Understanding of and attitudes towards nursing education reform at medical colleges in Kyrgyzstan: A mixed-method study

Abstract

Aim

To determine teachers’ understanding of and attitudes towards nursing education reform at four medical colleges in Kyrgyzstan.

Background

The quality of nursing education at undergraduate and postgraduate levels has a major impact on patient outcomes and the development of nursing as a profession and a science.

Introduction

Lower middle-income countries have sought to advance their nursing education by adopting the experiences of high-income countries.

Methods

A mixed-method cross-sectional study design was used. The STROBE combined checklist was followed. A cohort of all faculty members at four colleges were included (N = 150). The questionnaire consisted of 10 groups of questions and statements. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected.

Findings

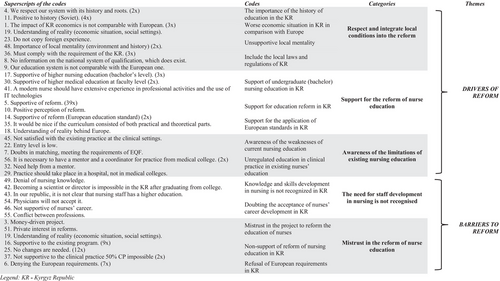

A total of 56.4% of respondents were familiar with the European approach to nurse education; 73.3% of respondents with a nursing education reported being familiar with the European approach, compared to 40.7% of respondents with a medical education. Qualitative written comments yielded 57 superscripts of codes, 14 subcategories, 5 categories and 2 themes as drivers and barriers of reform.

Discussion

The survey revealed weak support for the nursing education reform. Respondents do not envisage nurse education being offered at all three levels of higher education (bachelor's, master's, and PhD), and even fewer recognise nurses as leaders of healthcare institutions.

Implication for nursing

Teachers in nursing programmes should mostly be nurses with academic careers.

Implication for health policy

Nursing is still not recognised as an extremely important health profession that needs to be developed. This misunderstanding and negative attitude towards the role of nurses in the health care system are evident in both the quantitative and qualitative parts of the study.

INTRODUCTION

For years, lower-middle-income countries (LMIC) have sought to promote and strengthen their nursing education by adopting the experiences of high-income countries (HIC) with appropriate and successful education systems. There is a need to regularly and dynamically adapt nursing education to ongoing economic, political and social changes to improve the quality of nursing education and prepare nurses not only for the complexities of the modern healthcare system but also for the health needs of the country (Farsi et al., 2022; Fawaz et al., 2018).

Background

The quality of nursing education and its development at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels have a major impact on patient outcomes and the development of nursing as a profession and a science. Nurses are seen as key facilitators in professional practice, acting as a link between patients and their healthcare providers (Burford et al., 2020). In recent years, a wealth of high-quality research has confirmed the importance of the quality of nursing education and the levels of nurse training. The research underscores the importance of an appropriate number of nurses and their workload, as well as their education. The conclusions of this research call for raising the level of education to a bachelor's degree, (Aiken et al., 2014; Griffiths et al., 2019; Lasater et al., 2021; Porat-Dahlebruch et al., 2022). In addition, the importance of a four-year bachelor's degree in nursing compared to a three-year degree is highlighted as health outcomes were better for nurses with a four-year bachelor's degree compared to those with a three-year degree (Aiken et al., 2014; Christiansen et al., 2018; Haskins & Pierson, 2016; Porat-Dahlebruch et al., 2022).

Global nursing education guidelines have been initiated at undergraduate and graduate programmes primarily in Europe and North America (Wong et al., 2015). Increasingly, there have been calls for the minimum education of nurses to be standardised at the undergraduate level (Cho et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2019). The Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery 2021–2025 (2021) recommend that education programmes be competency-based, use effective learning design, meet quality standards and address population health needs. The document also recommends that LMICs develop “bridge” programmes and other mechanisms to improve students’ educational credentials and demonstrate how advanced education can be accompanied by greater workplace responsibilities and adequate compensation.

Therefore, curriculum reforms are very important for LIMCs. They need to keep up with developments in the field of education around the world and adapt or organise courses to ensure the quality of their curricula. The process of building nursing knowledge evolved from performing basic delegated tasks to critical, scientific and systematised human care, and nursing schools played an essential role in this process by guiding the practice of thinking and caring (Petry et al., 2021; Waldow, 2015). Last but not least, curricular changes need to be part of political movements emanating from representative bodies, new education and health policies, teaching institutions, professors and students (Petry et al., 2021).

