Psychosocial and emotional management of work experience in palliative care nurses: A qualitative exploration

Abstract

Background

Palliative care, a crucial aspect of healthcare, faces challenges in psychosocial and emotional management among nurses. With an increasing need for palliative services globally, addressing the emotional well-being of nurses becomes pivotal.

Aim

To explore nurses' psychosocial and emotional work experiences in a palliative care department. The focus is on understanding the challenges, identifying coping strategies, and assessing the impact on professional and private life when facing those experiences.

Methods

A phenomenologic-hermeneutical study involving semi-structured interviews was conducted to comprehend the lived experiences of ten nurses working in a hospital's palliative care department in Spain. Hermeneutic analysis was employed to extract patterns and insights from their experiences. The COREQ checklist was used to report this study.

Findings

Palliative care nurses perceived insufficient preparation in emotional management, grappling with complex family interactions and unique work dynamics. They highlighted the significance of self-protection strategies, experience, clinical sessions, and external resources. Limited training in emotional resilience and challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic emerged as organisational barriers. Nurses expressed a desire for enhanced training and resources.

Conclusion

The study uncovered a deficiency in the emotional preparedness of palliative care nurses, impacting their professional and personal lives. Despite positive aspects, the emotional toll necessitates attention and intervention.

Implications for nursing policy

Comprehensive emotional training for palliative care nurses, addressing barriers, providing resources, and acknowledging emotional labour is necessary. Reinstating paused training sessions and considering specific challenges like those posed by the pandemic are vital. Supporting nurses in their professional and private lives is crucial for sustaining quality care in palliative care departments.

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a), 40 million people require palliative care and only 14% of them receive such health care. Palliative care focuses on assisting individuals with severe or terminal illnesses to provide the best possible end-of-life quality for both patients and their families. Palliative healthcare professionals aim to prevent and alleviate suffering by identifying, assessing, and treating pain and symptoms of patients associated with a terminal illness, whether in the physical, psychosocial, or spiritual realm (ACS, 2023; WHO, 2020a).

Palliative care is central to the WHO's definition of universal health coverage (UHC) as well as the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 3.8 (ICN, 2017), playing a pivotal role in the Nursing Now-driven report (2021) by underscoring nursing's leadership in various areas, including SDGs, UHCs, specialist care services, and policies promoting increased nurse autonomy and involvement in decision-making processes.

The release of the WHO's State of the World's Nursing Report (2020b) marked the first-ever global survey of nursing, revealing an international deficit of at least 6 million nurses and highlighting an urgent need for action to bolster and cultivate the nursing profession. Addressing these shortages is crucial to achieving UHC and universal access to palliative care by 2030 (WHO, 2020). If this critical status in current and future international health policy agendas were not enough, nursing is considered the most honest and ethical profession in the United States, and this position has been maintained for 18 consecutive years, according to Gallup's annual honesty and ethics survey (2023). Thus, nursing professionals within the palliative care context represent a valuable asset for the care provided by the healthcare professionals on the team (Beng et al., 2021; Schroeder & Lorenz, 2018). However, health policies in Spain have led it to become one of the seven countries in Europe that have experienced a trend towards decreasing the total number of specialised palliative care services per population, as Arias-Casais et al. (2020) noted. This is quite notable and directly clashes with the theoretical regional management in the Spanish territory, which refers to adequate palliative care strategies or elements in their policy guidelines (Pivodic et al., 2021).

Nursing in palliative care requires the implementation of skills such as critical thinking, effective communication, compassion, and vulnerability, which will be subject to complex situations involving concepts such as death or grief (Schroeder & Lorenz, 2018). Therefore, compassion fatigue or burnout syndrome represents a prevalent stress in palliative care nurses that compromises healthcare (Cross, 2019; Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2020; Rizo-Baeza et al., 2018). This phenomenon arises due to compassion and empathy experienced after repeated professional exposure to stressful factors and emotionally challenging situations (Cross, 2019). Emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and low personal accomplishment are some characteristics in nurses reflecting this state of emotional stress (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2020; Rizo-Baeza et al., 2018). Additionally, the presence of family members in the care environment can sometimes be an additional stressful factor, as the complexity of the situation may give rise to doubts, changes in expectations, frustrations, or insecurities that need to be addressed by the healthcare team (da Cruz Matos & da Silva Borges, 2018).

