Exploratory insights into audit fee increases: A field study into board member perceptions of auditor pricing practices

Funding information: ESCP Business School, Grant/Award Number: ERF 2018-07

Abstract

Audit research documents audit fee discounts associated with an auditor change, and that audit fees revert to average levels within a few years. This paper provides exploratory insights into the perceptions of board members vis-à-vis pricing practices used by auditors to achieve audit fee increases. In semi-structured interviews with 12 respondents (10 board members and two audit managers), we elicit perceptions on initial audit fee discounts, auditor pricing practices and client reactions to these pricing practices. The key findings indicate that auditors combine two pricing practices to achieve audit fee increases. First, they negotiate higher fees prior to the annual audit cycle, citing changes in client structure/size and the institutional environment. Second, they charge higher than negotiated fees after completing the audit (‘extra-billing’), citing justifications such as chargeable hour overruns and findings warranting additional work. Potentially, such auditor pricing practices have negative implications for audit quality and damage the auditor–client relationship.

1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Prior research has consistently documented that audit fees for first-year audits are substantially lower, because incoming auditors undercut incumbent auditors (e.g., Desir et al., 2014; Ettredge & Greenberg, 1990; Ghosh & Lustgarten, 2006; Hay et al., 2006). If the audit fee discount is so great that audit fees are lower than audit costs, this pricing strategy is referred to as lowballing (DeAngelo, 1981).1 Auditors will then try to achieve subsequent audit fee increases2 throughout the auditor–client relationship to compensate for prior audit fee discounts. Alternatively, they can try to provide other, higher margin non-audit services (NAS) to the audit client that subsidize the audit engagement.3

Audit fees increase in the years following an audit tender and revert to ‘normal’ levels within a few years (Collier & Gregory, 1996; Ettredge & Greenberg, 1990; Ghosh & Siriviriyakul, 2018; Simon & Francis, 1988). However, prior audit research has not examined how these audit fee increases are achieved, as only few studies examine audit fees over time and within an auditor–client relationship (de Villiers et al., 2014). Specifically, it is unclear which pricing practices are employed by auditors to achieve audit fee increases, what justifications are put forward by the auditor, how clients react to these billing practices and how these practices might affect the auditor–client relationship. This paper reports exploratory insights from a series of 10 semi-structured interviews with highly experienced board members, some also with prior professional experience in auditing, from a broad range of industries.4 Additionally, we interviewed two audit managers5 to complement and contrast the board members' perspectives on audit fee discounts and lowballing, and the potential implications of auditor pricing practices for the auditor–client relationship and audit quality.

Most board members expect audit fee discounts in audit tenders. Although not the main distinguishing factor between audit firms, board members appear to exploit the fact that auditors try to undercut one another by exercising pressure on their favoured audit firm to lower their proposed audit fee. Surprisingly, only a few board members seem to link initial audit fee discounts to future fee levels, in that they expect subsequent increases if initial audit fee discounts are extensive.

We identify two auditor practices to achieve audit fee increases. These practices are similar to common negotiation tactics documented in the relational selling literature in marketing. First, auditors seek to achieve audit fee increases through renegotiating audit fees prior to the annual audit cycle. They utilize information they have prior to the start of the audit cycle such as new legislation or regulatory requirements, as well as changes in the client's structure or client growth. Second, auditors seek to achieve audit fee increases by billing amounts that are higher than what has been negotiated (‘extra-billing’).6 Justifications for extra-billing are based on factors that are unforeseen, or which can be framed as such, such as additional audit workload following audit findings, the need to involve technical experts, increases in expenses, unforeseen legislative changes and insufficient information or data provided by the client.

We find that some board members feel deceived when fee increases are forthcoming, and more likely so when the auditor engages in extra-billing, when auditors put forward justifications not beyond their control and when the audit fee increases are not communicated in a timely manner. Depending on the specific justification and the timing for communicating the audit fee increase, we find that extra-billing can damage the auditor–client relationship. Clients will often reject the desired audit fee increases, especially extra-billing, and/or negotiate the extra-billed amount. Moreover, some board members think that, given the initial audit fee discounts, this scenario may have negative implications for audit quality, for example, because they fear that auditors might react adversely by cutting audit workload. Other board members, however, feel that the audit profession's regulatory environment guarantees a sufficient level of audit quality.

Our paper contributes to the literature by examining auditors' actual billing practices and undertaking a theoretical discussion of the related mechanics and dynamics between auditors and board members. Field research is increasingly difficult in an environment so conscious about firm and client confidentiality. However, in order to improve our understanding of actual billing practices and related interactions with audit clients, field research based on real situations is essential (Gibbins & Jamal, 1993). Our exploratory qualitative research explains how auditors achieve the audit fee increases documented in the prior archival literature over the course of the auditor–client relationship. We document board members' perceptions around these audit fee increases and provide insights into potential consequences for the auditor–client relationship and audit quality.

Our research can also serve to stimulate and inform future research on auditor pricing practices in audit tenders and over the course of the auditor–client relationship. For example, it would be important to know more about the potential impact that different pricing practices, and any failure to achieve audit fee increases after initial discounts, might have on audit quality. Given the recent introduction of mandatory audit firm rotation in Europe,7 the opportunity to offer initial audit fee discounts or even to lowball in audit tenders might become more frequent. However, audit tenders are costly,8 which will likely increase the pressure on auditors to achieve subsequent audit fee increases. Hence, auditor pricing practices to increase audit fees will become more important.

Our findings, although exploratory, have several implications for auditors, audit clients and audit regulators. We find that auditors experience severe pushback by audit clients when trying to extra-bill,9 which can result in a low, zero or—in the case of lowballing—negative profit margin on a cumulative basis. If the increase in audit efficiency due to accumulated client-specific knowledge fails to compensate for initial audit fee discounts, auditors have a choice between either ending the customer relationship (and realizing cumulative losses incurred so far due to lowballing, if any) or reducing audit costs by cutting down on the audit workload. Reducing audit workload, other than by improving audit efficiency, can result in lower audit quality—an implication that should concern regulators, auditors and board members alike.

Our paper proceeds as follows: first, we develop a framework for auditor pricing practices by conceptualizing the auditor–client relationship as an interactive series of client and auditor choices and actions, including relevant prior literature and formulating our research questions. We then discuss the prior literature, and the following sections describe our research methodology and our findings in detail. The final section discusses our findings and concludes the paper with limitations, implications and potential for future research.

2 AUDITOR PRICING PRACTICES AND DEVELOPMENT OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

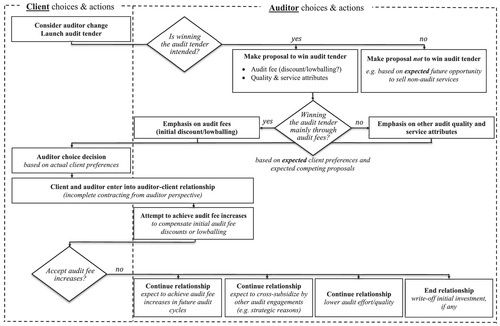

In this section, we conceptualize the auditor–client relationship as an interactive series of client and auditor choices and actions. To derive auditors' incentives, we consider them as expected utility maximizers (Antle, 1982). We describe each phase, discuss the prior literature related to each phase and then formulate our research questions. Figure 1 illustrates the framework.

2.1 The audit tender

After the client has considered an auditor change, either voluntarily, due to dissatisfaction with the incumbent auditor, or mandatorily, due to legal requirements,10 the client will launch an audit tender process. Assuming the auditor chooses to participate, they need to decide whether winning the tender (and thus the client) is intended or not.11 Participating in the tender without intending to win will provide auditors with an opportunity to interact with and nurture relations with board members.

