Informal caregivers’ views on the division of responsibilities between themselves and professionals: A scoping review

Abstract

This scoping review focuses on the views of informal caregivers regarding the division of care responsibilities between citizens, governments and professionals and the question of to what extent professionals take these views into account during collaboration with them. In Europe, the normative discourse on informal care has changed. Retreating governments and decreasing residential care increase the need to enhance the collaboration between informal caregivers and professionals. Professionals are assumed to adequately address the needs and wishes of informal caregivers, but little is known about informal caregivers’ views on the division of care responsibilities. We performed a scoping review and searched for relevant studies published between 2000 and September 1, 2016 in seven databases. Thirteen papers were included, all published in Western countries. Most included papers described research with a qualitative research design. Based on the opinion of informal caregivers, we conclude that professionals do not seem to explicitly take into account the views of informal caregivers about the division of responsibilities during their collaboration with them. Roles of the informal caregivers and professionals are not always discussed and the division of responsibilities sometimes seems unclear. Acknowledging the role and expertise of informal caregivers seems to facilitate good collaboration, as well as attitudes such as professionals being open and honest, proactive and compassionate. Inflexible structures and services hinder good collaboration. Asking informal caregivers what their opinion is about the division of responsibilities could improve clarity about the care that is given by both informal caregivers and professionals and could improve their collaboration. Educational programs in social work, health and allied health professions should put more emphasis on this specific characteristic of collaboration.

What is known about this topic

- The European discourse on informal care aims to diminish the reliance on government responsibility and to strengthen the norm of providing care by relatives.

- Informal caregivers are not always satisfied with their collaboration with professionals.

- Little is known about the opinion of informal caregivers about division of responsibilities between themselves and professionals.

What this paper adds

- Research shows roles of informal caregivers and professionals are not always discussed and division of responsibilities sometimes seems unclear.

- In the reviewed papers, acknowledging the role of informal caregivers and attitudes such as professionals being open, proactive and compassionate seem to facilitate collaboration.

- A good relationship between informal caregivers and professionals seems essential for clear distribution of responsibilities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many Western countries are currently implementing major reforms in long-term care. There are cutbacks in residential and professional care and as a result more attention is given to (enhancing) informal care. The current normative discourse on informal care aims “to weaken the reliance on government responsibility as care provider and to strengthen the norm of providing care to close relatives as well as to non-kin” (Broese van Groenou & de Boer, 2016). Despite the diversity in long-term care policies, common developments like highlighting the position of caregivers and encouraging their legally recognised status are observed throughout Europe (Triantafillou et al., 2010).

One third of the European population spends time giving informal care, in other words, looking after or giving help to family members, friends, neighbours or other acquaintances because of health reasons (Verbakel, Tamlagsrønning, Winstone, Erlend, & Eikemo, 2017). In this article, we label people giving informal care as “caregivers”; those who give care within their profession are referred to as “professionals.” In complex care and long-term care situations informal care is often combined with help from professionals (Jacobs, Broese van Groenou, de Boer, & Deeg, 2014). The prevalence of such mixed care networks is likely to increase due to the increased number of frail adults and elderly people living in the community. In these care situations collaboration between caregivers and professionals and the division of care responsibilities are important issues. Insights into normative beliefs of caregivers on the role collectively financed care services play increases our understanding of how to establish a good combination of formal and informal care.

One line of research about government involvement in care for frail people is public opinion research. The study of Daatland and Herlofson (2003) shows that citizens’ preferences for sources of long-term care vary between countries, and that these preferences reflect family care and social policy traditions. Van den Broek, Dykstra, and van der Veen (2015) investigated the care ideals of Dutch citizens. In the early twenty-first century, a shift has taken place towards an ideal in which state involvement in the provision of care is greatly valued and informal care is not. This shift suggests a discrepancy between Dutch long-term care policy and Dutch citizens’ normative beliefs. However, the authors also indicate that normative beliefs about easier forms of care may differ from normative beliefs about more demanding forms of care (Van den Broek et al., 2015). Specifically for elderly care there is evidence that public opinion is shifting in the same direction as the Dutch government aims in its care policy. A shift towards elderly care being seen as the primary responsibility of the family has taken place (Verbakel, 2014).

Although these studies provide fruitful information about the public opinion of citizens on the governmental care for frail people, we need more insight into the opinion of caregivers themselves on the division of responsibilities between local or national governments and citizens or, more specifically, between formal and informal care. In the discussion about what caregivers are able and willing to do, little attention is given to their opinion about the division of care responsibilities and underlying ideals which form these ideas (Beneken Genaamd Kolmer, Tellings, & Gelissen, 2008; Verbakel, 2014).

Another topic of research focuses on the collaboration between caregivers and professionals. Studies show that caregivers are not always satisfied with their collaboration with professionals (Carpentier, Pomey, Contreras, & Olazabal, 2008; McPherson, Kayes, Moloczij, & Cummins, 2013; Ward-Griffin & McKeever, 2000; Zwart-Olde, Jacobs, Broese van Groenou, & van Wieringen, 2013). Having a shared meaning of the relationship and the situation is important in order to achieve a good collaboration. Different expectations, attitudes and standards play a role in this (Nies, 2017).

It is important to gain a better understanding of collaboration between caregivers and professionals because it may hamper a fruitful caregiving process and the quality of care. There are indications that caregivers’ dissatisfaction about the collaboration between themselves and professionals can contribute to a higher burden, which may even lead to drop out (Williams, Wang, & Kitchen, 2016; Wittenberg, Kwekkeboom, & de Boer, 2012). To make sure caregivers can keep on providing care to their loved ones, risks like overburden should be reduced. Professionals must therefore adequately address the needs and wishes of caregivers. Working together with caregivers often is not the first focus of professionals who aim to help a care recipient who, for example, suffers from a chronic illness, is mentally disabled or has psychiatric problems.