Considering ineffective health policies, the emotional vulnerability and psychosocial exposure of palliative care nurses to challenging situations in managing complex patients and family contexts, this study aimed to explore the psychosocial and emotional management of work experience in nurses from a hospital-based palliative care department in Spain. At the same time, we explored specific facets that contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the main aim, not separately but rather in aspects analysed within the context of the primary aim. These specific facets aimed to understand as well the context surrounding nurses in a palliative care department, discover the perceived barriers in the workplace for the development of emotional self-management skills, identify potential facilitating tools in the workplace for the development of emotional self-management skills, understand nurses' self-perception regarding their psychosocial and emotional skills, and explore the effect of work experience on the private lives of nurses in a palliative care department.

METHODS

Design

The current study was conducted using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, as the study's purpose was to explore the psycho-emotional management of work experiences among nurses in a hospital's palliative care department. Heidegger's hermeneutic phenomenology (1923/2005) aims to reveal human existence's more profound meaning or essence by interpreting our lived experiences. Thus, this study delved into nurses' experiences through their ‘narratives’; hence, rather than providing a theory for generalisation, predicting phenomena, or achieving population representativeness, we sought to comprehend the lived experiences of nurses working in a palliative care department (Dreyfus, 1991).

This qualitative investigation adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Tong et al., 2007), available as Supplementary File S1.

Setting and sample

This study was conducted in a hospital-based palliative care department located in Spain. The recruitment process involved purposive sampling guided by inclusion criteria that comprised nursing staff with an active employment contract in the palliative care department at the time of the study and nurses with work experience in the palliative care department exceeding two months. Requiring participants with at least two months of palliative care experience ensures meaningful insights, as this timeframe allows nurses to grasp the challenges. It also aligns with existing literature supporting this study's rationale.

The research team stated exclusion criteria for suffering from any mental illness, cognitive impairment, or psychological disorder.

Data collection

The recruitment process occurred within the same palliative care department, with the collaboration of the supervising nurse. The supervising nurse identified potential participants and encouraged them to contact the principal researcher (EF-V). The supervising nurse's involvement in recommending participants for our study was crucial. Their established relationships within the department fostered trust and ensured credibility, potentially increasing participation rates among fellow nurses in palliative care. Additionally, the supervising nurse's expertise streamlined the recruitment process, expediting participant identification and engagement, thereby reducing burdens and minimising disruptions to patient care. Their adept communication strategies also ensured cultural appropriateness and respected participants' perspectives from the outset, contributing significantly to the success of our study's recruitment efforts.

Data were collected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews with the participants in April 2023. These interviews began with open-ended questions to establish context and gradually evolved, becoming more structured and guided by the course of the nurses' responses through more concise questions. EF-V completed all the interviews and audio-recording, enabling the transcription of conversations and subsequent data analysis.

EF-V wrote a hermeneutic diary as a reflective field notebook to enhance the participants' statements. Additionally, it proved helpful for engaging in a critical introspection exercise and reflexivity (Pilbeam et al., 2022).

