Porokeratoses: an update on pathogenesis and treatment

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding source: None.

Abstract

Porokeratoses (PK) are a group of uncommon dermatoses characterized by abnormal epidermal differentiation due to a disorder of the mevalonate metabolic pathway. Several clinical subtypes exist that can be associated with the same patient or affect different patients within a family and could, therefore, be different expressions of one disease. All PK subtypes share a common histopathologic finding, the cornoid lamella, a vertical stack of parakeratotic corneocytes embedded in an orthokeratotic horny layer. PK often affects immunosuppressed patients, in whom the course may parallel the level of immunosuppression. The pathogenesis of PK, which had long remained mysterious, has been recently unraveled after discovering pathogenic variants of genes involved in the mevalonate metabolic pathway. The disease is due to germline pathogenic variants of genes of this pathway but requires a second-hit event to manifest; therefore, PK is considered a dominantly inherited but recessively expressed condition. The prognosis of PK is usually favorable, even though the lesions progress to keratinocyte carcinomas in 7%–16% of patients. The treatment of PK was based on physical (ablative) procedures and various (topical or systemic) treatments, whose efficacy is nevertheless inconsistent and often temporary. The discovery of the metabolic pathway involved in the pathogenesis of PK paved the way for the elaboration of new topical treatments (combination of statins and cholesterol), which are more regularly efficacious compared with older treatments, even though the management of some patients with PK may still be challenging.

Introduction

Porokeratoses (PK) are a group of relatively uncommon, clinically and genetically heterogeneous dermatoses characterized by trouble with epidermal keratinization due to pathogenic variants of genes involved in the mevalonate metabolic pathway. They manifest clinically with well-limited plaques with a keratotic border and histologically with the so-called cornoid lamella (CL), a vertical stack of parakeratotic corneocytes embedded within the neighboring orthokeratotic horny layer. The term “porokeratosis” (from the Greek “πορος”: pore and “κερατωσις”: keratosis) proposed by Mibelli in 1893 is not accurate, as the origin of the disorder is not limited to adnexal (sweat of hair-follicle) pores. The treatment of PK often remains challenging despite the recent emergence of promising topical treatments targeting the metabolic pathway responsible for the disease.

Clinical features

The primary lesion of PK is a dry, brownish, keratotic, asymptomatic papule of a few mm, which slowly spreads peripherally to form, after several weeks or months, a well-limited plaque of variable size and shape. The edge of the plaque corresponds to a “roundabout” groove from which a horny blade emerges, pointing toward the center of the plaque. The center of the plaque is slightly atrophic and depressed. It is occasionally slightly pigmented and is rarely hyperkeratotic. Localized and generalized subtypes of PK exist, and they are distinguished according to clinical aspects, such as the size, number, location, and arrangement of the lesions.1, 2

Porokeratosis of Mibelli

This saccounts for over one-third of all PK cases. It shows a male predominance and manifests clinically with one or a few large annular or polycyclic plaques, which are usually unilateral (Figure 1), more rarely bilateral and/or symmetric.3 The center of the plaques is atrophic but may be hyperkeratotic. The lesions are usually asymptomatic but may be pruritic, particularly within the folds. Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PKM) may be sporadic or familial, inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern; in the latter case, the disease usually starts in childhood. However, PKM may appear in adulthood.

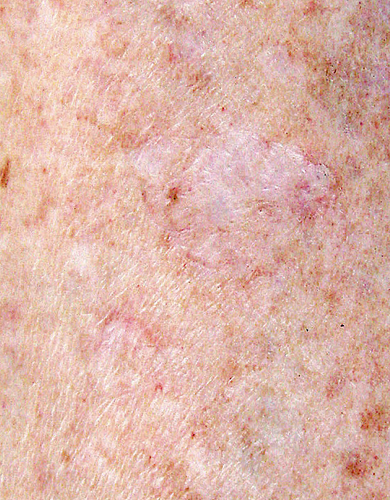

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis

This is the most common subtype, primarily encountered in countries with high levels of sunshine. The lesions usually appear during the third or fourth decade of life with a slight female predominance.1, 4 Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAPK) manifests with numerous (sometimes >100) small annular lesions (ca. 1 cm), appearing bilaterally and symmetrically on sun-exposed body areas, such as the dorsal legs and forearms (Figure 2). The lesions tend to worsen after exposure to sunlight5 or to artificial sources of ultraviolet (UV) light A or B6-9 and are less conspicuous in winter. They are pruritic in one-third of the patients.

