Full-body skin examination in screening for cutaneous malignancy: a focus on concealed sites and the practices of Australian dermatologists

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding source: Anne E. Cust received a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) investigator grant (number 2008454).

Abstract

Background

Full-body skin examination (FSE) is a vital practice in the diagnosis of cutaneous malignancy. Precisely how FSE should be conducted with respect to concealed site inclusion remains poorly elucidated.

Objective

To establish the approach of Australian dermatologists to concealed site examination (CSE).

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed consisting of an online self-administered 11-question survey delivered to fellows of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Results

There were 237 respondents. Anogenitalia was the least often examined concealed site (4.6%), and 59.9, 32.9, and 14.3% reported always examining the scalp, breasts, and oral mucosa, respectively. Patient concern was the most frequently cited factor prompting examination, while many cited low incidence of pathology and limited chaperone availability as the main barriers to routine examination of these sites.

Conclusion

Most Australian dermatologists do not routinely examine breasts, oral mucosal, or anogenital sites as part of an FSE. Emphasis should be made on identifying individual patient risk factors and education regarding self-examination of sensitive sites. A consensus approach to the conduct of the FSE, including concealed sites, is needed to better delineate clinician responsibilities and address medicolegal implications.

Introduction

Skin cancers are the most frequently diagnosed malignancies in Australia.1 Full-body skin examination (FSE) is the primary method of detecting melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs). FSE involves a head-to-toe examination of the skin, assisted by dermoscopy.2 In Australia, FSEs are usually conducted according to individual risk and preference. There is currently insufficient evidence to support routine population screening for skin cancer, in the absence of hard evidence to suggest mortality benefit.3 However, early skin cancer detection is key to improving prognosis, particularly for melanoma.4, 5

Concealed sites such as the scalp, breast, oral mucosa, and genitalia hold unique significance in the diagnosis of skin cancer. While the incidence of cutaneous malignancy at these sites is low, malignancies at these sites often present at a later stage with resultant poorer prognosis.6-9 A key reason for missed cutaneous malignancy (melanoma and NMSC) at concealed sites is simply omission of inspection.10 In a US study, barriers to dermatologists performing comprehensive routine FSE included practical impediments, such as availability of chaperones, limited time, and fear of professional and sexual misconduct accusations.11 Additionally, some patients avoid seeking FSE due to embarrassment or prefer physicians of a particular gender, while others expect that concealed sites should be routinely surveyed as part of FSEs.12, 13

Despite Australia having the highest rate of skin cancer in the world14 and FSE being an integral part of dermatology practice in Australia, there is no Australian consensus about how the FSE is conducted and sites for inclusion, specifically concealed or sensitive sites. In comparison, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends the entire skin and mucosal membranes be included in FSEs – including the scalp, breasts, oral mucosa, and anogenitalia.15

In Australia, clinicians are expected to operate in a manner that is widely accepted by peers in their field as appropriate practice in the circumstances.16 This requires balancing what may be acceptable to patients as well as what clinicians deem to be clinically appropriate and all-inclusive, or else they may run the risk of potential missed diagnoses and the threat of medical negligence. When guidelines are absent about how to approach the complexities of FSE, clinicians may benefit from a consensus statement to help set clinician responsibilities and patient expectations of care and to address medicolegal implications. The aim of this study was to establish the approach of Australian dermatologists to concealed site examination (CSE), assessing clinician conduct, influencing factors, and barriers to routine inclusion of CSE.

Materials and methods

An online 11-question survey was distributed to fellows of the Australasian College of Dermatologists in 2018 via a weblink as part of the weekly college newsletter (Table S1). The survey was designed using Google Forms and was pre-tested and refined by an expert panel before dissemination. The survey was anonymous, and consent was implied by completion of the survey. Reminder emails were sent 2, 4, and 6 weeks after the initial invitation to participate, and the study closed after 6 weeks.

