“Caregiving is a full-time job” impacting stroke caregivers' health and well-being: A qualitative meta-synthesis

Abstract

Family caregivers contribute to the sustainability of healthcare systems. Stroke is a leading cause of adult disability and many people with stroke rely on caregiver support to return home and remain in the community. Research has demonstrated the importance of caregivers, but suggests that caregiving can have adverse consequences. Despite the body of qualitative stroke literature, there is little clarity about how to incorporate these findings into clinical practice. This review aimed to characterise stroke caregivers' experiences and the impact of these experiences on their health and well-being. We conducted a qualitative meta-synthesis. Four electronic databases were searched to identify original qualitative research examining stroke caregivers' experiences. In total, 4,481 citations were found, with 39 studies remaining after removing duplicates and applying inclusion and exclusions criteria. Articles were appraised for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), coded using NVivo software, and analysed through thematic synthesis. One overarching theme, ‘caregiving is a full-time job’ was identified, encompassing four sub-themes: (a) restructured life, (b) altered relationships, (c) physical challenges, and (d) psychosocial challenges. Community and institution-based clinicians should be aware of the physical and psychosocial consequences of caregiving and provide appropriate supports, such as education and respite, to optimise caregiver health and well-being. Future research may build upon this study to identify caregivers in most need of support and the types of support needed across a broad range of health conditions.

What is known about this topic:

- Stroke is a leading cause of adult disability with the majority returning to live in the community.

- The majority of people with stroke living in the community receive support from family caregivers

- Caregivers to people with stroke often experience poor mental and physical health

What this paper adds:

- This review highlights the life altering nature of caregiving to stroke survivors and the various ways the caregiving role affects caregiver health and well-being

1 INTRODUCTION

Approximately one-third of Canadians aged 45 or older provide informal care for an individual with health concerns (Turner & Findlay, 2012). These family caregivers (e.g., a relative, partner, friend or neighbour), provide assistance without financial compensation (Bakas et al., 2014) and make a valuable contribution to the sustainability of the health system by delaying or preventing institutional care (Chari, Engberg, Ray, & Mehrotra, 2015; Chen et al., 2019; Forbes & Neufeld, 2008; Wimo et al., 2013).

Stroke is the leading cause of neurological disability in adults worldwide (Katan & Luft, 2018). Many, if not all, people with stroke will require assistance throughout their recovery. Family caregivers make an important contribution supporting people with stroke living in the community (Greenwood, Mackenzie, Cloud, & Wilson, 2009; Heugten, Visser-Meily, & Post, Lindman, 2006). Due to the sudden onset of stroke, caregivers often take on this new role with little or no preparation (Smith, Lawrence, Kerr, Langhorne, & Lees, 2004) leading to a sense of feeling ill-prepared or questioning their own competence (McKevitt, Redfern, Mold, & Wolfe, 2004). As a result, caregivers may experience a decline in their physical and mental health status, social life and general well-being (Bakas et al., 2014; Heugten et al., 2006; Low, Payne, & Roderick, 1999).

Existing reviews of predominantly quantitative literature suggests that caregivers are at risk for poor mental health outcomes (Brandon, 2013; Northcott, Moss, Harrison, & Hilari, 2016). Quantitative studies have highlighted key factors associated with depressive symptoms in caregivers. These factors relate primarily to the caregiver and caregiving situation, such as the difficult and time-consuming nature of care tasks (Bakas, Austin, Jessup, Williams, & Oberst, 2004; Bakas & Burgener, 2002) and not to patient functional status or patient or caregiver sociodemographic characteristics (Grant, Bartolucci, Elliot, & Giger, 2000).

Qualitative studies provide a comprehensive picture of caregivers' unique experiences that may not be captured by quantitative measures (Greenwood et al., 2009). Moreover, qualitative research may provide a detailed description of the impact of caregiving on caregiver health and well-being and factors that influence caregiver health status that are essential in the development of interventions and services. Reviews and syntheses of qualitative literature, in turn, are important for evidence-based practice (Salter, Hellings, Foley, & Teasell, 2008).

Previous reviews of qualitative literature have explored the diversity of challenges experienced by patients and caregivers and have supported the use of qualitative methodologies (e.g., Greenwood et al., 2009: Carstensen, McKevitt et al., 2004; Murray, Ashworth, Forster, & Young, 2003). However, earlier reviews focused on patient outcomes, with caregiver outcomes as a secondary aim (Lou, Jørgensen, & Nielsen, 2017). Murray et al. (2003), for example, combined the challenges experienced by patients and their caregivers, but acknowledged that appropriate interventions would require separate assessments of patients' and caregivers' needs. This study suggests the need for longer-term stroke support for patients' and caregivers' and supports the need for future research to identify broader treatment strategies for supporting patients' and caregivers' (Murray et al., 2003).

McKevitt et al. (2004) suggested, future reviews should employ new strategies to pool qualitative research findings. Qualitative systematic reviews and meta-syntheses of stroke patients' and informal carers' experiences with life after stroke have been conducted, however, they focus primarily on experiences related to health service use (e.g., rehabilitation) (e.g., Greenwood et al., 2009; Lou et al., 2017) or familial relationships (e.g.,Greenwood & Mackenzie, 2010; Jones & Morris, 2013; Quinn, Murray, & Malone, 2014). Greenwood et al. (2009) focused solely on the challenges and satisfactions associated with caregiving. They summarised the positive and negative impact of caring, and described the satisfactions and strategies for coping. A specific focus on health and well-being implications were not included in this review.