As little is known about the caregivers’ views on their collaboration and division of tasks with professionals, we explore this issue in a scoping review. This review aims to investigate and describe what is known about the views of caregivers on the division of care responsibilities between citizens, governments and professionals, and to what extent caregivers think professionals take these views into account whilst collaborating with them. In this study all kinds of professionals are included, varying from professionals working in governments to professionals who work within care organisations.

2 METHODS

There are several ways to undertake a review of the literature. A scoping review is a technique to “map” relevant literature in the field of interest. Compared to the more traditional systematic review, a scoping review tends to address broader topics where many different study designs might be applicable and is less likely to address very specific research questions or to assess the quality of included studies (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brien, 2010). Given the breadth of purpose of our study, it was decided to carry out a scoping review using the framework of Arksey and O'Malley (2005). This framework is commonly used and provides a good methodological foundation (Levac et al., 2010).

The review focuses on research findings in the area of the division of care responsibilities between governments, professionals and caregivers. We wanted to identify all relevant literature regardless of study design. The framework contains five stages and an additional stage: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). The additional and optional stage, consultation, is in this case not performed.

After the aim of the research was identified, we considered which aspects of the research were particularly important. This is part of stage 1 of the framework. Together with a librarian (J.S.) we identified the key concepts of the scoping review: caregivers, responsibility and either government(s) or care professionals. Because this was a scoping review, the research question and the corresponding search strategy were broad (Armstrong, Hall, Doyle, & Waters, 2011). At the very minimum, our results had to be about caregivers and responsibility. Because this generated too many results, the search set was narrowed down by (1) publications that mentioned policy or government(s) or (2) publications where professionals were explicitly mentioned.

In stage 2, the librarian worked with us to decide which databases to search, and to formulate a search strategy including several synonyms for each key concept. Based on the screening of preliminary results with separate search terms, we carefully tested our selection of search terms for every key concept, optimising the number of relevant articles and excluding some of the noise in the results. The final search strategy was developed in and used to search PsycINFO. After that, the librarian converted the search strategy for the other databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts and Web of Science. We searched for articles published between 2000 and September 1, 2016, written in English. The year 2000 was chosen because we aimed to focus on publications about the division of care responsibilities in modern welfare state regimes, where welfare arrangements have been changing in recent years. It is these changes that make the question of what caregivers think about the division of care responsibilities more urgent. We also checked the bibliographies of the studies that were selected after screening the results from the systematic search, to ensure we would not miss any relevant studies in our scoping review. This did not result in including additional articles.

Stage 3 is study selection. The inclusion criteria were determined post hoc, based on increasing familiarity with the literature, and were then applied to all the identified references by the first two authors (Y.W. and R.K.). Inclusion criteria were (1) the paper should be about situations where caregivers and professionals meet, (2) the paper should focus on the opinion of the caregiver and (3) the research described in the papers should be executed in Western countries. This last criterion entails that we only included papers from modern, industrial, capitalist countries which share a culture derived from European civilisation with a high level of prosperity with several welfare arrangements, based on common fundamental political ideas regarding democracy and human rights.

It turned out that a lot of papers were based on the opinion of professionals instead of the opinion of caregivers. Based on the inclusion criteria, these papers were excluded. We also excluded editorials, columns and book reviews. Doubt on in/exclusion criteria was resolved by discussion between Y.W. and R.K.

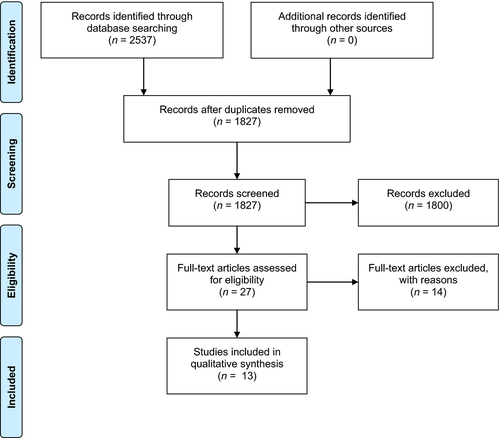

After this first screening, the full text of the selected articles was read to decide whether or not they should be included in the scoping review. Papers that seemed to meet all inclusion criteria, but caused doubt due to ambiguities were also read. Of the 1,827 references, 27 articles were read to decide whether all inclusion criteria were met. Finally, after a debate with the other authors (A.V. and A.B.), 13 articles were selected to include in this scoping review (see Figure 1). All included papers were published in peer reviewed journals.

In stage 4, charting the data, relevant information from the included articles was collected. We (Y.W. and R.K.) extracted general information: author(s), year of publication, study location, aim, methodology and study population (see Table 1). To show that the selected countries are characterised by specific welfare arrangements, we added a column in which the welfare state regime of the country is described.