Assuming that the auditor intends to win the tender and the client, the auditor will need to decide whether to offer an initial audit fee discount12 or even engage in lowballing, or not. Lowballing is a pricing strategy (DeAngelo, 1981; Desir et al., 2014) whereby audit services are priced below actual audit (production) costs. Auditors will choose to offer an initial audit fee discount or even lowball if they expect (i) that other competing auditors will offer discounts or lowball as well and (ii) that the client will choose the auditor primarily based on the audit fee level. Alternatively, auditors can choose not to offer initial audit fee discounts or to lowball and instead rely on (superior) audit and/or service quality. In that case, the auditor will highlight attributes that serve to signal audit and/or service quality in order to justify the comparatively higher audit fees.

Initial audit fee discounts and lowballing as a pricing strategy have been consistently documented in prior archival audit research (see the overview by Hay et al., 2006). For example, Ghosh and Lustgarten (2006) show that auditor changes are associated with mean audit fee discounts between 4% (switching between Big 4/Big 5 audit firms) and 24% (switching between non-Big 4/non-Big 5 audit firms). Ettredge and Greenberg (1990) document mean (median) audit fee discounts during audit tenders of 25% (23%). Desir et al. (2014) document audit fee discounts also for post-Sarbanes-Oxley-Act (SOX) initial-year audits. Although initial audit fee discounts and lowballing appear to be common phenomena in audit tenders, these findings do not allow inferring that offers relying more on audit and/or service quality (at higher audit fee levels) would have been unsuccessful. It is possible that every auditor participating in an audit tender offer will offer audit fee discounts because they expect that every other competitor will do the same and that clients will base their auditor choice primarily on price.

2.2 Auditor choice

Clients will choose their auditor based on their actual preferences (e.g., audit quality, service quality and audit fees). Importantly, even if clients do choose their auditor based on audit and/or service quality, they are nevertheless still in a position to exploit the competing offers and receive better initial terms when competing auditors offer discounts in the audit tender.

The prior literature is inconsistent with regard to clients' preferences in auditor choice decisions. On the one hand, prior survey research has identified audit fees as the most important factor in auditor choice decisions (Beattie & Fearnley, 1995, 1998; Eichenseher & Shields, 1983).

However, these studies have surveyed executive management. Changes in corporate governance systems have now shifted responsibility in audit matters away from executive management and towards boards and audit committees. Boards and audit committees have different incentives in terms of corporate governance. From an agency perspective, the primary task of a board member is to monitor and control management (Cohen et al., 2008). Hence, board members will likely consider other attributes more important than executive management.

Indeed, more recent evidence indicates that audit fees may be less important to board members. According to a recent field study on audit tenders, audit fees are the main reason neither for considering an auditor change nor for choosing the auditor. Rather, ‘a convincing presentation based on a quality proposal and the right price is needed to finally win a tender. Price is not a breaking point. The jury decide mostly on other grounds and manage to find a middle ground in case the price is an issue’ (Taminiau & Heusinkveld, 2017, p. 1836).

Similarly, a recent study surveying non-executive board members and auditors shows that board members deem audit quality attributes as more important than audit fees and that auditors overestimate (underestimate) the importance of audit fees (audit quality attributes) (Goddard & Schmidt, 2020). The prior literature has shown that independent audit committee members demand high audit quality and are more likely to choose specialist auditors (Abbott & Parker, 2000). Therefore, higher audit fees are paid by more independent (Abbott et al., 2003) and more active (Bratten et al., 2019) audit committees.

2.3 The auditor–client relationship as an incomplete contract

After the client has chosen their new auditor, the two parties enter into a relationship. Although the actual contractual arrangement has a duration of 1 year,13 both sides can expect that the relationship will have a longer duration. According to transaction costs economics, competition is only feasible in the initial stage, namely, during the audit tender. Recurring contracts that require transaction-specific investments are quickly transformed into one of a bilateral monopoly (Williamson, 1981a, 1981b). The assurance of a continuing relationship is needed to encourage such investments (Williamson, 1979). Both buyer and supplier are effectively ‘locked into’ the transaction to a significant degree (Williamson, 1981a, 1981b) and have an economic incentive to sustain the relationship in order to avoid sacrificing any valued transaction-specific costs incurred (Williamson, 1979).

Incurring transaction-specific nonmarketable expenses gives rise to asset specificity (Williamson, 1979). In an audit context, both parties—the audit firm and the client—make specific investments. The former incurs effort when accumulating client-specific knowledge, for example, to understand the client's organization and its systems. Thus, initial audit engagements are more costly than subsequent audit engagements. Audit effort (and audit production costs), ceteris paribus, decrease over the course of the relationship, in line with better knowledge, for example, of systems and processes. Assuming a constant audit fee level and unchanged client business, the auditor's profit margin will thus increase over time. However, the audit client also makes an initial investment. For example, the audit client has to allocate resources to provide the auditor with information (documentation, representations and explanations) required for acquiring said client-specific knowledge, both for rendering the core service (audit) and for additional benefits, such as recommendations given in management letters. Beattie and Fearnley (1995) cite the avoidance of disruption and loss of management time as one of two important reasons for retaining the incumbent auditor.

Marketing theory identifies bonding as one important factor behind a customer voluntarily engaging in transactions with the same supplier of a service or a product (‘repeat purchasing behavior’, Jacob, 2011). In addition to asset specificity, a bonding effect can also be created by satisfaction, especially when the offers of eligible competing suppliers are somewhat uncertain (Jacob, 2011).

Initial audit fee discounts, and especially lowballing, put pressure on auditors to achieve audit fee increases throughout the relationship. Indeed, the literature documents that audit fee levels revert to a ‘normal’ level by the fourth year (Collier & Gregory, 1996; Ettredge & Greenberg, 1990; Ghosh & Siriviriyakul, 2018; Simon & Francis, 1988).14 In this case, the contract between the two parties is essentially incomplete (Hart, 1988): although the audit tender offer can be characterized as a discounted introductory offer, this ‘introductory’ element (and any associated subsequent audit fee increase) is not made transparent.15

- RQ 1:

What are board members' experiences with—and perceptions of—initial audit fee discounts and lowballing?

The audit fee literature discusses factors associated with higher audit fees or associated with audit fee growth over time, including mandatory International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) adoption (De George et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2012; Raffournier & Schatt, 2018); control deficiencies (Hogan & Wilkins, 2008); an increase in the client's earnings management that causes a higher risk of overstated income (Abbott et al., 2006); increased business risk (Niemi, 2006); increased financial reporting risk (Charles et al., 2010); real earnings management (Greiner et al., 2017); increased audit firm legal liability for cross-listed clients (Choi et al., 2009); pre-nitial public offering (IPO) engagements (Venkataraman et al., 2008); audit committees and their role as a control mechanism in assuring audit quality that prevents decreases in audit workload (audit hours) (e.g., Zaman et al., 2011); and a general increase in audit firm litigation risk (e.g., Venkataraman et al., 2008).

More recent evidence on reasons underlying audit fee changes is provided by the Center for Audit Quality (2018), which analysed the proxy disclosures of S&P Composite 1500 firms. Only 25% of the firms disclose an explanation of audit fee changes (p. 8), citing reasons such as significant transactions (e.g., an acquisition), other non-recurring business transactions or specific one-time engagements (e.g., a compilation engagement, p. 9). Bell et al. (2001) related audit fee growth to an increase in audit workload (audit hours) over the recent years, not to an increase of the price charged per audit hour (hourly rates).

- RQ 2:

What practices do auditors employ to achieve audit fee increases over the course of the auditor–client relationship, and how do they justify audit fee-increasing pricing practices to their clients?

