Influence of dietary supplementation of short-chain fatty acid sodium propionate in people living with HIV (PLHIV)

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding sources

Propicum® was donated by Flexopharm Brain GmbH & Co. KG.

REG. NUMBER: Ethical Committee of the medical faculty of the Ruhr-University Bochum: 16-5846.

Abstract

Background

Non-AIDS-associated chronic diseases in HIV+ patients have been on the rise since the advent of antiretroviral therapy. Especially cardiovascular diseases and disruption in the gastrointestinal tract have limited health-related quality of life (QoL). Several of those complications have been associated with chronic systemic inflammation. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), with propionate as one of the major compounds, have been described as an important link between gut microbiota and the immune system, defining the pro- and the anti-inflammatory milieu through direct and indirect regulation of T-cell homeostasis. The effects of dietary supplementation of sodium propionate (SP) in people living with HIV (PLHIV) have not yet been investigated prior to this study.

Objectives

To investigate the impact of SP uptake among PLHIV and its relevance to improve QoL, the study aimed to investigate metabolic, immunological, microbiome and patient-reported QoL-related changes post-SP supplementation with follow-up.

Methods

A prospective, non-randomized, controlled, monocentric interventional study was conducted in WIR, Center for Sexual Health and Medicine, in Bochum, Germany. 32 HIV+ patients with unaltered ART-regimen in the last three months were included. Participants were given SP for a duration of 12 weeks in the form of daily oral supplementation and were additionally followed-up for another 12 weeks.

Results

The supplementation of SP was well tolerated. We found an improvement in lipid profiles and long-term blood glucose levels. A decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines and a depletion of effector T cells was observed. Regulatory T cells and IL-10 decreased. Furthermore, changes in taxonomic composition of the microbiome during follow-up were observed and improvement of items of self-reported life-quality assessment.

Conclusion

Taken together, the beneficial impact of SP in PLHIV reflects its potential in improving metabolic parameters and modulating pro-inflammatory immune responses. Thus, possibly reducing the risk of cardiovascular disorders and facilitating long-term improvement of the gut flora.

Introduction

While the prevalence of HIV-associated morbidity, mortality and the occurrence of opportunistic infections has diminished considerably with the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART), there has been a corresponding increase in the risk for other chronic diseases.1 People living with HIV (PLHIV) demonstrate higher risk of fatal cardiovascular disease than the general population,2 which is, like many other complications among PLHIV, associated with chronic inflammation or immunodeficiency.1-3 Another factor adversely affecting the quality of life (QoL) of HIV+ patients undergoing ART is a non-infectious, often chronic, diarrhoea4, 5 which has limited possibilities for management.6 The primary cause of such non-infectious diarrhoea in HIV+ patients receiving ART is the treatment itself, of which diarrhoea is a fairly common side effect.7 However, non-infectious diarrhoea can also derive from pathological effects of HIV on cells and on the immune system in the gastrointestinal tract.7, 8 A model trying to explain the emerging risk of non-AIDS-related morbidity emphasizes HIV-mediated mucosal disruption leading to chronic systemic inflammation.3

