Case Studies of Direct Marketing Value-Added Pork Products in a Commodity Market

Abstract

Differentiation and branding of fresh pork products have created interest in the potential for swine producers to invest further up the pork supply chain to capture a greater share of the consumer's dollar. However, the ultimate success of producer-owned ventures will depend on their ability to identify market opportunities and execute merchandising strategies to maintain sales of a perishable and seasonally variable pork product in a commodity market environment. To better understand the competitive issues in pork marketing on a small scale, three firms already engaged in direct marketing of fresh pork products are examined and reported as case studies.

Interest in value-added pork production is illustrated by recent producer initiatives, including Pork America, Heritage Farms in Illinois, and Prairie Farmers Cooperative in Minnesota among others. Each of these proposals includes either potential investment in pork slaughter and further-processing facilities by hog farmers (vertical integration) or business arrangements to maintain ownership of the pork product through the production chain to the final consumer (vertical coordination). While the success of these value-added ventures will depend on operational and financial efficiency, they must also address the issue of how they will compete with existing pork production firms. In economically defined commodity markets, competitiveness is associated with cost efficiency since all firms are by definition price takers. Therefore, by investing in value-added ventures, producers must believe that either they can be more cost efficient than existing competitors or they can differentiate themselves or their product from the commodity market to command some competitive niche that insulates them from sole reliance on cost efficiency.

This paper's objective is to describe how three existing small-scale direct pork marketing enterprises have managed to differentiate themselves to create a competitive niche. The paper first presents the research literature regarding the competitiveness and structure of the pork industry, providing the conceptual framework upon which evidence from the case studies is built. The results of the case studies are presented in three topics related to developing competitive niches in a commodity market. These are differentiating: (a) product mix and pricing; (b) supply chain management to fit a competitive niche; and (c) advertising and promotion.

Previous Research on Pork Market Competitiveness and Differentiation

Previous research provides a starting point to gain insight into the competitive nature of pork markets and the potential to differentiate products to suggest whether these ventures hold promise. Holloway examined the competitive behavior of farm-retail margins for several food products for 1955–1983 and found that any departures from competition regarding pork were small and insignificant. Schroeter and Azzam more specifically considered the marketing margins for pork farm/wholesale prices (relating to the issue of pork slaughter operations' competitiveness) for 1972–1988 and found that “the farm/wholesale margins for pork were quite consistent with competitive performance in the 1980s.” Given the evidence that pork markets are competitive, this suggests that farmers entering value-added ventures should expect to be price takers as described by competitive market theory.

Most value-added ventures proposed are small-scale relative to the existing slaughter and processing firms. Several studies have examined evidence of economies of size in pork markets. Paul tests for evidence of imperfect competition in the meat sector considering factors such as technical change, international trade developments, and economies of scale. Results of this study suggest that any indications of market power are closely related to associated scale economies. Hayenga provides some insight into the scale economies of efficient pork slaughter plants and reports that average industry costs decline as volume and market shares of the largest firms increase. MacDonald and Ollinger also provide evidence that large hog slaughter plants (>1,000,000 head slaughtered per year) can deliver pork products at costs 2–3% less than medium-size plants (1,000,000 > head slaughtered per year > 50,000) and 10% lower than small plants (<50,000 head slaughtered per year). These studies add to the evidence that pork markets are competitive and that economies of scale exist. This suggests that producers investigating value-added investments on a small scale may have a difficult time competing on a cost basis implied by competitive markets.

Another fundamental issue is whether incentives for vertical integration exist. The conceptual literature on vertical integration (e.g., Perry) suggests that determinants of vertical integration include technological complementarities, transaction cost economies, and/or market imperfections. A few recent studies describe the incentives and implications of vertical integration in the pork industry. Martinez, Smith, and Zering describe motivations related to asymmetric information (sorting and measuring), asset specificity (single-use barns), and overall reduced transactions costs. Lawrence, Schroeder, and Hayenga report the motivations and extent of vertical coordination in the pork and beef industries. The responses to producer motivations for pork coordination included ensuring shackle space, ensuring quality premiums, reducing price risk, and reducing search costs. Packers cited analogous motivations for coordination.

