Prevalence, comorbidities and mortality of generalized pustular psoriasis: A literature review

Abstract

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare auto-inflammatory skin disease characterised by acute episodes of sterile pustule formation. Diagnosis and treatment of the disease have historically been complicated by a lack of awareness, and no consistent global definition or clinical coding standards. Now acknowledged as a distinct clinical entity with a recognised genetic component, GPP can take a serious and life-threatening course due to systemic inflammatory complications and its association with various comorbidities. As with other rare diseases, there are significant challenges to understanding the epidemiology of GPP, notably a small patient population, non-standardised study methodologies and ethnic differences in its presentation. A clearer understanding of GPP is therefore required for clinicians to better manage patients with this rare condition. In this review article, we present an overview of the available data on GPP prevalence estimates in key demographics and report the frequency of genetic mutations associated with the disease. We detail the incidence of known comorbidities and summarise the data on mortality and assigned causes of death. Lastly, we discuss the various factors that impact the collection, interpretation and comparison of these data.

INTRODUCTION

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare, auto-inflammatory form of the skin disease psoriasis that places a significant burden on patients and is potentially life-threatening. It is characterised by recurrent episodes or flares of widespread cutaneous erythema with macroscopic sterile pustules.1, 2 Acute episodes of GPP are frequently associated with systemic symptoms, including high-grade fever, fatigue and leukocytosis.3-5 GPP can be further classified into acute GPP (von Zumbusch variant), pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (previously referred to as “impetigo herpetiformis”), annular pustular psoriasis and infantile/juvenile pustular psoriasis subtypes.1, 6 The clinical course of GPP is heterogeneous and covers a spectrum ranging from relapsing disease with recurrent flares occurring years after the initial diagnosis to a persistent disease continuously flaring over years. The severity of symptoms may also vary with each flare for an individual patient.7 Whilst often idiopathic in origin, a number of internal and external factors are linked to the initiation of GPP flares, including pregnancy or withdrawal of corticosteroids.5, 8 Bacterial and respiratory viral infections, including the SARS-CoV-2 virus, are also associated with triggering GPP flares across various clinical subtypes and genetic backgrounds.8-11

A high proportion of patients with GPP also present with pre-existing plaque psoriasis, and closely interlinked immunological pathways appear to underpin the pathogenesis of both conditions.8, 12 However, GPP has also been shown to present independently, and is now recognised as a separate clinical entity, with clear distinctions in genetic and immunologic determinants, and response to treatment.13-15 GPP is predominantly characterised by an abnormal innate immune response and is considered an auto-inflammatory disease; such diseases are defined as clinical disorders arising from genetic defect(s) leading to aberrant activation of the innate immune system and are characterised by continuous or recurrent episodes of inflammation with a potential secondary pathogenic involvement of the adaptive immune system.16, 17 In contrast, plaque psoriasis has both innate and adaptive immunopathogenic responses, and is considered an autoimmune condition.18, 19 Different cytokine pathways appear predominant in the manifestation of each disease, with the interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 axis seeming to underpin plaque psoriasis,20 while the IL-36 pathway drives GPP pathogenesis.18, 21

The role of the IL-36 pathway was initially identified following the discovery of loss-of-function mutations in IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36Ra), encoded by the IL36RN gene.11, 14 A growing body of evidence now indicates that dysregulation of the IL-36 cytokine signalling pathway is central to the development of GPP, wherein uncontrolled expression and activation of IL-36 cytokines lead to the activation of clonal T-cell responses and neutrophil recruitment in the epidermis with associated pustule formation.18, 22 Indeed, blocking IL-36 signalling can efficiently control GPP flares.23 The significant role of the IL-36 pathway is further supported by histological analyses.18 IL36RN mutations are associated with a severe form of GPP, characterised by early onset, more systemic inflammation, lack of associated plaque psoriasis and dependence on systemic therapy.15, 24, 25

Immunomodulatory therapies, such as oral retinoids, cyclosporin and methotrexate, are often used as first-line treatment for GPP; however, their use is based upon current treatments for plaque psoriasis, with limited GPP-specific evidence, and no randomised controlled trial data available.3, 26 While specific guidelines exist for GPP in some countries,26 there is no globally accepted guidance in place for acute management of GPP flares, nor for long-term treatment of the disease. To date, biologics have been approved for the treatment of GPP in some countries; in Japan, the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-blocking agents, adalimumab, infliximab and certolizumab pegol; the monoclonal antibodies that antagonise IL-17/IL-17R, secukinumab, brodalumab and ixekizumab; and the IL-23 inhibitors, risankizumab and guselkumab, are approved.5, 26 However, no GPP-specific therapeutic agents are approved in the USA or Europe.5, 27 The urgent need for well-designed trials to provide clinical evidence on the safety and efficacy of targeted therapies specific for GPP is hindered by the rarity of cases and the relapsing–remitting nature of the disease.

Here, we conduct a literature review to identify studies providing estimates of mortality, prevalence and comorbidities in the GPP population, in addition to detailing the prevalence of specific mutations associated with the disease. We discuss the various factors that impact data collection and the potential limitations in the effective interpretation and comparison of study data in these areas. The literature search was conducted in Embase, Medline and the Cochrane Library in April 2021 and supplemented by a bibliographic review of relevant literature reviews and consensus studies identified in the electronic searches until October 2021; a congress abstract search was also conducted.