Although, the qualitative research exploring caregiver experiences is abundant, there is little clarity about how to translate qualitative findings into clinical practice (Stergiou-Kita et al., 2014). As rigorous methods of synthesising qualitative literature are emerging, more qualitative meta-syntheses are being conducted (e.g., Quinn et al., 2014; Salter et al., 2008). Due to the increase in validity through systematic sampling, audit trails and triangulation (Finfgeld-Connett, 2010), a meta-synthesis approach may make the qualitative literature a more influential body of evidence. By systematically synthesising large bodies of qualitative research, meta-synthesis can make the body of qualitative knowledge more accessible, develop recommendations for evidence-based practice and identify areas for future research (Gewurtz, Stergiou-Kita, Shaw, Kirsh, & Rappolt, 2008; Thomas & Harden, 2008; Walsh & Downe, 2005). Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative meta-synthesis was to review the qualitative literature to characterise the experiences of caregivers and the impact of these experiences on caregiver health and well-being.

2 METHODS

Our methods have been reported in accordance with some of the ENTREQ guidelines (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, 2012).

2.1 Research design

This review adopted a qualitative meta-synthesis approach. (Stergiou-Kita et al., 2014; Thomas & Harden, 2008; Walsh & Downe, 2005; Zimmer, 2006). Qualitative meta-syntheses include the following: (a) identifying a relevant research question, (b) setting inclusion and exclusion criteria, (c) identifying and retrieving studies, (d) assessing quality of studies, and (e) synthesising findings across studies (Gewurtz et al., 2008).

2.2 Participants

Studies whose participants were caregivers of people with stroke and articles published in English-language peer-reviewed journals were included. Studies were excluded if: (a) no qualitative data were presented, (b) caregiver data were not separated from stroke survivor data, and (c) caregiver health and well-being were not examined. For the purposes of this review, the definition of health, adapted from the World Health Organization, encompassed an individual's physical, mental and social well-being (Constitution of the World Health Organization, 2006).

2.3 Search strategy and retrieval of studies

The literature search was carried out by five reviewers and an Information Specialist. Research papers were identified through a search of four electronic databases, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CIHNAL), Medline, PsychINFO and Cochrane Library Database, covering all publications up to November 30, 2018. The researchers mapped terms to existing subject headings in each database and used keyword searching with and without truncation. Search terms included: ‘caregiver’, ‘carer’, ‘spouse’, ‘cerebrovascular accident’ and ‘stroke’, which have been used by previous reviews (Greenwood et al., 2009; Salter et al., 2008).

Reference lists from identified papers and review articles were hand-searched to supplement the electronic search. Once the initial articles were identified, the titles and abstracts of a random selection of 25 articles were reviewed by three authors (KMK, FKTL and JRS) to determine interrater reliability (K = 0.93). The three authors reviewed the remaining titles and abstracts using the established criteria and uncertainty was discussed until consensus was achieved. All three authors have experience conducting qualitative research and have completed graduate-level coursework on qualitative methods.

2.4 Quality rating

The included qualitative articles were assessed for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). The CASP consists of 10 questions relating to the appropriateness of the study methodology, sampling strategy, clarity of data collection, analysis and procedures, consideration of bias and ethical issues, as well as accessibility and significance of the findings. The results of the CASP assessment can be found in Table 1 and is summarised and described below.

| Author | CASP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of research? | 2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | 3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of research? | 5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? |

8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? |

9. Is there a clear statement of findings? |

10. How valuable is research? |

|

| Arabit,L.D. | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low - pilot study |

| Backstrom,B.; Sundin,K. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Bakas T; Austin JK; Okonkwo KF; Lewis RR; Chadwick L | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Barbic SP; Mayo NE; White CL; Bartlett SJ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Bastawrous M; Gignac MA; Kapral MK; Cameron JI | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Bastawrous M; Gignac MA; Kapral MK; Cameron JI | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Bocchi SC; Angelo M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Bulley, Cathy; Shiels, Jane; Wilkie,Katie; Salisbury, Lisa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Buschenfeld, Karin; Morris,Reg; Lockwood, Sally | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Cao V; Chung C; Ferreira A; Nelken J; Brooks D; Cott C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Cecil, Rosanne; Thompson, Kate; Parahoo,Kader; McCaughan, Eilis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Chow,Celia; Tiwari,Agnes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Cobley CS; Fisher RJ; Chouliara N; Kerr M; Walker MF | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Coombs,U.E. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Danzl MM; Hunter EG; Campbell S; Sylvia V; Kuperstein J; Maddy K; Harrison A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| El Masry Y; Mullan B; Hackett M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| Gosman-Hedstrom G; Dahlin-Ivanoff S | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Green TL; King KM | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Greenwood N; Mackenzie A; Cloud G; Wilson N | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Gustafsson L; Bootle K | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Johnson,P.D. | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Kitzmuller, Gabriele; Asplund,Kenneth; Haggstrom, Terttu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Lee, Regina L. T; Mok,Esther S.B. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Low JT; Roderick P; Payne S | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Moore LW; Maiocco G; Schmidt SM; Guo L; Estes J | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| O'Connell B; Baker L | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Pierce,L.L. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Pierce LL; Thompson TL; Govoni AL; Steiner V | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Rodrigues et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Saban & Hogan | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Silva-Smith | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Smith et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Subgranon & Lund | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Thomas & Greenop | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Medium |

| Thompson et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| Van Dongen, Josephsson Ekstam | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Winkler et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

2.5 Data extraction and synthesis of findings

This study drew upon synthesis approaches described by previous qualitative meta-syntheses (Levack, Kayes, & Fadyl, 2010; Mudge, Kayes, & McPherson, 2015; Walsh & Downe, 2005). The procedure began by extracting general characteristics from each study. Data from the results section of the articles were imported into QSR NVivo 11, a computer software that assists researchers with the management and analysis of qualitative data (Levack et al., 2010; QSR International, 2005). Two reviewers (FKTL and JRS) coded a subset of articles to initiate codebook development. Through an iterative process, the codes were discussed and finalised to ensure consistency in coding. Thereafter, articles were coded line by line. Reciprocal translation methods were used to ensure that codes were applied consistently across articles by analysing subsequent studies in comparison with previously coded articles. Coded data were then grouped to develop descriptive themes with all authors. In order to go beyond the descriptive themes, all authors described the experiences of caregivers, first independently and then as a group until new themes encompassing the initial descriptive themes, the inferred caregiving situations and its implications on health and well-being were developed.