Disseminated superficial porokeratosis

This is clinically very similar to DSAPK but appears earlier in life (sometimes at birth) and is not influenced by UV radiation; accordingly, the lesions do not predominate on sun-exposed areas and affect the trunk, genitalia, or the palmoplantar surfaces equally. Oral localizations have been reported.10

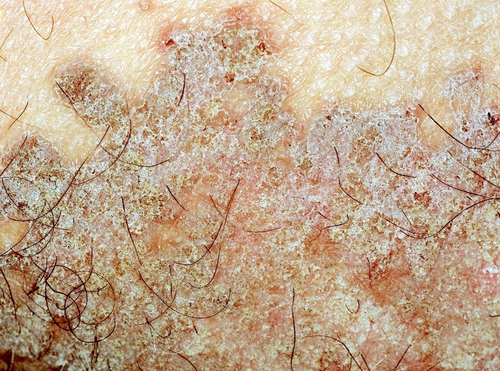

Linear porokeratosis

This relatively rare PK subtype is characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques arranged in a linear, zosteriform pattern (Figure 3). It appears early in life, sometimes at birth, and has been reported in association with DSAPK.11

Punctate palmoplantar porokeratosis

This form is also known as ‘hereditary palmoplantar punctate keratoderma type II’ (MIM 175860). It manifests with multiple 1–2 mm punctate lesions resembling “music-box spicules” that appear initially on the palms and then the soles.12 They may be sensitive to pressure. Punctate palmoplantar porokeratosis (PPPK) may be associated with PKM or linear porokeratosis (LPK).

Disseminated palmoplantar porokeratosis

This form manifests with 1–2 mm bilateral and symmetrical, red-brown keratotic papules, which appear during adolescence or adulthood, preferentially in males. Even though sporadic forms exist,13 the majority of cases are familial. Disseminated palmoplantar porokeratosis (DPPPK) may be an initial presentation of disseminated superficial porokeratosis (DSPK).

Other rarer clinical varieties of PK have been described. They include PK of the folds (or genitogluteal or “ptychotropica” or penoscrotal PK)14 (Figure 4); eruptive (papular-pruritic) PK15; nodular prurigo-like PK16; ulcerative PK17; bullous eruptive PK18; pustular PK; hyperkeratotic-verrucous PK19; isolated genital PK20; follicular PK21; and reticulated PK.22 ‘Porokeratoma’ is a more recently described lesion usually manifesting as a keratotic papule (Figure 5) containing multiple CL; it seems to represent a localized, sporadic form of PK and can rarely be associated with PKM.23

Of note, the existence of families presenting more than one PK subtype among its members and of patients presenting with more than one PK subtype suggests that the distinction among the various PK forms may be purely morphological.

Noninvasive imaging techniques can facilitate the diagnosis of PK. The dermatoscopic hallmark of PK is a keratin rim (corresponding to the CL), observed in >92% of the lesions. Dotted or glomerular vessels are present in the center of the plaques in almost half of them. Other relatively frequent dermatoscopic findings include nonperipheral scales, gray-brown dots or pigmentation along the keratin rim, and light-brown pigmentation within the keratin rim.24 The peripheral keratotic rim of the lesions can be better visualized with UV light dermatoscopy.1, 25 In vivo confocal microscopy visualizes the CL as a clear structure containing nuclei (parakeratosis); it shows disorganization of the underlying epidermis and an absence of the granular layer.26 The CL can also be visualized by optical coherence tomography.27