GPP PREVALENCE

GPP prevalence in the general population

Generalized pustular psoriasis prevalence estimates in the general population vary considerably, between 1.76 and 124 patients per million persons.28-30 A retrospective epidemiological survey that collected in- and outpatient data on 99 patients from 121 dermatological wards throughout France in 2004 reported a prevalence of 1.76 patients per million persons.28 A second study, by Lee et al.,29 collected data from the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database between 2011 and 2015. Annual GPP prevalence estimates were calculated from GPP prevalence in patients with psoriasis and psoriasis prevalence data in the general population; GPP prevalence in the general population was between 88 and 124 patients per million persons per year.29 Prevalence data in a third study was obtained via questionnaires sent to 575 community centre hospitals throughout Japan, seeking details of visiting patients with GPP during 1983–1989.30 This study included 541 patients with GPP and reported a GPP prevalence of 7.46 patients per million persons, with 2.87 patients per million persons presenting with acute GPP.30 Considering the potential bias introduced by hospital-only questionnaires, the Korean study, with a comprehensive national database as a data source and a high number of included patients, is perhaps the most reliable source.29 While these data indicate the prevalence of GPP in East Asian countries may be higher, given the small number of studies and varying types of data source, we are unable to confirm this conclusion.

GPP prevalence in patients with psoriasis

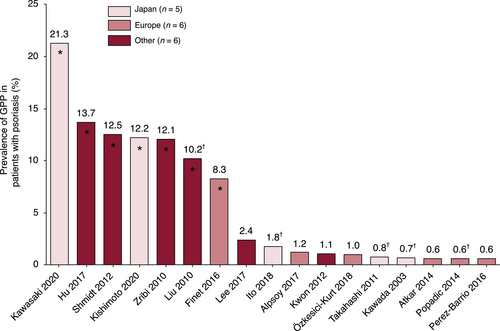

Estimates of GPP prevalence among patients with psoriasis range between 0.6% and 2.4% (Figure 1, Table S1).29, 31-46 Although there are some reports of higher rates, up to 21.3%, these studies could be considered potentially heterogeneous because of their inclusion of only hospitalised patients, those with psoriasis subtypes or those treated with specific drugs.31-36, 45

Three of the five Japanese studies with similar prevalence utilised information from the Japanese Society for Psoriasis Research database.37, 39, 41 Similarly, a European study with a higher prevalence than other reports from this region was exclusive to patients admitted to hospitals for severe psoriasis.35 Of the remaining studies from outside Japan or Europe, the studies with the highest percentages included either hospitalised patients31, 32, 34 or patients undergoing TNF-α inhibitor therapy.33 The final two studies included data either from a national database or from study centres/clinics and reported a lower range of 1.1%–2.4%.29, 40

Overall, these data indicate that GPP is a rare disease, with a consistently low prevalence in both the general population and patients with psoriasis.

GPP relapse rates and number of flares

The relapse rate in patients with GPP varies considerably, from 32.3% to 61.4% (Table 1),8, 25, 28, 44, 47-54 even when discounting a study of three patients that showed a relapse rate of 100%.53 This can potentially be attributed to different patient population characteristics and reported GPP variants across these studies. There was also a considerable disparity in relapse definition, which included hospital readmission, resistance to treatment or relapse due to cessation of treatment or infection (Table 1). In a retrospective study of 95 patients with acute GPP, 54 patients had only one flare (56.8%), 28 had two to five flares (29.5%) and 13 had more than five flares (13.7%) over a mean follow-up of 5 years.8 Recent data from a survey of Corrona registry dermatologists in the USA, covering GPP diagnosis, symptoms and treatment, reported that most dermatologists (69%) estimate their patients have an average of no or one GPP flare per year, with an average of two or three flares per year reported by 28%.55

| Year | Country | Subgroup/ clinical trial arm | Time points | Relapse definition (e.g. relapse rate over 1 year) | Total patients with GPP, N | Relapsing patients with GPP, n (%) | Additional details | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | France | Dermatological wards (GPP) | 1 year; all in- and outpatients who visited the department in 2004 for GPP | Recalcitrant GPP | 99 | 42 (42.4) | [28] | |

| 2011 | Portugal | Acute GPP | 1973–2008 | Patients readmitted for acute GPP before the end of 2008 | 34 | 11 (32.3) | 6% (2/34) were readmitted for dissemination of psoriasis vulgaris | [47] |

| 2014 | Malaysia | Acute GPP | Patients diagnosed between 1989 and November 2011 | Number of pustular flares corresponding to >30% of body surface area | 95 | 41 (43.2) | 28 patients had two to five flares and 13 had more than five flares over a mean follow-up of 5 years | [8] |

| 2014 | Serbia | Patients with GPP | 20 years (1992–2011) | Patients with GPP (initial presentation) having GPP relapse (secondary presentation) | 5 | 2 (40.0) | Patients with PP (initial presentation) having GPP relapse (secondary presentation): 3 | [44] |

| 2015 | South Korea | All included patients (acute GPP, GPP of pregnancy, juvenile GPP, annular GPP) | 11 years (2002–2012) | Persistence/relapse: cases in which GPP was persistent or relapsed within 1 year | 25 | 19 (76.0) | Persistence/relapse also stratified by previous history of PP and split into type of skin lesion that occurred during persistence/relapse | [48] |

| 2017 | China | Paediatric-onset GPP | January 2013 to July 2014 | Relapse by April 2015 | 66 | 50 (NR) | All the patients presented GPP pattern at the first episode | [51] |

| 2017 | China | All included patients (GPP and PPP) | NR | NR (see details) | 15 | 1 (NR) | 16 achieved a complete recovery after the first round of acitretin therapy, with a catabasis ranging from 1.5 to 4 years; the other 50 cases all suffered from recurrent episodes of the disease so that periodic prescription of acitretin was necessary. Among the 50 inpatients, the duration of remission ranged from 6 months to 4 years | [50] |

