Psychological and social outcomes of befriending interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review

Abstract

Background

Befriending is an intervention intended to provide companionship and support to socially isolated populations. This review aimed to understand the key characteristics and psychological and social outcomes of befriending interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities.

Methods

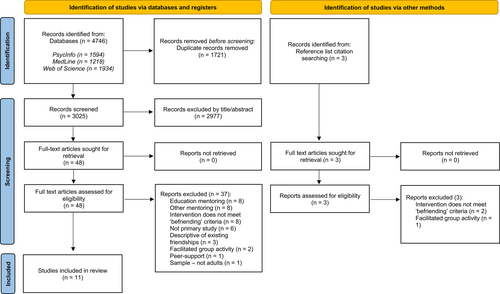

Systematic searches of electronic databases (PsycINFO, MedLine and Web of Science) identified 11 studies for inclusion. A narrative synthesis of the findings was completed, along with critical appraisal of study quality.

Results

Increased community participation, positive changes to social networks and mood were frequently reported outcomes for befriendees. Increased knowledge, new experiences and opportunities to ‘give back’ were most reported for befrienders.

Conclusions

The review highlighted that existing research in this field is limited in scope and methodologically diverse. Future research should focus upon the effectiveness and long-term impact of befriending interventions, understanding the mechanisms of change, and eliciting the views of people with intellectual disabilities on their experiences.

1 INTRODUCTION

Friendships are important: they provide companionship and emotional support and facilitate community integration and development of social networks. Making and maintaining friendships promotes individual wellbeing, offers opportunities to share pleasure and enjoyment, and provides a sense of valuing others and feeling valued by others (Peel et al., 2009).

Friendships impact quality of life for people with intellectual disabilities, directly influencing the domains of emotional wellbeing, interpersonal relations and social inclusion (Schalock et al., 2002). However, individuals with intellectual disabilities face barriers to social inclusion and often find it hard to make and maintain friendships (Abbott & McConkey, 2006; Merrells et al., 2019). Social networks are frequently reported as small and made up primarily of family members, paid carers and other people with intellectual disabilities (Duggan & Linehan, 2013; Emerson & McVilly, 2004; Verdonschot et al., 2009). Prevalence of loneliness is higher compared with the general population (Alexandra et al., 2018; Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2014) and barriers impact upon making new friends and participating in the community (Abbott & McConkey, 2006; Mayer & Anderson, 2014).

In the United Kingdom, the government has long sought to enable people with intellectual disabilities to develop friendships and engage in a variety of community activities (Department of Health, 2001). Many initiatives have been implemented, to varying effect (Bigby et al., 2018; Duggan & Linehan, 2013; Howarth et al., 2016). One particular intervention that aims to improve quality of life and wellbeing and enhance social support is ‘befriending’, which seeks to develop a one-to-one, friend-like relationship, usually organised by a charitable organisation (Balaam, 2015; Dean & Goodlad, 1998). Befriending has been implemented internationally across a range of populations considered to be vulnerable to social isolation, including individuals with physical health or mobility problems (Rantanen et al., 2015; White et al., 2012), socially isolated older adults (Mountain et al., 2014), carers for people with dementia (Charlesworth et al., 2008), people experiencing mental health problems (McCorkle et al., 2009; Priebe et al., 2020) and people with intellectual disabilities (Southby, 2019; Tse et al., 2021).

Despite its popularity, the evidence base for befriending is limited. One meta-analysis of befriending across various populations (including one study of people with intellectual disabilities), found a small positive effect for combined primary outcomes, including quality of life, loneliness and depression but no significant benefit on single outcomes (Siette et al., 2017). Another meta-analysis across a range of populations found a modest positive effect on depressive symptoms but none on perceived social support (Mead et al., 2010).

There is comparatively more evidence for befriending in the mental health field. One review found that befriending practice varies widely with regard to implementation of personal boundaries, expected relationship duration or the extent to which it is viewed as a professional relationship or a friendship (Thompson et al., 2016). Individual studies have reported that mental health befriending increases community participation and fosters new skills (Mitchell & Pistrang, 2011), increases numbers of social contacts (Priebe et al., 2020), and offers volunteers opportunities to enhance their personal growth whilst supporting others (Cassidy et al., 2019; Klug et al., 2018).

Reviews focusing on inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities have considered broader health and social care interventions, such as person-centred planning or skills-based sessions (Howarth et al., 2016), ‘natural supports’, such as existing family and social networks (Duggan & Linehan, 2013), or participation in sport (Zhao et al., 2021). The outcomes of befriending interventions for people with intellectual disabilities and whether these foster friendships or promote social inclusion have not been specifically reviewed. Strategic decisions around commissioning of services, service management and best practice for befriending schemes could all be shaped by a greater understanding of the evidence on befriending for people with intellectual disabilities.

