Audit firm tenure, auditor familiarity, and trust: Effect on auditee whistleblowing reporting intentions

Abstract

Mandatory audit firm rotation has been researched for decades with resulting opposition as well as support. Research has mainly treated mandatory auditor rotation at the firm macro level. We submit the client relationship length is comprised of firm tenure and audit team continuity, or auditor familiarity. Increased tenure, at the interorganizational or firm level and interpersonal or individual level, has been shown to increase trust; and further, trust is positively related to employee voice, such as speaking up about fraud (whistleblowing). We conduct an experiment examining whether increased audit firm tenure and auditor familiarity leads to increased trust, which enhances the willingness to whistleblow. We find evidence that suggests auditor familiarity enhances trust, which, in turn, positively influences an employee's intentions to whistleblow. This has important implications for the profession and for future research exploring mandatory audit firm rotation; in particular, the need to include auditor familiarity as a construct.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mandatory audit firm rotation has been discussed and researched for decades with arguments for it having a positive effect on audit outputs as well as support for it being problematic. A series of studies (Arrunada & Paz-Ares, 1997; Geiger & Raghunandan, 2002; Ghosh & Moon, 2005; Johnson, Khurana, & Reynolds, 2002; Mansi, Maxwell, & Miller, 2004; Myers, Myers, & Omer, 2003; Palmrose, 1987, 1991; Petty & Cuganesan, 1996; Stice, 1991) indicate generally that audit firm rotation would not necessarily be beneficial due to the loss of specific client knowledge. This loss of knowledge would theoretically result in increased audit risk during the first years of a new audit firm engagement. On the other hand, more recent research (Brooks, Cheng, & Reichelt, 2012; Chi & Huang, 2005; Davis, Soo, & Trompeter, 2009) argues that mandatory audit firm rotation would be of benefit, decreasing the risk of auditor independence concerns. In the USA, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) issued a concept release seeking comments regarding the implementation of mandatory audit firm rotation (PCAOB, 2011); however, in September 2014, they concluded their 3-year investigation into the merits and disadvantages of mandatory audit firm rotation without implementing additional changes. In contrast, the European Parliament, in April 2014, approved new rules regarding mandatory audit firm rotation in the European Union (Katz, 2014; Köhler, Quick, & Willekens, 2016). The new rules allow for each of the 28 member nations to determine individual tenure limits with the overriding limit of a maximum of 10 years.

Research has predominantly treated mandatory auditor rotation at the firm macro level. The recently released AICPA Code of Professional Conduct (AICPA, 2015) brings in the construct of familiarity threat, considering it from both an individual and firm level. The new code defines familiarity threat as “(t)he threat that, due to a long or close relationship with a person or an employing organization, a member will become too sympathetic to their interests or too accepting of the person's work or employing organization's product or service.” (AICPA, 2015, p. 134) and notes that, in and of itself, it is not a negative but a risk that should be assessed with appropriate quality control in place (AICPA, 2015, p. 24). As it relates to the length of relationship with the client, the construct of familiarity is comprised of two components: firm tenure and audit team continuity. Hence, we argue that it is important to consider this aspect of familiarity, audit team continuity, within the discussion of audit firm rotation.

Increased tenure, at both the interpersonal and interorganizational level, has been shown to increase trust in a relationship. For example, Rennie, Kopp, and Lemon (2010) find that trust is enhanced with increased auditor–client tenure. Whereas excessive trust may weaken professional skepticism (Rose, 2007; Shaub, 1996), Richard (2006) and Rennie et al. (2010) posit that trust is a necessary and critical component of an audit. Relationship trust enhances confidence in each other's reliability, and honesty (Cote & Latham, 2006). Increased trust minimizes uncertainty associated with opportunistic behavior and increases the likelihood of partners taking greater risks (Birnberg, 2004; Cote & Latham, 2006; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Gao, Janssen, and Shi (2011) found that trust is positively related to employee voice—that is, speaking up about workplace issues—and that trust allows the employee to be vulnerable and take risks. Seifert, Stammerjohan, and Martin (2014) show that interpersonal and interorganizational trust mediates the relationship between organizational justice and the likelihood of whistleblowing.

Speaking up about fraud (whistleblowing) is a risk-taking activity. However, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners’ (ACFE) 2016 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse (ACFE, 2016) highlighted the significance of reporting intentions, indicating that 43.5% of occupational fraud in companies with more than 100 employees was initially discovered through tips and is by far the largest source of fraud detection.1 Thus, research into what enhances whistleblowing is important. We explore whether increased audit firm tenure and auditor familiarity lead to increased trust which will positively impact one's willingness to whistleblow.

This research extends the literature in mandatory audit firm rotation, trust, and whistleblowing with the specific consideration of continuity of audit teams. Accordingly, the current study appropriately disentangles the constructs of tenure and familiarity to understand their impact on client employees’ reactions in the event of discovered wrongdoing. The respondents in this study include 235 subjects, serving as proxies for entry-level client employees. In a between-subjects design, subjects completed a hypothetical case with audit firm tenure varied across four conditions and familiarity with the individual auditor, as the construct for audit team continuity, manipulated across two conditions. Our results suggest that continuity of the makeup of audit teams matters. We find that auditor familiarity enhances trust in the auditor, which, in turn, positively influences an employee's intentions to whistleblow. On the other hand, audit firm tenure, in the absence of familiarity, did not produce significant benefits to trust in the individual auditor

This study, from the research design to the results, offers key contributions to both the literature and practice. The separation of the familiarity and tenure constructs provides a different perspective in the literature, as it holds significant implications for future research exploring mandatory audit firm rotation and other issues surrounding the auditor–client relationship. The results of this study substantiate familiarity with the auditor, and thus the past working experiences between client and firm personnel, as the foundation for trust in the professional relationship. While accounting firms offer an umbrella of reputational benefits for their individual auditors (Knechel, Krishnan, Pevzner, Shefchik, & Velury, 2013), our findings highlight for the profession the importance of client familiarity with individual auditors as a key ingredient of trust and, by extension, the enhancement of audit quality in the form of increased cooperation in the auditor–client relationship. As such, this study holds implications for the profession regarding the importance of audit team continuity.

The remainder of our paper is structured as follows: we provide a discussion of the current research related to audit firm rotation and the development of our hypotheses based on trust, auditor familiarity, and whistleblowing literature; we then address methodology and data gathering; finally, we provide our results and conclusions and discuss study limitations.

2 BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

2.1 Mandatory audit firm rotation

The discussion regarding the need to implement mandatory audit firm rotation has been simmering for decades, beginning with the Metcalf Report (United States Senate, 1976) identifying the imaginable necessity of mandatory audit firm rotation in 1976. In 1978, the concept of mandatory firm rotation was deferred and the practice of audit partner rotation was introduced as a result of the Cohen Commission (AICPA, 1978). A decade and a half later, the conclusions of the Ryan commission (AICPA, 1992) suggested that mandatory audit firm rotation has its disadvantages, with the primary concern being that increased audit tenure reduces audit risk due to deep and thorough knowledge of the client's business and related risks.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) returned to the debate again in 1994 but determined that the practice of using a review partner was sufficient (SEC, 1994). In 2003, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) endorsed postponing discussion of mandatory audit firm rotation citing that time was necessary to be able to quantify the success of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act (GAO, 2003). The debate has again been rekindled as a result of the PCAOB resurrecting the issue by issuing a concept release requesting comment regarding the implementation of mandatory audit firm rotation (PCAOB, 2011). In 2014, the PCAOB gave up on its pursuit of mandatory audit firm rotation (Katz, 2014).

