Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Industries: Market Expansion or Outsourcing?†

This paper was prepared for presentation at the Principal Paper session, “Outsourcing and Foreign Direct Investment: Boon or Bane?” Allied Social Sciences Association annual meeting, Philadelphia, January 7–9, 2005.

The articles in these sessions are not subject to the journal's standard refereeing process.

The issue of outsourcing has been a hot topic (Marchant and Kumar), especially in this past election year. Numerous television programs, news stories, and editorial pages have been devoted to the subject. At the heart of this debate has been the effect of investment of U.S. firms overseas (foreign direct investment or FDI) and the assumed correlation of this with job losses in the United States (popularly called outsourcing). While this certainly may have some validity in certain industries, the assumed correlation is not a universal truth (Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter). This paper examines the relationship between FDI and domestic employment with a focus on two case industries—food manufacturing and textiles.

Types of FDI

Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter define two general types of FDI, each with differing motives and effects. First, horizontal FDI is used when trade barriers, transport costs, etc., are high and the U.S. firm invests in production facilities at both home and abroad, with each production facility serving its local market. Vertical FDI, in contrast, is typically employed to take advantage of factor-cost differences. The classical example is where, for example, research and development (R&D) and advertising (human capital intensive) take place in the United States while production (manual labor intensive) occurs in another country where labor costs are low. In common parlance, vertical FDI is “outsourcing” while horizontal FDI is “market expansion” or “tariff jumping.” According to Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter both types of FDI take advantage of scale economies of headquarter activities, such as R&D and advertising, and achieve more efficient global production. But the two types of FDI differ in their effects on factor incomes within and across countries. In this study, we argue that these two types of FDI also have different impacts on employment in the home country.

Home Country Effects

The positive effects of FDI on the host country have been documented (Borensztein, DeGregorio, and Lee; Dollar; Ram). However, very few studies have addressed the effects of FDI on the home country. Several studies have examined the relationship between FDI and exports for the home country (Bergsten, Horst, and Moran; Lipsey; Lipsey and Weiss 1981, 1984; Blomstrom; Pick, Gopinath, and Vasavada; Marchant, Cornell, and Koo).

A few studies have focused on the effects of FDI on U.S. employment (Brainard). While there is some competition between manufacturing firms' employment at home and abroad, the degree of substitution is low in the aggregate. Markusen and Maskus stress that there are no universal relationships between production abroad by a firm or a country's firms and exports by investing firms, a finding this paper supports. Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter and Markusen and Maskus suggest that the overall effect depends on whether the foreign operation's relationship with home operations is horizontal or vertical.

Horizontal and vertical FDI may have different effects on domestic employment. As we know, firms usually engage in both headquarter services and production (Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter). First, both horizontal and vertical FDI have positive effects on domestic employment in headquarter services, which is human capital intensive and usually located in developed countries, such as the United States. Both types of FDI will increase the production and sales of multinational firms, so more headquarter activities will be needed. As a result, the employment in headquarter services in the home country will rise. Second, vertical FDI has a negative impact on domestic employment in production while horizontal FDI has little (or even positive) effects on domestic production employment. When the FDI is vertical, multinational firms move part or all of their domestic production to foreign countries where labor (and other) costs are lower. But, horizontal FDI usually replicates production plants in foreign countries to serve customers in those countries and their neighboring regions so that it has almost no effect on employment in production in the home country.

The total effect of vertical FDI on domestic employment will depend on the relative magnitudes of its positive effect on employment in headquarter services and its negative effect on production employment. In the real world, the number of jobs eliminated by the shift of production abroad is usually much larger than the number of new jobs in headquarters services created by more demand for these activities. Thus, vertical FDI usually reduces total domestic employment. On the other hand, horizontal FDI will increase total domestic employment because it creates more demand on headquarter activities at the home country and has little or no effect on domestic production employment.

This study highlights two case industries—food manufacturing and textiles. Food manufacturing is presumed to practice horizontal FDI and textiles vertical FDI. If theoretical predictions in previous literature and our analysis are correct, we expect to see that FDI for food manufacturing has no, or perhaps even a positive, effect on U.S. employment in the sector. In contrast, FDI is expected to have a negative impact on U.S. employment in textiles.

Food Manufacturing

FDI has become the leading means for U.S. processed food companies to participate in international markets. Affiliates of U.S.-owned food processing companies had $30 billion in sales throughout the Western hemisphere in 1995, nearly four times processed food exports, according to Bolling, Neff, and Handy. They find evidence that, in the aggregate for the 1990s, trade and FDI were complementary—not competitive—and FDI was a means of accessing international food markets. Income in most countries has grown sufficiently to support growth in affiliate sales and U.S. exports to satisfy strong demand for a wide variety of processed foods (Vaughn; Handy and Henderson).

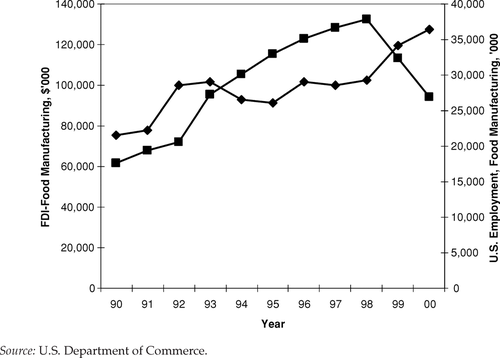

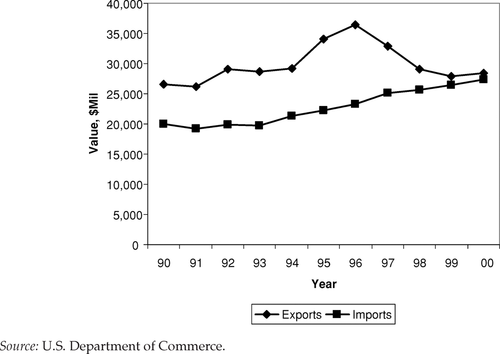

We begin by graphically analyzing the trends in FDI and employment in food manufacturing. Figure 1 shows there was an overall increase in the level of FDI by U.S. food manufacturing firms in 1990–2000. At the same time, there was also an increase in the level of U.S. employment in food manufacturing. Exports have been relatively flat and imports are on a slightly increasing trend (figure 2).

