Sturgeon meat and caviar production: Global update 2017

Summary

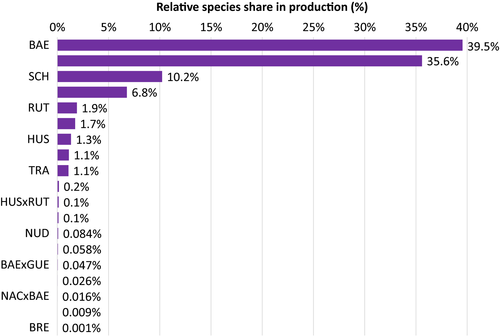

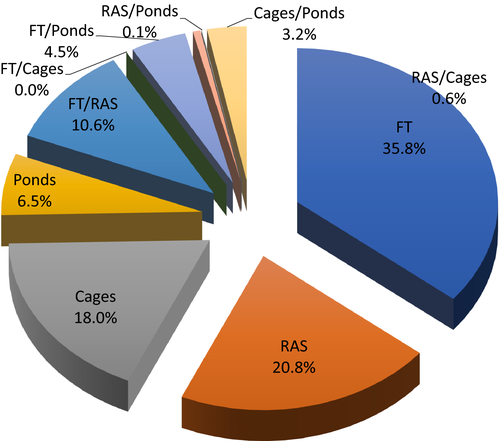

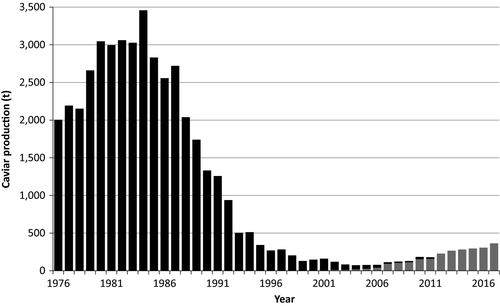

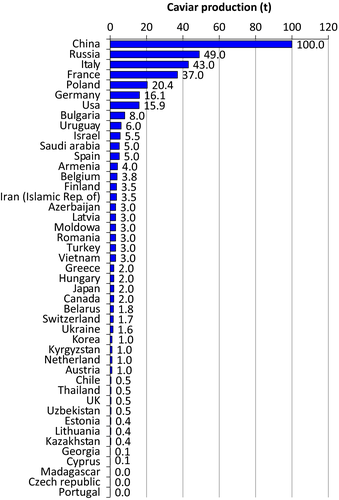

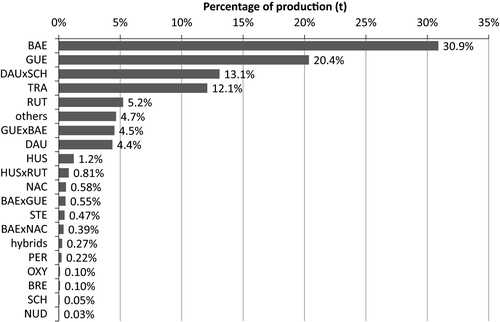

This paper presents an update on the global sturgeon and caviar production until 2017, attempting to continue previous efforts on summarizing the global trends in these markets. For the current update, an expanded data base was derived from questionnaires sent to 86 regional contacts in 46 countries, mostly farmers or scientists, and personal interviews. A total of 2,329 commercial sturgeon farms were recorded by 2017 globally, which represented an increase by 7% compared to 2016. Of these farms 54% were located in China, followed by Russia (24%), the Middle East (8%), the Far East (7%) and Europe (6%). Among the rearing technologies flow-through (FT) systems (36%) were most common, followed by recirculation aquaculture systems (RAS) (21%), cages (18%), mix FT/RAS (11%), and ponds (6%). In total the aquaculture sturgeon biomass production peaked at about 129,608 t in the year 2015, with a decline to 119,979 t in 2016, and to 102,327 t in 2017. China contributed about 79,638 t to the overall production in 2017, followed by Russia (6,800 t), Armenia (6,000 t), Iran (2,514 t), and 52 other countries with less than 1,000 t each. This production exceeded the fishery harvest during the 1970–1980s by more than four times. Of the 25 species of Acipenseridae, 13 pure species and four hybrids were farmed for meat with Acipenser baerii dominating production in 2016 with a share of 39.5%, followed by the two hybrids, Huso dauricus × Acipenser schrenckii and A. baerii × A. schrenckii (35.6%), as well as A. schrenckii (10.2%). Global caviar production increased during the last years and the production for the year 2017 amounted to approximately 364 t. China contributed more than 100 t to the overall production in 2017, followed by Russia (49 t), Italy (43 t), France (37 t) and diverse other countries. The species composition in caviar production in 2016 was dominated by A. baerii (31% of the total volume), followed by Acipenser gueldenstaedtii (20%), the hybrid H. dauricus × A. schrenckii (13%), and Acipenser transmontanus (12%), while other species jointly contributed 24% to the overall yield. The trends of sturgeon meat and caviar productions of the last 5 years and the forecasts for the future suggest a short-term scenario in which the demand remains lower than the supply. In order to absorb the growing production, the market will have to be expanded by targeting new market segments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sturgeons—and especially the commercial species of the Black and Caspian Seas—have undergone a dramatic decline mainly exhibited in the 1990 and 2000s (Figure 1). This was caused mainly by legal and illegal overfishing, habitat deterioration, river fragmentation including damming and pollution. These species are now protected in all range states with legal fisheries for limited quantities in only some countries (e.g., Russia, Canada, USA) while being listed in Annex II and I of the CITES regulations. Despite the increased protection efforts, their status continuously decreased (see IUCN, 2018; Bronzi & Rosenthal, 2014). Since the end of the 20th century, sturgeon farming started to partially substitute the production from fisheries. With some years delay, also farmed caviar started to enter the market, increasingly substituting wild caviar. Although some market sectors were still demanding products from wild sources, gradually the caviar from farmed sources gained similar acceptance as the product from wild origin was no longer available and quality improvements became noticeable.

