Epidemiology of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis

Invited review

Abstract

Larson DA, Derkay CS. Epidemiology of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. APMIS 2010; 118: 450–454.

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) was first described in the 1800s, but it was not until the 1980s when it was convincingly attributed to human papilloma virus (HPV). RRP is categorized into juvenile onset and adult onset depending on presentation before or after the age of 12 years, respectively. The prevalence of this disease is likely variable depending on the age of presentation, country and socioeconomic status of the population being studied, but is generally accepted to be between 1 and 4 per 100 000. Despite the low prevalence, the economic burden of RRP is high given the multiple procedures required by patients. Multiple studies have shown that the most likely route of transmission of HPV in RRP is from mother to child during labor. Exceptions to this may include patients with congenital RRP who have been exposed in utero and adult patients who may have been exposed during sexual contact. Although cesarean section may prevent the exposure of children to the HPV virus during childbirth, its effectiveness in preventing RRP is debatable and the procedure itself carries an increased risk of complications. The quadrivalent HPV vaccine holds the most promise for the prevention of RRP by eliminating the maternal reservoir for HPV.

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infections can occur at any portion of the upper aerodigestive tract, although it is most extensively described in the larynx and trachea in the form of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP). RRP was first described in the late 1800s by Sir Morrell Mackenzie who recognized papillomas as a distinct lesion of the larynx in children (1). It was not until the advent of modern molecular genetic techniques in the 1990s that HPV was confirmed as the causative agent of RRP. Of more than 100 serotypes of HPV, types 6 and 11 are most common in RRP (2).

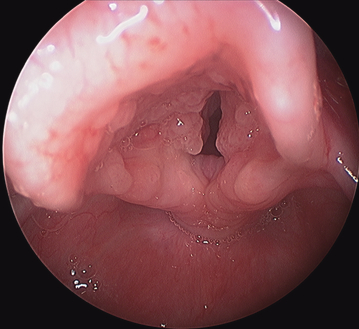

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis is characterized by exophytic, wart-like lesions of the upper airway that tend to recur and have the potential to spread throughout the respiratory tract (Fig. 1). RRP is a benign disease, although it can have significant morbidity and rare mortality secondary to airway obstruction. There is also a small, less than 1%, risk of malignant transformation (3). The course of RRP is variable with some patients experiencing spontaneous regression and others suffering from aggressive papilloma growth requiring multiple surgical procedures for management. Multiple studies have shown that infection with HPV 11 is associated with a more aggressive disease course requiring more surgical procedures for control. It is estimated that in the United States there are as many as 15 000 surgical procedures performed every year in adults and children with a total health care cost of nearly $150 million (4).

Laryngeal papillomas.

Incidence and prevalence

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis is categorized into juvenile onset (JORRP) and adult onset (AORRP) based on diagnosis before or after 12 years of age, respectively. The disease has been observed in patients during the immediate postnatal period and in patients as old as 84 years (4). Juvenile-onset RRP is most commonly diagnosed between 2 and 4 years of age with dysphonia being the most common presenting complaint (5, 6). The majority of JORRP patients (75%) have been diagnosed by 5 years of age. Children who are diagnosed at a younger age have a higher risk for disease progression compared with children diagnosed later in life (7). Studies have shown no sex predilection among children with RRP. In AORRP, the peak incidence is between 20 and 40 years of age and there is a slight male predilection (6). Anecdotal observations suggest that most pediatric patients are first born, have young primagravid mothers, and come from families of low socioeconomic status (4, 8, 9).

Numerous studies have been performed to elucidate the true incidence of RRP. Recently, Campisi created a national database incorporating all children (less than 14 years old) with RRP in Canada treated by Pediatric Otolaryngologists. This study found the national incidence of JORRP from 1994 to 2007 to be 0.24 per 100 000 with a prevalence of 1.11 per 100 000 (10). These estimates are significantly lower than in several previous studies, but similar to a population-based study of RRP patients in Seattle and Atlanta (11). The authors attribute this discrepancy to either overestimations by other studies based on extrapolated data or higher incidences in other countries. In a Danish study incorporating 50% of the population of that country, the overall incidence of RRP was 3.84 cases per 100 000. The rate among children in that study was 3.62 per 100 000, while adult-onset cases occurred at a rate of 3.94 per 100 000 (12). These numbers are comparable with those found in a U.S. study in which a survey of Board-certified otolaryngologists estimated the incidence of RRP in the pediatric population to be 4.3 per 100 000 and in the adult population to be 1.8 per 100 000 (4).

Interestingly, a recent pilot study of a large database of publically and privately insured patients in the United States consistently showed that RRP incidence was higher in publically insured patients compared with those with private insurance (3.21 vs 1.98 per 100 000, respectively) (13). An explanation for this may be that patients with public insurance tend to come from a lower socioeconomic level than those with private insurance. A cross-sectional study of all active JORRP patients from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto showed that nearly half of these patients were below the poverty line in Canada (14). This study, however, showed no correlation between socioeconomic status and severity of disease.

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis places a large economic burden on individual patients and their families as well as society as a whole. On average, a child presenting to an academic center in the United States with RRP requires 19.7 procedures over their lifetime, with a mean frequency of procedures being 4.4 per year (15). Approximately equal numbers of adults and children with RRP (17% vs 19%, respectively) will have aggressive disease requiring more than 40 lifetime procedures. The average lifetime cost to treat one patient with RRP has been estimated at $60 000–$470 000 in the United States (13).

Transmission

The near universality of HPV in humans has been well documented. By far the largest reservoir of this virus, especially for types 6, 11, 16, and 18, is the ano-genital tract. It is from this source that HPV infections of the respiratory tract are believed to originate.

