The Usefulness of Experimental Auctions in Determining Consumers' Willingness-to-Pay for Quality-Differentiated Products

Abstract

The validity and effectiveness of using experimental auctions to elicit consumers' willingness-to-pay for closely related, quality-differentiated products is examined. The effect of panelists' demographics on bid values and auction winners, and the impact of experimental procedures on auction prices are analyzed. Demographic variables are poor predictors of bids and auction winners. Experimental procedures such as panel size and initial endowment influence market price level. Relative bid differences for paired samples are primarily influenced by relative differences in taste panel ratings. Relative willingness-to-pay values elicited through experimental auctions appear valid, while actual willingness-to-pay values are influenced by experimental design.

In recent years, agricultural economists have become more involved in marketing research. This phenomenon is likely due to the continual evolution from marketing agricultural commodities to individual agricultural products. One area where agricultural economists' skills have been valued is consumer acceptance and willingness-to-pay (WTP) research on new products and different product attributes.

Previous studies conducted by economists have used contingent valuation methods to form hypothetical scenarios to measure WTP. A central question regarding contingent valuation is whether values elicited from hypothetical surveys reflect consumers' true WTP. Due to the concern over the “hypothetical nature” of the contingent valuation approach, research conducted more recently has used experimental economic procedures such as laboratory experimental auctions to elicit WTP for new products and product attributes. A number of different auction techniques exist, but the majority of the research has used a variant of the second-price, sealed-bid auction, frequently referred to as a Vickrey auction (Buhr et al., Hayes et al., Lusk et al., Menkhaus et al., Melton et al., Roosen et al., Umberger et al.). In a Vickrey auction, the winner is the highest bidder, but he or she only pays the second-highest bid price (Vickrey).

Recently, a team of meat scientists and agricultural economists conducted a series of experiments where consumers were recruited to participate in a taste panel comparing three pairs of beef steaks. The steaks differed in specific quality and flavor attributes, but were of similar tenderness. This type of flavor-differentiated, but tenderness-standardized product is not presently available in the marketplace. The meat scientists were interested in determining if consumers could taste flavor differences and if they had a preference. The agricultural economists wanted to determine the consumers' “passion for their preference” through their WTP for their preferred steak flavor. A variant of the Vickrey auction, a fourth-price, sealed-bid auction was used to determine consumers' WTP for each steak and all auctions were binding.1

Consumer panelists participating in the beef study were paid cash prior to participating in the experiment. The cash was used to compensate participants for their time, and also to provide them with a budget to bid on and purchase steaks. During the experiment, the scientists observed that some panelists entered a bid of zero for all auctions and did not want to purchase any steaks, regardless of how they rated them on palatability. Additionally, other panelists submitted bids on all steaks, but their bids were never high enough to “win” an auction and to purchase a steak. Other consumer panelists appeared quite rational, submitting bids that were high enough to “win” preferred steaks, but bidding lower on their nonpreferred steaks and not “winning” them. In several instances, a panelist bid high enough to “win” all six auctions and was required to purchase six steaks, both their preferred and nonpreferred steaks.

How valid are the WTP results elicited from experimental auctions if consumer behavior within the experimental auction is influenced by their demographics or their knowledge of the product in the experiment? Does economic theory hold up in experimental auction markets? Do the experimental auction procedures influence the actual bids, and consequently the WTP results? How reliable are relative bid differences between closely related, but quality-differentiated products?

This paper extends the knowledge and understanding of experimental auctions by evaluating the dynamics of repeated, binding, uniform-price (fourth-price) auctions and the bidding behavior of the panelists. Three specific objectives are: (a) to examine qualitatively and quantitatively the impact of consumer demographics on bidding behavior in an experimental auction; (b) to analyze market demand, or more specifically, market price in an experimental auction when supply is fixed but demand varies; and (c) to evaluate the usefulness of experimental auctions in determining relative WTP values for closely related, but quality-differentiated products.

