Maintenance exercises for urinary continence after rehabilitation following radical prostatectomy: Follow-up study

Abstract

In a previous paper, we presented a complete pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) program; follow-up data and maintenance exercises for such program have yet to be studied. The role of PFMT for urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy is known in literature; the rehabilitation program should be tailored to the patient's needs, and should include maintenance exercises upon completion of the rehabilitation program. The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of a maintenance programme of PFMT on urinary incontinence. After rehabilitation with PFMT, described in previous papers, patients with urinary leakages after radical retropubic prostatectomy followed the maintenance program described in this paper in a prospective study. Leakages were assessed after 3, 6, 12 and 18 months from rehabilitation. Two hundred and seventy-three patients were included; 216 (79.1%) achieved continence at the end of the rehabilitation programme described in the previous paper; the 57 who remained incontinent were significantly older (66 vs. 71 years, p < 0.001). Continence was maintained in 78.7%, 77.3%, 76.9% and 74.4% of the patients surveyed at 3, 6, 12 and 18 months respectively. The maintenance program proposed in this paper illustrates in detail the body positions, the number of contractions and the moments of the day in which the exercises should be performed. The long-term effects data support the efficacy of this program.

Highlights

- Pelvic floor muscle training is an effective method for treating urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy.

- In a previous paper, we have shown the efficacy of a complete series of exercises.

- This paper presents the maintenance programme dedicated at supporting continence in the long run, up to 18 months.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC?

Pelvic floor muscle training after radical prostatectomy has a well-established role. In previous works, we presented a PFMT program which proved useful.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS?

The maintenance program presented in this paper gives satisfactory results in the long run, even in patients starting rehabilitation more than 12 months from surgery. Future studies shall concentrate on the qualitative aspects of the nurse–patient supportive relationship, which appears fundamental during both rehabilitation and follow-up.

1 RATIONALE

Urinary incontinence is defined as any involuntary leakage of urine.1 Prevalence ranges from 2% to 60%, with radical prostatectomy being one of the main causes.2 Radical retropubic prostatectomy is the most common surgical operation for removing prostate-limited cancer. It consists in removing the prostate and the seminal vesicles through a retropubic, laparotomic approach.3 Many anatomic structures are involved in urinary continence, including the urethral sphincter, levator ani muscle, puboprostatic ligaments, bladder neck, endopelvic fascia, and the neurovascular bundle.4 In particular, during radical prostatectomy the risk of damaging the external sphincter and its nervous terminations is high, with frequent consequences in terms of urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.2, 5

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is one of the possible conservative treatments for urine leakages, and consists in selective contractions of the levator ani muscle.6 During contractions, muscular fibres can occlude the distal urethra in correspondence of the hiatus urogenitalis, thus limiting or eliminating involuntary leakages. In order to achieve such result, the patient must gain self-awareness of pelvic muscles, develop muscular hypertrophy (because pelvic muscles need to guarantee their physiological performance and to carry out a part of the urethral closure work usually done by the external sphincter) and to develop the ability to automatically contract the abovementioned muscles in case of sudden increase of intra-abdominal pressure. The goal is to learn the ability to perform and keep the contraction without needing rational thought, to contrast moments of abdominal pressure increasing.2 Learning and automating motor patterns is a complex process, which needs a passage of control from the prefrontal cortex to the subcortical centers, with the simultaneous activation of cerebellum.7

The European guidelines provide a “level A” recommendation for PFMT1 and various other papers support structured rehabilitation programs, some of which suggesting even preoperative exercise8, 9 or advanced exercises in combination with techniques such as Pilates.10 In many investigations regarding PFMT, only the number of repetitions is specified, without any information on the positions to be adopted by patients, which is crucial because it influences the difficulty of the exercise. Exceptions include the work by Dorey et al.11 in which a pelvic floor muscle regimen for treating urinary incontinence after prostatectomy is presented. However, some patients are often unable to perform the exercises in some body positions (i.e. due to joint diseases) and many find it difficult to isolate the contraction of the levator ani from other muscles, such as adductors and abdominals. For these reasons, it is important to follow scientific principles, but also to tailor the exercises to the patient's features.12 Furthermore, other authors have proposed detailed programs of physically intense exercises based on sport skills and multimodal interventions13 but such interventions, although effective, may be difficult to implement in outpatients services like those commonly found in urology departments.

