International Beef Prices: Is There Evidence of Convergence?†

This paper was presented at the session “Analyzing International Public Goods and Trade: Methodological and Policy Implications from Studies of Food and Mouth Disease,” organized at the Allied Social Sciences Association annual meeting in Philadelphia, January 7–9, 2005.

The articles in these sessions are not subject to the journal's standard refereeing process.

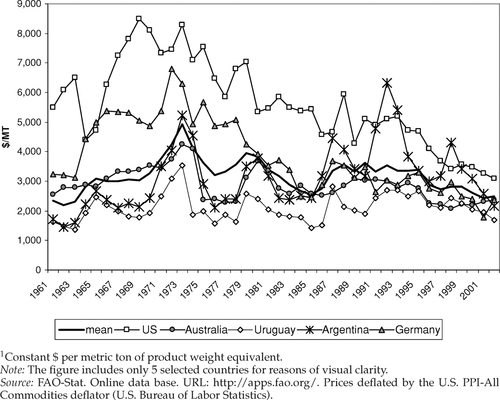

The beef export prices of different countries seem to show significant convergence over the last three decades (figure 1). Such convergence might be caused by a number of factors, including changes in commercial policy following the Uruguay Round or the erosion of the price penalty traditionally faced by beef-producing countries with endemic foot and mouth disease (FMD). The conventional wisdom is that FMD has divided the international beef market into two segments, with beef from FMD-free producers enjoying a higher price than beef from FMD-endemic producers. This segmentation is decreasing. Some producing countries have increasingly brought FMD under control and greater scientific knowledge has shown that properly processed, boneless beef from FMD-endemic countries poses little risk of contamination.

Historically, beef trade also has been strongly influenced by commercial policy. The last two decades have witnessed some liberalization in import quotas and a reduction in the use of export subsidies by major exporters. It is thus possible that the liberalization of commercial policy and/or changes in the effect of FMD have allowed beef prices to converge. If so, such convergence would probably imply significant welfare gains for consumers and producers in this important commodity market.

Export price1 of fresh beef, major exporters, 1961–2002

This paper reports the results of efforts to test whether beef prices are converging. We disaggregate beef exports into two reasonably homogeneous commodities, bone-in and boneless beef, for which data can be obtained for a significant number of countries over time. Studies utilizing beef prices often assume that beef is a homogeneous commodity. This was a reasonable assumption in the 1960s, when almost all trade was carried out in carcasses. Today, however, almost all beef is exported in the form of differentiated cuts, with roughly 85% as boneless cuts. A simple and moderately satisfactory disaggregation into more homogeneous products is that of bone-in beef and boneless beef. Beef sold as carcasses, half carcasses, and quarters are classified as bone-in beef, as are a number of rather simple bone-in cuts, most of which involve little value added in processing. Boneless cuts generally imply a higher degree of processing. Using these two commodity groups, we apply two common tests of convergence. The results support the hypothesis that convergence is occurring in each segment. We are now testing using other econometric methods. The results obtained from those tests support the results reported here, but space precludes their inclusion.

Measuring Market Integration and Price Convergence

Several recent studies have suggested growing integration between the FMD-free and FMD-endemic market segments. Dries and Unnevehr utilized correlation analysis, including Granger tests, to show that export prices in the two segments had become positively correlated post-1974, though they showed no correlation before then. They also found that Argentine export prices, which were used to represent the FMD-endemic market, appeared to be determined by U.S. prices. Hernández, Pañeda, and Ruiz used co-integration analysis to compare U.S. import prices of Australian beef with Argentine export prices, concluding that these two prices were co-integrated in the long run, but only after taking into account several atypical market disturbances. Alfaro, Salazar, and Troncoso argued that since beef prices seem to be reasonably co-integrated, sanitary barriers do not translate into segmented or independent markets. In a somewhat-related study, Diakosavvas showed that Australian and U.S. domestic beef prices were co-integrated from 1972 until 1993, but found no significant price convergence.

The studies cited support the hypothesis that beef prices between the FMD-free and FMD-endemic producers are increasingly co-integrated, but provide little evidence of price convergence. Of course, prices may differ in levels even if they tend to move together, with price differentials reflecting market barriers, transactions costs, or quality differences. Thus, we believe our analysis of price convergence provides additional important information.