The interview guide consolidated the initial categories closely aligned with the main themes. It aimed to understand the context surrounding nurses in a palliative care department, discover perceived barriers in the workplace for the development of emotional self-management skills, identify potential facilitating resources in the workplace for the development of emotional self-management skills, understand nurses' self-perception regarding their psycho-emotional training for managing their work experience, and explore the impact of work experience on the private lives of nurses in a palliative care department. The interview guide is attached as Supplementary File S2. To develop our interview guide, the research team first identified key themes, concepts, and knowledge gaps by conducting a literature review on the research topic (Kallio et al., 2016). This review of previous studies provided valuable insights into formulating targeted questions, thus ensuring our interview questions' relevance and sensitivity by considering them. Finally, to ensure the interview's reliability and robustness, an independent psycho-oncologist from the multidisciplinary team of the palliative care department was consulted to complete a tailored approach to the study's objectives.

Data analysis

For the qualitative data analysis, the research team followed Crist and Tanner's hermeneutic considerations (Crist & Tanner, 2003). The interpretive analysis embraced the research team's expertise, acknowledging subjectivity within the analytical framework.

Researchers discussed the first transcriptions in the initial focus phase to refine the interpretative direction. The team remained open to new research questions or nuances that emerged as interviews unfolded, aligning with the qualitative foundation as a reference (Benner et al., 2009). These initial interpretations guided subsequent interviews to achieve a more nuanced and in-depth understanding of the studied phenomenon.

Regarding the second phase of thematic screening, EF-V extracted central study themes from the participants' statements about their work in the palliative care department. Following this, the research team convened to compare the experiences within the palliative care department that influenced the interviewees and the events categorised within the study themes (Benner et al., 2009). These themes emerged through establishing relationships between the nurses' experiences, resembling a dialogue among narratives clarified through thematic-inductive hierarchisation. Afterwards, minor and major themes were identified based on the qualitative level of abstraction in meaning. The final patterns encapsulated the overarching phenomena within the data; they represented a higher-order structure encompassing major and minor themes, providing a synthesised understanding of the underlying meanings and connections within the interpretative findings. Additionally, EF-V paid close attention to the emergence of paradigmatic or exemplary cases (Benner et al., 2009). These cases referred to interviewees narrating exceptional and profound experiences, to which the research team tended to return to evaluate results from different perspectives. Exemplary cases were visual and significant notations characterising common themes among nurses.

In the third phase of shared meanings, EF-V refined qualitative study patterns through interpretative thematic summaries, constituting the maximum degree of significance (Crist & Tanner, 2003). Again, the research team gathered to assess the focal point and justify the final analysis.

In the last phase of final interpretations and dissemination, researchers, through interpretative thematic summaries and with the aid of the hermeneutic diary, engaged in constant dialogue with the transcribed narratives of the interviewed nurses, shaping the results' writing. This writing drew from notes taken during interviews, transcriptions, and contributions from the research team during meetings. Thus, this facilitated critical review and shared decision-making among the research team, clarifying all issues arising in the current investigation (Crist & Tanner, 2003).

Rigour and trustworthiness

The rigour of the current study was upheld through the criteria suggested by Lincoln and Guba (1985). For a detailed explanation by the research team, the techniques for rigour were also identified to address each criterion in Supplementary File S3.

Simultaneously, we recognised the significance of a meticulous language translation procedure in faithfully conveying the intended meanings of participants across different languages, thereby ensuring the reliability of qualitative research (Yunus et al., 2022). The interviews were conducted in Spanish, the original and native language of the participants. Consequently, the translation process commenced during the dissemination phase of our work in English (Santos et al., 2015). Throughout this phase, we embraced the role of the researcher–translator (Gawlewicz, 2020). In this capacity, the supervising researcher (MA-P), being a native Spanish speaker, undertook the translation of the participants' findings based on notes from the hermeneutical diary.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Research Committee of the Province of Córdoba ethically approved this study (minutes No. 345).

All participants provided written consent before the interview and after receiving a comprehensive overview of the study's objectives, possible risks, and the right to withdraw from the study at any point without affecting their current employment. Privacy and confidentiality were emphasised, with access to raw data restricted to the study team members engaged in data analysis. Furthermore, private rooms were utilised for interview sessions.

