Support for family caregivers: A scoping review of family physician’s perspectives on their role in supporting family caregivers

Funding information

This research was supported by a grant from the Northern Alberta Academic Family Medicine Fund.

What is known about this topic

- Family caregiving has become more onerous in the last two decades.

- Family physicians have the potential to reach the majority of caregivers throughout the care trajectory.

- The demand for primary care to support caregivers comes primarily from researchers or advocacy organisations.

What this paper adds

- There is little literature on family physicians’ perspectives on their roles in supporting family caregivers.

- Collaborative integrated primary care models are recommended as the most feasible model for supporting family caregivers.

- Research to understand family physicians’ perspectives of their role in supporting family caregivers is warranted.

1 BACKGROUND

Caring takes a toll on family caregivers throughout the care trajectory (Steppacher & Kissler, 2018). Family caregivers often report worsening health and stress/distress (Bauer & Sousa-Poza, 2015; Richardson, Lee, Berg-Weger, & Grossberg, 2013). Family caregiving has become more onerous as illness, frailty and impairments become more severe, but in the last two decades medical advances, increased longevity, shorter hospital stays and the push for community care have made caregiving even more complex and longer lasting (Health Quality Ontario, 2016; Schulz et al., 2018; Sinha, 2018). In 2016, over a third (34%) of caregivers to long-term home care clients in Canada were stressed and distressed (Health Quality Ontario, 2016), up from 16.6% in 2010 (Canadian Institutes for Health Information [CIHI], 2010). Furthermore, primary family caregivers at the greatest risk of distress are those who live with the care recipient, provide more than 20 hr of care, care for a person with moderate to severe impairments (functional, cognitive) and/or depression, and coordinate care or provide medical treatments (Pauley, Chang, Wojtak, Seddon, & Hirdes, 2018; Sinn et al., 2018).

Given that primary care physicians have the potential to reach the majority of caregivers throughout the care trajectory (Pindus et al., 2016), an opportunity exists for caregivers to benefit from care and support from primary care teams (Afram, Verbeek, Bleijlevens, & Hamers, 2015; Richardson et al., 2013). Primary care is credited for better population health, more health equity and better use of resources (Starfield, 2012). Four key domains are associated with high-quality primary care: first-contact access for each need, person focused (not disease) over time, comprehensiveness and coordination of care (Hochman & Asch, 2017). Vulnerable populations benefit most from quality primary care (Starfield, 2012) and family caregivers are a vulnerable population (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2018). They have high rates of stress and depression, impaired ability to recover from an illness and often neglect their own health because they are providing care. In fact, caregiver's poor health or mortality is frequently the reason for the client's LTC admission (CDC, 2018). Family caregivers believe family physicians are well positioned to support them (Brotman & Yaffe, 1994). Indeed, family physicians were the only sources of formal support associated with reduction of burden for family caregivers of long-term care clients (Shiba, Kondo, & Kondo, 2016).

However, primary care physicians may regard supporting caregivers as outside the purview of their role. In Australia, Bulsara and Fynn (2006) found physicians saw their role as to the patient only. As such, they were unable or unwilling to provide emotional or psychological support for caregivers. However, the vast majority of physicians (96%) did think they had a role in referring caregivers to services. Similarly, 91% of Canadian family physicians (n = 142) believed they could only respond to the non-medical needs of caregivers as they were not the patient (Yaffe & Klvana, 2002). Over 80% of physicians in this same study reported that interactions with caregivers were stressful and three-quarters (75.5%) believed they were not adequately remunerated for the stress and time involved to meet caregivers needs. Similarly, general practitioners in the United Kingdom (n = 211) found they lacked the time, resources and training to meet caregivers needs (Simon & Kendrick, 2001). These results suggest that the existing primary care system needs to be adapted to support family caregivers.

The demand for system changes to support caregivers primarily comes from bottom-up pressure from academic researchers or top-down in glossy reports from national or provincial agencies (Byrne, 2016). For example, Romanow (2002) in Building on Values: The Future of Healthcare in Canada and Schulz and Eden (2016) Families Caring for an Aging America both recommend that health systems should support caregivers. In addition, editorials and think pieces theorise that primary care should play a central role in caregiver support (Collins & Swartz, 2011; Frisch, 2013; Massoud, Lysy, & Bergman, 2010; Schulz & Czaja, 2018), but primary care is a complex system. Practices are already stretched by growing workloads and decreasing resources (Okunogbe et al., 2018; Steinglass, 2006). Yet, the perspective of primary care physicians is essential to meaningful health system change (Pawson, Greenhalgh, Brennan, & Glidewell, 2014). As such, an important question to ask is: What do primary care physicians think about supporting caregivers? We conducted a scoping review to understand what is known about support for caregivers in primary care by family physicians.

2 METHODS

The initial literature search of the interface between family physicians or primary care and family caregivers revealed numerous studies on caregivers’ perceptions of interactions with physicians, but only a limited number on physicians’ perceptions on supporting family caregivers. Hence, we decided to do a scoping review to enable a broader exploration of what is known about the topic at hand rather than a systematic review/detailed analysis of a specific research question. A scoping review summarises and synthesises the extent, range and nature of the literature to inform research, practice, programmes and policy by mapping key concepts, types of evidence and gaps in a defined field (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brien, 2010).

