Can Nature Drive Economic Growth?

A teaching note is available from Dr. Mathews upon request.

Abstract

The conditions that lead to successful economic development are diverse and place sensitive. Recent research supports the notion that there is a correlation between the presence of natural amenities and rural economic development. This case explores the situation of a rural county that is faced with constrained development options as a result of a significant federal footprint on the county's land area. The actions of the federal agencies managing the resources impact the economic vitality of the region. Two issues currently under review challenge the county to think critically about its potential for using nature as an economic development tool.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports that U.S. rural populations have 24% lower incomes than their metropolitan counterparts. The question of why these income differences persist has been the basis of research and debate in the rural development field for decades, though it is typically acknowledged that a lack of viable economic opportunities is at least partially responsible. Recent work suggests the value of natural amenities and nature-based recreation for generating jobs and income in areas with little potential for attracting more traditional forms of economic development opportunity, such as manufacturing. Swain County, North Carolina is one of these places.

For decades, the mountains of western North Carolina have attracted tourists drawn by the various recreational opportunities provided by the region's thousands of acres of public land. Western North Carolina is within a day's drive of the majority of the population in the eastern United States, and as the popularity of outdoor recreation has grown, so has the flow of people to the mountains. Seasonal home purchases are growing and businesses supporting outdoor recreation seem to be doing well as the area becomes a nationally known destination for kayakers, bicyclists, and sightseers. Many of Swain County's nearly 13,000 residents welcome this means of growth in a place that has historically been less economically developed. However, change does not come without costs. Tensions are on the rise as the Tennessee Valley Authority and the National Park Service consider decisions that will impact the county.

Setting

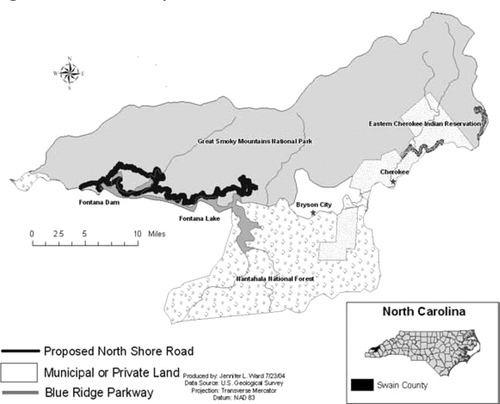

Remote Swain County is an outdoor enthusiast's dream. As of 2000, 71% of Swain County's 528 square miles was federally owned land, including parts of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway, as well as significant tracts of national forest land (figure 1). Swain County is similar in many ways to other U.S. rural counties in that it struggles with persistent economic development issues such as containing population out-migration, balancing environmental concerns with economic needs, and generating sufficient revenue to provide essential public services.

However, Swain County tends to lie on an extreme with respect to many pertinent indicators. For example, out of the thirty primarily rural counties that border the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, Swain has the greatest share of land under federal management, the largest percentage of total sales from recreation and tourism revenue, and the highest poverty rate (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service). Swain County not only tends to fall behind on the regional scale, but also when compared to the rest of the nation. For the past ten years, the county's unemployment rate has averaged 7.8% higher than the rest of the country, and during winter months regularly tops 20% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). Between 1994 and 2002, Swain County's per capita annual income averaged $10,536 lower than that of the nation (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis).

Swain County NC land use

History of Federal Land Management in Swain County

The reservoir known as Fontana Lake was created behind Fontana Dam, the largest dam in the eastern United States. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) began construction of the dam in 1942. The Tennessee River Valley was fairly remote and economically depressed, and it was believed that the region would benefit economically from the relatively cheap power and improved navigation generated by an integrated hydroelectric power system. However, the creation of this system did not come without certain trade-offs for the region. The Fontana Dam project flooded 11,000 acres, and in total 67,800 acres of land was condemned or bought from the residents of Swain and adjacent Graham County. The land acquired by the TVA to construct the dam resulted in a 16.6% loss of land area to Swain County (U.S. Tennessee Valley Authority).