Experimental Auction Theory

The Vickrey auction and similar, uniform, nth-price auctions, are assumed to be demand revealing because they provide an incentive for auction bidders to reveal their true preferences. According to Vickrey's theory, there is no gain from strategic bidding because the market price is independent of a participant's bid. The market price is defined as the nth price. Participants who bid less than their true value reduce their chances of winning the auctioned good at a potentially profitable price. On the other hand, by submitting a bid more than their true value, auction participants have a greater probability of winning, but paying a price that is in excess of their true value (Shogren et al. 1994b).

The demand-revealing theory of the Vickrey auction is based on the assumed behavior of participants. This theory may fail when applied to a simulated “real-world” laboratory setting where consumers use real money and actually experience the product in question.2 Previous research has suggested a need for several trial auctions for bidders to experience the unique auction concept and to form their true values (Coursey and Smith, Fox et al., Hayes et al., Hoffman et al., Kagel, Menkhaus et al., Shogren et al. 1994a). Shogren, List, and Hayes recently examined auction behavior for goods of varying familiarity.

The previous auction literature has primarily examined the theory of the auction under different experimental conditions and with alternative types of products. This research extends the preceding work by also considering the consumers selected for the experiment.

Experimental Procedures

Twenty-four consumer taste panels were conducted in Chicago, IL and San Francisco, CA to determine consumer WTP for beef flavor. Consumers were recruited over the phone, and those who met the research requirements were invited to participate in a panel where they would have the opportunity to taste New York Strip Steaks. Consumers were told that they would receive $25 in Chicago and $35 in San Francisco for their participation, and that they would have the option to purchase steaks similar in quality to those they sampled in the taste panels. Twelve taste panels consisting of twelve consumers each were scheduled in both locations.

Upon arriving at the research facility, panelists were paid the money they were promised, and were asked to complete two surveys. The first survey contained questions about the participants' demographic characteristics and meat purchasing behavior, and the second survey assessed participants' beef knowledge. The unique fourth-price auction was explained, and three practice, nonbinding auctions were completed to familiarize the participants with the auction process. Panelists were encouraged to bid their true value for each of the steaks they would sample and were reminded that if they “won” a binding auction, they were obligated to purchase the one-pound package of steaks at the auction market price (fourth-highest bid).

The individual experimental auctions consisted of four steps: (a) panelists completed a “blind” taste test and sensory evaluation of a pair of steak samples; (b) panelists submitted two bids in dollars per pound for each steak sample in the pair; (c) all bid sheets were collected by the auction monitors; and (d) the auction monitor announced the market price (fourth-highest price) for each steak sample in the pair. The four-step process was completed three times: twice for steaks differing in marbling level (intramuscular fat content) and once for steaks differing in country-of-origin. Thus, each panelist had the opportunity to bid on and purchase three pairs of steak samples; or in other words, panelists submitted a total of six bids and could have won or have purchased six steak packages. Because the auction was a fourth-price auction, three one-pound packages of frozen steaks were sold for each of the six steak samples. Panelists were only allowed to purchase one package of steaks in each auction, so while the auction was a multiunit auction, it was a single-unit rather than multiunit demand auction.3

To prevent explicit collusion, which the theoretical Vickrey auction model assumed not to exist, communication was not allowed between participants during the auction procedures. All participants knew how many items were for sale in each period (three) and were aware of their competition. The participants knew their own valuation for the product and were informed of the market price, the fourth-highest bid, following each pair of auctions. They were not given the actual bid values of their competitors. Thus, the independent private values information structure assumed in the Vickrey auction was present.

Methods

Tests of Consumer Theory in Experimental Auction Markets

The experimental design of this research was unique compared with previous applied experimental economic studies that measured consumers' WTP for food products. Several characteristics of the auction design allowed examination of the factors influencing both individual demand and market prices in experimental sealed-bid Vickrey auctions. Consumer WTP was measured on an already established familiar market good—beef steaks—that possessed two different quality attributes. Because consumers did not need to learn their preferences for a new product (Shogren, List, and Hayes) the factors influencing consumers' demand for a familiar market good in a theoretically demand-revealing auction could be tested. Specifically, consumer behavior within the experimental auction could be explored, and the influence of participant demographics and their knowledge of the experimental product on individual demand could be examined.