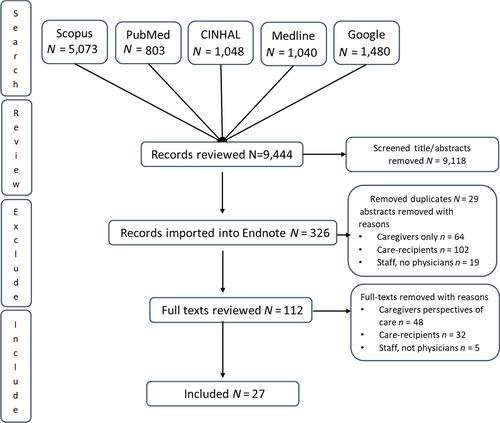

We followed Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) protocols for scoping reviews and Thomas and Harden (2008) guidance for thematic synthesis. We restricted the search to English language and to the last decade (2009–2019) in the electronic databases Scopus, Medline, PubMed and CINAHL using the search terms related to physicians and family caregivers (see Table 1 for search terms). We searched for grey literature on Google using the same terms and Google's search guidance (Google, ND; see Table 1 for search terms and strategy). We sought a broad range of literature, including original research, review articles, systematic reviews, international, national and provincial reports, conceptual/theoretical papers and opinion papers that explored physicians’ perspectives on caregiver support or provided context on physician's role in caregiver support (see Figure 1).

|

Conducted title, abstract and subject headings search for terms related to Physicians: ‘primary care’ OR ‘family care’ AND physician OR doctor OR ‘general practitioner’ OR ‘primary care Physician’ OR ‘family physician’ OR ‘medical home’ AND Family caregivers: Caregiver OR carer OR ‘family caregiver’ OR ‘unpaid caregiver’ OR ‘informal caregiver’ Limited to years: 2009–2019 Title, Abstract and Subject Heading searches were adapted for databases. *Boolean search: Title (Intitle), Abstract (InAB), Subject Heading (InSW) |

We excluded literature that included only patients, caregivers or staff perceptions of physician's care or primary care physician's roles. In the initial keyword searches, we screened titles and abstracts for inclusion and inclusion criteria. The search results were imported into EndNote and duplicates removed (see Figure 1). Full texts of titles and abstracts remaining after duplicates were removed were retrieved and read in their entirety by the second author. The first and second authors reviewed the included and excluded articles and agreed on the final articles to be included (n = 27). Their results and findings were entered into an extraction table (Table 2). As recommended by Arksey and O’ Malley's (2005) scoping review protocol, we did not assess quality.

| Author, Year | Methodology; Health condition; Country; Physicians # | Aim | Research gap | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedard et al. (2014) | Qualitative survey development; Dementia; Canada; N = 9; Urban n = 6; Rural n = 3 | Develop a survey for family physicians to better understand family physicians’ beliefs, level of knowledge and sense of accountability regarding their support of informal (e.g. unpaid) caregivers of older adults | Limited knowledge of caregiving issues/support from perspective of family physicians | Most physicians reported they do not have enough time to interact with caregivers and were not adequately reimbursed for supporting caregivers. It would be useful for health planning to collect survey data on physicians’ perspectives about caregiver interactions |

| Bernard and Yaffe (2014) | Commentary; Family caregiver; Canada; n = NA | What is the physician's responsibility to a patient's family caregiver? | Support to caregivers raises ethical issues about patient confidentiality | It is appropriate for health professionals to argue against patient's choices when patient's exercise of autonomy comes at too great a cot to their families. Physicians should view helping families sort out balance of interests as one of their ethical responsibilities. |

| Burridge et al. (2017) | Qualitative; Advanced Cancer; Australia; N = 5 | Needs Assessment Tool for Caregivers (NAT-C) was developed for carers to self-complete and use as the basis of a General Practitioner [GP] consultation, then tested in a randomised controlled trial. This paper reports a qualitative research study to determine the usefulness and acceptability of the NAT-C in the Australian primary care setting. | Caregivers do not tell family physicians about their needs | The support available to carers of cancer patients from the health professionals with whom they have the most contact may or may not be adequate. The support available through GPs maybe overlooked. Carers may not recognise that discussing their needs with their GP is legitimate. Although a checklist to help carers and GPs to talk, supportive consultations take time. This raises questions about organisational issues to be addressed so carers seek and benefit from GP support. |

| Burridge et al. (2011) | Qualitative, Advanced Cancer; Australia; N = 13; GP n = 6; Cancer consultants n = 7 | Investigate the norms, assumptions and subtleties which govern caregiver–general practitioner [GP] consultations and explores factors affecting their interactions regarding caregivers’ own health concerns | GPs rely on patients to raise concerns but caregivers as patients may be disinclined to cue their GP | Caregivers may not raise their health concerns with GPs, so it is up to GPs to prompt them to do so. GPs may not have the desire or capacity to engage with caregivers, but the potential difference GPs can make to caregiver's health is substantial. GPs require high-level communication skills and commitment to find new ways to engage caregivers as patients proactively. |

| Carduff et al., 2014 | Qualitative; End-of-life; UK; N = 2 | Explore the barriers to, and consider strategies for, identifying carers in primary care. | Carers are largely unsupported by health and social care services. | Ambiguity about whose role is to identify & support carers. Carers do not identify as a being a carer, preferring to think of themselves as a spouse, son, daughter. Primary care lacks knowledge of services available. Physicians were concerned with opening Pandora's box demand for services that may not be available and lack of time and resources. |