North Carolina Highway 288 was an additional loss to local residents. The highway, which was flooded by the creation of the dam, provided the only access to a number of cemetery plots of the displaced families. To resolve this issue, an agreement was made between the TVA, the Department of the Interior, the State of North Carolina, and Swain County in 1943. The “1943 Agreement” included the transfer of 44,170 acres of land from Swain County to be made part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and a provision for construction of a new road to replace NC 288 (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service). The new road, known as the North Shore Road, would be constructed through the park from Bryson City to Fontana Dam “as soon as Congress appropriates the funds” (Asheville Citizen-Times). In 1948, the National Park Service built one mile of the road at Fontana Dam, and in 1970, they built 6.2 miles at Bryson City. In 1972, the National Park Service stopped construction due to concerns about environmental damage and lack of funds (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2004). The two sections are referred to as the “Road to Nowhere” since it abruptly ends without linking to a destination or other roads. The estimated $150 million necessary for the construction of the remaining 30 miles of the North Shore Road has not yet been appropriated (Citizens for the Economic Future of Swain County).

TVA Lake Level Management

Fontana Lake is a unique location that has attracted local recreators and those from bordering states for decades. Ninety percent of the land surrounding the lake is federally owned, thus development has been kept to a minimum along its many miles of shoreline. A roadless section of Great Smoky Mountains National Park borders the lake on the north, and the U.S. Forest Service manages land on the western side of the lake that contains popular mountain biking trails, a campground, and boat ramps. Water sports, including swimming, boating, fishing, and flatwater kayaking are popular on the lake. Some private businesses operate floating stores where recreators can purchase gas, ice, and other supplies. There are also several hundred privately owned houseboats on the lake, and the businesses that serve them offer delivery service and off-season storage. Spending by Fontana Lake recreators—on bait, gasoline, groceries, camping, souvenirs, restaurant meals, and dock fees—generates local income and tax revenue.

Historically, the TVA has managed its many reservoirs such that recreation is viewed as a by-product rather than its primary function. TVA draws down the water levels in the reservoir in late summer in order to prevent the flooding that could result from the large amount of rainfall during winter and spring months. In late spring, when the risk of flooding has subsided, the reservoir levels are brought up once again. However, recent concern about the tradeoff between managing the reservoir system for electricity generation and for recreation has led to reviews of TVA policy to determine if changes to current management would increase public benefits.

In the spring of 2004, after taking many concerns into consideration, TVA decided to delay the draw-down of Fontana and nine other TVA lakes until after Labor Day (Tennessee Valley Authority). Increased lake levels later in the season could mean higher electric bills for TVA customers because in order to keep lake levels up for recreational purposes, the TVA may have to sacrifice the potential to generate hydroelectric power (Tennessee Valley Authority). In an attempt to avoid increases in power costs, the minimal capacity at Fontana and the other affected lakes will be maintained from July 1st until Labor Day. Ecological concerns will also be addressed. The TVA plans to monitor dissolved oxygen concentrations and temperature with respect to guidelines set by their Lake Improvement Plan. As requested by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, they also will take special precautions to ensure minimal impact on the pink mucket mussel and snail darter fish, as well as other protected populations (Tennessee Valley Authority). Additionally, TVA has concluded that the new policy will not increase the risk of flooding in the area.

The North Shore Road

In addition to concern about Fontana Lake level management, there is also lingering controversy surrounding the North Shore Road. One remaining contentious issue is the lack of road access to cemetery plots that are located in what is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Twenty-six Swain County residents filed a suit in 1983 to enforce the 1943 Agreement and gain road access to the cemeteries. A U.S. District Court, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court all denied the citizens' right to enforce the agreement. The National Park Service responded to citizen pressure for access to the cemeteries by providing boats to ferry people across Fontana Lake, then driving them in vans along old logging roads in the Park (Snyder). However, family members of those buried in the cemeteries believe that this form of access is not sufficient and they, along with other local residents, continue to lobby for the promised road.

Despite setbacks in attempts to force funding for the road via the courts, $16 million was included in a rider to the 2001 U.S. Department of Transportation Appropriations Act for the completion of the North Shore Road. This money is currently being used to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), required under the National Environmental Policy Act for all projects funded federally or conducted on federal land. The purpose of the EIS is to assess the feasibility of construction of the North Shore Road while satisfying obligations of the federal government resulting from the 1943 Agreement (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2004). Public hearings have been conducted as part of the EIS process to solicit citizen comment on the road. During the first public comment period, over 2,500 comments were submitted, yielding a broad spectrum of responses (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2004). The EIS is expected to be complete in 2006.