Following the global recession in 2008, the European Union began its own inquiry into the benefits of mandatory audit firm rotation. A 2011 proposal initially suggested a 6-year audit firm rotation and the breakup of accounting firms’ audit and consulting services (Chasan, 2014). The goal, as communicated by Michel Barnier, the European Internal Market and Services Commissioner, was to “reduce risks of excessive familiarity between statutory auditors and their clients, encourage fresh thinking, and limit conflicts of interest” (Chasan, 2014). In April 2014, the European Parliament enacted guidelines requiring mandatory audit firm rotation for its 28 member nations (Katz, 2014). Each nation has the authority to establish rotation terms independently, as long as they comply with the maximums established by the European Parliament. The maximum established is 10 years unless certain exceptions are met (Deloitte Academy, 2014). At the end of the initial 10 years, a company can put the audit up for bid and renew the existing audit firm, allowing for 20 years total (Köhler et al., 2016; KPMG, 2014; Tysiac, 2014). The other exception is if the company engages two audit firms to perform the audit, allowing for up to 24 years before rotation is mandatory (Köhler et al., 2016; KPMG, 2014; Tysiac, 2014). Mandatory audit firm rotation in the European Union became effective in January 2016.

As with most controversial issues, there are both proponents and opponents to mandatory audit firm rotation. Those in favor of mandatory audit firm rotation believe that it would be beneficial for two reasons. The first reason suggested by proponents is that there is a link between audit firm tenure and the likelihood that audit firms will support more aggressive accounting choices. The rationalization is that, as audit firm tenure increases, there are greater economic incentives and pressures to accept more aggressive reporting suggested by management (Conference Board, 2005; Hoyle, 1978). The second reason proponents suggest is that rotation of the audit firm would allow for a new perspective on the workings of the company which could possibly uncover issues that had been previously overlooked. In part, this fresh look would serve to reset auditor professional skepticism that may have been impacted as a result of the client–audit firm relationship becoming too friendly (AICPA, 1992; Chasan, 2014; Conference Board, 2005; PCAOB, 2011). Other research (Brooks et al., 2012; Chi & Huang, 2005; Davis et al., 2009) argues that mandatory audit firm rotation would be of benefit.

Opponents to mandatory firm rotation also have a considerable amount of research to provide support for their perspective. Several studies (Arrunada & Paz-Ares, 1997; Cameran, Francis, Marra, & Pettinicchio, 2013; Daugherty, Dickins, Hatfield, & Higgs, 2012; Geiger & Raghunandan, 2002; Ghosh & Moon, 2005; Johnson et al., 2002; Mansi et al., 2004; Myers et al., 2003; Palmrose, 1987, 1991; Petty & Cuganesan, 1996; Stice, 1991) propose that audit firm rotation is counterproductive due to the loss of specific client knowledge possessed by long-tenured audit firms. Jackson, Moldrich, and Roebuck (2008) found that when going concern was used as a proxy, firm tenure increased audit quality. Stanley and DeZoort (2007) failed to find a relationship between long tenure and nonaudit fees and the likelihood of restatement. It is suggested that this loss of client-specific knowledge could lead to in increased audit risk during the first years of a new audit firm engagement.

In addition to the loss of client-specific knowledge, research against mandatory audit firm rotation is built on the foundation that shorter audit firm tenure will result in increased problems in the first years of an audit. Palmrose (1987, 1991) and Stice (1991) report higher litigation risk for audit firms during the early years of an audit engagement. Petty and Cuganesan (1996) and Geiger and Raghunandan (2002) report an increase in audit failures in the earlier years of auditor tenure. Johnson et al. (2002) report lower earnings quality for new audit firms when compared with audit firms with moderate tenure. Myers et al. (2003) find that the magnitude of both discretionary accruals and current accruals is negatively associated with audit firm tenure. Mansi et al. (2004) reported that an audit firm's tenure is negatively associated with the cost of debt. Ghosh and Moon (2005) suggest that audit firm tenure impacts investors’ perceived audit quality. Several studies have focused on the effect of audit partner rotation (e.g., Carey & Simnett, 2006; Firth, Rui, & Wu, 2012). Firth et al. (2012) found that firms with mandatory partner rotation are associated with a significantly higher likelihood of a modified audit opinion than nonrotation firms in less-developed regions. Table 1 summarizes the audit firm rotation research and related papers.

| Study | Construct(s) of interest | Key methodological implications | Primary contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrunada and Paz-Ares (1997) | Examines the effect of rotation on audit costs and quality. | Estimates the explicit and implicit costs of firm rotation. |

Finds an increase in audit costs and distortion competition. Finds a negative effect on quality due to lower technical competence of auditors and fewer incentives for independent behavior. |

| Brooks et al. (2012) | Examines the effect of rotation on audit quality. | Finds quadratic model better fits than linear model. | Finds audit quality increases in early years due to learning effect and decreases in later years due to bonding effect (average turning point is between 12 and 16 years). |

| Cameran et al. (2013) | Evaluated the effect of firm rotation on audit quality as well as audit fees. | Examined the impact of audit firm rotation which has been required in Italy since 1975. | Findings do not support rotation. Audit quality is lower the first three years of a new engagement while audit fees are abnormally higher. |

| Cameran, Merlotti, and Vincenzo (2005) |

Reviews 26 reports by regulators/other representative bodies from around the world. Also examines 33 academic studies (9 opinion based and 24 based on empirical evidence). |

Empirical studies evaluated were grouped based on the relation between firm rotation and the following topics: • auditor independence; • audit quality; • audit costs; • audit market competition; • capital market reaction. |

Finds 22/26 reports do not support the benefits of mandatory audit firm rotation, while the remaining four are in favor. Finds 75% of studies based on empirical evidence conclude against firm rotation, whereas 56% opinion-based studies conclude against firm rotation. |

| Carcello and Nagy (2004) | Examines the relationship between audit firm tenure and fraudulent financial reporting. | Examines firms that engaged in fraudulent reporting from 1990 through 2001. Used both a matched set of nonfraud firms and with the available population of nonfraud firms. |

Finds fraudulent financial reporting is more likely to occur in the first 3 years of the auditor–client relationship. Finds no evidence suggesting fraudulent financial reporting is more likely given long auditor tenure. |

| Carey and Simnett (2006) | Examines the relationship between audit quality and audit partner tenure. |

Examines three measures of audit quality: • the auditor's propensity to issue a going-concern audit opinion for distressed companies; • the direction and amount of abnormal working capital accruals; • just beating (missing) earnings benchmarks. |

Finds for long-tenure observations: • lower propensity to issue a going-concern opinion; • some evidence of just beating (missing) earnings benchmarks. Finds no evidence of a connection between audit tenure and abnormal working capital accruals. |

| Catanach and Walker (1999) | Develops a conceptual research framework in which to view the firm tenure–audit quality relationship. | Examines economic incentives and market structure as endogenous variables with both performance and tenure. | Findings suggest that evaluating mandatory auditor rotation is a complex process that involves more than a simple association test of the tenure–audit quality relationship. |

| Chen, Lin, and Lin (2008) | Examines the relationship between audit partner/firm tenure and earnings quality. | Uses data from Taiwan that requires two audit partner certifications and the disclosure of their names in the audit report. | Finds discretionary accruals decrease as both audit partner tenure and audit firm tenure increase. |

| Chi and Huang (2005) | Examines how audit tenure affects earnings quality. | Investigates the effect of audit-firm and audit-partner tenure on the level of discretionary accruals. |

Finds familiarity helps to produce higher earnings quality, while excessive familiarity results in lower earnings quality. Finds big 5 auditors are superior in obtaining learning experience in the initial period of engagement. Finds the negative effect on earnings quality is more serious for clients of non-big 5 auditors if audit-firm rotation is mandated. |

| Daniels and booker (2011) | Explores loan officers’ perceptions of auditors’ independence and quality. | Determines whether rotation of the auditor firm impacts financial statement users’ perceptions of auditor's independence and quality. |

Findings suggest loan officers perceive an increase in independence when the company follows an audit firm rotation policy. Finds the length of auditor tenure within rotation fails to significantly change loan officers’ perceptions of independence. |

| Daugherty et al. (2012) | Examines perceptions of audit partners related to mandatory partner rotation and the related cooling-off period. | Used structured interviews and surveys of audit partners. | Findings suggest that partner rotation results in increased partner workload as well as lower audit quality due to retraining. |

| Davis et al. (2009) | Investigates the relation between auditor tenure and earnings management. |