We introduce three methodological improvements. First, the use of Argentine prices to represent the FMD-endemic price in two of the studies cited casts some doubt on the usefulness of their results. Since 1985, Argentina's exports under a preferential basis in the European Union (EU) have a significant effect on that country's average export price, so that neither the movements nor the level of Argentina's price is representative of FMD-endemic countries. Second, past studies have emphasized pair-wise comparisons between countries rather than among a group of countries. It is reasonable to believe that methodologies utilizing prices from a group of countries are likely to be less dependent on the particular situation of one or two countries. Third, a number of problems arise from the use of the aggregate export price, which is commonly determined by dividing the income from all exports by the quantity of beef exported. The aggregate export price of a country is, therefore, sensitive to the export product mix (proportion of high-quality versus low-quality beef exported) and to the market composition (proportion of beef exported to protected markets at prices above a competitive level). Considering bone-in and boneless beef as two separate products is one step in treating this problem. It would be desirable to disaggregate further, but this cannot be done for a longer period with the data available.

Methodology and Data

We identified seventeen countries that each accounted for at least 1% of the international beef market in 2002. Collectively, they accounted for 90% of world beef trade. Using annual data, we calculated the implicit beef export price for each country's beef products using the respective value of exports, divided by the total quantity of exports, as reported by FAO (http://apps.fao.org/default.jsp). Each price series was deflated using the U.S. Producer Price Index (PPI) for all commodities. We utilized these data to test for price convergence in 1961–2002 and 1980–2002. Substantial changes occurred in the international beef market after 1980 that justify a separate analysis for that period. We also obtained monthly data for a subset of seven exporters for 1990–2002, and tested for price convergence using this country subset. Sources of monthly data were: the U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistics Canada, the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE), the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), the European Union EUROSTAT database, the Brazilian Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior, and the Uruguayan Instituto Nacional de Carnes.

We defined price convergence as a shrinking divergence over time in the prices obtained by the principal beef-exporting countries. We tested the hypothesis of convergence using two variations of an approach previously utilized to analyze changes in price dispersion (Cecchetti, Mark and Sonora; Gaulier and Haller; and Goldar, among others). One test utilized the mean of the absolute price differentials and the other utilized the standard deviation of absolute price differentials. In each case, we first calculated the weighted mean price for each year for the countries included in a group, using each country's quantity share of the groups' total exports as weights. We calculated the annual price differential for each country as the deviation from the group mean. We next calculated the annual mean of the absolute price differentials and the annual standard deviation of the price differentials, dividing each observation by that year's mean price to adjust for any change in the price level over time. We then fit a linear trend to each of the series of annual observations. The null hypothesis was that the estimated trends would be negative, reflecting a tendency for the mean or the standard deviation of the differentials to decline over time.

We analyzed convergence for the entire set of countries and for several subsets to determine whether any of the results appeared sensitive to the particular set of countries chosen. For each analysis, we utilized both (i) the mean sum of the absolute price differentials and (ii) the standard deviation of the price differentials. We applied each test to the prices of (a) bone-in beef and (b) boneless beef, for each period of data availability.

The country sets were:

- Group 1:The seventeen principal exporters, each accounting for at least 1% of 2002 world fresh-beef exports, were: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium-Luxembourg, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Spain, United States, and Uruguay;

- Group 2:The European exporters included in Group 1: Austria, Belgium-Luxembourg, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, and Spain;

- Group 3:The eight largest exporters over the whole period: Group 1, excluding Poland and taking the EU as a single country with intra-bloc trade excluded. (Data for the EU are available only after 1978);

- Group 4:Four major grass-fed exporters: Australia, New Zealand, Uruguay, and Brazil. The first two countries have been always FMD-free, whereas Uruguay and Brazil have almost always been FMD-endemic. This set probably provides the best test of convergence between the FMD segments.

Results

Table 1, part A, contains the results for tests (i) and (ii) applied to the prices of boneless and bone-in beef, using annual data for 1961–2002 and 1980–2002, for the four sets of countries. Price convergence (P < 1%) is observed for the whole set of exporters and the European exporters (country sets 1 and 2), for bone-in and boneless beef, in both periods, except for one case where the mean of price differentials is not significant (country set 2 for the second period—such prices had already largely converged). Price convergence is also observed in country sets 3 and 4, for bone-in beef and in some cases for boneless beef, particularly for 1980–2002. The prices of the largest exporters (country set 3) also show convergence for the prices of bone-in and boneless beef in both periods when the test uses the standard deviations of price differentials, but not when the test uses the mean of the absolute price differentials. Further, when these same tests are applied to the prices of boneless beef, the results from both tests support divergence in 1961–2002 and indicate no significance in 1980–2002. The prices in matched set of FMD-free and FMD-endemic country prices (country set 4) show convergence for both types of beef and in both periods, except for the test using the standard deviation of price differentials for boneless beef in 1980–2002, which is insignificant. This set of results suggests that the price differential attributed to FMD has shrunk.