Demographic data were obtained for clinician respondents' gender and age and the proportion of their total patient cohort that present for FSE. Information regarding the frequency and method, by which respondents examined scalp, breast, oral mucosa, and anogenitalia as part of their FSE, was collected (Table 1). Most survey questions were multiple choice; however, some allowed for free-text response. Information was obtained regarding the issues that respondents thought might arise by not including concealed sites in their FSE and whether they felt that it was the dermatologist's responsibility to examine these sites as part of the FSE.

| Demographic data extracted from Australian dermatologist respondents |

| Gender |

| Age group |

| Percentage of patient cohort presenting for full skin examinations |

| Information provided by respondents |

| Frequency of examining anogenitalia, breasts (in women), oral mucosa, and scalp sites |

| What factors influenced decision to examine or not examine concealed or sensitive sites |

| Practices with which concealed sites were examined |

| Frequency with which a chaperone was recruited |

| Whether respondents perceived concealed site examination was the responsibility of dermatologists versus other health practitioners |

| What factors they perceived would be barriers to patients accepting inclusion of concealed sites in routine full skin examination |

Descriptive statistics for each response were collected using Google Forms. These included the number and proportion of respondents who were male or female and those who were within four pre-specified age brackets (35 or younger, 36–45, 46–55, and 56 or older). Respondents were also asked to estimate what proportion of their total patient cohort, across four quartiles, comprised patients presenting for FSE (25% or below, 26–50%, 51–75%, and 76% or above). Finally, survey responses regarding FSE practices regarding concealed sites were presented as numbers and proportions.

Ethics approval was obtained from St Vincent's Human Research Ethics Committee (2019/ETH 12379).

Results

There were 237 responses from the 516 fellows of the ACD, based on 2018 estimates of practicing Australian dermatologists, representing a 45.9% response rate.16 Of the 237 respondents, 51.9% were male and 38.0% were over 55 years old (Table 2). FSE constituted at least a quarter of all patient presentations for the majority of dermatologists surveyed in our study (85.7%) (Table 2).

| Gender | |

| Male | 123 (51.9%) |

| Female | 114 (48.1%) |

| Age group | |

| 35 years old or younger | 20 (8.4%) |

| 36–45 years | 63 (26.6%) |

| 46–55 years | 64 (27.0%) |

| Older than 55 years | 90 (38.0%) |

| Proportion of total patient cohort that presents for full skin examination | |

| ≤25% | 34 (14.3%) |

| 26–50% | 85 (35.9%) |

| 51–75% | 85 (35.9%) |

| 76–100% | 33 (13.9%) |

The scalp was the most frequently examined concealed site as part of an FSE, with 59.9% of respondents reporting always including the scalp in their routine FSE, followed by the breasts (32.9%) (Figure 1). The oral mucosa was always examined by 14.3% of respondents, while the anogenitalia was described as the least often examined concealed site (4.6%).

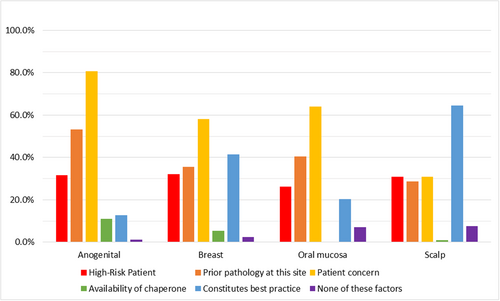

In deciding to examine concealed sites, patient concern about a particular site was the most commonly reported precipitating factor (anogenital 80.6%, oral mucosa 64.1%, and breast 58.2%) except the scalp for which respondents indicated inclusion ‘constitutes best practice’ being the most prevalent response (64.6%) (Figure 2).

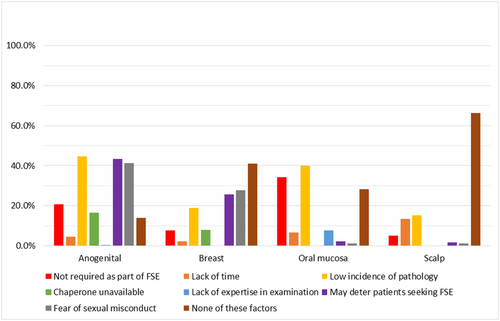

When deciding not to examine concealed sites, respondents most frequently selected the low incidence of pathology for anogenital (44.7%), oral mucosae (40.1%), and scalp (15.2%) as supporting reasons for not including these sites in routine examination, and fear of sexual misconduct was cited as reasoning for examination of the breasts (27.8%) (Figure 3). Free-text responses also indicate some respondents vary their approach based on patient factors, for example routinely examining the scalp in patients with sparse hair coverage as opposed to patients with a full head of hair, due to greater ease of inspecting the scalp.