While these studies suggest there may be real transaction cost-based merits for vertical coordination in the pork industry, they do not provide insight into how this might be used to the advantage of small-scale value-added ventures. In particular, it might be hypothesized that the transaction cost savings of vertical integration may be even greater for large-scale operations where search costs and information asymmetry, for example, increase with larger procurement bases. The following case studies, however, provide an illustration of how small-scale firms have found ways to capture vertical economies and use them to their competitive advantage.

The possibility still remains that farmer-owned, value-added ventures may compete based on differentiating their pork products from commodity products. A few recent studies provide insight into the potential for differentiation by examining consumers' responses to attribute differences and branded meat products. Hui, McLean-Meyinsee, and Jones ranked meat attributes among a sample of Louisiana and Texas consumers and found the preferred attributes were freshness, taste, appearance, USDA label, no chemical additives, tenderness, low fat, low salt, low cholesterol, and price. The relatively low ranking of price may indicate that it is not the only purchase decision factor and that consumers might be willing to pay for differentiated meat products. Boland and Schroeder examined the marginal value of quality attributes for beef products produced by a specific producer organization. Their results showed that consumers value some attributes differently than aggregate market signals. These studies suggest that although pork and beef are viewed as a commodity product in aggregate, consumers may be willing to pay for some differentiated attributes.

Other than specific quality attributes, value-added producers may seek to differentiate their product and achieve higher prices through branding and promotion. Brester and Schroeder evaluated the impact of both generic and branded advertising on meat demand and found that advertising was an important factor. They found that branded pork advertising's impact was both positive and significant. This suggests that value-added cooperatives could develop branding and advertising programs to differentiate themselves in the market and allow them some modest ability to compete beyond the concept of price takers minimizing costs.

In summary, previous research seems to suggest that farmers' value-added ventures will need to compete on the footing of the commodity pork market that clearly exhibits economies of scale. The bulk of the research results (except Boland and Schroeder) are drawn from aggregate market data, which often assumes a single market price and quality, precluding insights into how firms might differentiate themselves in a competitive market. Still, the most compelling evidence for producers considering value-added investments is likely the fact that small-scale, value-added ventures exist even in this broader competitive environment. The objective of the following case studies is to describe how existing small-scale value-added pork firms compete in a broader market described in research as competitive and exhibiting economies of scale.

Case Methodology

Given the focus on direct marketing and value-added competitiveness, there were only two criteria for candidate selection: firms had to be engaged in multiple stages of pork production and they had to directly retail pork products to consumers. The National Pork Board identified seven candidate operations through their contacts with state Pork Producer organizations. Of these, five met both criteria and two declined to participate on the basis of proprietary information.

Case participants were originally contacted and sent a summary of questions at least one month prior to a scheduled site visit by two interviewers. This allowed the participants to prepare for the line of questioning and to compile documentation that might facilitate the data collection process. Site visits were scheduled for two business days when the firms would be operating so their actual production and marketing activities could be observed. Two-day visits were scheduled so that the evening of the first day could be used to review information and formulate follow-up questions for the second day.

Case Participant Introduction

The three cases illustrate distinct aspects of marketing and competitiveness. Table 1 summarizes how each firm customizes its approach to competitive differentiation. Further details are available in the complete case studies (Buhr 1999a).