3 RESULTS

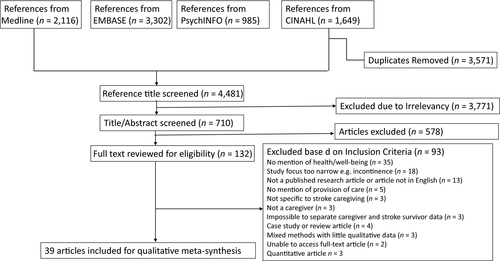

In total, 4,481 citations were identified. After removing duplicates, the most frequent reasons for exclusion were not explicitly addressing caregiver health and well-being (see Figure 1). No additional studies were identified from the reference lists of included articles or existing reviews. See Table 2 for the general characteristics of qualitative studies examining experiences of stroke caregivers.

| Study | n | Participants | Setting and format of data collection | Data analysis style reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arabit, 2008 (USA) |

5 |

All female Age 57–85 All wives All Latino decent |

Approx. 1-hr interviews using an interview guide, conducted in an inpatient rehab facility. Three telephone and two in- person interviews. | Grounded theory using constant comparative method |

|

Bäckström & Sundin, 2009 (Sweden) |

9 |

Seven female, two male Age 40–64 Six partners or spouse, one partner, two mothers, eight relatives Ethnicity not reported |

40–75-min interviews using open-ended questions, conducted in the author's office (2), conference room (1), participants work (4) or participants home (2). | Thematic analysis |

|

Bakas et al., 2002 (USA) |

14 |

All female Age not specified seven daughters, four wives, three other relatives eight African American with the remainder white |

Telephone interviews were conducted with all but one of the caregivers, who was interviewed in person in the clinic setting, using five open-ended questions. | Thematic analysis |

|

Barbic 2014 None listed |

30 |

75% female Mean age 54 63% spouses, 30% adult children, 7% other relatives. Ethnicity not specified. Mean 21 months of caregiving experience. |

30–45-min semi-structured telephone interview in caregiver's language of choice. | Secondary thematic qualitative analysis |

|

Bastawrous, 2014 (Canada) |

23 |

All female daughters Age 38–54 Ethnicity not specified Provided care for 0.5–36 months. |

Approx. 46-min interviews conducted over telephone (20/23) or in person (3/23) using open-ended questions. | Thematic content analysis |

|

Bastawrous, 2015 (Canada) |

23 |

All female Age 38–54 All daughters Mean 6 months of caregiving experience |

In-depth telephone (21) or in-person (2) interviews guided by a set of open-ended questions. | Thematic analysis |

|

Bocchi, 2008 (Brazil) |

10 |

Nine female, one male Age 36–69 Six spouses, two daughters, one mother-in-law, one stepmother Ethnicity not specified Providing care for 3 months to 5 years |

Interviews were conducted in the caregivers' own homes. | Grounded theory using Symbolic Interactionism according to Charon |

|

Bulley, 2010 (UK) |

9 |

Seven females, two males Age range provided 40–44 to 70–74 All spouses All white British |

Semi-structured interviews conducted in participants home. Three joint interviews and six individual caregiver interviews. | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

|

Buschenfeld, 2009 (UK) |

7 |

Three females, four males Age 49–62 All partners All white British or European origin |

Approx. 90-min semi-structured interviews conducted in the participant's home (6) or at the interviewer's place of work (1). | Interpretive phenomenological analysis outlined by Smith et al. |

|

Cao, 2010 (Canada) |

10 |

All female spouses Age 45–73 Mean 2–5 years providing care |

Approx. 1-hr semi-structured interviews consisting of seven open-ended questions, conducted either face-face or via telephone. | Thematic analysis |

|

Cecil, 2013 (UK) |

30 |

23 females, seven males Age 36–84 19 spouses, seven children, three sisters, one other relative |

Semi-structured interviews conducted in carers' homes approx. 6 weeks following hospital discharge. Data collection ran from late 2008 to early 2010. | Thematic analysis |

|

Chow, 2014 (Hong Kong) |

29 |

21 female, eight male Age 42–87 12 spouses, 12 children |

Six focus group interviews, consisting of 3–6 caregivers, conducted in a community centre. All interviews used a semi-structured interview guide and lasted 60–90 min. | Thematic content analysis |

|

Cobley, 2013 (UK) |

15 |

13 female, two male Age 56–83 All spouses |

30–45-min semi-structured interviews guided by a structured interview framework. All interviews conducted in the patients' usual place of residence. | Thematic analysis |

|

Coombs, 2007 (Canada) |

8 |

Five females, three males Age 57–81 All spouses 1.5–5 years providing care |

60–120-min semi-structured interviews conducted in participants' home (7) or alternate location (1). Each participant engaged in two separate interviews. |

Thematic analysis |

|

Danzl, 2013 (USA) |

12 |

Seven females, five males Age 38–75 Six spouses, six children All white |

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews using an interview guide. Interviews location determined by participants (homes (9), regional hospital meeting centres (30, and residential nursing facilities (2)). |

Content analysis |

|

El Masry, 2013 (Australia) |

20 |

16 females, four males Age range provided 31–40 to 81–90 15 spouses, two children, three siblings Nine Anglo-Australian, two European (English-speaking country), seven European (non-English speaking country), one South American, one South East Asian <12 months to 2 + years providing care |