1.1 Review aims

This review aimed to outline the key characteristics of befriending interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities, to explore and synthesise the psychological and social outcomes of such interventions, and to identify future research directions required to advance the evidence base.

2 METHOD

2.1 Search strategy

The review was conducted following preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Systematic searches of the PsycINFO, MEDLINE and Web of Science databases were conducted in October 2021. Search terms were developed through scoping searches, review of published search strategies, and consultation with a subject specific librarian. Multiple diverse search terms for ‘befriending’ were utilised to retrieve all relevant articles due to an expectation of there being nuanced differences between befriending and other similar interventions. Search terms relating to (1) intellectual disabilities; (2) befriending; and (3) adults, were combined using an ‘AND’ Boolean operator. Searches and article selection were limited to peer-reviewed journals. See Table A1 in Appendix A for a full list of the search terms used in each database.

2.2 Eligibility

For the purpose of this review, befriending was defined as a one-to-one ‘friend-like’, emotionally supportive relationship, with a commitment over time, organised and supported by an external organisation, and where one party was deemed likely to benefit. We distinguished this from mentoring (which typically had more focus on pre-determined goals, training or teaching and was often related to particular transitions e.g., school, university, workplace), peer-support (where someone with intellectual disabilities supports another person with intellectual disabilities) or friendship (a more private, spontaneous relationship where the relevant parties would otherwise have met).

The inclusion criteria were (a) studies reporting findings on adults described as having intellectual disabilities and/or autism; (b) studies focused upon befriending interventions as defined above; (c) primary studies with any type of design, including quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods. Exclusion criteria were (a) studies not relating to befriending as defined, for example group interventions, peer-support, mentoring or one-off support; (b) studies focusing on friendship with a paid worker or family member rather than a volunteer; (c) secondary studies such as systematic reviews or meta-analyses; (d) discussion papers or meeting abstracts.

2.3 Study selection

References retrieved from the database searches were exported to EndNote X9 and systematically de-duplicated (Bramer et al., 2016). The titles and abstracts of remaining articles were screened for eligibility by the first author and the reference lists of these screened studies were manually searched for any additional references. Full texts for the remaining references were retrieved and reviewed for inclusion by the first and last authors. Discrepancies in decisions on whether to include certain studies were resolved through discussion

2.4 Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction form was developed based on the research questions, and data from each of the included studies was extracted. Narrative synthesis (Popay et al., 2006) was used to analyse the identified papers. This included tabulating outcomes, comparing differences and quality appraising each of the studies. The major findings were grouped into categories which were refined over the course of the synthesis through ongoing comparison and discussion.

2.5 Quality appraisal

The QualSyst tool (Kmet et al., 2004) was used to critically appraise the included papers. QualSyst provides a systematic, reproducible and quantitative means of assessing research quality across a broad range of study designs. It sets out separate criteria for assessing qualitative and quantitative methods (see Table B1 in Appendix B for an overview of checklist items). Studies were rated against the relevant checklist(s), scoring either yes (2), partial (1), no (0) or n/a for each item, dependent upon the extent to which they fulfilled the respective criterion. To increase the reliability of ratings, the first and last authors initially scored five studies independently before discussing any discrepancies in the scoring decisions. The first author then completed the rating of the remaining studies. For each study, a final summary score was calculated by summing the total score across relevant items and dividing by the total possible score. These summary scores were used as an overall indicator of the relative quality of the studies.

3 RESULTS

A total of 4746 references were retrieved from database searches, with a further three identified by searching reference lists (see Figure 1). The full texts of 51 articles were assessed for eligibility, resulting in the inclusion of 11 studies (see Table 1 for an overview). The studies, published between 1995 and 2021, were conducted in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Australia and Greece.

| Author (year) | Study design | Study focus | Location and sample | Data collection methods | Data analysis methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al. (2021) | Pilot RCT | Feasibility and acceptability of a future RCT of one-to-one befriending for people with intellectual disabilities and depressive symptoms | UK; 6 befriendees, 10 befrienders | Quantitative outcome measures (including Glasgow Depression Scale for People with Learning Disability), semi-structured interviews | Mixed—Linear regression, descriptive statistics. thematic analysis |

| Bigby and Craig (2017) | Case study | Qualities of a friendship between a person with and a person without intellectual disabilities, and factors supporting its development/sustainment | Australia; 1 befriendee, 1 befriender | Semi-structured interviews, participant observation | Grounded theory |

| Fyffe and Raskin (2015) | Qualitative | The programme design of a ‘Leisure Buddy’ programme, issues arising in implementation and initial outcomes | Australia; 18 befriending matches | Semi-structured interviews with coordinator, programme documentation review | Unspecified—qualitative synthesis |