| Author(s), year | Title | Study location | Aim | Design and method(s) | Study population | Welfare state regimea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stephan et al. (2015) | Successful collaboration in dementia care from the perspectives of healthcare professionals and informal carers in Germany: results from a focus group study. | Germany. | To explore the views of healthcare professionals (HCP) and caregivers of persons with dementia with regard to successful collaboration (1) between HCP and caregivers and (2) among HCP themselves, and to describe the factors that impede or facilitate collaboration. | Qualitative.Separate focus groups with HCP and informal carers. | HCP working in different dementia care settings (n = 13) and caregivers of persons with dementia in different stages of the disease (n = 17).Living situation of the person with dementia: at home or in a nursing home. Some of the persons with dementia were deceased. | Conservative. |

| Ayalon et al. (2013) | Family caregiving at the intersection of private care by migrant home-care workers and public care by nursing staff. | Israel. | To examine the changing roles of family members in the care of their hospitalised relatives and to attempt to define the relationship between family members and the other paid caregivers in that setting: nursing personnel and migrant home-care workers. | Qualitative.Structured interviews. | Hospitalised patients aged 65 years or older (n = 17), live-in migrant home-care workers (n = 20), primary caregivers (n = 16) and nursing personnel (n = 20). | - |

| Funk and Stajduhar (2011) | Analysis and proposed model of family caregivers’ relationships with home health providers and perceptions of the quality of formal services. | Canada. | To explore family caregivers’ accounts of their relationships and experiences with home-care nurses when caring for a dying family member at home and to draw on these data, supplemented by previous research, to develop a model to enhance caregivers’ relationships and satisfaction with home health services. | Qualitative.Ethnographic, qualitative interview. | Caregivers who cared for a dying family member at home (n = 26). | Liberal. |

| Rapaport et al. (2006) | Carers and confidentiality in mental healthcare: considering the role of the carer's assessment: a study of service users’, carers’ and practitioners’ views. | United Kingdom. | To identify good practice in professionals sharing information with caregivers with a view to developing a synthesised model. Although the aim derives from the ethical standpoint of professionals providing information, the research also encompassed the aspect of caregivers sharing information with professionals on the basis that information sharing usually involves two-way communication. | Mixed methods.Questionnaires, semi-structured interviews and group events. | A questionnaire specifically designed for service users (n = 168), caregivers (n = 525), professionals (n = 212) and carer support workers (n = 89). Semi-structured stakeholder interviews (n = 34). Group events comprising stakeholder groups (one of service users, three of caregivers, one of professionals) and two workshops involving service users, caregivers and professionals. | Liberal. |

| Wiles (2003) | Informal caregivers’ experiences of formal support in a changing context. | Canada. | To explore what it is like for caregivers looking after an elderly person at home to find out about, access and use formal community support. To explore in detail the situated experiences of these caregivers rather than to generate a representative sample. A key aspect of the study was to understand the experiences of people who were not using formal support services as well as those who were. | Qualitative.Semi-structured in-depth interviews. | Self-identified family caregivers looking after an elderly person at home (n = 30).Living situation of the care recipient at the time of the interview: co-resident of the caregiver (23), in an institution (5) or in another household (2). | Liberal. |

| Kirk (2001) | Negotiating lay and professional roles in the care of children with complex healthcare needs. | United Kingdom. | To explore parents’ experiences of caring for a technology-dependent child and of the professionals supporting them in the community. | Qualitative.In-depth interviews. | In-depth interviews with parents caring for a technology-dependent child (n = 33) in the family home and with professionals at their place of work (n = 44). | Liberal. |

| Bove et al. (2016) | Undefined and unpredictable responsibility: a focus group study of the experiences of informal caregiver spouses of patients with severe COPD. | Denmark. | To explore how spouses of patients with severe COPD experience their role as caregiver spouses. | Qualitative.Focus groups. | Spouses of patients with severe COPD (n = 22).Living situation of the care recipient: co-resident of the caregiver. | Social democratic. |

| Røthing et al. (2015) | Family caregivers’ views on co-ordination of care in Huntington's disease: a qualitative study | Norway. | To explore the experiences and expectations of family caregivers for persons with Huntington's disease concerning collaboration with healthcare professionals. | Qualitative.Semi-structured interviews. | Family caregivers for persons with Huntington's disease (n = 15). | Social democratic. |

| Egdell (2013) | Who cares? Managing obligation and responsibility across the changing landscapes of informal dementia care. | United Kingdom. | To examine how caregivers of people with dementia negotiate their caring roles. It looks at the socially situated decisions that caregivers make regarding their caregiver role, and argues that these are also spatially situated negotiations. | Qualitative.Semi-structured interviews. | Caregivers of people with dementia who were in different caregiving situations (n = 13).Living situation of the care recipient: co-resident of the caregiver (3), living in their own house (5), in a nursing home (1) or the persons with dementia was deceased (4). | Liberal. |

| Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010) | A desire to be seen.Family caregivers’ experiences of their caring role in palliative home care. | Sweden. | To explore how the caregivers of a dying relative in palliative home care experienced their caring role and support during the patient's final illness and after death. | Qualitative.Interviews. | Family caregivers (n = 13) of patients admitted to primary healthcare—based palliative home care; the patient had died 3–12 months since admission. | Social democratic. |

| Toscan et al. (2012) | Integrated transitional care: patient, informal caregiver and healthcare provider perspectives on care transitions for older persons with hip fracture. | Canada. | To investigate care co-ordination for older hip fracture patients from multiple perspectives, including patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers to determine the core factors related to poorly integrated care when patients transition from one care setting to another. | Qualitative.Semi-structured interviews. | Older hip fracture patients (n = 6), caregivers (n = 6), healthcare providers (case managers, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and a general practitioner) (n = 18). In total, 45 individual interviews were conducted. | Liberal. |