Approx. 60-min semi-structured interviews. Majority of stroke survivor and caregiver interviews (except for three caregiver interviews) were completed separately. Each caregiver and stroke survivor was interviewed once. | Interpretive phenomenological analysis |

|

Ghazzawi, 2016 (Canada) |

14 | Stroke survivor must have been living at home for 4 − 12 weeks following post-discharge from a rehabilitation facility. | Interviews were conducted in person, or by telephone using a semi-structured interview guide. Stroke survivors were not present during the interviews. Interviews were 30 − 45 min in length. | Content Analysis |

|

ContenGosman-Hedstrom, 2012 (Sweden) |

16 |

All female spouses Age 66–83 2–15 years providing care |

Four focus groups, comprising three to five members, met once for no more than 2 hr. | Based on the qualitative method as described by Krueger |

|

Green, 2009 (Canada) |

26 |

26 married couples Age 33–75 96% wife-caregivers were Caucasian, 4% listed as Other |

Approx. 45–60-min semi-structured telephone interviews conducted at 1, 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months following the index hospital discharge. Caregivers interviewed individually when possible. | Thematic content analysis |

|

Greenwood, 2009 (UK) |

31 |

22 female, nine male Age 30–66+ 16 spouses, 13 children, two siblings 18 White British, four Other White, four Asian, two Black, three Other |

30–90-min in-depth interview just prior to discharge, 1 month, and 3 months post-discharge. 23 carers interviewed three times, four interviewed twice and four interviewed once. In three cases, two carers were interviewed for one survivor. First interviews were in side rooms in hospital or carers' homes, second and third interviews were conducted in carers' homes. | Thematic analysis |

|

Gustafsson, 2013 (Australia) |

5 |

Three female, two male Three spouses, one child, one friend |

Semi-structured interviews conducted in participants' homes 1 month after discharge. Clients and carers interviewed separately. | Inductive thematic analysis |

|

Johnson, 1998 (USA) |

10 |

Five female, five male Age 38–82 Six spouses, three children, one daughter-in-law All Caucasian |

Single, in-depth semi-structured interviews guided by seven open-ended probe questions were conducted in the caregivers' homes. | Thematic analysis |

|

Kitzmuller, 2012 (Norway) |

17 |

13 women, four men Age 32–65 All spouses Ethnicity not specified |

60–210-min interviews, in Norwegian language, guided by an open approach design.. 11 individual spouse interviews and six joint interviews. After the couple interviews, three spouses were interviewed separately. Interviews conducted in participants' homes (35) or in a hotel room (2). |

Hermeneutic phenomenological analysis |

|

Lee & Mok, 2011 (China) |

15 |

10 females, five males Age 28–87 62 wives, five husbands, three daughters All Chinese |

1–2-hr in-depth interviews. One participant was interviewed four times, another three times, and the remaining interviewed once or twice. | Grounded theory using constant comparative method |

|

Low, 2004 (UK) |

40 | Mean age 68.7 Mainly spouses and partners | Semi-structured interviews at baseline and 6 months. | Content analysis carried out on all transcripts. Further in-depth thematic analysis conducted on a sample of 15 transcripts. |

|

Moore, 2002 (USA) |

8 |

Five female, three male Age 30–80 Three husbands, two wives, two children, one sister Ethnicity not reported |

Single telephone interviews with a semi-structured questionnaire. | Thematic analysis |

|

O'Connell, 2004 (Australia) |

37 |

23 females, 14 males Age 23–86 21 spouses and partners, 13 children, three close relatives Ethnicity not reported |

Approx. 20–30-min semi-structured in-person or telephone interviews. | Thematic analysis |

|

Pesantes, 2017 (Peru) |

12 |

Eight female, four males |

Semi-structured interviews (2–5 times); short questionnaire designed to collect basic socio-demo graphic information of the caregiver and the stroke survivor. |

Thematic analysis |

|

Pierce, 2001 (USA) |

24 |

20 female, four male Age 58–81 Two husbands, three wives, 12 daughters, two sons, one granddaughter, one daughter-in-law, two sisters, one friend All African American 6 months−11 years providing care |

Three semi-structured interviews in home setting. Observation-participation occurred to a limited extent during the interviews with all informants | Thematic analysis |

|

Pierce, 2012 (USA) |

73 |

55 female, 18 male Mean age 55 34 wives, 16 husbands, 13 daughters, one son, nine other relatives or friends 62 White, nine African American, one Hispanic, one American Indian |

Sample characteristic data obtained through telephone interview. Other data obtained through email and telephone interview. Caregivers followed for 1 year. | Thematic content analysis |

|

Rodrigues, 2013 (Brazil) |

10 |

All female. Age 34–82 Seven daughters, three other Ethnicity not reported |

Semi-structured interviews at caregivers' homes, observations, existing documentation and field notes. | Thematic analysis |

|

Saban, 2012 (USA) |

46 |

All female. Age 18–73 24 wives, 18 children, two significant others or mother of survivor Most white (38) |

Written, open-ended questionnaire | Thematic analysis |

|

Silva-Smith, 2007 (USA) |

12 |

Nine female, three male Age 38–78 Four wives, three husbands, two sisters, one mother, one daughter, one fiancée Six African American, six Caucasian |

Two audiotaped interviews pre- and post-discharge (4 weeks after the stroke survivor's hospital discharge). | Grounded theory using constant comparative method |

|

Smith, 2004 (UK) |

90 |

65 female, 25 male Age 19–84 64 married, one widowed Ethnicity not reported |

1–2-hr semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Subgranon, 2000 (Thailand) | 20 |