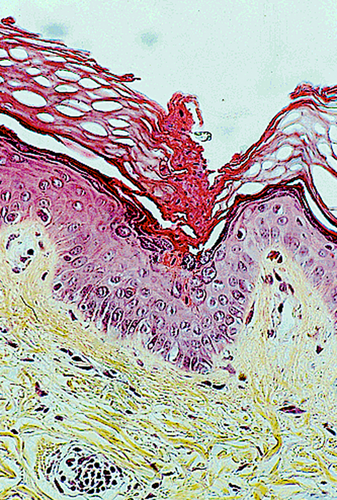

Histopathologic features

The characteristic histologic feature of PK is seen in the peripheral keratotic margin of the lesions: it consists of a narrow vertical column of parakeratotic corneocytes resembling ‘a stack of plates’, called 'cornoid lamella' (CL); this is embedded within a thickened, orthokeratotic horny layer. The CL is seated on a shallow depression of the underlying epidermis; at this level, the granular layer is absent, and the underlying stratum spinosum contains occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes. The corresponding basal cell layer keratinocytes may be vacuolized (Figure 6). The CL is sometimes found within a hair follicle or a sweat gland pore, but this phenomenon seems to be fortuitous. The upper dermis contains a moderately dense inflammatory infiltrate consisting mainly of activated T lymphocytes (including FoxP3+ regulatory lymphocytes),28 which sometimes abut the basal cell layer. Eosinophils are rarely present. The papillary dermis seldom contains colloid bodies or amyloid deposits of keratinocyte origin.29 The central part of the plaque usually shows mild orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and a slightly atrophic stratum spinosum. In DSAPK, the dermal infiltrate may be denser, with a lichenoid pattern. Epidermal necrosis, ulceration, and subepidermal detachment are rarely observed. The histological changes are more pronounced in PKM (the CL is less conspicuous in other PK subtypes). The lesions of PK associated with immunosuppression do not have distinguishing features.30

On electron microscopy, CL corneocytes contain pyknotic nuclei, degraded organelles, and lipid droplets. Underneath the CL, keratohyalin granules and lamellar bodies are diminished. Dyskeratotic keratinocytes show degenerative features (perinuclear vacuoles, dense tonofilaments).30 Filaggrin expression is decreased, in line with the reduction of the granular layer thickness, and involucrin expression is increased.31-34 Epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) are quantitatively decreased compared to dermal LCs.28, 34

The histological appearance of PK is characteristic and confirms the diagnosis, provided that the biopsy sample is taken from the keratotic border of the lesion where the CL is present. It should be remembered, however, that the CL is not specific to PK since it has been observed in various other unrelated conditions, such as actinic keratoses, basal and squamous cell carcinomas, seborrheic keratoses, and warts.35

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of PK remained mysterious for several decades. The disease was believed to be due to the centrifugal spread of a clone of abnormal, mutated epidermal keratinocytes located at the base of the CL.36 In 2012, it was discovered that the various forms of PK are due to a disorder in the mevalonate metabolic pathway caused by pathogenic variants of genes involved in this pathway. These variants are identified in the vast majority of familial (98%) and the majority of sporadic (73%) PK cases37; they involve loss-of-function variants of genes encoding for the enzyme mevalonate kinase (MVK) and for other enzymes downstream of MVK in this pathway, namely mevalonate diphosphodecarboxylase, phosphomevalonate kinase, and farnesyl-diphosphate synthase. Several data suggest that a second, acquired/postnatal genetic alteration of the wild type in the mevalonate pathway genes is required for PK lesions to develop (according to Knudson's “two-hit” hypothesis); this second genetic event would transform the native heterozygous genotype into a biallelic mutated genotype in the affected cells. PK would, therefore, be dominantly inherited but recessively expressed following a second post-zygotic somatic, loss-of-function genetic event (such as gene conversion, RNA modification, large deletion, or homologous chromosomal recombination), or following an epigenetic event. The variability of the time of occurrence of this second event could explain the variable age of onset of the various PK forms.38 The disordered mevalonate pathway decreases the end products of this pathway (namely cholesterol) and leads to the the accumulation of toxic metabolites, which induce premature apoptosis of keratinocytes.