Australian dermatologists who participated in the survey commonly reported examining the oral mucosa only at patient request (43.0%). Few dermatologists advised patients to seek separate review by a GP or other specialists (i.e. dentists and gynecologists) to assist in the examination of concealed sites (Figure S1). Many respondents reported offering but not necessarily performing an examination of the anogenital region (63.3%) and breasts (44.7%), guided by patient response.

Up to 40.1 and 61.6% of respondents reporting never recruiting the use of a chaperone for examination of sensitive sites such as the anogenital region or breasts, respectively. When using a chaperone, many indicated they were most likely to be recruited for female patients (45.1%), younger patients (43.5%), by patient request (46.4%), or where clinicians were uncomfortable with the patient or the examination (45.6%).

Barriers that respondents perceived may prevent patients from accepting routine inclusion CSE include patient embarrassment (90.3%), patient preference for clinician gender (58.2%), and lack of patient knowledge regarding skin cancer occurrence at concealed sites (54.0%). A total of 24.5% of respondents cited patient preference for non-dermatologists to examine concealed sites, such as dentists for the oral mucosa. Free-text responses also raised concerns regarding balancing the low yield of diagnosing malignancies in sensitive sites versus the possibility of submitting patients to unnecessarily invasive examination.

Conversely, when clinicians were asked about perceived risks of not routinely examining concealed skin, dermatologists frequently cited the possibility of missing a diagnosis of cutaneous malignancy (94.1%). This was followed by risk of medical negligence (65.0%) should a diagnosis be missed and patient perception of lack of thoroughness of the examination (48.5%). Potential for outsourcing of diagnostic responsibility in examining concealed sites to other clinicians was not a commonly raised concern (27.4%).

When nominating the responsibilities of a dermatologist, 40.5% of respondents reported feeling that it was not the dermatologist's responsibility to examine concealed sites as part of routine FSE, while 24.5% of respondents did. By site, most indicated that it was the dermatologist's responsibility to examine the scalp (54.0%), while only 43.0, 20.3, and 19.0% felt it was their responsibility to examine the breasts anogenital and oral mucosae, respectively (Figure S2).

Discussion

The incidence of malignancies such as melanoma and NMSCs in concealed sites should not be discounted. For instance, while only 59.9% of respondents in this study reported always examining the scalp, melanomas arising in this site are not uncommon – comprising 7% of cutaneous melanomas overall and 19% of melanomas of the head and neck.17, 18 Moreover, scalp melanomas are associated with almost double the mortality compared to melanomas on the extremities even when controlling for age, Breslow thickness, and ulceration.17 Similarly, 3–7% of melanomas in women arise on the vulva despite comprising only 1–2% of body surface area, with high mortality rates of up to 70%, hypothesized to be due to later stage at diagnosis.19, 20 However, nevi of the vulva often have atypical histopathological features but benign clinical behavior21 which may create dilemmas in diagnosis and management.

While routinely screening concealed sites as part of an FSE may optimize earlier detection and management of cutaneous malignancies,22 this must be balanced against patient and clinician preferences, sensitivities, and the clinical utility of routine inclusion of sensitive/concealed sites. Regular FSE in populations at high risk for melanoma has been demonstrated to be cost-effective;23 however, it is unclear whether this translates to the broader population and whether this pertains to concealed or sensitive sites. Moreover, anatomical site-specific analysis of screening utility may be necessary to explore the diagnostic yield of routine CSE, given the disparately higher mortality of cutaneous malignancies arising in these sites.

In this Australian cohort, most dermatologists (59.9%) reported examining the scalp as part of routine FSE and believe it is the dermatologist's responsibility to include this site, while the majority do not believe the breasts, oral mucosa, or anogenital region constitute routine inclusion. This differs from a previous survey of dermatologists from the USA, Europe, South America, Asia, and Australia that reported the vast majority routinely examine the breasts and buttocks (93.3%), half routinely examine male genitals and nearly half the oral mucosa, and a third examine the perianal region, although fewer routinely examined female genitalia.24 However, this survey was aimed at dermatologists who participated in the care of patients with high risk of skin cancer and as such may not reflect the practices of the broader dermatologist population, as in our study.24 Similar to our findings, this survey also found that the most frequently cited rationale that dermatologists provide for not examining concealed sites was “patient discomfort” for anogenital areas and “low prevalence of malignancy” for oral mucosa. They also cited “other specialists examine these areas” as a common reason for not examining all sites, which was not commonly reported in our study (27.4% of respondents).24