13 female, seven male Age 28–73 Six wives, four daughters, four sons, three daughter-in-laws, one son-in-law All Thai |

Single interviews in caregivers' homes, observations and researcher's memos. | Thematic analysis |

|

Thomas & Greenop, 2008 (South Africa) |

6 |

Four females, two males Four spouses, two adult children Time since stroke ranged 1.5–13 years |

Semi-structured interviews conducted at neurovascular clinic |

Content and thematic analysis |

|

Thompson, 2004 (USA) |

9 |

Four female, five male Age 51–72 Four husbands, one friend, one wife, one daughter and two daughter-in-laws. Eight Caucasian, one other. |

Bimonthly, semi-structured telephone interviews and online communication through ‘Ask the Nurse’ and ‘Caretalk’. | Framework of systemic organization by Friedemann (1995) |

|

Van Dongen, 2014 (Austria) |

3 |

All female Age 49–59 Two wives, one daughter 5–14 months providing care |

45–90-min semi-structured open-ended interviews, in German language, conducted twice with each participant. Interview location based on participants' preferences. | Interpretive phenomenological analysis |

|

Winkler, 2014 (UK) |

9 |

Nine females, one male Age not specified, estimated early 20s to 60s Six spouses, one mother, three daughters All white Caucasian |

Manual selection and validation of public blogs. Data from blogs still active were collected up to January 2013. For large blogs, with 90 or more posts, the first and last 30 relevant posts were collected and analysed. | "Framework" method as described by Ritchie and Spencer |

Thirty-nine studies remained after application of inclusion and exclusions criteria (Figure 1) with a total of 786 caregiver participants. The majority of the studies were from USA and UK with the remainder originating from countries around the world. Number of caregiver participants per study ranged from 3 to 90. Participants were identified from varying sources and most studies named ‘convenience’ or ‘purposive’ sampling. Although female caregivers were the dominant participant across studies, most studies (n = 31; 79.4%) also included males. Varying caregiver–survivor family relationships (e.g., spouse) were reported (see participants in Table 2), as well as a wide range of caregiver age, 18 to 87. Data were collected by in-person or telephone interviews, focus groups, email discussions and publicly available blogs. Only 13 (33%) reported when in the illness trajectory the data were collected.

The results of our Critical Appraisal Skills Programme assessment suggest that studies were generally of high quality with lower ratings assigned when limited detail regarding research context or methods was provided (see Table 1). All studies included a clear statement of the aims of the research and appropriately employed a qualitative research design. However, six studies used a recruitment strategy we deemed inappropriate. These six studies did not justify their participant inclusion criteria or provided limited information about the chosen recruitment strategy. All studies collected data in a way that addressed the research issue, primarily in the form of interviews. The majority of studies (n = 23) did not consider the relationship between the researcher and participants, yet most did consider ethical concerns in their research design (n = 31). Sufficient descriptions of data analysis were found in all studies. The novelty and overall value of the research to the field of stroke caregiving varied from high to low, with the majority of studies ranging from medium-high rankings (n = 24).

3.1 Caregiving is a full-time job

The analysis resulted in one overarching theme: ‘caregiving is a full-time job’. This overarching theme presented consistently across studies, as evidenced by the use of descriptors, such as “caring was relentless”, (Smith et al., 2004), “a full-time job” (Cao, 2010), being “on call”, (Saban & Hogan, 2012; Smith et al., 2004), “working a 24-hr day”, (Coombs, 2007), “24-hr duty” (Moore, Maiocco, Schmidt, Guo, & Estes, 2002) and having to be “accessible” to people with stroke (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009). As a result, the role of caregiving led to restructuring life, including altered relationships, and, ultimately, resulted in challenges to caregivers' physical and psychosocial health, described in the sub-themes below.

3.2 Restructuring life

Restructuring life was described through a variety of experiences reflecting caregivers' efforts to accommodate the care needs of the survivor, as well as manage multiple roles and responsibilities. These adjustments impacted various aspects of life, from everyday routines, participation in occupations, and personal time. Examples of these adjustments included changes to the physical household environment, (Silva-Smith, 2007), work schedules (Barbic, Mayo, White, & Bartlett, 2014; Silva-Smith, 2007) living arrangements, (Bastawrous, Gignac, Kapral, & Cameron, 22015; Coombs, 2007) and everyday routines (Silva-Smith, 2007).

There were many examples where the stroke event resulted in the caregiver taking on activities that had been the responsibility of the survivor (Buschenfeld & Morris &Lockwood, 22009; Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Cecil, Thompson, Parahoo, & McCaughan, 2013; Coombs, 2007; O'Connell & Baker, 2004; Silva-Smith, 2007). This typically happened as the caregiving role became more complex after the transition from acute care to the home (Chow & Tiwari, 2014). Caregivers commonly described “altered roles” (El Masry, Mullan, & Hackett, 2013; Smith et al., 2004) or “role reversals” (Bastawrous, Gignac, Kapral, & Cameron, 2014; Saban & Hogan, 2012; Thomas & Greenop, 2008) in which the caregiver had to carry out roles typically held by the person who experienced the stroke, including housework (Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2004; Winkler, Bedford, Northcott, & Hilari, 2014), driving (Bakas, Austin, Okonkwo, Lewis, & Chadwick, 2002; Cecil et al., 2013; Johnson, 1998), managing finances (Barbic et al., 2014; Cecil et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2004) or child-rearing (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Silva-Smith, 2007; Thompson et al., 2004; Winkler et al., 2014).