Description of nursing education in Kyrgyzstan

The healthcare system in Kyrgyzstan is based on the Soviet system, which included centralised planning and hierarchical administration. Health care is provided through various primary, secondary and tertiary care services (Somani & Karmaliani, 2017). There are 15 public and 12 private medical colleges in Kyrgyzstan. Medical colleges offer a three-year vocational diploma programme for nurses. A five-year specialised higher degree programme in nursing is also offered at the Kyrgyz State Medical Academy with a maximum of 20 students enrolled per academic year. There are no postgraduate nursing programmes per se in Kyrgyzstan; however, some continuous education is available through the Kyrgyz State Medical Institution for retraining and there is continuous education offered to medical, nursing and pharmaceutical workers and other healthcare professionals. Employees in nursing programmes do not hold a bachelor's degree because it was not possible to obtain one previously—the first enrolment of five students started in 2023. A nursing registration system does not exist at the moment, but the Kyrgyz healthcare system is moving towards the registration of health workers via e-health records and developing an independent system of competency assessment.

Somani and Karmaliani (2017) published a situation analysis from the Bishkek region, the country's capital. Most nurses there have a three-year diploma in nursing at the vocational college level. In the European context, this is the equivalent of an in-service degree (European Qualification Framework (EQF) levels 4–5) in nursing rather than an undergraduate degree at higher education colleges and universities (EQF level 6). The author described that nursing education is inadequate, lacks clinical training and is mainly led by physicians. Nurses face challenges such as a lack of staff and medical equipment, exclusion from patient care, planning and documentation, and low salaries. The World Bank reported 5.6 nurses and midwives per 1,000 population in Kyrgyzstan (World health statistics, 2023), whereas the average for EU27 countries was 8.3 nurses per 1,000 population in 2021, including general and specialist nurses and in some countries also associate nurses who have a lower level of qualification (OECD/European Union, 2022). According to the definition of how a general care nurse should be educated in Europe, the current system of education in Kyrgyzstan at the college level can be classified as associate nurses. The reform of nurse education in Kyrgyzstan started in 2021 and is based on European standards for nurse education. The pilot study programme for nurses represents the implementation of competencies for nurses in the EU Directive (2013). The pilot programme includes 2,300 hours of theoretical knowledge and 2,300 hours of clinical training. All clinical areas in theory and practice as outlined in the EFN guidelines (2015) were introduced. The new curriculum for nurse education was introduced in four pilot medical colleges in the academic year 2022/2023.

Aim of the study

In preparation for piloting the new curriculum, a survey among teachers and mentors at four schools was conducted in 2022 to determine their understanding of the reform and their attitudes that could significantly influence the success of the pilot phase of the new curriculum and nursing education reform as a whole.

Research question

What is the level of understanding and support for changes in the nursing curriculum among college teachers at four medical colleges in Kyrgyzstan?

METHODS

Research design

A cross-sectional, mixed study design was used. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected with a convergent parallel technique during the same phase of the research process. Data were analysed independently. After both analyses were completed, we compared our results to provide discussion and general conclusions (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). The STROBE combined checklist was followed for reporting the study.

Settings and sample

The pilot medical colleges involved are located in different regions of the country. The decision of which colleges will participate in the piloting of the reformed nursing education programme was adopted at the Ministry of Health of Kyrgyzstan which also supported the project of reforming the vocational diploma programme for nurses.

A cohort of all faculty (N = 150) at the four pilot colleges were included. The response rate was 93.34% (n = 140). The number of returned questionnaires per participating college ranged from 22 to 55. The sample included 123 (87.9%) women and 10 (7.1%) men; 7 respondents did not specify their gender. The mean age of the respondents was 50.79 years (SD = 10.74).