Rather than randomly selecting a binding auction (as suggested by Shogren et al. 1994b), all of the auctions were binding, purchase auctions. Accordingly, economic theory would suggest that as subsequent auctions were run, the market price may decrease as some buyers (panelists) become satiated and either place a lower value on the next good sold or choose to drop-out of the bidding process. This phenomenon is referred to as the “wealth effect” in auction literature (Friedman and Sunder, Shogren et al. 1994a). If the wealth effect existed because of the binding nature of our successive auctions, then the market price in the successive binding auctions could be downward biased and the validity of the WTP value would be questionable.

While the experiment was designed to have twelve panels of twelve participants in each city, not all the recruited panelists arrived at the research sites. Therefore, the panels varied from 6 to 12 participants. This allowed us to examine a change in market demand and the resulting auction market price when the experiment is conducted with a varying number of consumer participants. How responsive is the auction market price to the size of the experimental panel? Two different payment levels and locations also were used in the experiment, which may have affected the market price.

Consumer Behavior in Experimental Auction Markets

Not all taste panelists in the experiment chose to actively participate in the auction. Panelists were told they could submit a bid of zero if they did not want to participate. However, if they submitted a zero bid, they were asked to explain why. This qualitative information is summarized in the results section. The majority of the panelists did submit bids; however, some panelists were not able to win an auction because they never submitted a bid above the market price. Conversely, other panelists won all six binding auctions. This experiment was primarily designed to determine consumers' taste preferences and to elicit consumers' WTP for their preferences. Yet, from the bids it was obvious that some panelists were winning auctions on products they did not prefer, while others did not win an auction on a preferred product. Are there demographic factors that help explain which participants will be auction winners?

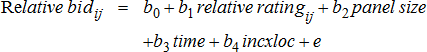

(1)

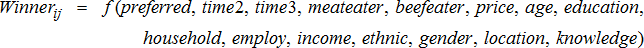

(1)In equation (1), the variable preferred is equal to 1 if steak j was the consumer's preferred steak sample in the pair and was equal to 0 otherwise. Time2 and time3 are dummy variables equal to 1 if steak j was in the second pair or third pair of steaks auctioned, respectively. The other independent variables used in the model were chosen based on previous studies examining consumer beef demand and assumed socioeconomic variables that would likely affect an individual consumer's demand for beef (Capps, Menkhaus et al.). Meateater is a categorical variable representing the number of times per week meat is eaten in the home. Beefeater is a discrete variable equal to 1 if beef is the meat product consumed most often in the household, and is equal to 0 otherwise. Price is also a discrete variable equal to 1 if a participant indicated that price is the most important driver of their shopping decisions, and equal to 0 otherwise. Age, education, household, employ, and income are all categorical variables representing the effect of a participant's age, education, household size, employment status and annual income on the probability they will win or lose an auction. Ethnic is equal to 0 if the participant is Caucasian, and 1 otherwise. Gender is equal to 1 if the participant is female. Location is equal to 1 for Chicago and 2 for San Francisco. Knowledge is the panelist's score on the beef knowledge quiz (10 = perfect score). Each of these categorical variables is further described in table 1.

| Variable | Definition | Possible Values |

|---|---|---|

| Winner | Consumer won or lost an auction | 1 = consumer won at least one auction, |

| 0 = otherwise | ||

| Meateater | Number of times per week meat was eaten in the home | 1 = 1–2 times, 2 = 3–4 times, 3 = 5–6 times, 4 = 7–8 times, 5 = 9–10 times, 6 = more than 10 times |

| Beefeater | Meat product consumed most often | 1 = beef was the meat product consumed most often, 0 = otherwise |

| Price | Driver of shopping decisions | 1 = price, 0 = otherwise |

| Age | Consumer's age category | 1 = under 25 years, 2 = 25–34 years, |

| 3 = 35–44 years, 4 = 45–54 years, | ||

| 5 = 55–64 years, 6 = over 64 years | ||

| Education | Level of education | 1 = completed at least a college degree, |

| 0 = otherwise | ||

| Household | Number of family members living at home | 1 = four or more family members, 0 = otherwise |

| Employ | Category of employment level | 1 = employed either full or parttime, |