| Doctors of BC (2016a) | Policy paper; Family caregivers; Canada; n = NA | Physicians and government can play leading roles to support caregivers. Physicians consider themselves as partner in care, including caregivers in patient care planning and implementation wherever possible. | Consideration of caregiver needs is required in healthcare and social service planning and provision. | Doctors of BC have committed to working with the BC government and stakeholders to develop a strategy to formally recognise caregivers as a key partner in healthcare delivery and to establish principles that require the consideration of caregiver needs in health and social service planning and provision. |

| Doctors of BC (2016b) | Action guide for family doctors; family caregivers; Canada; n = NA | Guide to organising physicians’ practices to support family caregivers. | Need guidance on practices with caregivers. | 4 Steps: Identifying caregivers, involving caregivers in patient care; monitoring the health of caregivers; and providing information and support to caregivers. |

| Doekhie et al. (2018) | Qualitative; chronically ill elderly; Netherlands; N = 6 | Explores different perspectives of patients, informal caregivers and primary care professionals on involvement in primary care team interactions. | Patient/caregiver involvement is an important element of person-centred primary care. | Caregiver involvement is shaped by professionals whose perspectives of involvement may diverge. GPs over 50 felt they need to take a steering role. There are conflicting ideas about roles on team and caregiver's inclusion. Professionals’ responsibility to the patient is hindered by dominant caregivers who have opposing or deviating expectations from the patient. |

| Foley et al. (2017) | Qualitative; Dementia; Ireland; n = 14 (GPs) | Explore GP’s dementia care, educational needs to inform the design and delivery of an educational programme for GPs. | GPs are challenged by dementia care and have identified it as an area for further training. | GPs expressed a wish for further education through small group workshops. GPs believe carers need GPs support, but have limited time. |

| Gill et al., 2014 | Qualitative, Multimorbidity, Canada; N = Not reported | Explored the care challenges of older patients with multimorbidity, their informal caregivers and family physicians. | Policy reform requires understanding of the patient's core team. | Physicians are frustrated by poor communication between providers, long wait times for appointments and how to provide care to patient and caregiver when situation extended beyond their clinical role. There are few clinical guidelines available to family physicians to manage multimorbidity nor for co-management by patients, caregivers and physicians. |

| Gitlin and Hodgson (2016) | Literature review; Ethics of working with caregivers; US; N = NA | Examine whether health and human services professionals have a moral obligation to assess and address the needs of family caregivers and if so the challenges in doing so under current healthcare and reimbursement mechanisms. | Physicians’ moral distress and uncertainty over the dilemma to support caregivers. | It is unethical not to reach out to family caregivers. The ethical dimensions of providing care to patients with dementia & caregivers are rarely discussed. Physician's moral distress in treating caregivers is due to the restrictive context of healthcare delivery and focus on patient. The health system is not dementia ready. |

| Greenwood et al. (2011) | Qualitative; Stroke; UK; N = 5 (GPs) | Explores both the support stroke carers would like from general practice and their reactions to the community-based support proposed in the New Deal. Second, perceptions of a general practice team are investigated covering similar topics to carer interviews but from their perspective. | Perspective of support carers need/provided. | GP teams are valuable in supporting stroke survivors and carers. Research is needed to determine general practice teams’ awareness & identification of carers and the difficulty they encounter supporting carers. Carer policy initiatives need greater specificity and attention to carers and carer's diversity. |

| Greenwood et al. (2010) | Quantitative; any condition; UK; N = 78 | Identify general practitioners’ attitudes, awareness of issues, and knowledge of carers’ issues, and perceptions of barriers and enablers to provision of services. | General practice is the first point of contact for support. | GPs recognise they have an important role supporting carers but would like training and support. Further investigation is needed to determine how to train and facilitate GPs and their practice teams to support carers. Identifying carer's champions among practice staff is a possible way forward |

| Hum et al. (2014) | Qualitative Dementia; Canada; N = 13, family physicians n = 6 and specialists n = 6 | Explored the perceived roles and attitudes towards dementia care from the perspectives of family physicians and specialists. | Assessment and ongoing management of dementia falls largely on family physicians. There is little research on physicians’ expectations that are of their role. | Shared and collaborative care can optimise delivery. Patient caregiver education & support deemed essential, most physicians recognised this was difficult and thought non-physician members of multidisciplinary teams could effectively carry out this role. Community resources are fragmented and difficult to access. |

| Jones et al. (2012) | Quantitative; any condition; UK; N = 95 81% pre-workshop questionnaire, 94% post-workshop and 52% 3 months post | Attitudes towards and knowledge of carers by GPs and other primary care workers and changes over time of. | Did education change GP’s attitudes and practices towards caregivers? | GPs and primary care teams saw primary care as having a significant role in directly assisting carers especially with emotional support & referral to other services. However, there was lack of knowledge about carers’ issues, limited confidence in assisting carers and few services within primary care teams focused on carers. Formal carer training workshops (delivered by GP and carer) had a positive impact on GPs and primary care team. |

| Leu et al. (2018) | Quantitative; any condition; Switzerland; N = 4 | Professionals’ awareness of young caregivers and the practice tools necessary to support young carers. | Young caregivers remain unrecognised. | Professionals have low level of awareness of young carers but highlight professionals’ willingness to engage with young carers. They wanted tools to help them identify this group and ensure they receive appropriate support. |

| Kiceniuk et al. (ND) | Qualitative, Dementia, Canada; Family medicine and specialists n = 10 | Generate knowledge about the issues concerning primary healthcare and support for caregivers of individuals with dementia | Need foundation to create model of shared care. | Caregivers do not access the variety of available health & support services. Physician remuneration created a barrier to providing care. They are unable to bill for caregivers unless the caregiver is their patient and books an appointment for themselves. Caregivers do not identify, nor do they recognise their need for support. Improve care provider education on caregiver needs and dementia. Improve links between family physicians and available caregiver resources. |

