Characterizing clinicopathological and immunohistochemical findings in dermatomyositis panniculitis

Abstract

Linked article: This is a commentary on P. Santos-Briz et al., pp. 1352–1359 in this issue. To view this article visit https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14932

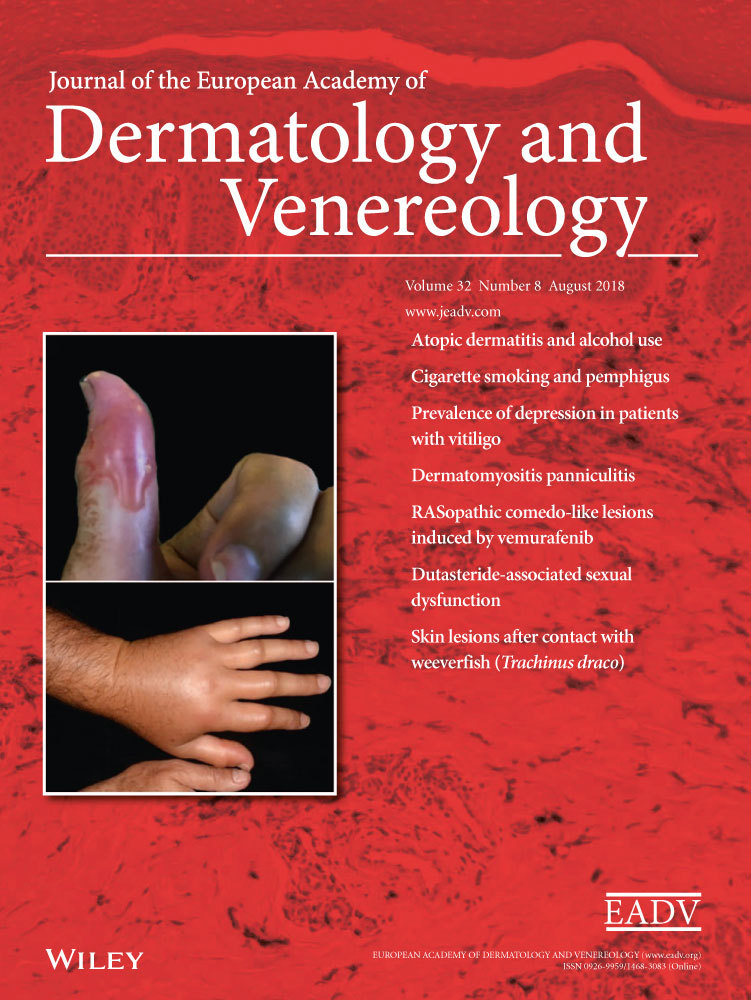

Dermatomyositis (DM) belongs to the group of idiopathic inflammatory myositis characterized by skin manifestations and inflammation of skeletal muscles; however, this feature may not be present in clinically amyopathic DM.1, 2 Muscle involvement may precede the skin lesions, occur simultaneously or follow by several weeks or months. Patients with the classic adult (not the juvenile) DM and patients with the amyopathic form of the disease have a strong association (18–25%) with malignancies.3 Therefore, adult patients with DM should undergo screening investigations.4 Pathognomonic skin changes are lichenoid confluent papules (‘Gottron papules’) over the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints and painful periungual erythema with dilated capillaries and splinter haemorrhage. In addition, the disease is characterized by the heliotrope rash with periorbital oedema in the acute stage of DM. Moreover, the heliotrope eruption at the V area of the neck (‘V sign’/'shawl sign’) and over knees and elbows as well as nail-fold changes, painful periungual erythema, poikilodermatous changes and scaly dermatosis on the scalp accompanied by severe pruritus and burning are further characteristic features of the disease.5 A sunburn preceding the onset of DM has been reported, and skin manifestations may exacerbate after UV irradiation in photosensitive patients.6

