Preparing adults with intellectual disabilities for their future: How do support services staff view their role?

Abstract

Background

Person-centred service delivery underpins current approaches to working with individuals with intellectual disabilities. We investigated views of staff from a service organisation regarding their roles in creating desired futures for adults with intellectual disabilities.

Methods

Data were gathered from staff of a large organisation that provided a range of services to adults with intellectual disabilities. Respondents were asked to describe their role in assisting an individual with intellectual disability to meet their goals for the future. Responses were analysed using a text analysis programme.

Results

Two major themes were identified: ‘Support for self-determination’ and ‘Business-as-usual’. These themes were not entirely separate but had some overlap. There were indications that staff experienced competing demands in their role(s).

Conclusion

Although central to person-centred planning, staff who work with adults with intellectual disabilities may not see support of self-determination as a key factor in creating a desired future.

1 INTRODUCTION

Roles for staff who work in organisations providing services to adults with intellectual disabilities have changed substantially over the last few decades (see García Iriarte et al., 2016; Iacono, 2010) and these now include creating and maintaining opportunities for their clients inside and outside their organisation (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2012; Kilroy et al., 2015). This paper reports on the views of staff, working in one organisation providing services to adults with intellectual disabilities, about their roles in supporting clients to obtain their desired futures.

The change in staff roles reflects, in part, a changing view of the kind and quality of life that individuals with intellectual disabilities should expect. In Australia, the site of this study, there is an expectation of the national funding scheme that these individuals will experience an ‘ordinary life’ (NDIA Annual Report, 2015–2016). The concept of an ordinary life as defined by the Independent Advisory Council of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Independent Advisory Council to the National Disability Insurance Scheme, 2014) incorporates a number of aspects that reflect the lives of Australian adults in the 21st century. These are experiencing a sense of belonging and being actively engaged with one's community, making a contribution and being able to challenge oneself, being active in decision-making related to one's life, and having autonomy. Current policy directions and service provision for adults with intellectual disabilities reflect these priorities, generally focusing on increasing social inclusion and developing opportunities and skills for self-determination (Australian Government Department of Social Services, 2013), with these priorities also underlying service provision in other nations (Department for Work and Pensions and Office of Disability Issues (UK), 2019 [UK]; McColl et al., 2017 [Canada]; Shogren & Turnbull, 2014 [USA]).

Self-determination—that is making decisions for oneself—is central to the understanding of adult functioning (see, e.g., Palmer, 2010), and thus to the concept of an ordinary life for adults with disabilities. Self-determination requires the development of certain skills (e.g., decision-making) and the opportunity to practise those skills (Wehmeyer & Bolding, 2001). Choice and control are central to the construct of self-determination (Bogenschutz et al., 2019). Self-determination occurs when individuals act in a way that is volitional and in keeping with their own preferences. There are a number of studies that have shown a predictive association between self-determination and later positive outcomes, including inclusion in the community (Di Maggio et al., 2019; Shogren et al., 2015).

Making choices that are in keeping with one's understanding of self and one's values is understood to reflect autonomy, a construct closely connected to self-determination (Moore, 2020; Wullink et al., 2009). The United Nations Convention on the Rights for Persons with Disabilities (2006) recognises the right of those with an intellectual disability to receive support to develop their autonomy and autonomy supportive environments have been shown to promote self-determination in multiple populations (e.g., Moore, 2020; Shogren et al., 2017; Slemp et al., 2018); however, environments, including staff (inter)actions, may also undermine or prevent the enactment of self-determination.

Unequal power has remained a consistent aspect of relationships between clients with disabilities and those who are tasked to support them (e.g., European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2012), and this has implications for the way staff understand their roles. In a study that followed 16 adults with intellectual disabilities as they moved from congregate living to living in the community, García Iriarte et al. (2016) focussed on the role of staff in the move. Their data made evident the differing views that staff held as they negotiated their new role, with some taking responsibility for even minor decisions such as the clothes an individual wore, while others saw themselves as an advocate for the individual(s), with responsibility to push for client choices to be respected and acted upon. Some staff recognised that their role had changed substantially in response to the move, from one of care provision to one that was more aligned with providing support, and most reported a change in the way they viewed the individuals with whom they worked, in that the individuals were more likely to be seen as people with rights and capabilities.