2.4 Client reactions to audit fee increases

Different client reactions to fee-increasing pricing practices are possible, ranging from rejection to acceptance. We posit herein that feelings of ‘fairness’ and satisfaction are important in influencing the client's reaction.

Negotiated audit fees should serve as an anchor. Audit clients are aware of the fact that audit effort (and audit production costs), ceteris paribus, should decrease over the course of the relationship, in line with the auditor accumulating client-specific knowledge and gaining a better understanding of, for example, control systems and processes. The auditor, on the other hand, is aware of the transaction-specific costs incurred by the audit client during the (costly) audit tender, and that an auditor change would require the client to ‘write-off’ these investments. The client can be assumed to be aware that the auditor knows that another audit tender would be costly and that the client thus has a certain motivation to avoid changing their auditor. As such, an auditor acting upon this knowledge could be viewed as engaging in opportunistic behaviour aiming at exploiting the client's initial investment. The client is more likely to deem these auditor pricing practices as ‘unfair’.

- RQ 3:

How do board members react to the different audit fee-increasing pricing practices employed by auditors?

2.5 Auditor reactions to rejected audit fee increases

If the client rejects audit fee increases in full or in part, the auditor needs to decide whether the working relationship should be terminated, thereby effectively ‘writing-off’ any initial investments. Hackenbrack and Hogan (2005) show that pricing pressure and the incumbent auditor's inability to recover unexpectedly high labour usage increase the probability of an auditor change.

- audit fee increases expected to be achieved in future audit cycles (e.g., the auditor expects that past or different pricing practices/justifications might be successful in the future);

- audit fees generated in other audit engagements (e.g., the client has ‘strategic value’, because they act as a flagship client allowing the auditor to demonstrate expertise in a certain industry or for a type of client firm, which is expected to allow the auditor to retain and/or attract other, economically more viable, clients from the same market segment); and

- decreasing audit costs. Audit production costs can be decreased, for example, by reducing effort or by assigning less expensive staff, both of which will ultimately reduce audit quality (i.e., the auditor ‘can benefit from violating professional standards or lose by refusing to violate the standards’, Goldman & Barlev, 1974, p. 709).

Time pressure has also been shown to have similar consequences. Audit seniors plan fewer audit procedures and are less responsive to client risk (Houston, 1999), and they revert to irregular audit practices, such as not testing all items in a reported sample (Willett & Page, 1996) or signing-off prematurely (Gundry & Liyanarachchi, 2007). An increased workload has also been associated with dysfunctional audit behaviour, such as the acceptance of weak client explanations, superficial document reviews or a reduction in audit work (López & Peters, 2012; Otley & Pierce, 1996). On the other hand, no association has been found between the level of audit fee and the propensity for issuing qualified or going concern audit opinions (Barkess et al., 2002; Craswell et al., 2002; DeFond et al., 2002).

- RQ 4:

From the perspective of board members, what are potential implications that auditors' audit fee-increasing pricing practices have on the auditor–client relationship and audit quality?

3 METHOD

3.1 Research approach

We aim at examining actual auditor pricing practices in auditors' interactions with clients (i.e., board members responsible for audit matters on the client side). Although quantitative research can document initial audit fee discounts, or the undercutting of incumbent auditors' fees and subsequent audit fee increases, quantitative research cannot examine the pricing practices and interactions between board members and auditors that underlie these audit fee increases. We conclude that an abductive approach is suited best in this regard (Saunders et al., 2019), as it combines induction and deduction and uses empirical fact as the starting point (audit fee increases). We inductively derive themes and develop research questions, before mapping them against the theoretical framework (Figure 1). In addition, we analyse and interpret our collected data in the context of the theoretical framework, to work out our contribution.

We decided to collect data by conducting interviews with board members, rather than with auditors. Auditors' pricing practices involve two parties, namely, those who bear the increases and those who impose them. Whereas auditors decide to employ certain pricing practices, it is the board members who experience the pricing practices directly. Additionally, interviewing board members allows us to examine client reactions to these pricing practices and different justifications put forward by the auditor to justify audit fee increases. For example, a potential deterioration in the auditor–client relationship, or even clients initiating an audit tender, will depend on how board members perceive the pricing practices and react to them.

3.2 Interviewees

We interviewed 10 board members (BMs),17 each of whom had broad international professional experience and experience with different audit firms and client companies.18 Their companies were all subject to statutory audits, and in their capacity, they were either a chairperson of the board (if no audit committee was established, in which case the board is responsible for audit tenders) or an audit committee member (if an audit committee was established).19 Furthermore, between them, they had mandates in commercial companies and regulated financial services companies. Interviewed board members have on average more than 30 years of total work experience. Four board members have previous work experience as auditors (average work experience in auditing = 7.6 years), and they hold non-executive roles in a median number of 8.5 mandates. Three of the board members also had an executive role in addition to their mandate(s) as non-executive board members (BMs 1, 8 and 9). Their views were mostly based on interactions with Big 4 audit firms and only some Next 10 audit firms. Table 1, Panel A, presents demographic data on interviewed board members.

| Panel A: Board members (n = 10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifier | Job description | Expert role | Work experience (years) | Audit work experience (years) | Number of mandates | Countries where work experience was gained |

| BM 1 | Independent (non-executive) board member and executive board member (COO) at another firm | Chairperson of the board | >30 | 0.5 | 1 | France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, UK |

| BM 2 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Audit committee member | >30 | >20 | 13 | Luxembourg, UK |

| BM 3 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Chairperson of the board | >30 | 0 | 35a | Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Singapore |

| BM 4 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Chairperson of the board | >40 | 0 | 6 | Italy, Luxembourg |

| BM 5 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Chairperson of the board | >35 | 0 | 6 | China, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Switzerland, UK |

| BM 6 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Chairperson of the board | >30 | 7 | 11 | Ireland, Luxembourg |

| BM 7 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Chairperson of the board | >35 | 0 | 12 | Bermuda, Guernsey, Luxembourg |

| BM 8 | Independent (non-executive) board member and executive board member (CEO) at another firm | Chairperson of the board | >30 | 0 | 1 | Germany, Luxembourg, Switzerland, USA |

| BM 9 | Independent board member and executive board member (CFO) at another firm | Audit committee member | >30 | 3 | 5 | Belgium, Luxembourg |

| BM 10 | Independent (non-executive) board member | Chairperson of the board | >30 | 0 | 5 | Luxembourg, Mauritius, UK |

| Panel B: Audit managers (n = 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifier | Job description | Work experience (years) | Audit work experience (years) | Number of clients | Countries where work experience was gained |

| AM 11 | Audit manager | 7 | 7 | 11 | Germany |

| AM 12 | Audit manager | 8 | 8 | 3 | Germany, Switzerland, USA |

- a Due to specific structures of some sample firms, such as real estate funds, where each individual property is held by individual subsidiaries, each with its own board, this high number is possible. We note that Fich and Shivdasani (2006) report a mean of 3.11 (median 2.89) mandates for US outside board members. However, they only consider board memberships in listed firms. Hence, the number of board memberships would likely be higher if additional memberships in unlisted firms were considered (as for participants in our experiment). Field et al. (2013) report a mean of 2.7 mandates by US board members, and they note that 13% of all directors serve on six or more boards (p. 67). Their sample comprises listed firms only, but it is unclear whether they also count board memberships in unlisted firms.