Identifies registrants that meet or beat analysts’ earnings forecasts, but who would have missed the analysts’ target in the absence of discretionary accruals. Then determines whether auditor tenure is associated with the frequency with which registrants are able to use discretionary accruals to meet or beat forecasts. |

Finds both low and high audit firm tenure (after 14th year) are associated with low audit quality. |

| Firth et al. (2012) | Examines whether mandatory rotation plays a more important role in less-developed regions. | Uses auditor propensity to issue a modified audit opinion as a proxy for audit quality. | Finds firms with mandatory partner rotation are associated with a significantly higher likelihood of a modified audit opinion than nonrotation firms in less-developed regions. |

| Geiger and Raghunandan (2002) | Examines prior audit reports for sample of companies entering into bankruptcy during the period 1996–1998. | Uses a multivariate analysis to test for the association between the type of audit opinion issued on the financial statements immediately prior to bankruptcy and the length of auditor tenure. |

Results suggest there were significantly more audit reporting failures in the earlier years of the auditor–client relationship than when auditors had served these clients for longer tenures. Also suggests there is an inverse relationship between auditor tenure and audit reporting failures. |

| Ghosh and moon (2005) | Analyzes how investors and information intermediaries perceive auditor tenure. | Uses earnings response coefficients from returns–earnings regressions as a proxy for investor perceptions of earnings quality. | Finds a positive relationship between tenure and perceptions of earnings quality. |

| Hohenfels (2016) | Examines how auditor tenure affects investors’ perception of audit quality | Uses the earnings response coefficient from returns–earnings regression as a proxy for investors’ perceptions of audit quality and employs a sample of firm-year observations from German listed firms between 2006 and 2011. | Finds a nonlinear relationship where investors perceive lower earnings quality during the early and later years of an auditor–client relationship |

| Jackson et al. (2008) | Investigates the relationship between mandatory audit firm rotation and audit quality. | Used both the propensity to issue a going concern and the level of discretionary accruals. | Found that when going concern was used as a proxy, audit quality increases with firm tenure. Level of discretionary accruals did not affect the relationship between firm rotation and audit quality. |

| Jennings, Pany, and Reckers (2006) | Examines whether perceptions of auditor independence and auditor liability are incrementally influenced by further strengthening corporate governance and by rotating audit firms. | Analyzes responses of 49 judges participating in a course at the National Judicial College. The experiment manipulates corporate governance at two levels (minimally compliant with current corporate governance requirements versus strong) and auditor rotation at two levels (partner rotation versus audit firm rotation). |

Finds strengthening corporate governance (beyond minimal Sarbanes–Oxley act levels) and rotating audit firms (compared with partner rotation) lead to enhanced auditor independence perceptions. Also find judges consider auditors less likely to be liable for fraudulently misstated financial statements when firm rotation is involved in a minimally compliant corporate governance environment. |

| Johnson et al. (2002) | Examines the relationship between audit firm tenure and financial reporting quality. |

Uses two proxies for earnings quality: • absolute value of unexpected accruals • the persistence of the accrual components of earnings |

Finds lower earning quality for new audit firms when compared with audit firms with moderate tenure. |

| Kwon, Lim, and Simnett (2014) | Compares both pre- and post-policy implementation and mandatory long-tenure versus voluntary short-tenure rotation situations. |

Uses a unique setting in which mandatory audit firm rotation was required from 2006 to 2010 and in which both audit fees and audit hours were disclosed (South Korea). Provides empirical evidence of the economic impact of this policy initiative on audit quality and the implications for audit fees. |

Observes audit quality did not significantly change compared with pre-2006 long-tenure audit situations and voluntary post-rotation situations. Finds audit fees in post-regulation period for mandatorily rotated engagements are significantly larger than in the pre-regulation period. |

| Mansi et al. (2004) | Examines the relation between auditor characteristics (quality and tenure) and the cost of debt financing. | Examines companies with year ends between 1974 and 1998. | Finds auditor quality and tenure matter to capital market participants. |

| Myers et al. (2003) | Examines the relationship between auditor tenure and earnings quality. | Examines companies with sufficient data from 1988 to 2000. | Finds longer auditor tenure results in auditors placing greater constraints on extreme management decisions in the reporting of financial performance. |

| Nagy (2005) | Examines the effect of mandatory auditor change on audit quality in the unique environment created by the failure of Arthur Andersen. | Argues the demise of Arthur Andersen provides a setting to examine the effect of forced auditor change on the level of audit quality. | Finds audit quality improved for companies forced to switch from Arthur Andersen for smaller companies. |

| Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gomez-Aguilar, and Carrera (2009) | Examines the impact of mandatory rotation on the likelihood of auditors issuing going-concern modified audit opinions. | Rotation of audit firms every 9 years was mandatory in Spain from 1988 to 1995. | Finds no evidence to suggest that a mandatory rotation requirement is associated with a higher likelihood of issuing going-concern opinions. |

| Stanley and DeZoort (2007) | Examines the effect of audit firm tenure on clients’ financial restatements. | Uses matched-pair design to compare companies with and without restatements. Nonaudit fees are used as a proxy for long-tenure independence. | Finds an insignificant relationship between nonaudit fees and the likelihood of restatement. This finding is contrary to the independence concerns related to long firm tenure. |

| Stice (1991) | Examines the relationship between tenure of the auditor–client relationship and lawsuits against the auditor. | Uses a matched-pair design to analyze a sample of companies involved in lawsuits against auditors and a sample of companies matched with the experimental sample. | Finds evidence of an association between pre-audit engagement characteristics of both client/auditor and the subsequent filing of a lawsuit against the auditor. |

The review of the audit firm rotation research and related papers indicates that the behavioral effect of audit firm tenure has yet to be examined in regard to the impact audit firm tenure has on an employee's willingness to disclose sensitive information to the audit firm. Additionally, the consideration of audit team continuity or auditor familiarity has not been included. It is expected that both audit firm tenure and auditor familiarity will influence the relationship between the audit firm and client employees. This relationship can be manifested through the reporting intentions of a client's employee. This is the employee's willingness to freely share sensitive information regarding potential fraud with the audit firm. As the audit firm's tenure and auditor familiarity changes, the relationship with the client's employees could result in increased or decreased perceived security as a result of sharing sensitive information.

RQ: What is the behavioral effect of audit firm tenure on the likelihood of whistleblowing?

2.2 Trust

The trust literature has its foundations in marketing theory, with a predominant focus on antecedents and outcomes surrounding external channel relationships; for example, buyer–seller, company employee and vendor; see Morgan and Hunt (1994). Employing this external channel focus in healthcare relationships and the impact on financial and nonfinancial performance measures, Cote and Latham (2006, p. 301) suggest that trust is a key driver at the core of interorganizational relationships and that “each interorganizational contact creates a transactional history that influences cumulative perceptions of trust, that then guide outcome behavior.” As such, trust is a key ingredient of relationship maintenance, and it develops over time; that is, longer tenure is associated with greater trust (Cote & Latham, 2006). With increased tenure of the interorganizational affiliation, the accumulation of these individual interactions builds trust in the relationship, and this quality enhances the performance of the dyad or partnership. For example, Cooper and Slagmulder (2004) show that trust facilitates numerous outcomes, including the agreement to strive for higher performance outcomes. Baiman and Rajan (2002) demonstrate that costs related to monitoring systems can be reduced when trust is present. De Ruyter and Wetzels (1999) employ relational exchange theory, with its focus on external long-term relationships and repeated interactions, to examine the auditor–client relationship. They also find a significant positive relationship between trust and commitment to the auditor–client relationship, leading to beneficial outcomes of increased cooperation and reduced opportunistic behavior.