Trends of the global sturgeon and caviar production and trade have repeatedly been presented since the 1990s (Bronzi & Rosenthal, 2014; Bronzi, Rosenthal, Arlati, & Williot, 1999; Bronzi, Rosenthal, & Gessner, 2011; Williot, Bronzi, & Arlati, 1993; Williot, Nonnotte, & Chebanov, 2018). In this paper, we present the most recent update on the world sturgeon and caviar production until the end of 2017 with a major focus on the period 2013–2017. During this period, new farms were established in traditional sturgeon farming countries as well as in countries which have previously not been involved in sturgeon farming (e.g., Madagascar).

This survey focuses on the production of the family Acipenseridae, deliberately excluding paddlefish (Polyodontidae), since it is not included in the Codex Alimentarius as a species producing sturgeon caviar. An overview on Paddlefish in aquaculture and its introductions can be found in Jarić et al. (2018).

The data provided in this survey frequently differ from other reports, mainly referring to official statistics and reports (FAO FishstatJ, EUMOFA, 2018, FEAP, 2017). Nevertheless, because of successive and detailed data collection over more than a decade, the data presented here represent the global scenario of sturgeon and caviar production accurately. In order to improve the quality of the data, we would highly appreciate constructive criticism as well as comments or corrections as well as open collaborations.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

The production data presented are mainly based on information provided by farmers or scientists in response to a questionnaire and subsequent personal interviews, so the data were compiled mostly via individual e-mail messages. The data included names and locations, the main characteristics of the facility (sturgeon farm for meat and/or caviar, flow-through [FT] systems, recirculation aquaculture systems [RAS], cages, ponds or a mix of culture facilities). Further, the survey requested data on meat and caviar productions for the current year as well as forecasts for 4 years into the future. In 2016, we also asked for information on the relative share of different species reared for meat and caviar in the facilities. The participants were asked to provide information also for other farms or data on the respective national/regional production. In some cases, we relied on production figures from colleagues locally involved in sturgeon aquaculture research or management as these persons had the best insight into the status of the industry. For China and Russia, due to the large numbers of farms, one expert per country collected the data for all the farms in these two countries. The same procedure was carried out also for other countries (e.g., USA) because of privacy requests from the farmers. When this survey attempt did not yield reliable or any data at all, we used official data (FAO, 2011). As a last resort, some production data were obtained from various sources on the internet, provided that the information obtained was plausible. When no data were made accessible for a given period, we kept a conservative approach, using an average value of the last 3 years reported. For the forecasts of productions, we used the same approach, asking each farmer or local experts to provide us their expected production level in future years based on the sturgeon stocks they have in their plants or based on regional or national development plans wherever they existed.