To complement and contrast these clients' views, especially on initial audit fee discounts and lowballing (RQ 1), and the potential implications of auditor pricing practices on the auditor–client relationship and audit quality (RQ 4), we also interviewed two audit managers (AMs) with 7 and 8 years of total work experience, respectively. Table 1, Panel B, presents demographic data on the interviewed audit managers.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The semi-structured20 interviews began with an introduction explaining the purpose of the study and the need to record the interview, obtain informed consent and assure confidentiality.21 The interview guide comprised seven open-ended questions, each closely following our four research questions.22 The first two questions referred to audit tenders and initial audit fee discounts (RQ 1). The next three questions addressed auditor pricing practices employed to achieve audit fee increases (RQ 2), as well as how board members react and how auditors interact with them when seeking to achieve audit fee increases (RQ 3). The last two questions concerned how BMs (interview BMs 1–10) and auditors (interview AMs 11 and 12) perceive the risks involved in these billing practices (RQ 4).

We found no differences in responses between ‘ordinary’ board members and those with previous work experience in auditing, except for concerns about audit quality being at risk if auditors fail to achieve audit fee increases: these concerns were primarily raised by board members with prior experience in auditing. With respect to the interviews with board members, we reached conceptual saturation after 10 interviews, which is consistent with the literature, in that, on average, basic meta-themes are identified after six and saturation is reached after 12 expert interviews (Guest et al., 2006).

The one-to-one interviews were all conducted in person by the same researcher between 9 July 2018 and 20 August 2018, and they took between 20 and 50 min to complete. Nine interviews took place at the respective interviewees' offices, two in their homes and one in a public space. One interview with an audit manager (AM 11) was held and transcribed in the German language and was translated into English by one of the researchers. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and then analysed based on qualitative content analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 304 ff.). Open coding identified 53 concepts, which were then reduced to 11 themes (categories). A student assistant with previous work experience in a Big 4 audit firm, who was unaware of the research questions, performed a second coding. Intercoder reliability (without resolving any differences between the two coders) was measured by Cohen's kappa (0.74, p < .001), which indicates good intercoder reliability (MacPhail et al., 2016). Appendix A presents concepts, broken down by interviews, and the reduction to themes.

4 FINDINGS

In this section, we present and discuss the findings from our semi-structured interviews. Table 2 presents the themes mentioned in each of the 12 interviews. We include selected interview quotes in this section, whereas Table 3 provides additional quotes (categorized by the 11 themes).

| Identifier | RQ 1 | RQ 2 | RQ 3 | RQ 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clients' experiences with and perceptions on initial audit fee discounts/lowballing | Auditor pricing practices for audit fee increases | Auditor justifications for audit fee increases | Client reaction to audit fee increases | Potential implications of audit fee increases | |

| BM 1 | Client tries to minimize costs, while the auditor complains that he has to perform the audit without making a profit | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: regulatory requirements Extra-billing: Technical experts, travel expenses higher than planned and overruns in charged hours |

Unfortunate and a nuisance to have to renegotiate costs after every audit Client never paid the whole amount |

Fixed fee arrangements can have negative implications on audits due to unforeseeable events, which need to be priced in |

| BM 2 | When submitting a bid, Big 4 auditors move in the range of ±20% | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Changes in structure, company growth, changes in legislation Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours, audit findings |

Risk of cutting corners when realized fees are too low and hence, negatively impacting audit quality | |

| BM 3 | When hiring a new auditor, fees were lower than the prior auditor's | Extra-billing | Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours, changes in legislation | Negotiate extra-billed amount and never pay the whole requested amount | Risk in the relationship and audit quality, although the auditor's reputational risk could prevent them from, for example, cutting corners |

| BM 4 | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Changes in legislation Extra-billing: Audit findings |

Negotiate extra-billed amount and did not pay the whole requested amount | ||

| BM 5 | 50% of audit tenders lead to a reduction in fees | Extra-billing | Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours, audit findings | Shouldn't pay unless there is a clear and good reason | Extra-billing has an impact on the relationship but not audit quality |

| BM 6 | 99% of audit tenders lead to a reduction in fees | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Requested extra service Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours, audit findings |

Extra-billing is generally acceptable but can be refused or negotiated | Rejecting extra-billing can have a negative impact on the relationship and audit quality. Audit quality risk might be counteracted by the auditor's reputational risk |

| BM 7 | Experienced price cuts when changing auditors | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Requested extra service, changes in legislation and company growth Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours, audit findings, inappropriate information provided by the client and changes in legislation |

Negotiate the extra-billing, which leads to paying 50% of the initial bill | Risk in the relationship as the client can feel unfairly treated when the fees are not what were agreed prior to the engagement |

| BM 8 | Experienced price cuts when changing auditors | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Requested extra service Extra-billing: Audit findings |

Paid extra-billed amounts because it was immaterial and did not harm relationship | |

| BM 9 | Auditor would be ready to lower their margin in order to get the client | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Requested extra service and company growth Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours |

Extra-billing is only acceptable if it's the client's fault, the auditor had to perform excess work. In other cases, it will be renegotiated | If extra-billing is not paid, audit quality and the relationship are harmed |

| BM 10 | Auditors undercut their competitors, which leads to large price differences during tenders | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Changes in legislation Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours and inappropriate information provided by the client |

Extra-billed amount is negotiated by cutting the extra-billed amount initial invoiced by 50% | Extra-billing harms the relationship |

| AM 11 | Initial audit fee discounts/lowballing in order to buy clients and increase the fees over the course of the relationship | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Changes in legislation and company growth Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours |

Clients tend to accept extra-billing when clients were under stress as well | Risk in the relationship and audit quality |

| AM 12 | Common to offer initial audit fee discounts/lowball for business development purposes | Fee increases prior to the start of the audit and extra-billing |

Fee increases: Changes in legislation and new regulatory requirements Extra-billing: Overrun in charged hours, changes in legislation and technical experts |

Involve the board in order to renegotiate | Extra-billing harms the relationship but not audit quality |

| Panel A—Clients' experiences with and perceptions of initial audit fee discounts/lowballing (RQ 1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category/theme | Quotes (board members) | Quotes (audit managers) |

| 1: Audit fee discounts/lowballing | … especially for the first year, it's the year which is the most expensive because you need to get to know the client … you got to really go deep in this information that you do not need to go through and you might be too quick and if you lower your price … you will not have enough time to spend with the client on your files so you may skip something very important …. (BM 9) | … from a firm perspective too it's like … are you actually going to be able to hire the people and pay the people such that you are able to train them up and you know get good quality people to actually staff these jobs and staff them successfully, cause I mean if you do have to depress wages due to reduction in fees, you are not going to be able to hire not only as many, but also as good of people that you need out of college or other firms or wherever, such that you will not be able to staff these engagements and therefore the quality is going to suffer, that's just kind of how I see it, I mean from the way that we currently do it, I do not necessarily see a better way to do it …. (AM 12) |

| 2: Audit pricing | … of course, in the negotiations, typically what happens is, if we like (Big 4 Audit Firm), but they are like 25% above (another Big 4 Audit Firm), that is a typical practical example, … we will go back and say, look guys, we love you very much, but you are 25% too much so, … they'll make a gesture, they'll meet, you know, they have to be able to say well you know we go 10% less … and the board and management will be able to say, ok look they are by far the better team, the best team we negotiated and they accepted to come down a little bit, ok they are 10% more, 12% more, but maybe maximum 15% more, and then it's justified …. (BM 2) | … what I've seen in practice, at least with the bigger ones [bigger audit clients], … there might be a little bit of a discussion of, alright, do we kind of get our foot in the door, and then increase fees over time …. (AM 12) |

| 3: Audit attributes | …. Auditors are also supervised by the regulators and some of their files are picked up every year and audited by the regulator, so they have to do their work at minimize, there is something they cannot go below as far as quality and control …. (BM 9) | … we actually had direct communication to the AC [audit committee] and said look, the fees should be a million dollars higher on this one, and at that point of time … the CFO wanted to actually tender the audit and the AC thought it would be too expensive to potentially switch auditors, so they accepted our fee so it's, I think, just a matter of relationship and communication …. (AM 12) |