| Andrew et al. (2009) | Perceptions of mental health professionals and family caregivers about their collaborative relationships: A factor analytic study. | Australia. | To explore the nature of professional–caregiver collaboration by applying the Henneman, Lee and Cohen (1995) framework to routine professional–caregiver relationships, specifically asking: (a) what key dimensions are evident in the perceptions of collaboration by both mental health professionals and family caregivers of adults with severe mental health problems; and (b) which collaboration dimensions best predict professionals’ and caregivers’ perceptions of overall collaboration. | Mixed methods.Focus groups followed by a questionnaire. | Focus groups with family caregivers of people with mental health problems (n = 19) and mental health professionals (psychologist, psychiatrist and social worker) (n = 3).After that, caregivers (n = 270) and professionals (clinical staff employed by acute and non-acute public adult mental health services) (n = 240) completed a questionnaire.Living situation of the care recipient (based on the questionnaire): living with the caregiver (47%), living in own accommodation (33%), other (20%). | Liberal. |

| Ryan and Scullion (2000) | Family and staff perceptions of the role of families in nursing homes. | Northern Ireland. | The study had three main aims:

|

Mixed methods.Questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. | Questionnaire: family caregivers caring for someone in a nursing home (n = 44) and nursing home staff (n = 78).Interviews: family caregivers (n = 10) and nursing home staff (n = 10). | Liberal. |

- a According to the Esping-Andersen welfare state typology (1990), as described in Bambra (2007).

As Levac et al. (2010) described, this stage of Arksey and O'Malley's framework does not provide enough detailed information to analyse the outcomes and important results properly. Therefore, we decided to use the method of thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden (2008) to further analyse the data. This method was chosen because all included studies were partly or entirely characterised by a qualitative research design. First, we inductively created codes in the “results” or “findings” section of each included study to capture the meaning and content of each finding (except for the study of Andrew, Farhall, Ong, and Waddell (2009); we analysed the “discussion” section because that was the section where their results were interpreted). Second, we grouped these codes into a tree structure to organise the descriptive themes. Third, we arrived at a qualitative synthesis by defining overarching analytical themes that described all of the initial descriptive themes (Thomas & Harden, 2008) (see Table 2). While charting and analysing the data, we used MAXQDA Analytics Pro 12.

| Stephan et al. (2015)/Germany | Ayalon et al. (2013)/Israel | Funk and Stajduhar (2011)/Canada | Rapaport et al. (2006)/United Kingdom | Wiles (2003)/Canada | Kirk (2001)/United Kingdom | Bove et al. (2016)/Denmark | Røthing et al. (2015)/Norway | Egdell (2013)/United Kingdom | Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010)/Sweden | Toscan et al. (2012)/Canada | Andrew et al. (2009)/Australia | Ryan and Scullion (2000)/Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division of responsibilities | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Informal caregiver is responsible for… | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Formal and informal care think the same/different about responsibilities | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Unclear responsibilities | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Diversity | x | x | |||||||||||

| Role negotiation | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Boundaries between formal and informal care roles | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Context for role negotiation | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Barriers for role negotiation | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Recognition of caregiver role/involvement is important | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Support doesn't meet caregivers’ needs | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Collaboration | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Collaboration, facilitator | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Collaboration, challenge/barrier | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

The fifth stage of the framework involves providing an overview of all articles reviewed. In order to describe our findings, the overarching analytical themes were used. Unfortunately, the included papers did not reveal caregivers’ opinions about division of responsibilities between themselves and governments. Therefore, this review focuses on division of responsibilities between caregivers and professionals.

3 FINDINGS

3.1 Methodological overview

Most of the 13 included articles (n = 10) described studies with a qualitative research design. The other articles described studies with a mixed methods design. The findings are based on either in-depth or (semi-)structured interviews (n = 10) or on focus groups (n = 3). The number of respondents in the qualitative studies varied between 6 and 34, with an average of 20 and a median of 17. In most studies, the care recipient was a spouse or a child of the caregiver. In almost all included studies, respondents were caregivers of persons with different kinds of problems or diseases: people with dementia (2), hospitalised patients (2), people with terminal diseases (2), people with mental problems or illnesses, elderly people, technology-dependent children, patients with severe COPD, patients with Huntington's disease, or elderly people with hip fracture. In two studies, the care recipient received residential care and in four studies, the care recipient was living at home, either with or without the caregiver. In the other studies, the care recipient's living situation was not explicitly described or it varied among the respondents or over time.

Papers that were included covered studies in Europe (Germany, United Kingdom (3), Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Northern Ireland), Asia (Israel), North America (Canada (3)) and Australia (see Table 1).

3.2 Overarching outcomes

Three overarching analytical themes were defined by the authors to synthesise relevant descriptive subthemes: (1) Division of responsibilities, (2) Role negotiation and (3) Collaboration. Table 2 shows these overarching analytical themes and their initial descriptive subthemes, and gives an overview of which themes were discussed in the included studies. With division of responsibilities we refer to views about the division of responsibilities between caregivers and professionals, for organising care for and giving help or care to the care recipient. We investigate what is written about caregivers’ views on the division of responsibilities, including to what extent caregivers and professionals think the same about this subject. Also, we focus on what is described about unclear responsibilities and about the importance of assessing cultural contexts in understanding collaboration. We define role negotiation as the discussion attributing everyone's responsibility in organising care or giving help or care to the care recipient. We here look into what is written about boundaries between formal and informal care roles, the context and barriers for role negotiation and the importance of involvement of the caregiver. Collaboration means that caregivers and professionals are somehow working together to organise parts of care for or give parts of help or care to the care recipient. This last theme concerns statements regarding facilitators and challenges or barriers for collaboration between caregivers and professionals.

In eight of the included studies, all three overarching analytical themes were addressed (see Table 2). This means that we used at least one of the descriptive subthemes to code presented information in the “results” or “findings” section. In four of the studies, two overarching analytical themes were addressed and in one study, only one overarching analytical theme was recognised.

Divisions of responsibilities is a theme that was given attention to in twelve included studies. In eleven studies, information was presented related to the theme role negotiation. Finally, 10 studies presented information about collaboration between caregivers and professionals.