| Green et al. (1995) | Qualitative | Changing perceptions of befrienders in early stages of an ‘arranged partnership’ | USA; 19 befrienders | Semi-structured interviews | Unspecified—qualitative synthesis |

| Hardman and Clark (2006) | Survey | Characteristics of and perspectives on a befriending programme | USA; 1145 befriendees, 1222 befrienders | Cross-sectional survey (multiple choice/Likert scale responses) | Descriptive statistics |

| Heslop (2005) | Qualitative | Key issues befriending services face, factors contributing to, and recommendations for, good practice | UK; 34 befriendees, 42 befrienders, 46 parent carers, 15 befriending scheme workers | Semi-structured interviews | Unspecified—qualitative synthesis |

| Hughes and Walden (1999) | Quasi-experimental | Impact of a befriending intervention upon social lives of residential service users | UK; 4 befriendees, 10 befrienders | Semi-structured interviews covering social network size, visit frequency, participation in activities | Mixed—Descriptive statistics, narrative extracts |

| Jameson (1998) | Survey | Evaluation of an existing programme, examining factors fostering stable relationships | USA; 25 befrienders | Cross-sectional survey (Likert scale responses) | Descriptive statistics |

| Mavropoulou (2007) | Qualitative | Development of two pilot befriending schemes for people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | Greece; schemes recruited 35 people with ASD, 82 volunteers | Unspecified | Narrative descriptions |

| Southby (2019) | Case study | Befriending as an opportunity for adults with learning disabilities to access mainstream leisure | UK; 4 befriendees, 4 befrienders, 3 staff members, 3 family members, 1 employer | Semi-structured interviews, participant observation | Thematic analysis |

| Tse et al. (2021) | Survey | Characteristics and challenges for befriending services, volunteer motivations and experiences | UK; 8 befriending service coordinators 58 befrienders | Cross-sectional survey (checklist, Likert scale, open-ended questions) | Mixed—Descriptive statistics, logistic regression, thematic analysis |

Two studies described particular befriending relationships using a case study design, two used surveys to evaluate existing schemes, two described the development of new schemes and two focused upon the experiences and challenges of befriending services. Additionally, one pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) looked at befriending and depressive symptoms, one quasi-experimental study examined impacts upon social network size and one explored the changing perceptions of participants as befriending relationships evolve.

Sample sizes ranged from two participants to several thousand participants. Data were most commonly collected through semi-structured interviews, with seven studies employing this method, whilst others used surveys and quantitative outcome measures. Six of the studies utilised qualitative analysis approaches, two presented only descriptive quantitative data and three employed mixed methods of analysis.

3.1 Critical appraisal of included studies

There was a broad range of quality appraisal ratings across the papers (see Table 2). The summary scores of the nine studies employing qualitative approaches ranged from 0.2 to 0.95, averaging 0.75. Scores were highest against the ‘question/objective description’ criterion (item 1). Performance against the ‘use of verification procedures’ criterion (item 8) was more mixed, with five studies fully satisfying the criterion requirements, and four studies not achieving them at all. ‘Reflexivity of account’ (item 10) scored lowest overall, with no studies explicitly addressing the impact of the authors' own personal characteristics. Of the five studies using quantitative measures, summary scores ranged from 0.6 to 1.0, averaging 0.82. These studies had high scores against the ‘method of subject selection or information sources description’ criterion (item 3), with clearly outlined sampling strategies. Scores were lowest for ‘controlling for confounding’ (item 12), with the two relevant studies (Ali et al., 2021; Hughes & Walden, 1999) deemed to have incompletely controlled for confounding factors.

| Study | Qualitative QualSyst scores | Summary score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Ali et al., 2021 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.95 |

| Bigby & Craig, 2017 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.90 |

| Fyffe & Raskin, 2015 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.95 |

| Green et al., 1995 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.70 |

| Heslop, 2005 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.85 |

| Hughes & Walden, 1999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.40 |

| Mavropoulou, 2007 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.20 |

| Southby, 2019 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.90 |

| Tse et al., 2021 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.90 |

| Study | Quantitative QualSyst scores | Summary score | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

| Ali et al., 2021 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.89 |

| Hardman & Clark, 2006 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 0.81 |

| Hughes & Walden, 1999 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.60 |

| Jameson, 1998 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 2 | 0.81 |

| Tse et al., 2021 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

- Note: 2, yes; 1, partial; 0, no; −, not applicable.

Whilst Kmet et al. (2004) did not specify cut-off thresholds, the authors debated whether to include the two studies with low appraisal ratings (Hughes & Walden, 1999; Mavropoulou, 2007). As this paper aimed to comprehensively review the existing evidence and its limitations, it was decided to include the studies. Study limitations and quality rating scores have been provided alongside the data synthesis to provide an indication of the validity/reliability of the findings.