| Strategy | Gordito's | Nahunta | The Egg & I |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiating product mix and pricing |

|

|

|

| Differentiating supply chain fit |

|

|

|

| Differentiating advertising and promotion |

|

|

|

Gordito's Meats

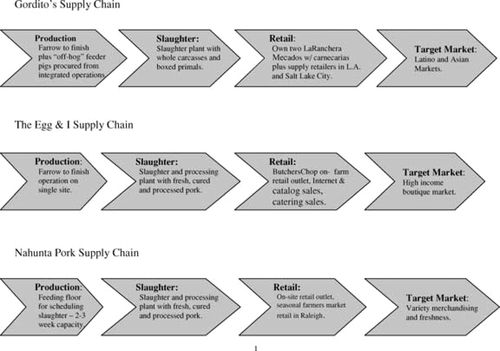

Located in Ogden, Utah, just north of Salt Lake City, Gordito's Meats operates within a small swine production region. In the early 1990s, the closing of Trimiller Packing, the only local processor, and the entrance of Circle Four Farms created a squeeze on existing Utah hog producers from larger, more operationally efficient production systems and a lack of viable markets. In response, Gordito's Meats was formed when a group of pork producers teamed with two brothers with experience marketing to Latinos in the Salt Lake City area. One had been conducting door-to-door sales of fresh pork to Latinos in the Salt Lake City region and the other owned and managed a small Latino grocery store (mercado) in Provo, Utah. They observed that the Latino pork consumer was under-served in terms of both the mix of products to suit their cooking styles and the availability of a reliable supplier. Gordito's current production operations include hog finishing, one slaughter and pork processing plant, shipping and two retail stores (figure 1).

The Egg & I Pork Farm

The Egg & I Pork Farm is located in New Milford, Connecticut, a scenic small colonial community located about one hour from New York City. Connecticut ranks fourth smallest in total hog production, and is densely populated with environmental and land constraints to expansion. However, Connecticut ranks fourth in household median income ($43,535/year), providing a very strong demand base willing to pay for The Egg & I 's experiential marketing strategy. The operation now consists of a finishing floor for hogs, a slaughter plant, a processing facility with smokers, cookers, and packaging and a retail store (the ButchersChop), all located on a single site.

Comparative overview of participants' supply chains

Nahunta Pork Center

Nahunta Pork Center is located at a country road intersection in Nahunta, North Carolina. North Carolina is the second largest hog-producing state, in sharp contrast to the market environment of Gordito's and The Egg & I. Yet, Nahunta Pork Center has continued to grow since the 1950s and plans to double its slaughter and marketings within three years. At the time of the site visits, Nahunta slaughtered about 40,000 head per year. Nahunta no longer produces its own hogs, but does include a large “feeding floor” in which hogs may be kept for two to three weeks to manage flow into the slaughter plant and retail operations. While the other two cases have specifically targeted their overall market strategy to consumer niches, Nahunta provides an excellent example of competitiveness simply by differentiating their merchandising strategy. Nahunta consists of a slaughter plant, processing plant, and a retail store.

Differentiating Product Mix and Pricing

All studies previously cited regarding price competitiveness were completed using aggregate price data for pork. However, once the hog is slaughtered, there are multiple product forms that emerge from the broad categories of whole carcasses, carcass primal cuts and retail, or portion cuts. The case participants illustrate how managing final product mix and yields in a broader competitive price environment can be used as an effective competitive strategy.

Gordito's Product Differentiation for Latino Markets

Gordito's Meats is founded on serving the Latino pork market. The company began by selling whole, unsplit, skin-on, and head-on carcasses to Latino grocery markets that fabricate portion cuts to meet costumer demand. Whole carcasses are in demand because the cutting differences of portion cuts for the Latino consumer are impossible to create using conventional boxed primals (separated hams, loins, shoulder butt and picnic, ribs, and bellies). For example, cross-sectioned spine bones are frequently used for stewing (e.g., pozole) by Latino cooks. In most plants, whole spines are destroyed once the carcass is split in the first step in carcass fabrication. By processing and delivering whole carcasses, Gordito's keeps processing costs minimal while allowing them to meet their customers' demands better than other wholesale pork products. Selling whole carcasses eliminates the need to merchandise individual primals and portion cuts with differing seasonal demands and simplifies pricing strategy. Gordito's uses USDAs reported composite pork cutout value for pricing carcasses. This recognizes that their customers are highly price sensitive and likely would sacrifice their preferences if Gordito's products were higher than competing substitutes. It is also consistent with previous research regarding the competitiveness of the pork market chain.

