ULTRASONOGRAPHIC EVALUATION OF THE OMASUM IN COWS AND BUFFALOES

Abstract

The study was conducted to establish the ultrasonographic features of the healthy and impacted omasum in cows and buffaloes. Scanning was done using a 3.5 MHz microconvex transducer. In healthy buffaloes, the omasum could be scanned at the eighth to ninth intercostal space as a round or oval structure having thick echogenic wall with echogenic leaves. Gradual slow movements of omasal leaves could also be seen in real-time B-mode. The omasum appeared to be very clear, large, and close to the transducer at the start of the omasal contraction, and as the contraction progressed the omasum retracted away from the transducer and became very small. In healthy cows the omasum was seen as a crescent-shaped structure with an echogenic wall. The contents of the omasum or omasal leaves could not be visualized. Omasal contractility was not as prominent as in buffaloes. In buffaloes, the impacted omasum appeared amotile, the omasal leaves were not visible, and the omasum as a whole gave a prominent distal acoustic shadow. In cows, the impaction could be diagnosed based on amotile omasum covering a large area on the right side. Ultrasonography was found to be helpful in subjective assessment of omasal impaction but could not aid in diagnosing the severity of impaction.

Introduction

The omasum is the third compartment of the bovine stomach. It is an ellipsoidal organ located toward the right of the median plane opposing the seventh to eleventh rib.1 Omasal leaves provide a large surface area for absorption of volatile fatty acids, electrolytes, and water.2 The omasum also acts to reduce the size of feed particles3 but this mechanical function may be of minor importance.4

In tropical countries omasal impaction is prevalent in cows5 and buffaloes.6 Chronic omasal impaction as a clinical entity is difficult to define and is usually diagnosed at necropsy when the omasum is enlarged and firm.7 The omasum may also be affected by other disorders such as traumatic reticuloperitonitis, right-sided abomasal displacement with or without abomasal torsion, and pyloric stenosis.8,9 Because of its anatomic position the omasum is not easily accessible for clinical examination by palpation, percussion, or auscultation.10,11 Confirmative diagnosis of omasal disorders can primarily be made from an exploratory laparorumenotomy6 or postmortem examination and rarely by per-rectal examination.7 The omasum cannot be evaluated by radiography12 or laparoscopy.13

In recent years ultrasonography has been successfully used to examine the gastrointestinal tract14,15 and the healthy omasum8 in cows. In buffaloes, ultrasonography has been used successfully to diagnose reticular diaphragmatic hernia.16 Ultrasonographic features of the omasum in buffaloes have not been described. No reports are available on the ultrasonographic features of omasal impaction in cows and buffaloes. We describe the ultrasonographic features of the normal omasum in vitro, in vivo, and of the impacted omasum in cows and buffaloes.

Materials and Methods

The present study was done in three phases. In the first phase, the apparently normal omasum was collected from two buffaloes dying of causes unrelated to omasal disease. The omasum was filled with water and tied at both open ends. The ultrasonographic features of the normal omasum and omasal leaves were recorded by placing the omasum in a water bath and the transducer directly over the serosal surface of the water-filled omasum. Scanning was done using a Concept/MCV Veterinary Ultrasound Scanner,* in real-time B-mode with a 3.5 MHz microconvex transducer to characterize the normal structure of the omasum.

In the second phase, the omasum was scanned in two apparently healthy adult female buffaloes and two cows. Ultrasonography was done in the restrained standing animal without any sedation. For ultrasonographic examination of the omasum, the ventrolateral aspect of the abdomen on right side from the level of the elbow to the ventral midline extending from the sixth to 11th intercostal space was shaved and acoustic coupling gel was applied liberally for optimal transmission of the ultrasound waves. The omasum was scanned at the eighth and ninth intercostal space by placing the transducer at each intercostal space beginning dorsally at the right lateral aspect (just dorsal and lateral or near to the milk vein) and progressing ventrally with the transducer parallel to the ribs.