Instrument description

The questionnaire consisted of 10 groups of questions and statements. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. The questionnaire was developed to assess the planned reform of nursing education according to the European directives on the recognition of professional qualifications (Directive 2005; Directive 2013) and the Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery 2021–2025 (2021). A total of 23 statements were used to assess respondents’ attitudes towards contemporary views of nursing as a profession and a science and the relationship between physicians and nurses. The demographic set included age, gender, seniority, leadership position, area of professional training, level of training in the professional field, and work area. The quantitative groups of statements were: Nursing Education Requirements in Europe (6 statements, α = 0.813), Nursing Education Knowledge and Skills (5 statements, α = 0.918), Nursing Education Competencies (8 statements, α = 0.941), and Contemporary Views of Nursing as a Profession and a Science (23 statements, α = 0.958). Different scales were used, first a 5-point scale (1, do not agree at all; 2, do not agree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, agree; 5, fully agree); then a 4-point scale for needed for reform (1, definitely no; 2, probably no; 3, probably yes; 4, definitely yes); and a 5-point scale for support for the requirements described (1, do not agree at all; 2, do not agree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, agree; 5, fully agree). Some questions with nominal answers (yes, no) were also posed.

An open-ended question was added to each group of statements or topics that were different in nature. In addition to the closed response options, we were interested in what respondents wanted to add (seven open questions) on the topics from which the quantitative questions were drawn concerning the approach of nurse education in Europe, the need for international comparability of nurse education in Kyrgyzstan, support for curriculum reform in medical colleges, comments on the pilot curriculum, developmental dimensions of modern nursing and the situation in Kyrgyzstan.

Before collecting the data, content validation of the prepared questionnaire was carried out in Russian. Members of the local project team, college directors and their assistants participated in the validation process so that the questions could be formulated as comprehensively as possible.

Data collection

Data collection began at the end of March 2022 and ended in April 2022, using a paper-and-pencil method in which printed questionnaires were distributed to the colleges through coordinators designated by medical college management. The average response time was estimated at 15–20 minutes. The respondents were given seven days to complete the questionnaire. Respondents dropped the questionnaires off in a sealed envelope at the agreed collection point.

Ethical considerations

All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations: we followed the Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (The Norwegian 2021) and the Declaration of Helsinki (World 2013). The study did not require ethical approval with regard to national regulations in Kyrgyzstan, as it was not experimental research on humans, but rather a cross-sectional study of attitudes and values. Each college confirmed its participation by a decision of a relevant expert committee, the college's ethics committee or the college's expert committee (senate). Consent for publication in scientific journals (online, open-access) was also obtained. Participants received written information about the various aspects of the study; they were informed of their rights to participate voluntarily and to withdraw from the study at any time, as well as their rights to privacy and confidentiality. Participants also provided written informed consent to participate in the study and permission to use data collected at the national level for professional purposes, purposes concerning reform development and scientific purposes.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS 22 statistical software. Basic descriptive, univariate and bivariate statistical analyses were performed. Reliability tests were performed for all quantitative statements with an ordinal scale. A mean substitution was used, with the mean value of a variable used in place of the missing data value for that same variable. This allows the researchers to utilise the collected data in an incomplete dataset.

A qualitative content analysis approach was used to analyse the qualitative data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). An editorial analysis was used to classify the common content. The unit of coding was a written thought or stated position (a selective approach) on a particular topic. Coding was done using a thematic coding technique (Gomm, 2008), that is, codes consisted of multiple words with the goal of describing the essential content of what was said, which is referred to as open descriptive coding. If a writer touched upon several topics, we coded that separately, according to the topic. This allowed us to create categories as superscripts of the codes at the contextual level, to complement the categorisation scheme and to develop the key findings which, based on our interpretation, we presented in the form of superscripts of the codes, categories and themes—the latent content (Lindgren et al., 2020). In formulating themes, we followed Polit and Beck's (2008) definition: A theme is an abstract entity that gives meaning and identity to a current experience and its various manifestations. As such, a theme captures and unifies the nature or basis of the experience into a meaningful whole. The final themes, categories and codes were developed based on a consensus approach within the research team. The group that analysed qualitative data consisted of three experts in healthcare education and development projects in the healthcare system, and one person that acted as an administrative assistant.

Rigour and trustworthiness

In this article, we show how data analysis was conducted by collecting data, systematising and disclosing the methods of analysis in sufficient detail to allow the reader to determine whether the process is credible. We followed the findings to achieve rigour and trustworthiness according to Nowell et al. (2017). The concept of reliability was achieved by introducing the criteria of credibility (data collection and triangulation by the researcher to verify findings and interpretations with participants), transferability (use of case-to-case transferability) and dependability (clearly documented) to achieve confirmability of the research.