As Gordito's customer base grew, some demanded primal products rather than whole carcasses. The result of offering boxed primals is mixed. On the positive side, it reinforces Gordito's commitment to customer service and strengthens their relationship with their customers. Shipping boxed primals also is cheaper than carcasses. On the negative side, the change to primals necessitates merchandising primals with their differing seasonal demand profiles. To circumvent some of this merchandising difficulty, Gordito's developed prepackaged, cubed, and injected fresh pork cuts in vacuum-packed bags, which are intended for carnitas (fried pork in tortillas). Gordito's found that injecting the meat with a sodium phosphate solution substantially reduced the shrink from deep-frying pork for carnitas. Price and product yield data provided by Gordito's shows that the gross revenue per hog for pork shoulder steak alone is $21.98 (11 pounds per hog priced at $1.99/lb). In comparison, the cubed and injected pork shoulder meat provides gross revenue per hog of $24.90 (10 pounds per hog for $2.99/lb). A complete breakdown of a pork carcass by Gordito's retail butchers, associated retail prices, and a market analysis of the Latino pork consumer is published in Buhr (1999b, 1999c) and Buhr and DiPietre, respectively.

Nahunta Pork: Differentiation through Product Variety

Nahunta offers eighty-five distinct pork cuts and the style of cuts varies by seasonal demand. As in most parts of the country, December, January, and February are difficult times to sell ribs because of their close association with grilling. Although Nahunta offers barbecue ribs in winter, they also fabricate the loin to include the rib bones in a unique cut. The loin is cut into 6-inch roasts with the ribs attached. Rather than crosscut as done for bone-in chops, the roast is cut longitudinally along the ribs. This exposes the bright pink meat portion of the loin and leaves the ribs on both sides of the sliced open loin. Hence, the ribs are moved along with the loin and retails for $1.99/lb. In comparison, barbecue ribs sell for $0.99 per pound and the boneless loin roast sells for $1.99 per pound. With no trim loss, the weighted average value of the two separate cuts is lower than the combined cut. Nahunta reports the total quantity of sales is lower with this single cut in the winter than the total of the two cuts in the summer. However, this matches their lower overall pork demand and hog slaughter levels in the winter and creates added revenue versus continuing to market the ribs and loins separately.

Part of Nahunta's differentiation strategy is to keep products uniform in the package. For example, Nahunta markets end-cut pork chops for $0.99 per pound and center-cut pork chops for $1.59 per pound. A typical grocer is not likely to differentiate the similar cuts, creating a lack of uniformity in the customer's eyes and likely resulting in a discount. On the same day as the case visits, Food Lion in Goldsboro had a package of mixed chops selling for $1.19 per pound. Although it was not possible to determine the total value the uniformity created (this requires cut yield information), Nahunta explains that their average price would be approximately $1.29 per pound for the two cuts if aggregated by weighting them to the yield from the loin. Hence, they manage a slightly higher price and again create a competitive strategy by providing uniformity in packaging.

Gordito's and Nahunta illustrate how small-scale value-added pork firms are able to differentiate products to gain some advantage in the commodity market. Although both price products according to market conditions (consistent with operating in a commodity market), they are able to maintain their market sales volume and revenues by developing products otherwise unavailable to their customers while at the same time maximizing joint product yields.

Differentiating Supply Chain Management to Fit a Competitive Niche

A second key insight of previous studies is that there are large economies of scale to hog slaughter and pork processing. For example, Hayenga reported that variable costs for pork slaughter and processing by double shift plants ranged from $16–20 per head. In comparison, Gordito's reported the cost of slaughter averaged $20–25 per head for the 800 head per week operation. Nahunta reported total direct costs of approximately $60 per head from slaughter to final retail cuts, and the Egg & I reported slaughter costs of approximately $20 per head. Given this comparison, the case study operations clearly are not cost competitive with the operations of larger plants. However, each of the case firms has managed its integrated supply chain to “fit” a niche and overcome the cost handicap.