Mouzas, Hennberg, and Naudé (2008, p. 1019) posit that the “origin of trust lies in individuals.” However, Fang, Palmatier, Scheer, and Li (2008) examine interorganizational trust between collaborating firms and intraentity trust among the representatives from each of the collaborating firms. They theorize that interorganizational trust at the firm level motivates resource investments, whereas it is the intraentity trust level that promotes coordination at the transaction level. Though the primary focus of much prior literature is at the individual trust level, Fang et al. (2008) suggest it is critical to capture the different levels of trust (firm and individual) to provide a more nuanced and complete perspective. With a focus on intraorganizational relationships, Seifert et al. (2014) find that individual and organizational trust are both key aspects of the relationship between organizational justice and whistleblowing. We extend research on the different levels of trust to the auditor–client channel relationship, and capture both interpersonal and interorganizational trust in our study.

Based on the foregoing, our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1a.An auditee's reported trust in the audit firm will be stronger when the external audit firm establishes a longstanding relationship with the auditee than when they do not.

H1b.An auditee's reported trust in the individual auditor will be stronger when the external audit firm establishes a longstanding relationship with the auditee than when they do not.

2.3 Familiarity

The AICPA Code of Professional Conduct introduces the concept of a familiarity threat, considering it from both an individual and firm level. It defines it as a threat, stemming from a long or close relationship with a person or an employing organization, which could impair a member's objectivity, independence or professional skepticism (AICPA, 2015). The code notes that familiarity, in and of itself, may not have these negative effects, that is, familiarity may not impair independence; however, the threats should be examined and controls put in place to mitigate as needed (AICPA, 2015). In their position papers related to mandatory audit firm rotation, public accounting firms have noted it is critical to distinguish between an auditor's familiarity with a business and its environment that develops over time and is lost in mandatory rotation and the concept of overfamiliarity with management; for example, see PWC (2014).

In accounting literature, familiarity has predominantly been examined within the audit team (Asare & McDaniel, 1996; Favere-Marchesi, 2006). For example, Favere-Marchesi (2006) finds that audit team performance is enhanced by reviewer familiarity with the preparer as familiarity provides the reviewer with knowledge of the preparer's abilities and competencies. He examines the concept of familiarity by comparing audit teams where a manager had either prior involvement or no prior involvement with a senior. Our study also operationalizes familiarity similarly, with the auditee having prior involvement or not having prior involvement with the audit firm or with the auditor.

Gulati (1995) suggests familiarity, captured as repeated interactions among partners, breeds trust. Gefen (2000, p. 727) distinguishes between familiarity and trust, noting “(f)amiliarity deals with an understanding of the current actions of other people … while trust deals with beliefs about the future actions of other people.” He suggests that familiarity and trust complement each other as familiarity reduces uncertainty through the creation of a structure whereas trust reduces uncertainty through creating dependable expectations about future actions. He further notes that, without familiarity, trust “cannot be adequately anchored to specific favorable behaviors” and, as such, is a “precondition for trust” (Gefen, 2000, p. 728). Thus, our second set of hypotheses is

H2a.An auditee's reported trust in the audit firm will be stronger when the external auditor is familiar to the auditee than when they are not.

H2b.An auditee's reported trust in the individual auditor will be stronger when the external auditor is familiar to the auditee than when they are not.

2.4 Reporting intentions

The ACFE (2016) report that 43.5% of occupational fraud, in companies with more than 100 employees, was initially discovered through tips. This remarkable statistic reinforces the importance of research related to both whistleblowing and the factors that influence reporting intentions. Whistleblowing research has laid the foundation for examining auditee reporting intentions to the external auditor as the external auditor is considered an external reporting option.

Research has shown that the intended recipient of the fraud disclosure often influences the judgment and decision process of an auditee's decision to report questionable behavior (Dozier & Miceli, 1985; Gundlach, Douglas, & Martinko, 2003; Hooks, Kaplan, & Schultz Jr., 1994; Ponemon, 1994). Whistleblower research often focuses on either internal reporting or external reporting. While both conditions can be considered on their individual merits, the final decision is often determined by the whistleblower's perceived assessment of the likelihood of retaliation and the receptiveness of management (or whomever they decide to report to). We argue that this assessment is essentially driven by the level of trust the auditee has in the individual or organization.

Several decades ago, several whistleblower studies (Near & Miceli, 1985, 1996; Sims & Keenan, 1998) were conducted to examine the fundamental nature of whistleblowing and identify possible underlying reasons as to why a whistleblower would report a wrongdoing. Research in connection with organizational structure was performed by Sims and Keenan (1998) in an attempt to quantify how it may influence whistleblowing. They found that increased supervisor support and the establishment of a strong and enforced code of formal policies were positively associated with and possibly contributed to an increase in whistleblowing. These factors, it can be argued, increase trust in the individual to whom the fraud is being reported and also the organization. When trust exists, relationship partners, such as the auditee and the auditor, have confidence in each other's reliability and integrity. Trust has been shown to diminish uncertainty associated with opportunistic behavior (Birnberg, 2004; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Morgan and Hunt (1994) suggest that, once trust is established, partners will be more likely to undertake higher risks as the trusting partner believes the other member of the relationship will not act unpredictably. Whistleblowing is considered an activity that possesses higher risk.

A number of studies by Kaplan and colleagues (Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan, Pany, Samuels, & Zhang, 2009; Kaplan, Pope, & Samuels, 2011; Kaplan & Schultz, 2007; Kaplan & Whitecotton, 2001) that examine reporting intentions and the closely connected area of perceived threat of retaliation suggest several factors that influence reporting intentions. Kaplan et al. (2011) specifically found higher auditee reporting intentions in relation to interaction with an inquiring auditor versus a noninquiring auditor. Factors such as how the auditor responds to an auditee's disclosure would influence the sharing of information. An audit firm with high tenure or an auditor with which the auditee is familiar would presumably have a track record of interacting with the client's employees. This long-term interaction and establishment of trust with the individual auditor or audit firm would influence their willingness to share information. Employing internal auditors as subjects, Seifert et al. (2014) demonstrate that both individual trust in a supervisor and organizational trust serve as mediating variables between organizational justice and the propensity to blow the whistle. They suggest that, in addition to clear, fair whistleblowing policies and procedures, it is critical for organizations to establish trustworthiness in the supervisor (individual) and organizational levels to encourage individuals to speak up in the face of wrongdoing. In an attempt to identify the behavioral implications of mandatory audit firm rotation with its resulting lower tenure and auditor familiarity on an auditee's willingness to report questionable behavior, this study addresses the issue of reporting intentions from the perspective of assessing the impact of trust in the firm and the individual auditor on an auditee's reporting intentions. Thus, our third hypothesis is

H3a.An auditee's intention to report questionable behavior will be stronger when the auditee has established a trusting relationship with the audit firm than when they have not.

H3b.An auditee's intention to report questionable behavior will be stronger when the auditee has established a trusting relationship with the individual auditor than when they have not.

3 METHODOLOGY

A 4 × 2 (firm tenure × auditor familiarity) between-subjects design was employed to test the hypotheses, with audit firm tenure varied across four conditions and familiarity with the auditor manipulated across two conditions. A total of 235 subjects, serving as proxies for entry-level client employees, completed a hypothetical case and responded to several scale and demographic questions.

3.1 Participants

This study was pilot tested using undergraduate students from three different state universities. The results obtained in the pretesting were similar to those obtained in the final data collection. The participants used in the final data collection were recruited via Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk) system. Subjects were screened based upon the following characteristics: location (limited to the USA), lifetime Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) approved (required to be greater than or equal to 1000), and HIT approval rate (greater than or equal to 95% for all requester HITs).2 These attributes are evident in entry-level employees, and thus the subject pool was deemed appropriate for this study. Each subject received $0.75 for their participation in the study, resulting in an average hourly rate of $4 (Horton & Chilton, 2010).