RESULTS

Participants

The sample included 45 (32.1%) respondents from nursing, 59 (42.1%) from medicine and 16 (11.4%) from other fields of social or natural sciences. In terms of educational achievement, 19 (14.4%) respondents had a secondary school degree, 112 (84.8%) had a bachelor's degree and 1 (1.08%) person had a master's or doctoral degree. According to undergraduate education, 45 (31.1%) were nurses, 59 (42.1%) were physicians and 16 (11.4%) had other education, while 20 (14.3%) participants did not answer this question. An important fact is that in one of the pilot medical colleges, 63.6% (n = 35) of teachers were physicians, while in the remaining three participating colleges, this proportion was smaller, ranging between 23% and 38%. As a result, this participating medical college had fewer teachers who were nurses in the study. Thus, the share of nurses involved as a teacher varied from 16.4% to 51.7%.

Almost all (96.2%) respondents were employed full-time. A total of 105 (75%) were from medical colleges and 20 (14.3%) were from healthcare institutions and worked part-time for colleges. The position of leader (directors, head of the nursing department, head of clinical supervision, head of modules in study programme) was held by 101 (72.1%) respondents; 15 (10.7%) did not answer this question. On average, 10% of respondents did not provide complete sociodemographic information.

Results of quantitative data

Only 56.4% (n = 79) of the respondents were familiar with the European approach to nurse education. There were significant differences between participating colleges (χ2 = 56.669; p < 0.001), as the proportion of those that were familiar with the European approach ranged from 23.6% to 96.6%. The type of education received was also significant (χ2 = 17.288; p < 0.001), as respondents educated in nursing expressed familiarity at 73.3%, compared to respondents from medicine at 40.7%, and others at 68.8%. Leaders were more informed regarding the education of nurses in Europe (67.3%) compared to others (25%) (p < 0.001). The level of education did not have an impact on this question.

The mean agreement with the proposed statement ‘Nurse education in your country needs to be aligned with international guidelines’ was 3.12 (SD = 1.09) on a 4-point scale (1, definitely no; 4, definitely yes). The proportion of probably yes and definitely yes was 70.7%. A total of 131 (93.6%) responses to this statement were obtained. There were significant differences between colleges (F = 32.937, p < 0.001), as in one college, the proportion of answer ‘definitely yes’ was 36.3%, while it ranged from 90.9% to 96.6% for the other three colleges. In terms of professional education, respondents from medicine expressed lower agreement (M = 2.68, SD = 1.24, F = 11.489, p < 0.001) compared to nursing respondents (M = 3.60, SD = 0.58) and others (M = 3.43, SD = 0.76). The differences in the level of education were not significant.

We found a high level of agreement with the six written requirements for nurses’ education in the EU (Table 1). The reliability of statements was good (α = 0.813, n = 6), and the lowest agreement was with the number of hours of the curriculum and clinical practice. One college scored significantly lower on all requirements compared to the other three (p < 0.001).

| General requirements for education of nurses responsible for general care in EU member states | n | M | SD | Probably yes and definitely yes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total duration of education is at least three years of study. | 130 | 3.577 | 0.735 | 86.5 |

| 2. The education shall include at least 4,600 hours of theoretical and clinical training. | 125 | 3.360 | 0.846 | 75 |

| 3. Clinical education must include at least 2,300 hours of clinical practice in health care facilities. | 128 | 3.156 | 0.909 | 74.3 |

| 4. Theoretical education is provided by teachers of nursing and other competent persons at universities and colleges of recognised equivalent level. | 133 | 3.436 | 0.856 | 83.6 |

| 5. Clinical education: Students learn in direct contact with a healthy or ill person and/or community, and assess what comprehensive nursing care is needed based on the knowledge, skills and competences acquired. | 135 | 3.526 | 0.645 | 91.4 |

| 6. Clinical education: Students learn not only to work as part of a team, but also to lead a team and organise comprehensive nursing care, including health education for individuals and small groups in a health care facility or community. | 135 | 3.296 | 0.773 | 83.6 |

- Note: M, mean value; SD, standard deviation; p, the mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level; scale: definitely no (1), probably no (2), probably yes (3) and definitely yes (4).