In recent years, the implications of the gut microbiome and its metabolites have gained increasing attention. One such group of metabolites are short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which are produced by multiple bacterial species in the intestinal tract through fermentation of dietary fibre and other resistant starches.9, 10 They are mainly used as source of energy for colonic epithelial cells or transported via blood stream to other tissues from where they intervene in the host’s cellular processes.9, 11 The most studied compounds of SCFA are acetic, propionic and butyric acids, with two, three and four carbons in their chemical structure respectively.11 They constitute 90-95% of the SCFA present in the colon.10 SCFA have been described as for their anti-inflammatory properties12, 13 and in the amelioration of the course of several diseases through a positive influence on autoimmune reactions and metabolic functions. In particular, its positive effects in multiple sclerosis,14, 15 Parkinson’s disease,16 cardiovascular diseases,17 inflammatory bowel disease,18, 19 respiratory inflammatory diseases13 and type 2 diabetes10, 20 have been demonstrated. The modulation occurs through activation of G protein-coupled receptors (FFAR2, FFAR3, GPR109a, Olfr78) and through acetylation and methylation of the host’s gene expression.11, 19, 21, 22 By acting as inhibitors of histone deacetylase (HDAC) they play an important role in epigenetically regulating the colonic regulatory T-cell homeostasis.9, 23 Orally administered SCFA have been shown to increase the amount of intestinal Tregs by enabling the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into regulatory IL-10 producing T cells.14, 23-25 SCFA have also been described to suppress the conversion into pathogenic TH1 and TH17 cells.26, 27 However, it has been indicated that SCFA can not only promote T-cell differentiation into regulatory T cells but also into less inflammatory TH1 and TH17 effector cells, depending on the cytokine milieu.28, 29 In addition, it has been found that SCFA facilitate primarily the extra-thymic generation of Tregs. Such a de novo Treg cell generation in the periphery was described to be especially potentiated by butyrate and propionate.30 While suppressing the pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-4, IL-5, IL-17a, IL-2 and TGFβ9, 10, 31, 32 SCFA have been documented to increase the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.9, 23, 28, 31, 33 A similar beneficial effect has also been reported during sodium propionate (SP) supplementation.14, 15, 34

Taken together, these reports draw our attention to the potential modulatory role of dietary habits in the control of infectious diseases. Likewise, the role of SCFA in the control of insulin sensitivity and hyperlipidaemia10, 20, 35-37 could also be potentially providing crucial benefits in compensating the negative effects of ART. Therefore, in the current study we evaluated the effects of SCFA-supplementation on metabolic and immunological parameters, as well as on the microbiome of PLHIV and patient-reported QoL. For better comparison of the effects we used SP as SCFA, since SP in particular has been used for dietary supplementation in recent studies.14, 15, 34

Methods

Study design and analysis

We conducted a prospective, non-randomized, controlled, monocentric interventional pilot study between April 2017 and December 2019 in the WIR, Center for Sexual Health and Medicine in Bochum, Germany to evaluate the effects of SP among adult PLHIV. The study was accepted by the Ethical Committee of the medical faculty of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum (Number 16-5846).

Inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 years, a diagnosis of HIV-infection with a viral load <50 copies/mL, an unchanged ART-therapy in the last three months and a signed informed consent form. Exclusion criteria were antibiotic treatment in the last 6 weeks, immunosuppressive therapy in the last 6 months, any malignant diseases in the last 5 years or severe bowel disease that can cause chronical diarrhoea. With a two-sided 5% significance level and power of 80%, a sample size of 20 subjects was determined necessary through the ANOVA F-test. 32 HIV+ patients were included in the study.

For the duration of 12 weeks the recruited patients were given SP orally twice a day in form of 500 mg Propicum®capsules (Visit 1–6). Visit 1 corresponds to baseline (B). The received dose of 1 g/day is about 0.014 mg/kg of normal body weight. In accordance with the EU guidelines (European Food Safety Authority, E281:sodium propionate) a maximum dose of 3 g/kg is allowed with no risk of toxicity. All patients were followed-up for another 12 weeks (Visit 7–9). Empty-stomach blood samples and stool probes were collected at baseline and Visit 9. Sociodemographic data as well as medication and medical history were collected at the beginning of the study. Other important changes, such as development of accompanying diseases, occurrence of any adverse events and potentially the improvement of bowel movement, were documented at each visit.

Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire analysis

The assessment of health-related QoL (Baseline, V6 and V9) was determined through the SF-36 questionnaire, a patient-reported survey of patient health.38 Its basic structure consists of 36 single questions, which are summarized into 8 subscales. The subscales can again be divided into a Physical and a Mental Component Scale (PCS, MCS). Each item comprises of a dichotomous yes/no question on a 6-point ordinal scale. The individual answers were then converted, as specified in the standardized manual, and transformed into a scale where 0 meant the worst possible state of QoL and 100 meant the best. For the statistical analysis only the data of subjects with a complete set of questionnaires (B, V6, V9) were used, which resulted in the total number of 23.