The descriptive subthemes we recognised to a greater or lesser extent. Within the overarching analytical themes, the following subthemes were most frequently recognised: “Informal care is responsible for…” (10), “Recognition of the caregiver role/involvement is important” (8), “Collaboration, facilitator” (8), “Collaboration, challenge/barrier” (8) and “Context for role negotiation” (7).

3.2.1 Division of responsibilities

The first overarching analytical theme that was formulated to synthesise relevant descriptive subthemes is described as “division of responsibilities.” This theme was discussed in 12 of the 13 included studies. In this section, we focus on what caregivers think about how responsibilities between themselves and professionals should or could be divided.

In five articles, caregivers view care management as their primary responsibility (Ayalon, Halevy-Levin, Ben-Yizhak, & Friedman, 2013; Kirk, 2001; Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010; Stephan, Möhler, Renom-Guiteras, & Meyer, 2015; Toscan, Mairs, Hinton, & Stolee, 2012). In the study of Stephan et al. (2015) caregivers of people with dementia appear to be predominantly responsible for obtaining information on available services, organising professional care and transferring information among various healthcare providers. In another study, adult children of hospitalised care recipients portrayed themselves as being “in charge” of the entire caregiving arrangement, including arranging various healthcare providers (Ayalon et al., 2013). Røthing, Malterud, and Frich (2015) state that caregivers feel responsible to initiate increased healthcare services, which they felt should be initiated by health professionals.

Caregivers seem to try to manage care alone or with informal support as long as possible because of a desire to maintain independence, a sense of personal responsibility for caregiving, and pride. Caregivers do not want to be looked upon as passive victims of their role (Wiles, 2003). In Kirk's (2001) study, feelings of obligations and a strong desire to bring their children home even though they are technology-dependent turned out to be key motivating factors in acceptance of responsibility among adult caregivers. Bove, Zakrisson, Midtgaard, Lomborg, and Overgaard (2016) state that caregivers did not want to be deprived of responsibility, but sought support and knowledge of how to handle it correctly.

Other responsibilities that were felt by caregivers were described as dealing with practical and emotional caregiving problems (Egdell, 2013), to advocating for their loved ones (Toscan et al., 2012), physical presence and emotional care (Ayalon et al., 2013) and keeping company (Ryan & Scullion, 2000). Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010) described that caregivers feel the social responsibility to give the care recipient an impression of security and strength. In this study, caregivers also felt they were responsible for the patient's personal care and, sometimes, even medication. These caregivers helped relatives admitted to primary healthcare or in palliative home care. They felt an unspoken expectation from the care recipient that the caregiver should manage and take care of nursing and administering medication.

We sought to find to what extent caregivers and professionals had the same views on what should or could be the caregivers’ responsibility. In one of the included studies, caregivers and professionals had similar views on the caregivers’ responsibility. Nurses underlined the importance of family visits and upheld the same expectations for emotional care by caregivers: families can give emotional support when they come to see the care recipient. They don't have to do anything else (Ayalon et al., 2013). However, the same study showed different views on caregivers’ responsibilities. Professionals did not discuss the family members’ roles and hardly acknowledged the managerial aspects associated with the care.

According to Andrew et al. (2009) caregivers of people with mental health problems and, to a lesser extent professionals, tend to attribute responsibility for collaboration to the other party. In the study of Ryan and Scullion (2000), families caring for someone in a nursing home perceived that they had more involvement than perceived by professionals. Although caregivers perceived several tasks as shared, professionals believed only a few of these tasks were shared and saw the others as primarily their responsibility (Ryan & Scullion, 2000). According to Bove et al. (2016), caregivers of co-resident people with severe COPD experience an undefined and unpredictable multi-faceted role, with ambiguity about expectations from both their surroundings and health professionals, leading to a feeling of being used and misused and a concern that their strength would eventually run out.

Four studies mentioned that roles and responsibilities between caregivers and professionals are sometimes unclear (Egdell, 2013; Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010; Røthing et al., 2015; Toscan et al., 2012). Unclear responsibilities made it difficult for the caregivers to know what was expected of them (Røthing et al., 2015). Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010) stated that professionals being unclear about what they expected from caregivers led to a feeling of insecurity, and the caregivers felt isolated and vulnerable. Problems with communication and lack of guidance created feelings of frustration (Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010). According to Egdell (2013), caregivers have an uncertain role when the person with dementia they support moves into a nursing home and they have to reconcile the different expectations of their capabilities and renegotiate their role. Caregivers sometimes feel professionals have too great an expectation of the caregivers’ capabilities. In one study, uncertainty existed between caregivers of older hip fracture patients and professionals as to who is responsible for initiating communication about care and what the roles of others within the care network were (Toscan et al., 2012).

Two studies underlined the importance of assessing the cultural context in understanding caregivers. Social and cultural assumptions might cause different experiences and can be an explanation of why caregivers do not realise they can use support (Egdell, 2013). Often, caregiving responsibilities and obligations are framed in different ways (Egdell, 2013). Practices reflect social and cultural norms, as well as individual and family biography. Care decisions are situated in a web of social relations and individuals make difficult decisions about how they will balance competing demands. Rapaport, Bellringer, Pinfold, and Huxley (2006) also identified the importance of assessing the cultural context in understanding the caregivers needs. For example, caregivers of people with mental health problems who had a South Asian background felt services did not take account of their individual and cultural needs.