Regarding the custody of personal data, the research and data collection team responsible for this work ensured the security and confidentiality of the information they accessed at all times by maintaining confidentiality regarding any information accessed and respecting all aspects related to the custody and access of all types of documentation, adopting security measures to prevent loss or theft.

FINDINGS

Ten Spanish nurses, with an average age of 50, were interviewed. The demographic factors available in Table 1 are pivotal for contextualising nurses' experiences, psychosocial well-being, and work–life balance. For instance, civil status, number of cohabitants, and dependents offer insights into the support systems available to nurses beyond their work environment, potentially affecting their ability to manage emotions effectively. Similarly, details regarding commuting and residence can provide valuable information about the daily stressors and challenges nurses face, which can affect their overall well-being and job performance. Therefore, we contend that these demographic variables are warranted as they contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the various factors shaping nurses' experiences in a palliative care department.

| Participant | Age | Gender | Civil status | Work experience in the palliative care unit (in years) | No. of cohabitants at home (type) | Dependents (type) | Method of commuting to the workplace (commuting time) | Residence in the same area as the workplace | Leisure activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 1 | 46 | Female | Married | 5 | 2 (husband, daughter) | Yes (daughter) | On foot | Yes | No |

| No. 2 | 41 | Female | Divorced | 5 | 1 (son) | Yes (son) | Own vehicle (15 min) | Yes | Yes (sport, travelling, reading) |

| No. 3 | 56 | Male | Married | 4 | 1 (wife) | No dependent | Own vehicle (20 min) | Yes | Yes |

| No. 4 | 56 | Female | Married | 2 | 3 (husband, son, mother) | Yes (son, mother) | Own vehicle (10 min) | Yes | No |

| No. 5 | 54 | Female | Single | 4 | No cohabitant | No dependent | Own vehicle (10 min) | Yes | Yes (reading, walking) |

| No. 6 | 60 | Female | Single | 5 | 1 (mother) | Yes (mother) | Own vehicle (30 min) | No | Yes (travelling, cinema, theatre) |

| No. 7 | 50 | Female | Married | 5 | 4 (husband, son, parents) | Yes (son, parents) | Own vehicle (35 min) | No | No |

| No. 8 | 50 | Female | Married | 7 | 4 (children, husband) | Yes (children) | Own vehicle (1 hour and 15 min) | No | No |

| No. 9 | 52 | Female | Married | 6 | 4 (housemates) | No dependent | Own vehicle (20 min) | Yes | Yes (walking, family and friends gatherings, reading) |

| No. 10 | 42 | Female | Divorced | 1 | 3 (children, partner) | Yes (children) | Own vehicle (15 min) | Yes | Yes (gym) |

There were no dropouts or loss of participants throughout the study. Three overarching study patterns defined the results: a complex, dynamic, and specialised unit; a triangular power relationship ‘barrier–facilitator–self-perception’; and the consequences of psychosocial and emotional burnout.

Narrative development of the findings

This study revealed that palliative care nurses lacked psychosocial and emotional management skills. First, after meticulously describing this service from the perspective of the nurses working there, they considered that working in this service involved a constant emotional burden that was complex to assimilate. However, it also allowed them to face life and death from a more natural and positive perspective. After providing context to the reader, the possible triangular power relationship was explored among the barriers and limitations nurses encountered in their work, the facilitating tools they had to overcome these obstacles, and the consequent self-perception of their caregiving role. This triangular power relationship led to emotional imbalance, as despite having facilitators to combat the barriers and limitations in their work, nurses had a negative self-perception in various areas (emotional management, training, or psychosocial skills). All this manifested in the psychosocial and emotional burnout reported by palliative care nurses.

All elements expressed in the interviews were structured into minor themes and further grouped into major themes to achieve a higher level of qualitative significance. Due to the high complexity and extensive nature of the findings, we have selected the most representative interview excerpts below to support the hermeneutic analysis. All 8 major themes, 25 minor themes, and 315 verbatims synthesising study patterns are available in Supplementary File S4.