In addition, caregivers reported changes to their abilities to participate in meaningful activities. Many described having to reduce involvement in leisure activities, such as exercising, (Bastawrous et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2010; Silva-Smith, 2007), playing sports (Barbic et al., 2014; Bastawrous et al., 2015; Silva-Smith, 2007) and travelling (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Barbic et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2010; Johnson, 1998; Silva-Smith, 2007). Others discussed limited interactions with family and friends, (Buschenfeld et al., 2009; El Masry et al., 2013; Green & King, 2009; Saban & Hogan, 2012; Chow & Tiwari, 2014), often leading to feelings of social isolation (Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Kitzmüller, Häggström, Asplund, & Gilje, 2012; Chow & Tiwari, 2014). Changes in employment were frequently cited, as participants reported having to reduce work hours or give up work entirely to fulfil their caregiver role (Bastawrous et al., 2015; Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Cecil et al., 2013; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Thomas & Greenop, 2008). One participant reported, “I have no uninterrupted time for personal things, including showers/baths, TV program or a movie, a chance to read or paint or play the organ. No chance to leave the house for a walk or to bike” (Saban & Hogan, 2012, p. 6).

3.3 Altered relationships

Across numerous studies, caregivers suggested that caregiving resulted in altered relationships with the survivor (Bastawrous et al., 2015) and within the family (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Thomas & Greenop, 2008). Due to changes in typical marriage (Smith et al., 2004; Winkler et al., 2014) and parent–child roles (Bastawrous et al., 2014), both spousal caregivers and adult child caregivers experienced a sense of relationship loss with the survivor (Bastawrous et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2010; Saban & Hogan, 2012).

Loss of the spousal relationship was most difficult (Coombs, 2007; Winkler et al., 2014) as spousal caregivers expressed a loss of the partner they knew pre-stroke (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Barbic et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2010; Coombs, 2007; Saban & Hogan, 2012). In these instances, caregivers reported decreased intimacy and described the survivor as a stranger, as portrayed here: “So the feelings are…there's nothing left… I don't want him to touch me, I don't want him to be around me…and then to go to bed every night with a man that you don't…want to be there…” (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009, p. 120).

Adult children caregivers also identified changes in their relationship with their parent because of the stroke, including a ‘role-reversal’ as they were now caring for those who once cared for them (Saban & Hogan, 2012). Adult daughter caregivers focused mostly on their pre-stroke relationship their parent, despite noted changes in personality and relationships, and felt a “moral duty” to care for those who cared for them (Bastawrous et al., 2014, p. 1532). Adult daughters found that personality changes made it difficult to “[get] along”, but due to good pre-stroke relationships, they wanted to remain engaged in activities that allowed them to maintain a positive, close relationship post-stroke (e.g., speaking often and spending time together) (Bastawrous et al., 2014). Changes in the parent–child relationship contributed to feelings of sadness, loss and frustration (Bastawrous et al., 2014). For instance, many daughters experienced difficulty in the provision of intimate care (e.g., toileting and bathing) (Bastawrous et al., 2014).

Despite these negative consequences, the data also highlighted positive changes in relationships, including: improving communication (Green & King, 2009), increased sense of closeness with the survivor (Barbic et al., 2014; El Mastry et al., 2013; Saban & Hogan, 2012; Winkler et al., 2014), greater appreciation of the spousal relationship (Green & King, 2009), closer family relationships (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Barbic et al., 2014; El Masry et al., 2013; Green & King, 2009; Thomas & Greenop, 2008) and better meaning in friendships (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009).

3.4 Physical well-being

Caregiving as a full-time job was also evident in descriptions of the physical demands of care. Participants across studies described caregiving as a 24-hr routine of performing strenuous physical tasks for the stroke survivor. Some caregivers reported that survivors needed constant assistance with toileting and eating (Greenwood, Mackenzie, Cloud, & Wilson, 2010). Other demands included: bathing, dressing, delivering oral medication and putting the survivor to bed (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Chow & Tiwari, 2014; Winker et al., 2014).

Due to these demands, many caregivers experienced their own physical health challenges. Physical consequences related to fatigue (e.g., physical tiredness) (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Barbic et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2010; Greenwood et al., 2010; Kitzmüller et al., 2012; de Leon Arabit, 2008; O'Connel & Baker, 2004; Pierce, Thomas, Govoni, & Steiner, 2012; Thompson et al., 2004; Chow & Tiwari, 2014) and difficulties sleeping at night (Barbic et al., 2014; Lee & Mok, 2011; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Moore et al., 2002; Pierce et al., 2012) were most commonly reported. Some caregivers described having to get up to provide care (Bulley, Sheils, Wilkie, & Salisbury, 2010; Saban & Hogan, 2012; Smith et al., 2004; Winkler et al., 2014) and others reported being worried and checked on the survivor throughout the night (Green & King, 2009; Kitzmüller et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2004).

3.5 Psychosocial well-being

The caregiving situation affected many aspects of caregivers' psychosocial well-being. The aspects that comprise caregivers' psychosocial well-being included mental health (e.g., depression), emotional health (e.g., feelings, beliefs, attitudes) and social life (e.g., relationships).

