The phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ undermines analysis, policy and protection

Since 2015, the phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ has become a mainstay of policy discussions, media coverage and academic publications. The phrase is a cause for concern because it subtly undermines the meaning of ‘migrants’, with negative consequences for policy, analysis, and people on the move.

The heart of the matter is a disagreement over who ‘migrants’ are. Traditionally, policymakers, practitioners and scholars have understood an international migrant to be anyone who has moved away from their country of usual residence with the intention or expectation of staying for some time, irrespective of the reasons for migrating. Consequently, international students, oversees contract workers, refugees, and other groups with specific vulnerabilities and rights are included under the umbrella term ‘migrants’.

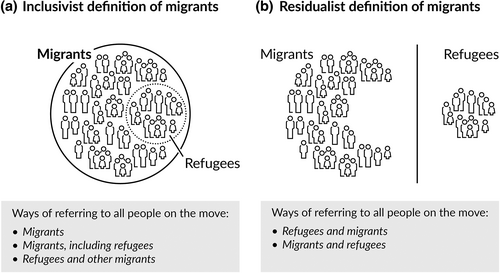

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR) has vehemently opposed this understanding. Specifically, UNHCR argues that refugees are not a subcategory of migrants. Rather, ‘migrants’ are understood as the residual, highly diverse group of all people on the move except refugees. Hence, we can denote the two definitions of ‘migrants’ inclusivist and residualist, respectively (Figure 1).

Importantly, the two views adhere to the same definition of refugees and recognize the distinctiveness of refugees and their rights; the only difference lies in whether or not ‘migrants’ include refugees.

The residualist view is dangerous for four reasons. First, it asserts that a migrant by definition is someone without a legitimate need for protection from persecution. But very often, when people cross borders, we cannot know their needs and rights. In fact, who is a refugee and who is not is sometimes established only after a lengthy individual status determination process.

Recognizing that every migrant might be a refugee is essential for the formulation of migration policy and border management. For instance, measures to combat migrant smuggling can go terribly wrong if migrants are understood as people who have no legitimate need to seek protection (Carling, 2017).

Second, the residualist view deprives us of an accurate and non-judgemental way of referring to diverse people on the move. The phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ seeks to do just that, you might argue. But using ‘refugees’ or ‘migrants’ on their own remains much more common. If we cannot use ‘migrants’ as an umbrella term that includes potential refugees, the result is often premature and prejudicial labelling.

A Nigerian arriving in Europe on a small boat is more likely to be called ‘migrant’ and a Syrian is more likely to be called ‘refugee’, even though both nationalities include people who are granted asylum and people who are not. With a residualist understanding of ‘migrants’, such labelling deprives the Nigerian of being seen as someone who might need protection.

Third, the exclusion of refugees from ‘migrants’ needlessly undermines important migration policy fields. Apart from migrant smuggling, the migration–development nexus and migrant integration are policy fields that must incorporate refugees as well as other migrants.

Fourth, only ‘migrants’ as an inclusive term can cover the diverse combinations of force and choice that shape migration both within and outside the refugee category (Erdal & Oeppen, 2018). While refugees are a legally distinct group, other migrants are not united by a shared experience of ‘choice’.

The seemingly innocuous phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ imposes the residualist view. Every time we use it, we reinforce the idea that ‘migrants’ excludes refugees.

Imagine a parallel scenario. We never say ‘roses and flowers’ because we understand roses to be one kind of flower. But that would change if rose suppliers pressured florists to change their signage to ‘Roses & Flowers’ and launched a sweeping public relations campaign with the slogan ‘Rose or Flower? Know the Difference!’ Our concept of flowers would whither—and more quickly so if we internalized the rose suppliers' view by starting to use the phrase ‘roses and flowers’.

The ‘rose supplier’ in the migration field is UNHCR. During the crisis of 2015–2016, it was clearer than ever that the words ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’ elicit divergent feelings of sympathy and hostility, respectively, among the public (Crawley & Skleparis, 2018). For an agency tasked with refugee protection, any association with ‘migrants’ or ‘migration’ could therefore be a liability. But, paradoxically, UNHCR's own persistent message that ‘migrants are not refugees’ fuelled the harmful effect of referring to people on the move as migrants.1

Right-wing politicians in Europe seized on the negativity of ‘migrants’ in descriptions of the crisis, with the result that using the word in its traditional, inclusive sense became seen as dehumanizing and xenophobic (Lazović, 2017).

There has also been another incentive for UNHCR to promote the residualist definition of migrants. Only by removing refugees from the larger group of migrants was it possible to retain UNHCR's exclusive ownership of refugees as a policy field in the organizational landscape. This became a pressing concern ahead of the International Organization of Migrations (IOM) joining the United Nations in 2016 and becoming ‘The UN Migration Agency’.

UNHCR has had remarkable strategic success as an increasingly influential agency (Crisp, 2020). The flipside of this feat is that the agency can be experienced as a somewhat bullish actor within the UN agency landscape. Despite the legacy of the inclusivist definition of migrants in the UN system, UNHCR has vigorously and successfully promoted a redefinition that partly reflects its special interests in inter-agency power struggles.