Taking 2017 as an example, individual personalized e-mail messages were sent to 86 farmers and scientists in 46 of the 56 countries known or supposed (internet news) to rear sturgeons since no contacts were available to us for 10 countries. We received responses from 34 countries, with different levels of detail of information.

Of the 22 countries remaining with little to no information being provided, production data from FAO statistics (FAO, 2011) were used for 12 countries. From the 10 countries left to cover, only five are certainly rearing sturgeons, even in relatively small quantities, but data scarcely became available through internet information. As a result, reliable production data were available for 46 out of 56 countries, representing the 82% of the countries involved in the global sturgeon production. For the other parameters (species reared, rearing technologies) the information basis is reported in the respective paragraphs.

To collect elements on the caviar market scenario perceived, a questionnaire was sent to 100 producers and traders asking opinions on their target groups, customers and their ages, the reasons for buying or not buying caviar, the future market segmentation, the place the customers use to buy caviar, the image their company have or would like to have, the reasonable wholesale and retail prices, the most important aspects for the success in caviar business, the main problem affecting caviar market.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Global sturgeon biomass production

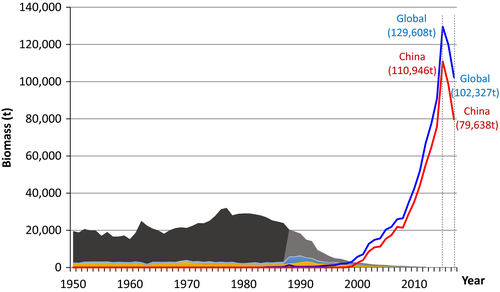

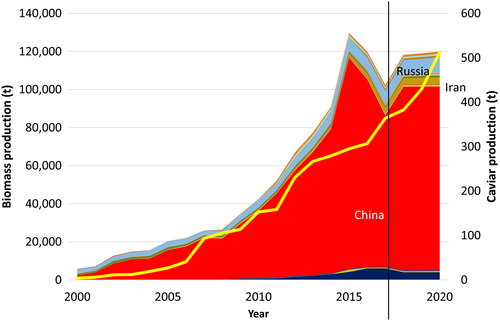

The global sturgeon biomass production (t) from fisheries during the period 1950–2011 (FAO FishtatJ) and the estimated productions from sturgeon aquaculture until the year 2017 are presented (Figure 1) based mainly upon the survey results. In total, the aquaculture biomass production peaked with some 129,608 t in the year 2015, but declined slightly to 119,979 t in 2016 and to 102,327 t in 2017.

Overall, it can be noted that in approx. 33 years, from 1984 when the first production data were reported by FAO, the estimated aquaculture production of sturgeon meat exceeded the high yields obtained from the fishery during the 1970–1980s by more than four times. A part of these biomass production figures represented the carcasses only because these fish have also been used for caviar production. No correction factor was applied to recalculate live weight due to differences in reported data with regard to commodities.

From 2013 onward, the annual global meat production increased, compared to the respective previous year, by 18.0% in 2014 and by 43% in 2015. In 2016, a decrease by about 7% compared to 2015 followed, and again in 2017 a decline about 15% was recorded compared to 2016.

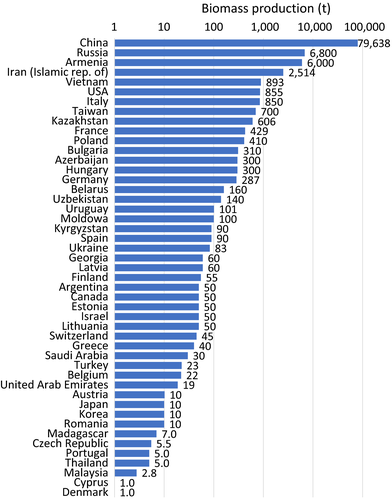

The estimated biomass production data per country in the year 2017 (Figure 2) reveals a certain underestimation of the global amount originates from incomplete or partial data deficient statistics from some countries. For example, in South Korea according to internal information 57 farms with more than 480,000 animals in stock were operational in 2014. Therefore, some continuous output on the market would be expected. The same holds true for Japan with 35 farms. In both cases, production data were unavailable. No information was made available for North Korea either, which is known to produce sturgeons. Likewise, from Moldavia limited information was available stating the onset of beluga caviar production in addition to the previous production of hybrid, sterlet and Acipenser gueldenstaedtii caviar but no data on production figures were obtained. UK farmers never answered to the questionnaire. However, the missing data most likely comprise a minor fraction of the global total.