Biochemical measurements

- Metabolic parameters: glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), serum lipid profiles: cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)- and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol and c-reactive protein (CRP) were measured.

- CD4, CD8, CD3, CD19, CD8/38, natural killer cells (NK) and Human Leukocyte Antigen – DR isotype (HLADR)-Activated Cell count was measured by flow cytometry (FACS Canto II, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

- A phenotypic evaluation of T-cell subsets was performed by flow cytometry through lymphocyte surface markers (FACS Canto II with FACSDiva Software and FlowJo 9.0, BD Biosciences). For each individual analysis 20,000 CD4+ cells were measured. Subsets were determined through percentage expression of specific surface markers within the CD4+ compartment.

- Natural Tregs: CD3+CD4+CD25++CD127low.

- Th1 cells: CD3+CD4+CXCR3+CCR6−.

- Th2 cells: CD3+CD4+CXCR3−CCR6−.

- Th17 cells: CD3+CD4+CD161+CXCR3−CCR6−+.

- Cytokines were measured through Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) or ELISA. After centrifugation plasma from each visit was immediately frozen at −20°C and moved to −80°C for long-term storage.

- CBA: FACSLyric (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

- Enhanced Sensitivity Flex Set (BD Biosciences) for Human IFN-γ (561515), Human IL-17A (562143), Human IL-2 (561517), Human IL-10 (561514) and Human IL-4 (561510).

- ELISA: Infinite F50 (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland).

- Interleukin-23 ELISA, TGF-beta 1 ELISA (IBL International GmbH, Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland, BE53231, BE55041).

- The microbiome was analysed through next-generation sequencing of the hypervariable region V3-V4-V5 of the 16S rRNA gene (Illumina MiSeq, MiSeq Reagent Kit V2, MS-102-2003). The amplification and indexing were done through the Microbiota solution B-kit (Arrow Diagnostics) with the associated software ‘MicrobAT 1.1’. (SmartSeq s.r.l., Genua, Italy). Baseline and V9 groups that had 16S amplicon sequencing data value in at least 80% of the samples were analysed at different taxonomic classification levels (taxonomic ranks such as family, genus, or species). Inter-group coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean) was calculated to ascertain variance.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis to determine the effects of SP supplementation as well as the long-term effects was performed using descriptive statistics in SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For numerical data, the mean value and standard deviation were calculated. A linear regression analysis between baseline, end of SP supplementation (V6) and end of follow-up (V9) was performed, and the coefficient of determination (R-squared value) was estimated to measure how well the data fit the regression line. R2 > 0.9 indicates a stronger correlation than lower values.