On average, participants were 40 years old (min: 18 years; max: 74 years) and approximately 46% were male versus 54% female. Participants also reported an average of 19 years’ work experience, which lends support to the participants being comfortable with the basic business terms used in the scenario. Of the sample, 29% reported working with an external auditor in a work setting. Those who had worked with an auditor reported an average of 8 years of experience in this capacity. Table 2 provides more detailed demographic information about the participants in the sample.

| Gender | |

| Male | 46% |

| Female | 54% |

| Age | 40 years |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 73% |

| African American | 13% |

| Hispanic | 6% |

| Asian | 6% |

| Other | 2% |

| Dealt with auditor in workplace | |

| Yes | 29% |

| No | 71% |

| Experience working with auditorsa | 8 years |

| Experience as an auditor | |

| Yes | 4% |

| No | 96% |

| Work experience | 19 years |

- a Only includes those subjects (n = 69) who indicated that they had dealt with an auditor in the workplace.

3.2 Experimental procedures

The hypothetical case used in the study is modeled after the fraudulent act and whistleblowing case in Kaplan et al. (2009), which is employed again in Kaplan, Pope, and Samuels (2015).3 The ACFE (2016) findings indicate that, though fraudulent financial reporting represented 9.6% of cases identified, its fraud schemes reflect the greatest median loss due to fraud ($975,000). As noted by Kaplan et al. (2015), though financial fraud reporting does not usually involve a direct transfer of monies to perpetrators, the individuals typically receive indirect benefit through bonuses and other positive performance based outcomes. This is the scenario in the hypothetical case; that is, the perpetrators are engaging in the behavior to meet forecast expectations.

The case begins with a short description of a mid-size public company. Included in the description is information about the company's requirement, imposed by the SEC, to solicit the services of a public accounting firm to provide an external audit of the company's financial statements. Next, the case describes a scenario that occurs prior to the audit fieldwork is to take place at the company. In the scenario, an entry-level employee of the company overhears a phone conversation between two colleagues about the processing of sales orders.4 One of the individuals in the phone conversation is authorized to approve shipment of products and asks the other to initiate a sales order for a customer, even though the customer has not ordered the goods. The employee with shipping authorization indicates that the channel-stuffing maneuver will be difficult to detect and allows the company to report earnings that will meet consensus forecasts for the quarter. The scenario ends with information about the audit firm who will be conducting the external audit, as well as the individual auditors who will be conducting interviews with various client employees. The case was pretested multiple times with undergraduate accounting students at three universities.5 A version of the case with a description of the variations of the conditions is presented in the appendix.

3.3 Independent variables

3.3.1 Firm tenure

For the length of the audit firm tenure (FIRM TENURE), the subjects were randomly assigned to one of four conditions. In the first condition (NEW), the subjects were informed that the company had hired a new accounting firm to provide the external audit for the most recent year end. In the other three conditions (2 YEARS, 7 YEARS, and 15 YEARS), subjects were informed that the company had retained the accounting firm that had performed the external audit for the company in prior years. The length of the tenure is varied to include short-term relationships as well as a longer term relationship (i.e., 15 years), as various tenure lengths have been discussed in firm rotation proposals (Chasan, 2014; Katz, 2014; KPMG, 2014; Tysiac, 2014). The mean values of reporting intentions for the four conditions were examined and it was determined that there was not a significant difference between zero (M = 56.942) and 2 years (M = 52.613) (t = 0.890, p = . 375) and also between 7 years (M = 55.203) and 15 years (M = 49.481) (t = 1.382, p = . 170).6 As there was not a significant difference, the four conditions were combined into two conditions (low versus high firm tenure).7

3.3.2 Familiar

To examine the issue of familiarity with the individual auditors (FAMILIAR), half of the subjects were informed that the upcoming audit engagement would be staffed by auditors that the client employee, the one who overheard the key phone conversation, has never met before. As such, the individual auditors are new to the audit engagement and would be interviewing client employees for the first time. The other subjects are told that the individual auditors had interviewed the client employee on the past two audits, and thus the client employee is familiar with the engagement team.8

3.4 Endogenous variables

After reading the case, the subjects responded to a number of scale items and demographic questions. Based on the Kaplan et al. (2009) 11-point likelihood scale, subjects were asked about the probability (anchored at 0 and 100%, in 10% increments) of the client employee reporting the questionable behavior to the external auditors (REPORT). Using the trust scale of Cote and Latham (2006), subjects were asked about the level of trust the employee likely placed in the audit firm (TRUSTF) and the individual auditors (TRUSTI). Both items were measured on a 0 (do not trust) to 100 (completely trust) scale in increments of 10. To gauge the subjects’ understanding of the case, two manipulation check questions (MCQs) were asked: one regarding the length of the company's relationship with the accounting firm, and the other about the length of the client employee's relationship with the individual auditors.

4 ANALYSIS

4.1 Manipulation checks

A total of 197 subjects correctly answered the familiarity MCQ (84%), while 194 subjects passed the audit tenure MCQ (83%). This failure rate is consistent with prior studies using MTurk (Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, 2013). Goodman et al. (2013) compared data collection from MTurk samples. They conducted two studies, the first with an 81% MCQ rate and the second with a 66% MCQ rate. They also found English as a second language played a large role with an MCQ rate of 81% for native English speakers versus 61% for participants with English as a second language. Another study by Peer, Vosgerau, and Acquisti (2014) shows that participants with high reputations (high HIT percentage) rarely fail MCQs. Peer and colleagues performed two experiments. The first only incorporated a 95% approval rate and resulted in a manipulation check fail rate of 97.4% in the high approval rate condition. The second study incorporated both a 95% approval rate and a minimum HIT approval of 500. The second study resulted in an 83.3% pass rate for participants in the high pass rate/approval condition. As we incorporated both a 95% approval rate and a 1000 HIT approval requirement, our manipulation pass rate was consistent with the findings of Peer et al. (2014). The elimination of cases where subjects failed to correctly answer both questions resulted in 164 usable cases for the analysis.9

4.2 Descriptive statistics

The relationship between the endogenous variables and each demographic variable is nonsignificant, and thus the demographic variables are excluded from the remaining analysis. Table 3 provides the correlations between the endogenous variables. Both TRUSTI (r = . 308, p = . 001) and TRUSTF (r = . 213, p = . 006) are significantly associated with REPORT. As such, the correlations indicate that greater trust in the external audit function is associated with a greater likelihood of reporting suspicious activity to the auditors.

| TENURE | FAMILIAR | REPORT | TRUSTI | TRUSTF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm tenure | |||||

| FAMILIAR | .042 | ||||

| REPORT | (.031) | .217** | |||

| TRUSTI | (.050) | .624*** | .308*** | ||

| TRUSTF | .111 | .279*** | .213** | .589*** |

- * p < . 05;

- ** p < . 01;

- *** p < . 001.

- FIRM TENURE: independent variable manipulated across two levels (low versus high); FAMILIAR: independent variable manipulated across two levels (does not know audit team versus knows audit team); REPORT: likelihood of reporting the observed wrongdoing; TRUSTF: reported trust in the audit firm; TRUSTI: reported trust in the individual auditor.

