Administration of chemotherapy with palliative intent in the last 30 days of life: the balance between palliation and chemotherapy

Abstract

Background

Appropriately timed cessation of chemotherapy is an important aspect of good quality palliative care. There is wide variation in the reported rates of chemotherapy administration within the last 30 days of life.

Aims

To identify predictors of death within 30 days of receiving palliative chemotherapy, and to propose a standard definition by which oncologists and cancer centres can be compared.

Methods

Patients who received palliative chemotherapy at a regional cancer centre and its rural outreach unit between 2009 and 2011 were included. An adjusted logistic regression model, including all variables, was fit to identify predictors of death within 30 days of receiving palliative chemotherapy.

Results

Over a 3-year period, 1131 patients received palliative chemotherapy, 138 (12%) died within 30 days of receiving palliative chemotherapy. Predictors of death within 30 days of palliative chemotherapy were: less than 30 days contact with palliative care (odds ratio 3.30 (95% confidence interval 2.04–5.34), P < 0.001) and male gender (odds ratio 2.02 (95% confidence interval 1.24–3.31), P = 0.0049), but treating clinician, tumour chemoresponsiveness, age, body mass index and survival from initial diagnosis were not.

Conclusion

Patients who received chemotherapy in the last 30 days of life were more likely to be male and have a shorter duration of palliative care team involvement. In this study, the observed rate of death within 30 days of chemotherapy is within the range of published data. It is recommended that a standard definition be used to benchmark medical oncology centres and individual oncologists, and to allow comparison over time.

Introduction

Improvements in the efficacy of palliative chemotherapy has resulted in prolonged overall survival, progression-free survival and improved quality of life for patients with incurable cancer. A proportion of these patients can be considered to have a chronic illness, and have many lines of effective chemotherapy available to them.1 Prolonged survival means that patients may receive chemotherapy for longer periods of time, and nowadays, a broader range of cancer types have active treatments. The benefits are often considered well worthwhile to those patients who are contemplating their last months of life, despite the risk of adverse effects.2 Toxicity may adversely impact on quality of life during a time when quality of life is frequently prioritised.3 The public profile of cancer research has also risen, which can engender high patient expectations.4 In all but the most chemotherapy-responsive tumours, it is considered inappropriate to give chemotherapy if death is anticipated in the near future. If a patient has poor performance status because of a chemoresponsive tumour such as small cell lung cancer, lymphoma or a germ cell tumour, then chemotherapy has the potential to reverse the process rapidly in a proportion of patients, leading to substantial quality of life and survival benefits, and possibly cure.5

Chemotherapy that continues until close to the end of life has an adverse impact on many patients' quality of life, time and finances. The rate of death within 30 days of chemotherapy has been increasingly acknowledged as an indicator of quality care.6 The European Society of Medical Oncology and the American Society of Clinical Oncology have published position statements on the use of chemotherapy at the end of life, recommending discussions about appropriate cessation of chemotherapy.7, 8 Despite these, along with other publications calling for specific guidelines,6, 9 a firm cut-point is not in widespread use as a marker of quality of care. Different criteria have been used to define the population of interest, including the rate of death within 30 days of chemotherapy as a proportion of: all patients seen; all patients given chemotherapy; all patients with advanced incurable disease seen and all patients with advanced incurable disease given chemotherapy. A duration of either 14 or 30 days has been selected by the majority of studies investigating this issue.

The inclusion criteria of the studies that have previously reported on this subject are heterogeneous, which makes comparison of reported death rates difficult (Table 1).6, 10-18 Tumour types varied: Näppä et al.17 included only epithelial malignancies, Kao et al.16 excluded those with a haematological malignancy, Yoong et al.18 included all malignancies except acute leukaemia, Earle et al.11 included patients with lung, breast and gastrointestinal cancers, while Murillo et al.14 included only those with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and Asola et al.12 restricted inclusion to patients with advanced breast cancer. Most studies only included patients with advanced cancer; however, Yoong et al.,18 O'Brien et al.6 and Barbera et al.13 included all patients treated for cancer. Large registry-based studies from the USA10, 11 and Canada13 did not report whether the treatment intent was curative or palliative. The studies from the USA by Earle et al. and Emanuel et al. included patients who were given chemotherapy between 1993 and 1996, which makes the data difficult to compare with modern chemotherapy regimens.10, 11

| Study | Patient groupa | Number | Year | Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 week | 4 week | ||||

| Emanuel et al.,10 USA | Fee-for service Medicare, receiving chemotherapy with palliative intent, aged >65 years | 7919 | 2003 | — | 9 |