| Krug et al. (2018) | Qualitative, End-of-life; Germany; N = 19 | Identify potential intervention targets, this study deals with the challenges general practice providers face. | Need to know the barriers providers face in supporting family caregivers. | General practice professionals play important role in establishing contacts and coordinating care. Practice teams perceive themselves as critical role in supporting carers, but it is insufficient to demand a professional support network; existing structures need to be recognised and included into care. |

| Mitnick et al. (2010) | Review; Ethics of working with caregivers; United States; N = NA | Ethical guidance to physicians in developing mutually supportive patient, caregiver, physician relationships. | Physicians face ethical challenges in partnering with family caregivers. | The focus should remain on the patient. Physicians should validate the caregiver's role and be sensitive to commitments the caregiver may have regarding how he/she will manage care. Physicians should develop patient- and caregiver-specific plans and provide information, training and referrals to support those plans |

| Moore et al. (2018) | Commentary, Dementia; Canada; N = NA | Article developed in conjunction with College of Family Physicians of Canada Care of the Elderly committee describes family physician's role in key aspects of dementia care. | Dementia care in Canada is characterised by fragmentation of care across sectors, inadequate specialists caring for persons with dementia and lack of a national dementia strategy. | Family physicians should consider solutions to individuals’ and caregivers’ problems across the stages and transitions of dementia. Family physicians evaluate strain on caregivers and facilitate a diversity of services to decrease burden, improve quality of life and enable caregivers to provide at home care. Family physicians refer patients and families and caregivers to community service organisations for information, support and education about dementia; and, caregiver support and respite. |

| O'Connor (2011) | Review; Dementia; Ireland; N = NA | Assess to the role of general practitioners in Ireland caring for dementia carers. | The Action Plan for Dementia (1999) emphasised general practitioners were the ‘critical agents in the process of care’. A 2007 report by the Alzheimer's Society of Ireland showed few of these recommendations had been implemented. | Carers want GPs to educate them and look beyond the medical needs of the patient. They felt GPs were unaware of their personal needs and worries. GPs are reluctant to get involved in caring for dementia patients and carers citing lack of professional competency, belief that little can be done and the dearth of resources to support them in their role. GPs in Ireland should be vigilant for adverse health outcomes in carers not only while providing care at home but also after the patient is institutionalised. |

| Princess Royal Trust (2011); Royal College of General Practitioners | Action Guide for General Practitioners; UK; N = NA | GPs are the first point of contact which is why they play an invaluable role in the daily lives of carers. | Many carers go unidentified until many years into their caring role. | 6 Step Action plan: Identifying a carers lead in practice, identifying carers, involving carers in patient care, improving healthcare for carers, providing information and support to carers, and auditing and improving carer support. |

| Robinson et al. (2010) | Narrative Literature review; dementia; N = NA | Narrative review of role of primary care physicians in long-term care of people with dementia living at home. | Updated to align with NICE/SCIE guidelines. | Support for carers of people with dementia is a theme. Primary care physicians should endeavour to provide proactive care support and to monitor their health and well-being in addition to caring for the person with dementia. |

| Skufca (2019) American Association of Retired Persons | Survey; Family caregivers; US; physicians N = 267 (nurse practitioners/physician assistants n = 133) | Primary care providers’ experiences with family caregivers. | Lack knowledge of primary care providers’ perception of their experiences with family caregivers. | Primary care providers are interested in working with caregivers. They believe knowledge sharing with caregiver results in better patient outcomes and higher satisfaction. They are interested in working more with caregivers in the future. Provider/caregiver interactions focus on medical tasks – managing medications, arranging services, performing medical tasks. Identifying the primary family caregiver could improve communication. In office, materials are perceived as the most impactful caregiver resource. Time constraints are a key barrier. |

| Sunne and Huntington (2017) | Literature review. Dementia; US | Review the role of primary care physician tackling the care of the dementia caregiver. | Concise review on how to care for caregivers is needed. | Caregivers’ well-being is often overlooked and undertreated. The most feasible support model is collaborative care model that includes physician, case manager and community support organisations. |

| Thyrian and Hoffman (2012) | Quantitative survey; Dementia; Germany; n = 335 | Understand GP’s workload and opinions regarding areas for improvement in dementia care. | Little is known about GP’s dementia care delivery. | GPs recommend spending a lot more time with patients and caregivers and providing better support to increase their social participation. They recommend abolishing a healthcare budgeting system that economists think is necessary to control healthcare costs. |

| Wang et al. (2018) | Qualitative; Dementia; China; N = 20 | Clarify needs of informal caregivers and barriers of primary care workers towards dementia care management in primary care. | Need to improve care and services to people with dementia and their caregivers. | Primary care is positioned to manage dementia care, but heavy workloads prevent management. A community-based team model should be established. |

2.1 Data analysis

We imported the papers into NVivo for data management. We coded the text in three stages: line-by-line, for descriptive themes, and then generated analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, 2008). In line-by-line coding, we began adding conceptual codes that would ‘translate’ the content from one study to another. The first and second authors began collating the initial codes into descriptive themes in the second stage. We developed these themes by staying close to the primary studies. We checked back and forth to ensure that the themes reflected the intent within and across the primary studies. Lastly, we identified the key points within these themes through examining the coding frequencies and discussing the storylines in the themes.