In a previous study,14 we presented a complete program of progressive PFMT exercises, with results on 122 patients. The program shared the scientific principles available in literature: the therapists were specialized nurses, assessment of pelvic floor muscle strength was performed by a digital anal examination with the pubococcygeal test15 and the three basic positions for pelvic exercises suggested by Dorey et al.11 were adopted (lying, sitting and standing). Fluid advice and written instructional material were also provided. However, in addition to those principles, our program requested patients to train both fast-twitch and slow-twitch fibres, through different criteria of contraction, as suggested by other authors.16 We sought to make exercise progressively more difficult and intense, as suggested by the literature and accordingly to muscular training physiology.13 The program requested patients to perform exercises in sedentary and walking postures.17 Finally, a position dedicated to inhibiting contraction of adductor muscles (a frequent problem in our population of patients) was included in the program. The program gave good results: 90 patients out of 122 (73.7%) achieved rehabilitation after a median of 6 PFMT sessions interquartile range (IQR) [5;8] (), reaching daily urine leakages to less than 10 g and starting from a median of leakages of 150 g/day IQR [90;300]. The remaining patients who did not reach the result, reached anyway clinically and statistically significant results with final leakages of 90 g/day, IQR [90;157], p < 0.001; starting from leakages of 540 g/day, IQR [300;840]. Compared to patients who refused rehabilitation, this rehabilitation program showed statistically significant improvement of patients' ability to hold urine (p < 0.0001).

Although these data support the efficacy of our rehabilitation program, it is necessary to evaluate the long-term effects, because continuing exercises is necessary after rehabilitation to maintain continence, as confirmed by the literature.13, 18

2 AIMS OF THE PROJECT

This paper presents the long-term results of the abovementioned PFMT program, with follow-up after 3, 6, 12 and 18 months from the end of rehabilitation, on a sample of patients with urinary incontinence after radical retropubic prostatectomy.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Sample

A prospective study was performed on a sample of consecutive patients with stress urinary incontinence after radical retropubic prostatectomy, in the urology outpatients service of a teaching hospital in Milan. Those undergoing radiotherapy in the period considered for rehabilitation were excluded.

3.2 Data collection methods

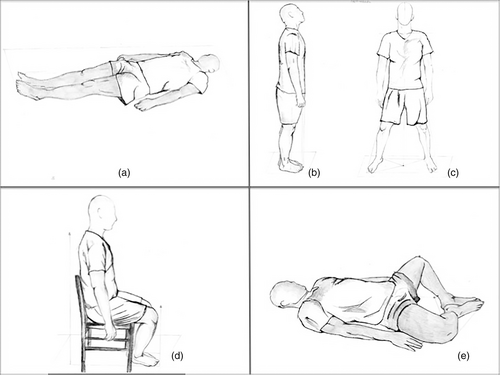

We asked patients to quantify daily urine leakages through 24 h pad-test as suggested by the literature19 during both rehabilitation and follow-up. All patients followed a PFMT program presented in a previous work14 and summarized in Table 1.

| Number | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Morning | The patient should be instructed to palpate his nucleus fibrosus by touching the middle perineum (just behind the scrotus). He should be taught to perceive the movement of the nucleus under his finger, as an indicator of correct performance. A basic exercise, facilitated by the supine position which prevents the pelvic organs from compressing the bladder with their weight. |

| Part 1: supine, stretched legs (Figure 1a) | ||

| a) Fasta contraction and fast release, 10 times | ||

| b) Rest for 2 min | ||

| c) Repeat point (a) | ||

| Part 2: repeat points a, b and c, with bent knees | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| Part 1: supine, stretched legs (Figure 1a) | ||

| a) Fast contraction, maintain for 5 s, release as slowly as possible. Perform 10 times | ||

| b) Rest for 2 min | ||

| c) Repeat point (a) | ||

| Part 2: repeat points a, b and c, with bent knees | ||

| 2 | Morning (Figure 1b) | Slightly more difficult than exercise 1, due to the action of gravity. When the exercise is performed correctly, the patient should find it more difficult with his legs spread (the position with legs closed ensures additional sustain to the pelvic organs, with better contrast to gravity). If the patients contract his gluteal muscles (unnecessary for rehabilitation) he can be instructed to lean against a wall: this will make the gluteal contraction evident, because the patient will be pushed forward |

| Part 1: standing, legs closed, same contractions as for exercise 1 (morning) | ||

| Part 2: standing, legs spread, same contractions as for exercise 1 (morning) | ||