| Earle et al.,11 USA | Chemotherapy given with palliative intent, SEER database, Medicare, aged >65 years | 28 777 | 2004 | 18.5 | — |

| Barbera et al.,13 Canada | Patients who received chemotherapy in the last 6 months of life, Ontario cancer registry | 22 544 | 2006 | 4.2 | 16 |

| O'Brien, et al.,6 United Kingdom | All patients who received chemotherapy | 1976 | 2006 | — | 8.1 |

| Murillo et al.,14 USA | Community NSCLC who received chemotherapy | 417 | 2006 | 20 | 43 |

| Asola et al.,12 Finland | Advanced breast cancer treated with chemotherapy | 335 | 2006 | — | 19.7 |

| Earle et al.,15 USA | Younger patients with health insurance | 18 812 | 2008 | 17.1 | — |

| Kao et al.,16 Australia | All patients with advanced incurable malignancy | 747 | 2009 | 8 | 18 |

| Nappa et al.,17 Sweden | Patients given chemotherapy with palliative intent | 374 | 2011 | — | 23 |

| Yoong et al.,18 Australia | All patients treated with chemotherapy | 378 | 2012 | — | 3.4 |

| Zdenkowski et al., Australia | Patients given chemotherapy with palliative intent | 1131 | 2013 | — | 12.2 |

- —, Not reported.

Published rates of death within 2–4 weeks of chemotherapy vary widely, between 3.4 and 43%, depending on the definition used and the characteristics of the patients (Table 1). The optimal rate is not zero, which would imply undertreatment, because not all deaths are predictable. Oncologists, however, should be able to cease chemotherapy at an appropriate time-point for the majority of patients in order to optimise quality of life, and avoid excess harm. Prognostication is an important part of the decision to cease chemotherapy, but is often a subjective estimate.19 There is evidence that early involvement from a palliative care team (PCT) has an impact on survival and quality of life, and contributes to less aggressive care at the end of life.20

The aims of the present study were to determine if there were patient-, tumour- or clinician-related factors that would predict for death within 30 days of receiving chemotherapy with palliative intent, and to report the rate to enable units and clinicians to be compared. The rate of death within 30 days of palliative chemotherapy is proposed as a clinical governance performance measure.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was undertaken using the Aria Medical Oncology electronic medical record system. Patients were included if they had received a dose of chemotherapy within the period including 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2011, at the Calvary Mater Newcastle Hospital, or Manning Base Hospital, its rural outreach hospital. These hospitals are serviced by a single medical oncology department and a palliative care service that manages a hospice and outreach services to local and regional communities. Intravenous and oral anticancer therapies, including cytotoxic and biological agents, were included. Endocrine therapy was not included. Epithelial malignancies, melanoma and lymphoma were included. The injectable bone modifying agent zoledronic acid was included because of the potential negative impact on quality of life for patients attending the day chemotherapy unit for intravenous therapy and the potential for acute toxicity. Survival was measured until 31 January 2012. Death data were extracted by a data manager from an area-wide patient administration database, confirmed through cross-referencing with the palliative care database and community health records.

Patients' treatment intent was recorded as curative, palliative or unknown, based on whether the treating clinician had specified intent, had applied a curative or palliative intent chemotherapy protocol, or the patient was being treated for metastatic disease. The Aria electronic medical record has a field where clinicians can indicate treatment intent as being curative, palliative or unknown, when a new course of chemotherapy is being started. A manual chart review was undertaken, to assign treatment intent to those in whom the treatment intent remained unknown, or for those with diagnoses where metastatic disease is potentially curable (such as germ cell tumours or lymphoma). The variables recorded were: gender, date of birth, height, weight, date of cancer diagnosis, date of last dose of chemotherapy, date of death, treating clinician, tumour origin and histology, chemotherapy regimen, cycle 1 of a course vs cycle 2 onwards, involvement of the PCT and duration of PCT involvement. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status is not routinely entered into the database, so it could not be used as a predictor. Tumour type was divided into chemotherapy responsive – those with a response rate of 50% or more with first-line chemotherapy (germ cell, lymphoma, ovarian, breast, colorectal, small cell lung) and non-chemoresponsive tumours (all other tumour types) in line with previous studies.16, 17 The database was cross-referenced with the palliative care database, which covers the same geographic area, to determine which patients had been seen by the palliative care service and the duration of contact.