Many caregivers reported a sense of responsibility or obligation to care, wherein the survivor was a spouse (Cecil et al., 2013; Gustafsson & Bootle, 2013; Johnson, 1998; Lee & Mok, 2011; de Leon Arabit, 2008), a parent (Bastawrous et al., 2014; Bocchi & Angelo, 2008; Danzl et al., 2013; Johnson, 1998; Subgranon & Lund, 2000) or a family member (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Pierce, 2001). Key aspects of the caregiving situation contributed to the psychosocial impact including caregivers' role motivating and encouraging people with stroke to promote further recovery (Gustafsson & Bootle, 2013), and managing the survivors' own emotional hardships, including suicidal ideation (Chow & Tiwari, 2014). In restructuring their lives, spousal caregivers reported a loss of independence (Cao et al., 2010; Green & King, 2009), autonomy (Green & King, 2009) and self-identity (Pierce et al., 2012). The full-time nature of this role led caregivers to feel burnt out, (Cao et al., 2010; Winkler et al., 2014), anxious (Barbic et al., 2014; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Thomas & Greenop, 2008; Chow & Tiwari, 2014; Winkler et al., 2014), depressed (Barbic et al., 2014; Bulley et al., 2010; Ghazzawi, Kuziemsky, & O'Sullivan, 2016; Thomas & Greenop, 2008; Chow & Tiwari, 2014) and frustrated (Bastawrous et al., 2014; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Winkler et al., 2014). Due to changes in relationships, many caregivers expressed loneliness (Saban & Hogan, 2012; Thomas & Greenop, 2008; Chow & Tiwari, 2014) or social isolation (Chow & Tiwari, 2014). A sense of fear for the survivor was commonly reported (Kitzmüller et al., 2012), particularly a fear of another stroke (Bocchi & Angelo, 2008; Coombs, 2007; Smith et al., 2004) and fear related to safety when leaving the person with stroke home alone (Gosman-Hedström & Dahlin-Ivanoff, 2012; Green & King, 2009; Low, Roderick, & Payne, 2004). This fear and need to monitor the survivor further exacerbated the psychosocial challenges experienced by increasing levels of stress (Green & King, 2009; Thomas & Greenop, 2008).

3.6 Factors affecting physical and psychosocial well-being

A variety of factors affected caregiver health and psychosocial well-being, including caregiver characteristics, availability of support and severity of stroke survivor impairments. For example, caregivers who were older and had pre-existing health problems generally found caregiving more physically challenging (El Masry et al., 2013). Others described the inability to turn or lift the survivor due to limited physical strength (Bocchi & Angelo, 2008; Lee & Mok, 2011). In contrast, individuals with personality characteristics, such as patience and empathy (El Masry et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2002; Rodrigues et al., 2013), as well as those who maintained a positive outlook (Winkler et al., 2014), transitioned more easily into the demands of the caregiver role. Personal coping mechanisms, such as drawing on past experiences (Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Winkler et al., 2014) and religion (Bocchi & Angelo, 2008; Cecil et al., 2013; Coombs, 2007; Danzl et al., 2013; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Pierce, 2001; Thompson et al., 2004) also made challenges more manageable.

Another aspect impacting caregivers' psychosocial experiences was the support available. Caregivers emphasised the importance of information and education (Cecil et al., 2013; El Masry et al., 2013; Saban & Hogan, 2012), training with physical care demands (Cobley, Fisher, Chouliara, Kerr, & Walker, 2013; Rodrgiues et al., 2013), and emotional and social support (Barbic et al., 2014) from clinicians to improve their health and well-being. Caregivers receiving relief from informal (e.g., family members and friends) support highlighted the value of assistance with performing housework (Low et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2004; Winkler et al., 2014), caring for the survivor (Coombs, 2007; Moore et al., 2002; Winkler et al., 2014) and offering psychosocial support (Van Dongen, Josephsson, & Ekstam, 2014; Low et al., 2004; Thomas & Greenop, 2008; Winkler et al., 2014). In contrast, caregivers lacking support were unable to take respite, and felt overwhelmed (Bastawrous et al., 2015) and isolated (Greenwood et al., 2010).

The demands of the caregiving situation were also dependent on survivor characteristics. More severe impairments were associated with greater experiences of caregiver burden and distress (Cao et al., 2010). Particularly, caregivers experienced challenges with survivor impairments in communication (Bakas et al., 2002; Bastawrous et al., 2014; Winkler et al., 2014), mobility (El Masry et al., 2013), and cognition and behaviour (El Masry et al., 2013; Gosman-Hedström & Dahlin-Ivanoff, 2012; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Smith et al., 2004).

3.7 Strategies to improve caregiver health and psychosocial well-being

Caregivers discussed strategies to enhance their physical health and psychosocial well-being. For instance, caregivers believed that more personal attention could improve health and well-being outcomes, as they recounted feelings of neglect by clinicians due to their exclusive focus on survivors (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Bakas et al., 2002), and described feeling the same sense of neglect from their friends and family (Saban & Hogan, 2012). Within their reflections, caregivers also suggested the need for respite to periodically escape from the relentless demands of the caregiver role (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Barbic et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2010; Lee & Mok, 2011). This short-term relief was recognised as a necessary component in alleviating stress (Cao et al., 2010) and maintaining caregiver resilience (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009) and well-being (O'Connell & Baker, 2004).

Despite the value of social support services (e.g., respite, peer support), caregivers reported barriers to access. Common barriers included lack of awareness of available services (Danzl et al., 2013; Saban & Hogan, 2012), unwillingness to seek support (Bakas et al., 2002; Bocchi & Angelo, 2008; Gosman-Hedström & Dahlin-Ivanoff, 2012) health insurance or financial restrictions, (Moore et al., 2002; Winkler et al., 2014) and geographic location (i.e., services or resources not available in their area) (Cecil et al., 2013; Danzl et al., 2013; de Leon Arabit, 2008; Low et al., 2004).

Caregivers called for a re-examination of current services to meet the challenges experienced by diverse caregiving populations, for example, those of young spousal caregivers (El Masry et al., 2013). Interventions providing psychological and financial support, as well as training in post-stroke care can also elevate some of the burden caregivers face (Pesantes, Brandt, Ipince, Miranda, & Diez-Canseco, 2017).

4 DISCUSSION

This review aimed to obtain an in-depth understanding of factors that affect caregivers' health (physical and psychosocial well-being) and, thus, the sustainability of family caregiving, by synthesising available qualitative literature. Using a qualitative meta-synthesis approach, one overarching concept arose: ‘caregiving is a full-time job’ that results in caregivers restructuring their lives, including changes to relationships. As a result, caregivers' physical health and psychosocial well-being can be compromised. This review also identified aspects of the caregiving situation associated with health and psychosocial well-being and strategies that could improve health outcomes.