| 1961–2002 | 1980–2002 | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Annual Data | ||

| Group 1 (17 Countries) | ||

| Bone-in | ||

| Mean APD | C* | C* |

| SD | C* | C* |

| Boneless | ||

| Mean APD | C* | C* |

| SD | C* | C* |

| Group 2 (10 Countries) | ||

| Bone-in | ||

| Mean APD | C* | C* |

| SD | C* | C** |

| Boneless | ||

| Mean APD | C* | C* |

| SD | C* | C* |

| Group 3 (8 Countries) | ||

| Bone-in | ||

| Mean APD | NS | NS |

| SD | C | C |

| Boneless | ||

| Mean APD | D | NS |

| SD | D | NS |

| Group 4 (4 Countries) | ||

| Bone-in | ||

| Mean APD | C* | C* |

| SD | C* | C* |

| Boneless | ||

| Mean APD | C* | C* |

| SD | C | NS |

| B. Monthly Data | ||

| 7 Major Exporters | January 1990–December 2002 | |

| Bone-in | ||

| Mean APD | C* | |

| SD | C* | |

| Boneless | ||

| Mean APD | C | |

| SD | C* |

- Notes: C* and C correspond to Price Convergence with P < 1% and 1% < P < 10%, respectively, while D and NS correspond to Price Divergence with 1% < P < 10% and No Significance, respectively.

Table 1, part B, contains the results for tests (i) and (ii) carried out using monthly data for 1990–2002 for Group 3 (less Argentina, for which monthly data were not available for the whole period), again for both bone-in and boneless beef. The monthly data provide a significantly larger number of observations for the regressions, although for a shorter time period. The results from tests (i) and (ii) provide strong evidence of price convergence for bone-in and boneless beef in 1990–2002. The same tests using annual data for the longer period for the eight largest beef exporters did not show convergence. Note that the use of annual data for 1990–2002 produced highly similar results, with and without the inclusion of Argentina, as did the monthly data. It thus seems clear that price convergence has been stronger in the 1990s. This important result indicates that significant “efficiency” gains have been continuing in the most recent period among the largest exporters, which jointly account for a large share of beef exported.

Conclusions

The world beef market has changed substantially over the last forty years, involving expansion in total exports, the emergence of important new exporters and importers, and the gradual decline in the importance of others. As part of this process of change, we find consistent evidence that beef prices have converged, primarily during the last two decades. The results from the test using the annual prices of countries in group 4, suggest that the FMD price differential has narrowed.

We suspect that the liberalization of commercial policy has also been an important cause of the apparent, ongoing convergence of international beef prices. Our qualitative examination of the data shows that the greatest divergence among market prices has been the result of several exporting countries having had preferential access to several strongly protected markets. For example, the United States emerged as an important beef exporter largely in response to the preferential access it received in the Japanese and then the South Korean markets. The United States received prices in these markets that were much higher than the United States could have received in other markets. However, as Japan and South Korea liberalized their markets, imports from Australia and New Zealand competed with imports from the United States, gradually driving down prices until they more closely approximated prices in less-protected markets (figure 1). Another important example of commercial policy liberalization is the EU's decision to reduce the magnitude of its subsidies on beef exports to the “Atlantic” market. Thus, although the world beef trade remains impeded by sanitary and commercial policies, these appear to have diminished in the last two decades, bringing about considerable global economic benefit to producers and consumers of beef.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ricardo Vernazza for research assistance and Brian Fisher, Peter Gardiner, Ralph Lattimore, and Roberto Vasquez Platero for their assistance in obtaining the data used. Lovell Jarvis thanks the Giannini Foundation for research support.

The annual data used in this paper are taken from United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, and are publicly available at http://apps.fao.org/default.jsp. The monthly data used were obtained from sources in the respective countries, some of which charge a fee for a customized data set. The U.S. and Brazil data are accessible free of charge. Monthly data from other countries must be obtained from the original source.