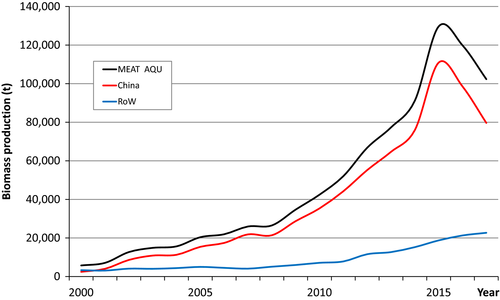

With 79,638 tonnes in 2017, the Chinese production represented approx. 78% of the global production, followed by Russia with 6,800 t (6.6%), Armenia with 6,000 t (5.9%), and Iran with 2,514 t (2.5%). In the case of Armenia, the output listed was exceptional because of a huge sale of sturgeons due to the bankruptcy of a company. The decline in the production of China was associated with the new governmental environmental protection regulations, widely prohibiting cage culture (CC) in inland waters. Since a major share of this production had to be relocated to land-based farms, males and females not used for caviar production were marketed for meat in 2015. Consequently, in the following years the Chinese sturgeon output was lowered compared to the previous year. From an assessment of the world production between 2000 and 2016 (Figure 3) the decisive role of China becomes evident.

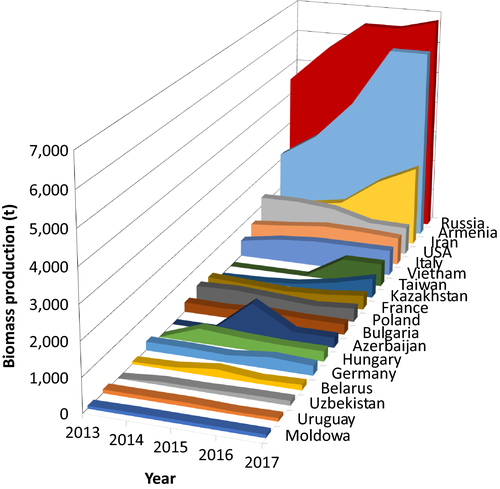

The 5 year trend, 2013–2017, of sturgeon production in countries with an individual yield of more than 100 t in 2017, without the Chinese production (Figure 4) allows to more clearly determine the differences between these countries and the respective trends of their production development. It seems especially noteworthy that the recent increase in production in several countries reflects the manifestation of the long-term strategic development and the capacities installed have the potential to increase the output in the coming years further.

3.2 Species farmed for meat production

The data on the relative share in the production for the different sturgeon species in 2016 revealed that out of the 25 species of Acipenseridae, 12 pure species and six hybrids had a major share in the meat production (Figure 5). Of these, Acipenser baerii was the dominating species with 39.5% of the total production reported, followed by the two hybrids (Huso dauricus × Acipenser schrenckii and A. baerii × A. schrenckii) (35.6%), A. schrenckii (10.2%), while the share of the other species reached less than 15% all together. Despite the lack of species related production data in some reports, the data comprised 116,324 t or approximately 97% of the global sturgeon production for that year.

3.3 Rearing facilites

In the last five years production expanded in traditional sturgeon farming countries like Russia and Iran as well as in some countries which have previously not been involved in sturgeon farming, while some of the existing companies collapsed. For this assessment both farms rearing sturgeon only and farms also rearing other fish species were considered. The global total number of sturgeon farms reached 2,329 plants in 2017. This value systematically underestimates the number of facilities rearing sturgeons because both the small farms rearing less than a few tonnes, as well as the missing data from some 10 countries, were not included in this dataset. The location of the plants (Figure 6) are provided with exception of China and Russia, where just the respective provinces with sturgeon farms present are provided. China with 1,254 farms (2016 data) represented 53.8% of the world total, followed by Russia (555, 23.9%), the Middle East area (181, 7.8%), Far East (168, 7.2%) and Europe (143, 6.1%). A new farm beyond the natural range of the species was recently established on the island of La Reunion (France) (yellow circled dot), and a farming trial is under way in Australia (circled exclamation mark).