In the third phase, 25 buffaloes and five cows suspected of forestomach disorders were scanned to record the ultrasonographic features of the omasum. Exploratory laparorumenotomy was done in all the animals to confirm the ultrasonographic findings. In two buffaloes during exploratory laparorumenotomy the transducer was fixed in a position to identify the omasum. The omasum was then filled with water through the reticulo-omasal orifice and the filling of omasum was seen in real-time B-mode. This was done to confirm that the organ that was being scanned was actually the omasum. In all the animals the approximate size of the omasum was assessed using hand breadth during laparorumenotomy and the omasum was flushed with tap water under moderate pressure along with kneading to relieve the impaction. The severity of omasal impaction was graded as mild, moderate, and severe based on the difficulty in evacuation of the omasal contents.

Results

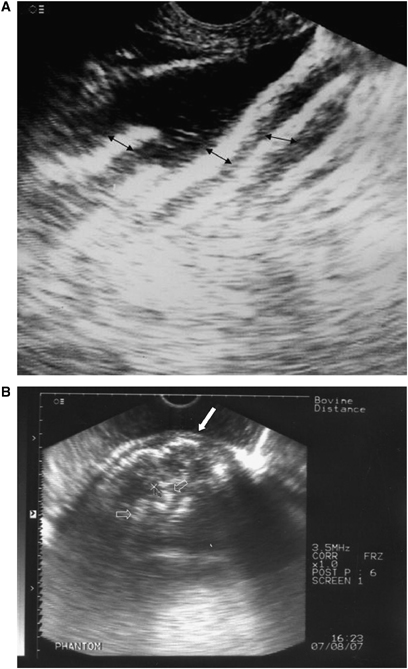

In Phase I the echogenic omasal wall and hyperechoic omasal leaves were separated by anechoic water (Fig. 1A). The wall of omasum appeared as a thick echogenic crescent-shaped line (Fig. 1B).

(A) Ultrasound image of ex vivo omasum. Note the hyperechoic omasal leaves (arrows) separated by anechoic water between the leaves. 125 × 120 mm (96 × 96 DPI). (B) Ultrasound image of ex vivo omasum. Note the thick echogenic wall (arrow) and hyperechoic omasal leaves (hollow arrows). 174 × 125 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

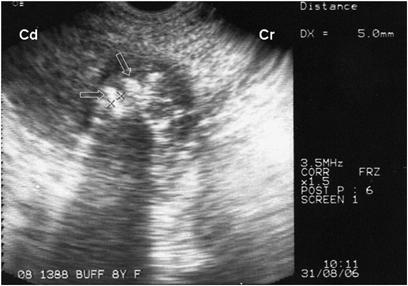

In healthy buffaloes (Phase II), the omasum was seen at the eighth to ninth intercostal space as a round or oval structure having a 7–9.5-mm-thick echogenic wall with echogenic leaves ranging from 5 to 7 mm in thickness without distal acoustic shadowing (Fig. 2). The medial wall of the omasum was not clearly defined in majority of the animals. Gradual slow movements of omasal leaves could also be seen in real-time B-mode in all animals. The omasum appeared to be very clear, large, and close to the transducer (Fig. 3) at the start of the omasal contraction, and as the contraction progressed the omasum retracted away from the transducer and became very small (Fig. 4). This cycle repeated after every 1–1.5 min with each omasal contraction.

Omasum in a healthy buffalo appearing as a round or oval structure with echogenic leaves (hollow arrows). 180 × 125 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

Ultrasonographic image showing a clear and large omasum (marked by arrows) close to the transducer at the start of the omasal contraction in a healthy buffaloe. Hyperechoic omasal leaves (hollow arrows) are also visible. 180 × 127 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

Ultrasonographic image of a small omasum retracted away from the transducer at the extreme of motility in a healthy buffalo. 190 × 141 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