| 2017 | Malaysia | Acute GPP | 6 months | >1 pustular episode | 21 | 14 (66.7) | [25] | |

| Malaysia | Included all variants of GPP | 6 months | >1 pustular episode | 27 | 14 (51.8) | |||

| 2018 | Japan | Patients with GPP | 52 weeks | NR | 10 | 0 (NR) | There was no new occurrence of psoriasis observed in any patient through week 52, although one patient with GPP experienced worsening of psoriasis with mild severity on day 3 after the first dose administration | [52] |

| 2019 | Tunisia | Patients with GPP | 31 years (1987–2018) | Relapse definition not provided but noted when treatment stopped | 44 | NR (61.4) | [54] | |

| Tunisia | Patients with GPP | 7 years (2012–2018) | Relapse definition not provided but noted when infection occurs | 17 | NR (35.3) | Relapses when infection occurred: 17.6% | ||

| 2019 | Tunisia | GPP of pregnancy | 2008–2017 | NR | 3 | 3 (100.0) | Relapse during pregnancy | [53] |

| 2021 | Germany | All patients (including von Zumbusch and annular subtypes) | January 2005 to May 2019 | Course of disease: predominantly relapsing | 86 | 46 (54.1) | Course of disease: persistent and relapsing also reported (7.0, 8.2%) | [49] |

- Note: The studies are presented by year.

- Abbreviations: GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; NR, not reported; PP, plaque psoriasis; PPP, palmoplantar pustulosis.

Prevalence of genetic mutations associated with GPP

Understanding the overall prevalence of specific genetic mutations in individuals with GPP is hindered by the fact that most reports have assessed only a limited number of genetic loci, in relatively small populations. Several studies have reported on the prevalence of specific mutations in genes associated with the IL-36 inflammatory cascade in patients with GPP, with a small number of these examining family history of psoriasis (Table 2).11-15, 24, 56-66 Mutations in IL36RN induce a loss of function in IL-36Ra, leading to an amplification of downstream inflammatory responses.67 Many of these mutations appear exclusive to specific ethnic populations or geographical regions, such as the homozygous missense mutation L27P originally identified by Marrakchi et al.11 in Tunisian families (Table 2). Specific alterations in the IL36RN gene have also been associated with an earlier age of onset and a more severe form of GPP.12, 24 In addition, a study in a Chinese familial cohort has linked the prevalence of IL36RN mutations to patients presenting with geographic tongue.66

| Year | Gene of interest | Study design and population | Prevalence of mutation or allelic variation in study population | Additional details | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | IL36RN | Homozygosity mapping and direct sequencing of the IL36RN gene in nine Tunisian multiplex families with autosomal recessive GPP | A homozygous missense mutation in IL36RN was identified in all GPP cases (n = 16) with a carrier prevalence of approximately 1% and an allele prevalence of 0.5% in this population | Authors identified significant linkage to an interval on chromosome 2q13-q14.1 and a homozygous missense mutation in IL36RN in all familial cases of GPP (p.LeuL27Pro) | [11] |

| 2011 | IL36RN | Five unrelated individuals of European descent with GPP were screened for mutations in IL36RN | Three of the five individuals (60%) presented one or two mutations in IL36RN | A homozygous c.338C>T (p.Ser113Leu) missense substitution of IL36RN was identified in two individuals. In a third subject, a compound heterozygote for c.338C>T (p.Ser113Leu) and a c.142C>T (p.Arg48Trp) missense substitution was identified | [14] |

| 2012 | CARD14 | Two families, one of European and one of Taiwanese ancestry with multiple cases of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, were screened for mutations in the CARD14 gene | Identified mutations in CARD14 were shown to be present in the psoriatic population at very low frequencies (<0.1% of cases) | Authors identified separate gain of function mutations c.349G>A (p.Gly117Ser) (in the family of European descent) and c.349þ5G>A (in the Taiwanese family) | [56] |

| 2013 | IL36RN | Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in 14 Japanese patients with GPP | Two of the 14 patients with GPP (14.2%) presented separate mutations in the IL36RN gene | One patient was compound heterozygous for mutations c.115+6T>C and c.368C>G (p.Thr123Arg), whereas the other carried compound heterozygous mutations c.28C>T (p.Arg10*) and c.115+6T>C in the IL36RN gene | [57] |

| 2013 | IL36RN | Authors sequenced four IL36RN coding exons in 84 patients with GPP from three cohorts (European, Asian: Malay, Asian: Chinese) | Homozygous/compound heterozygous alleles in IL36RN were observed in 7/84 (8.3%) GPP cases | The most prevalent allele in the European population, the p.Ser113Leu substitution, was found in all three cohorts. The most frequent change in the Asian dataset was the c.115b6T4C variant | [13] |

| 2013 | IL36RN | Authors screened for IL36RN mutations in two groups of Japanese patients with GPP: GPP without PP (n = 11) and GPP with PP (n = 20) | 9/11 cases of GPP alone (81.8%) had homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in IL36RN, while 2/20 cases of GPP with PP (10%) had compound heterozygous mutations in IL36RN | Three IL36RN mutations were reported: c.28C>T homo, c.28C>T homo and c.28C>T hetero | [15] |

| 2015 | IL36RN | A cross-sectional study investigating the risk factors predicting IL36RN mutation in 57 Chinese patients with different clinical features of pustular psoriasis, including 32 with GPP | Patients with GPP exhibited the highest IL36RN mutation rate (75.0%) | The GPP subgroup consisting of patients who had features of ACH exhibited the highest c.115+6T>C IL36RN mutation rate (93.8%) | [58] |

