Subcutaneous Mass Aspirate from a Dog

Case Presentation

A 13-year-old spayed female mixed-breed dog was referred to the oncology service at Kansas State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital with a history of 2 subcutaneous masses, one located in the right scapular region and one on the caudal ventral abdomen. The masses had been aspirated previously and identified as neo-plasia by a pathologist at a reference laboratory. In the pathology report it was noted that the scapular aspirate had features of an epithelial tumor, whereas the caudal ventral abdominal mass aspirate had features of a sarcoma.

On physical examination, the dog was alert and responsive, with hyphema in the left eye and a skin tag near the left eye. Diagnostic evaluation included a CBC, blood chemistry profile, urinalysis, thoracic radiographs, body mapping, multiple fine-needle aspirates (Figure 1), and a true-cut biopsy of the mass on the ventral abdomen. The CBC results were within normal limits. The chemistry results revealed a mild increase in urea nitrogen (40 mg/dL, reference range 8–30 mg/dL) and creatinine (1.9 mg/dL, reference range 0.5–1.4 mg/dL) concentrations, which in the context of a urine specific gravity of 1.030 were explained as prerenal azotemia. Thoracic radiographs revealed evidence of early metastatic disease with multiple nodules in the lung fields. Body mapping revealed 13 cutaneous nodules, including the 2 previously described subcutaneous masses, which ranged from 4×2×4 mm to 30×40×20 mm.

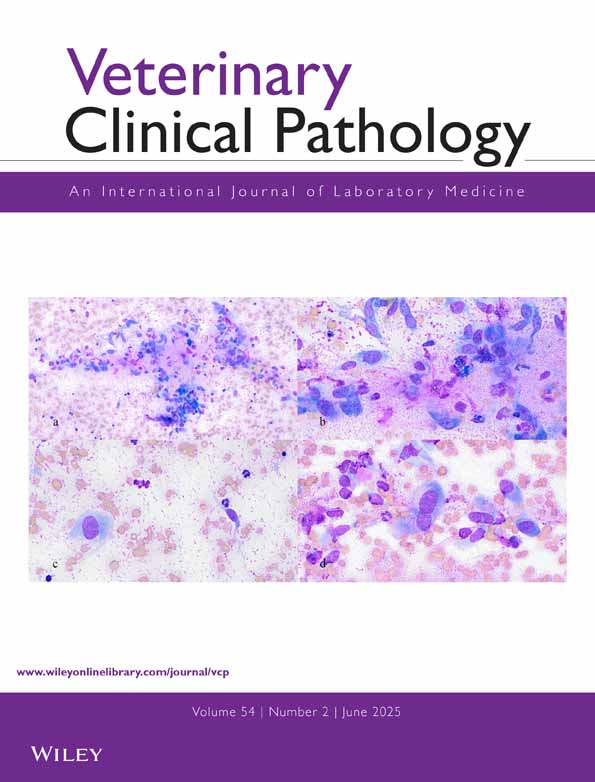

Fine-needle aspirate of a subcutaneous mass on the caudal ventral abdomen of a dog with multiple masses (A–D). Diff Quik, ×200.

Cytologic Interpretation

Cytologic results of all of lesions were similar to those in the caudal ventral abdominal mass specimen. The aspirates contained numerous cohesive epithelioid neoplastic cells loosely arranged in sheets or nests or as individual cells (Figure 1A). Occasional cells with primitive intracytoplasmic lumens contained pink material and sometimes were eythrophagocytic (Figure 1A, arrow). Rarely, individual cells were oriented around interlacing strands of eosinophilic matrix material (Figure 1B). RBCs and neutrophils were abundant. Small clusters of cells appeared vasoformative and sometimes formed microacinar structures surrounding a central zone of pink material (Figure 1C, arrow).

Individual cells were round to oval and had high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios, with eccentrically displaced, large, round to oval nuclei and a variable amount of pale basophilic cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic borders were distinct to indistinct. Rare spindle-shaped cells were noted. Anisokaryosis was moderate to marked, with occasional karyomegaly and prominent angular nucle-oli. Nuclear chromatin was finely stippled to coarse. Mitotic figures were common and sometimes bizarre. Several tumor cells appeared to resemble signet-rings, containing a distinct round or spheric density that stained pink (Figure 1A). In some cells, the cytoplasmic material contained neutrophils or RBCs and appeared to be surrounded by a thin membrane (Figure 1D). Few macrophages with abundant vacuoles and blue-black pigment granules were noted. Based on the location of the mass, its likely association with a mammary gland, and the cytologic appearance, a tentative diagnosis was made of an epithelial tumor, suspicious for mixed mammary carcinoma.