Rare skin manifestations in DM are panniculitis, follicular hyperkeratosis, flagellate erythema, mucinosis, erythroderma and oral mucosa changes.1 Panniculitis occurs in juvenile and adult DM, as painful-indurated, isolated or confluent nodules on buttocks, arm, thighs and abdomen. DM panniculitis was originally described by Weber and Gray in 19247 and may or may not be associated with other characteristic skin lesions of the disease. In contrast to panniculitis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the face is usually spared. The pathogenesis of panniculitis in DM is still unclear, but several factors such as environmental triggers, genetic predisposition and immune- and non-immune-mediated mechanisms play a role in the development of DM.1 Histological examination shows a lobular panniculitis with lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate, local liquefaction degeneration at the dermo-epidermal junction, and membranocystic changes. In addition to panniculitis in patients with SLE, the main histopathologic differential diagnosis of DM panniculitis is subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. Inflammatory changes in the subcutaneous fat can induce over time calcinosis, but calcification usually occurs late in DM without preceding clinical panniculitis.8

In this issue of the Journal, Santoz-Briz et al.9 studied 18 patients with DM panniculitis by analysing clinicopathological and immunohistochemical findings to provide a better characterization of this uncommon cutaneous manifestation. All cases presented with erythematous nodules or plaques in the subcutaneous tissue, in the lower and/or upper extremities. The number of panniculitis lesions (up to 15) was variable, and the head and trunk were not involved, except one patient with nodules on the face. Only one patient showed panniculitis as the initial manifestation of DM with anti-MDA5 antibody and rapid progressive interstitial pneumonia. In addition to panniculitis, all patients presented with characteristic skin lesions of DM and with proximal muscle weakness prior to the diagnosis of panniculitis. In none of the cases, malignancy was associated with DM panniculitis; therefore, this rare type of DM seems to be associated with less aggressive forms of the disease. In the literature, however, single cases have been described in association with neoplasm, such as ovarian adenocarcinoma,10 parotid carcinoma11 and rhabdomyosarcoma.12

On skin biopsy, it can be supported that the inflammatory infiltrate is mostly composed of small lymphocytes, and plasma cells are mainly detected at the periphery of lymphoid aggregates.9 Moreover, abundant interstitial mucin deposition between collagen bundles of the dermis and the subcutaneous connective tissue is also frequently seen.13 In late-stage lesions, histiocytes and lipophagic granuloma are predominant, whereas chronic lesions show hyaline necrosis of the entire fat lobule, with possible secondary calcification. Using immunohistochemistry, it can be demonstrated that T helper cells are predominant with abundant CD79a- and CD138-positive plasma cells at the periphery of the fat lobules.9 B lymphocytes are also seen in the lymphocytic aggregates with germinal centre formation, and small aggregates of CD123-positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells are usually present in the infiltrate of active lesions.

As mentioned by the authors, panniculitis lesions show a better outcome than other skin lesions in DM; however, a better response is seen for the muscular disease than for the cutaneous manifestations.9 In general, treatment options for DM are mainly based on case series, retrospective reviews, open trials and expert opinions.3 Moreover, therapeutic strategies are dependent on the subtype of DM, the severity of disease, individual patient preference, risk–benefit ratio, the presence of any associated systemic organ manifestation and relevant comorbidities. Initial treatment for skin lesions in DM usually consists of photoprotection, topical corticosteroids and antimalarials, and methotrexate (MTX) is often used as a second-line option. If MTX fails, mycophenolate mofetil or intravenous immunoglobulin may also be considered. Recent understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of DM enabled the development of biologicals, which target molecules such as CD20-positive B cells or tumour necrosis factor-α.14 Therefore, rituximab may be an alternative treatment option for patients with difficult-to-treat DM, both in the adult and the juvenile type of the disease.1 In addition, autoantibodies (i.e. anti-p155 and anti-MDA5) and laboratory data may result in new therapeutic strategies, but translational research is still warranted resulting in treat-to-target options for individual patients.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.