3.2 Key characteristics of befriending interventions

The studies provided limited detail as to the characteristics of the external organisations supporting the befriending relationships. Whilst each organisation provided a befriending service to people with intellectual disabilities, whether these were disability specific organisations or mainstream community organisations was not always explicitly stated by study authors, with descriptors such as ‘community befriending services’ (Ali et al., 2021) or ‘charitable organisation[s] administering a befriending scheme for adults with learning disabilities’ (Southby, 2019) insufficient to understand if the organisation was specifically focused upon disability or intellectual disability. In some studies, the befriending was provided by pre-existing organisations catering to people with intellectual disabilities (Hardman & Clark, 2006; Jameson, 1998; Tse et al., 2021), and in others the provision was set up specifically at the time of the study (Fyffe & Raskin, 2015; Green et al., 1995).

3.2.1 Recruitment methods

The most common method of recruiting befrienders and befriendees, mentioned by six of the eight studies which detailed the methods used, was public advertising—ranging from newspapers and brochures to websites and social media. For those studies where college students acted as befrienders (Green et al., 1995; Hardman & Clark, 2006; Jameson, 1998; Mavropoulou, 2007), recruitment was conducted on-campus through classes, adverts and student organisations. Befriendees were typically recruited from existing intellectual disabilities services and charities, through waiting lists and word of mouth.

3.2.2 Matching criteria

Six of the eleven studies outlined common criteria to match befriending pairs, including interests, age, gender, location, availability, personality, severity of disability and volunteer experience, with interests, age and gender most frequently reported (see Table 3). All used shared interests as criteria for matching, with Tse et al. (2021) reporting this as the most common criterion from their survey. Heslop's (2005) paper setting out best practice recommendations did not present specific guidance on matching criteria, potentially implying that an idiosyncratic approach is required, whilst Fyffe and Raskin (2015) noted that successful matches were sometimes formed contrary to the preferences participants believed would be important (e.g., age, gender, interests).

| Study | Interests | Age | Gender | Location | Availability | Personality | Severity of disability | Volunteer experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al., 2021 | Y | - | - | - | Y | - | - | - |

| Bigby & Craig, 2017 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fyffe & Raskin, 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - |

| Green et al., 1995 | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | Y | Y |

| Hardman & Clark, 2006 | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - |

| Heslop, 2005 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hughes & Walden, 1999 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jameson, 1998 | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | - | - |

| Mavropoulou, 2007 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Southby, 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tse et al., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - |

3.2.3 Aims, parameters and activities undertaken

The stated aims of the befriending interventions varied across the studies (see Table 4). Whilst some interventions appeared to focus primarily upon forming relationships and friendships (Hardman & Clark, 2006; Hughes & Walden, 1999), others aimed at increasing access to community resources and facilities by providing additional support to befriendees (Ali et al., 2021; Fyffe & Raskin, 2015; Heslop, 2005; Jameson, 1998). For example, in Fyffe and Raskin's (2015), p. 84) study, the befrienders are seen as acting as a ‘bridge to the resources and opportunities in the wider community’.

| Study | Stated aims of befriending activities | Expected frequency, duration or type of activity | Example activities undertaken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al., 2021 | To provide emotional support and to facilitate access to activities in the community | One hour, weekly; >50% of activities to be community-based | Visiting cafes/restaurants, walks, conversation at home. |

| Bigby & Craig, 2017 | n/a | n/a | Swimming, choir, coffee club, church friendship circle. |

| Fyffe & Raskin, 2015 | To experience a more inclusive lifestyle through the development of a social relationship | No specific requirements—expectations of flexibility in arrangements | Going to movies, antiques shopping, restaurants |

| Green et al., 1995 | n/a | Weekly; community-based activities, of mutual interest, engaged in as equals | Going out to eat, touring cathedrals, shopping, bowling, pool, basketball. |

| Hardman & Clark, 2006 | To enhance the lives of people with intellectual disabilities through one-to-one friendships with people without disabilities | Weekly contact; 2 or 3 one-to-one activities per month | Friendship activities: Phone calls, eating out/at home, watching movies out/at home, sports events, outdoor recreation. Teaching activities: social skills, transportation, job skills, personal finance. |

| Heslop, 2005 | To reduce social isolation and increase community participation; to provide a range of different activities and support for accessing local leisure facilities | n/a | Home-based activities—having meals, watching videos. Going out to movies, gym, bowling. |

| Hughes & Walden, 1999 | To form friendships and to practise skills in developing relationships | n/a | n/a |

| Jameson, 1998 | To build social relationships between [people] and enhance social integration; to get more involved in the community while sharing mutually satisfying activities | n/a | Eating together (out or at home), phone conversations, going to movies, shopping, walks, concerts/theatre, physical recreation. |

| Mavropoulou, 2007 | To improve the quality of life of people with ASD | Weekly | n/a |

| Southby, 2019 | n/a—Note that an inclusion criterion for the study was taking part in mainstream activities, not segregated or private setting activities | n/a | Visiting cafes/restaurants, shopping, tourist attractions, theatre, music performances, museums, bowling, golf |

| Tse et al., 2021 | n/a—Varied across services | n/a | Visiting cafes/restaurants, visiting parks/outdoor spaces, spending time indoors, art/creative activities, museum/ galleries, farm/zoo, cinema |