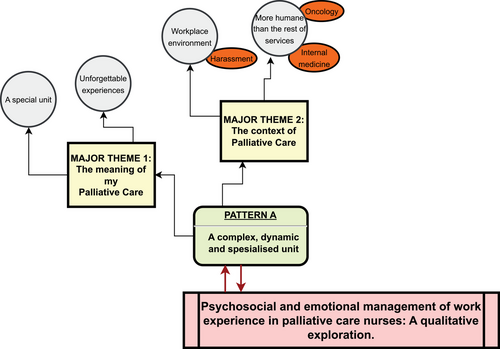

Pattern A: A complex, dynamic, and specialised unit

This first pattern represented the complexity of working in the palliative care department (Figure 1). It contextualised the care provided and delved into the nurses' perception of their work: the meaning they attributed to their care and their feelings when performing their duties in this setting. Furthermore, glimpses were provided regarding aspects that added a certain uniqueness to this department, emphasising the importance of having a positive work environment and highlighting nuances that set it apart from other units.

Major theme 1: The meaning of my palliative care

At least we understood it as a way to relieve families, those families at home who didn't know if they were doing things right or wrong… it was like a way to unburden that family, that's how I understood it initially. (Participant No. 7)

On one hand, you feel good helping people in that situation, but on the other hand, these are things that impact you, leave a bit of a bitter taste, seeing how many difficulties some people can have in life, and how fortunate we are who, for the moment, haven't had to experience any of that, right?. (Participant No. 3)

Major theme 2: The context of palliative care

What can't happen is that you give information, and then another person comes and drops something different. So if you're pleasing this person, and then someone else comes and does the opposite, then what the patient and the family perceive is not the same. (Participant No. 7)

Here, difficult situations have arisen… not long ago, a colleague left, requested a transfer due to a problem of personal rivalry between colleagues, and it was an unpleasant situation for everyone, for everyone. Because that person felt harassed, she was being harassed… by a colleague, and well… imagine what it must be like to come to work, and three people ignore you. [Brief silence] …. (Participant No. 9)

Before, in oncology, it was about hiding. Not talking, the pact of silence, so you entered the rooms and then you were an accomplice in creating expectations for patients that often weren't true. (Silence). (Participant No. 6)

Pattern B: A triangular power relationship ‘barrier–facilitator–self-perception’

This pattern encompassed three interconnected concepts (Figure 2): (1) Barriers and limitations: The various difficulties (both personal and communicative, as well as organisational) that the participants encountered in their caregiving role; (2) Facilitating tools: Strategies derived from professional and personal experience or even external resources that enabled nurses to enhance the care they provided; (3) Self-perception: Perception of the psychosocial and emotional skills used by the interviewees in their daily work.

These three concepts formed the vertices of a triangular power association. Barriers significantly conditioned the nurses' performance in the department, while facilitating tools acted as a counterbalance, allowing them to address the various difficulties encountered in their work and, thus, attempting to rebalance the scales. Consequently, these two aspects influenced nurses' self-perception regarding their work. Therefore, depending on which side of the scale was more inclined (with barriers outweighing facilitators, or vice versa), the nurses' self-perception of the caregiving work was more positive or negative.

Major theme 3: Personal and communication barriers and limitations

What I find most challenging is the denials, trying to help them [the family] and they deny it, deny that help, it's a failure. Because in a way, in palliative care, that's what it's about, and if you're not achieving it in a way, it's a failure. So, it's very frustrating. (Participant No. 8)

… The nurse or healthcare professional is supposed to be there to save lives, but to help them die well, so to speak… well, maybe that would be shocking to them and inconsistent. (Participant No. 7)

Society doesn't talk about death. Society doesn't want to see illness, doesn't want to see death, and here you confront it head-on every day …. (Participant No. 6)