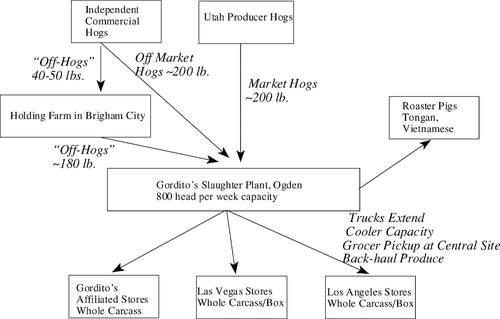

Gordito's Manages Hog Supplies to Fit Slaughter

Gordito's began by marketing only seven hogs in their initial sale. However, after their first six months of operation, Gordito's was slaughtering 100 head per week, orders were steady, and they reached the custom slaughter capacity of two contract slaughter plants. The firm risked irreparably damaging their hard-won customer relations if they could not meet orders and decided to invest in a plant with a slaughter capacity of approximately 800 head per week. This was Gordito's first investment in a major fixed asset. The plant investment changed their entire production strategy from providing hogs when orders were filled to gaining orders to maintain the slaughter capacity of the plant—moving them into a more supply chain-driven merchandising problem (figure 2).

As orders grew, Gordito's not only outstripped packing capacity, but also the daily supply of hogs from growers for slaughter. To further grow the enterprise, Gordito's began to source pigs from a nearby large integrated production system. Although the integrated operation had contractual agreements to supply market hogs to other processors, they faced the issue of what to do with “off-hogs” (hogs that have skeletal problems, lag in growth, or have other nonconformities). However, it was in the best interest of the integrator to remove the hogs from their operation when they were shipped to their grow-finish facility, or typically when the pigs reached 40–50 pounds. Therefore, Gordito's invested in a holding farm and finishing floor to feed the off-hogs until ready for slaughter in their plant. Currently, this system has the side benefit of enabling Gordito's to control pig flow to match order variability over a longer time frame than they can manage perishable pork products. This longer-term supply chain management solution is feasible partly due to their market niche. The Latino customer base is highly cost sensitive, but not as sensitive to quality issues and prefer a hog weighing about 180 pounds. Therefore, the increased costs of feeding off-pigs and the risk of them not performing to much higher weights (conventionally 260 pounds) is somewhat offset by the reduced time on feed and the willingness of their customer to accept more size variability in the final carcasses.

Gordito's supply chain coordination

Gordito's Manages Fit in Distribution and Retail

A significant aspect of Gordito's success lies in managing distribution and retail as part of their supply chain. In addition to supplying their own stores in and near Salt Lake City, Gordito's delivers to stores in Los Angeles, requiring investment in refrigerated trucks. A cold storage constraint in the packing plant was also overcome by parking a refrigerated semi-trailer in the plant's parking lot. Carcasses are moved into this trailer once they have been properly chilled and are hauled to Los Angeles when those orders are complete. This system increases the capacity of the plant available for local orders, overcoming some of the capacity constraint, and is a highly cost-effective form of storage. When the shipment arrives in Los Angeles, the semi-truck is parked in a central location near the customers' stores and the grocers pick up their orders. To further reduce shipping costs, the truck back-hauls fresh produce from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City. The Latino grocery stores served by Gordito's tend to be small, typically averaging 1,000–1,500 square feet and serving only the surrounding neighborhood. These stores are typically treated as residual demand for the commercial supply and distribution chain but are the core clients of Gordito's Meats. Large-scale distribution chains will often not compete as aggressively for these markets, which enables Gordito's to maintain their customer base.