There is a lack of clear consensus in the terminology used across the 11 studies. Whilst terms are not necessarily used interchangeably, authors talk of social integration (Jameson, 1998), community participation (Heslop, 2005), quality of life (Mavropoulou, 2007), inclusion (Hardman & Clark, 2006), social inclusion (Heslop, 2005; Southby, 2019) and inclusive lifestyles (Fyffe & Raskin, 2015), without explicitly stating their definitions for each of these constructs. Whilst each intervention's aims appear to have been developed with consideration for the needs of the individuals involved and a desire to address these, the lack of common language makes it difficult to draw direct comparisons across studies. The concept of social inclusion appears to be central to many of these interventions. Simplican et al.'s (2015) ecological model defines social inclusion as an interaction between community participation and interpersonal relationships, which can differ in terms of scope, setting and depth. Whilst social inclusion now sits at the heart of many policies focused upon people with intellectual disabilities, it is often poorly defined and measured (Bigby, 2012). This review found that only 2 of the 11 studies explicitly mentioned social inclusion, and neither included a definition (Heslop, 2005; Southby, 2019).

The basic befriending intervention parameters (such as frequency of contact and activities undertaken) were similar across the 11 studies (see Table 4). Nine studies reported the befriending activities undertaken, showing a combination of home-based activities and community-based activities. Visiting cafes/restaurants, walking and going to the movies appeared most frequently as examples, though home-based activities such as having conversations at home, spending time indoors or watching videos, were also reported across several studies. Whether activities were home-based or community-based appeared to be influenced by the inclusion criteria for the study (note that Southby's eligibility criteria include taking part in mainstream activities rather than segregated or home-based activities), or by explicit prescription of community-based activity sessions by the scheme coordinators (Ali et al., 2021; Green et al., 1995). There was not sufficient detail to explore whether the characteristics of the external organisation supporting the befriending relationship influenced the mix of home-based or community-based activities undertaken.

3.3 Reported psychological and social outcomes of befriending

Key findings relating to the psychological and social outcomes of befriending interventions were collated from the 11 studies, compared and grouped into different outcome categories (see Table 5).

| Study | Befriendee outcomes | Befriender outcomes | Other | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community participation | Changing social networks | New experiences | Mood | Confidence and independence | Knowledge and experiences | Giving back | Expanded social communities | Broader impact | |

| Ali et al., 2021 | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bigby & Craig, 2017 | Y | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | Y | - |

| Fyffe & Raskin, 2015 | Y | Y | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y |

| Green et al., 1995 | - | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | - |

| Hardman & Clark, 2006 | Y | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - |

| Heslop, 2005 | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - |

| Hughes & Walden, 1999 | - | Y | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jameson, 1998 | - | - | - | - | - | - | Y | - | - |

| Mavropoulou, 2007 | - | - | - | Y | - | Y | - | - | - |

| Southby, 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tse et al., 2021 | - | - | Y | - | - | Y | Y | - | - |

3.3.1 Outcomes for befriendees

Community participation (social outcome)

Six studies noted specific outcomes around community participation. The quality ratings of the studies ranged from 0.85 to 0.95 (averaging 0.91). Two reported that befriendees benefitted from increased participation in community-based activities as a result of the partnership (Bigby & Craig, 2017; Fyffe & Raskin, 2015). Southby (2019) distinguished between activities undertaken as part of a collective group (e.g., with a team), and activities performed individually between a befriending pair (e.g., going to the cinema). He argued that whilst befriending may increase the number of activities carried out in community-based settings, the sense of inclusion may be lesser than in some ‘segregated’ settings where more collective activities are undertaken. Similarly, Heslop (2005) reported that fewer than a fifth of the activities identified in her study specifically increased social inclusion.

Two studies attempted to measure befriendees' perceptions of community participation. Hardman and Clark (2006) reported that 46% of befriendees surveyed felt more comfortable participating in the community following a befriending intervention. Though not a majority, the authors point to the fact that 74% of the befriendees already had friends without disabilities prior to the intervention, and thus may already have had prior opportunities for community participation (implying that they already felt quite comfortable in the community). The study had a quality appraisal score of 0.81, though for this data point the proportion of befriendees selecting ‘neutral’ or ‘disagree’ is not presented, so the authors' interpretation is hard to confirm. Ali et al.'s (2021) pilot RCT showed a positive shift in the means for social participation outcome measures for both control and intervention groups. The study scored highly (0.89) on the quantitative QualSyst measure, however, due to the small sample size changes were presented as descriptive statistics and not statistically analysed. Taken together, the findings suggest that befriending does lead to increased presence within the community, though the degree of ‘true’ social inclusivity may be more uncertain.