Of note, some cases of DSAPK are due to pathogenic variants of the SLC17A9 gene, encoding for transmembrane proteins involved in the transport of small molecules.39 Furthermore, in some PK cases, no pathogenic gene variants can be found, probably because the patients harbor variants of unknown genes or because of other nonclassical or mosaic/somatic events that are undetectable by the currently available mutation screening methods.39

- UV radiation (from sun exposure, PUVA- or UVB therapy): its essential role in the development of DSAPK is supported by clinical-epidemiological data and has been demonstrated experimentally.7 Electron-beam therapy and ionizing radiation may also act as triggering factors.40

- Drugs: the most frequently incriminated agents include biotherapies (anti-TNFa, trastuzumab) and hydroxyurea; prednisone, diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, furosemide), antibiotics (flucloxacillin, gentamicin), temozolomide, suramin, benzene, and immune-checkpoint inhibitors have also been incriminated.40-42 These drug-induced PK cases usually manifest as DS(A)PK (60%), disseminated eruptive PK, genital PK, and PKM.41

On the other hand, many cases of PK appear in immunocompromised patients, including those with organ transplantation, lymphomas, HIV infection, and various inflammatory or autoimmune diseases treated with immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents.43 An evolutionary parallelism of the lesions with the level of immunosuppression is occasionally noted, as the lesions may regress entirely upon discontinuing the immunosuppressive treatment.44 How immunosuppression favors the development of PK is not precisely known; a role of the immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs as a ‘second hit’ event acting on the background of an existing pathogenic variant of the genes involved in the mevalonate pathway is possible.41

Course Prognosis

The natural course of PK is progressive, although slow, and worsens the lesions, manifesting with an increase in their number and size. Spontaneous regression of individual lesions after an inflammatory flare-up occurs rarely. PK in immunosuppressed patients may fluctuate in parallel with the level of immunosuppression.44

PK lesions may undergo malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma (4.3-fold increased risk), Bowen's disease, or, more rarely, basal cell carcinoma (2.42-fold increased risk). An increased risk of melanoma (1.83-fold) has also been reported in patients with PK.45, 46 This neoplastic complication develops in 7%–16% of the patients and mainly occurs on long-standing, large lesions of the limbs, as well as in LPK lesions. The carcinomas are multiple in one-third of these cases and can, although rarely, cause lymph node metastases and death.47 PK is, therefore, often considered a premalignant dermatosis.

Treatment

The treatment of PK is often motivated by the aesthetic burden of the lesions and is justified by the risk of malignant transformation. Unfortunately, no extensive, controlled studies on the treatment of PK exist.48 Several treatment options have been tried with variable results. The previously applied treatments do not guarantee a complete and/or lasting lesion cure. New topical treatments were proposed recently after discovering the metabolic pathway involved in PK (Table 1). They are very promising, although not consistently effective.49, 50

| Medications | Physical |

|---|---|

|

Topical Pathogenesis-directed Combination of 2% statins (lovastatin, simvastatin, or atorvastatin) with cholesterol 2%–5% as cream, lotion or ointment Others Vitamin D derivatives: tacalcitol, maxacalcitol, calcipotriol Imiquimod cream 5% Tacrolimus ointment 5-Fluoro-uracil cream 5% Diclofenac 3% gel Retinoids: tretinoin, tazarotene, adapalene Keratolytics Systemic Oral retinoids: isotretinoin, acitretin, alitretinoin Cyclosporine A JAK inhibitors: tofacitinib, abrocitinib Secukinumab Anakinra |

|

Topical treatments

- Vitamin D derivatives (tacalcitol lotion, calcipotriol cream) have achieved good results in some cases of DSAPK after long-term applications (1.5–19 months).51, 52 However, not all patients are responders. Good results have been obtained in a few patients with the combination of maxacalcitol with cryotherapy53 and calcipotriol with topical corticosteroids (metamethasone).54

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 0.5%–5% cream) applied 1–2 times daily over periods ranging from 3 weeks to several months proved effective in a few PK cases.55, 56 5-FU can be used as a “peel” combined with glycolic acid and applied as a bolus57 or combined with PDT58 and oral retinoids.59