There was a high level of agreement with the achievement of nursing education competencies prescribed by the EU in the actual Kyrgyz curriculum at four medical colleges (Table 2). The reliability of statements was very good (α = 0.941, n = 8). The lowest agreement was established for the ability to independently assure and evaluate the quality of nursing care (f). One college scored significantly lower on all competencies compared to the other three (p < 0.001).

| Competences of nurses after having completed training for general care nurses in the EU | n | M | SD | Probably yes and definitely yes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) The ability to determine independently what nursing care is required, using existing theoretical and clinical knowledge, and to plan, organise and implement nursing care in the treatment of patients | 133 | 3.459 | 0.774 | 88.6 |

| (b) The ability to collaborate effectively with other actors in the health sector, including participation in the practical training of health personnel | 129 | 3.411 | 0.735 | 82.9 |

| (c) The ability to train individuals, families and groups in healthy lifestyles and self-care | 133 | 3.556 | 0.712 | 87.2 |

| (d) The ability to independently initiate immediate life-sustaining measures and to act in crisis and emergency situations | 127 | 3.354 | 0.782 | 80.7 |

| (e) The ability to independently counsel, guide and support persons in need of care and their relatives | 128 | 3.305 | 0.819 | 79.3 |

| (f) The ability to independently assure and evaluate the quality of nursing care | 125 | 3.336 | 0.842 | 77.8 |

| (g) The ability to communicate and collaborate with other healthcare professions in an integrated professional manner | 132 | 3.326 | 0.806 | 84.3 |

| (h) The ability to evaluate the quality of nursing care with a view to improving their professional practice as a nurse responsible for general nursing | 131 | 3.466 | 0.871 | 81.4 |

- Note: M, mean value; SD, standard deviation; p, the mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level; scale: definitely no (1), probably no (2), probably yes (3), definitely yes (4).

The agreement to support EU requirements and competencies for nurses’ education in the Kyrgyzstan curriculum at medical colleges was lower (3.51, SD = 1.13, n = 137) than the general agreement with EU recommendations described above. Again, significant differences between the participating colleges were established (F = 34.753, p < 0.001), with one college expressing support in 41.8% and the other three from 85.2% to 96.5% (agree, strongly agree).

Generally, the mean support of respondents for EU requirements and competencies for education of nurses was good, equalling 3.85 (SD = 0.91). The proportion of answers ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ was 75.7%. There were significant differences between participating colleges (F = 10.037, p < 0.001), with one college expressing mean agreement at the level 3.37 (SD = 1.15) and the other three between 4.10 (SD = 0.31) and 4.23 (SD = 0.46). The group of leaders revealed higher agreement (M = 3.99, SD = 0.72, p = 0.021).

We were interested in respondents’ attitudes towards contemporary views of nursing as a profession and a science in three areas: education, competencies and development, and interprofessional collaboration. The descriptive results of 23 statements (α = 0.958) and a comparison between colleges are shown in Table 3.

| Statements | n | M | SD | Probably yes and definitely yes (%) |

Colleges p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education of nurses (α = 0.902) | |||||

| 1. Teachers at nursing programmes are mostly nurses with academic careers. | 126 | 2.675 | 1.109 | 22.9 | <0.001 |

| 2. Nurses are also deans or directors of nursing colleges. | 128 | 2.406 | 1.090 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| 3. The relationship between the teachers who are nurses, doctors and other professionals is respectful and equal. | 131 | 3.893 | 0.777 | 77.9 | 0.001 |

| 4. The college actively cooperates with healthcare institutions and arranges clinical training for students. | 131 | 4.183 | 0.812 | 84.5 | <0.001 |

| 5. National regulation requires cooperation between colleges and healthcare institutions. | 130 | 4.108 | 0.750 | 85 | 0.023 |

| 6. The educational institution must set the conditions for who can be a clinical mentor to students in the healthcare setting and must provide regular education and training for clinical mentors. | 128 | 3.578 | 1.265 | 65 | <0.001 |

| 7. The clinical training process must be coordinated and managed by the college, which must lead the ongoing and final evaluation process for both students and clinical supervisors. | 130 | 4.192 | 0.855 | 81.4 | <0.001 |