| 4: Auditor choice | … it's interesting because we selected three to actually meet and come present us … only one of them made the effort to meet, no in fairness one of them went and met the financial controller in London but only one met us here, and we wanted them to sit down with us … really find out what was going on …, and they actually got the job in the end and they were not the cheapest they were the middle of the three. (BM 7) | … I believe … especially when talking about the Big 4 that the service … is identical or almost identical, of course there are always differences in the teams … but otherwise the audit service is relatively identical and then there are not too many other starting points in order to differentiate between the competitors, other than the price …. (AM 11) |

| Panel B—Auditor pricing practices and justifications for audit fee increases (RQ 2) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category/theme | Quotes (board members) | Quotes (auditor) |

| 5: Justifications for fee increases | I think the other thing that comes is, matters arise were you need your auditor to look at it and you know if they lowballed the audit fee … they know you are on the hook so then you get it for a big fee on the back end. (BM 6) | … one of the other things … discussed this year is like when we tried to redo the … fee was that we want x amount of increase but yes some of it needs to be under US GAAP, but we do not want all of it on, because if say, we had 500k increase but we show it as onetime special project, our negotiations for future years are, the first thing they'll do is minus 500k from the total and then you cannot build on your base fee, …. (AM 12) |

| 6: Timing of fee increases | … aside from doing the engagement letter, there should be a fee proposal agreed, … sometimes the engagement letter is done so late, it's almost prepared and signed at the same time, as the audit report is signed … there should be a pre-audit meeting where they look at what has changed, and then that should generate a reassessment of fee levels …. (BM 7) | … ideally all special effects are known beforehand and to use a classic example: 31.12. is the year end, and you finished, then you meet again in May and say, ok, what about next year? We plan the audit etc., and are there any special things happening and what about fees …. (AM 11) |

| 7: Extra-billing | … if they do it well, and they want to be successful, the minute they have a potential overrun because of a big problem, discovered a fraud somewhere or you find the whole accounting team left … they come in for the interim in November and then they say you are supposed to deliver this and that and nothing was delivered, that's when you should be saying, potentially we got a problem, right? So clients want to know very early on if there is a potential problem, but the clients hate and often would reject, they would not accept, you do the audit, there's no indication there's been problems, or big problems or overruns and after the audit, you know, or just before signing you say, we have got huge overruns, it's like surprise, typically they would say we deliver a no-surprise audit which means you manage people's expectations, if they want to recover their fees they need to come around as soon as it becomes reasonably clear that there will be a problem but if you do that at the end, you got very little chance. (BM 2) | … when you show up at the end and say well here is the three things that we need money for, because they happened during the year, it's generally, I've seen you get bit more pushback on it and I think part of it too is generally well, US Tax reform happened December, why are you waiting till March to claim that you need money for it …. (AM 12) |

| 8: Justifications for extra-billing | … the client is led to believe that he is going to pay less … audit fees tend to increase plus … that suddenly at the end of the audit cycle suddenly there is ‘Oh, we had extra costs’ and they try and dump fees on you, which you know they say is because there have been unforeseen hours spent etc., etc. (BM 5) | … they had a really complicated supplier agreement which was negotiated every year, and every year we needed input … and more or less a full technical memo written on it, and I think the first three years it was, you needed to involve a technical specialist, yeah, we'll pay for it … and then the fourth year was, no, this is a reoccurring contract you should have included it under your original fee …. (AM 12) |

| Panel C—Client reaction and implied risk of extra-billing (RQs 3 and 4) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category/theme | Quotes (board members) | Quotes (auditor) |

| 9: Risk of extra-billing | … risk is at the level of the auditor themselves, … cutting corners, yeah there is such a reputation at stake for these boys that, Ok, I've seen better and not so good audit managers and teams etc. but by and large they do what they need to do, … I've had cases, where I think the auditors slipped up, but not to an extent that I thought it was material or big risk. (BM 3) | When someone does not want to pay the service I performed, in the form of after billing, I would have difficulties to audit the next year because at the end of the day it's a question of independence … when he does not pay what I need to spend in order to make a margin or to make a bearable business, then at the end of the day independence is somewhat endangered …. (AM 11) |

| 10: Tactics to prevent extra-billing | … I would be confident that certain firms would say, ok we are going to quote 50 thousand for this we are already paying let us say 100 thousand but the firms already thinking, but ok we'll make it up in further years, that's an extreme example but what we did with this particular case where we just rotated the auditor, we said well ok we want this fee locking in for three years …. (BM 7) | N/A |

| 11: Extra-billing negotiations | … it's always difficult to quantify what they have actually done, they usually give you a list of things, areas they had to do additional work, but it's not very specific, … maybe you got a slightly lowballed or slightly understated or underestimated fee basis, but you then … cannot tolerate every year sort of having consistent quite material excess fee, service fee charges on top, … it's always better in the end for them to go through the embarrassment of saying well actually here is our bill and it's 65,000 and not 45,000, there was some extra work, they know it's more difficult after the event for the client to say well, we are not paying that, but I think it's one of those things that, as a client, you get the audit done, it may work out very nicely towards the fee, or there may be an overrun, but it's like it's annual, it's gone away now, do not really have to think about it until the next year, of course next year no one's been proactive and done anything about it so you are probably back in the same position …. (BM 7) | … I believe the willingness-to-pay is higher, the higher the client himself was also under stress … the employees also do not think it's great, that something like new financing comes in just before the end or a merger or other special topics, for them it is also always a total adjustment process and the more they feel it themselves … the higher is the acceptability for it …. (AM 11) |

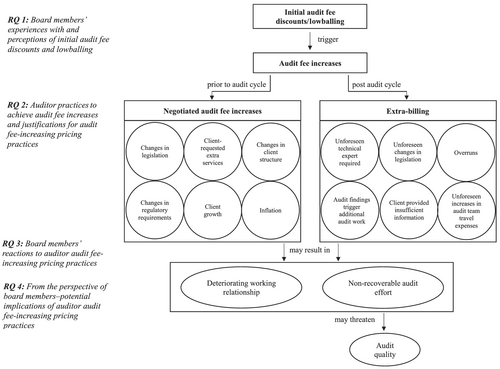

Figure 2 presents a visual depiction of our findings.

4.1 RQ 1: What are board members' experiences with—and perceptions of—initial audit fee discounts and lowballing?

Alternatively, audit fees are only one factor among others to be considered when choosing the auditor (BMs 2, 6 and 8):… the board looks at what is in the best interest of investors if we feel this is a real good auditor and he charges ten percent more than another … that's not going to make any difference really in terms of the performance, so I think that those smaller differences are not going to be the deciding factor. (BM 5)

One board member was willing to accept somewhat higher fee levels, but only in return for a better service (BM 2). Overall, our findings strongly suggest that the importance of audit fees in audit tenders is overrated.… I think most serious organizations will not look at fees from the beginning as their main, they look at people, service, all these things, because you have got to deliver and meet the deadlines, and if you're operating in many countries, you got to make sure you're well served, so fees are an important component, but I don't think it's the first component …. (BM 2)