Taken together, these data suggest a direct relationship between U.S. employment and FDI by U.S. manufacturing firms. A reduced-form model of U.S. food manufacturing employment tends to support this conclusion (table 1). Here, U.S. food manufacturing employment is regressed against sales by foreign affiliates of U.S. food manufacturing companies and domestic sales of U.S. companies (all variables in log form). Results suggest that as foreign sales increase, U.S. food manufacturing employment increases (although the elasticity is quite small at 0.04). This result is consistent with the argument that FDI in food manufacturing is horizontal, and is also consistent with the findings of Marchant, Cornell, and Koo that FDI in food manufacturing is complementary with U.S. exports (with increases in exports leading to greater U.S. employment). From a broader perspective, these results support the argument that FDI in food manufacturing is not leading to “outsourcing.” Rather, U.S. manufacturers are using FDI as a market penetration strategy (Solana-Rosill and Abbot) by establishing a local presence and producing for local markets.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | t-Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food manufacturing | |||

| Intercept | 6.6740** | 0.3906 | 17.09 |

| Foreign salesa | 0.0396** | 0.0120 | 3.29 |

| Domestic sales | 0.01893 | 0.0430 | 0.44 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.85 | ||

| Textiles and apparel | |||

| Intercept | 11.1330* | 5.4554 | 2.04 |

| Foreign salesa | −0.3087** | 0.1071 | −2.88 |

| Domestic sales | −0.0941 | 0.5361 | −0.18 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.44 |

- a Sales of foreign affiliates of domestic (U.S.) parent companies.

- * Statistically significant at the 0.10 level.

- ** Statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

U.S. employment in food manufacturing and foreign direct investment by U.S. food manufacturing firms, 1990–2000

Real value of U.S. food manufacturing exports and imports, 1990–2000

Textiles

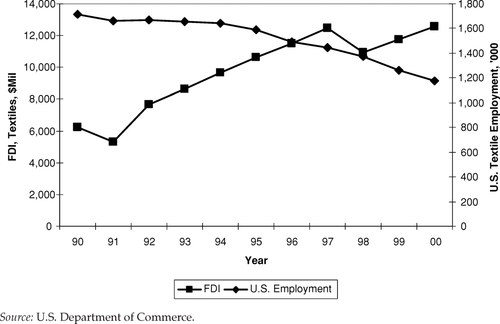

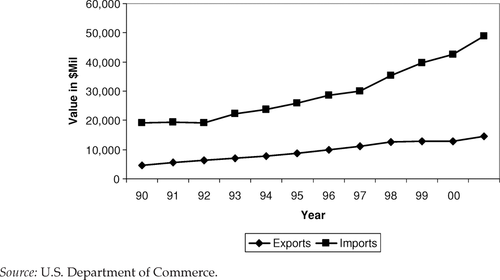

Textiles provide a much different picture of the impacts of vertical FDI on U.S. employment. Here, we see definitive decreases in U.S. employment with a corresponding upward trend in FDI (figure 3). Further, we see that imports are increasing more rapidly than exports (figure 4). The rapid increase in FDI, the decline in U.S. employment, and the corresponding increase in U.S. imports leads one to hypothesize that U.S. FDI in textiles and apparel is leading to a displacement of U.S. labor—or, labor is being “outsourced” in textiles.

There are some indications that outsourcing has led to a shift toward more capital- and skill-intensive production in the United States, as particularly unskilled-intensive production has been allocated to affiliates in developing countries (Kravis and Lipsey). Domestic apparel production in the United States accounted for only 39% of the total wholesale market in 1997. Imports supplied 46% and outward processing or outsourcing trade supplied 15%. Employment is down over the 1990 through 2003 period by 38–40% in both textile and apparel manufacturing (McMillan, Pandolfi, and Salinger).

U.S. employment in textiles and apparel manufacturing and foreign direct investment by U.S. textile firms, 1990–2000

Real value of U.S. exports and imports of textile and apparel products, 1990–2000

Table 1 also presents results from a similar regression for textiles performed for food. Here, we see that the impact of FDI in textiles has an inverse and statistically significant relationship with U.S. employment in textile manufacturing. This result suggests, as hypothesized, that FDI in textiles is vertical, leading to outsourcing of U.S. labor in textile production.

Discussion

The differing results between the two sectors observed here are not surprising when the motivations of horizontal and vertical FDI are considered. First, textile and apparel production are more labor intensive than food manufacturing, and the labor that is required is likely more low skilled for textiles (and, especially, apparel). Thus, it is reasonable to suspect that textile manufacturers would be more interested in capturing factor-cost differentials on the labor component, while retaining headquarters activities in the United States. For food manufacturing, tariff structures are more complicated, transport costs are higher (especially for more perishable items), and local dietary customs and demands make vertical FDI less appealing.

Thus, like Markusen and Maskus, we find that it is difficult and misleading to generalize the impacts of FDI on domestic employment. The impacts and motivations of FDI are driven by economic fundamentals. Political rhetoric and sound bites have only served to confuse public understanding of this complex issue.