| 8. The clinical mentor ratio is one to one, with a maximum of two students per mentor. | 129 | 3.132 | 1.128 | 42.2 | <0.001 |

| 9. Clinical mentors are co-responsible for the level of knowledge, skills and competencies achieved by the graduate, which is linked to the process of training and development of mentors and the involvement of mentors in theoretical education at the colleges. | 126 | 3.627 | 1.041 | 62.6 | <0.001 |

| 10. Subjects with clinical content, such as Chronic Disease Nursing, are taught in equal collaboration between the Chronic Disease Nursing Teacher (nurse) and the Internal Medicine Teacher (doctor). | 129 | 3.543 | 1.068 | 65.7 | <0.001 |

| Together | 3.518 | 0.752 | |||

| Competences and professional development (α = 0.909) | |||||

| 11. In developed countries, nurses are educated at higher education levels and have the opportunity to specialise clinically and work independently at the primary level, which requires a master's degree. | 129 | 3.271 | 1.191 | 53.6 | <0.001 |

| 12. Nurses’ competencies are at several levels: (1) nurse assistant, (2) registered nurse, (3) specialised nurse, (4) clinical nurse specialist or advanced nurse practitioner. | 125 | 3.168 | 1.243 | 38.6 | <0.001 |

| 13. Nurses are members of hospital management. | 128 | 3.320 | 1.136 | 48.6 | <0.001 |

| 14. Nurses are involved in national development projects to develop the national health system. | 129 | 3.814 | 0.882 | 68.6 | <0.001 |

| 15. Nurses are directors of healthcare institutions. | 128 | 2.508 | 1.210 | 20.7 | <0.001 |

| 16. Nurses with master's degrees and PhD are researchers and candidates for national and international research projects. | 130 | 3.000 | 1.194 | 39.3 | <0.001 |

| Together | 3.178 | 0.953 | |||

| Relationship between physicians and nurses (α = 0.961) | |||||

| 17. Physicians value nurses’ observations and judgements. | 124 | 3.790 | 0.922 | 68.6 | <0.001 |

| 18. Physicians hold nurses in high esteem. | 119 | 3.782 | 0.875 | 61.2 | <0.001 |

| 19. Physicians recognise nurses’ contributions to patient care. | 126 | 4.087 | 0.705 | 81.4 | <0.001 |

| 20. Physicians respect nurses as professionals. | 130 | 4.062 | 0.755 | 82.8 | <0.001 |

| 21. Physicians and nurses have good working relationships. | 132 | 4.129 | 0.703 | 86.4 | 0.021 |

| 22. Collaboration between nurses and physicians is very good. | 131 | 4.122 | 0.691 | 86.5 | 0.015 |

| 23. A lot of teamwork between nurses and physicians is recognised. | 132 | 4.121 | 0.688 | 85.7 | 0.012 |

| Together | 4.026 | 0.699 | |||

- Note: M, mean value; SD, standard deviation; p, the mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level; scale, strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5).

Results for the area of education in Table 3 revealed very low agreement with statements 1 and 2 and low agreement with statement 8. For competencies and professional development of nurses, low agreement with statement 15 and indecision for statements 16 and 12 were established, as well as weak agreement for statements 13 and 11. For the last part of Table 3—interprofessional collaboration—results are given based on the relationship between physicians and nurses. The scores are slightly lower for statements 17 and 18, but when looking at the set of statements in its entirety, this set has the highest average score. Respondents were undecided about the competencies and professional development of nurses. Adoption of modern approaches in nursing education seems to be shifting from indecision towards agreement.

Results of qualitative data

As part of the questionnaire, respondents were also asked at seven points to comment on the topics from which the quantitative questions were drawn. Thus, we received a total of 180 written comments. We formed 57 superscripts of the codes, and some of which appeared several times. For this article, we selected the three most representative ones which are shown in Figure 1. A total of 14 codes and 5 categories were developed. Finally, we summarised two themes as drivers and barriers to reform (Figure 1).

The codes developed reached a good content and allowed us to add meaning to the comments made, as we identified three opportunities that can strengthen the implementation of the reform, and also two barriers. We have followed the findings to achieve rigour and trustworthiness according to Nowell et al. (2017).