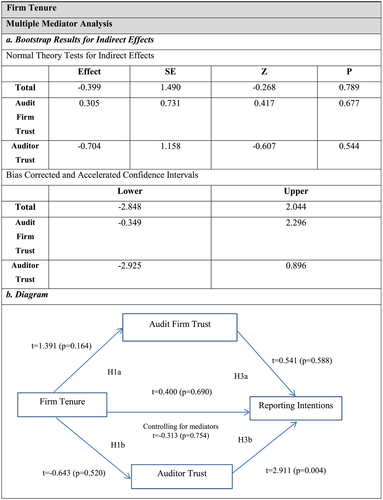

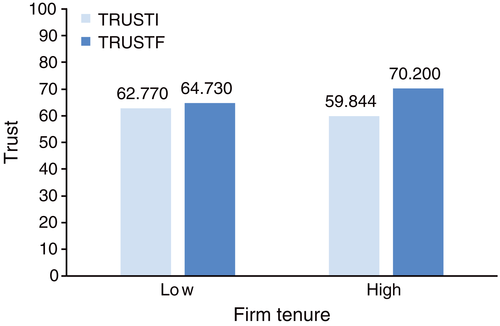

Table 4 illustrates the mean results by experimental condition for reporting intention, trust in the audit firm, and trust in the auditor. As shown in Figure 1, FIRM TENURE did not significantly impact REPORT (t = 0.400; p = . 690). However, there was a significant difference (see Figure 3) across the levels of FAMILIAR (t = − 2.823, p = . 005), with REPORT greater when the client had worked with the auditor in the past (M = 59.034) compared to when the client was not familiar with the individual auditor (M = 48.026). The results of TRUSTI and TRUSTF are discussed next in conjunction with the hypothesis tests.

| FAMILIAR | Firm tenure | N | REPORT | TRUSTI | TRUSTF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Does not know audit team | Low | 36 | 48.889 | 29.152 | 45.417 | 28.107 | 56.583 | 29.132 |

| High | 40 | 47.250 | 21.692 | 38.350 | 30.116 | 63.825 | 24.438 | |

| Total | 76 | 48.026 | 25.337 | 41.697 | 29.205 | 60.395 | 26.830 | |

| Knows audit team | Low | 38 | 60.421 | 25.839 | 79.210 | 14.688 | 72.447 | 22.017 |

| High | 50 | 57.980 | 23.685 | 77.040 | 15.677 | 75.300 | 19.465 | |

| Total | 88 | 59.034 | 24.523 | 77.977 | 15.210 | 74.068 | 20.532 | |

| Totals | Low | 74 | 54.811 | 27.920 | 62.770 | 27.881 | 64.730 | 26.764 |

| High | 90 | 53.211 | 23.320 | 59.844 | 30.108 | 70.200 | 22.432 | |

| Total | 164 | 53.933 | 25.430 | 61.165 | 29.073 | 67.732 | 24.556 | |

- REPORT: likelihood of reporting the observed wrongdoing; TRUSTF: reported trust in the audit firm; TRUSTI: reported trust in the individual auditor.

4.3 Hypothesis tests

The research question posed addresses the relationship between firm tenure and reporting intentions. The results displayed in Figure 1 suggest that the direct relationship between firm tenure and reporting intentions is not significant (t = 0.400, p = . 690).

Following Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) multiple-mediation method, audit firm trust (TRUSTF) and auditor trust (TRUSTI) were analyzed in a multiple-mediator analysis, with the results reported in Figures 1 and 3. For the firm tenure multi-mediation analysis (Figure 1) the normal theory tests for indirect effects indicated neither audit firm trust nor auditor trust were significant. Figure 2 displays the mean values for TRUSTF and TRUSTI for the various FIRM TENURE conditions. H1a states that audit firm tenure will positively impact the auditee's trust in the audit firm. FIRM TENURE (Low M = 64.730; High M = 70.200) did not have a significant relationship with TRUSTF (t = 1.391, p = . 164). As such, the results indicate that firm tenure is not associated with greater trust in the accounting firm. These results do not provide support for H1a.

H1b states that firm tenure will positively impact the auditee's trust in the individual auditor. In accordance with Figure 1, FIRM TENURE did not significantly impact TRUSTI (t = 0.643, p = . 520). As such, higher levels of firm tenure (Low M = 62.770; High M = 59.844) did not produce greater trust in the auditor. These results do not support H1b.

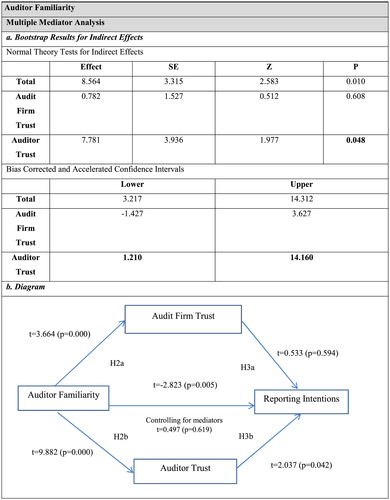

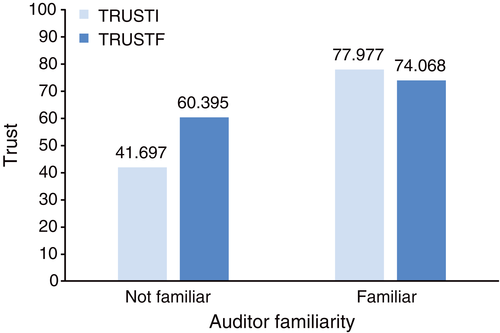

For the auditor familiarity multi-mediation analysis (Figure 3) the normal theory tests for indirect effects indicated only the indirect effect of auditor trust was significant (Z = 1.977, p = . 048). The bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals further indicate indirect effect of audit firm trust was positive and significant with a 95% confidence interval excluding zero (lower = 1.210; higher = 14.160). Figure 4 displays the mean values for TRUSTF and TRUSTI for the two auditor familiarity conditions.

H2a predicts that familiarity with the individual auditor will positively impact the auditee's trust in the audit firm. Auditor familiarity was positive and significant with TRUSTF (t = 3.664, p < . 001). As such, familiarity with the individual auditor (M = 74.068), in comparison with no familiarity with the individual auditor (M = 60.395), was associated with greater trust in the accounting firm. These results support H2a. H2b predicts that familiarity with the individual auditor will positively impact the auditee's trust in the individual auditor. As expected, auditor familiarity is positive and significant with TRUSTI (t = 9.882, p < . 001), and thus the client's experience with the individual auditors (M = 77.977) resulted in greater trust of the individual auditors in comparison with when the client had not worked with the individual auditor (M = 41.697). These results support H2b. Figures 1 and 3 also provide the multi-mediation results for REPORT when TRUSTF and TRUSTI are included.

H3a predicts that trust in the audit firm (TRUSTF) will have a positive relationship with an auditee reporting suspicious activity to the external auditor. H3a was not supported as there was not a significant positive relationship between TRUSTF and REPORT in the firm tenure model (t = 0.541, p = . 588; Figure 1) and in the auditor familiarity model (t = 0.533, p = . 594; Figure 3). H3b states that trust in the individual auditor (TRUSTI) will result in a greater likelihood of the auditee reporting suspicious activity to the external auditor. As anticipated, there is a significant positive relationship between TRUSTI and REPORT in the firm tenure model (t = 2.911, p = . 004; Figure 1) and in the auditor familiarity model (t = 2.037, p = . 042; Figure 3). The indirect effect of firm tenure on reporting intentions through auditor trust and firm tenure represents partial mediation because there is a direct effect of auditor familiarity on reporting intentions. The respondent's reporting intentions increase by 7.781 standard deviations for every one standard deviation increase in the firm tenure variable via its prior effects on respondent auditor trust and firm tenure.

Several supplemental tests were run that validated the robustness of the findings. The first was an examination of the multi-mediation model had the four original manipulations for firm tenure not been condensed to two conditions.10 Additionally, the data were split and analyses were performed separately for the samples with and without reported experience dealing with external auditors in the workplace (29% and 71% of the full sample respectively).11 A supplemental test was also run excluding the 4% of the sample with experience as an auditor.12

5 DISCUSSION

The results suggest that our two manipulations, firm tenure and familiarity, have differing impacts on some aspect of trust in the audit function as well as the likelihood that the auditee would report suspicious activity. While the correlations in Table 3 indicate that both trust in the individual and trust in the firm are significantly and positively associated with the intention to report, our multi-mediation analyses assert trust in the individual as the significant variable influencing the intention to report. This result stands in contrast to Seifert et al. (2014), who found that the likelihood of whistleblowing was higher for trust in the organization than for trust in the individual, though the difference was not significant. They surmise that both forms of trust are critical to improving propensity to report. However, as Seifert et al. (2014) explore these relationships within an organization, our results extend the importance of trust to the interorganizational context of the relationship between audit firms and their clients, and we believe that this contextual difference highlights the prominence of trust at the individual level, and in the case of this study, the relationship between the individual auditor and the client personnel. Collectively, our findings support the importance of trust as a construct in whistleblowing research, as suggested by Seifert et al. (2014).