When they [the hospital policy] assign us patients from oncology, you know? You can't give them the time you want for palliative care patients. When they assign us peripheral patients, let's not specify whether they're from oncology, internal medicine, or anything. You can't dedicate the time those patients need. (Participant No. 10)

… We dislike nothing more than when they say, ‘Well, you're already used to it.’ No, we're not used to it! What we've learned now after these years is to manage these situations, but we'll never get used to them …. (Participant No. 2)

Major theme 4: Organisational barriers and limitations

Well, we were going to have meetings; we talked about it with the psychologist; they were going to be on Fridays. But that fell through, before the pandemic, it all fell through, and lately, I don't know where that stands because, of course, they [the psychologists] have a lot of work and many places to go, and, of course, they can't either…. (Participant No. 7)

We often need a bit more dedication to help us handle these situations because, at least for me, I face them as best as I can, you know?. (Participant No. 6)

If there are sick leaves, if there are absences for any reason or due to vacations… I think we are less substituted than in other units. And that sometimes means you can't attend to patients as you would like. (Participant No. 3)

Major theme 5: Facilitating tools: professional experience, personal support, and external resources

I also remember a comment with which I identified a lot about a year and a half ago from a colleague who was retiring and saying goodbye to a colleague … And she said that these are the years in which she has felt more like a nurse than ever. [Brief silence] And I share that same feeling. Being in palliative care makes me feel very much like a nurse …. (Participant No. 3)

Always try to see things from a professional standpoint, try to create a shield, right? And not let it affect you, but there are situations, moments when you are more sensitive, more tired… and patients spend a lot of time here too… and it's tough, it's complicated not to enter that space beyond professionalism. (Participant No. 9)

I really like listening to the psychology of other people who work here because what you see, maybe they see it differently. Well, maybe not, for sure, they see it in a different way. (Participant No. 7)

Well, what helps me is… therapy. [Brief silence]. At first, I tried to do it on my own, sought advice, consulted with the professional psychologists also present in the department, but I really thought that this should be a personal job, right? Something more personal, of oneself, right? And although it's true that we are a team and we help each other, but many times you need a script, a path, something that guides you… [brief pause]. So, I go to therapy, and it's helping me, helping me a lot, to be the professional I want to continue being. (Participant No. 2)

Being there for them. Supporting them, because you know they's going to have tough times, so being there. Knowing that they can tell you things, not feeling awkward, because we were lucky that the whole department went through it at the same time. (Participant No. 2)

Major theme 6: Self-perception of psychosocial and emotional skills

Not everything comes from training; it's also a bit about the experience in the profession. [Brief silence] Gradually, I say, dealing with it is like dealing with the public, right? So, little by little, over time, you see other colleagues, you see the experience that is happening to you, and you learn a bit. (Participant No. 6)

Perhaps I think I should have more ease in certain topics. That there might be silences that could be filled because I don't exactly know how to respond to ensure a person is completely satisfied. You can respond to get through the moment, right? And then you move on. But to ensure that person truly understands you and is satisfied with what they ask, without rambling and going off on a tangent. (Participant No. 7)

… maybe a bit in what I was telling you, reinforcing ourselves a bit in terms of medication management and in the resources available, although that depends on social assistance, but yes, in managing the situation with the resources available for patients and families. (Participant No. 9)

If there were more sessions like the ones we had at the beginning from time to time, with the entire team… well, it wouldn't be bad. Not so much to keep learning, but to continue reinforcing. (Participant No. 9)

Perhaps having something similar to the written nursing rapports, well, in the patient's progress or in some kind of record, I think, in my opinion, if the psychologists follow some type of intervention with the family and the doctor or the team agrees, as in the clinical session, ‘we're going to do this,’ if there is any change in management or anything, well, also having access. (Participant No. 8)