DISCUSSION

The survey provides a glimpse into the state of readiness and commitment of faculty at four pilot medical colleges in Kyrgyzstan for nursing education reform currently underway at these colleges. The findings of the research should be understood based on the fact that the providers and leaders of nursing education in the involved pilot colleges are largely physicians. In one of the participating medical colleges, the sample included as many as 64% of physicians, which is why there are also some deviations in comparisons between colleges.

Slightly more than half of the respondents were aware of the unified education in European countries according to EU Directives (2005, 2013); nearly three-quarters of faculty supported the reform, but there was a wide dispersion of responses. Significantly, knowledge of and support for the reform were higher among respondents with a degree in nursing, while respondents with a medical degree showed less support. Given the weak development of nursing in Kyrgyzstan, this is consistent with the well-known fact that nursing is often still dominated by physicians. Physicians take a paternal and directive role, while nurses follow suit (Migotto et al., 2019).

Agreement with the basic requirements of the European guideline (Directives 2005, 2013) for general nursing education was over 80%, while agreement with the proposed scope of clinical practice, that is, working directly with patients in health care settings and under the supervision of mentors, was lower. The scope of proposed clinical education is also analysed and problematised in European countries and elsewhere (Gobbi & Kaunonen, 2018; Henriksen et al., 2020; Potter, 2021). Also, it is very important that patients are discharged from hospitals earlier and that the number of hospital beds in wards is reduced (Henriksen et al., 2020); as a result, the number of clinical training opportunities for students has decreased. Potter et al. (2021) found no discernible relationship between the minimum number of practice hours and student performance on the national exam in the United States.

Regarding the competencies in the European Directive (2013) and their recognition in the current Kyrgyz curriculum, the surprising finding of the survey is that respondents believe they are already achieving them; however, a review of course descriptions conducted by a group of experts as part of a development project did not reveal this (Skela-Savič, 2023). This could be attributed to the technique of self-report, which is defined as a systematic error resulting from differences in the implicit standards by which individuals evaluate their behaviour. This recognition suggests that standards for self-regulation vary by social group, which limits the political application of self-report questionnaires (Lira et al., 2022). The second limitation that needs to be considered in this discussion is that the sample consisted mostly of leaders who may, at the conscious and unconscious levels, think that the current programme is a good one.

The survey revealed low support for the fact that the majority of teachers in nursing programmes should be nurses with academic careers. There was even less support for the notion that academically trained nurses also act as deans of colleges and faculties. Conversely, two-thirds of respondents supported the inclusion of nurses in university faculty for theoretical subjects. A clear definition of the role of nurses in the delivery of the teaching process and the leadership of nursing schools was established years ago in the Munich Declaration (WHO, 2000), which defines the standard for the education of nurses and midwives in WHO Europe. Our respondents reported that both colleges and healthcare institutions have an awareness of the importance of mentoring and accountability, but one-to-one mentoring was supported by only 42% of respondents, and extensive work is still needed in this area to reach the standard of the Munich Declaration (WHO, 2000), the European guidelines (Directives 2005, 2013), and the latest standards developed by European countries (Campos Silva et al., 2022; Collier-Sewell et al., 2023; Eronen et al., 2023; Gobbi & Kaunonen, 2018) and global orientations for nursing education (Baker et al., 2021). Since more than 80% of respondents confirmed good collaboration with healthcare institutions, this resource should be used in the reform of nursing education.

In the area of nursing competencies and professional development, the results were not encouraging. The multilevel competency models presented by ICN (2008) and EFN (2023) and the subject of recommendations in strategic documents (Global, 2021) were accepted by less than 40% of respondents, as was the role of research in nursing. Respondents do not envisage nurse education at all three levels of higher education (bachelor's, master's, and PhD levels), and even fewer recognise nurses as leaders of healthcare institutions. Relationships between nurses and physicians were rated as good, yet the lowest level of agreement was obtained for the statement that physicians value nurses’ judgement.

A qualitative analysis of the written comments confirmed some of the quantitative findings and identified other important dimensions of factors that may promote or inhibit nursing education reform in Kyrgyzstan. Namely, we found that respondents were positive about the reform of nursing education and supportive of the bachelor's degree programme, so it makes sense to follow European standards in this regard, but at the same time an equally strong dimension of this reform is respect for the local perspective, which emerges as the importance of the history of education, poor economic situation in the country, local mentality that is not very conducive to the development of nursing, and, finally, respect for the laws and regulations of the Kyrgyz state. It was also recognised that existing training has limitations that need to be overcome. The importance of the local environment in reforming nurse education has been highlighted by several authors (Farsi et al., 2022; Fawaz et al., 2018; Petry et al., 2021).