Results

Sociodemographic data and clinical characteristics

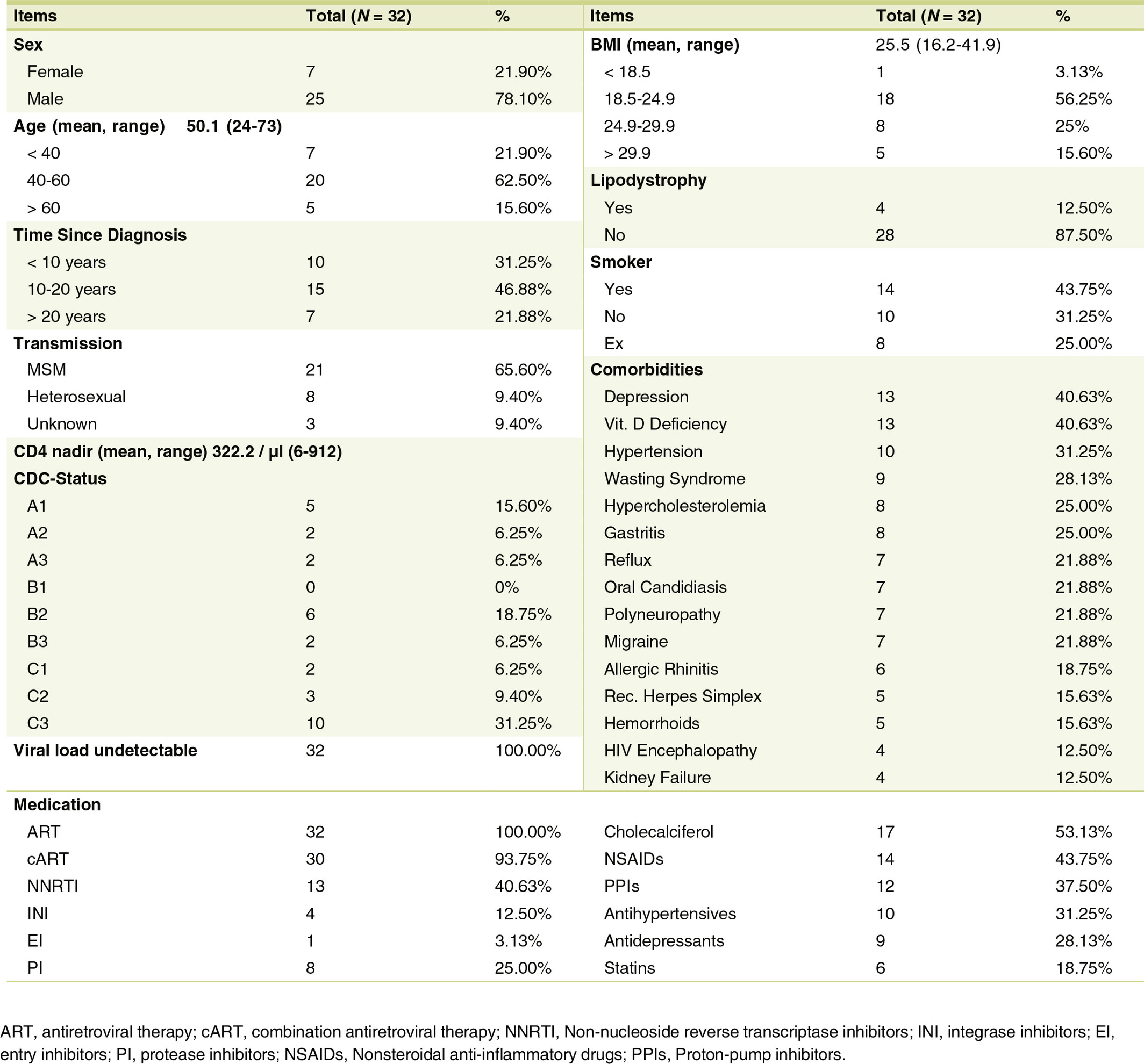

As shown in Table 1 the mean age of study participants (N = 32) was 50 years (24–73 years). The largest included age group was between 40 and 60 years old (n = 20, 63%). Only 15% were over 60 years old. 7 (22%) of the participants were female, the majority with 25 subjects (78%) were male. The HIV transmission of all female participants occurred through heterosexual contact. In the male collective, 21 out of the 25 participants were classified as men who have sex with men (MSM) transmissions (84%), one subject reported a heterosexual transmission. 3 participants did not provide any detailed information (12%).

For the largest group of participants, time since initial HIV diagnosis was 10–20 years prior to the study (47%). For almost a third of the participants (31%), < 10 years had lapsed since the first diagnosis, while 22% stated that the first diagnosis was made over 20 years ago. All subjects had an undetectable HIV viral load throughout the study. The mean value of CD4 nadir of the participants were 322 cells/µl (with a range from 6 to 912 cells/µl).