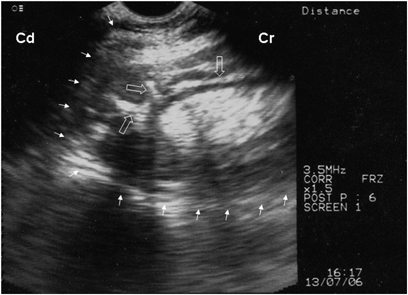

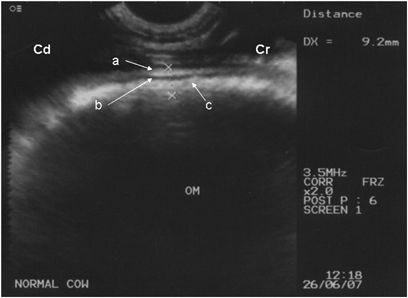

In healthy cows (Phase II) the omasum could also be visualized at the eighth to ninth intercostal space (Fig. 5). However, the omasum was seen as a crescent-shaped structure with an echogenic wall 9–10.2 mm in thickness (Fig. 6). The tunica serosa was evident as a thin echogenic line while the muscularis layer was hypoechoic separating the thick echogenic mucosa (Fig. 6). The contents of the omasum could not be visualized. The leaves of the omasum could be visualized occasionally. The medial wall of the omasum could not be seen in any of the cows. Omasal contraction could be recorded but was not as marked as in buffaloes. The omasum never retracted away from the transducer, however, the size of the omasum reduced to a certain extent with each contraction.

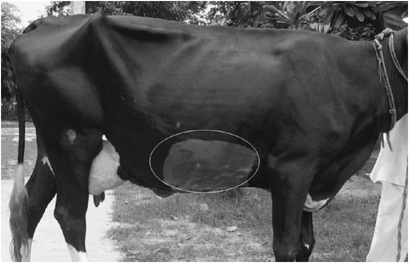

Area of omasal scanning in a healthy cow. 220 × 141 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

Omasum seen as a crescent-shaped structure with a thick echogenic wall in a healthy cow. The tunica serosa (a) was evident as a thin echogenic line while the muscularis layer (b) was hypoechoic separating the thick echogenic mucosa (c). 193 × 141 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

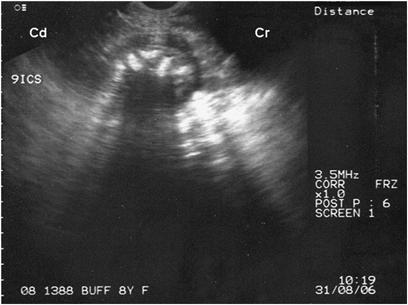

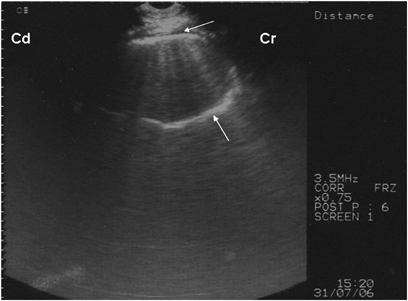

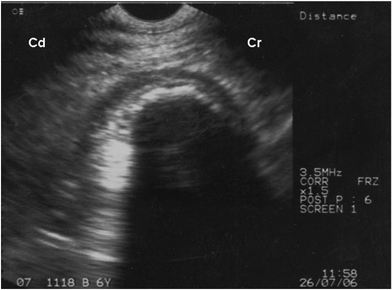

In the third phase 25 buffaloes and five cows clinically suspected for forestomach disorders were subjected to ultrasonography. To confirm what was being seen was actually omasum, the filling of the omasum with water was seen using real-time B-mode. The distended omasum appeared as an anechoic structure with displacement of omasal leaves toward periphery or corners (Fig. 7). Out of 25 buffaloes, 13 were suspected of having omasal impaction based on ultrasonography. In these buffaloes omasal leaves appeared amotile or were not visible and the omasum as a whole created a prominent distal acoustic shadow (Fig. 8). The omasum never retracted away from the transducer which confirmed absence or minimal contractility of omasum in all animals. In eight buffaloes the omasum could be scanned as cranial as the seventh intercostal space, while in four buffaloes, the caudal limit of omasum extended up to the 11th intercostal space. Similarly, in six buffaloes the omasum could be scanned up to the ventral midline, while in an equal number of buffaloes, the dorsal limit of omasum extended beyond the level of right elbow. The medial wall could not be visualized in any animal. These findings were suggestive of omasal distension and impaction. Exploratory laparorumenotomy allowed identification of a distended omasum in all buffaloes (n=13), with a hard solid consistency that confirmed the ultrasonographic findings. The diameter of omasum was >12 in. in these animals. The contents of impacted omasum were hard pellets or flakes of undigested wheat straw. Mild omasal impaction was recorded in two buffaloes while moderate and severe impaction was seen in eight and three buffaloes, respectively.