| 2015 | IL36RN | Case versus control study in the frequency of heterozygous IL36RN alleles in British (n = 22), Chinese (n = 72), Japanese (n = 66) and Malay (n = 110) adults with GPP, versus controls (n = 1332) | Heterozygous IL36RN alleles were observed in 9.1% (British), 5.6% (Chinese), 4.5% (Japanese) and 4.5% (Malay) of GPP cases | Significant associations in the frequency of heterozygous IL36RN alleles were seen in patients with GPP in two of the four populations (Japanese [p = 0.019, OR 19.7], Malay [p = 0.006, OR 20.1]) | [24] |

| 2015 | CARD14 | Sequencing of CARD14 coding sequences in patients with GPP versus controls in Chinese (GPP, n = 48; control, n = 400) and Japanese (GPP, n = 42; control, n = 844) populations | The p.Asp176His variant of CARD14 was more common in cases versus controls in Chinese (6.2% vs. 1.0%; p = 0.03) and Japanese (9.5% vs. 1.7%; p = 0.008) populations | Overall, the p.Asp176His variant of CARD14 showed a significant association with GPP in Asian populations (p = 8.4 × 10−5; OR 6.4) | [59] |

| 2016 | IL36RN | Sequencing of the IL36RN gene in patients with GPP (n = 14) from three Algerian families. Assessed a range of IL36RN mutations on IL-36Ra protein expression in functional assays | Authors identified two novel IL36RN homozygous mutations in Algerian patients with familial generalized pustular psoriasis | Two novel variants were c.41C>A/p. Ser14X and c.420_426del/p. Gly141MetfsX29, both of which led to enhanced production of IL-8. Functional assays revealed null mutations in IL36RN were unable to repress IL-36-dependent activation of NF-κB pathways and were associated with severe clinical phenotypes including GPP and AGEP | [65] |

| 2016 | IL36RN, AP1S3 | Screening for mutations in the IL36RN and AP1S3 genes in two individuals of European heritage with GPP | NR | Authors identified specific mutations in IL36RN (p.Ser113Leu/–) and AP1S3 (p.Phe4Cys/–) in two of three patients | [60] |

| 2018 | IL36RN | A case–control study in Han Chinese individuals screening for mutations in the IL36RN gene (GPP, n = 43; control: n = 50) | Three IL36RN variants were detected in 26/43 patients with GPP (60.5%), with none of the same mutations found in controls | Among the three variants identified, c.115+6T>C (p.Arg10ArgfsX1, rs148755083), c.140A>G (p.Asn47Ser, rs28938777) and c.227C>T (p.Pro76Leu, rs139497891), c.115+6T>C was the most common, with a variant frequency of 55.81% | [66] |

| 2018 | IL36RN, CARD14, AP1S3 | Previously identified mutations in IL36RN, CARD14 and AP1S3 genes were sequenced in 61 patients with GPP (European, n = 51; other, n = 10) | 36% of patients with GPP carried a rare variant in at least one of the three genes. Biallelic and monoallelic IL36RN mutations were identified in 15 and five patients with GPP, respectively |

Selected variant details from 51 European patients: AP1S3: c.11T>G (p.Phe4Cys): 1% of patients with GPP; c.97C>T (p.Arg33Trp): 1% of patients with GPP CARD14: c.206G>A (p.Arg69Gln): 1% of patients with GPP c.349G>A (p.Gly117Ser): 1% of patients with GPP; 536G>A (p.Arg179His): 1% of patients with GPP IL36RN: mutant alleles: 24.5% of patients with GPP |

[62] |

| 2019 | IL36RN, AP1S3, CARD14 | Screening of IL36RN and AP1S3 genes in eight unrelated patient cohorts of pustular psoriasis (GPP, n = 251; PPP, n = 560; ACH, n = 28; and multiple diagnoses, n = 24). Mutation screening was carried out in 473 cases | AP1S3 alleles had a similar frequency (3%–5%) across all disease subtypes; IL36RN mutations were observed with greater frequency in GPP (23.7%) compared with PPP (5.2%) cases | Mutations in IL36RN were less common in patients with PPP than in those with GPP (19%; p = 1.9 × 10−14). IL36RN disease alleles were also found to have a dose-dependent effect on age of onset in all forms of pustular psoriasis (p = 0.003). CARD14 mutations were observed in a small minority of cases | [12] |

| 2020 | SERPINA3 | Whole-genome sequencing of the SERPINA3 gene in 25 patients with GPP | 8% of patients with GPP presented with a specific deletion in the SERPINA3 gene | Authors identified a heterozygous deletion c.966delTp.Tyr322Ter of SERPINA3 in patients with GPP (p = 2.65 × 10−4; OR 207) | [63] |

| 2020 | MPO | Whole-exome sequencing of MPO in unrelated patients with GPP (n = 19) versus controls (n = 56,746) | The frequency of an MPO variant was observed in 5.3% (1/19) of GPP cases compared with 0.003% (2/56,746) in controls (p = 0.001) | Authors identified a homozygous splice-site mutation (c.2031–2A>C) in MPO associated with GPP | [64] |

| 2021 | IL36RN | Screening for mutations in the IL36RN gene in a single patient with paediatric-onset GPP | NR | Authors identified two mutations (one novel) in an 11-year-old female patient with GPP; one was a previously unreported novel variant of c.59A>G in exon 3, and the other a previously reported variant of c.115+6T>C in intron 3 | [61] |

- Note: The studies are presented by year.