Nahunta Pork Center's Real-Time Product Management

Nahunta illustrates creating a competitive advantage by capturing the efficiencies of real-time inventory control in their supply chain. This is best shown by how Nahunta manages their sausage production and sales. On average, Nahunta sells approximately 10,000–15,000 pounds of sausage per week and during periods of high seasonal demand, they sell 30,000–40,000 pounds weekly. In fact, one retail employee is dedicated to sausage sales. The day the research team visited (Thursday), Nahunta sold 4,000 pounds of sausage. This volume was beyond expectations for the day, and at approximately 3:00 p.m., the sausage maker reported needing to have more sows slaughtered to the plant manager. On Friday morning, several more sows were added to the kill schedule (a 400-pound sow will yield approximately 190 pounds of sausage). However, as the day progressed, sausage sales moderated and some sows were held back. The owner indicated that slaughter would commonly be adjusted six to twelve times per day to meet product flow and type of product as indicated by direct information from the retail sales. The combination of a holding facility for slaughter equivalent to a typical feeding floor and close direct monitoring of the retail sales case and the slaughter and processing facility allows Nahunta to implement a real-time production response system.

Tight supply control exists for Nahunta's fresh pork products as well. The maximum time any product will be sold as fresh is forty-eight to fifty-six hours from slaughter. All fresh product is sold within thirty-six hours after being removed from the packing plant cooler. Any product not sold is moved to a freezer, discounted an average of 20–50 cents per pound and sold only as frozen. However, on one day of the site visit they moved only 300 pounds of fresh product into the freezer on a weekly sales volume of approximately 75,000 pounds. This tight product flow is due to pricing to move product and the flexibility created by variable slaughter to meet expected daily demand.

The Egg & I Combines Horizontal Market Formats with Vertically Integrated Production

Although The Egg & I is a completely vertically integrated production chain, their experience has shown the need to find multiple outlets to maximize customer exposure and maintain sales volume to fit their production chain. Rather than having one market outlet, their current marketing efforts include three different formats: (a) wholesale sales of product to local small- and medium-sized grocers; (b) sales through area restaurants; and (c) retail direct sales to customers. Direct retail sales include a new on-site retail store, mail order through the Egg & I Newsletter (also available via the Internet) and the Dean & DeLuca catalog, and the operation of a lunch bus that supplies breakfast and lunch at area flea markets and caters to special occasions (weddings, graduations, family reunions).

Wholesale pork sales to grocers selling Egg & I products constitute 36% of the revenues for the Egg & I Farm. However, they account for 45% by volume. The reason is that wholesale pork sales (even though they are fully case-ready products as sold in the ButchersChop) are sold at a $0.50 discount per pound to allow the retailer to make a profit margin. However, this high volume outlet allows Egg & I to support their high-end specialty products of pork chops and hams, which sell for as much as $70 per item (hams in Dean & DeLuca) but on a much lower volume basis during seasonal slumps between Easter and Christmas. The goal is to have the volume move through the on-farm ButchersChop and also capture the additional $0.50 per pound for retail. The convenience of the one-stop grocer, however, is still what commands the volume and supports The Egg & I's ability to market smaller volume specialty items.

Other synergies exist between market outlets. For example, hams sold to restaurants or provided for large barbeque events are custom cut for customers, resulting in potential trim loss. The ham is weighed and priced simply as a trimmed bone-in ham, which is cut to the customer's specification at no extra charge. The trim, which would otherwise be a loss, is sold through the Egg & I's catering sales, enhancing overall value. Similarly, The Egg & I requires restaurants featuring their products to label them as Egg & I products and provide contact information for subsequent direct purchases from The Egg & I ButchersChop.

In summary, each of the cases found synergies within their scope of vertical and horizontal activities to overcome cost deficiencies. It is likely that larger vertically integrated firms will also capture technical and transaction economies from vertical integration. However, the larger firms are most likely to capture those economies arising from hurdles created by their larger-scale operations. As suggested by previous research, those hurdles include search costs for quality and procurement from a large number of producers. The key insight is that the three case firms found ways to differentiate themselves to their customers even in the organization and management of their supply chain activities. Porter refers to this in his classic article on strategy as “forging fit in the supply chain.”

Differentiation through Advertising and Promotion

The final aspect of potential competitiveness is differentiating the products to customers through branded advertising and promotion, as suggested by Brester and Schroeder. The Egg & I Pork Farm provides the broadest array of advertising alternatives. In 1998, the company reported $11,740 in advertising costs. However, this did not include much of the advertising that occurs within each marketing outlet.