Implications for nursing

Nurses are not recognised in development and leadership roles, indicating a subordinate view of the nursing profession which acts as a limitation to its development. Changing this attitude towards nursing will require a major effort on the part of nurses, doctors and their national organisations, healthcare decision-makers at the state level and binding incentives from international organisations such as WHO Europe.

Implications for health policy

Like any development work, this reform has its limitations which are reflected in the lack of recognition of nursing as an extremely important profession in the health system that needs development, as highlighted by international organisations, forums, guidelines, documents, etc. (EFN, 2023; Global, 2021; ICN, 2015; Wong et al., 2015). This misunderstanding and negative attitude toward the role of nurses in the healthcare system are evident in both the quantitative and qualitative sections of the study. There is little recognition of the need for skills and career development of nurses, a lot needs to be done to build confidence in the reforms and to demonstrate the relevance of the international guidelines to Kyrgyzstan.

Limitations

The results are limited to the opinions of the respondents. A higher response rate would be desirable. One of the limitations is that around 10% of the respondents did not want to provide full demographic details, which has an impact on comparisons in terms of demographics. In the case of missing values that are not strictly random, the mean substitution method can lead to inconsistent distortions. The results of this study are limited to the responses of respondents working at the colleges selected for the pilot project and cannot be generalised to all public medical colleges in Kyrgyzstan. It is possible that respondents were overly positive or negative about nursing education reform. Finally, the accuracy of self-report surveys may be limited.

CONCLUSION

The perceived attitudes of the respondents are not the most encouraging for nursing education reform in Kyrgyzstan, but they provide good insight into the current situation and a basis for future directions. To prepare future highly qualified nurses who are more versatile for the coming changes and advances, Kyrgyz nursing education is expected to be reviewed and revised in light of modern and current standards of nursing education. More attention should be paid to research, teaching and assessment methods by adopting the experiences of other countries with an adequate and successful education system. It is necessary to promote the development of nursing teachers and heads of nursing departments who should be nurses with undergraduate and postgraduate education. Finally, the impact of the pilot curriculum use should be studied, since in this case only one side was heard, while also students need to be listened to in order to gain a comprehensive picture.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: Brigita Skela-Savič, Bruno Lab, Altynai Mambetova, Gulzat Orozalieva; data collection: Altynai Mambetova, Burulcha Rustamova, Gulzat Orozalieva; data analysis: Brigita Skela-Savič, Altynai Mambetova, Burulcha Rustamova, Gulzat Orozalieva; study supervision: Brigita Skela-Savič, Bruno Lab, Olivia Heller, Kathrine Zimmermann, Marina Giachino, Gulzat Orozalieva, Altynai Mambetova, Nurida Zhusupbekova; manuscript writing: Brigita Skela-Savič, Bruno Lab, Olivia Heller, Kathrine Zimmermann, Marina Giachino, Nurida Zhusupbekova; critical revisions for important intellectual content: Bruno Lab, Olivia Heller, Kathrine Zimmermann, Marina Giachino, Nurida Zhusupbekova.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all those involved in this study for their support. In particular, the directors of the four medical colleges (Bishkek Medical College, Tokmok Medical College, Naryn Medical College and Uzgen International Medical College of OshSU) for allowing access to the faculties and departments. We would like to thank the faculty members who agreed to participate in the survey and give their valuable time. Special thanks to the Ministry of Health, the Swiss Embassy in the Kyrgyz Republic and the Kyrgyz Nurses Association (KNA) for their support in the nursing reform. The study was undertaken as part of the Medical Education Reforms (MER) project, Phase III, which is funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). Credit Proposal nr 7F-08530.03.0. Contract nr. 81070462.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

PERMISSION TO USE, MODIFY OR TRANSLATE SCALES IN THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Permission was not required. The questionnaire was developed by the authors to assess the planned reform of nursing education according to the literature described in the description of the instrument (Directive 2005; Directive 2013; Global 2021).