- Abbreviations: ACH, acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; IL, interleukin; IL-36Ra, IL-36 receptor antagonist; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; PP, plaque psoriasis; PPP, palmoplantar pustulosis.

Genetic mutations in additional components of the IL-36 signalling pathway have also been associated with the development of GPP in different patient groups; mutations in CARD14, which facilitates the activation of proinflammatory transcription factors in keratinocytes, are linked to GPP in Asian populations.56, 59, 62 Mutations in AP1S3, which encodes a protein implicated in autophagosome formation, are also associated with GPP.12, 60, 62 Some patients with GPP display a loss-of-function mutation in the serine protease inhibitor, SERPINA3. The resulting lack of inhibition of neutrophil serine proteases, such as cathepsin G, increases activation of IL-36β, promoting inflammation.63 Lastly, loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding myeloperoxidase, MPO, which encodes an essential component of neutrophil granules, have recently been identified in patients with GPP.64

Almost 50% of patients with GPP have been shown to carry a variant in one or more genes that are associated with the disease, demonstrating a genetic component to pustular forms of psoriasis.68 In individuals with GPP that has a recognised genetic component, mutations in IL36RN appear to be the main predisposing factor.11-13, 15, 24, 57, 60-62 Further studies are required to identify any additional, as-yet-unknown genes, as well as more accurately define the pathogenic contribution of genetic- and ethnic-specific variations. Overall, the prevalence of IL36RN mutations in patients with GPP ranged from between 10% and 82%,18, 58 with biallelic IL36RN mutations identified as causal or predisposing in 21%–41% of cases.11, 14, 15, 24, 62

COMORBIDITIES OF GPP

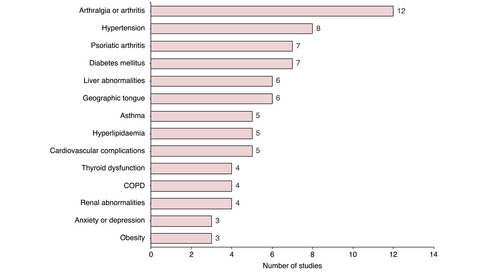

Reported comorbidities in patients with GPP are shown in Figure 2. Twelve studies reported arthralgia or arthritis (median 16.7%), with psoriatic arthritis also reported from seven studies in a lower percentage of patients (median 7.8%). The geographic tongue was reported at an increased rate in Asian studies (four studies compared with two non-Asian studies), and Asian studies reported a higher average percentage of patients with GPP with geographic tongue (14.3%, 38.5%, 61.9% and 83.9%)25, 66, 69, 70 compared with the German and American studies (22.0% and 17.0%, respectively).6, 62 It should be noted that this observation is limited by the small number of studies. Additional comorbidities, including renal abnormalities,31, 49, 71, 72 anxiety and depression,49, 72, 73 cardiovascular complications,8, 47, 49, 71, 72, 74 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease49, 72, 75, 76 and obesity8, 74, 75 were reported in fewer than five studies. Eight studies had a sample size of fewer than 12 patients with GPP,44, 52, 53, 69, 71, 77-79 while four studies included only paediatric cases of GPP,44, 51, 53, 70 which may affect the generalisability of their comorbidity estimates.

In accordance with previously published data,8, 12 our search identified twenty studies that reported a high proportion of patients with GPP that also presented with plaque psoriasis (median 46.4%, range 15.4%–83.0%). It should be highlighted that many of the comorbidities identified here are prevalent in both conditions; including hypertension, psoriatic arthritis, diabetes and cardiovascular complications.80 This overlap in comorbidity presentation is perhaps unsurprising given the closely interlinked inflammatory pathways that appear to drive the pathogenesis of both conditions.81 It is therefore comorbidities characterised by direct organ attacks from neutrophilic features of the auto-inflammatory process that might be expected to specifically characterise GPP. Three studies identified here present cases of sepsis in hospitalised patients with GPP,70, 72, 74 and sepsis or septic shock directly related to GPP represents the most common cause of mortality identified in our literature search. Several case reports have reported neutrophilic cholangitis as a comorbidity of GPP,82, 83 and in the study by Viguier et al.84 neutrophilic cholangitis was identified in two patients who underwent a biopsy following pronounced liver test abnormalities. Acute respiratory distress syndrome has also been identified as an extracutaneous comorbidity of GPP.5, 26

Comorbidities of GPP in Japanese studies

Eight studies were conducted in Japan (Table 3),30, 52, 71, 74, 75, 77-79 with five reporting a sample size of fewer than 12 patients, which could suggest that their comorbidity estimates may not be representative of the general GPP population. Those studies reporting a larger number of participants with GPP30, 74, 75 are therefore assumed to be more representative of the wider population. Arthralgia or arthritis was the most commonly reported comorbidity in Japanese studies, observed in four reports and ranging from 8.3% to 50.0% of GPP cases.52, 77-79 Three studies reported diabetes mellitus in 10.0%–22.8% of patients with GPP.71, 74, 79

| Year | Time points and study details | N | Arthralgia or arthritis, % (n) | Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | Hypertension, % (n) | Hyperlipidaemia, % (n) | Psoriatic arthritis, % (n) | Geographic tongue, % | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Patient visits 1983–1989 | 208 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [30] |

| 2014 | NR | 8 | 50.0 (4) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [77] |

| 2016 | Phase III, open-label interventional, multicentre, single arm, study carried out 2013–2016 | 12 | 16.7 (2) | 16.7 (2) | 8.3 (1) | NR | NR | NR | [79] |

| 2017 | Phase III, open-label multicentre study carried out 2013–2014 | 12 | 8.3 (1) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [78] |

| 2018 | Phase III, multicentre, open-label, 52-week study carried out 2015–2016 | 10 | NR | 10.0 (1) | 10.0 (1) | 10.0 (1) | NR | NR | [71] |

| 2018 | Phase III, multicentre, open-label, 52-week study carried out 2015–2017 | 10 | 10.0 (1) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [52] |

| 2021 | Patient data from the JMDC database from January 2015 to December 2019 | 110 | NR | NR | 23.6 | 10.0 | 16.4 | NR | [74] |

| 2021 | Hospital administrative claims database of patients hospitalised between July 2010 and March 2019 | 1516 | NR | 22.8 (346) | 22.6 (343) | NRa | NR | NR | [75] |

- Note: Studies are presented by year.