Previous studies have alluded to the concept of caregiving being onerous (Bäckström &Sundin, 2010Cao et al., 2010; Coombs, 2007; Moore et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2004). The findings of this review add to our understanding of the complexity of this caregiving occupation, emphasising that the role of caregiving goes beyond the physical and psychosocial demands of providing care, and involves taking on new roles and responsibilities, in addition to pre-existing ones. The implications associated with caregiving for people with stroke, full time, was reported in different ways including the need to restructure the caregiver's personal life and relationship with the care recipient, as caregiving activities may supersede or reduce caregivers' involvement in other valued activities. These implications represent the challenges stroke caregivers face in maintaining a sense of normalcy and personal life outside of caregiving. Additional research is needed to further explore the needs of caregivers to support participation in valued activities.

Transitioning to providing care was a major adjustment in the caregivers' lives that can have implications for health and well-being. This finding is similar to previous reviews, which have described some of the experiences commonly encountered by caregivers, such as changes in roles and relationships (Greenwood et al., 2009; McKevitt et al., 2004). Previous reviews, however, have not explored the consequences of these experiences on health and well-being. As demonstrated in our review, the high demands of caregiving impacted caregivers' lives physically and psychosocially. Physical consequences were largely related to fatigue (e.g., physical tiredness) (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009; Barbic et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2010; Greenwood et al., 2010; Kitzmüller et al., 2012; de Leon Arabit, 2008; O'Connel & Baker, 2004; Pierce et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2004; Chow & Tiwari, 2014). Changes in relationships with their care recipient resulted in a profound sense of loss and emotional challenges for caregivers, which manifested to deeply affect many aspects of their lives and well-being, such as a lack of intimacy between spouses (Bäckström & Sundin, 2009) and frustration between children and parents (Coombs, 2007). Caregivers' experiences with the changes in daily living and changes in relationships suggest that caregivers find it difficult to balance the crossover that occurs between their role as caregiver and their role as a spouse or child. Results also highlight some of the positive changes in relationships for caregivers (e.g., improved communication (Green & King, 2009). These findings indicate the importance of exploring both negative and positive changes to gain a better understanding of the well-being of family caregivers. Interventions to support caregivers' emotional needs or well-being over time should focus on connecting them with others who have experienced role changes and loss in relationships or allow them to talk about these changes.

Our results highlight caregivers' needs for respite from the caregiving situation. While, the current literature on respite care is broad, the overall goal of respite care is to alleviate caregiver burden by temporarily relieving caregivers of their duties (Gilmour, 2002). American national guidelines advocate for an individualised approach to respite (Edgar & Uhl, 2011). However, research by Pinquart and Sörensen (2003) found that respite care may not alleviate dementia caregivers' psychosocial response to the requirements of their role as caregivers. Pinquart and Sörensen's (2003) study suggests that respite services may not have a lasting impact on caregiver burden once the individual's respite service period comes to an end. To help further support caregivers' well-being, our findings suggest that respite services should also be encouraged to give caregivers time to participate in meaningful occupations, social roles and relationships. Examples of ways respite services can do so is by combining respite with relationship counselling (Kepic, Randolph, & Hermann-Turner, 2019; Robinson-Smith, Harmer, Sheeran, & Bellino Vallo, 2016), increased education (Ahmed, El-Amin, Ahmed, Alostaz, & Khalid, 2015; Allison, Evans, Kilbride, & Campbell, 2008; Danzl et al., 2016; Reed, Harrington, & Duggan& Wood, 2010) or training about accessing psychosocial support (Grant et al., 2006; Hart, 1999; Martinsen, Kirkevold & Sveen, 2015).

4.1 Limitations

The review had some limitations. Although articles with varying origins and participant characteristics provided insight into a variety of caregiver experiences, the review only included articles published in English. As a result, findings may not represent the cultural diversity of caregiving experiences. Furthermore, as this study included only published, peer-reviewed studies, relevant research in grey literature may not have been identified. Additionally, the role of quality assessments of qualitative studies remains contested (Carroll & Booth, 2015;), thus the use of the CASP may not be appropriate to evaluate qualitative studies that differ in epistemological and philosophical paradigms (Barbour, 2001). It is possible that the varying theoretical unpinning used in each of the qualitative studies may have influenced the types of qualitative questions asked in the studies and the findings of this qualitative body of literature. While, the role of quality assessments of qualitative studies remains controversial (Carroll & Booth, 2015; Tong et al., 2012), all of the qualitative studies included in our review employed an appropriate methodology and research approach to meet their study aims. Further qualitative studies examining caregivers' health and well-being are encouraged to be more explicit in their reporting of recruitment methods and the relationship between the researcher and participants.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Caregiving is a full-time job, impacting various aspects of caregivers' health and well-being. This study identified some of the potential factors that may interact to facilitate a caregiver's performance in this role and some of the broad caregiving needs that remain unmet. Clinicians should provide support to minimise the physical and psychosocial consequences of caregiving by addressing the factors that affect caregiver health. Future researchers may build upon existing literature and further distinguish the impact on caregiver health along the care continuum (Cameron & Gignac, 2008; Cameron et al., 2014; Cameron, Naglie, Silver, & Gignac, 2013), contributing to the design and provision of timely support to improve health outcomes. In conclusion, this review found caregiving to be a full-time job that led to restructured lives, altered relationships, and physical and psychosocial challenges. This review also suggests that contextual factors, including unmet needs, play a role in how, and to what extent, physical and psychosocial challenges are experienced.