The Citizens for the Economic Future of Swain County (CEFSC), made up of 255 members and founded in 2001, are opposed to the road. CEFSC drafted a bill that would settle the 1943 Agreement by compensating Swain County at least $50 million in lieu of construction of the North Shore Road. This number is based on calculations done by the CEFSC that take into account the estimated valuation of NC 288 at several periods in time. Currently, the bill has no Congressional sponsor. Supporters of the cash settlement argue that it would bring greater benefits to Swain County than the road. The investment of $50 million into an interest-bearing account would yield over $2 million each year directly to Swain County, nearly doubling its annual budget.

Supporters of the bill state that the additional funds would enable Swain County to make important improvements to the community, including better schools, infrastructure, and government programs, which would make the area a more attractive place to live. Many people favor the cash settlement, including local citizens and members of North Carolina's Congressional delegation. The Swain County Board of Commissioners voted four to one in favor of the cash settlement in February 2003 (Asheville Citizen-Times).

Supporters of the cash settlement cite other benefits; one issue regards the potential negative effects of the road on tourism. The remote setting of the area of the park where the road would be constructed currently provides a unique opportunity for hikers, campers, anglers, bird watchers, artists, and photographers, as well as scientists. The remoteness would be disrupted by the road and thus diminish the park's value to this group of visitors.

Local and national environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, have also been campaigning for the cash settlement. These groups are concerned about the potential environmental degradation that would result from the construction of the North Shore Road. In addition to the disruption of the largest portion of roadless mountain area in the eastern United States, they feel the road could also destroy wildlife habitat. Another concern is that portions of the “Road to Nowhere” built in the 1960s cut into the Anakeesta rock formation, which leached sulfidic material producing an acid capable of sterilizing aquatic life in streams (Snyder).

The Environment and Economic Development: Friends or Foes?

Throughout the past century, there has been significant conflict in the United States between the environment and the economy. This is particularly true in rural areas where natural resource extraction, such as logging, mining, ranching, and fishing, makes up a large share of local income. In Swain County, many people feel that the environmental issues brought up by outside groups such as the Sierra Club are in conflict with local interests.

One well-publicized example of this tension was the conflict between the endangered northern spotted owl and logging interests in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1990s. In this instance, the survival of a species was pitted against the economic survival of local loggers and their families. Ruling on a suit brought by environmental groups seeking to enforce the Endangered Species Act and protect the owl, a Federal District Court Judge banned the sale of new timber on 24 million acres of national forest in Oregon, Washington, and Northern California. Many people feared that this ruling would bring serious economic decline in the areas affected by the ban. Indeed, from 1988 to 1996, employment in the lumber and wood products industries in the Pacific Northwest fell 22%. However, during these same years, overall employment rose 27% (Niemi, Whitelaw, and Johnston). While many people suffered significant hardship, the end result was a potentially improved economic situation. This outcome demonstrates that the economy and the environment do not have to be at odds.

The situations in Swain County and in the Pacific Northwest illustrate two competing theories concerning the role of natural resources in economic development. The traditional model asserts that a fundamental basis of economic development is natural resource extraction and processing. Under this model, which has been predominant throughout the history of the United States, economies depend upon access to natural resources as inputs into production, and environmental protection efforts that reduce their extraction imply a loss of jobs and revenue. The second view of natural resources and economic development, referred to as progressive or environmental, views the preservation of environmental amenities and natural landscapes as an essential part of a community's economic well-being (Power). Under this theory, there is interdependence rather than a conflict between the environment and the economy. The spotted owl example illustrates that an understanding between the two theories can be reached, yielding an overall advantageous economic outcome.

Natural amenities play a significant role in economic development; one of the primary ways is through tourism. In particular, nature-based tourism is experiencing rapid growth worldwide. This type of tourism is dependent on an area's unique set of natural resources. Nature-based tourism, including fishing, hunting, ecotourism, and adventure tourism, is one way to create incentives to preserve environmental quality since the protection of natural resources is essential to the maintenance of economic gain from nature-based tourism. If the natural resource quality and character declines, tourists may decide against visiting the region.