The majority of respondents to our survey believed that perceived patient embarrassment serves as a barrier to patients accepting the inclusion of concealed sites in the FSE (90.3%), with concerns that routine inclusion could deter patients presenting for FSE. A cross-sectional study of American patients found that 87% of men and 68% of women would prefer to have an examination of genitals, and 95% of women would prefer to have an examination of breasts included in their FSE.25 Preferences of Australian patients with respect to inclusion of CSE are unknown and warrant exploration. It is important to consider balancing potential for patient embarrassment with the diagnostic yield of regularly screening concealed sites.

The use of a chaperone may help alleviate discomfort patients may have and may also provide some medicolegal protection for clinicians;27 however, there is little exploration regarding chaperone use for FSE in the literature. In Australia, the medical board specifies that chaperones should be qualified to observe the examination (such as registered nurses) and be someone who is acceptable to and respects the privacy of the patient.26 Our study indicated that the limiting factor in dermatologists' use of a chaperone was availability. Respondents indicated in free-text responses that they would most likely use a chaperone in several settings such as with younger or female patients, at patient request or where the dermatologist was uncomfortable with the patient or examination. A survey of 480 Australian patients attending sexual health clinics found that women were more likely to prefer a chaperone during genital examinations (up to 32%), with the majority of participants believing the decision for chaperone presence should belong to patients rather than clinicians.28

Our study found that 41% of respondents did not feel it is the dermatologist's responsibility to examine concealed sites as part of FSE. A parallel may be drawn to the screening of ocular melanoma, which is principally diagnosed by ophthalmologists after the development of lesions of concern (as noticed by the patient or other clinicians) rather than routine screening.29 It may be that dermatologists feel that oral lesions are likely to be identified by dentists and oral health clinicians, gynecologists or general practitioners for vulval lesions, and possibly hairdressers for scalp lesions. The responsibility for examination of the anogenital region may be less clear for men who do not necessarily undergo screening for disease in these regions, such as Pap smear examination for cervical cancer screening in women.

Patient education regarding the possibility of pathology in concealed sites and symptoms of concern is needed, accompanied by the importance of self-skin examinations including all sites. Targeting high-risk individuals for cutaneous malignancy may hold greater benefit in this setting. For example, immunosuppressed solid organ transplant recipients are approximately 50 times as likely to develop vulvar carcinomas, and thus, these patients may benefit from risk education to guide CSE.30 Prior studies have shown that education programs in high-risk patients reduce thickness of diagnosed melanomas,31-33 emphasizing the importance of targeting patient awareness on improving melanoma morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Our study represents 45.9% of all Australian dermatologists, and thus, our results may not be representative of the practices of all Australian dermatologists and may be influenced by non-responder bias. Future studies using our same survey questions among different cohorts of dermatologists may be helpful in validating the consensus opinions generated from our survey responses. Similarly, self-reported data could lead to respondents misrepresenting their usual FSE practices and may be subject to recall bias particularly when estimating the proportion of their patient consults were FSE or how frequently they examine concealed sites. However, opinions on barriers perceived by dermatologists towards routine inclusion of concealed sites in FSE are very relevant to informing peer and patient education approaches for best practice. Finally, there is also a need for patient perspectives to be measured, as while most respondents assumed patient embarrassment was a significant barrier (approximately 90%), this requires confirmation, and whether routine use of chaperones may ameliorate this concern.

Conclusion

We have shown that the approach to FSE and inclusion of CSE varies. Based on national skin cancer incidence and mortality data and the responses of dermatologists in this survey, we propose that FSE routinely include the scalp. Consensus opinion did not rule in favor of routine inclusion of breast, anogenital, or oral mucosa. Patient education regarding the importance of self-examination, including concealed sites, is key – particularly for those at increased risk for cutaneous malignancy. Furthermore, standardized training for dermatologists in identification of malignancies involving mucosal sites may be warranted in order to optimize diagnostic yield at these sites. It is necessary to establish professional guidelines to delineate the responsibility of dermatologists and safeguard the profession medicolegally.

Acknowledgment

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.