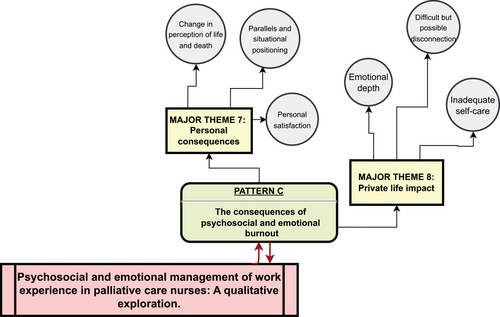

Pattern C: The consequences of psychosocial and emotional burnout

Given all the above, it could be stated that the balance between barriers and limitations and facilitating tools was unbalanced, reflecting a negative self-perception on the part of palliative care nurses (Figure 3). This negative self-perception projected psychosocial and emotional strain, which was interesting to explore. On the one hand, these experiences had consequences that directly affected the care provided by these participants. On the other hand, due to insufficient emotional management, there was an impact not only at a professional level but also in their private lives.

Major theme 7: Personal consequences

Perhaps… on a personal level, I believe that death is a part of life and that sooner or later, it will come to us all. So, for example, I am not afraid of death. I might be afraid of leaving unresolved issues, of the suffering my family might endure due to my absence, but it's not something that currently distresses me. (Participant No. 3)

For example, with my age, when you see someone leaving at the age of my son, well… it hits you… [cries]. You try to cope with it and all, but… it takes a while, it takes a little while to shake it off [awkward laughter]. (Participant No. 4)

Major theme 8: Private life impact

At times, a thank-you from someone in particular, you remember it at home and say, ‘Look what this person told me, look at this.’ So, there are moments, both good and bad, that when you get home, you turn them over in your mind. (Participant No. 3)

You come home stressed, I take it out on food, as I say [laughs]. It's like you have to arrive and do something else. If you finish the evening shift at night, you can't just go to bed; you have to spend some time relaxing, watching TV, or whatever, to distract yourself a bit, and that's it. (Participant No. 1)

Of course, now, I'm a bit different in that aspect. [Brief silence] Yes, because now, when I realize it, I am able to disconnect. Before, I wasn't able to, and I didn't realize it, you know? (Participant No. 2)

Do a lot of things and tire yourself physically. When I say a lot of things, I mean, as I have people in my care, I'm with this one, with the other, with this… I manage two households as well, so… It's not self-care, it's more like overworking myself…. (Participant No. 7)

DISCUSSION

Our study elucidates the intricate nature of palliative care, wherein nurses navigate multifaceted challenges while striving to provide holistic support. This aspect of our study's finding aligns with international research emphasising the complexities inherent in palliative care settings (Clayton & Marczak, 2023; Gagnon, 2020; Maffoni et al., 2020). However, our study offers novel insights into the profound emotional impact experienced by nurses, as evidenced by their reflections on farewells, unique connections with patients, and witnessing poignant moments.

The significance of a supportive work environment in palliative care is well-documented (Collingridge Moore et al., 2020). Our findings reaffirm this notion, highlighting the pivotal role of team cohesion and effective communication in enhancing patient care. Notably, our study unveils the detrimental effects of organisational and policy barriers, such as staff shortages and inadequate training opportunities, which resonate with global concerns in healthcare systems (Froggatt et al., 2019). This underscores the need for targeted interventions to address systemic working challenges palliative care nurses face worldwide.

Palliative care nurses employ various coping strategies to navigate the emotional demands of their roles, as seen in our study and corroborated by Arantzamendi et al. (2024). Notably, our findings shed light on the interplay between personal and professional factors in shaping nurses' self-perception and emotional resilience. This nuanced understanding offers valuable insights for interventions to promote nurses' well-being and prevent burnout, which is increasingly recognised as a global concern in healthcare (Hunsaker et al., 2019). Additionally, in this study, there was a recognition of the need to seek shields to avoid excessive emotional involvement at work. Parola et al. (2018) noted that nurses attempted emotional distancing as a method of self-protection. However, it often proved ineffective and led to feelings of helplessness and distress, becoming harsh to be insensitive, contrasting with Temelli and Cerit (2021).