Changing social networks (social outcome)

Five studies reported changes to befriendees' social networks as an outcome of befriending (with quality ratings from 0.6 to 0.95, averaging 0.86). Three report positive changes relating to forming new friendships and increasing and diversifying social networks (Fyffe & Raskin, 2015; Hardman & Clark, 2006; Southby, 2019). However, two studies reported more mixed results. Hughes and Walden's (1999) intervention study found changes in network composition, with three of the four participants appearing to substitute existing network members for befriending volunteers over the course of the study and follow up. This study used descriptive quantitative measures of social network size, though it rated relatively poorly against the QualSyst criteria (scoring 0.6) with limitations noted in relation to study design, sample size and analytic methods. Bigby and Craig's (2017) study, with a stronger QualSyst score of 0.9, identified having a new friend as an outcome, but also noted some substitution within the befriendee's close network, with the befriendee's mother visiting less once the befriender was involved. These findings tentatively suggest that befriending may add new members to a befriendee's social network, but that this might be at the cost of existing members.

New experiences (social outcome)

Opportunity for befriendees to engage in new experiences was an outcome reported in three studies (all with QualSyst scores of 0.9). Bigby and Craig's (2017) case study reported that befriending enabled the befriendee to try new activities and join groups she may not otherwise have been able to (e.g., attending a choir). Southby (2019) reported that whilst befriending offered an opportunity to do new things, including educational or cultural activities, the activities undertaken were often repeated. ‘Casual’ leisure activities that the befriendee often also undertook with support workers (e.g., visiting cafes) seemed to be most commonly repeated, leading to concerns that the unique dynamics of a befriending relationship were not being fully taken advantage of. Tse et al. (2021) also noted that some befrienders found frequently repeated activities tedious. As shown in Table 4, the range of activities undertaken across the studies was broad, though there was considerable repetition of certain activities. Overall, the findings suggest that whilst befriending offers opportunities for new experiences, engaging in more familiar and known experiences is a common result.

Mood (psychological outcome)

Four studies reported an impact of befriending on the befriendees' mood. The quality of these studies was extremely varied and scores ranged from 0.2 to 0.9 (averaging 0.71). Ali et al.'s (2021) pilot RCT found that depression scores after 6 months were four points lower in the intervention group compared with the control group (equivalent to a moderate effect size). However, the pilot only matched six pairs in its intervention arm and was under powered. Southby's (2019) qualitative case study findings were that befriending activities supported individual wellbeing and promoted happiness. Of note, two studies reported negative effects on mood when the befriending relationship ended. Heslop (2005) recognised a need for services to focus on befriendees' emotional wellbeing, reporting that 12 of 14 interviewees who had experience with a previous befriender felt ‘sad, disappointed, angry and upset’ about the pairing coming to an end. In Mavropoulou (2007) study, the parents of befriendees noted breaks and endings as sources of anxiety and disappointment (though we note that the quality of this study was only rated as 0.2, with particular deficits against the methods and analysis criteria). Taken as a whole, the studies tentatively suggest both benefits and risks to mood.

Confidence and independence (psychological outcome)

Increased confidence and independence of befriendees were reported as outcomes in four studies, with appraisal ratings ranging from 0.81 to 0.95 (averaging 0.88). Southby (2019) reported that befriending helped promote individual independence (away from family and services) and improved befriendees' confidence and communication skills. Fyffe and Raskin (2015) suggested that even shorter matches increased confidence to build networks and have new experiences, and 44% of befriendees surveyed by Hardman and Clark (2006) felt more comfortable speaking up for themselves following befriending.

3.3.2 Outcomes for befrienders

Knowledge and experiences (psychosocial outcome)

Five studies reported that befriending enabled befrienders to gain new knowledge and experiences, including developing different perceptions of people with intellectual disabilities (Green et al., 1995). Eight out of 10 befrienders surveyed by Hardman and Clark (2006) reported having a more positive attitude about, and understanding of people with intellectual disabilities. The befriending relationship was also reported to offer new and different perspectives on matters (Tse et al., 2021) and opportunities to gain specific experiences to support future academic endeavours or employment (Mavropoulou, 2007; Southby, 2019; Tse et al., 2021). The studies had quality appraisal scores ranging from 0.2 to 0.9 (averaging 0.7).