Summarising, caregivers see organising care and transferring information among various stakeholders as their own responsibility. In five of the included studies, caregivers view organising care as their primary responsibility. It seems that caregivers and professionals have different views of caregivers’ responsibilities. Professionals do not always discuss the caregivers’ roles. Sometimes, caregivers perceive that they have more involvement than perceived by professionals. According to caregivers, the division of responsibilities between caregivers and professionals is sometimes unclear. Some studies underline the importance of assessing the cultural context in understanding the collaboration between caregivers and professionals.

3.2.2 Role negotiation

The second overarching analytical theme that was formulated to synthesise relevant descriptive subthemes is “role negotiation.” Eleven of the included studies described information about this theme. In this section, we focus on the context in which role negotiation occurs.

Five articles addressed the negotiation of boundaries of the caring role. In Egdell's (2013) study, caregivers negotiated boundaries of the caring role in different ways by identifying when, where and from whom they expected support. Ideas of responsibility and obligation towards the care recipient were relevant in placing limits on the support they gave. Decisions reflected the legacy of previous relationships and caregiving experiences and may have been influenced by gender assumptions. In addition, some caregivers considered the limits of the support they were prepared to provide, whereas others negotiated whom they could expect to receive assistance from. Some carried the demands of care alone at home because they did not realise that they were entitled to support. Care in the home may be taken for granted. Caregivers may be expected to provide care without the support of professionals or others; those caring for someone in a nursing home have to negotiate their role. Sometimes, there is little negotiation of caregiving tasks among family members, and as a result individuals may provide care because of geographical closeness, gender or because no one else takes responsibility (Egdell, 2013). Kirk (2001) found that boundaries are not static: in response to changing needs, caregiving responsibilities continued to be transferred between caregivers and professionals. The individual caregivers’ preferences and willingness to undertake a given task determines where the boundary is drawn.

Both Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010) and Kirk (2001) underlined the importance of building a relationship between the caregivers and professionals when it comes to determining boundaries between their responsibilities. When caregivers managed to build a relationship with professionals, they experienced a clear distribution of responsibilities between professionals and themselves and felt involved in the care (Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010). The study of Andrew et al. (2009) shows that caregivers conceptualise their relationship with professionals in terms of the professionals’ and their own behaviour, rather than in terms of their mutual interaction. Caregivers in their study seemed broadly aware of the nature of their relationship with professionals, but less aware of the implicit processes via which this relationship had developed (Andrew et al., 2009). As Kirk (2001) described, when caregivers gain more experience in caring and interacting with professionals, they develop clearer views on the appropriate roles for them to take on themselves. In Kirk's study, caregivers were unable to foresee the reality of caring for a technology-dependent child with intensive needs. Appropriateness is judged in terms of whether caregivers felt it was in their child's or family's best interests. However, role boundaries were also determined by professionals’ assessment of caregivers’ ability to cope with caregiving.

Five studies show that sometimes, there is little room for discussion about the division of responsibilities (Egdell, 2013; Kirk, 2001; Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010; Ryan & Scullion, 2000; Toscan et al., 2012). For example, Egdell (2013) found that caregivers of people with dementia may not be asked about how, or if, they wish to remain involved in the care of a care recipient once they have moved into a nursing home. In another study, caregiving was described as “an obligation and something beyond discussion, and the participants had a distinct, loyal, ethical, social, and emotional way of talking about this” (Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010). Caregivers were sometimes assumed to take on formal care responsibilities. Caregivers often wished they had taken more control over the situation by being more assertive with their request for help and information (Toscan et al., 2012). Kirk (2001) found that it could be difficult for caregivers to counter professional expectations of their roles in the hospital context because of power asymmetries. They felt that parents were able to exercise a greater degree of power in the home than in the hospital environment. However, many caregivers found that being assertive in negotiating roles with professionals was not easy, even in the home (Kirk, 2001).

Six articles reveal other barriers for role negotiation. According to Egdell (2013), some caregivers were unable to make informed choices about the ways in which they provided care or negotiated their care-giving role because they did not know they could ask for formal support or that formal support was available. Sometimes, the communication focused on the care recipient, not the caregivers’ feelings or experiences (Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010). According to Kirk (2001), professional expectations and the lack of appropriately skilled professional care were a barrier to role negotiation. In another study, caregivers often felt intimidated or like a burden to the healthcare team when they required information or clarification on a particular aspect of care (Toscan et al., 2012). Toscan et al. (2012) also describe the unease and stress that is sometimes experienced by caregivers as a result of the increased reliance on informal care placed on them by the system.

Ayalon et al. (2013) did not describe barriers to role negotiation, but they did focus on barriers to fulfilling a caregiving role. Caregivers can experience cultural, practical or emotional barriers to fulfilling their caregiving role. Religious and cultural beliefs are identified as the main reason for lack of engagement in nursing care. Provision of physical care by adult children for their parent is sometimes a taboo or obstructed by fear. Practical barriers might be distance to a hospital or preoccupation with attending to daily routines. Past relationships might be emotional obstacles to engagement in care (Ayalon et al., 2013).

Five studies explicitly describe the importance of professional recognition of the caregivers’ role (Kirk, 2001; Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010; Rapaport et al., 2006; Røthing et al., 2015; Wiles, 2003). Recognition is viewed to be paramount and a key principle underpinning good information-sharing practice (Rapaport et al., 2006). Wiles (2003) describes the need to be involved and respected in decision-making. Caregivers looking after an elderly person at home find it easier to deal with professionals who are sensitive and responsive to their needs, and treat them with respect. However, four studies also show that professional recognition of the caregivers’ role is not always the case. For example, Bove et al. (2016) found out that caregivers felt powerless and abandoned by professionals. Professionals did not consider the caregivers to be experts or resources, and the caregivers expressed a strong desire to be informed and included in decisions. According to Egdell (2013), it is only when caregivers become part of the care system that their input is taken into account. In the study of Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010) caregivers felt invisible with a hope of being seen. The professionals were there for the care recipient, but very few asked about the caregivers’ situation. Caregivers sometimes felt underappreciated, and that made them take a step backwards.