- Imiquimod (5% cream), applied once daily for 3–7 days/week for 1–6 months, has been used successfully in a few patients with PKM, including immunocompromised ones,60, 61 DSAPK,62 LPK,63 DPPPK,64 and PK ptychotropica.65 An inflammatory reaction invariably occurs and can be so intense as to prompt treatment discontinuation. Healing may be followed by sequelae (scarring, hyper- or hypopigmentation). Application of the product under an occlusive dressing improves its efficacy.66 Imiquimod has been used successfully in combination with 5-FU in a patient with PKM67 and in combination with PDT in a patient with PK ptychotropica.68

- Diclofenac 3% gel in hyaluronic acid (1–2 daily applications for 3–13 months) achieved partial remissions in some patients with DSAPK69-71 and genital PK.72 A good result was obtained in one case of DSAPK, with no recurrence after 7 months, and in one case of genital PK (slowing lesion progression and improving subjective symptoms).

- Topical retinoids (tretinoin 0.025%–0.1%, tazarotene, adapalene) have provided modest and inconsistent results.73, 74 Adding calcipotriol (0.005% ointment) to adapalene, 0.1% gel, produced considerable improvement in one case of DSAPK.75

- Tacrolimus 0.1% proved effective in a few patients with PK.76, 77

- Pathogenesis-directed treatments: more recently, targeted topical treatments have been tried to reverse the deleterious effects of the mevalonate pathway deficiency. They consist of a combination of statins (mainly lovastatin, more rarely simvastatin or atorvastatin) 2% with cholesterol 2% (rarely 5%), as cream, ointment, or lotion. The mechanism of action is thought to be the inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, which thereby prevents the accumulation of cytotoxic metabolites (mevalonate) in the cell. Cholesterol is added to reconstitute the end-product of this pathway to maintain cellular integrity and stabilize the extracellular lipid matrix; indeed, low cholesterol levels appear to increase keratinocyte susceptibility to apoptosis and disrupt cell differentiation. The statin component is the critical therapeutic agent, as topical cholesterol alone exerts no significant clinical benefit. The statin/cholesterol combination treatment has been tried for various forms of PK in a few dozen patients, some of whom were refractory to other treatments. The product was applied twice daily for 1.5–6 months.78 It proved effective in the majority of cases49, 50, 79-87 and even achieved some complete cures. This treatment is well tolerated, although one case of contact dermatitis has been reported, leading to treatment discontinuation.88 This combination treatment seems to be less regularly effective in LPK.89, 90 In a randomized study, lovastatin 2% was used as monotherapy in the case of DSAPK, and the results were comparable to those obtained by the combination with cholesterol.86 These results are promising but should be validated by randomized controlled trials.91

Other products that have been used with a variable, usually limited, results include cantharidin 0.7%, ingenol mebutate (currently no longer marketed in Europe), potent dermocorticosteroids, keratolytic products (urea, salicylic acid), or moisturizers aimed at reducing the keratotic surface of the lesions.

Systemic treatments

- Oral retinoids (isotretinoin 20 mg/day, acitretin 0.3–0.5 mg/day, alitretinoin 10–30 mg/day) have been tried in about 15 cases for periods ranging from 1 to 7 months. Their efficacy is variable: good or excellent results have been obtained with acitretin,92-97 which is capable of reducing the thickness of hyperkeratotic lesions, alitretinoin,98 and isotretinoin.59, 90 The effect of retinoids, which regulate keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, appears to be suspensive, as PK lesions often recur after treatment discontinuation. In one case of DPPPK associated with squamous-cell carcinomas, etretinate seemed to inhibit the development of malignant changes.99

-

Cyclosporine A (1–4 mg/kg/day) led to significant improvement in a patient with inflammatory-pruritic PK who had failed to respond to various systemic treatments; however, relapses occurred after the dose was lowered below 1 mg/kg/day.100