In the context of discussions about the development/maintenance of intimate relationships with staff supporting adults with intellectual disabilities, Bates et al. (2020) found staff struggled with finding a balance between self-determination and control. While this was a self-selected group who were mainly supportive of the rights of individuals with intellectual disabilities to have sexual relationships, there were some who disapproved. There were also some staff who did not really see decisions about sexual relationships to be the purview of the individuals themselves: for example ‘I definitely need to know more about “what” the system allows…’ (p. 6).

Staff views of their roles with respect to supporting adults with intellectual disabilities to achieve their aspirations is one critical aspect of creating environments that are supportive of self-determination. The study reported in this paper is one element of a larger study focussed on the creation of futures of adults with intellectual disabilities.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants and setting

Participants were staff drawn from a large service provider which had adopted person-centred support as central to its operation; however, congregate work situations and group homes remained part of their offerings. Staff were recruited to the study via announcements about the project in staff newsletters and via the electronic communications used by the organisation. Staff who were willing to share their contact details with the researchers were entered into a draw for a prize to attend a social function hosted by the organisation. Personal details were not required, and staff could choose to remain anonymous if they preferred. Identifiers were separated from the data before analysis. It was made clear to staff that responses would not be shared with any member of their organisation. One hundred and seventy-three staff members, primarily front-line staff working directly with clients with intellectual disabilities, provided information about their perceived role, giving a response rate of 10.6% of the potential pool.

2.2 Data collection

Staff were provided with two vignettes—one for a male (George) and one for a female (Katie)—that described an individual's current circumstances as well as some of their aspirations for the future (see Appendix). Respondents were asked to choose one vignette and to describe the life of that individual in 5 years, reported in Cuskelly et al. (2021). They were then asked to describe the roles they could take in supporting the adult to achieve that future. The focus of this paper is this latter part of the data collection. All responses were collected via a secure, web-based survey with consent provided prior to entry to the survey. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the ethics committee of The University of Queensland (#2013000014).

2.3 Data analysis

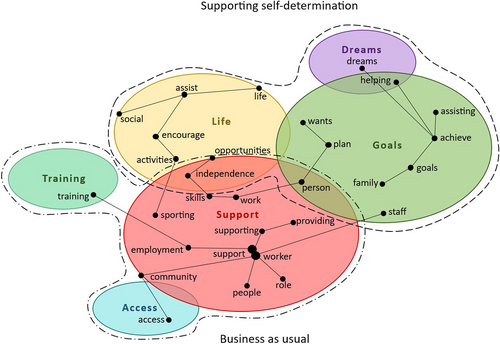

The text analysis tool, Leximancer (Smith & Humphreys, 2006), was used to identify themes in the respondents' answers to questions about the roles they would take in supporting the adult in the vignette. Leximancer provides both a content analysis of the frequency with which words appear and a matrix of the co-occurrence of words in the text. Leximancer draws together words that appear together in the text to create concepts which are then grouped into themes. Leximancer does not require that the term used as a theme label appear in text categorised under that theme; rather the programme transforms co-occurrences of words into semantic patterns, drawing on past learning, not just the document being analysed. The resulting semantic network can then be presented visually as a concept map which shows the connections among the concepts derived from the text as well as relative importance. Relative importance is indicated by colour (not size) of the circle representing the themes, with hot colours (red/orange) being more important than cool colours (blue/green). See Spina et al. (2021) for further description.