- Abbreviations: GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; JMDC, Japanese Medical Data Centre; NR, not reported.

- a Dyslipidaemia was reported in 77 patients.

Comorbidities of GPP in European studies

Comorbidities were presented in seven European studies (Table 4).44, 47, 49, 62, 84-86 Two studies reported arthralgia or arthritis in 8.8%–13.6% of patients with GPP,47, 84 and two additional studies stated that psoriatic arthritis was present in up to 29.5% of cases.49, 62

| Year | Country and time point | N | Arthralgia or arthritis, % (n) | Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | Hypertension, % (n) | Hyperlipidaemia, % (n) | Psoriatic arthritis, % (n) | Geographic tongue, % (n) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | UK; clinician-obtained patient data collected 1968–1971 | 106 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [85] |

| 1985 | Poland; patients with GPP treated with etretinate 1979–1984 | 18a | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [86] |

| 2004 | France; patients hospitalised for a GPP flare between 1995–2001 | 21 | 14.3 (3) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [84] |

| 2011 | Portugal; retrospective analysis of clinical data collected 1973–2008 | 34a | 8.8 (3)a | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [47] |

| 2014 | Serbia; medical records of children (<16 years) followed 1992–2011 | 8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | [44] |

| 2018 | Germany; three patient cohorts | 61 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 29.5 (18) | 22.0 (13.0) | [62] |

| 2021 | Germany; patients treated in five University medical centres January 2005–May 2019 | 86b | NR | 12.8 (11) | 41.9 (36) | NRc | 17.4 (15) | NR | [49] |

- Note: Studies are presented by year.

- Abbreviations: GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; NR, not reported.

- a Comorbidity measured in patients with acute GPP.

- b N also includes 16 patients with annular GPP.

- c Dyslipidaemia was reported in six patients.

Comorbidities of GPP in countries outside Europe or Japan

Fourteen studies assessing comorbidities of GPP were conducted in countries outside of Europe and Japan, including China, USA, Malaysia and Tunisia (Table 5).6, 8, 12, 25, 48, 51, 53, 54, 66, 69, 70, 72, 73, 87 Three studies were conducted in patients with juvenile GPP, which may have affected comorbidity rates51, 53, 70 as conditions such as hyperlipidaemia and type 2 diabetes are less prevalent in children.

| Year | Country and time point | N | Arthralgia or arthritis, % (n) | Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | Hypertension, % (n) | Hyperlipidaemia, % (n) | Psoriatic arthritis, % (n) | Geographic tongue, % (n) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | USA; medical records of patients hospitalised 1961–1989 | 35a | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 17.0 (NR)a | [6] |

| 1994 | China; hospital medical records of in- and outpatient data collected 1982–1992 | 78 | NR | NR | NR | 7.7 (6) | NR | NR | [87] |

| 1997 | Singapore; medical records of patients with pustular psoriasis at a tertiary referral skin centre 1989–1993 | 7a | NR | NR | NR | NR | 28.6 (2)a | 14.3 (1)a | [69] |

| 2014 | Malaysia; medical records from a single dermatology centre 2001–2010 | 101; 95a | 34.7 (35); 36.8 (35)a | 23.8 (24) | 25.7 (26) | 25.7 (26) | NR | NR | [8] |

| 2015 | South Korea; medical records from visiting patients at two tertiary hospitals January 2002–December 2012 | 33; 21a | 15.2 (5); 23.8 (5)a | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [48] |

| 2017 | China; three family cohorts | 56 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 83.9 (47) | [18] |

| 2017 | China; inpatient medical records of children <14 years from a single dermatology department, January 2005–December 2014 | 26a | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3.9 (1)a | 38.5 (10)a | [70] |

| 2017 | China; inpatient records of children (<18 years) admitted to a single dermatology department January 2013–July 2014 | 66 | 100.0 (66) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [51] |

| 2017 | Malaysia; medical records of a single dermatology centre November 2015–April 2016 | 27; 21a | 22.2 (NR); 23.8 (5)a | NR | NR | NR | NR | 61.9 (13)a | [25] |

| 2019 | International; data from eight patient cohorts | 251 | NR | 14.4 (13)b | 15.6 (14) | NR | NR | NR | [12] |

| 2019 | Tunisia; retrospective analysis of clinical data collected 1987–2018 | 44 | 15.9 (7) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [54] |

| 2019 | Tunisia; retrospective analysis of clinical data 2008–2017 | 3c | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [53] |

| 2020 | USA; administrative claims database records of in- and outpatient data collected October 2015–March 2019 | 1669 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.8 (NR) | NR | [73] |

| 2021 | USA; electronic medical records analysis of data collected July 2015–July 2017 | 71d | 13 | 28 | 30 | NR | 7 | NR | [72] |

- Note: Studies are presented by year.

- Abbreviations: GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; NR, not reported.