One key part of the promotion is the contained in the name of the farm. The Egg & I Pork Farm was derived from the 1945 book written by Betty MacDonald about two city folk who moved to the wilderness and began raising chickens. The original book and copies of a 1950's movie are prominently displayed in the ButchersChop to provide an image and context for customers.

The newsletter provides educational descriptions of the pork operation, often describing how products are made, the care and safety assurance that goes with the products, and other facts about pork production. An online version of the newsletter is available on the Internet at http://www.eggandiporkfarm.com. Photos of the operation are included along with a description of the production protocols and product listings. Recipes and on-line ordering are available. This serves as an additional connection to their customers. Price and product listings are also included in the newsletter along with an order form and map to the farm. Seasonal price specials and other marketing promotions are also prominent.

A key form of “free” advertising has come from extensive featuring of The Egg & I Pork Farm in regional magazine stories. As an example, it has been featured in Saveur, a lifestyle magazine format, Connecticut Magazine, and other national magazines such as Bon Apetit and Wine and Food. Hence, the story has created a presence that gets the brand and name recognition crucial to acquiring new customers.

Finally, the Egg & I brands all of its products offered through other outlets. For example, several area restaurants feature Egg & I pork chops. Those who feature them exclusively can use the Egg & I brand on their menus and in advertisements. This represents a form of co-branding with hopes of contributing to sales through the Egg & I's other outlets.

Conclusion

Although all case participants must address operational issues such as regulatory compliance, labor management and financial management, each proprietor is adamant that the bottom line for success is differentiating their marketing and merchandising strategies from the commodity pork market. These goals are primarily accomplished through a combination of strategies, including managing product price/yield relationships and inventories, coordinating production systems to fit their market demand, accessing the customer in creative ways to improve sales, and developing advertising strategies that help establish them as a brand in the market place.

Consistent with previous research suggesting that pork markets are competitive, all three participants base their pricing on market-observed prices. However, each managed to maximize returns to prices through managing product differentiation and yields. Beyond managing product attributes, all three also illustrated ways to differentiate their supply chains to form a competitive niche. This observation corresponds to Perry's incentive for vertical coordination of finding technical complementarities. Remarkably these small supply chains have managed to find competitive niches despite larger competitors who may capture greater economies of scale.

Although none of the case participants initially set out to include retail sales, each finds it necessary to compete. This arises from the need to directly interact and learn from their customers, to gain a greater share of the final pork dollar, to maintain profitability and to better merchandise final products to match production flow and timing. In all cases, the proprietors recognize that the wholesale pork market is highly competitive and driven largely by cost and throughput, which limits their ability to manage prices. Moving to retail allowed them to execute merchandising strategies and gave them some modest competitive relief from the commodity market. The case participants recognized that they must access the consumer to capture their preferences for differentiated products. Many current value-added pork initiatives focus on packing and processing as the critical component. However, these cases suggest it may be the retail end of the chain. Hence, new initiatives should carefully consider where to focus marketing and production efforts and consider creative ways to gain direct access to the consumer.

The firms' willingness to share their marketing strategies openly was perhaps the most compelling evidence that they believed they had a defensible competitive niche. All three participants explicitly said that it was not a problem because they were confident in their uniqueness and ability to maintain their chosen market position. In fact, Nahunta Pork's founder cites he has provided his full knowledge to at least twenty other start-up enterprises in their own market region. Only one exists today: Nahunta owns the competitive niche.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge and thank the National Pork Producers Council and the National Pork Board for project funding. A complete series of supporting publications is available from the National Pork Board, Des Moines, Iowa. I would also like to thank Jeff Ward, formerly of the National Pork Producers Council, and Dennis DiPietre for assistance in the project. Special thanks also to the case study participants for providing full access to their operations and records. Finally, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and Scott Swinton, Case Study Editor, for their comments that greatly improved this manuscript. Any errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the author. This research was supported by the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station.