Giving back (psychosocial outcome)

‘Giving back’ was reported as a key outcome of befriending in four studies, with quality ratings of 0.7–0.9 (averaging 0.83). This involved offering both practical help and emotional support (Tse et al., 2021). Green et al. (1995) identified that befrienders took on elder sibling roles offering opportunities for altruism, but also involving a sense of obligation. Southby (2019) noted that whilst befriending offered the opportunity to ‘give back’, negotiating the balance between friendship and a professional/service relationship was an ongoing challenge. Jameson (1998) reported that whilst befrienders ‘gave’ more in terms of concrete acts, 70% thought the level of reciprocity was equal in their befriending relationships. Overall, the findings suggest that befrienders value the opportunity to give back through befriending but that negotiating the actualities of each relationship can present challenges.

Expanded social communities (social outcome)

Three studies reported that befriending enabled befrienders to expand their own social networks or communities, with quality appraisal scores ranging from 0.9 to 0.95 (averaging 0.92). Fyffe and Raskin (2015) highlighted how befrienders make new friends, whilst Bigby and Craig (2017) and Southby (2019) noted that befrienders participate in new community groups and get a chance to do new things.

3.3.3 Outcomes for carers

Two papers reported outcomes for carers more broadly (with QualSyst scores of 0.9 and 0.95, averaging 0.93). Fyffe and Raskin (2015) recognised that befriending provided respite for family carers, though noted that this was usually shorter and less predictable than traditional respite breaks, whilst Southby (2019) highlighted the potential for existing family relationships to be disrupted by a befriendee becoming more empowered. Southby also considered the impact of befriending interventions upon residential service providers, noting that the presence of a befriender in the befriendee's social network reduced pressure to find stimulating activities for residents.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Key findings

This review aimed to synthesise the literature on the characteristics and outcomes of befriending interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities. Eleven studies were included, with various study designs and focuses. Befriending schemes employed similar recruitment and matching methods and aimed to foster friendships and increase community participation though approaches to fostering social inclusion differed between studies. Few interventions had strict parameters around frequency or duration of contact, though some did specify that activities should be community-based. Activities undertaken were broad ranging, including home- and community-based activities, with casual leisure activities such as visiting cafes/restaurants, walking or going to the movies most popular.

For befriendees, the most frequently reported outcomes were increased participation in the community and making new friends, suggesting the primary aims of befriending services are often being achieved. However, the degree of true social inclusion fostered by the activities undertaken was questioned, and some substitution of befrienders for existing social network members was reported. Similarly, whilst befriending can positively affect a befriendee's mood, it also presents a risk of negatively affecting emotional wellbeing, particularly where the ending of a befriending relationship is not adequately managed.

Befriending appears to lead to increased confidence and independence for befriendees, which may contribute to the mixed findings on new experiences also reported, with befriendees feeling more confident contributing to decision making and voicing their preferences for doing familiar, repeated activities rather than always striving for novel experiences. Information on decision making in befriending relationships is not commonly reported so this link remains unclear. This review's findings on befriendee outcomes support existing research with mental health populations which suggest befriending promotes community participation (Mitchell & Pistrang, 2011) and increases befriendees' number of social contacts (Priebe et al., 2020).

For befrienders, whilst certain challenges such as negotiating the friendship/professional relationship balance are reported, individual outcomes seem more universally positive overall. Befrienders gained knowledge and new experiences, felt a sense of giving back and expanded their social communities through taking part in befriending. This echoes the experiences reported by studies looking at volunteer experiences of mental health befriending (Cassidy et al., 2019; Toner et al., 2018) and may highlight the power dynamic between befriendee (‘deemed likely to benefit’ from befriending) and befriender who acts as a volunteer, therefore having more control over the experience and the relationship. Befriending has a broader impact upon carers, providing respite for family carers and reducing pressure on other services to organise activities.

4.2 Limitations of the evidence base

Despite the popularity of befriending schemes, this systematic review (with its intentionally broad search terms) only identified 11 studies. Similar to reviews of befriending in other populations (Siette et al., 2017) and of other interventions promoting social participation for people with intellectual disabilities (Howarth et al., 2016), this review suggests that befriending does have positive outcomes but that a stronger evidence base is required to inform policy and practice. On an individual basis, the majority of the 11 studies reviewed appeared of relatively high quality, with the qualitative and quantitative studies scoring QualSyst averages of 0.75 and 0.82, respectively. However, the studies were methodologically diverse and mostly qualitative and exploratory in nature, with those utilising quantitative approaches limited in their data analysis due to small sample sizes. Another key limitation of the evidence base is the limited input of people with intellectual disabilities into study design and conduct. Ali et al.'s RCT protocol (Ali et al., 2020) described consultation with befriending scheme participants with and without intellectual disabilities during planning stages, and plans to engage a ‘public and patient involvement’ group to advise on materials, attend study management meetings and contribute to data collection and dissemination. Heslop (2005) also acknowledged the contribution of an advisory group to her study, though the extent of their involvement was not explicated. None of the other studies identified in this review mentioned any input from people with intellectual disabilities. Lack of direct input from people with intellectual disabilities into the research questions, study designs or data collection and analysis stages, leads to a lack of representation and an imbalance of power in the conduct of research.