| 0 = otherwise | ||

| Income | Income category | 1 = 10,000–19,999, 2 = 20,000–29,999 |

| 3 = 30,000–39,999, 4 = 40,000–49,999 | ||

| 5 = 50,000–59,999, 6 = 60,000–69,999 | ||

| 7 = 70,000–79,999, 8 = 80,000–89,999 | ||

| 9 = 90,000–99,999, | ||

| 10 = greater than 100,000 | ||

| Ethnic | Ethnic background category | 1 = Non-Caucasian, 0 = Caucasian |

| Gender | Gender category | 1 = female, 0 = male |

| Loc | Location of taste panel research | 1 = Chicago, 2 = San Francisco |

| Knowledge | Panelist's knowledge quiz score | 10 = perfect score, 0 = no correct answers |

Market Price and Market Demand in Experimental Auction Markets

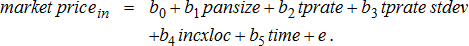

(2)

(2)It was hypothesized that the beta coefficients associated with Pansize, tprate, and incxloc would be significant and positive. As previously mentioned, panel size varied from 6 to 12 panelists while available supply remained at three steak packages. Theory would suggest that the market price should increase with larger panel sizes. All panels were presented with the same steak comparisons. A change in the average taste panel rating can be thought of as a change in consumers' tastes and preferences. A higher rating would indicate the panelist had an increased preference for that sample and should increase the market price. While no a priori knowledge existed on likely differences in demographics between the Chicago and San Francisco consumers, it was hypothesized that the higher income endowment given to the San Francisco consumers would have increased their demand ceteris paribus.

Additionally, it was hypothesized that the beta coefficients for tprate, stdev, and time variables would be significant and negative. Increased variability of the taste and preferences of the panelists, as indicated by the variability of their ratings would be expected to decrease demand and market price. Previous auction literature suggests we may have created a downward bias in successive auctions by having all auctions binding. Thus, we expected demand and market price to be lower for each successive auction.

Relative Bids from Paired Experimental Auctions

Frequently in market research, individuals are less concerned about actual price levels of a new product, and are more interested in the relative price for the new product compared with a close substitute (Menkhaus et al., Hoffman et al.). Thus, the price premium or price discount the product may sell for in the market place compared with a standard or base product is of interest. How effective are experimental auctions in capturing these relative WTP values?

(3)

(3)Results

A total of 248 consumers participated in the taste panels, 124 in both Chicago and San Francisco. The participants were primarily Caucasian females between the ages of thirty-five and fifty-four years with an annual household income of $40,000 to $69,000. The participants also consumed a large amount of meat in their diet; 58% of the respondents indicated they prepared and ate meat three to six times per week. Beef (63%) and chicken (27%) were the meat products preferred by most of the participants.

The Factors Influencing Participants' Bidding Behavior in Experimental Auction Markets

The first objective of this research was to determine the factors influencing participants' bidding behavior in an experimental auction market. To address this objective, a frequency analysis was completed to examine the number of winners and nonwinners in the data set. A panelist was defined as an auction winner if they submitted a bid above the market price in at least one of the six binding auctions and a nonwinner otherwise. Approximately 65% of the participants won at least one auction, 20% of the participants won at least four auctions, and seven individuals (only 3%) won all six auctions.

Of those individuals winning an auction, approximately 46% won at least one sample that was not their preferred sample in the pair. These statistics indicate that some consumers may have consistently bid a slightly higher or lower value (strategically bid) to increase the probability that they either won or lost an auction. Were there any demographic characteristics that increased the probability of a participant winning or losing an auction? Did some participants who indicated they ate beef several times per week place a higher value on the steak than consumers who ate primarily poultry or pork? Did participants in a lower income category participate only for the monetary payoffs and try to avoid winning an auction? An answer of “yes” to any of these questions may indicate that some participants' auction behavior was inconsistent with the demand-revealing property of the Vickrey auction (i.e., some participants did not bid their true value) and the validity of the auction is questioned.