-

JAK inhibitors were tried in 2 Chinese patients with pruritic eruptive PK. After 1 month's oral treatment with tofacitinib, a JAK1-3 inhibitor, at a dose of 10 mg/day, pruritus and skin lesions disappeared. The result was maintained 2 months after treatment discontinuation.101 A good result was also obtained in another patient treated for 1 month with abrocitinib (a selective JAK1 inhibitor) at a daily oral dose of 100 mg.102

-

Secukinumab, an IL-17 inhibitor, was given at 75 mg every 3 weeks to a young patient with PKL who had not responded to topical statin/cholesterol cream treatment. After several weeks, improvement was obtained (notably in erythema and hyperkeratosis), which persisted for the duration of the treatment (1.5 years). Tolerance was good.103

- Anakinra (IL-1 inhibitor) was used in a patient carrier of MVK and MEFV mutations with severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) associated with generalized spiculated PK. Daily subcutaneous injections of anakinra (100 mg) significantly reduced the inflammation of HS lesions and improved PK lesions after about 1 month.104

Physical therapies

- Superficial surgical excision with a blade scalpel105 and dermabrasion with a dermatome106 are effective, provided healthy margins are obtained. Excision may be followed by total skin grafting.107 These methods can be applied to patients with few lesions or lesions complicated by a carcinoma.

- Cryotherapy/cryosurgery requires rather long freezing times (20–30 s/cycle) and repeated sessions over the years.48, 108

-

Laser ablation (or vaporization) (erbium YAG, CO2, Q-switched Nd:YAG) provides satisfactory results at the cost of moderate side effects (erythema, hyperpigmentation, edema)22, 109; however, recurrences are possible.110

The combination of CO2 laser and photodynamic therapy, used in two patients, produced mediocre results at the cost of significant side effects (hyperpigmentation, desquamation, and burning sensation).111

- Fractional photothermolysis with the erbium laser produced considerable improvement in lesions and pruritus in two cases of DSAPK.112

- Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with 5-aminolevulinic acid (or its methyl ester) has been tried in small series with modest results (improvement in one-third of cases) and at the cost of side effects (hyperpigmentation, inflammation, erythema, and discomfort).55

- Radiation therapy with Grenz rays (18–24 Gy over 6 weeks) has been successfully used to treat a few patients with DSAPK who had not responded to other treatments, at the cost of transient side effects and frequent recurrences.113

As no controlled studies have compared the various treatment methods of PK, no guidelines exist for treating this condition. Therefore, we believe that the management of patients should be individualized after considering the extent of the lesions (in number and size), their anatomical location, the aesthetic burden, the risk of malignant transformation, and the patient's preference. Considering the benefit-to-risk balance of the available treatments, we suggest that, whenever possible, topical targeted therapies (combination of statins 2%/cholesterol 2% applied twice daily for 2–6 months) should be the first-line therapy. If this treatment is unavailable (or unsuccessful), topical applications of vitamin D derivatives (maxacalcitol, tacalcitol, or calcipotriol), 5% imiquimod of 5-FU cream could be tried. Single PK lesions could be treated with cryotherapy or excised surgically (especially in non-visible body zones). In the case of widespread lesions, retinoids (namely acitretin 0.3–0.5 mg/day for several weeks) could be added to the aforementioned topical treatments.

Concerning prevention, patients with photo-sensitive PK forms (DSAPK) should protect themselves from ionizing radiation (namely sunlight) by sun avoidance and active photoprotection with adequate clothing and sunscreen products. Whenever possible, intake of drugs that can reportedly trigger PK should be avoided. Patients with PK at risk of carcinogenesis should be regularly monitored in order to detect as early as possible any malignant transformation of their PK lesions.

Conclusion

Porokeratoses constitute a group of rare genetically determined dermatoses with diverse clinical presentations and a common histopathologic feature, the CL. Their pathogenesis was unraveled in recent years by discovering pathogenic variants of genes involved in the mevalonate metabolic pathway. This progress paved the way for the elaboration of targeted treatments aimed at reversing the effects of the culprit metabolic disorder. The lesions of PK carry a non-negligible risk of malignant transformation to keratinocyte skin cancers. Therefore, the patients should be treated and regularly monitored to detect and treat these neoplastic complications early.