3.4 Farming technologies

Sturgeon aquaculture techniques do not differ substantially from farming approaches for other fish species and applies technologies such as FT systems, CC, various pond systems (PS) either stagnant or FT, and Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS). Throughout the production cycle, several companies used various combinations of rearing technologies. The data given for the year 2016, provided a good overview for 1,959 plants, representing 90.4% of the total 2,168 farms identified in the survey for that year. The relative share of rearing technologies by farms (Figure 7) revealed that FT systems (36% of the total) were the most commonly applied technology in sturgeon farming. The reason for this was partly due to the fact that in some countries sturgeons gradually substituted commonly cultured species with less value on the markets (like trout and eel). Recirculating Aquaculture Systems with 21% of the farming systems have gained ground and succeed mainly in countries with limited water resources, high environmental emission standards or unfavourable temperatures. Open net cage culture represented 18% of the production facilities were employed worldwide, mainly in reservoirs, for instance in Vietnam and China. In China this system still represented 24% of the farms in operation in 2016. Decreasing water quality, high seasonal temperatures in some shallow lakes and primarily the new environmental policy in China, implemented in 2015, should have practically eliminated this system from the Chinese inland waters. Combined facilities utilizing both FT and RAS systems represented 11%, while sturgeon farming in ponds accounts only for 6.5% of the total facilities where often it replaced carp species in culture, for instance in Central and Western Europe countries.

3.5 Global caviar production

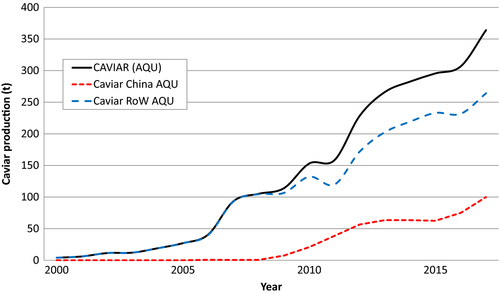

Global caviar production of aquaculture origin has progressively increased during the last 15 years and is estimated in 2017 to amount to 364 t. This figure probably is underestimated due to information deficits for some countries of origin. Based on past experience we suggest that this quantity could be 10–20 t higher globally.

The global caviar production (t) from fisheries (1976–2011, FAO, 2011 statistics), and the data for aquaculture production (1991–2017, this study) reveals that farmed caviar production has not shown a comparable increase as the sturgeon meat production (Figure 8). The global aquaculture output after 25 years of development remained at approx. 10% of the caviar production obtained from fisheries during the 1980’s. This difference between the trends in sturgeon meat and caviar output is mainly due to the huge Chinese production for sturgeon meat predominantly sold for human consumption, using fish of relatively small sizes (e.g., 750–1,000 g: “one fish, one dish”). Thus, these fish were not grown to maturity. This explains the discrepancy between the role of the Chinese production in meat and caviar in 2017 with a share in the global caviar production of 27% compared to 78% of sturgeon meat production (Figure 9).

The global production of caviar over the last 17 years (Figure 10) clearly shows that the Chinese share and its development over time differed markedly from the global production. The global increase was generated mostly by a rising caviar production in the established production countries and by newcomers on the markets, with more countries that started caviar production during the last 10 years.

3.6 Species used for caviar production

The commercial value of caviar largely depends upon the sturgeon species, but also to the species-specific time needed to reach maturity and thus the length of farming before the eggs can be harvested. These factors have relevance also in terms of the choice of the species to rear. Additionally, the species-specific bio-technological difficulties and requirements for rearing contributed to the decision for the species for production. This selection contributed to the difference between the species reared for caviar and reared for meat.

The most important sturgeon species reared for caviar production in 2016 was A. baerii accounting for 31% of production, followed by A. gueldenstaedtii (20.4%), the hybrid H. dauricus × A. schrenckii (13.1%), Acipenser transmontanus (12.1%), and Acipenser ruthenus (5.2%), while other species contribute 45% to the overall yield (Figure 11). Here again the quantities allocated did not cover the entire global production, but comprising approximately 84.1% of the total output, the data can be considered representative.