The water-filled distended omasum appears as an anechoic structure (arrows) with displacement of omasal leaves toward the periphery in buffalo. 180 × 127 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

Impacted omasum with a marked distal acoustic shadow in a buffalo. 188 × 139 mm (96 × 96 DPI).

Out of five cows, four were diagnosed with omasal impaction based on ultrasonography. In these cows the omasum appeared amotile extending cranially up to the seventh intercostal space in all the cows and caudally up to the 11th intercostal space in three cows. The omasum extended up to ventral midline in two animals and dorsally the omasum was evident up to the middle third of rib cage in all the four animals. On laparorumenotomy, all the four cows had severe omasal impaction and the diameter of omasum was greater than 12 in. As seen in buffaloes, the contents of impacted omasum were hard pellets or flakes of undigested wheat straw.

Twelve buffaloes and one cow had a normal omasum during ultrasonography, which was confirmed upon exploratory laparorumenotomy. In some buffaloes partial acoustic shadowing was apparent distal to omasum, but due to the presence of omasal contractions the omasum was declared normal. In two buffaloes, on laparorumenotomy, the omasum was distended but impaction was ruled out on palpation.

Discussion

Ultrasonography of the omasum was performed in all animals using a 3.5 MHz microconvex transducer in real-time B-mode which was easy to maneuver in the narrow intercostal spaces. The omasal wall could be scanned closest to the abdomen at the eighth and ninth intercostal space in healthy cows at a depth of 0–5.3 cm and the wall was farther away toward the dorsal and ventral limits.8 Use of a 3.5 MHz transducer in the present study provided adequate depth for scanning of omasum. The animals were restrained in a cattle crate and scanning was done in the standing position and did not require sedation. The scanning of the omasum was possible at the eighth and ninth intercostal space in all the cows and buffaloes, which was similar to earlier findings.8 The omasal wall was thicker in cows as compared with the buffaloes. The omasal leaves could be visualized in buffaloes but could not be seen in cows during ultrasonography. Similarly, omasal contractility was more prominent in buffaloes than in cows. These differences could be attributed to species variation. However, it has been reported that in healthy cows the omasum did not appear to have any active motility of its own.8 The omasal contractility recorded in buffaloes was typical and could be easily identified during ultrasonography. The type of contractions in the present study conformed to the churning movements of the omasum which help in breakdown of feed particles.3 The ultrasonographic diagnosis of omasal impaction in buffaloes and cows was based on the extent of area covered by the omasum and the absence of omasal contractility. In buffaloes, prominent distal acoustic shadowing was also a diagnostic feature of omasal impaction which otherwise was rarely observed in healthy animals. The extent of the omasum in impaction varied from the seventh intercostal space cranially to the 11th intercostal space caudally. However, it was suggested that omasum can extend from the sixth to 11th intercostal space but is visualized at the eighth and ninth intercostal space in healthy cows.8 The ultrasonographic findings of an impacted omasum could be correlated with the laparorumenotomy findings but the severity of omasal impaction could not be assessed ultrasonographically. The medial wall of the omasum could not be visualized in any of the animals which may be due to attenuation of ultrasound waves by the impacted nature of the contents thereby producing acoustic shadowing. Finely chopped wheat straw has been incriminated as a major cause of omasal impaction in buffaloes.6 In the present study no false-positive results were recorded and ultrasonographic findings of the healthy and impacted omasum conformed to the laparorumenotomy findings. However, in two buffaloes the distended omasum could not be assessed ultrasonographically.

In conclusion, ultrasonography is a noninvasive method to evaluate the status of the omasum in cows and buffaloes. Ultrasonography was found to be helpful in subjective assessment of omasal impaction but could not aid in diagnosing the severity of impaction.