The percentage of patients who died within 30 days was calculated as a proportion of the total number who had received chemotherapy with palliative intent. Initially, the model did not adjust for involvement of palliative care. A second model included all variables. A set of summary tables will be presented to provide descriptive statistics by outcome for the variables of interest. Continuous data will be summarised using the mean and standard deviation. Categorical data will be summarised as counts and percentages of each category. An adjusted logistic regression model, including all variables, was fit to identify predictors of death within 30 days of receiving a dose of chemotherapy with palliative intent. All predictors were included except for tumour type, which had a large number of zero counts. A P-value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

All statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and STATA (version 11.2; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) computer packages. Because this study was a quality assurance project, the Hunter New England Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee granted an exemption from formal ethics committee review.

Results

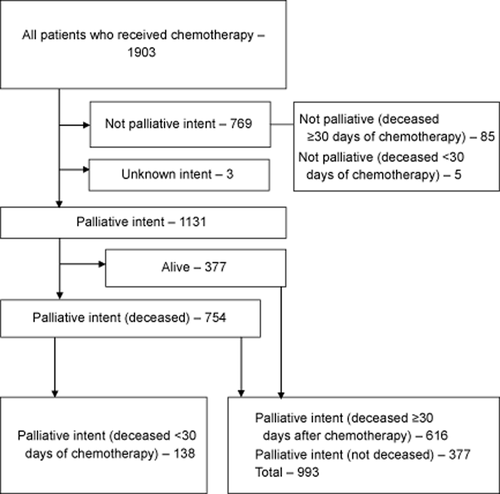

Eight medical oncologists had prescribed chemotherapy during this period, two of whom were categorised as ‘others’ because of the small number of patients treated individually. One thousand nine hundred and three patients were identified as having received at least one cycle of chemotherapy at one of two institutions between 2009 and 2011 inclusive. One thousand one hundred and thirty-one (59.4%) received chemotherapy with palliative intent, and for 3 (0.2%) patients, the intent was unknown. Of the 1131 patients, 138 (12.2%) died within 30 days of receiving chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Forty-two (3.7%) patients died within 30 days of the first cycle of a new course of chemotherapy. Of 1131 who received palliative chemotherapy, 714 (63.1%), 293 (25.9%) and 124 (11.0%) were on 1st, 2nd and ≥3rd line therapies, respectively, as the most recent chemotherapy received at the data cut-off. In the 138 who died within 30 days of chemotherapy, 86 (62.3%), 41 (29.7%) and 11 (8.0%), were on 1st, 2nd and ≥3rd line therapies respectively. A majority of these patients had extensive metastatic disease, and most were symptomatic of their cancer; however, incomplete medical record data precluded the use of these factors as predictors.

Flow diagram.

Equivalent numbers of males and females received chemotherapy with palliative intent, but of those who died within 30 days, 65% were male (Table 2). Sixteen per cent of males, compared with 8.8% of females, who received chemotherapy with palliative intent died within 30 days. The adjusted logistic regression model showed males had increased odds of death compared with females (odds ratio (OR) = 1.97 (1.2–3.3), P = 0.0083). There was a wide range of body mass index (BMI) observed, from 13 to 52 kg/m2, which was not associated with the rate of death after chemotherapy (P = 0.8641). Age, body surface area and time since cancer diagnosis were also not associated with death within 30 days of palliative chemotherapy. Zoledronic acid was received by 140 patients (7.4%), three of whom died within 30 days of receiving a dose.

| Outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Alive at 30 days (n = 993) | Died at 30 days (n = 138) | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted P-value |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 63.9 (11.8) | 63.9 (11.4) | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 0.8482 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Mean (SD) | 25.7 (5.8) | 25.7 (6.6) | 1.00 | 0.96-1.06 | 0.8641 |

| BSA (m2) | Mean (SD) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.16 | 0.21-6.49 | 0.8665 |

| Survival (years) | Mean (SD) | 2.5 (4.1) | 2.0 (3.4) | 0.98 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.4504 |

| Gender | F | 511 (91%) | 49 (8.8%) | 1 | — | 0.0083 |

| M | 482 (84%) | 89 (16%) | 1.97 | 1.19–3.27 | — | |

| Treating oncologist | Dr C | 256 (88%) | 36 (12%) | 1 | — | 0.1042 |

| Dr A | 113 (92%) | 10 (8.1%) | 0.54 | 0.25–1.16 | — | |

| Dr B | 145 (80%) | 37 (20%) | 1.40 | 0.82–2.39 | — | |

| Dr D | 74 (89%) | 9 (11%) | 1.03 | 0.46–2.31 | — | |

| Dr E | 188 (91%) | 19 (9.2%) | 0.62 | 0.34–1.15 | — | |

| Dr F | 144 (88%) | 20 (12%) | 0.88 | 0.48–1.63 | — | |

| Others | 73 (91%) | 7 (8.8%) | 0.65 | 0.27–1.56 | — | |

| Responsiveness to chemotherapy | Not responsive | 499 (87%) | 72 (13%) | 1 | — | 0.4291 |