Human papilloma virus infection of the ano-genital tract is the most common sexually transmitted infection in humans. The prevalence of clinically apparent genital papilloma in the United States is in approximately 1% of the population (16). These most often manifest as condylomata acuminata involving the cervix, vulva or other ano-genital sites in women, and the penis and anus in men. However, the 1% of the population that has clinically apparent disease is only a small minority of all patients who have been exposed to HPV. It is estimated that 10–20% of the population of the United States between 15 and 49 years of age are DNA positive for HPV. In addition, 60% of women of childbearing age are antibody positive and DNA negative for HPV, indicating a past exposure. Clinically apparent HPV infection has been noted in 1.5–5% of pregnant women in the United States (17).

The exact mode of HPV transmission in RRP remains elusive and is likely variable depending on the age of the patient at presentation. Several studies have convincingly linked JORRP to mothers with active genital HPV infections; among adults, circumstantial evidence suggests that the disease may be associated with oral–genital contact (18).

Retrospective and recent prospective studies have confirmed that HPV may be passed by vertical transmission from mother to child (19–21). Silverberg et al. showed that children born to mothers with active condylomata had a 231-fold increased risk of developing RRP when compared with children born to disease-free mothers (22). In addition, they showed that children born to women with active condylomata had a twofold higher risk of developing RRP if labor lasted more than 10 h. Kashima et al. found that childhood-onset RRP patients were more likely to be first born and vaginally delivered than were control patients of similar age (18). The authors hypothesized that primagravid mothers are more likely to have a long second stage of labor and that the prolonged exposure to HPV in the birth canal leads to a higher risk of infection in the first-born child. They also suggested that newly acquired genital HPV lesions are more likely to shed virus than long-standing lesions. This would explain the higher incidence of RRP observed among the offspring of young mothers of low socioeconomic status – the same group that is more likely to acquire sexually transmitted infections such as HPV. Hallden and Majmudar showed that 54% of JORPP patients were born to mothers with a history of vulvar condylomata at the time of delivery (23). Despite this apparent close association, few children exposed to genital warts at birth actually develop clinical disease (24). It is not well understood why RRP develops in so few children whose mothers have condylomata. Although HPV could be recovered from the nasopharyngeal secretions of 30% of infants exposed to HPV in the birth canal, the number of infants expected to manifest evidence of RRP is only a small fraction of this (25). Based on these data, it appears that secondary factors such as: patient immunity; timing, length, and volume of virus exposure; and local traumas (intubation, extra-esophageal reflux) must be important in the development of RRP. Reports of neonatal papillomatosis suggest that, in at least some cases, development of the disease may occur in utero. As caesarean section does not seem to prevent the development of RRP in all cases, a better understanding of the risk factors associated with RRP is needed before the efficacy of caesarean delivery in preventing papilloma disease can be fully assessed (8).

Among patients with AORRP, a case–control study found them more likely to have more lifetime sexual partners and a higher frequency of oral sex than those reported in adult controls (18). These data would suggest that patients with AORRP are exposed later in life than patients with JORRP. However, HPV has the disturbing capability to form latent infections in the basal cell layer of otherwise healthy appearing mucosa (26–28). It has been suggested that AORRP may represent a reactivation of HPV infection acquired during birth instead of a de novo exposure during adulthood.

Prevention

The goal of current surgical treatment modalities (e.g. CO2, KTP and Flash dye lasers; microdebrider; and ‘cold’ steel) for the management of RRP is control of the disease, preservation of the voice and prevention of major complications until the disease spontaneously resolves. Given the large number of procedures needed and the high cost of treatment per patient, the ideal goal would be prevention of the disease in the first place.

Intuitively, caesarean section would seem to reduce the risk of vertical transmission of HPV. However, this procedure is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality for the mother and a much higher economic cost than elective vaginal delivery. Shah et al. estimated that the risk of a child contracting the disease from a mother who has active condylomata and delivers vaginally is only about 1 in 400 (8). The characteristics that differentiate this one child from the other 399, as previously discussed, remain unknown. Given the uncertainty surrounding intra-partum exposure, there is presently insufficient evidence to support delivery by caesarean section in all pregnant women with condylomata (29). However, there may be some benefit in managing condyloma during pregnancy if it can be accomplished without increasing the miscarriage rate. Discussion between the at-risk mother and her obstetrician regarding the issue of HPV transmission would seem appropriate.

The most interesting and promising recent development in the prevention of RRP is the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (GARDASILTM; Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). This vaccine is currently licensed by the FDA for the prevention of cervical cancer, adenocarcinoma in situ, and intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1–3; vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasias grades 2–3; and genital warts associated with HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 (30). The United States Center for Disease Control Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has recommended vaccination for all girls aged 11–12 years, girls and women aged 13–26 years who have not yet been vaccinated, and girls as young as aged 9 years, where the physician feels it would be appropriate (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/downloads/resolutions/1009hpv-508.pdf). Recently, boys aged 9–18 years have been included in the groups of patients eligible for vaccination with the quadrivalent vaccine. Based on these recommendations, numerous countries have passed laws to educate the public and encourage use of the vaccine, but few states in the United States have mandated vaccination (31). Based upon the available clinical studies, the vaccine is predicted to reduce the incidence, morbidity, and mortality of cervicovaginal HPV disease. An added, and often overlooked, benefit may be a concomitant decrease in the incidence of RRP in all age groups. In addition, there may be a reduction in 20–25% of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas attributed to HPV (32). Theoretically, universal vaccination with the quadrivalent vaccine could lead to the elimination of the maternal and paternal reservoir of HPV and lead to a near eradication of RRP caused by HPV 6 and 11. Given the rarity of RRP, multi-institutional studies will have to be continued for many years to observe any decrease in the incidence of RRP secondary to widespread vaccination.