Table 2 provides a somewhat qualitative analysis of the consumers who chose to exit the market altogether and submitted zero bids on all products (twenty-two participants). The quotes from individuals who consistently bid zero in all six of the experimental auctions were placed in five categories: unknown source, storage, not interested in purchasing meat, needed money, and did not like the product. The comments ranged from “not interested in purchasing steak today” to “college student, [and I am] broke.” Some of these reasons may be representative of the same group of people who choose not to purchase beef in the supermarket on certain days, influencing the “real world” market price for beef. This raises the question of whether or not these individuals bias the auction market, and what can future researchers do to prevent these individuals from participating in research trials? Or should anything be done to prevent them from participating because they actually represent true market behavior?

| Category | Comment |

|---|---|

| Unknown source |

|

| Storage |

|

| Not interested in purchasing meat |

|

| Need money |

|

| Did not like |

|

Equation 1 was estimated with the logit procedures of SAS to examine the effect of demographic variables on the probability that an auction participant would be an auction winner. The results of the logit model are shown in table 3. The coefficients on the preferred, beefeater, price, education, and ethnic variables were all significant (∀ = 0.05). The results indicate that consumers participating in the auction were more likely to win a steak that was their preferred sample in a pair; and participants who consumed beef most often in their household were less likely to win an auction. Additionally, consumers with a higher education, those who were price-driven and non-Caucasian consumers were more likely to win an auction. The negative sign of the beefeater coefficient is opposite of the expected sign; this may indicate that the participants in this study who specified on the survey that they did not typically purchase beef do so because of price, not because they prefer another meat product. While a few of the independent variables were significant, overall the model was a poor predictor of auction winners; the Pseudo R2 value was 0.10.

| Winners Logit Model | Bids OLS Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Chi-Square | Coefficient | t-value |

| Intercept | 2.570a | 16.20 | 1.670a | 4.366 |

| Preferred | 1.028a | 69.80 | 1.246a | 16.534 |

| Time2 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.050 | −0.546 |

| Time3 | −0.082 | 0.300 | −0.290 | −3.154 |

| Meat Eater | −0.023 | 0.246 | −0.044 | −1.547 |

| Beef Eater | −0.384a | 7.871 | −0.303a | −3.688 |

| Price | 0.379a | 5.691 | 0.371a | 3.922 |

| Age | 0.053 | 0.597 | 0.037 | 0.881 |

| Education | 0.304a | 10.895 | 0.149a | 4.63 |

| Household | 0.051 | 0.866 | 0.040 | 1.197 |

| Employ | −0.138 | 0.299 | 0.104 | 0.224 |

| Income | −0.025 | 0.901 | 0.016 | 1.000 |

| Ethnic | 0.123a | 3.745 | 0.026 | 0.715 |

| Gender | −0.086 | 0.596 | −0.084 | −0.84 |

| Loc | −0.049 | 0.128 | 0.238 | 0.282 |

| Knowledge | −0.073 | 0.072 | 0.022 | 0.921 |

| Pseudo R2 = 0.104 | R2 = 0.087 | |||

- a Variable is significant at the ∀ = 0.05 level, n = 1,319.

In addition to the logit model in equation (1), several other approaches were used to estimate the relationship between auction winners and demographics. However, none of the other approaches improved the results. The other models were even less accurate at predicting bidding behavior. For example, a model was estimated where the panelist's bid for steak j was the dependent variable; and the independent variables were similar to equation (1). The results of this estimation are also shown in table 3. For the bid model, the R2 value was 0.09 and the independent variables that were significant are comparable to the significant variables that were in the logit model. Thus, demographic variables were poor predictors of auction winners from taste panel experiments, and researchers may not need to be as concerned as previously thought when selecting auction participants that fit some specific profile.

The Factors Influencing Market Demand and Price in Experimental Auction Markets

The second objective of this research was to determine the factors influencing market price and market demand in an experimental auction market. The overall average market prices for all auctions and the average market prices for each of the panel sizes are shown in table 4. In order to examine the factors influencing market demand in the auctions, equation (2) was estimated using the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression procedures of SAS. The results of the estimation are shown in table 5. The independent variables explained 68% of the variation in market price (adjusted R2 = 0.68). The variation in market price in the experimental auctions was explained by the same factors that influence market price or shift market demand in the “real world.”