| Afternoon (Figure 1c) | ||

| Part 1: standing, legs closed, same contractions as for exercise 1 (afternoon) | ||

| Part 2: standing, legs spread, same contractions as for exercise 1 (afternoon) | ||

| 3 | Once a day (Figure 1d) | The patient needs to learn this exercise in real life settings, for example every time he sits/stands during his daily activities, in order to use it for preventing leakages in common situations at risk of sudden increase of intra-abdominal pressure |

| a) Sitting on a chair: perform contraction while seated, and maintain it while standing up. Release as slow as possible when the upright position has been reached | ||

| b) Perform contraction and maintain it while sitting down. Release as slow as possible once seated | ||

| c) Repeat the first two points (10 times) | ||

| 4 | Morning (Figure 1e) | This exercise can be useful when the patient tends to use his abductor muscles, which are unnecessary for rehabilitation. This body position prevents him from contracting such muscles, thus improving the ability to isolate the contraction of the levator ani. A pillow can be placed under each knee, to avoid excessive muscle stretching |

| Supine, with bent knees, feet together (form a rhombus with the legs). Fast contraction, release as slow as possible, perform 20 times | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| Supine, with bent knees, feet together (form a rhombus with the legs). Fast contraction, maintain for 5 s, release as slow as possible. Perform 20 times | ||

| 5 | Morning | Advanced exercise. Gravity, vibrations caused by walking, and continuous changes in the position of the force vectors inside the pelvic floor, cause pelvic muscles to continuously adapt their tone. Additional difficulty can be added by asking the patient to cough during the exercise (requires very compliant patients) |

| a) While walking, perform rapid contraction and release quickly. Repeat 10 times | ||

| b) Rest for 2 min | ||

| c) Repeat point (a) | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| a) While walking, perform rapid contraction; maintain it for 5 s, then release as slowly as possible. Repeat 10 times | ||

| b) Rest for 2 min | ||

| c) Repeat point (a) |

- a “Fast” = as fast as the patient can.

Rehabilitation was defined as less than 10 g of urine loss per day.20 During each session, patients received a brochure with written explanations and pictures of every single exercise suggested by the nurse. Figure 1 reproduces the pictures on the brochure.

The number of patients has increased since the publication of the original work, and the follow-up data presented in this study are based on the number of patients currently under treatment; for this reason, we chose to give a summary of the updated results.

3.3 Characteristics of the maintenance program

At the end of the treatment period, according to the literature16 maintenance exercise were assigned to the patients, in order to help them maintaining the results. Very few indications exist in literature, about the difference that arguably should exist between rehabilitation and maintenance exercises: the first ones need to be practiced daily and are also aimed at strengthening muscles, and therefore should reasonably be more intense than maintenance. According to this principle, we created a maintenance program with exercises similar to those used for rehabilitation, but with less intensity. The maintenance program consisting in the following exercise: sitting on a chair, feet laying on a 20 cm mount, with legs spread, the patient had to perform a contraction, maintain it for 3/5 s, then release. The patients repeated this exercise for five consecutive minutes, twice per week. After achieving rehabilitation, some patients can have relapses of incontinence, mainly due to the fact of interrupting the maintenance scheme. In such a situation, specific exercises are needed, to quickly recover continence. Since several types of incontinence exist, we created different exercises for relapses (Table 2). As happened for the rehabilitation program, the nurses explained all maintenance exercises, and patients received a leaflet with written instructions and figures for each exercise.

| Numbers | Type of incontinence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stress incontinence Leakages after cough, sneeze, weight lifting, standing up from a chair or bed |

Morning |

| a) Sitting on a chair: perform contraction while seated, and maintain it while standing up. Release as slow as possible when the upright position has been reached | ||

| b) Perform contraction and maintain it while sitting down. Release as slow as possible once seated | ||

| c) Repeat the first two points 20 times (one time a day for 7 days) | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| a) Supine, with bent knees, feet together (form a rhombus with the legs). Fast contraction, release as slow as possible | ||

| b) Perform 20 times. (One time a day for 7 days) | ||

| Note: Remember to contract pelvic muscles every time you standing up | ||

| 2 | Dribbling incontinence Urine drops leakages while walking |

Morning |

| a) Supine, with bent knees, feet together (form a rhombus with the legs). Fast contraction, release as slow as possible. | ||

| b) Perform 20 times. (One time a day for 10 days) | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| Part 1: standing, legs closed | ||

| a) Fast contraction, maintain for 5 s, release as slowly as possible | ||

| b) Rest for 10 s | ||

| c) Repeat point (a) 20 times | ||

| Part 2: standing, legs spread, same contractions as for part 1 (between the performance of parte 1 and 2 rest for 2 min. One time a day for 10 days) | ||

| Note: Remember to contract pelvic muscles when you walking or climbing ladders | ||

| 3 | Stress incontinence Urine leakages when the bladder is full (often after normal movement) |