3 RESULTS

In all, 27 studies met the broad criteria we set for this 10-year scoping review. In total, 23 papers were from the peer-reviewed literature and four published by associations in the grey literature. Peer-reviewed literature included the following: three papers reviewing the ethics of physicians engagement with caregivers (Barnard & Yaffe, 2014; Gitlin & Hodgson, 2016; Mitnick, Leffler, & Hood, 2010); three literature reviews on the role of physicians in care of the dementia caregivers (O'Connor, 2011; Robinson et al., 2011; Sunne & Huntington, 2017); a report on the development of a survey on physician's perceptions of care for caregivers (Bedard, Gibbons, Lambert-Belanger, & Riendeau, 2014), a policy paper (Moore, Frank, & Chambers, 2018), 12 qualitative investigations (Burridge, Mitchell, Jiwa, & Girgis, 2017; Burridge, Mitchell, Jiwa, & Girgis, 2011; Carduff et al., 2014; Doekhie, Strating, Buljac-Samardzic, Bovenkamp, & Paauwe, 2018; Foley, Boyle, Jennings, & Smithson, 2017; Gill et al., 2014; Greenwood, Mackenzie, Harris, Fenton, & Cloud, 2011; Hum et al., 2014; Kiceniuk et al., ND; Krug et al., 2018; Leu, Frech, & Jung, 2018; Wang et al., 2018); and three reports on two surveys (Greenwood, MacKenzie, Habibi, Atkins, & Jones, 2010; Jones, Mackenzie, Greenwood, Atkins, & Habibi, 2012; Thyrian & Hoffmann, 2012). A policy paper Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b), two guides to developing caregiver-centred care practice (Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Princess Royal Trust, 2011), and a survey (Skufca, 2019) were published by organisations.

In all, 16 primary studies sought physicians’ perspectives with 800 physician informants overall (range = 2–335; mean = 53, median = 13). One study did not report on the number of physicians participating (Gill et al., 2014). The papers were, in order of number of papers, from Canada (n = 8), the United Kingdom (n = 6), the United States (n = 4), Australia (n = 2); Ireland (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1) and China (n = 1). More detailed characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 2.

We defined three main themes: (a) Primary care is the ideal context for reaching most caregivers and overwhelming recognition that caregivers would benefit from support; (b) collaborative, integrated care models were the recommended designs for caregiver-centred care practices and (c) actualising consistent support for caregivers within primary care practices remains elusive. Therefore, we identified the facilitators and barriers to caregiver-centred care at the practice, health system and policy levels. We delineate the subthemes from these main themes in the sections that follow.

3.1 Primary care is the ideal context for reaching most caregivers

Authors recognised that family caregivers need support and thought that primary care is the ideal context for reaching caregivers (all included papers). Typically, primary care is the earliest point of contact making it potentially a valuable resource for reaching the most caregivers. The primary care physician's involvement in supporting family caregivers could improve outcomes such as caregiver health, better care for the care recipient and satisfaction with care.

However, there is ambiguity about the physician's role in supporting family caregivers, particularly if the caregiver was accompanying the patient. For example, Burridge et al. (2011) reported that in cancer treatment both family physicians and caregivers thought that discussing family caregivers’ needs was not legitimate when the patient was so ill. Carduff et al. (2014) also reported ambiguity because doctors were reactive rather than proactive. Doctors expected caregivers to ask if they needed support.

The three ethical reviewers blamed this ambiguity on restrictive health delivery contexts that focus on the patient and patient confidentiality (Barnard & Yaffe, 2014; Gitlin & Hodgson, 2016; Mitnick et al., 2010). All recommended that the focus remain on the patient but stated that physicians do have an ethical responsibility to family caregivers. Gitlin and Hodgson (2016) took the broadest view of responsibility to family caregivers, stating that not reaching out to family caregivers is unethical. Barnard and Yaffe (2014) thought it appropriate to argue against patient choices, when the cost to the family caregiver's health is too great. Mitnick et al. (2010) take a middle road. They recommend respect for patient's dignity, rights and values should guide patient/physician/caregiver interactions, but physicians should validate the family caregiver's role, remain alert for signs of distress, refer appropriately and develop separate care plans (patient, caregiver). The physician's plans should focus on maximising patient and caregiver quality of life.

Identifying caregivers, monitoring caregiver mental and physical health, providing information and emotional support, and referring caregivers to education and/or services were suggested roles for primary care practices, but physicians had divergent perspectives on their preferred role involvement with caregivers. To illustrate, a recent American survey found physician/caregiver interactions focused on medical tasks (Skufca, 2019), Dutch physicians over 50 felt they should take on a steering role (Doekhie et al., 2018) and general practitioners in the United Kingdom thought they had roles in providing emotional support and service referral, but expected to delegate support and referrals to an appropriate staff member (Jones et al., 2012).

There seem to be few services specifically for caregivers within primary care practices. In the survey of general practitioners in the United Kingdom (n = 79), 73% did not respond to the question ‘Does your practice offer any services specifically for carers?’ (Greenwood et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2012). Nine per cent offered caregivers’ information packs or pamphlets and 9% identified the caregiver in their records.