A major UNHCR campaign backed by celebrity advocates used the tagline ‘word choice matter’ to promote the idea that ‘migrants’, by definition, are not refugees. As one media story summed it up ‘These Celebrities Want You To Stop Using The Word “Migrant”’ (Hartley 2015). The coexistence of different definitions of ‘migrants’ was not presented as such. Instead, UNHCR's interpretation was cast as the only correct and compassionate usage. People who disagreed were implicitly branded as simpletons who don't appreciate that words matter. This rhetorical tactic is reminiscent of uncompromising political battles, as when opponents of abortion self-identify as ‘pro-life’ and thereby imply that their adversaries are ‘pro-death’.

The controversies around labelling made ‘refugees and migrants’ seem like a safe bet for journalists, commentators, and analysts. In 2015–2016 there was a spike in media coverage of migration issues, and while the words ‘refugees’ and ‘migrants’ were both used more frequently, it was the phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ that truly swelled (Figure 2). With a lag of a few years—reflecting the slower pace of scholarly publishing—a similar trend was evident in academic publications. By 2020, the phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ was used 20 times more often than a decade earlier.

The reverse phrase ‘migrants and refugees’ has seen a similar rise in usage and is now more common than ‘refugees and migrants’. (This is not evident from Figure 2, which shows relative frequencies compared to 2012–2014.) The parallel rise of the two phrases shows that the change in usage is not driven by the titles of specific documents or programmes, but by the idea that refugees and migrants are mutually exclusive groups.

Within the IOM there have been divergent attitudes to the defence of an inclusivist definition of migrants in the face of pressure from the much more powerful UNHCR. William Swing, who served as Director-General from 2008 to 2018, unequivocally proclaimed that ‘all refugees are migrants, but not every migrant is a refugee’, an eloquent summary of the inclusivist view.2 His preferred arrangement was to ‘agree to disagree’ with UNHCR, though this was dismissed as an unacceptable compromise by the Refugee Agency, according to people familiar with the exchanges.

Even under Swing's leadership, IOM's communications staff gave in to pressure from UNHCR and undermined the IOM's own position. The campaign ‘i am a migrant’ sought to counter negative stereotypes by inviting individual migrants to share their story and take pride in being migrants (de Jong & Dannecker, 2017). However, the inclusion of refugees among the diverse migrants angered UNHCR. In response, IOM republished the stories of self-proclaimed migrants (without consulting the individuals concerned) as ‘i am a refugee’ (Carling, 2016).

In 2018, the Director-General position was taken over by António Vitorino. Under his leadership, the meaning of migrants has been further obscured. Vitorino stated in a meeting on migration data that he does not have an opinion on whether ‘migrants’ include refugees.3 And when a new edition of the IOM's Glossary on Migration was published in 2019, it was after a six-month consultation process that resulted in an ambiguous definition of migrants that—unlike the previous edition and the draft text – skirts the issue of whether ‘migrants’ is understood to include refugees (IOM, 2019). Adherence to the inclusivist definition is made explicit in a note, but conspicuously absent from the definition itself.

In response to a request for clarification, Mr Vitorino, through a spokesperson, neither confirmed nor denied that there has been a change in policy.4 He asserted that the IOM's current definition ‘is intended to account for drivers of forced migration’ but also stressed that the 2019 definition—which leaves out any mention of forced migration or refugees—was updated ‘to reflect recent developments’.

Mr Vitorino's statement stopped short of echoing Swing in saying that ‘refugees are migrants’. Instead, he acknowledged that ‘refugees are persons on the move crossing borders’. While Mr. Vitorino thus sustained ambiguity around the meaning of ‘migrants’ one part of his statement was crystal-clear, even rendered in bold font: a UNHCR-appeasing reassurance that the IOM's definition ‘is without prejudice to the protection regimes [for] refugees’.

As Mr Vitorino's first five-year term is ending, he is challenged by one of his deputies, Ms Amy Pope, who has been launched as a candidate to take over as Director-General. While her instatement would return IOM's to the tradition of being US-led, it might not bring back the principled clarity of William Swing on the meaning of ‘migrants’. In her response to a request for clarification of her position, she did not confirm commitment to an inclusivist definition.5 Instead, she stressed that ‘IOM's primary mission is to support people on the move who are not protected by the [Refugee] Convention’. This interpretation is not reflected in the IOM's mission statement6 but resonates with a self-consciously non-threatening relationship with UNHCR. It also fits well with UNHCR's understanding of ‘migrants’ to adopt a residual mission for a residual group of people on the move.

IOM and UNHCR have complementary competencies and need to find a workable division of labour. But it is distressing that organizational sensitivities and turf battles are tackled by sacrificing the meaning and clarity of analytical terms that matter to our shared knowledge and the people crossing borders.

- Instead of ‘refugees and migrants’, say ‘refugees and other migrants’.

- Instead of ‘migrants and refugees’ say ‘migrants, including refugees’.

- And remember that ‘migrants’ on its own can refer to people with and without the right to protection as refugees.

Endnotes

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The source data for Figure 2 are openly available in Zenodo at http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7761798.