- a Comorbidity measured in patients with acute GPP.

- b N = 90.

- c Female patients with GPP of pregnancy.

- d GPP-related hospitalization visits.

GPP MORTALITY

GPP mortality rates

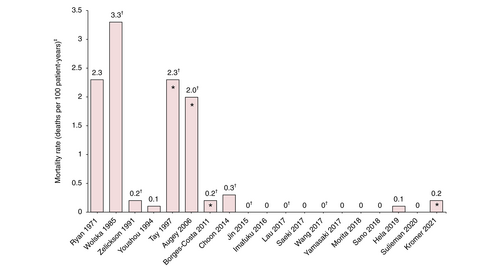

Generalized pustular psoriasis mortality rates varied considerably, from 0 to 3.3 deaths per 100 patient-years across studies that reported at least one death (Figure 3).6, 8, 25, 28, 47-49, 52, 69-71, 78, 79, 85-89 European studies presented the highest mortality rates: three studies presented mortality rates greater or equal to two deaths per 100 patient-years,28, 85, 86 while Asian studies had the lowest rates with most reporting a rate of 0.5 or less (Figure 3).8, 48, 52, 70, 71, 78, 79, 87-89 Mortality rates were generally lower in more recently published studies versus older studies; the average mortality rate for studies published prior to 2000 was 1.6 deaths per 100 patient-years, compared with 0.2 deaths per 100 patient-years in those published after 2000 (Figure 3). A study from 2021 reported a 4.3% mortality rate in patients with GPP who required hospitalization, with no data on deaths per 100 patient-years available.74

Causes of mortality

Most studies with at least one occurrence of death linked to GPP provided the cause (Table 6),6, 8, 25, 28, 47-49, 52, 54, 62, 69-72, 78, 79, 85-90 the most common were sepsis or septic shock and cardiovascular complications. A limited number of studies provided details on treatment-related causes of death; the study by Ryan and Baker in 1971 included deaths clearly attributable to therapy and deaths to which steroid and methotrexate may have contributed,85 while the report by Mössner et al.62 detailed an unconfirmed potentially treatment-related death. A 2021 study was able to provide more details on treatment-related deaths; patients who received biologics were younger, had fewer comorbidities, and had a significantly lower in-hospital mortality rate (1.0%) compared with patients receiving oral agents (3.7%) or corticosteroids only (9.1%, p < 0.001).74

| Year | Country | Total patients (N) | Patients with GPP (N) | Deaths in patients with GPP n (%) | Sepsis or septic shock directly related to GPP, n (%) | Cardiovascular complications directly related to GPP, n (%)g | Cause directly related to disease, n (%) | Treatment related, n (%) | Cause not reported, n (%) | Other, n (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | UK | 155a | 106 | 34 (32.1) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 8 (23.5)a | 18 (52.9)a | 8 (23.5) | 0 (0.0) | [85] |

| 1985 | Poland | 18 | 18 | 3 (16.7) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.1) | [86] |

| 1991 | France | 992b | NR | 18 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 18 (NR) | NR | [90] |

| 1991 | USA | 63 | 35 | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | [6] |

| 1994 | China | 90 | 78 | 1 (1.3) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | [87] |

| 1997 | Singapore | 28 | 11 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [69] |

| 2006 | France | NRc | 99 | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [28] |

| 2011 | Portugal | 47d | 34 | 2 (6.0) | 2 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [47] |

| 2014 | Malaysia | 102 | 95 | 7 (7.4) | 4 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | [8] |

| 2015 | South Korea | 33 | 26 | 1 (3.8)e | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [48] |

| 2015 | Japan | 91 | 5 | 0 (0.0) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [92] |

| 2016 | Japan | 12 | 12 | 0 (0.0) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [79] |

| 2017 | Malaysia | 27 | 21 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [25] |

| 2017 | China | 26 | 26 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [70] |

| 2017 | Japan | 30 | 12 | 0 (0.0) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [78] |

| 2018 | Japan | 10 | 10 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [71] |

| 2018 | Germany | 325f | 61 | 1 (1.6) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | [63] |

| 2018 | Japan | 21 | 10 | 0 (0.0) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [52] |

| 2019 | Tunisia | 44 | 44 | 1 (2.3) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | [54] |

| 2020 | Japan | 17 | 8 | 0 (0.0) | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [89] |

| 2021 | Germany | 86 | 66 | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5)g | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | [49] |

| 2021 | Japan | 1516 | 1516 | 63 (4.2) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [75] |

| 2021 | USA | 135g | 71h | 2 (2.8) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [72] |

- Note: Studies are presented by year.

- Abbreviations: GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; NR, not reported.

- a Uncontrollable pustular psoriasis: eight (seven of these were on steroid therapy at the time of death), deaths clearly attributable to therapy: nine (seven to steroids and two to methotrexate), deaths to which steroids may have contributed: five, deaths to which methotrexate may have contributed: four; deaths due to massive exacerbation of GPP or toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by medication, one of which led to systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

- b Psoriatic inpatients.

- c Questionnaire sent to all in- and outpatients who visited 121 dermatological wards in 2004 for GPP.

- d Patients with pustular psoriasis.

- e One death reported in female patient with GPP of pregnancy.

- f Patient cohorts with pustular skin diseases.

- g One female patient died due to pneumonia after a flare of GPP that required hospitalization.

- h Data are from 135 hospitalizations not individual patients.

