that into the upstream, embankments with efficient heights can give benefits to residents in the downstream section as well as the upstream section. In this case, the river protection achieves the Pareto improvement.

Main finding 2 implies that even if the upstream-section-first case is efficient, households in the downstream section can lose. So, they do not agree with the upstream section first policy. In this case, households in the upstream section should pay compensation to those in the downstream section in order for all the residents to have positive benefits. Note that when a policy achieves a higher efficiency than the current situation, an appropriate reallocation of incomes can increase the utilities of all the residents (i.e., the Pareto improvement is achieved).

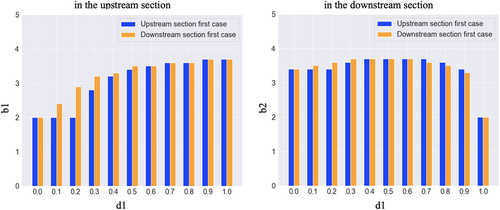

5.4 Difference in efficient heights between the two construction sequence cases

Finally, we explore the efficient embankment heights depending on which section the construction starts from, changing parameter , which is the ratio of the households in the upstream section to all households living in the whole basin.

Figure 3 shows the efficient embankment heights depending on the ratio of the households in the upstream section to all households living in the basin. The left side in the figure shows the efficient embankment heights in the upstream section, and the right one shows them in the downstream section. The horizontal axis is and the vertical axis is the efficient embankment heights depending on which section the construction starts from. The blue bars represent the efficient heights in the upstream-section-first case, and the orange bars represents those in the downstream-section-first case.

As shown in Figure 3, the efficient embankment heights depend on which section the construction starts from. For example, in the upstream section, when is from 0.1 to 0.5, the efficient embankment heights in the upstream section depend on from which section the construction starts. In the downstream section, when is from 0.1 to 0.3, and when is from 0.7 to 0.9, the efficient embankment heights in the downstream section depend on from which section the construction starts.

These differences in efficient embankment heights according to the construction sequence occur in the following two cases: (1) when the ratio of households living in the upstream section is small (except 0.0), and (2) when the ratio of households living in the upstream section is large (except 1.0).

First, when is from 0.1 to 0.5, the heights of embankments in the upstream section are higher in the case that the construction starts from the upstream section than in the downstream-section-first case. In addition, when ranges from 0.1 to 0.3, the heights of embankments in the downstream section are higher in the downstream-section-first case than in the upstream-section-first case. These features imply that if the population size in the downstream section is large compared with the upstream section, the heights of embankments in both sections can be higher in the downstream-section-first case.

This mechanism can be as follows. In the downstream-section-first case, the embankments in the downstream section have an ability to prevent flooding when the construction in the upstream section starts. So, the embankments in the upstream section can be built higher if the construction starts from the downstream section. Another reason is that the benefits for the downstream section arises for a longer period in the downstream-section-first case than the upstream-section-first case.

Next, we discuss the case when the ratio of households living in the upstream section is large. As shown on the right side of Figure 3, when is from 0.7 to 0.9, the heights of embankments in the upstream-section-first case are higher than in the downstream-section-first case. This is because when the construction in the downstream starts, the expected damage cost in the downstream section has become larger due to the construction in the upstream section. The heights of embankments in the downstream section are determined to prevent flooding from this time to the future. So, the downstream section needs higher embankments.

The difference in efficient heights between the two improvement sequence cases is summarized below.

Main finding 3

The efficient embankment heights can depend on which section the construction starts from:

Case 1. When the ratio of households living in the upstream section is small (except 0.0), the efficient embankment heights in the upstream section are higher in the downstream-section-first case than in the upstream-section-first case.

Case 2. When the ratio of households living in the upstream section is large (except 1.0), the efficient embankment heights in the downstream section are higher in the upstream-section-first case than in the downstream-section-first case.

The reason why and are excluded from Major finding 3 can be explained as follows. In , because there are no households living in the upstream section, constructing the embankments in the upstream section is not necessary. In , because there are no households living in the downstream section, constructing the embankments in the downstream section is not necessary.

Main finding 3 shows that depending on which section the construction starts from, the efficient embankment heights can be different. This implies that the construction sequence and the height of embankments should be determined simultaneously.

6 CONCLUSION

This study explores how tall the embankments should be constructed and which section the construction starts from depending on the population distribution and the river conditions to maximize the benefits. Then, we discuss the efficient construction of embankments from the two viewpoints of efficiency and fairness.

First, numerical simulations show that if the upstream section has a much larger population than the downstream section, the upstream-section-first case is efficient. Indeed, in the cases of the Kitakami River and the Abukuma River, the upstream-section-first case is efficient, and if the current downstream section-first, is changed to upstream section first, each household in the river basin gains 230,000 and 1.27 million yen, respectively. Second, the efficient construction sequence and the amount of benefit in the downstream section depend on the number of tributaries in each section. In the upstream-section-first case, the downstream section can lose. Finally, the simulations show that the efficient embankment heights can depend on from which section the construction starts.

For future research, our model does not consider the endogenous change in population distribution. In reality, the population allocation can change depending on how embankments are constructed. Indeed, many land use studies consider migration to explore the social welfare (e.g., Domon et al., 2022; Kono & Joshi, 2018; Kono & Joshi, 2019; Kono & Kawaguchi, 2017; Pines & Kono, 2012; Yoshida & Kono, 2020). Future studies should consider this endogenous migration. In addition, we can design some policies additional to constructing embankments in order to attain fairness among residents. For example, subsidies might be useful to mitigate fairness problems. We should examine what kind of subsidy is useful.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Government of Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 21K18128). Despite assistance from many sources, any errors in the paper remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

ENDNOTES

- 1 The kinematic wave method can be used when the river gradient is steep (more than 1/1000), as in most Japanese rivers. This is also shown in many Japanese hydrologic formula collections. The Kitakami and Abukuma Rivers targeted in this analysis also have river gradients steeper than 1/1000.

- 2 See Supporting Information S1 for the details on hydrological processes.

- 3 This drainage volume is determined by facilities for storage of rainwater, for example. In this study, we assume that water in residential areas accumulates in a stormwater storage facility, such as a rainwater storage pipe, and that its capacity is measured by the day.

- 4 Indeed, there are other water losses such as evaporation and deep infiltration. However, the runoff rate exceeds 95% during heavy rains. Therefore, losses such as evaporation and infiltration are not taken into account in this model.

- 5 There is a correlation between inundation depth and inundation duration, which is verified in Yamamoto et al. (2021).

- 6 Probabilistic precipitation indicates the amount of precipitation that is expected to occur once in a given recurrence interval.

- 7 See Supporting Information S2 for the estimation of parameters.

- 8 In Japan, a planned flow distribution chart indicates the maximum discharge in a main river and tributaries without flooding in the event of the target rainfall.

- 9 See Supporting Information S3 for the details on the setting of discharge.

- 10 In practice, the damage cost between inundation above floor level and below floor level differs significantly. However, we do not consider this distinction.

- 11 Here, “benefit” indicates the decrease in the expected damage cost due to the construction. So, if the expected damage cost increases, the benefit is negative.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.