Four studies show that support doesn't always meet the caregivers’ needs (Bove et al., 2016; Egdell, 2013; Røthing et al., 2015; Wiles, 2003). The inflexibility of services is often difficult for caregivers. They find that professionals are not able, willing, or allowed to perform what they regard as the most basic or potentially helpful tasks (Wiles, 2003). Bove et al. (2016) found in their study that caregivers experienced no or little support or acknowledgement from professionals. They said that they had to be proactive and forceful if they wanted contact with a professional during the patient's hospitalisation. The experience of being forced to act without knowledge and support was described as stressful and frustrating. According to Røthing et al. (2015), caregivers for persons with Huntington's disease described the need for professionals to understand how the illness of the patient could affect the family. This expectation was not always met.

In summary, it seems that boundaries between formal and informal caregivers’ roles and responsibilities are not static. In response to needs, caregiving responsibilities continue to be transferred between both parties. Ideas of responsibility may be relevant in placing limits on the support informal caregivers give. It seems to be important to build a relationship between the caregiver and professionals: when caregivers manage to build that relationship, they experience a clear distribution of responsibilities.

Multiple studies underline the importance of professional recognition of the caregivers’ role. Caregivers find it easier to deal with professionals who are sensitive to their needs and treat them with respect. However, studies show that sometimes there is little discussion about the division of responsibilities and recognition of the caregivers’ role is definitely not always the case.

3.2.3 Collaboration

The last overarching analytical theme that was formulated to synthesise descriptive subthemes is described as “collaboration.” Collaboration is a subject that came forward in ten of the thirteen included studies. In this section, we focus on facilitators and challenges or barriers for collaboration between formal and informal care.

In eight articles, factors that enhance good collaboration were described (Andrew et al., 2009; Funk & Stajduhar, 2011; Kirk, 2001; Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010; Rapaport et al., 2006; Røthing et al., 2015; Stephan et al., 2015; Wiles, 2003). An important facilitator seems to be showing respect to the care recipient and the caregiver, and acknowledging the role and expertise of the caregiver (Funk & Stajduhar, 2011; Rapaport et al., 2006; Stephan et al., 2015; Wiles, 2003). Support or contact should be tailored to the caregivers’ needs (Funk & Stajduhar, 2011; Stephan et al., 2015) and professionals should be sensitive and responsive to those needs (Wiles, 2003). Another important facilitator is found in the skills and attitudes of the professional. They should be open, patient, friendly, honest, approachable, proactive in seeking and maintaining contact with caregivers in order to realise good collaboration (Stephan et al., 2015). Funk and Stajduhar (2011), whose study is about caregivers who cared for a dying family member at home, describe compassionate, sensitive and empathic behaviour as important attributes. According to Andrew et al. (2009), caregivers consider the behaviours and attitudes of professionals to be more central to collaboration than their own.

In two articles, the importance of clear responsibilities is mentioned as a facilitator for good collaboration between formal and informal care (Røthing et al., 2015; Stephan et al., 2015). Linderholm and Friedrichsen (2010) described it the other way around: when caregivers managed to build a relationship with professionals, they experienced a clear distribution of responsibilities. Finally, consistency was described as facilitating good collaboration. A permanent contact person, continuity and long-term knowledge about family circumstances seem important in developing a good relationship between caregivers and professionals (Funk & Stajduhar, 2011; Kirk, 2001; Rapaport et al., 2006; Stephan et al., 2015; Wiles, 2003).

The included studies also showed challenges or barriers for good collaboration between caregivers and professionals. Two articles mentioned problems with communication (e.g. unclear information or miscommunication by the care recipient) as a barrier (Linderholm & Friedrichsen, 2010; Røthing et al., 2015). Wiles (2003), Toscan et al. (2012), Rapaport et al. (2006) and Stephan et al. (2015) wrote about the importance of recognising the caregiver's role. Inconsistency in recognising the most appropriate role of caregivers during transitions could hinder good collaboration (Toscan et al., 2012). When advice of caregivers is not considered, this is a barrier for good collaboration (Stephan et al., 2015).

Rapaport et al. (2006) mention perceptions about caregivers with different cultural backgrounds as a possible barrier, as well as language. Stephan et al. (2015) describe that late contact between caregivers and professionals can be a barrier. Caregivers sometimes have difficulties contacting professionals, primarily due to inner barriers or uncertainties. Finally, inflexible structures and services, as well as time restrictions and a lack of financial compensation, are also described as barriers for collaboration (Stephan et al., 2015).

In summary, acknowledging the role and expertise of the caregiver seems a facilitator of good collaboration between caregivers and professionals. The importance of clear responsibilities is also mentioned. Several attitudes of professionals are described as facilitators, such as being open and honest, proactive and compassionate. Inconsistency in recognising the most appropriate role of caregivers or assuming responsibility by professionals, as well as inflexible structures and services, can be barriers to good collaboration.

4 DISCUSSION

With this scoping review, we aimed to investigate and describe what is known about the views of caregivers on the division of care responsibilities between citizens, governments and professionals and the question of to what extent caregivers think professionals take these views into account during collaboration with them.

As none of the authors of the included papers gave explicit definitions of important concepts like collaboration or responsibilities, we have distinguished three aspects: division of responsibilities, role negotiation and collaboration. With regard to task division, an important finding is that caregivers view organising care and transferring information among various stakeholders about the care situation as their responsibility. There is, however, a lack of clarity in task division with professionals: caregivers do not always know what professionals expect from them and caregivers assume they have more involvement in caregiving than professionals think caregivers have.

