ANATOMIC VARIATIONS OF FELINE INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL JUGULAR VEINS

Abstract

We evaluated 50 feline head and neck computed tomography examinations to determine the prevalence of vascular variation in the internal and external jugular veins. We identified three distinct anatomic conformations of the internal jugular vein. No variation of external jugular vein morphology was detected. Feline patients can have different internal jugular vein morphology that should be recognized for surgical planning.

Introduction

Contrast computed tomography (CT) of the head and neck is performed commonly in cats with nasopharyngeal mass, polyp, otitis, intracranial lesions, and cervical mass.1-6 In CT images with intravenously injected iodinated contrast medium, radiologists usually assess regional arteries and veins for alterations such as thrombosis, neoplastic vascular invasion and angiogenesis, especially for surgical planning.7 More specifically, laryngeal, pharyngeal, parotid or mandibular salivary gland procedures, thyroidectomy, or other mass removal in the cranial cervical region requires a thorough understanding of vascular topography.

Embriologically, the veins of the neck arise from the superficial capillary plexus. Initially, they form the superficial veins that subsequently join the distal part of the precardinal vein forming the internal jugular veins.8 Both internal and external jugular veins are present in the cat and dog while only the external jugular vein is described in the horse.9-12 The internal jugular vein drains cerebral structures, exiting the skull at the jugular foramen and is located between the common carotid artery and the trachea in the cervical region, joining the external jugular vein at the base of the neck.9 Anatomic vascular variations in the cat consisting of the absence of one external jugular vein and one or both internal jugular veins have been reported.13, 14 Anastomosis of the internal jugular vein with external jugular vein shortly after exiting from the jugular foramen and absent or vestigial internal jugular vein are the most common variations.13 Anatomic variations of the internal jugular veins exist in people as well.15 Furthermore, the relative size of the external and internal jugular veins is unknown.

Our aim was to evaluate the incidence of anatomic vascular variations in the feline head and neck based on postcontrast CT images.

Materials and Methods

CT images of cats that underwent CT examination of head and neck between 2008 and 2011 at our institutions were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were presence of postcontrast CT images of the head and neck, absence of diseases potentially influencing jugular vein topography, and absence of vascular thrombosis.

CT studies had been performed with a single slice1 scanner or a 42 or 163 multidetector-row scanner. Images were acquired with the helical scan mode, 120 kVp, 1.25 mm slice thickness, slice interval 0.625–1.25, and pitch 0.938–1.5. Images through the neck and head region were acquired before and after intravenous iodinated contrast-medium4 administration (600 mg I/kg). CT examinations were reviewed by a board-certified veterinary radiologist (LB) and the morphology of the jugular veins was assessed on postcontrast transverse images. Presence or absence of internal and external jugular veins, their relative location and presence of anastomosis with others vessels were described. The diameter of all jugular veins was measured on transverse images at the level of C1 using a digital caliper5 and expressed in terms of mean and standard deviation.

Results

Images from 50 cats were evaluated. There were no abnormalities of the external jugular vein. When present, the internal jugular vein was located lateral and in close relationship with the carotid artery and dorsomedial to the external jugular vein.