Our mean comparisons by experimental conditions for reporting intentions indicate a significant difference across levels of auditor familiarity but not for firm tenure. Further, firm tenure resulted neither in greater trust in the accounting firm nor enhancement of the client's trust in the auditors performing the engagement. Conversely, familiarity with the individual auditors positively impacted trust in the firm, and, controlling for mediators, the resulting trust in the firm enhanced propensity to report. The results for the impact of familiarity are consistent with Gefen (2000), who indicated that familiarity creates a context that is necessary for the manifestation of trust. As such, the past working relationship between an individual auditor and a client employee establishes an appropriate structural foundation for enhanced transparency, and this mechanism is appropriately highlighted in our results.

The nonsignificant results for firm tenure were counter to our expectations, as we anticipated that, consistent with Cote and Latham (2006), the firm–client relationship would create a context in which all members of the organizational relationship achieve benefits due to reduced uncertainty, thus promoting a more transparent environment conducive to client reporting of critical issues. Importantly, though, our design distinguishes between the often-confounded constructs of firm tenure and auditor familiarity to offer a unique perspective on how these variables influence trust in the audit firm–audit client relationship. Conceptually, auditor familiarity and firm tenure can be associated with one another, in that a long firm tenure may result in the client personnel becoming more familiar with the individual auditors. This familiarity, of course, assumes some level of continuity among the individuals staffing the continuing auditor–client relationship. With these two variables appropriately disentangled, our results assert the significance of auditor familiarity in achieving positive outcomes for trust and reporting intentions. Ultimately, this study highlights the notion promoted by Mouzas et al. (2008, p. 1019): the “origin of trust lies in individuals.”

As such, the results of this exploratory study suggest that firm tenure, absent of consideration about engagement team dynamics, may not be effective at eliciting trust on an audit engagement unless that tenure is accompanied by familiarity with members of the audit engagement team. This finding is important, because firms do provide certain reputational benefits for auditors and audit engagements (Knechel et al., 2013), yet these benefits do not necessarily equate to a better level of trust between the individuals working on the different sides of the auditor–client relationship. Our findings indicate familiarity with the individual auditors is a critical ingredient in producing greater levels of trust, and this may be achieved by working toward keeping the composition of audit teams intact for continuing engagements, if feasible. The majority of audit fieldwork is conducted by junior-level auditors, and thus the relationships that these auditors build with the client personnel are crucial in establishing knowledge of the client. Given the levels of turnover facing the accounting profession (Herda, 2012), this level of familiarity is a major issue that likely impacts the quality of many audit engagements.

6 CONCLUSION

One of the arguments made against firm rotation proposals is the loss of institutional knowledge that will result from limiting audit terms. This argument has some merit because firms create a level of infrastructure on each audit client in terms of documentation of the client processes, and so on. However, as evidenced by the review of the audit firm rotation research and related papers presented herein, this argument has largely focused upon the firm, as an organization, and its level of involvement with the client, as an organization. Another part of the cultivation of institutional knowledge lies in the relationships developed with client personnel. Given the high turnover rates at public accounting firms, it is possible that these interpersonal relationships are constrained even with longer firm tenures because the makeup of audit teams changes frequently. The results of this study support this notion, and thus indicate that the continuity of engagement teams is a crucial aspect to retaining institutional knowledge and promoting audit quality.

This study is not without limitations. We encourage the reader to evaluate the results from the main analysis in light of the outcomes from alternative tests conducted and addressed in the footnotes. The relationship between firm tenure and the trust measures (i.e., H1a and H1b), nonsignificant in the main analysis, was significant under different combinations of firm tenure (see Endnotes 7 and 10). Specifically, with firm tenure varied across four lengths of time (new client, 2 years, 7 years, and 15 years), the relationship between firm tenure and both trust in the firm (H1a) and the individual auditor (H1b) was significant. Similarly, when tenure was analyzed across three conditions, with the 2-year and 7-year lengths combined, trust in the firm (H1a) was positively associated with the tenure of the firm. While these results differ from the main analysis, where firm tenure was dichotomized (new client/2 years versus 7 years/15 years), we believe that our approach in the main analysis provides the optimal representation of the results, not only because it attempts to address the relative tenure lengths proposed by European Union regulators in recent years, but also because (1) it errs on the side of not supporting H1a and H1b, and (2) the results for auditor familiarity (H2a and H2b), a key contribution of this study, are robust across each alternative test. The impact of firm tenure, admittedly, comes with mixed results when viewed from the lens of the alternative tests, and future researchers should continue to understand the implications of firm tenure in the auditor–client relationship. Ultimately, though, the study strongly asserts familiarity as a critical variable in examinations of engagement dynamics and audit quality outcomes.

Furthermore, some key limitations from this study highlight significant opportunities for future research. First, the study was conducted in an experimental setting, and the manipulations studied in isolation ignore other factors that could be relevant in the auditor–client relationship. Future research should examine these issues in different settings to add to the results obtained in this study. Second, subjects were recruited through Amazon's MTurk system. While this mechanism allowed for the recruitment of subjects who met certain criteria and who could serve in the capacity of entry-level client employees, the nature of the online data collection resulted in less control over the experimental setting in comparison with a face-to-face collection; hence, future studies might explore these questions in an in-person context. Third, this examination focused upon the issue of trust at the junior level of the auditor–client relationship. The typical progression for individuals in an audit firm has the junior level auditor moving up to oversight responsibilities and new individuals joining the team. However, the trust issue is likely salient at all levels, including the interactions between partner-level professionals and executive management. Future research should examine the trust variable at several different levels in order to further the study of trust in the auditor–client relationship. Additionally, our experimental design did not allow us to consider the influence of auditor firm tenure on auditor familiarity, as each of these variables was manipulated in our research instrument. As an extension to this study, future research should examine how the relationship between these two variables impacts the outcomes of trust and intentions to report fraud. Furthermore, while our study considered the impact of familiarity on trust, we did not specifically consider the joint effect of familiarity and trust on reporting intentions. Given the discussion from Gefen (2000) about the interaction between familiarity and trust, the literature would be enhanced by future research that aims to manipulate not only familiarity, but also levels of trust (high versus low) in an experimental setting. Finally, AICPA identifies familiarity as a potential threat; as such, excessive familiarity could adversely affect the performance of the audit team. Future research could explore the association between audit team continuity and audit quality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank participants at the 10th annual BYU Accounting Research Symposium for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript. We acknowledge Ohio University, University of Montana, and Washington State University for their research support.

ENDNOTES

- 1 Internal audit and management review were credited as the second and third most frequent sources of initial fraud detection, accounting for 16.5% and 13.4% respectively (ACFE, 2016).

- 2 Several research studies have recommended using a HIT approval rate of 95% or greater (Berinsky, Huber, & Lenz, 2012; Chandler, Paolacci, & Mueller, 2013; Goodman et al., 2013; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010; Peer et al., 2014). The HIT approval requirement of 1000 or more approved HITs was designed to have a meaningful base to determine the 95% HIT approval rate.

- 3 Similar to Seifert et al. (2014), Kaplan and colleagues explore impact on propensity to whistleblow in an intraorganizational context. For example, Kaplan et al. (2015) examine the effect of management safeguards and management likeability within an organization on the propensity to report fraud.

- 4 The information provided to participants described a hypothetical situation and then placed a fictitious employee in the position of discovering a fraudulent situation. The method of describing a hypothetical scenario depicting a third party has been successfully implemented in recent reporting intention literature (Kaplan et al., 2009, 2011, 2015; Kaplan, Pope, & Samuels, 2010; Kaplan & Schultz, 2007). This method has been adopted to help address concerns related to social desirability bias, which may impact the results if measured first person (Chung & Monroe, 2003).

- 5 All procedures performed in this study involving human subject participants were in accordance with the standards of the Institutional Review Board of each institution.