As for role negotiation, the findings underline the importance of professional recognition of the caregivers’ role. When professionals are sensitive to the caregivers’ needs and treat them with respect, the collaboration between them could improve. Concerning collaboration, the context in which this takes place seems to be crucial. When the expertise of the caregiver is acknowledged and the division of responsibilities is clear, collaboration can work out fine. However, when structures of provision are inflexible or communication between professionals and caregivers is poor, these are obstacles for good collaboration.

The included studies were often not specifically focused on care recipients who received residential care or care in a home setting. However, it does seem that the care setting influences the way in which the caregiver is involved by professionals. Egdell (2013) found that caregivers may not be asked about how, or if, they wish to remain involved in the care of a care recipient once he or she moved into a nursing home. These findings suggest that in residential settings, it is even more difficult to negotiate the division of care responsibilities. These findings corroborate other research: caregivers who do not live with the care recipient at home deliberate less with professionals and are less satisfied with communication (Zwart-Olde et al., 2013).

In this scoping review, we tried to make sure research findings from studies performed in different countries were comparable as much as possible and at least useful for our following research. We did this by only including research performed in Western countries. Long-term care arrangements are different in several countries, but, as described in the introduction, common developments like highlighting the position of caregivers are recognised (Triantafillou et al., 2010). This scoping review gives an insight in the ways professionals take caregivers’ views into account during collaboration in several countries, but no general conclusions that apply to all Western countries can be drawn. Because of the low number of included papers, we could not differentiate research findings based on welfare state regimes.

In the papers included in this scoping review, little attention is given to underlying ideals which form ideas about the division of care responsibilities. Insights concern the practical division of care tasks between caregivers and professionals, but do not focus on the underlying ideals. Also, the papers did not reveal caregivers’ opinions on responsibilities of governments for providing care. In our future research, we want to find out what caregivers expect of both professionals and governments.

We also want to discuss the way we conducted this scoping review. As Arksey and O'Malley (2005) stated themselves, there is no definitive procedure for scoping the literature. The framework they describe turned out to be a useful method to perform our review. Combined with the method for thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden (2008), we were able to summarise and disseminate research findings in the area of division of care responsibilities. We now know which aspects are relevant when it comes to collaboration between caregivers and professionals according to the caregivers themselves.

Because scoping reviews intend to capture a broad range of research, regardless of design and quality (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Bastawrous, Gignac, Kapral, & Cameron, 2015), we chose not to execute a methodological appraisal. Although this might be a weakness of our study, it seems the common way to perform scoping studies.

A restriction of the framework of Arksey and O'Malley is its 4th stage: charting the data. The framework does not provide detailed information regarding how to analyse included outcomes (Levac et al., 2010). We overcame this weakness by using the method for thematic synthesis described by Thomas and Harden (2008). This turned out to be useful. A limitation might be that we only analysed the “results” or “findings” sections of included studies, which means we could have missed relevant information to better interpret the described results. One study was analysed in a different way. We analysed the “discussion” section of the study of Andrew et al. (2009), because that was the section where the results of their quantitative analysis were interpreted. The overall conclusions of each included study were not discussed in our scoping review (see Thomas & Harden, 2008).

As mentioned in our “methods” section, the last additional stage of the framework was not performed. We did not ask for consultation of stakeholders (e.g. caregivers and professionals) because a consultation was beyond the scope of our current research. We are going to use the review findings, combined with those from upcoming research, for in a later phase organising focus groups to discuss relevant insights.

4.1 Implications for practice and policy

Our scoping review reveals that good collaboration between caregivers and professionals consists of a clear division of responsibilities between them and that a good relationship between caregivers and professionals contributes to a clear distribution of responsibilities. Therefore, it seems necessary for professionals to build such a relationship and to discuss the division of responsibilities with caregivers. Asking caregivers what their opinion is about the division of responsibilities could improve clarity about the care that is given by both the caregiver and the professional and could improve their collaboration. Uncertainty can cause problems in the collaboration between formal and informal caregivers, such as increasing the burden on caregivers. It is also important for professionals to recognise and acknowledge the role and expertise of the caregiver. Working with and supporting caregivers is often not the first focus of the professional who aims to help a care recipient. This should change: with the current normative discourse on informal care (Broese van Groenou & de Boer, 2016) it becomes even more important to improve collaboration. To realise this, the educational programs of social work, health and allied health professions should put more emphasis on this specific characteristic of collaboration.

We think that knowledge about the possible differences in caregivers’ views on the division of care responsibilities and insight into ideals which form these views is needed so that professionals can adequately address caregivers’ needs and wishes with respect to the role of governments and professionals. This scoping review was a first step in this research. Further research is needed to investigate the exact opinions of caregivers about the division of care responsibilities more in-depth.

5 CONCLUSION

Based on the thirteen papers we reviewed, we conclude that good collaboration between caregivers and professionals consists of a clear division of responsibilities between them. However, roles of caregivers and professionals are not always discussed and the division of responsibilities sometimes seems unclear. Acknowledging the role and expertise of caregivers is important. A good relationship between caregivers and professionals contributes to a clear distribution of responsibilities and thus is necessary in order to realise good collaboration. To improve collaboration, professionals should build a relationship and explicitly discuss division of care responsibilities with caregivers. Social work, health and allied health professions should give more attention to this subject in their educational programs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Faridi van Etten-Jamaludin, clinical librarian at the Academic Medical Center (AMC) Amsterdam, the Netherlands for thinking along during the first phase of this scoping review.