Clients seem nevertheless to exploit the fact that auditors try to undercut one another, in order to pressure their favoured audit firm to lower their proposed audit fee. However, some board members also reject offers that are so low that they expect future audit fee increases (see next paragraph). Other motivations for initial audit fee discounts or lowballing that have been prevalent in the past, such as selling NAS to subsidize audit engagements, have become obsolete due to recent changes in regulation (BM 2).23 We have some indication that the same change in regulation causes some auditors to enter an offer for audit services at very high fees in the tender. This high fee offer makes it unlikely that it will be successful (‘reverse lowballing’), so that the auditor remains eligible for providing NAS to this client (AM 12).[F]irst of all, guys, you never showed us the proper price, you did not investigate properly what [sic!] your time was going to be spent. (BM 3)

… other firms, without naming them, have this attitude of lowballing and then ripping them off, and we knew that was going to come … I think it is dishonest when you do it as a strategy … the assumptions you are working on are not realistic …. (BM 2)

Auditors, on the other hand, engage in offering initial audit fee discounts or lowballing on the assumption that clients perceive audit services as nearly identical and that the audit fee is therefore the only differentiating factor (AM 11). Auditors also offer initial audit fee discounts for strategic reasons, such as opening up new market segments (AM 12).… some of the smaller firms … have said, you know we would like to have you as a client, we would like to do the audit, because we think we can bring down the cost … we actually rejected the proposal because it was so blatant … we knew the second year … it would be a serious step change back to levels we were more used to seeing. (BM 7)

4.2 RQ 2: What practices do auditors employ to achieve audit fee increases over the course of the auditor–client relationship, and how do they justify audit fee-increasing pricing practices to their clients?

Renegotiating the audit fee occurs prior to the audit cycle, that is, after the auditor has been approved by the annual general meeting and before the audit cycle starts (BM 9). Auditors include special client requests (which might have been out of scope from an audit planning standpoint) in the ongoing audit engagement, rather than negotiating an additional separate engagement. This strategy results in a higher ‘base’ audit fee, and it increases the starting point in the following year's negotiations (AM 12). A minimum audit fee increase is justified by auditors ‘indexing’ them to achieve an annual increase that corresponds approximately to the 2% inflation rate target set by the European Central Bank (e.g., BM 6). This minimum audit fee increase is likely to be constant throughout the whole auditor–client relationship. In addition, auditors use different justifications for renegotiating audit fee increase, such as legislative or regulative changes (BMs 1, 2, 4, 7 and 10), client growth (BMs 2, 7 and 9) or changes in the client's accounting system (BM 2).… you may have, from one year to the other, increases. Never decreases. But you usually in case of increases discuss that with the auditors. I mean, if you have, as you may expect, a good relationship, there is a transparent discussion and you must take into account that, over the years, we had a lot of regulations, also on the audit field there is their own checks, so this is why sometimes I happen to have discussions. (BM 4)

The second practice involves extra-billing the client after the audit has been completed, whereby a bill is presented that exceeds the initially negotiated amount. All 10 board members mentioned having experienced this practice, and sometimes it is not communicated until the after audit has been completed (e.g., BMs 2, 3, 5 and 7). Correspondingly, one of the audit managers mentioned having communicated extra-billing after issuance of the audit opinion (AM 12). Other board members experienced communication of extra-billing during the audit cycle, as and when issues arose that would justify some form of extra fees (e.g., BMs 2, 4 and 9).… they know that they are renewed because you should renew your auditor at the AGM [annual general meeting] … that's when we ask for the planning and then, because I know I've always asked the fee and then they say yeah, but you know we would like to increase, and then they put it in the engagement letter, the engagement letter always has the fee in it …. (BM 9)

There is a variety of justifications that auditors put forward in order to justify extra-billing. The justification cited most frequently by nine out of the 10 board members (BMs 1–3 and 5–10) was unforeseen hours spent by the audit team. The second most common justification (mentioned by six out of the 10 board members) was audit findings that require additional audit work (BMs 2 and 4–8). Two board members referred to a situation where the auditor argued that the client had provided information in a manner that required the auditor to repeat audit tasks (BM 7) or insufficient information, again requiring more audit work (BM 10). One board member (BM 1) and one audit manager (AM 12) mentioned the need for technical experts, due to client specificities. A second justification brought forward also during the audit cycle was in the form of unforeseen regulatory or legislative changes, which may affect audit procedures (BM 7 and AM 12). For example, one audit manager (AM 12) mentioned a change in Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) standards during the current audit cycle. Lastly, some board members had experienced the auditor arguing that travel expenses had exceeded the previously agreed upon amount (BM 1).…. And when there are big issues and you're thinking that … everything has gone on time, then the bill comes in saying, yes well, it's 20,000 over, because we had all this extra work, that's when you get the unwelcome surprises and that happens too often …. (BM 7)

If the audit goes smoothly, then, you know, it's unfortunate for them in a certain way, because they then only get that fee and of course they'll look for every opportunity to add. (BM 6)

4.3 RQ 3: How do board members react to the different audit fee-increasing pricing practices employed by auditors?

Interestingly, auditors seem to know that client frustration tends to be higher when potential extra-billing is not communicated during the audit process and is only raised after the audit has been completed (AM 12), working on the assumption that extra-billing will be more successful if the client is also ‘under stress’ (AM 11). Involving the board is mentioned as a strategy to increase the success of extra-billing (AM 12).They will come to you and they will say we've had a 30,000 euro run over, and that 30,000 is based on the time spent … and then the negotiation starts and then usually they say, you know … we'll propose 12,000 and then you go, ‘yes, but …’ and you settle on 8; that's kind of what happens …. (BM 3)

There seems to be considerably less client pushback on annual renegotiations of the audit fee prior to the audit cycle, and only one board member mentioned them as a nuisance (BM 1).

4.4 RQ 4: From the perspective of board members, what are potential implications that auditors' audit fee-increasing pricing practices have on the auditor–client relationship and audit quality?

Many board members perceived extra-billing as an auditor pricing practice that can damage the auditor–client relationship (BMs 3, 6, 7, 9 and 10). They often felt ‘duped’ or treated unfairly, and one had considered switching auditors and initiating the audit tender process (BM 5).24 In addition, they generally felt that extra-billing is a symptom of failures in the auditor–client relationship and that through good planning and communication, extra-billing could be avoided (e.g., BM 10). One audit manager (AM 12) confirmed the view that it can threaten relationships:

… I think there are obviously some failures, and again I think that's just due to individuals not handling the relationships as they should, because at the end of the day, that's what it's about, it's about maintaining a good relationship and communication. So, I think the perfect process would really be all about communication, as long as you know in advance what to expect and why, that's fine. (BM 10)

Our findings are mixed as far as potential implications for audit quality are concerned. Some board members suggested that a failure to achieve audit fee increases may have negative effects on audit quality (BMs 2, 3, 6 and 9), and some of these specifically mentioned potential measures that auditors might take if achieving audit fee increases, especially extra-billing, fails. First, board members suspected that auditors might plan the audit based on the audit fee level, and not with a view to the resources needed to conduct an audit that reduces audit risk to an appropriate low level and in accordance with audit standards (BM 2). Second, board members suspected that audit teams might be staffed in line with a constrained time budget, which may cause the audit team to engage in ‘cutting corners’, such as premature sign-offs or failure to recognize or to act on important information (BMs 2 and 9). Interestingly, the two audit managers shared similar concerns, such as the audit firm's inability to hire suitable staff for the audit engagement (AM 12).

… I mean, if there is significant price pushback, I think that is the thing that can impact most the quality of the service. I'm not sure it impacts the quality of the audit, auditing has become very much standardized, computerized …. (BM 6)

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

5.1 Board members' experiences with initial audit fee discounts, lowballing and expected subsequent audit fee increases

Most board members expect audit fee discounts (i.e., lower audit fees compared with the audit fees charged by the incumbent auditor) in audit tenders. However, not all of them perceive them as a deliberate pricing strategy, because they consider a range of ±20% for audit fees to be normal, even for audit firms on the same audit firm tier. This range is consistent with the average audit fee discounts reported in previous archival audit research (Ettredge & Greenberg, 1990; Ghosh & Lustgarten, 2006; Hay et al., 2006).