Referrals to other services were regarded an important part of their role, but physicians were frustrated by the hodge-podge nature of the health system whenever care for patients and caregivers extended beyond their clinical role (Bedard et al., 2014; Burridge et al., 2017; Burridge et al., 2011; Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Doekhie et al., 2018; Foley et al., 2017; Gill et al., 2014; Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010; Greenwood et al., 2010; Hum et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2012; Kiceniuk et al., ND; Krug et al., 2018; Leu et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2010; Skufca, 2019; Sunne & Huntington, 2017; Thyrian & Hoffmann, 2012; Wang et al., 2018). Lack of knowledge of available resources and services was commonly reported. To illustrate, Hum et al. (2014) provided this quote: ‘There should be some kind of book that I can use; and it should be published every year…’ (p. 98). Canadian physicians were frustrated by long wait times or referrals to specialists and by publicly funded services such as homecare that did not meet caregivers needs and expectations (Hum et al., 2014; Kiceniuk et al., ND). Physicians suggested that non-physician members of their team or community organisations could be more effective at providing education and helping caregivers to find timely appropriate services (Burridge et al., 2017; Burridge et al., 2011; Carduff et al., 2014, Doctors of BC, 2016b; Foley et al., 2017; Greenwood et al., 2011; Greenwood et al., 2010; Hum et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2012; Leu et al., 2018; Krug et al., 2018 Moore et al., 2018; Princess Royal Trust, 2011; Sunne & Huntington, 2017; Thyrian & Hoffman, 2012; Wang et al., 2018).

3.2 Collaborative, integrated care models are recommended

Collaborative, integrated care models were recommended as the route to reorganising primary care to meet caregivers’ needs (Bedard et al., 2014; Burridge et al., 2011, 2017; Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Doekhie et al., 2018; Foley et al., 2017; Gill et al., 2014; Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010; Greenwood et al., 2010; Hum et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2012; Kiceniuk et al., ND; Krug et al., 2018; Leu et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2010; Skufca, 2019; Sunne & Huntington, 2017; Thyrian & Hoffmann, 2012; Wang et al., 2018). Two medical associations (Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Princess Royal Trust, 2011) have developed toolkits to help physicians organise their practices to support caregivers.

These toolkits (Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b) assume that primary care physicians/primary care practices can provide ongoing care and support to caregivers. Within primary practices, they advise that a caregiver's champion, advanced practice nurse or navigator should be designated to identify caregivers, coordinate care and assist caregivers to navigate health and community systems. It also was noted that links to specialists, homecare and community organisations could be strengthened and that caregiver or disease-specific community organisations could collaborate to provide education, support and increase social participation. However, in the policy paper that accompanies the Circle of Care: Supporting Family Caregivers in BC toolkit Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b), doctors recommended that governments and other partners need to work together to develop and implement a collaborative healthcare approach ‘that recognises, includes, and supports caregivers as partners in care’ (p. 4).

3.3 Actualising support for caregivers in primary care remains elusive

The ways and means to actualising consistent support for caregivers within primary care practices remains elusive (Bedard et al., 2014; Burridge et al., 2011, 2017; Carduff et al., 2014; Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Doekhie et al., 2018; Foley et al., 2017; Gill et al., 2014; Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010; Greenwood et al., 2011; Hum et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2012; Kiceniuk et al., ND; Krug et al., 2018; Leu et al., 2018; O'Connor, 2011; Skufca, 2019; Sunne & Huntington, 2017; Thyrian & Hoffmann, 2012; Wang et al., 2018). As Krug et al. (2018) observed that expecting primary care physicians to reorganise busy practices to support caregivers is insufficient and that existing structures need to be recognised and reorganised. Robinson et al. (2010) submit that caring for caregivers in primary care requires the same systematic approach as the management of other long-term chronic conditions. However, they also note that there are facilitators and barriers at practice, system and policy levels that must be addressed if we are to realise primary care practices’ potential to care for, and support caregivers.

3.4 Facilitators and barriers to caregiver-centred support in primary care

We expanded on our thematic analysis to provide insight on the facilitators and barriers that need to be addressed if we are to enable primary care physicians and practices to provide caregiver-centred care.

3.4.1 Practice level facilitators and barriers

Having the caregiver as a registered patient in the practice and establishing practice protocols to support caregivers facilitated care for caregivers. Ethically and practically, physicians were more comfortable supporting caregivers if the caregiver was also a patient in their practice. For example, Canadian family physicians strongly agreed or agreed that assessing caregiver needs and distress, providing support or recommending/coordinating social services if the caregiver was their patient was reasonable, but were neutral or disagreed when the caregiver was not a patient (Bedard et al., 2014). An established caregiver/ physician relationship also enabled recognition of, and discussion about, caregiver concerns.

Practice protocols such as a designated person to coordinate care for caregivers, checklists and patient-centred care policies increased consistency. Caregivers benefit from individualised, innovative and flexible approach to support and assessment that takes account of both social and medical needs (Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Princess Royal Trust, 2011). Professionals taking a person-centred approach regarded informal caregivers as key partners in care of the care recipient as well as persons with needs of their own (Doekhie et al., 2018).

Caregiver characteristics, insufficient education about caregivers, and lack of time and reimbursement were practice level barriers to supporting caregivers. Caregivers tend to not self-identify, nor ask for help which makes it difficult for physicians to approach them as caregivers (Burridge et al., 2017; Carduff et al., 2014). American physicians (n = 241) rated patients having multiple caregivers (54%) and not being aware of who the caregiver is (44%) as the top barriers to supporting caregivers (Skufca, 2019). Just as doctors focus on the patient, caregivers also concentrate on the care-recipient's needs and tend to overlook their own well-being. If caregivers do not raise their concerns, norms of the patient–doctor interactions may prevent physicians from asking about their health (Burridge et al., 2011). Practically, because of the care-recipient's complex needs, caregivers may not be able to leave the home to attend appointments or take advantage of physician's referrals to services or caregiver education.