3.7 Production forecasts

Forecasts of meat and caviar production were also estimated on the basis of the information given mainly by farmers. Since not all were able to provide plausible estimates, while others did not make any commitment to a forecast, these were considered with a “conservative approach”. For example, the Chinese production was maintained at the same level reached in 2016, despite the reduction of the meat output and a huge increase of caviar production in 2017. As a result, the global meat production was estimated unlikely to change substantially during the next years and will remain around 110,000–120,000 t. Caviar production, based upon the information on the abundance of maturing fish in the stocks and the increasing share of ovulated eggs in the production of caviar, was expected to increase, reaching the total amount of about 500 t in 2020 (Figure 12). The feasibility of these forecasts obviously depends upon the market capacity and the choice of the producers. For the future these quantities could be underestimated, because the trend in the development of sturgeon culture in the past years in Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine and all other countries of the former USSR, allows to forecast an increase in meat and caviar production in the future. In fact, the number and weights of sturgeon females used in production of ovulated caviar has significantly increased and we can expect a significant increase in caviar production, both ovulated and traditional. Also, as a consequence of the recent legal permission to breed additional sturgeon species than Siberian sturgeon in France, fertilized eggs of other species have been imported and, as a result an increase in the rearing of Persian, Russian, Stellate, and other sturgeon species can be predicted which will result in an increased production of caviar.

3.8 Caviar market analysis

Caviar producers had a period of “golden years” in the first 15 years after the appearance of farmed caviar on the market, while at the same time legal wild caviar was becoming rare or unavailable and the prices increased dramatically. Farmed caviar was limited in supply, with prices following those of caviar from wild origin. Furthermore, during this period quality deficiencies were accepted due to low supply on the market. This period was followed by a time (approx. 3 years) that was characterized by a drastic increase in the aquaculture production, leading to the appearance of caviar on the market from more species and from different sources. Yet the prices were still stable, but international trade was increasing. In the subsequent 4–5 years, further increases in aquaculture production in additional countries were noted. However, the simultaneous lack of adequate market growth had led to an excess in supplies and a reduction in prices. The most recent scenario is characterized by a further increase of the production with a subsequent reduction in prices and profitability. Which will likely result in a reduction of the number of producers. The future of caviar trade may mainly be determined by demand-driven price structures, with a market diversification according to different products and prices. The onset of the different phases varied to some degree between countries, depending upon the internal production and the local demand as well as the marketing strategies of the producers.

A newly evolving “mass market” could be established or rather be re-established serving large numbers of consumers of a wide income range with an attractive product, matching their budget. This would require to increasingly utilize specialized supermarkets or even discounter chains as vendors, as was successfully practised in the late 1980 and early 1990. These markets will be mainly seasonal, as a most of the caviar is sold in festive seasons such as Easter, Christmas and increasingly at Chinese New Year. The traditional expensive luxury market will persist at a fairly modest level since increasing wealth in some regions of the world will lead to the habit to consume “exotic” food types in a larger style. Here, also the diversification with regard to species and to processing technology (traditional vs. ovulated caviar) can come into play to further enhance this development. In addition, more effort is required by the industry to inform a wider consumer group of the qualities of the produce and of the sustainability of the production.

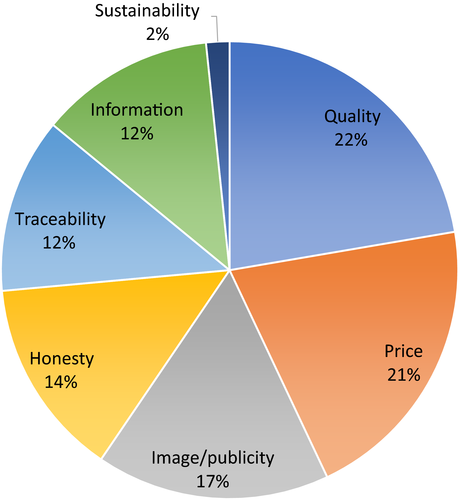

The 100 questionnaires sent yielded 36 answers from 18 countries. Based upon these responses, it was noted that product quality is considered to be the most important factor for success in the established caviar markets (Figure 13). This is further amplified by adequate pricing and the company image.

Private customers and mass retailers seem to be the most important customers at present, followed by repackers and airlines. Obviously, these results are extremely variable between producers, representing specific marketing approaches. When the target group of consumers is considered, the age of the customers is still advanced (>60 years of age). Therefore, the expansion into other segments of consumer groups seems to be one of the main target areas for future market development and to secure the future consumers. Also the lack of sufficiently comprehensible information on the product providing substantial and relevant information on the quality and characteristics of the product, allowing customers to distinguish between products and make an educated choice is hampering the development of markets. Furthermore, the erosion of the market by numerous imitations, copying the image and packaging of sturgeon caviar while being sold for a fragment of the price continues with a production of approx. 10,000 t in 2017 (FAO, 2018), which is more than 33 times the total caviar production of that year. This indicates that the image of caviar sells beyond the classic markets but that the price drives the acceptance to a larger degree than the quality.