There is empirical support for the use of automated content analysis tools such as Leximancer. Nunez-Mir et al. (2016) conducted a comparison of results produced by manual analysis with those of Leximancer and concluded that the automated approach was at least as good as the manual approach, with some evidence that it may be even more sensitive in identifying themes. In addition, as argued by Nunez-Mir et al., the use of this approach reduces concerns regarding coder bias. Finally, in their comparison of available automated content analysis tools, Leximancer was found to meet five of six desirable inherent characteristics, outperforming other tools. Leximancer guidelines alert users to the fact that the concept map produced through the analysis may be somewhat unstable and recommend re-running the analysis multiple times to test the stability of the map (Leximancer Pty Ltd, 2018).

In this study, the text used in the analysis was the written responses from staff in answer to the question about their roles. Typically, a large number of concepts are generated by the analysis and these are then grouped into themes, labelled with the name of the most central concept. This label can be changed by the researcher(s) to better reflect the content of the theme. We ran 10 iterations of the analysis to ensure the output was stable. Following Cheng and Edwards (2019), we also undertook higher order theorising, using the thematic clustering produced by Leximancer to determine if the clusters reflected any overarching theme(s). This was undertaken through discussion between authors Cuskelly and Moni, and then confirmation by the remaining authors.

3 RESULTS

The Leximancer analysis proved stable after 10 runs and presented two distinct clusters (see Figure 1). These clusters were identified as overarching themes and were labelled ‘Supporting-self-determination’ and ‘Business-as-usual’. ‘Supporting-self-determination’ comprised ideas about being guided by the goals and desires of the adult with intellectual disability. ‘Business-as-usual’ reflected the ideas of support, with the central idea of the support worker role, along with access and training. The theme of support connected the two higher-order clusters, overlapping a little with the themes labelled goals and life. The material classified in this analysis was the textual responses—it was not the individuals who were classified—and it is possible that some participants provided a response that contained elements of both themes. The themes relevant to ‘Supporting self-determination’ received almost half the number of mentions compared with those related to the ‘Business-as-usual’ cluster (see Table 1).

| Theme (N hits) | Related concepts | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting self-determination | ||

| Life (47) | Life Assist Opportunities Social |

helping find avenues for her to achieve her goals and enhance her life [R104] assist George to achieve his aspirations in life [R97] by helping him to become more independent, looking for paid job opportunities, social skills and perhaps sex education from local resources [R171] |

Goals (21) |

Goals Achieve |

my role could be to have the discussion with Katie, her support workers and family to identify her goals. then point her in the right direction in order to achieve these goals [R81] ensure he is provided with choice and information about opportunities. support him to make his own decisions [R39] |

Dreams (7) |

Dreams | encouraging to explore his dreams and find out is it realistic and find a path to achieve his independence and choices [R72]; provide information to her and her family about how to pursue some of the supports necessary for Katie to realise her dreams [R167] |

| Business as usual | ||

Support (116) |

Support Worker Work Community Skills People Supporting Providing Employment |

provide support to work on taking her into the community, better use her day time (supported) to experience new skills, activities and meet new people [R164] provide transport for George to attend community events and social outings. provide support for George to find employment or even be on site supporting George on the job or at study [R135] |

Training (13) |

Training |

training him in attending a supported employment service [R57] |

Access (10) |

Access | I could represent Katie's interests in negotiating access to her entitlements; community access [R167]; community access volunteering [R92] |

The ‘Supporting-self-determination’ overarching theme comprised a cluster of three themes labelled ‘goals’, ‘life’ and ‘dreams’. The themes of ‘goals’ and ‘dreams’ had some minor overlap; however, ‘life’ appeared alongside ‘goals’ and did not overlap with the other themes in this cluster. The term ‘achieve’ was often found in proximity to ‘goals’ (see Figure 1), suggesting a focus on self-determination. Examples drawn from the respondents' texts include: being a voice for him to help him achieve his goals [R156]; making suggestions to help achieve goals and to set new goals [R29].