Physicians may need more education about caregiver roles, stressors and contributions, but there are conflicting results. In a UK study of 95 GPs, 9 in 10 general practitioners [GPs] (89%) felt they had insufficient training and approximately half (47%) lacked confidence that they were meeting carers’ needs (Greenwood et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2012). In a preliminary report of the Primary Care for Caregivers study in Canada, Kiceniuk et al. (ND) quoted one physician's concern about education: I think whenever we talked about dementia or other caregiver burden type diseases, it would be sort of like a bullet at the end of a slide—saying don't forget to check for caregiver burden or realise that there is caregiver burden… So it was mentioned a few times but never really taught comprehensively. In contrast, a survey of American primary care providers (Physicians n = 267), 82% were extremely or very interested in working with caregivers and 73% were extremely or very confident working with caregivers (Skufca, 2019).

The reimbursement for the time spent with caregivers may be inadequate, particularly if the caregiver is not the doctor's patient (Bedard et al., 2014; Burridge et al., 2011, 2017; Carduff et al., 2014; Doctors of BC 2016a,2016b; Doekhie et al., 2018; Foley et al., 2017; Gill et al., 2014; Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010; Greenwood et al., 2011; Hum et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2012; Kiceniuk et al., ND; Krug et al., 2018; Leu et al., 2018; O'Connor, 2011; Skufca, 2019; Sunne & Huntington, 2017; Thyrian & Hoffmann, 2012; Wang et al., 2018). To illustrate, in preliminary results from an ongoing Primary Care for Caregivers Study Kiceniuk et al. (ND) reported that in Nova Scotia physicians cannot bill for time spent talking to caregiver unless the caregiver is a patient and had booked an appointment separately from the patient. Similarly, in Ontario, Bedard et al. (2014) stated that ‘most physicians reported they do not have enough time to interact with caregivers and some that they are not adequately reimbursed for supporting caregivers’ (p. 223).

In summary, results from this literature indicate caregiving issues can be complex, emotionally draining and time-consuming for physicians. It is unlikely that primary care practices can provide all the support caregivers need, so knowing where to refer caregivers for help is necessary. In the UK in 2010, about one of five survey respondents provided information about services or referrals to organisations and agencies (Greenwood et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2012). Developing and maintaining lists of services and supports required by diverse caregivers is time-consuming and onerous for individual practices.

3.4.2 Health and community systems level facilitators and barriers

Electronic health records are a promising system level innovation that should facilitate communication between primary care, specialists and hospitals (Gill et al., 2014). Clinicians should be able to make referrals and communicate with colleagues efficiently as electronic health records are introduced. We identified three systems level barriers in the papers included in this review: (a) the health system continues to focus on patient's care, (b) health and community systems are complex and disjointed and (c) services needed to support caregivers are unavailable or difficult to find. With respect to the first theme, despite system reforms, the health system continues to focus on patient care, support for caregivers receives less attention. In addition, ethics guidelines for physicians on working with caregivers provide conflicting advice (Barnard & Yaffe, 2014; Gitlin & Hodgson, 2016; Mitnick et al., 2010).

With respect to health and community systems, an identified major barrier is that these systems continue to operate in silos. While collaborative, integrated care that includes referrals to community organisations (e.g. Alzheimer's, Parkinson's Caregivers) is recommended, the ways for health professionals to refer to, and receive information from, the community organisations are not well established. Even in urban areas with well-developed health and social care systems, the services and supports caregivers may need are not available. Caregiver education, as well as a rehabilitation or a palliative approach to care are often offered in particular locations only which means that these supports may not be accessible to caregivers who do not reside near the service, lack access to transportation or cannot find or afford respite for the client while they are away,

3.4.3 Policy facilitators and barriers

Clear policies directing physicians to assess and support caregivers with funding attached could improve the ability of the primary care physicians to reorganise their practices to support time and energy-consuming caregivers. The UK Quality and Outcomes Framework rewards general practitioners financially for specified caregiver care (Greenwood et al., 2010; Greenwood et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2012; Princess Royal Trust, 2011). However, Canada has no federal Canadian legislation recognising caregivers. There have been some initiatives at the provincial level. For example, in Manitoba, Canada, the 'Caregiver Recognition Act' (2011) includes the principle that ‘Support for caregivers should be timely, responsive, appropriate and accessible’ (p. x), but there is no guidance as to who should provide support nor is there enforcement: ‘In addition, this Act does not create rights or duties that are legally enforceable in court or other proceedings’.

Professional ethics policies are also a barrier. Currently, ethics policies do not provide clear guidelines for caregiver support (Barnard & Yaffe, 2014; Gitlin & Hodgson, 2016; Mitnick et al., 2010). Doctors of British Columbia (2016a,2016b) have produced a policy document, Circle of Care: Supporting Family Caregivers in BC and a toolkit for doctors to organise their practices to support family caregivers. They recommend that the BC government develops caregiver strategy to formally recognise caregivers in service planning and health delivery (see Table 3).

| Facilitators | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|

| Practice level |

Family caregiver is also patient in the practice. Physicians were more comfortable supporting caregivers registered as patients in their practice. Established relationship with family caregiver. Relationship enabled recognition and discussion about caregiver concern. Establishing practice protocols to support caregivers. Included protocols for identifying family caregivers, designated person to coordinate caregiver's care and patient-centred policies |