In general, nurses in both this study and the referenced ones felt unprepared to face certain situations that frequently occurred during their workday (Barrué & Sánchez-Gómez, 2021; Dijxhoorn et al., 2023). They observed deficiencies in managing agonising situations or emotionally processing experiences, expressing the need for pre- and postgraduate training and continuous education, in line with various studies (Barrué & Sánchez-Gómez, 2021; De Brasi et al., 2021; Harrington et al., 2019).

The spillover effect of work-related stress on nurses' personal lives is a recurring theme in our study, resonating with international research on the broader impact of caregiving professions (Fisher et al., 2022). However, our findings underscore the need for targeted support measures to mitigate the negative repercussions on nurses' well-being and interpersonal relationships. This highlights an area where interventions tailored to the unique challenges of palliative care nursing can make a significant difference.

Limitations

The relatively small sample size may appear limiting. Nevertheless, Malterud et al. (2016) state that in qualitative research, a sample rich in information comes from a few participants who confer it. Recall bias is another potential limitation, as participants may not accurately remember or articulate certain aspects of their experiences. Furthermore, the study predominantly focuses on nurses' perspectives, and incorporating the views of other healthcare professionals, patients, and their families could provide a more comprehensive understanding of palliative care dynamics. In reflecting on our research process, we considered our biases, perspectives, and experiences that may have influenced data collection and interpretation. Despite these limitations, our study offers valuable qualitative insights, providing a foundation for further research and potential improvements in nursing policies and practices within palliative care settings. We claim to have encountered redundancy in the data throughout our hermeneutic-phenomenological analysis, where specific themes or patterns reappear consistently across interviews as well.

CONCLUSION

This study provides valuable insights into palliative care nurses' psychosocial and emotional experiences, highlighting the complexities inherent in their roles and the impact on professional practice and personal well-being. Our findings underscored the importance of fostering supportive work environments, enhancing communication, and equipping nurses with essential skills to navigate the challenges of palliative care effectively. By prioritising staff well-being and promoting resilience and self-care, healthcare institutions can create an environment that empowers nurses to deliver high-quality care while safeguarding their well-being. Further research is needed to explore additional factors influencing nurses' experiences in palliative care settings and the efficacy of interventions to mitigate psychosocial and emotional strain.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING POLICY

Our study offers actionable insights for enhancing support policy programmes and promoting resilience among palliative care nurses. These programmes could include regular debriefing sessions, access to counselling services, and opportunities for self-care activities such as mindfulness training and resilience-building workshops. Additionally, institutions should foster a culture of support and appreciation for the invaluable contributions of palliative care nurses, recognising the emotional toll of their work and providing adequate resources to mitigate burnout. To optimise the quality of care offered in palliative care settings, healthcare institutions should address systemic barriers that hinder nurses' ability to deliver optimal care. This entails adequate staffing levels to ensure manageable workloads and opportunities for ongoing training and professional development. Moreover, institutions should streamline communication channels, promote interdisciplinary collaboration to enhance teamwork and care coordination, and invest in ongoing training and education programmes focused on emotional intelligence, communication skills, and self-care strategies. Finally, promoting resilience and self-care is paramount to sustaining the well-being of palliative care nurses. Institutions should boost access to resources such as employee assistance programmes, peer support groups, and counselling services to support nurses in managing their emotional well-being.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: Pablo Martínez-Angulo. Data collection: Victoria Espejo-Fernández. Data analysis: Victoria Espejo-Fernández. Study supervision: Pablo Martínez-Angulo. Manuscript writing: Victoria Espejo-Fernández and Pablo Martínez-Angulo. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: Pablo Martínez-Angulo. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Córdoba/CBUA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.