| Average Market Price for Treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair One | Pair Two | ||||||

| Pair Three | |||||||

| Panel Sizea | No. of Obs.b | High Marbling | Low Marbling | High Marbling | Low Marbling | ||

| Domestic | Foreign | ||||||

| 6 | 3 | $1.75 | $0.92 | $1.31 | $0.67 | $1.02 | $0.37 |

| (1.14) | (0.14) | (0.59) | (0.30) | (0.91) | (0.23) | ||

| 7 | 1 | $2.00 | $2.79 | $2.79 | $2.50 | $2.00 | $0.50 |

| (NA) | (NA) | (NA) | (NA) | (NA) | (NA) | ||

| 9 | 2 | $1.98 | $2.12 | $1.53 | $2.00 | $2.00 | $0.53 |

| (0.39) | (1.23) | (0.67) | (0.01) | (0.71) | (0.67) | ||

| 10 | 3 | $2.99 | $2.56 | $2.95 | $2.85 | $2.85 | $2.73 |

| (0.01) | (0.11) | (0.51) | (0.57) | (0.26) | (0.45) | ||

| 11 | 5 | $3.76 | $3.30 | $3.69 | $3.25 | $3.15 | $2.91 |

| (0.78) | (0.60) | (0.70) | (0.87) | (0.60) | (1.00) | ||

| 12 | 10 | $3.08 | $3.06 | $3.36 | $2.90 | $3.51 | $2.82 |

| (0.31) | (0.69) | (0.52) | (0.69) | (0.82) | (0.64) | ||

| Overall meanc | $2.91 | $2.69 | $2.94 | $2.59 | $2.85 | $2.23 | |

| (0.85) | (0.95) | (0.99) | (1.00) | (1.08) | (1.22) | ||

- a Panel size is equal to the number of participants (consumers) in each panel.

- b Number of observations is equal to the number of panels in a panel size category.

- c Overall mean is the average of all market prices for a treatment (n = 24 per treatment).

| Variable | Coefficient | t-value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −3.2979a | −6.14 |

| Pansize | 0.2812a | 10.66 |

| Tprate | 0.6385a | 6.50 |

| Tprate stdev | −0.1168 | −0.86 |

| IncxLoc | 0.2055a | 1.94 |

| Time | −0.0796 | −1.08 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.68 |

- a Variable is significant at the ∀ = 0.05 level, n = 120.

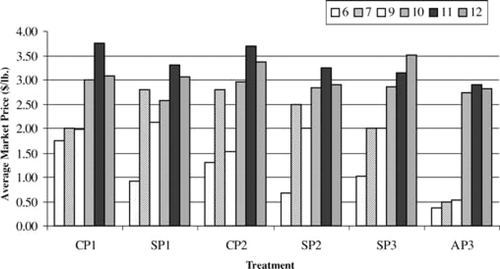

The pansize, tprate, and incxloc coefficients were all significant and as hypothesized the signs on all of three coefficients were positive. As panel size increased, market demand and price increased. The average market prices for various panel sizes are plotted in figure 1. Graphically, the average market price appeared to increase for all treatments as the panel size expanded from six to eleven panelists. The average market price then decreased slightly from panels of eleven to twelve participants.

The significance and positive sign of the tprate coefficient indicates that market prices increased with higher taste panel ratings (greater tastes and preferences increased market price). The significant and positive sign on the incxloc dummy variable was as hypothesized. The San Francisco consumers were given a larger income endowment, which may have increased their demand. An increase in market income should shift the demand curve out and raise market price. Other immeasurable factors may also have influenced this income by location dummy variable. Both tprate stdev and time were negative as hypothesized; however, neither variable was significant. The insignificance of the time variable indicated that consumers in this study did not reach a significant level of satiation; thus, the wealth effect was not significant in our experiment.

Average auction market prices by treatment and panel size

Relative Bids versus Relative Sensory Ratings

Results from the prior section documented that in addition to bids being influenced by sensory ratings, the auction design also had a significant impact on the average bids and price levels in each experimental market. This section documents the impact of the same independent variables on the relative bids of two closely related samples. Equation (3) was estimated using the OLS regression procedure in SAS. The results are displayed in table 6.

| Individual Data | Average Taste Panel Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Err. | Coefficient | Std. Err. |

| Intercept | 0.2874 | 0.3271 | 0.6226 | 0.7969 |

| Relative sensory ranking | 1.2867a | 0.0718 | 1.1508a | 0.3703 |

| Time | 0.1028 | 0.0524 | 0.2345b | 0.1078 |

| Panel size | −0.0498b | 0.0247 | −0.0683 | 0.0439 |

| IncxLoc | −0.1614 | 0.0838 | −0.3144 | 0.1759 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.39 | 0.26 | ||

- n = 578 for individual model and n = 72 for panel average model.