CDC stages: 28% of participants were classified as stage A, one fourth of the collective were of stage B. The highest number of participants (47%) could be subsumed in stage C, with CDC stage C3 being represented the most (Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, most subjects (56%) were in the normal weight range (BMI 18.5–24.9), 25% were overweight, 15% were obese (BMI >29.9). Only 1 participant was underweight with a BMI <18.5. Furthermore, 44% of the participants were currently smoking, 25% self-reported to be former smokers. 31% have never consumed any tobacco. The most represented comorbidities were depression and vitamin D deficiency. Hypercholesterolemia was found in 25% of participants.

Assessment of metabolic profile

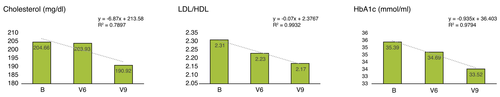

As seen in Fig. 1 HbA1c and HbA1c% concentration decreased noticeably (R2 > 0.9) at both end point measurements (V6 and V9). Cholesterol (R2 > 0.7) and the LDL/HDL ratio also showed a decrease throughout the whole study (R2 > 0.9). No changes in triglycerides and serum glucose level were detected.

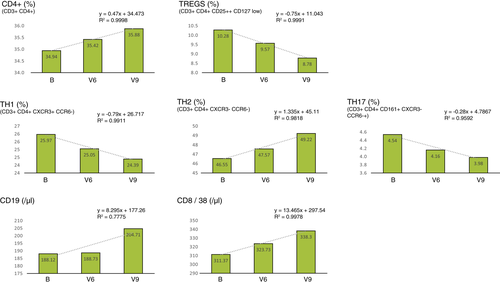

Evaluation of Th1, Th2, Th17, Tregs, lymphocyte subpopulations and cytokine profile

The results of the T-cell differentiation analysis are shown in Fig. 2. Among T-cell populations, the percentage of CD4+ T helper cells and Type 2 helper cells (Th2) increased (R2 > 0.9). Regulatory T cells (Tregs), Type 1 helper cells (Th1), T helper 17 cells (Th17) all decreased in their percentage (R2 > 0.9). By the end of the intervention, we observed an increase in CD4, CD8/38 (R2 > 0.9) and CD19 (R2 > 0.7). No changes in CD8, CD3, NK and HLADR act. cells were observed.

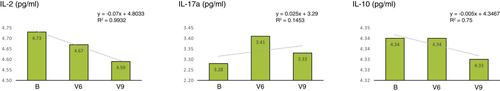

As seen in Fig. 3, determination of the inflammatory parameters showed a noticeable decrease in IL-2 (R2 > 0.9) and IL-10 (R2 > 0.7). Interestingly, we observed an increase in IL17-a during SP supplementation, which decreased again during follow-up. No changes were found in IFN- γ, IL-4 and TGF- β levels. IL-23 could not be measured as it was under the limit of quantification (LOQ) uniformly across all probes.

Microbiome and bowel regulation

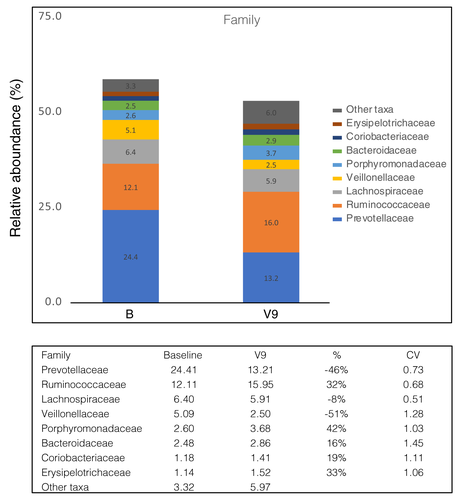

The analysis of the microbiome between baseline and V9 showed a noticeable change in the taxonomic composition as illustrated in Fig. 4. At the taxonomic level of family, a dominance of the prevotella enterotype was observed in the study collective compared baseline. By V9, we observed a tendency towards a reduction in Prevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae and Veillonellaceae. We have also found an increase in Ruminococcaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Coriobacteriaceae and Erysipelotrichaceae.