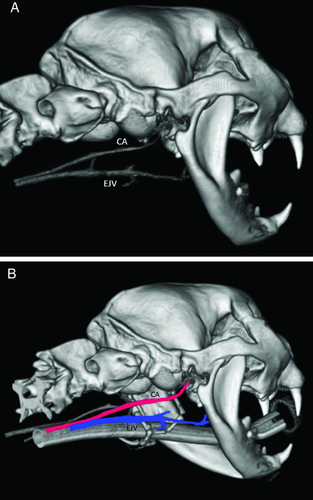

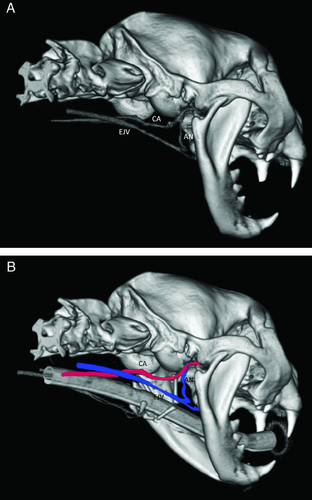

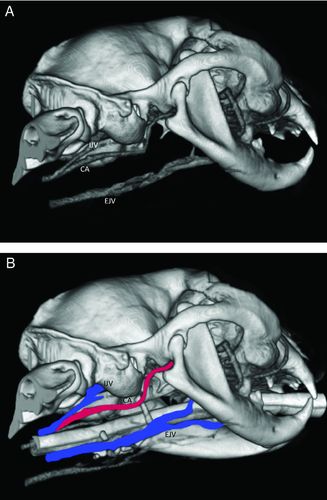

We defined three types of vascular variations for the internal jugular vein: type I: internal jugular vein ended a few millimeters caudal to the jugular foramen, joining the vertebral vein (Fig. 1); type II: internal jugular vein ended a few millimeters caudal to the jugular foramen, joining the vertebral vein and the external jugular vein by a tortuous anastomosis (Fig. 2); and type III: internal jugular vein exited the jugular foramen and divided into two branches with one joining the vertebral vein and the other running caudally, joining the external jugular vein at the thoracic inlet (Fig. 3);

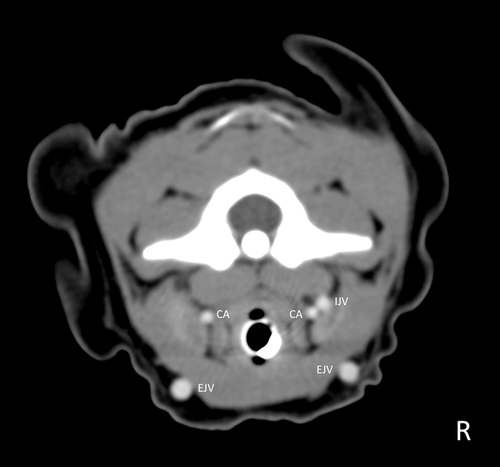

The type I variation was detected in 31 cats in the right internal jugular vein and in 33 in the left internal jugular vein. The type II pattern was observed in eight cats in the right internal jugular vein and in six in the left internal jugular vein. The type III conformation, corresponding to the normal topographic behavior described previously,9-11 was noted in 11 cats in the right internal jugular vein and in 11 in the left internal jugular vein. The left to right combinations of vascular morphology are reported in Table 1. In types I and II, no internal jugular vein was present at the level of C1 and no measurement was made (Fig. 4). In type III conformation, the mean and standard deviation (SD) of vessel diameters were 2.44 mm (SD ±0.65) and 2.77 mm (SD ±0.71) for the left and right internal jugular vein, respectively, and 3.76 mm (SD ±0.70) and 3.74 mm (SD ±0.73) for the left and right external jugular vein, respectively.

| Left | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | I | II | III | |

| Right | I | 46%, n = 23 | 6%, n = 3 | 8%, n = 4 |

| II | 8%, n = 4 | 6%, n = 3 | 2%, n = 1 | |

| III | 14%, n = 7 | 0%, n = 0 | 10%, n = 5 | |

Discussion

In humans, there is often collapse of the internal jugular vein due to the upright position.16 Sternal recumbency, as used in our cats, likely generates less of a gravitational effect on jugular veins lying in a dorsal plane compared to the vertical position in people. Central venous pressure was not evaluated in these cats, but the finding of asymmetric left to right vascular architecture in many cats is not consistent with low central venous pressure, since low blood pressure would likely influence both sides similarly. Furthermore, the presence of consistently observed anastomotic vessels also favors true anatomic variation and not collapse due to low blood pressure.

Absence of the left external jugular vein and both internal jugular veins has been reported.14 Based on our results, the absence of one or both internal jugular veins was common and should not be interpreted as an abnormality. No alteration was noted concerning the external jugular vein, meaning that any discrepancy from normal should be considered an anomaly for this vessel.

The internal jugular vein has been described as being located between the carotid artery and the trachea.9-12 We observed that in cats with a type III conformation, the internal jugular vein was lateral to the carotid artery and dorsomedial to the external jugular vein.

As we did not evaluate the hydration status of each cat, and cats received variable amounts of intravenous fluids during anesthesia, this could have influenced the volume of circulating blood and potentially changed the internal jugular vein appearance. Furthermore, the contrast medium protocol was not standardized, which potentially influenced the visualization of some vessels.

In conclusion, there are variations in the morphology of the internal jugular vein in cats. This information will help avoid misinterpretation of postcontrast CT evaluation of head and neck in cats with diseases of the head and neck.