The ‘Business-as-usual’ cluster also contained three themes, labelled ‘support’, ‘access’ and ‘training’. The theme labelled ‘support’ was the dominant theme produced by the analysis (coloured red). This theme was referenced at more than twice the level of the next most common theme which was ‘life’ (see Table 1). The focus here was on support for daily activities without an indication if the impetus came from the individual him or herself: provide support to work on taking her into the community, better use her day time (supported) to experience new skills; Upskill Katie in respect to everyday living skills [R148]; support person in employment [R107]. The ‘support’ theme was pivotal to the ‘Business-as-usual’ cluster as it was often associated with interactions that did not include a reference to client self-determination, for example, Provide transport for George to attend community events and social outings. Provide support for George to find employment on even be on site supporting George on the job [R136]. Other words that were often in proximity to support included worker, people, providing and employment: organising lessons, taking him to meet people so he can maybe meet a nice girl, somewhere where people of his intellect go like ten pin bowling teams [R90].

The major theme in the ‘Business-as-usual’ cluster (’Support’) had some small overlap with two of the themes in the ‘Supporting-self-determination’ grouping. The word ‘support’ was sometimes used in the context of autonomy supportive activity, for example, providing support and advocacy where needed to empower George to fulfil his dreams [R150] and also in relation to assisting the organisation to move in the direction it had identified: support for reform, supporting an organisation that facilitates change & opportunities [R120]. There were intersections and connections among the themes with a link between the ‘support’ theme and that of ‘life’, these being connected though the ideas of skill development, independence and opportunities, for example, by helping him to become more independent [R171]; investigate safe systems to further the employment opportunities [R86]. As with the example provided by R171, these ideas were sometimes expressed in ways that indicated the respondent thought they were a good idea, rather than emanating from the person with intellectual disability.

There was evidence in the transcripts of the ‘Supporting-self-determination’ theme that a number of workers were very clear about their role being shaped by the individual with intellectual disability: help to set up a personal plan—a personal plan is like a contract to how we work together to achieve what it is that the person wants to achieve. / implement plan—research, staff match, work/listening—working on what you have heard the person say or wants to do [R99]. There were only a few responses that explicitly indicated a lack of expectation that the individual would/could act with self-determination: helping him to remain productive and safe [R87]; encouraging outings and activities [R161]. A small proportion of respondents (4%) stated that they were uncertain about what they could do to assist creating the future desired by the individual in the vignette and another 5% responded that they would be a support worker, essentially absolving themselves of any responsibility/agency in the way they carried out their role.

4 DISCUSSION

Two overarching themes—‘Supporting-self-determination’ and ‘Business-as-usual’—were identified in the analysis of staff responses about their role in supporting adults with intellectual disabilities to construct their future. The ‘Supporting-self-determination’ theme reflected recognition that the dreams and hopes of clients provide a guide for staff efforts, and that staff saw themselves as having some responsibility to work with the individual to achieve the life they wish. Responses fitting with this theme showed a commitment to person-centred practice, and an explicit understanding that adults with intellectual disabilities could and should set goals and direct their lives to meet their ambitions. The ‘Business-as-usual’ theme reflected a focus on the day-to-day concerns of staff in their roles with their clients. This theme was exemplified by expressions such as ‘support’, ‘provide’ and ‘organise’, suggesting that staff determined the directions of their activity in contrast to being directed by the desires and ambitions of the person with intellectual disability. These two positions reveal the tensions staff face as they engage with their work.

Acceptance of the self-determination of adults with intellectual disabilities and the usurpation of the decision-making role are incompatible, and yet, as indicated above, a staff member may have expressed ideas congruent with both the overarching themes. In essence, where staff are placed in a position of having to choose between a course of action that supports self-determination and one that prioritises their duty of care, their choice is likely to reflect their commitment to the principle of self-determination, their understanding of the capabilities of the person with whom they are working, and their consideration of the risk they perceive to themselves or the organisation.

The reality faced by staff is that they work in a system that has contradictory imperatives. They are expected to deal with competing demands of the individual, the organisation, and, at times, the requirements of other staff and clients. The dilemma experienced by staff as they attempt to incorporate self-determination with the requirements of duty of care in their interactions with their clients with intellectual disabilities have been revealed in several studies. For example, Clifford et al. (2018) found some staff were reluctant to work in ways that supported the self-determination of their clients as they perceived there were possible negative consequences both for the individual with intellectual disability and for themselves if they were held (or felt) responsible for poor choices and outcomes. In addition, Petner-Arrey and Copeland (2015) found that staff felt constrained in their support for self-determination by their organisations' priorities and mechanisms of service provision.