While in the future the production is expected to increase, the producers expect the retail prices to subsequently decrease to an average of 1,000 €/kg severely reducing the chances to attract new consumer groups to the product. Caviar is still perceived in the collective image of most customers as something exclusive for rich people, which in fact still consider eating caviar a status symbol and a health food. Any market expansion will be influenced by emotional forces that are intangible and marketing will be the most important driver for conquering new market segments for caviar (Sicuro, 2018).

4 CONCLUSIONS

The reported data and the proposed global scenario can be considered fairly reliable, even if they are by no means complete for the reasons already described. Some challenges in comparing public production statistics are associated to inconsistent reporting, while some production figures reflect the true output of the respective year, other statistics refer to the quantities officially sold during the year of reporting. One of the main potential errors in data collection are associated to the trade patterns for live sturgeons. Fish are commonly sold from one farm to another often crossing country borders. This process can be repeated several times which increases the risk that that these fish being counted twice or multiple times despite the fact that only the biomass increase per year must be considered as production. This issue is reflected also in the CITES and IUCN discussions on the identification and labelling of origin of sturgeon produce (CITES 29th meeting of the Animals Committee, Geneva [Switzerland], 18–22 July 2017).

The trends of sturgeon meat and caviar production 2013–2017 and the forecasts for the future suggest a short-term scenario in which the demand remains lower than the offer. While the market for sturgeon meat is well developed in a variety of countries like China, Russia, and Iran, but is still lacks market acceptance and penetration in European countries where sturgeon meat is mostly considered a side-line of production. Here market development could provide room for expansion.

Globally the caviar market neither has fully revived the main outlets that were instrumental for the consumption in the 1980s such as cruise lines and airlines. Neither has it reached out into new categories of customers, nor having been able to expand consumption by wealthier communities. Over the past 5 years the market demand for caviar seems not to have increased sufficiently; meanwhile the availability of cultured product did grow, with the result that wholesale prices have generally declined. China exported caviar of good accepted quality to Europe and Russia, but the internal Chinese market has not yet seen a substantial increase in caviar consumption. Some producers seem to have difficulties to enter into new markets, as it takes time to develop a broader customer market.

Caviar remains a luxury item, expensive at retail market even though the wholesale prices have decreased to sometimes very low levels (about 250 €/kg), although some signs of expansion have begun to appear regionally. Market development for Caviar is currently ongoing locally, for instance in China (W. Qiwei, personal communication) to establish new consumer groups. The forecast for the coming years suggests a scenario in which the demand will still remain lower than the supply.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This survey would not have been possible without the kind collaboration of farmers, scientists and sturgeon friends from all around the world, who have been repeatedly asked to help collecting data in all these years. Being unable to include all the names of contributors as co-authors on the front page, we would like to mention them here in the acknowledgement in alphabetical order: Nikolai Barulin, Yigal Ben Tzvi, Philippe Benoit, Billzhangzhu, Olivier Brunel, Cornel Ceapa, Mia Cambré, Sandro Cancellieri, Daniel Conijeski, Delphyne Dabezies, Celine Daffos, Carlo Dalla Rosa, Bastien Debeuf, Laurent Deverlanges, Le Anh Duc, Thomas Friedrich, Sergio Giovannini, Natalia Gorkunova, Justin Henry, Martin Hochleithner, Carin Holmqvist, Abdolhay Hossein, Alan Jones, Deborah Keane, Angela Köhler, Ryszard Kolman, Vladimir Kostousov, Antony Lakomiak, Sooncheol Lee, Otomar Linhart, Facundo Marquez, Stefano Marturano, Devrim Memis, Henryk Mokrzycki, Mohammad Pourkazemi, Anna Pyc, Giancarlo Ravagnan, Arpad Rideg, Laurent Sabeau, Iveta Sarova, Paul Daniel Sindilariu, Radu Suciu, Saodat Sultanova, Thi Thanh Tam, Sergei Tracuks, Béla Urbanyi, Stefania Vannuccini, Laszlo Varadi, Tetiana Yakolieva, Gwang Seok Yoon, Renzo Zanin, Mark Zaslavsky, Paulo Pedro Zaragoza, Yuanchao Zou. I apologize if I forgot someone.