In addition to increasing tourism, natural amenities can also lead to economic development in other ways. In a 2001 study, a group of researchers examined the relationship between specific natural amenities in rural areas, such as water, climate, and land, and the corresponding development of that area. They found that areas where their chosen group of natural amenities was present were more likely to have growth in population, income, and jobs than areas that had fewer amenities (Deller et al.). According to another group of researchers, natural amenities appeared to be the most important determinant of in-migration to rural counties throughout the 1990s (Nord and Cromartie). Additionally, Wu and Cho show that in areas where natural resources are present, income levels of residents tend to be higher.

Opportunity Costs of Federal Lands to Local Jurisdictions

A reduced tax base is another predicament that Swain County faces. Because the majority of their land area is under federal ownership, the county struggles to collect property tax revenue to fund local government services and support its economy. In Swain County, an ad valorem tax of fifty-five cents of every 100 dollars of any type of property valuation is paid to the government each year (Swain County Tax Office). However, in the case of both Fontana Lake and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, properties that make up a large percentage of the county's total area, the federal government owns the land and thus does not pay taxes on it. An example of the impact of this shortfall is the amount of money that Swain County is able to spend educating its children. In 2001–02, Swain ranked 106th of 117 districts in North Carolina with expenditures of $769 per pupil; the state average for local spending on education in that year was $1,464 with a high of $3,971 per pupil (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction).

The tax implications of federal land ownership are pertinent in many regions of the country. The federal government owns over 657 million acres of land, nearly 30% of the total U.S. land area. This means that there are 657 million acres on which state and local governments cannot collect taxes (Espey and Owusu-Edusei). Because they usually have a relatively small tax base, communities with large shares of federal land often need some additional form of aid in order to run important programs such as schools, libraries, and law enforcement that are typically financed with local property tax revenue. To ameliorate this problem, some form of revenue is transferred from the federal government, who owns the property, to the local government.

Payments-in-lieu of taxes (PILT) are one way to help ensure the economic well-being of communities that include federally owned land. Initially implemented in 1976, PILT attempts to compensate counties for lost property tax revenue. The amount of PILT money that a county receives is determined utilizing a formula that takes into account such variables as population, non-PILT governmental monies received by the county, and federal land within the county. However, some local officials as well as inhabitants of counties receiving PILT money claim that payments have been inadequate in recent years (U.S. Congress). The low amount that PILT counties have to spend on such important endeavors is exacerbated by the fact that after full payment amounts are decided, they are subject to Congressional appropriation. In 2002, counties received only 59.7% of the money authorized by the PILT program. Senate bill 511, introduced in 2003, would allow permanent full funding for the PILT program, without having to go through the appropriation process (PILT and Revenue Refuge Sharing Permanent Funding Act).

Conclusion

There is no single reason why Swain County lags behind its neighbors and the nation in economic development. Federal land ownership creates some largely seasonal jobs in tourism and related service industries. However, the overwhelming proportion of federal lands in the county means that there is little room for economic diversity within its borders. The county's remote location and mountain topography also likely contribute to its situation. Swain County's ongoing concern about its economic development is closely tied to its anxiety about federal agency decisions that will impact its natural assets.

Historically Swain County, like many other places, focused its local economic development efforts on attempting to recruit outside jobs into the area. However, recent actions suggest a shift in focus to sources of economic opportunity that are more internal to the county, such as the promotion of local entrepreneurship and expansion of existing businesses. The situation in Swain County illustrates that the perception of the potential sources of rural economic development may have changed over time. In this and other regions, many see natural amenities and nature-based recreation as potentially significant drivers of the region's economic development. The area's development woes will likely not be completely alleviated by focusing on its natural amenities. However, a concentration on its (natural) assets may be a viable alternative given Swain County's constrained options.

Questions for Classroom Discussion

- It appears as if Swain County officials and residents are interested in using recreation as a tool for economic development. What are some of the potential benefits and problems of this approach?

- Cost–benefit analysis is one of the potential tools for determining if the North Shore Road should be built. If a cost–benefit analysis of road construction were conducted, which costs and benefits should be included?

- How do equity concerns get accommodated in the policy-making process? In this case, is there an outcome that would seem equitable or fair to you?

- What role do you think native populations, environmental organizations, or other stakeholder groups should have in the North Shore Road decision? Should this issue be decided on a local level?

- Are Fontana Lake and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park public goods? What implication does this have for their management?