Because the auditor may not ‘pass on’ efficiency increases by voluntarily lowering audit fees while the relationship is ongoing (‘… you may have, from one year to the other, increases. Never decreases …’, BM 4), the client initiates the audit tender process to realize the potential for lower audit fees due to audit firm efficiency increases (Hay et al., 2006).25 Conversely, excessive initial audit fee discounts (including lowballing) cause some board members to expect subsequent audit fee increases, and thus, they reject these (‘blatant’, BM 7) offers. When auditors do offer initial audit fee discounts, they do so with a view to winning the audit tender. Sometimes audit fee discounts are offered as a means to entering a new market for a certain type of client or industry and subsequently acquiring additional business and clients in that market.… they are even talking about using artificial intelligence to do a lot of the basic audit work … I was at a presentation by them recently where they talked about … receiving a dump of all the data and therefore the transaction audit would be a 100%, which, if it works, great, I mean then you don't need people pulling out invoices of the files and things …. (BM 6)

The relational selling literature in marketing (Geiger, 2017)26 has documented two similar negotiation tactics that are widely applied in complex B2B transactions to elicit a customer's willingness to pay when ex ante information is limited, namely, ‘get commitment first’ and the ‘door opener’. Under the first tactic, the buyer (client) is persuaded about the eventual advantages of the seller's offer and becomes committed, which then paves the way to a higher price. The ‘door opener’ tactic is employed by sellers when they are missing precise information about the other party, such as willingness to pay. An opening offer misses essential features but leaves the price in an acceptable range. This tactic has a safeguarding function by keeping the focal supplier in the negotiation process, if competition is strong.

Our findings are mixed as far as the importance of audit fees in clients' auditor choices is concerned. The majority of board members do not consider audit fees to be a particularly important factor in their auditor choice decisions, which is consistent with more recent evidence (Goddard & Schmidt, 2020; Taminiau & Heusinkveld, 2017). A minority consider an audit as a standardized service and will select their auditor primarily based on audit fees. However, clients that do not consider audit fees to be the primary factor will nevertheless exploit auditors' offers of initial discounts. Nonetheless, initial audit fee discounts continue to be a common pricing strategy, because auditors believe that fees are the most important factor in board members' decisions.

5.2 Subsequent audit fee increases over the course of the auditor–client relationship

Transaction costs economics suggests that the relationship between the auditor and the audit client is quickly transformed into a bilateral monopoly (Williamson, 1981a, 1981b). Both parties are ‘locked into’ the relationship due to the transaction-specific investments made at the initial stage. They are strategically situated to bargain over the disposition of any incremental gain whenever a proposal to adapt is made by the other party (Williamson, 1979). Clients appear to be aware of the higher workload associated with first-year audits and view it as an investment that the auditor must make. Interestingly, we do not find evidence that board members engage in opportunistic behaviour by using this investment as leverage against the auditor in subsequent years. Subsequent audit fee increases, especially extra-billing, however, can be interpreted as an attempt by the auditor to ‘exploit’ the client's initial transaction-specific investments. Changing the auditor would require the client to ‘write-off’ those investments. The extent to which the auditor is economically compelled to ‘exploit’ the client's transaction-specific investments depends on the extent of their prior offering of audit fee discounts or lowballing.

Auditors employ two practices, which are commonly combined, that is, renegotiating the agreed audit fee prior to the beginning of the next audit cycle or billing an amount that exceeds the initially negotiated amount set out in the engagement letter after the audit has been performed (‘extra-billing’). With extra-billing, it is difficult for the client to determine whether the auditor's original planning underlying the offer made in the audit tender was deliberately too low, or was very optimistic, or was based on insufficient audit planning, or was truly caused by factors that came up during the audit cycle.

Making an offer that is deliberately too low, and subsequently increasing audit fees, would be considered opportunistic behaviour by the client, which in turn would decrease satisfaction and thus bonding. Insufficient audit planning is also considered ‘unfair’ by the client and decreases satisfaction. Indeed, the few board members who expected subsequent audit fee increases used terms such as ‘dishonest’ and ‘unwelcome’, and hence, it is essential for the auditor to frame extra-billing as unexpected and unavoidable, by citing justifications that are beyond the auditor's, or even better both parties', control.

Again, we note a couple of similarities when comparing auditor pricing practices to negotiation tactics examined in the relational selling literature (Geiger, 2017), in that extra-billing resembles the ‘sneak in’ and ‘stealth issue’ tactics (Geiger, 2017). Under the ‘sneak in’ tactic, the seller introduces an important, previously unaddressed issue in a by-the-way fashion, such as an extra service offered. Similarly, the auditor often justifies extra-billing through additional specialist services or extra field work that turned out to be necessary during the audit. Under the ‘stealth issue’ tactic, an issue is introduced into the contract that is not discussed actively. An example mentioned in the relational selling literature is travel expenses, which we find are used to justify extra-billing.

5.3 Board members' reactions to audit fee-increasing pricing practices employed by auditors

Auditors find themselves receiving significant pushback on their extra-billing. We have some indication that board members' acceptance of extra-billing differs depending on client size, in that larger clients are less willing to accept extra-billing compared with smaller clients (BMs 2 and 5). We speculate that this difference might be due to larger clients having higher bargaining power. Our findings indicate that the earlier extra-billing is communicated to the client, and the better it is justified by reasons beyond the auditor's control, the lower the likelihood of client pushback. Nevertheless, renegotiating the audit fee prior to the audit cycle, and even more so negotiating the extra-billed amount, can drain both time and resources. Inadequate communication regarding audit fee increases and particularly extra-billing is not beneficial to the working relationship and poses a risk to both parties.

5.4 Potential implications of audit fee-increasing pricing practices from the perspective of board members

Additionally, our findings indicate that when auditors fail to achieve sufficient audit fee increases to compensate for initial audit fee discounts, then audit quality can be at risk, because effort and/or staffing might be based on the available budget rather than the assessed audit risk. Prior research has shown that audit fee pressure can be associated with lower audit quality (Bierstaker & Wright, 2001; Ettredge et al., 2014) and by accepting higher audit risk (Coram et al., 2004). Similarly, de Villiers et al. (2014) suggest that auditors' failure to recognize upward audit fee changes soon enough may imply a risk of under-auditing.

Concerns about audit quality being at risk have been raised by several board members (BMs 2, 3, 6 and 9), and some have mentioned specific strategies auditors could employ to compensate a failure to achieve audit fee increases, such as planning the audit with a few to audit fee level rather than audit risk (BM 2), staffing and ‘cutting corners’ (BMs 2 and 9). Interestingly, these concerns are raised primarily by those board members who have prior experience in auditing (BMs 2, 6 and 9). It seems plausible that board members with prior experience in auditing are better able to appreciate the potential consequences of audit fee pressure on audit quality in general and the specific strategies auditors may employ under audit fee pressure. Overall, auditors' pricing practices appear to pose a risk to the auditor–client relationship and may negatively affect audit quality.

Our results have several implications for auditors, clients and audit regulators alike. We find that auditors increasingly experience severe pushback by clients when trying to extra-bill their clients. Where the profit margin remains negative on a cumulative basis, auditors have a choice between two options: either ending the customer relationship (and realize cumulative losses incurred so far) (Hackenbrack & Hogan, 2005) or reducing audit costs by cutting down on the audit workload (Hobson et al., 2019). Reducing audit workload, however, also results in accepting lower audit quality and ultimately a higher audit risk and a lower level of assurance. The UK House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee (2019) expressed similar concerns recently, noting that ‘a properly priced and resourced audit “is the only way of getting quality” ’ (par. 142) and consequently recommended giving the regulator more powers over audit fees (par. 153): ‘Audit firms have to choose between sacrificing quality or profits when the audit discovers problems that require extra work […]’ (par. 145).