Histopathologic Interpretation

Histologic sections of the true-cut biopsy specimen showed a highly cellular neoplastic mass bordered on the deep margin by skeletal muscle. The loosely cohesive cells were arranged in large sheets and nests dissected by dense fibrovascular stroma. In less dense areas, irregular interlacing channels separated the cells (Figure 2A). Channels were often collapsed, whereas others contained RBCs. The neoplastic cells formed the lining of these channels. The cells were oval to polygonal, with indistinct cell borders, amphophilic to lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, and oval nuclei with coarse chromatin and 1 to 3 nucleoli. Several cells had eccentric nuclei and concentric eosinophilic cytoplasmic globules closely resembling the cells in the aspirates (Figure 2B). Moderate cellular pleomorphism and 4 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields were observed. There were several foci of necrosis filled with neutrophils, and foci of chronic hemorrhage containing extracellular hemosiderin pigment. The neoplasm was classified as hemangiosarcoma based on the formation of vascular channels containing RBCs.

Histologic section of an epithelioid hemangiosarcoma from a dog. (A) Densely packed neoplastic cells form collapsed vascular channels. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×40. (B) Primitive capillaries contain eosinophilic material (arrow) or RBCs (arrowheads). Hematoxylin and eosin, ×80. Immunohistochemical stains show expression of (C) vimentin (streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase-vector red substrate) and (D) von Willebrand's factor (Vectastain-ABC-peroxidase-3,3′diaminobenzidine) by neoplastic cells. ×20.

Immunohistochemistry

Because of conflicting cytologic and histologic assessments of the caudal abdominal mass, immunohisto-chemical tests were performed on paraffin-embedded sections of the biopsy sample using a panel of antibodies specific for epithelial or mesenchymal cell markers. The panel included markers for cytokeratin (prediluted polyclonal antibody), vimentin (prediluted monoclonal anti-swine), von Willebrand's factor (vWF; prediluted dilution of monoclonal antibody to human vWf), and CD31 (JC70 diluted 1:50) (Dako, Carpinteria, Calif, USA). Streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase-vector red substrate and Vectastain-ABC-peroxidase-3,3’diaminobenzidine stains were obtained from Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif, USA.

The neoplastic cells were negative for cytokeratin (data not shown) but positive for vimentin (Figure 2C) and von Willebrand's factor (Figure 2D). The cells also stained weakly positive with anti-CD31 antibody (data not shown).

Clinical Outcome

Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide combination therapy was initiated, and the dog was released from the hospital on piroxicam (0.3 mg/kg once daily) as potential immunomodulatory therapy, and combination antibiotic-steroid drops and atropine for the hyphema. Based on the diagnosis of hemangiosarcoma, the long-term prognosis for the dog was poor, and the dog was euthanatized with progressive disease 4 months after diagnosis.

Discussion

The cytologic features of this hemangiosarcoma were unusual, and suggested that the neoplastic cells were of epithelial origin. However, many of the same cytoarchi-tectural features that suggested epithelial cell origin also indicated endothelial cell differentiation. These features included intracytoplasmic microlumina that often contained RBCs or neutrophils and microacinar lumen formation.1 Although hemangiosarcomas in domestic animals can be very pleomorphic, epithelioid variants of hemangiosarcomas or angiosarcomas occur in human beings. These variants can be difficult to differentiate from epithelial neoplasms because of their overlapping cytologic and histologic features.2 The cytologic features noted in the current report have been described for epithelioid sarcomas and angiosarcomas that develop in people de novo or after radiation.3,4 In a recent report on the cytology of 15 cases of anigosarcoma, vasoformative features defined as intracytoplasmic lumina with or without RBCs, microacinar lumen formation, and signet-ring-like cells were identified in 10 cases.1 These features should not be considered diagnostic of endothelial cell differentiation, but they support this diagnosis when combined with histologic evidence of tumor cells lining unequivocal vascular spaces.

Using immunohistochemistry and an antibody panel for intermediate filaments and endothelial cell antigens, we confirmed endothelial differentiation of the neoplastic cells. The tumor from this dog was positive for vimentin (an intermediate filament of mesenchymal cells) but not for pancytokeratin. The former result was expected, because vascular endothelial cells are mesenchyme-derived epithelioid lining cells. However, expression of keratin has been documented in human epithelioid angiosarcomas and in subsets of normal endothelium.5 Specific markers such as vWf and CD31 are used to define endothelial cell differentiation. CD31 is a 100–kd glycoprotein, also called platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule, which allows platelets to adhere to endothelium.6 Although CD31 expression has been reported in poorly differentiated canine hemangiosarcomas that are negative for vWF,7 immunoreactivity for both endothelial cell markers was evident in this tumor.

Cytologic assessment of hemangiosarcoma can be challenging because of the pleomorphic nature of the neoplastic endothelial cells. Although identification of vascular structures in the biopsy sample provided the diagnosis in this case, the cytologic features of the aspirates remarkably resembled the vasoformative features described in aspirates of human angiosarcomas.1,3 However, differentiation of the intracytoplasmic vasoformative lumina from cytophagia by neoplastic cells would be difficult based on cytology alone. In many cases, demonstration of endothelial cell markers and ultrastructural features, including pericytes, pinocytotic vesicles, and closed fenestrations, together with cytologic vasoformative features are necessary to make a final diagnosis.8–10 Hemangiosarcoma should be included as a differential tumor type when intracytoplasmic lumina or vasoformative features are identified in cytologic specimens of loosely cohesive round neoplastic cells.