4.3 Limitations of the current review

Whilst the last author independently screened full text articles and rated a third of the studies using the quality appraisal tool, the rest of the review was conducted by the first author, increasing the risk of bias in the synthesis and interpretation of results. Though no English language filter was applied on database searches, only search terms in English were used, and grey literature was excluded which may have reduced the comprehensiveness of the review. Whilst the search terms used were intentionally broad this may have increased heterogeneity and the complexity of the narrative synthesis.

4.4 Implications for future research and practice

This review highlights the limited body of evidence pertaining to the effectiveness and impact of befriending interventions for people with intellectual disabilities. Following on from Ali et al.'s (2021) pilot RCT, future studies could employ broader eligibility criteria or focus upon a broader range of outcomes. In practice, UK-based befriending services have increased outcome measure collection and evaluation over the past 15 years (Tse et al., 2021). Extending this by use of standardised, validated measures across befriending services could create opportunities for robust longitudinal studies. Tracking the long-term effects of befriending, (particularly for those befriendees who have experienced the endings of befriending relationships) is vital.

This review further indicates a need for clarity around social network substitution and whether expanding social networks may come at the expense of important existing relationships. Work into understanding the potential value of diversifying existing network composition, rather than simply increasing network size would be valuable. The extent to which community participation through befriending equates to or supports social inclusion should also be further explored, with reference to the importance of setting (e.g., mainstream community versus disability specific versus private), degree of involvement in any given activity, and the degree to which interpersonal relationships are necessary to facilitate this. There is a need for further exploratory analysis of the mechanisms of change and optimal methods of delivery of befriending in this population, and for more research that hears the voices of people with intellectual disabilities directly, both as participants and as contributors to research design and conduct. In including these voices directly, research could consider what adults with intellectual disabilities themselves prioritise in terms of the desired outcomes of any befriending intervention and how this links with understandings of social inclusion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Open access publishing facilitated by University College London's transformative agreement with Wiley.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

I declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. I, corresponding author on behalf of all contributing authors, hereby declare that the information given in this disclosure is true and complete to the best of my knowledge and belief.

APPENDIX A

| Category | Type of term | Terms used |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual disabilities and/or autism | Subject headings | PsycINFO: Learning disabilities/or autism spectrum disorders/ MedLine: learning disabilities/or intellectual disability/ autism spectrum disorder/or asperger syndrome/or autistic disorder/ Web of Science: No subject headings |

| Search terms | intellectual* disab* or developmental* disab* or learning disab* or intellectual development disorder or IDD or mental* retard* or mental* handicap* or intellectual* impair* or autis* or asperger* |

|

| Befriending | Subject headings | PsycINFO: Friendship/ MedLine: Friends/ Web of Science: No subject headings |

| Search terms | befriend* or buddy or buddies or friend* or companion* or lay helper or compeer or peer support* or peer relation* or mentor* or unpaid care* or informal care* or voluntary care* or natural* contact* or natural* support* or supported sociali?ation or peer assistance or community support or nonprofessional volunteer or nonprofessional worker* or citizen participation or civic participation or community participation or social networks or social network | |

| Adults | Search terms | NOT ((adolescen* or school or child*) not adult*) |

APPENDIX B

| Item number | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Qualitative checklist | |

| 1 | Question/objective sufficiently described? |

| 2 | Study design evident and appropriate? |

| 3 | Context for the study clear? |

| 4 | Connection to a theoretical framework/wider body of knowledge? |

| 5 | Sampling strategy described, relevant and justified? |

| 6 | Data collection methods clearly described and systematic? |

| 7 | Data analysis clearly described, complete and systematic? |

| 8 | Use of verification procedure(s) to establish credibility? |

| 9 | Conclusions supported by the results? |

| 10 | Reflexivity of the account? |

| Quantitative checklist | |

| 1 | Question/objective sufficiently described? |

| 2 | Study design evident and appropriate? |

| 3 | Method of subject selection described and appropriate? |

| 4 | Subject characteristics sufficiently described? |

| 5 | Random allocation to treatment group described (if possible)? |

| 6 | Blinding of investigators reported (if possible)? |

| 7 | Blinding of subjects reported (if possible)? |

| 8 | Outcome/exposure measures well defined and robust to bias? Means of assessment reported? |

| 9 | Sample size appropriate? |

| 10 | Analysis described and appropriate? |

| 11 | Some estimate of variance reported for main results/outcomes? |

| 12 | Controlled for confounding? |

| 13 | Results reported in sufficient detail |

| 14 | Results support conclusions? |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.