Morning |

| a) Supine, with bent knees, feet together (form a rhombus with the legs). Fast contraction, release as slow as possible | ||

| b) Perform 20 times (one time a day for 10 days) | ||

| Afternoon | ||

| Part 1: standing, legs closed | ||

| a) Fast contraction, maintain for 5 s, release as slowly as possible | ||

| b) Rest for 10 s | ||

| c) Repeat point (a) 20 times | ||

| Part 2: standing, legs spread, same contractions as for part 1 (between the performance of parte 1 and 2 rest for 2 min. One time a day for 10 days) | ||

| Note: Remember to urinate every 2–3 h during the day. A regular urination allows to feel the stimulus when is reached a correct maximum urine volume (250 ml) |

A schedule of follow-up session was prepared for each patient, with consultations with the nurse after 3, 6, 12 and 18 months from the end of the rehabilitation program. After the first 30 days, between two consecutive consultations, telephone contact was used to verify the situation of patients; they could access the outpatients at any moment in case of relapse or problems. As happened for the rehabilitation program, specialist nurses taught all exercises and verified that patients performed them correctly; this happened at every follow-up consultation in the outpatients.

3.4 Data analysis

Data normality was assessed with Kolmogorov–Smirnov's test. ANCOVA for repeated measures was used to assess the role of age, body mass index (BMI), and late rehabilitation (having started the program after more than 12 months) on urine leakages. Blom's transformation was used for obtaining normal distribution where needed, and goodness-of-fit was assessed by calculating the R2 coefficient. Significance level was set at 0.05 for all analyses. All calculations were performed with SAS ® 9 (SAS Inc.).

3.5 Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Italian law on data protection; ethical approval had already been sought for the study protocol of the previous investigation, which included the follow-up assessment reported in this paper. Informed consent was obtained by all participants.

4 RESULTS

Two hundred and seventy-three consecutive patients with stress urinary incontinence were enrolled, aged 69.2 ± 4.3, mean BMI 25.5 ± 3.2, and started following the rehabilitation program described Table 1. The sample includes the 122 patients enrolled in the original study, plus others who have undergone surgery and have been enrolled in the following years. Sixteen patients did not achieve clinically significant results after a median of 5 PFMT sessions, IQR [4;8] and decided to quit. Their median urine leakages before PFMT were 790 g/day, IQR [450;1450]. Other 41 did not reach continence at the end of the programme. Patients who did not achieve continence were significantly older than the others. The characteristics of the sample are described in Table 3; data regarding leakages are presented as median and interquartile range (Kolmogorov–Smirnov's test: p = 0.01).

| Variable | Rehabilitated | Not rehabilitated | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who finished the rehabilitation program | 216 | 57a | – |

| Patients starting PFMT after >12 months from surgery | 18 | 4 | 0.99b |

| Mean age (years) | 66.2 ± 4.3 | 71.1 ± 1.6 | 0.01 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 3.2 | 24.9 ± 3.1 | 0.074 |

| Median leakages before rehabilitation | 160, IQR = [110;300] | 520, IQR = [320;1450] | <0.001 |

| Median number of PFMT sessions | 7, IQR= [5, 10] | 7, IQR = [5;11] | 0.09 |

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

- a 16 patients dropped out during the study.

- b Fisher's exact test.

Urine leakages showed clinical and statistical differences between rehabilitated and non-rehabilitated patients. Although those who could reach the continence had greater leakages, they were able to reduce their median of leakages from 520 to 80 g/day. This improvement was clinically and statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Twenty-two patients started PFMT program after 12 months or more from the surgery, with baseline median leakages of 290 g/day, IQR [90;450]. Four of them did not achieve continence, while 18 reduced their urine loss from 160 g/day, IQR [110;300], to 10 g/day, IQR [0;90] (p < 0.001). Table 4 illustrates the median leakages at the end of the PFMT program and during the follow-up (3, 6, 12, and 18 months).

