IMAGING DIAGNOSIS—DIOCTOPHYMA RENALE IN A DOG

Signalment

Nine-year-old, 12 kg, intact male, crossbred dog.

History and Physical Findings

The dog was used for teaching in parasitology classes and had become naturally infected with Dioctophyma renale. The dog was referred to the Teaching Hospital because ova of this parasite were found in the urinary sediment. Results of urinalysis were reddish urine, a specific gravity of 1.010, and the presence of red and white blood cells. Hematologic and serum biochemical values were normal.

Imaging

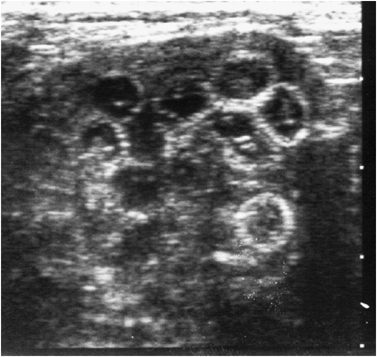

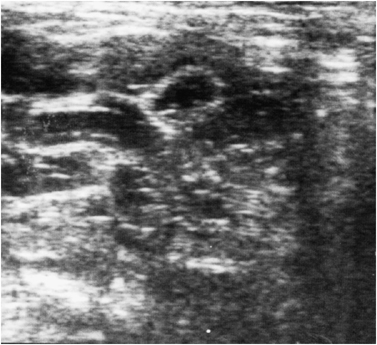

In abdominal radiographs, there was an enlarged right kidney and the ratio of its length to the length of a vertebra was 5 (normal range, 2.5–3.5). Sonographically, the right kidney was larger than the left and there were multiple ring-like structures in the pelvis of the right kidney measuring between 5 and 10 mm in diameter. These structures had a double-layer wall; the outer was hyperechoic and the inner hypoechoic, containing internal echos (Fig. 1). These structures deformed the silhouette of the kidney. In the longitudinal plane, these ring-like structures were visualized as bands, with alternating hypo- and hyperechoic layers (Fig. 2). The kidney was outlined by a thin hyperechoic rim. The left kidney appeared normal. The ultrasonographic findings, and the presence of ova of Dioctophyma renale in the urine sediment, were consistent with the presence of a gravid female parasite in the right kidney.

Transverse ultrasound image of the right kidney containing multiple ring-like structures with a double-layered wall, consistent with the adult form of Dioctophyma renale.

Longitudinal ultrasound image of the right kidney where the parasite is visualized as bands with alternating hypo- and hyperechoic layers.

Diagnosis

A right nephrectomy was performed. The enlarged right kidney was essentially a sac containing two parasites, one female and one male.

Discussion

Dioctophyma renale is a parasitic nematode of fish-eating mammals, especially minks, otters, martens, other wild carnivores and also domestic animals like dogs, pigs, and horses.1 It rarely affects humans.2 The life cycle of the worm requires two intermediate hosts, annelids and freshwater fish. Infection in mammals is attributable to eating raw fish or frogs, or drinking water that contains infected annelids.3

In the final host, the infective larvae penetrate the bowel wall, and primarily infect the peritoneal cavity and kidneys, especially the right kidney due to its proximity to the duodenum.1,4,5 Infections are often asymptomatic unless there is bilateral renal infection or unilateral infection with concurrent disease in the contralateral kidney.4,5 Diagnosis depends on the demonstration of ova of Dioctophyma renale in urine sediment, although these will be found only if gravid females are present in the kidney, which occurs in 40% or less of infected dogs.4 The enlarged kidney may be apparent radiographically. If excretory urography is performed, the parasitized kidney may be unable to excrete contrast medium.1 Sonographically, the infected kidney may contain excessive fluid due to the destruction of the renal parenchyma. The mechanism of destruction is not known, but obstruction and secondary hydronephrosis are important factors.1 In our patient, we were also able to see multiple ring-like structures with a double-layer wall, representing the parasite.