Some board members, on the other hand, believe that the regulatory environment ensures a sufficient level of audit quality. However, for a couple of reasons, audit clients might not be fully able to ‘measure’ audit quality. For example, the nature and extent of the audit procedures carried out by the auditor are not fully observable by the client. Also, clients might not be fully aware of the requirements set out in the audit standards.27

It is therefore important for both parties to understand, and for audit regulators to ensure, that every individual annual audit cycle is priced with a view to audit production costs. Policymakers may thus consider taking a closer look at audit fee arrangements. Ideally, first-year audits would not be priced at a discount but with a premium that compensates for the higher audit effort associated with them. Indeed, one board member (BM 9) mentioned a one-time extra fee negotiated in this regard.

Another measure to avoid cross-subsidizing audit cycles over the auditor–client relationship might be to require tendering the audit (and appointing the auditor) over several years. If the auditor must be ‘rotated’ after this multiannual appointment, audit fees would need to be negotiated from the beginning at a level that considers the varying audit effort across audit cycles. First-year audits offered at discounted audit fee levels would not have to be subsidized by (potentially) subsequent audit fee increases.

Another measure for consideration by policymakers is the separation of the audit business from other audit firm service lines (‘audit-only’ firms). This separation would effectively rule out subsidizing audit services by NAS, and not only within an ongoing auditor–client relationship (which is achieved by banning the provision of NAS to own audit clients, as currently seen in the European Union [EU]28). This measure is currently planned in the United Kingdom.29

5.5 Limitations

Our study is subject to the usual limitations common to qualitative research. Our findings suggest that auditor pricing practices might have a negative impact on the auditor–client relationship and audit quality, and so this potential impact requires substantiation by future research. We cannot infer if a failure of the auditor to recover incurred audit production costs through renegotiating the audit fee or extra-billing does harm to audit quality in future audit cycles, as auditor reputation and litigation risk might constrain this risk. Additionally, our audit manager sample was too small and too senior in order to assess fully the negative effects that audit fee pressure and associated audit time pressure might have on more junior staff.

Furthermore, while interviewing board members does allow us to identify audit pricing practices underlying audit fee increases, and the justifications put forward to justify these increases, board members as interviewees do not allow us to examine motivation and intent for specific pricing practices. Specifically, our data do not allow us to conclude that the factors put forward to justify extra-billing were truly unexpected, or merely framed by the auditor as unexpected.

Board members' views are mostly based on interactions with Big 4 audit firms and only a few Next 10 audit firms. More research is thus needed to determine whether our findings generalize to audit firms beyond the Big 4 audit firm tier, because it has been shown that the extent to which auditors are successful in achieving audit fee increases differs across audit firm tiers (Ghosh & Siriviriyakul, 2018).

Although this study's research context is Europe, our results should generalize to other jurisdictions, including the United States. The responsibility of audit committees in audit tenders and the composition and role within corporate governance are comparable: in the United States, the audit committee is responsible for the auditor appointment process.30 In the EU, although the final auditor choice is made by the shareholders, the audit committee (or board) has a significant influence on the selection process.31 In the EU, the audit committee is a subcommittee of the board, and the majority of its members must be independent. If no audit committee has been established,32 the board is responsible for audit tenders, and the chairperson needs to be independent. The same applies in the United States, where the audit committee is a subcommittee of the board of directors and is composed of board members and shall otherwise be independent.33 Hence, US audit committees are composed of the same individuals as the respondents in our study.

Overall, our qualitative research must be considered exploratory, in that it yields only initial findings predicated on the perceptual research data examined. Generalizability of our findings, and the potential to develop formal theory, is thus limited. However, our findings do offer the seeds of new theory the chance to emerge, and so they could stimulate further research.

5.6 Avenues for future research

Our exploratory findings open up avenues for future research on auditor pricing practices in audit tenders and over the course of the auditor–client relationship. For example, the extent to which auditors are successful in achieving audit fee increases differs across audit firm tiers (Elliott et al., 2013; Ghosh & Siriviriyakul, 2018)34 and depending on the riskiness of the client as perceived by the incoming auditor (Elliott et al., 2013). However, our understanding of the scenarios in which specific pricing practices are more successful than others is limited. Future research could build on our findings and examine how staff auditors' performance, as well as audit planning by more senior audit staff, differ between engagements for which prior audit fee discounts or lowballing can be compensated by achieving audit fee increases, compared with engagements where the auditor failed to achieve sufficient audit fee increases. The effect of billing practices such as extra-billing on the working relationship and resulting potential auditor switching provide further room for future research. Lastly, we find some first indication that auditors may participate in audit tenders without intending to win (by entering an offer that is more expensive), in order to gain the opportunity to interact and nurture relations with board members, and potentially sell NAS. Whether this is common practice, and to what extent auditors engage in it, is also subject to future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions received from our discussant and conference participants at the 2019 EARNet, two anonymous reviewers and Yuri Biondi, Frank Jacob and Klaus Ruhnke. The authors received financial support for this research under the ESCP Business School European research funding scheme (Project Number ERF 2018-07).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Both authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

All procedures performed in our study involving human participants were approved by ESCP Business School (Project Number ERF 2018-07).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Francis Goddard: conceptualization (equal); investigation (lead); analysis (equal); methodology (equal); visualization (equal); writing—original draft preparation (equal); writing—review and editing (supporting). Martin Schmidt: conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (lead); analysis (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (lead); visualization (equal); writing—original draft preparation (equal); writing—review and editing (lead).

ENDNOTES

- 1 Lowballing is commonly defined as setting audit fees below total current costs on first-year audit engagements (DeAngelo, 1981, p. 113). Thus, not every initial audit fee discount qualifies as lowballing. The audit fee discount offered in an audit tender might result (only) in a low or zero profit margin.

- 2 We use the term ‘increase’ to denote any audit fee level that exceeds the audit fees proposed and negotiated for the first-year audit following an audit tender.

- 3 Recent legislation in the European Union and elsewhere prevents auditors from providing NAS to audit clients that are public-interest entities (PIEs), which restricts the potential to subsidize audit engagement. Consequently, achieving subsequent audit fee increases has become even more important. See, for example, Art. 5 EU regulation 537/2014 (European Commission, 2014a), which prohibits auditors from providing a broad range of NAS to own audit clients if the clients are listed companies or other types of PIEs. Section 201 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act contains similar restrictions in the United States.

- 4 See the section on methodology for board members' responsibilities in audit tenders within the European Union legal setting, and the discussion and conclusion section for a comparison with the US legal setting.

- 5 We interview audit managers, rather than audit partners, because in audit practice, usually the (senior) audit manager in charge of an audit engagement is responsible for billing. Not involving oneself with billing issues gives the audit partner some room to concede when negotiating with the client and makes it less likely that disagreements over billing issues will harm the relationship between the client and audit partner. The audit managers that we interviewed confirmed that they, and not the audit partner, are responsible for billing issues.

- 6 The interviewees used different terms to describe the same phenomenon, for example, ‘after billing’, ‘overbilling’ and ‘billing for overruns’. We label these billing practices ‘extra-billing’, because they are characterized by a billed amount that is higher than the amount initially negotiated, and the higher amount is communicated to the client only after completion of the audit. The term ‘extra-billing’ has previously been used by Fontaine et al. (2013).