- a Coefficient is significant at the ∀ = .01 level.

- b Coefficient is significant at the ∀ = .05 level.

Relative bids of the paired steaks samples were positively and significantly (α = 0.01) influenced by the relative overall sensory ratings for the samples. Thus, the experimental auctions appear to be capturing WTP differences that are consistent with individual consumers' sensory rating differences. Panel size was significant (α = 0.05) and negative on relative bids. The timing of the auction, first, second, or third pair of auctions, differences in initial endowment paid to the participants and the location of the trial did not significantly impact participants' relative bids.

Equation (3) was also estimated using average relative bids for each panel (table 6). The average panel data results are very similar to the individual data results. The average relative sensory ratings have a positive and significant (α = 0.01) impact on the average relative bids for each panel. The time variable is significant (α = 0.05) and positive. The third pair of steaks in the experiment had the largest sensory rating difference and the largest bid difference. Thus, the time variable is likely positive due to this factor, rather than the timing of the auction pair influencing the relative bids. The other two experimental design variables are nonsignificant. These results substantiate the hypothesis that relative bids in an experimental auction are reflective of relative differences in the quality attributes of the products and are less biased by experimental auction procedures then are the actual bid levels.

Summary

Consumers were recruited to participate in an experiment where they tasted a series of paired beef steak samples with different quality attributes. Consumers provided sensory ratings on the steaks and then participated in fourth-price, sealed-bid, binding experimental auctions. The auctions were used to determine consumers' WTP for their preferred steak flavor. As the experimental auctions were conducted, we observed consumer behavior that led us to examine the effectiveness of using experimental auctions to capture WTP values for quality-differentiated products.

The results of the logit model suggest that socio-demographic variables are poor predictors of auction winners. While a number of consumer panelists chose not to participate and submitted bids of zero in all steak auctions, their explanation for not participating seemed consistent with the reasons consumers may choose not to purchase steak at a retail market on a given day. In this research, consumers who were price-driven shoppers may have realized that they were getting a “good deal” and may have bid high enough to win multiple auctions and purchase multiple steaks. This behavior also appears consistent with consumer behavior when steaks are put on sale in the retail case. However, in general, socio-demographic variables such as income or age did not influence participants' bidding behavior as previously thought.

The market price, as determined by panelists' bids, was found to be a function of panelists' overall preference rating for the sampled steak. The number of participants in a panel, as well as other experimental procedures (initial endowment and location) also impacted the bid price level. Changes in the bid prices of the auctions in the study appear to be a function of the same factors that affect prices in the marketplace. The relative bids of the paired samples were significantly impacted by the relative ratings between the quality-differentiated products. Experimental auction procedures had less impact on the relative bids between samples than on actual bid levels. Consumers appeared to be expressing their true value differences for the sampled products and the experimental auction provided a valuable measure of consumers' WTP for quality differences.

Implications

The results of this research indicate that individual participants pursuing their own self-interest result in unique experimental auction market prices. How closely these auction prices are to real world observable prices depend upon several experimental procedures. If researchers are interested in the experimental auction price being similar to the real world market price for a product, then pretrial experiments need to be conducted to determine the correct panel size and payment for participation. The experimental auction appears to be an excellent method of determining relative WTP values for similar products.

The use of experimental auctions to determine consumer acceptance and WTP for product attributes or new products is increasing. Each research project requires specific alterations to fit the experimental procedures to the research settings. The information gained from this research should aid future researchers in selecting consumers for their experiment, in eliciting more accurate consumer WTP measures through experimental auction markets and in interpreting the experimental results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank without implicating Chris Calkins, Dale Menkhaus, and Karen Killinger-Mann for their assistance in the research process, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.