Staff who work in ways that retain decision-making power to themselves may hold views of people with intellectual disabilities as incompetent with respect to decision-making. For example, in their study conducted with 10 adults with intellectual disabilities and 10 support staff, Petner-Arrey and Copeland (2015) found that staff saw protection of their clients to be their primary responsibility. Pallisera et al. (2021) reported on interviews with 13 adults with intellectual disabilities living in supported living arrangements and 6 staff who provided support. Their sample included only those individuals who were already displaying high levels of autonomy in their lives, but they still found that 50% of them were constrained in making their own choices and these constraints were a reflection of the professionals' views of their individual capacities. The authors made the point that professional practices—based on staff views of capacities—limited opportunities available to the adults with intellectual disabilities.

In the current study, there were some staff who expressed the view that adults with intellectual disabilities had both the capacity and the (implied) right to determine their own future and there were few responses that explicitly indicated a lack of expectation that the individual would/could act with self-determination. Petner-Arrey and Copeland (2015) also reported multiple instances of staff actively struggling to support the autonomy of those they worked for, both by putting their own views on hold in order to support the person with whom they worked or ensuring that the service actually listened and acted on the preferences of the adult with intellectual disability.

There is a gulf between the emphases of policy documents regarding the life choices of individuals with intellectual disabilities (e.g., where to live and with whom) and the day-to-day choices that make up everyday living, which are generally about much smaller, reoccurring events such as what to wear or eat (see Antaki et al., 2009). Lloyd et al. (2021) found that some parents were not consistent in the view they took with respect to their adult child with intellectual disability, simultaneously espousing views that reflected the idea of competence (e.g., independent living was desirable and achievable) with those that suggested that protection was needed (e.g., sexual relationships were discouraged or even prohibited). This inner tension between views may also be at play within staff working in service contexts.

Recent work by Di Maggio et al. (2021) highlighted the importance of self-determination for adults with intellectual disabilities, including for the development of future goals. Organisations need to grapple with the challenging issues of identifying ways to promote self-determination in adults with intellectual disabilities while balancing this with their duty of care (Webber & Cobigo, 2014). Such an endeavour is likely to call for interventions that support the development of skills and propensities of individuals with intellectual disabilities to act in a self-determined manner, skill development and attitudinal change of staff, and policy development that explicitly addresses issues such as duty of care and risk taking. There is evidence that explicit teaching of self-determination can be effective, with concomitant positive outcomes (see Wehmeyer et al., 2017 for an overview) and that both formal (Wong & Wong, 2008) and informal (Cudré-Mauroux et al., 2020) interventions can support staff to become more effective in supporting the self-determination of their clients. There is little guidance in the empirical literature regarding the development of policy relevant to assisting staff to balance competing obligations with respect to self-determination and safety.

5 STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The focus of this study is novel and deals with an important issue. Staff views about their role in contributing to the attainment of desired futures are likely to be central to the opportunities available to adults with intellectual disabilities. The approach to data collection through the use of a vignette describing an individual—as opposed to questions that focus on those with intellectual disabilities in a general sense—is likely to have assisted participants to be specific in their response.

There is some ambiguity in the data as presented, which contributes to uncertainty about interpretation. Some participants provided responses which made their position very clear; others were brief and thus provided less insight. As an example, references to ‘goals’ did not always make clear if the goals emanated from the person with intellectual disability. While goal setting is central to person-centred planning (National Disability Practitioners, 2016), the approach adopted by the organisation from which respondents were drawn, it is possible that the usage of this term did not always reflect an orientation to self-determination.