CONCLUSIONS

There are considerable challenges in the collection and interpretation of data on GPP prevalence, mortality and comorbidity. This is an inevitable consequence of the rarity of the disease and the sudden episodic nature of GPP flares, which limit the availability of suitable patients with active disease to power randomised controlled trials.91 Most studies included here are observational in nature (retrospective, clinical survey reviews and database analyses) and the majority include fewer than 100 individuals. Data derived from hospital settings are likely to include patients with more serious manifestations of GPP; with hospitalised inpatient records assumed to represent more severe cases compared with outpatient data. Patient characteristics also vary considerably, with study duration and treatment options rarely reported. Another key factor is the very recently accepted European consensus on GPP disease definition and diagnostic criteria,2 meaning that studies prior to 2017 and those in which diagnosis was left to clinicians' discretion may not be directly comparable. This is particularly relevant given the differences observed when comparing GPP prevalence, comorbidity and mortality data from European and Asian studies.

Overall, no consistent trends in GPP prevalence were identified, with the heterogeneity in estimates likely to be attributable to the considerable differences in study design and setting. These include variations in GPP disease definition, in countries and by year; for example, newer studies have presented various non-standardised disease measures, such as diagnosis at clinicians' discretion and utilisation of clinical global impression scoring.78 Varied data sources were used, comprising hospital records, national databases and insurance company audits. A wide range of patient inclusion criteria are also represented, with some studies including only hospitalised patients, juvenile patients or individuals referred to specialist centres, and some focusing exclusively on specific subtypes of psoriasis, such as plaque psoriasis. There was also considerable variability in sample size, with select studies reporting on a very limited number of individuals.

The impact of select diagnostic criteria was recently highlighted in a large Swedish population-based study published by Löfvendahl et al.,92 which reported a GPP prevalence of 90.1 per million persons in patients with a GPP diagnostic code of L40.1 from at least one physician visit. While these data are within the range reported here (1.76–124 patients per million persons), this study also reported that when a stricter case definition was applied (a diagnostic code of L40.1 at two physician visits, one of which was in dermatology or internal medicine), the prevalence of GPP decreased by approximately half, to 38 per million persons.92 Such variation highlights the need for a validated diagnostic algorithm to accurately identify GPP in electronic health record databases, and a requirement for similar diagnostic criteria to be used across studies to enable comparison of data.92, 93

Regarding mortality in patients with GPP, data here indicate that GPP flares are potentially life-threatening because of a range of complications, including sepsis and multisystem organ failure.72, 74, 84 The limited information available on reported mortality attributable to treatment means it was not possible to explore any meaningful relationships in these data. Data on mortality rates are further confounded by the recent availability of novel forms of therapy or, in earlier studies, by drug side effects. However, the high-mortality rates of GPP compared with other forms of psoriasis highlight the need for new treatments that improve the management of the disease. Further studies examining the long-term effects of different therapies or that are powered to differentiate between the presentation of GPP with other psoriatic conditions are also required.

Interconnected immunological pathways appear to drive the pathogenesis of both GPP and plaque psoriasis,81 and in line with previous reports,8, 12 this literature review identified a high rate of dual presentation, with almost half of patients with GPP also presenting with plaque psoriasis (median 46.4%, range 15.4%–83.0%), not significantly different from the estimate of 43.4% in the aforementioned study by Löfvendahl et al.92 The prevalence of GPP in patients with plaque psoriasis is also greatly increased compared with the general population.28-30 Here, the overlap in the presentation of these two diseases was greater than that with arthralgia or arthritis, the highest reported comorbidity in patients with GPP (median 16.7%). This would make plaque psoriasis a highly prevalent comorbidity of GPP, and vice versa. Ultimately, however, it has not yet been finally clarified pathogenetically whether GPP is a maximum variant of psoriasis or whether both diseases are independent entities that may coincide because of overlapping pathogenic pathways, and should therefore be regarded as comorbidities, i.e., the simultaneous occurrence of two independent diseases. GPP may also present with other forms of psoriasis and understanding these different phenotypes, and how they may affect treatment, will be key to developing effective, targeted therapies. A study from the International Rare And Severe Psoriasis Expert Network (IRASPEN), in collaboration with the Global Psoriasis Atlas, beginning soon will attempt to align phenotypic descriptions and diagnostic criteria for GPP, including biological samples and biomarkers to measure and correlate with clinical outcomes. Establishing new, or enhancing the limited number of current GPP registries, as well as more high-quality, long-term observational studies with adequate patient numbers and consistent follow-up duration that can address these issues, are required to provide a more accurate epidemiological assessment of patients with GPP.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJEs) and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors did not receive payment related to the development of the manuscript. Agreements between Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and the authors included the confidentiality of the study data. In the preparation of this manuscript James Parkinson, PhD from OPEN Health Communications (London, UK) provided medical writing, editorial support and/or formatting support, which was contracted and funded by BI. BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations. Open Access funding enabled and organised by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Medical writing support was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JCP declares paid activities as an advisor, speaker or consultant for Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis and Pfizer. SEC declares paid activities as an advisor, speaker or consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi and UCB. CEMG declares receiving grants or contracts from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, AnaptsysBio, BMS, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Janssen and Novartis; consulting fees from BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim and GSK; and speaker's fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, AnaptsysBio, BMS, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Janssen and Novartis. JFM is a consultant and/or investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavant Sciences, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharmaceuticals and UCB. AM declares receiving research grants, consulting fees and/or speaker's fees from AbbVie, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho Pharmaceuticals, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Nichi-Iko, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Torii Pharmaceutical, Ushio, and UCB. DMA declares receiving grants or contracts from AbbVie, Almirall, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, The LEO Foundation, Novartis and UCB. MV declares paid activities as an advisor, speaker or consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Medac and Novartis.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.