| Responsive | 494 (88%) | 66 (12%) | 1.17 | 0.79–1.74 | — | |

| Palliative care | 30+ days | 338 (90%) | 39 (10%) | 1 | — | <.0001 |

| Less than 30 days | 124 (72%) | 49 (28%) | 3.30 | 2.04–5.34 | — | |

| No contact | 531 (91%) | 50 (8.6%) | 0.82 | 0.52–1.30 | — | |

- —, P-value represents the comparison with an index variable in categories of gender, treating clinician, chemo-responsiveness and involvement with palliative care. BMI, body mass index; BSA body surface area; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

In the multivariate model, treating clinician did not predict for death within 30 days of palliative chemotherapy (P = 0.10). However, when palliative care contact was removed from the multivariate model, treating clinician was a significant predictor (P = 0.025). Dr B prescribed palliative chemotherapy to 182 patients during the study period, of whom 37 (20%) died within 30 days of chemotherapy, representing the highest rate. Dr A prescribed chemotherapy to 113 patients, of whom 10 (8.1%) died within 30 days, representing the lowest rate. The adjusted ORs, compared with an index clinician (C), ranged from 0.54 to 1.40. This group includes clinicians at different career stages and who see patients with different tumour types.

Chemoresponsiveness of the primary tumour type did not predict for death within 30 days of chemotherapy (P = 0.4291). Of the patients with poorly chemoresponsive tumour types, 13% died within 30 days of chemotherapy with palliative intent, compared with 12% of those with chemoresponsive tumour types. Of the 42 patients who died within 30 days of their first cycle of chemotherapy, 66% had chemoresponsive tumour types. In decreasing order of frequency, the tumour types associated with death in close proximity to chemotherapy with palliative intent were head and neck cancer (21% of whom died within 30 days), small cell lung cancer (18%), haematological malignancies (17%), breast cancer (14%), upper gastrointestinal cancer (14%), non-small cell lung cancer (12%), sarcoma (11%), ovarian (9%) and prostate (6%). A group of histological diagnoses that did not have a primary site of origin recorded, which was designated as ‘other’, also had a high rate of death (27%). All other tumour types had a rate of less than 5%.

Almost half (550, 48.6%) of the patients who received chemotherapy with palliative intent were seen by the PCT (Table 3). Of those who were seen by the PCT, the median interval between initiation of contact and death was 77 days. Overall, 22% (124 of 550) had a duration of contact of less than 30 days between initial consultation and death. Of the patients who had less than 30 days contact with the PCT before death, 28% died within 30 days of chemotherapy, compared with 10% of those who had more than 30 days contact with the PCT. Palliative care is highly associated with the outcome, with patients who had less than 30 days contact having increased odds of death within 30 days of chemotherapy (OR 3.30 (2.04–5.34), P < 0.001). There was no difference in the rate of death within 30 days of palliative chemotherapy, between those who had no PCT contact and those who had more than 30 days contact (OR 0.82 (0.52–1.30)).

| Received chemotherapy with palliative intent | Died within 30 days of chemotherapy | Died within 30 days of 1st cycle of a new course of chemotherapy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seen by palliative care (%) | 550 of 1131 (48.6) | 91 of 144 (63.2) | 25 of 42 (59) |

| Died within 30 days from PCT contact (%) | 124 of 550 (22.5) | 51 of 91 (56.0) | 17 of 25 (68) |

| Median days between PCT contact and death (range) | 77 (0–1431) | 22 (0–849) | 18 (1–148) |

Discussion

Decision making about treatment for patients with advanced cancer involves consideration of the best available evidence and its application to an individual's circumstances.21 Patients vary in their wishes for intensive intervention towards the end of life, on a spectrum from symptomatic care, to wanting ‘everything done’.3, 22 Futility in cancer care is not well defined.23 Oncologists may be pressured by patients and family to continue chemotherapy, if only for a small chance of a benefit.21 Patients' goals at the end of life differ: some prioritise even a small survival gain, while a majority would accept chemotherapy for an improvement in quality of life and no survival benefit.24 Patients with dependent children are particularly willing to receive potentially toxic treatment.25 A high proportion of patients have inaccurate expectations about the potential benefits of palliative chemotherapy.26 Concordance is poor, between what patients want, and what physicians think patients want, when faced with decisions about advanced cancer.27 Also, third parties such as the media have a broad-reaching influence on patients' opinions, hope and confusion about cancer treatment.4