The supplementation of SP was well tolerated. As represented in Data S2, during SP supplementation about half of the subjects, especially those who have suffered from diarrhoea or loose stools, started reporting a subjective improvement of stool consistency and bowel regulation.

Assessment of health-related Quality of Life with the SF-36 questionnaire

The results of the questionnaire evaluation, which are shown in Table 2, can be compared to the standardized results of the German normative population from 1998.38 Overall, the scores of the HIV+ study cohort are at any point much lower as compared to the general population, without any exceptions.

| Scales | B | V6 | V9 | Data '98 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Function | 68 ± 28 | 61 ± 30 | 68 ± 28 | 85 ± 21 |

| Role Physical | 40 ± 40 | 50 ± 49 | 50 ± 38 | 82 ± 33 |

| Bodily Pain | 45 ± 29 | 45 ± 24 | 55 ± 25 | 67 ± 26 |

| General Health | 48 ± 22 | 48 ± 24 | 50 ± 20 | 66 ± 18 |

| Vitality | 36 ± 21 | 35 ± 25 | 38 ± 18 | 60 ± 18 |

| Social Function | 52 ± 27 | 53 ± 32 | 52 ± 30 | 86 ± 20 |

| Role Emotional | 36 ± 43 | 42 ± 47 | 35 ± 42 | 89 ± 27 |

| Mental Health | 50 ± 28 | 52 ± 22 | 53 ± 23 | 72 ± 17 |

| Physical Component Score | 43 ± 11 | 42 ± 11 | 45 ± 12 | 48 ± 9 |

| Mental Component Score | 30 ± 17 | 32 ± 17 | 29 ± 16 | 51 ± 9 |

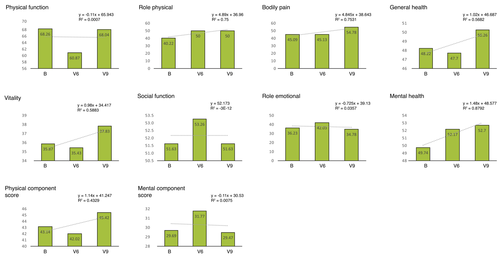

Corresponding to Fig. 5, the subscales in the PCS group are Physical Function (PF), Role Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP) and General Health (GH). The two parameters RP and BP increased slightly (R2 > 0.7) indicating the reduction of impairment through physical problems in everyday life and less physical pain. The subscales in the MCS group are Vitality (VT), Social Function (SF), Role Emotional (RE) and Mental Health (MH). The MH scale can be described analogue to the GH scale as the general perception of mental health in the individual. It showed a consistent rise (R2 > 0.8).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, dietary supplementation of SP in PLHIV has to date remained uninvestigated; therefore, we have for the first time evaluated the effects of SP supplementation, focusing on immunological/metabolic effects, changes in the microbiome and patient-reported QoL.

We observed a rise in CD4+ cell count, a decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines and a decrease in Tregs. Also noticeable were improvements of metabolic parameters, individual items in patient-reported QoL, taxonomic changes in microbiome and improvement of bowel regulation.

Consistent with previous findings,9, 10, 15, 23, 33, 34 we observed a decrease in IL-2, depletion of TH1/TH17 and increase in CD4+ cells. Interestingly, while this is in line with previously reported effects, the decrease in Tregs and the decrease in IL-10 appears to be different. And while in the context of HIV infection Tregs regulate the immune system to suppress inflammation and spread of virus, the suppression of the immune activation also promotes latent HIV-1 reservoir formation.39, 40 It has been hypothesized that targeting Tregs for depletion might be a potential target for HIV research with HDAC inhibitors as potential cure strategies.39, 41