We did not ask respondents to directly address if, or how, they would ensure that George/Katie were able to achieve their goals, although they were asked what role they would take in supporting them to achieve their aspirations as described in the vignette. One of the limitations of open-ended response formats is that it is not possible to be certain that absence equates to a lack of importance for the respondent; it may reflect a desire not to discuss the omitted content or that is it not a priority when time (to respond) is limited in some way. We need to be cautious about assuming that a lack of focus on self-determination in staff responses means that it was unimportant to them.

In this study, we did not collect specific data about position within the organisation, as to do so would have identified some respondents. However, different designations within an organisation bring different responsibilities, with, for example, direct support staff engaging in tasks that differ from those of management. The majority of respondents did work directly with the organisation's clients; however, some responses were clearly from individuals whose work was more removed. Being able to identify organisational position may have added some nuance to the understandings provided by this study. While the number of staff who participated in the study was quite large, it only represented 10.6% of potential respondents, thus possibly introducing unknown bias to the results.

6 IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The expectation that adults with intellectual disabilities will have ‘an ordinary life’ carries implications for the kinds of services they receive as they make decisions and work to create the future(s) they desire. Staff understandings of their roles impact upon their actions and their interactions with their clients. This study revealed that some staff who were dealing with adults with intellectual disabilities did perceive the support of self-determination to be central to their role; however, a substantial number of responses revealed an understanding of role that was focussed on ‘supporting’ the person, without the implication that the direction of this support would be guided by the person's wishes or desires for a particular future. Staff require training and on-going skill development as well as exposure to advocates and models of good practice if person-centred services are to become inherent to their understandings of their role. Understanding how staff with different levels of responsibility for service delivery construe their role and the role of other staff, especially those with direct contact with clients, is likely to enhance targeting of change efforts. Associated with this is the need to gather information from adults with intellectual disabilities about the nature of the supports they require in the pursuit of their desired futures.

The tensions staff experience between supporting the self-determination of adults with intellectual disabilities and the business-as-usual approach to their work needs further exploration to identify the sources of different understandings of their role. Both internal (e.g., attitudes and beliefs) and external (e.g., organisation demands and expectations) factors may contribute to staff views, and interventions are unlikely to be successful unless these are properly understood. Further examination of what constitutes effective interventions is warranted. Ratti et al. (2016) produced a sobering assessment of the evidence linking person-centred planning to improved outcomes for individuals with intellectual disabilities and so any attempt to promote change needs to be rigorously evaluated.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Staff who work with adults with intellectual disabilities are faced with competing demands in their employment. They are asked to support clients' self-determination; however, there are a number of factors that may interfere with their adoption of this as an important facet of their role. Organisational priorities, attitudes and beliefs about capacities of individuals with intellectual disabilities that promote a focus on support in the absence of a clear recognition and respect for the right of individuals with intellectual disabilities to self-determination in shaping their daily lives and futures need to be identified, challenged and addressed if this right is to be upheld.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council #LP120200281. We are grateful for the support of Endeavour Foundation who was a partner in this research. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Tasmania, as part of the Wiley - University of Tasmania agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

APPENDIX

STIMULUS VIGNETTES

George is a young man with a moderate intellectual disability living in your local community. He is living in supported accommodation and sees his family regularly. George attends services at your organisation for 2 days a week where he is well liked. One day a week he does chores with a support worker. On weekends he participates in a Saturday swimming club and he occasionally goes to the coast with his parents to see his grandparents. George likes cars and he sometimes goes to watch drag racing with his older brother. He has an ambition to own a red Porsche and to have a girlfriend.

Katie is a young woman with a moderate intellectual disability living in your local community. She is living in supported accommodation and sees her family regularly. Katie attends services at your organisation for 2 days a week where she is well liked. One day a week she does chores with a support worker. On weekends she participates in a Saturday swimming club and she occasionally goes to the coast with her parents to see her grandparents. Katie likes netball and sometimes goes to watch netball with her older sister. She has an ambition to live in London and to have a boyfriend.

Consider George/Katie in the context of the family and local community in which s/he lives. In 5 years' time, what do you think George/Katie's life will be like. Try to imagine and describe it.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.