In our health service, referral to the PCT is commonly made while patients continue to receive medical oncology treatments. We hypothesised that contact with the PCT would lead to a lower rate of death within 30 days of receiving chemotherapy with palliative intent. In fact, the rate was relatively high: 20% of those who had PCT contact died within 30 days of chemotherapy, compared with 8.6% of those who had no contact. An explanation for this contradictory finding is that those who had more rapid disease progression could be both more likely to die within 30 days of chemotherapy and be more likely to have a late PCT referral, and therefore a shorter duration of PCT contact. Individual clinicians may be better able to develop a rapport with patients over time, and be able to refer their patients to the PCT at an earlier time, and to discuss cessation of chemotherapy, if appropriate. A proportion of patients do not have symptoms of sufficient severity to require specialist PCT support.28 The quality of the PCT involvement is at least as important as the quantity of time spent in contact with patients, to assist with end of life decisions such as the optimal timing of chemotherapy cessation. It was not within the scope of this study to assess directly the quality of the PCT input, so the duration of contact was used as a surrogate.

It is unclear why males were more likely to receive chemotherapy within 30 days of death. Men with cancer are less likely to express emotions which may impair physician–patient decision making.29 There may be an interaction between gender and individual tumour type, which was not controlled for in the statistical model. More work is required to ascertain whether patient, tumour or treating clinician-related factors are the reason for the discrepancy.

The finding of a trend towards variability between treating clinicians is consistent with previous studies.16, 30 Clinicians in this study varied by career stage, tumour types treated and in patterns of referral for palliative care consultation. Prognostic accuracy increases with increasing clinical experience, but remains inaccurate and overoptimistic.31 These clinician-specific factors were not part of the model in the current review. Treating clinician might be a surrogate for tumour type or tumour biology. There appears to be an association between treating clinician and which patients were seen by the PCT. In a study from the USA, oncologists gave a range of reasons for continuing chemotherapy towards the end of life: patient preference, increasing number of treatment options available, financial incentives, the small possibility of benefit and that there are barriers to end-of-life discussions.32 Financial reasons are considered less relevant in the Australian public health system. End-of-life discussions have been shown to reduce the likelihood that aggressive care is received in the last 30 days of life.33

The strengths of this study are the relatively large numbers within an institutional series, the ability to confidently assign treatment intent and the confidence that a large majority of patients' deaths were recorded accurately. It is limited by its retrospective nature, some missing data from those treated with oral agents, which was not recorded on the electronic prescribing software, and that the cause of death was not reliably entered into the database. ECOG performance status was not available, and may be a confounder. Because of relatively small numbers of patients treated by each clinician for individual tumour types, it was not possible to correct for tumour type by clinician. Accurate cause of death data would have allowed better interpretation of whether chemotherapy, advanced disease or other causes were contributing an excess number of deaths within 30 days of chemotherapy. Details of PCT involvement, such as the number and duration of individual consultations, provider (medical, nursing or allied health) and location (inpatient or outpatient) were not available. These details may have provided a better understanding of the quality care, rather than using time between initial contact and death as a crude proxy measure.

Oral biological agents were not included in this analysis because administration is not accurately captured in the electronic record. We hypothesise that because of ease of administration, and in some cases fewer toxicities, biological agents and oral agents will be more likely to be administered until closer to death. There may be good reason for such a practice, as cessation of some biologic agents, such as imatinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumour, results in rapidly progressive disease.34

Conclusion

The multivariate model shows that a shorter period of contact with the PCT, and male gender were associated with death within 30 days of palliative chemotherapy. Shorter duration of PCT involvement may represent late referral in patients erroneously considered fit for chemotherapy. Age, BMI, tumour chemoresponsiveness and survival from initial diagnosis did not predict for the outcome. The overall rate of chemotherapy administration with palliative intent (12.7%) is within the range of published data. The trends will be followed over time to measure quality of care within this organisational unit.

Critical reflection of one's practice, and comparison to colleagues locally, nationally and internationally are necessary to maintain a rational perspective on the way patients are managed. We encourage processes to be developed to enable rapid and meaningful data extraction and interpretation, to enable ongoing review of quality of care indicators such as this. Furthermore, a standard definition should be used to compare oncology units and to address specifically the issue of appropriate cessation of chemotherapy: the number of patients who die within 30 days as a proportion of those who receive chemotherapy with palliative intent.

References

- 1 Note heterogeneity of inclusion criteria