- 6 It was noted that the mean values of reporting intentions for the firm tenure conditions were examined and it was determined that there was not a significant difference between 2 years (.M = 52.613.) and 7 years (.M = 55.203.) (.t = − 0.640., .p = . 524.).

- 7 The multi-mediation analysis performed and reported in Figures 1 and 3 was also evaluated using a three firm-tenure-length manipulation (combining 2 years and 7 years). In this analysis, it was noted that the only difference is that H1a becomes significant. We determined to stay with the sample having only two firm-tenure conditions as the original regulation proposal suggested 6 years and the final regulation in place identifies 10 years as a significant length. We felt that combining 7 and 15 years was more appropriate given the time frames discussed by regulators while crafting the tenure requirements.

- 8 The manipulations presented a challenge because the crossed design resulted in one particular cell where FIRM TENURE was NEW, yet the client employee was familiar with the individual auditors. In this scenario, the subjects were informed that the client employee met the individual's auditors while working at a previous job. Though not representing what historically has been traditional career paths, Rigoni and Adkins (2016) present a Gallup poll that indicates millennials (those born between 1980 and 1996) are “job hoppers” and change jobs at a rate three times greater than previous generations; hence, the scenario described in this cell may be considered more plausible now than in the past.

- 9 The multi-mediation analysis performed and reported in Figures 1 and 3 was also run with the full sample (.n = 235.). In the analysis of the full sample, it was noted that the only difference is that H1a becomes significant. We determined to stay with the sample having the manipulation checks removed, as the sample represents a more conservative approach and in light of the significant results identified as not changing.

- 10 When examining the findings with the original four conditions for firm tenure serving as the independent variable in place of the two firm-tenure conditions used in the main analysis, H1a and H1b become significant. In addition, the mediating relationship of auditor trust becomes significant. While H1a and H1b are supported in this analysis, we highlight the mixed findings obtained and documented in the full text of the paper. As there was not a significant difference between the first two and last two firm-tenure conditions, we feel that it is appropriate to combine those respective conditions, which allows for a more conservative analysis of the data.

- 11 Mixed findings were observed when the data were split and analyses were performed separately for the samples with and without reported experience dealing with external auditors in the workplace. This is likely driven by the difference in sample size. For the analysis of the sample that included participants without experience with an auditor, the results were consistent when evaluating both auditor familiarity and firm tenure (.n = 111.). When evaluating the participants with experience with an auditor, H3a becomes significant and H3b becomes nonsignificant when evaluating both firm tenure and auditor familiarity (.n = 53.). In the case of participants with auditor experience, the number of participants is likely too small to provide sufficient power to adequately perform a robust analysis.

- 12 When examining the findings of the analysis that excluded the 4% of the sample with experience as an auditor, the findings were consistent when evaluating both auditor familiarity and firm tenure.

APPENDIX A

Case

*,** In the scenarios that follow, the italicized text indicates which wording was substituted in the scenario variations, manipulating firm tenure (shown in parentheses) and auditor familiarity. The wording was not italicized in the research instrument, nor were there parentheses. All other wording remained the same.

Background

Alabaster is a mid-sized public company located a short distance outside of Chicago, IL, and produces several components used by the automotive industry. Business has been slow but is steadily growing. This year's earnings are expected to be the best in the past five years. As a public company, Alabaster requires an annual audit to comply with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The company's external audit firm typically contacts various individuals throughout the company to better understand their job responsibilities, discuss the process involved in performing their work, and evaluate any related controls. The contact also involves the external audit firm identifying areas that can be sensitive, especially if there is a need to discuss confidential information. In the scenarios that follow, you are to assume the employee of Alabaster feels Alabaster is a reliable organization. You are further to assume that the employee of the external audit firm also feels his/her organization, the audit firm, is trustworthy.

Scenario 1a: new audit firm/new auditor

Sam Lee has been working in the Sales department of Alabaster for two years (but is still the newest member of the department), and has been interviewed on each of the last two audits. An email was recently sent out indicating that Alabaster will be using a new external audit firm this year.*

Sam knows the company has been struggling to make sales and that management is worried about not making earnings. One afternoon while Sam was leaving the break room, he overhears part of a conversation involving John Simon who works a few cubicles down from himself. Like Sam, John is an entry-level employee.

Sam cannot help but overhear part of John's conversation. As he listens, Sam hears John say, “Don’t worry. No one will realize that we are shipping goods to customers that have not been ordered. We can record the revenue as if it met all the criteria for revenue recognition and meet our quarterly earnings estimate. No one will know the difference. Just make up a purchase order for a new company and send it to me. I will approve it for shipment.”

Sam is not sure what to think. During his annual training, he was told of situations of financial statement fraud where people inflate the actual results of the company. Later that month Sam is contacted by a member of the new external audit firm, who asked to discuss the sales process and the controls the department has in place to authorize new customers and related sales. In prior audits, Sam and the auditors from the previous firm have chatted at length about both Sam's job responsibilities and things other than work, such as sports and the economy. However, this is a new audit firm and Sam has never talked to this new auditor.**

Scenario 1b, 1c, and 1d: 2-, 7-, or 15-year audit firm tenure/new auditor

An email was recently sent out indicating that Alabaster will continue with the accounting firm that has performed the annual audit for these past two (seven, fifteen) years.*

Sam knows that Alabaster has had a relationship with this audit firm for the past two (seven, fifteen) years and has himself interacted and been interviewed by the same people in the last two audits. In prior audits, Sam and auditors have chatted at length about both Sam's job responsibilities and things other than work, such as sports and the economy. However, Sam has never talked to this new auditor.**

Scenario 2a: new firm/auditee knows auditor

An email was recently sent out indicating that Alabaster will be using a new external audit firm this year.*

Sam and the auditor both realized they knew each other from prior places of employment. Prior to coming to work at Alabaster, Sam had worked at another company and had been interviewed two years in a row by this person who, at that time, worked for a different auditing firm. As he recalled the prior audits, Sam and the auditor chatted at length about both Sam's job responsibilities and things other than work, such as sports and the economy.**

Scenario 2b, 2c and 2d: 2-, 7-, or 15-year audit firm tenure/auditee knows auditor

An email was recently sent out indicating that Alabaster will continue with the accounting firm that has performed the annual audit for these past two (seven, fifteen) years.*

Sam knows that Alabaster has had a relationship with this audit firm for the past two (seven, fifteen) years. He has been interviewed by the same people in the last two audits and these auditors will be interviewing him again this year. In prior audits, Sam and the auditors have chatted at length about both Sam's job responsibilities and things other than work, such as sports and the economy.**

What is the probability that Sam (company employee) will report John's conversation to the external audit firm?

(Please indicate your response by circling one of the below percentages)

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

Based on the employee's past and present experience, how would you characterize the level of trust the employee has with this auditor?

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No trust | Some distrust | More consistent trust | Complete trust | |||||||

Based on the employee's past and present experience, how would you characterize the level of trust the employee has with this audit firm?

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No trust | Some distrust | More consistent trust | Complete trust | |||||||

Biographies

Aaron B. Wilson, PhD, CPA, CFE, CGMA, is an assistant professor of accounting at Ohio University. He conducts behavioral audit research involving whistleblowing incentives and behavior, auditor litigation, and nonprofit governance.

Casey McNellis, PhD, CPA, is an assistant professor of accounting at Gonzaga University. He primarily conducts behavioral audit research on a variety of audit issues, including auditor litigation and auditor performance. He also enjoys writing instructional case studies on various financial accounting and auditing topics.

Claire Kamm Latham, PhD, CPA, CFE, is an associate professor of accounting in the Department of Accounting at Washington State University Vancouver. She conducts empirical and behavioral audit research involving trust, audit quality, and ethics and the public accountant. Dr Latham has published in numerous journals, including the Journal of Business Ethics, The Journal of Forensic Accounting: Auditing, Fraud, and Taxation, Issues in Accounting Education, Advances in Accounting Education, Advances in Behavioral Accounting Research, and the Journal of Accounting Literature.