| Period | Rehabilitated | Leakages (rehabilitated) | Not rehabilitated | Leakages (not rehabilitated) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End rehabilitation | 216 (79.1%) | Me = 0, IQR [0;10] | 57 (20.9%) | 100 [70;170] | 273 |

| 3 months | 215 (78.7%) | 0 [0;10] | 58 (21.3%) | 100 [70;170] | 273 |

| 6 months | 211 (77.3%) | 0 [0;0] | 62 (22.7%) | 100 [70;180] | 273 |

| 12 months | 210 (76.9%) | 0 [0;0] | 63 (23.1%) | 110 [70;150] | 273 |

| 18 months | 203(74.4%) | 0 [0;0] | 41(25.6%) | 110 [70;150] | 244a |

- a 29 patients lost at follow-up.

No statistically or clinically significant differences were found between the steps of the follow-up process (end of rehabilitation-3 months p = 0.41; 3–6 months p = 0.37; 6–12 months p = 0.65; 12–18 months p = 0.34). Age, BMI, and having started rehabilitation after more than 12 months from surgery did not affect the results (ANCOVA: p = 0.20, p = 0.12 and p = 0.08 respectively, R2 = 0.84).

During the first 3 months after rehabilitation, the p-value was borderline (0.055), indicating small variations in patients' leakages. 18 patients had relapses of incontinence after the end of rehabilitation, because they interrupted their maintenance exercises, but were able to regain continence by following the recovery program showed in Table 2.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of the study show the long-term efficacy of our PFMT program: 79.1% of patients reached continence at the end of the rehabilitation period and after 18 months, the rate of continent patients was still high (74.4%). Of note, even those who did not reach the 10 g goal obtained clinically significant improvements in terms of leakages.

As an implication for practice, the maintenance exercises complies with the indications provided by the literature11, 15 and together with the rehabilitation PFMT investigated in a previous study14 provide a complete program for treating urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Some authors16 point out that continence can be spontaneously recovered by some patients over the first year after surgery; however, the European guidelines (Nambiar et al.)1 point out that PFMT speeds up recovery especially in the first months, as confirmed by our previous study.14

In order to correctly perform the exercises, it is fundamental that patients learn how to perceive muscular contraction, the movement of nucleus fibrosus, weight distribution, breath, fatigue and pain. Antagonist synergies (e.g. contraction of the abdominal wall while performing contractions) need to be excluded from the exercises; this is often difficult for patients without help from nurses. Repetition and adherence to the program were considered as two fundamental characteristics of the program, as pointed out by relevant literature.21 Patients with urinary incontinence can experience impaired quality of life and uncertainty during the rehabilitation period, because regaining continence is sometimes a long process, requiring the person to actively participate by performing exercises every day. Finally, the rehabilitation process can experience relapse of incontinence; due to all these variables, the pathway towards continence can be sometimes cumbersome and frustrating. Sound clinical judgement is therefore a fundamental requirement for nurses to choose the appropriate exercises, according to the physical capabilities of patients; rehabilitation nurses must provide continuous support, monitoring, teamwork and assessment, in order to help patients reaching their goals. For this reason, studies regarding characteristics of the nurse–patient therapeutic relationship would be of interest to explore the relational aspects that foster patients' compliance and support their commitment to the programme.

A limitation of this study is the non-randomized sampling strategy, which might have introduced some biases, especially as regards the ability of patients to maintain adherence to the programme. The literature22 indeed suggests that convenience sampling might lead to involuntarily select persons with specific cognitive and/or educational characteristics. These might have influenced the abovementioned relational aspects, as well as patients' ability to understand and correctly learn the exercises. Future studies could mitigate this bias by using randomization.

Even though the problem of urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy has been known for a long time, even in recent years many studies have been published on conservative rehabilitation. Some authors have conducted clinical trials,23, 24 others have presented a systematic review of the literature.25 Some of these studies24 reflect the technical advancement of surgical procedures and suggest that there is still a need for investigations in the field of conservative management of incontinence after prostatectomy. Finally, in a recent meta-analysis26 that has analysed the association between PFMT, electrical stimulation and biofeedback, the efficacy of these treatments combined has proven superior to that of PMFT alone. Data regarding long-term effects of these combinations is lacking in literature; in the rehabilitation clinics in which our study took place, electrical stimulation has been used for years with good results.27 It would be interesting to conduct a future comparison between the findings of the present study and the long-term outcomes of this PFMT programme combined with electrical stimulation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. [Correction added on 23 May 2022, after first online publication: CRUI-CARE funding statement has been added.]