Caregiver characteristics. Family caregivers do not identify as caregivers nor ask for help. They tend to focus on the patient's health while overlooking their own health. Practically, those caring for high-care needs recipients may not be able to leave home to attend appointments. Lack of time and reimbursement. Care for caregivers is often complex and time-consuming. There may not be billing codes for time spent with caregivers. |

| Health and community systems level | Electronic health records. Should facilitate communication between primary care, specialists and hospitals. |

Focus on the patient. Ethics guidelines and mandates focus on the patient's needs. Disjointed health and community systems. Collaborative, integrated care that includes appropriate referrals to community services is recommended but cross-referral systems are not established. Services and supports unavailable/difficult to access. Caregivers may lack access to transportation and respite for care recipient. |

| Policy level | Clear policies with funding attached that direct physicians to assess and support caregivers. UK has policy and billing code for GPs to identify caregivers in their practices. | Lack of policy and ethics guidance. Care is inconsistent without clear policy and ethical mandates. |

4 DISCUSSION

Primary care physicians almost unanimously agree that caregivers would benefit from support from primary care teams. Collaborative, integrated care models that include physicians, a designated caregiver coordinator or case manager, and community support organisations are regarded as the most feasible models. Despite this goodwill, there are many barriers to primary care physician's ability to consistently identify and support caregivers (see Tables 2 and 3). Currently, the physician's role in caregiver-centred care is not well defined and varies widely. Caregivers do not tend to self-identify or ask for support. There is an expectation that family physicians will refer patients and families to the appropriate services and supports and information from physicians is highly valued, but may not be offered in a timely manner (Turnpenny & Beadle-Brown, 2015). Family caregivers now spend 15%–50% of their time negotiating health and social care systems, and then managing the care and services from siloed health and social care services (Taylor & Quesnel-Vallée, 2017).

Typically, health and community systems operate in silos, which makes it onerous for physicians to refer across systems and assist caregivers to navigate the disparate services. Caregiving is not regarded as a medical issue, yet meeting caregivers needs tend to be complex and time-consuming. Physicians thought they lacked the time to address the issues caregivers face and feel inadequately remunerated for the caregiver care they currently provide (see Table 3). Schulz et al. (2018) and Schulz and Czaja (2018) refers to such barriers as a ‘confluence of structural and process barriers’ (p. 358). Seven authors cited knowing where to refer caregivers for services as a barrier (see Table 2). Now, some nations and local communities have centralised referral services, so primary care practices do not find it necessary to have to keep up-to-date resource lists. In the United States, for example, the family Caregiver Alliance and area Agencies on Ageing are funded to keep updated resource lists. In the United Kingdom, general practices can register with Carers UK access to up-to-date resources. However, American physicians did perceive in-office materials were the most impactful caregiver resources (Skufca, 2019).

Optimising support and care for family caregivers will require systematic identification, assessment and support throughout the care trajectory, and in the settings of both health and community systems (Schulz et al., 2018; Schulz & Czaja, 2018). As many family caregivers do not consider themselves caregivers, simply asking ‘Are you “looking after” or “helping” a friend or relative who is ill or disabled’ is recommended (Princess Royal Trust, 2011). It is insufficient to just expect primary care physicians to support family caregivers. Changes are needed at the practice, health and community systems, and policy levels. To date, pressure for caregivers’ supports has come mainly from the research community and not-for-profit organisations such as the American Association of Retired Persons or Carers UK (Byrne, 2016; Levine, 2011; Schulz et al., 2018). Broader support is likely needed.

Inasmuch as physicians report feeling unprepared to assess and support family caregivers, system and policy level changes are needed. Medical school curricula and continuing medical education should incorporate training to increase proficiencies to identify, assess and support family caregivers. Macro-level policy changes that mandate caregiver support in standards of care, accreditation and remuneration for time caring for caregivers are also required.

Multi-level, interdisciplinary collaborative relationships and the sharing of goals and ideas are required to effect complex system change (Bevan & Fairman, 2017; Peckham, Morton-Chang, Williams, & Miller, 2018). Policy changes, such as the reimbursements for identifying caregivers (e.g. US Medicare code 99,438; Benton & Meyer, 2019), UK GP carers registry; Greenwood et al., 2010) and inclusion of specific goals in the UK’s Long-Term Plan for the National Health Service (Carers UK, 2019) are examples of tangible changes to increase support for family caregivers in primary care.

In addition to primary care practices being the first line of support, information and support from professionals are highly valued (Turnpenny & Beadle-Brown, 2015). Most people trust their family physician's perspectives (Rolfe, Cash-Gibson, Car, Sheikh, & McKinstry, 2014). Trust in healthcare providers is associated with increased satisfaction, adherence to treatment and continuity of care (Rolfe et al., 2014), all of which should improve caregivers’ health.

4.1 Limitations

This review is limited by the paucity of information on primary care support for caregivers from the perspective of primary care physicians. Many of the reports in this review included perspectives of only a few physicians. Better appreciation of primary care physicians and primary team members is required to provide actual data about their attitudes, beliefs, level of knowledge, perceived barriers and perceptions of the support that caregivers require (Bedard et al., 2014; Greenwood et al., 2010). The findings are also limited by lack of research in how primary care teams have effected change and therefore do not consider physicians perspectives of how they might enable practice and policy innovations to support family caregivers.

5 CONCLUSION

Undoubtedly, there is increased awareness that caregivers need support. Primary healthcare teams are well positioned to connect caregivers to both primary care practices and their communities, but the policy and funding required to drive change has been limited. Physicians’ perspectives about caregiver interactions are needed to inform health and community service planning. Future work to address these limitations is needed to support caregivers throughout their care trajectory.