Interestingly, while in the absence of infection short-chain fatty acids do increase IL10+ Tregs29 the opposite effects have also been described, depending on environment, organ and disease.31 Two examples are the SCFA-induced inhibition of lipopolysaccharide stimulated IL-10 production12 and the increase in inflammatory cytokines in the liver during increased C2 levels.42 It should be noted that in the latter study the intervention has been performed with acetate as SCFA. It has been indicated that acetate has low to none HDAC inhibitor activity in contrast to propionate.9, 31 It remains unclear in which pathological contexts the SCFA functions may be altered.42 In addition, it has also been shown that higher than physiological levels of SCFA can cause dysregulated T-cell responses and cause an inflammatory response.43 While there are many studies describing a general dysbiotic state of the gut microbiome in PLHIV regardless of age,44-49 a representative study demonstrating the physiological levels of SCFA in the gut of PLHIV has not yet been executed. There are only limited, inconsistent studies describing SCFA levels. In an elderly HIV+ Mexican population, unbalanced faecal SCFA levels were demonstrated at significantly higher levels of propionic acid than in the corresponding HIV- control group.50 In contrast, a study performed in a Chinese HIV+ population demonstrated lower levels of SCFA.51 It is unclear what the actual SCFA basal levels are in German PLHIV, and how they contextually vary with age and sexual preferences. It is also unclear if higher or lower physiological levels may affect the outcome of SP supplementation.

In our HIV+ study cohort, the analysis of taxonomic composition of microbiome revealed a dominance of the Prevotella enterotype, thereby providing a rationale for study participants with looser stool.52 Consistent with our observation, such an enrichment of Prevotella has also been independently reported by other studies in PLHIV45-47, 53-55 and MSM.44, 56-58 It is important to note within this context that SCFA are fermented among others through Prevotellaceae. In our cohort, Prevotellaceae decreased by the end of the study, with about half of the cohort reporting a subjective improvement of stool consistency during the intervention. Furthermore, our data demonstrated lower basal Ruminococcaceae in PLHIV, that increased upon SP supplementation. Other studies describing common markers of PLHIV-microbiome found a relative depletion of Ruminococcaceae. Ruminococcaceae are not only associated with anti-inflammatory properties and gut homeostasis,44, 59, 60 but its depletion has also been described in young adults with depression.61 Interestingly, depression was also the most common comorbidity in our study group.

Our data demonstrate metabolic changes post-SP supplementation, such as a decrease in total cholesterol, LDL concentrations and in HbA1c. SCFA have been reported to participate in the glucose homeostasis by reducing serum glucose levels and insulin resistance.10, 20, 35, 36 This may be due to the stimulation of the release of the anorectic gut hormones peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1).62, 63 Furthermore, a recent study has suggested that SCFA could reduce lipogenesis and enhance lipolysis through regulating related hormones and genes,64 which supports previous findings of blood lipid profile improvements.37, 65 This indicates that the mechanisms underlying beneficial metabolic actions of SCFA could also work in an HIV+ cohort. These and improvements concerning bowel regulation were associated with a better QoL. Despite our increased understanding of the impact of SP supplementation on PLHIV, the relationship between HIV infection and SCFA remains undeciphered at several levels and hence warrants further in-depth study.

Limitations of our study are that it was designed as a monocentric study with only a small number of subjects, a short duration of oral supplementation without documentation of nutrition and the absence of a standardized scale for stool consistency. Therefore, randomized controlled trials with a larger cohort are needed to further investigate the clinical effects of SP supplementation in PLHIV.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study. We thank the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, the diocese of Essen, the city of Bochum and Katholisches Klinikum Bochum for their support in setting up the WIR centre. The analysis of cytokines and microbiome was performed in cooperation with the MVZ Laboratory Krone GbR. Dedicated to the memory of Dr. med. Ulrich Matthes. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Patient consent

Obtained. The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publish their case details.

Open Research

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.