Rural residents' perspectives on the rural ‘good death’: a scoping review

Abstract

The ‘good death’ is one objective of palliative care, with many ‘good death’ viewpoints and research findings reflecting the urban voice. Rural areas are distinct and need special consideration. This scoping review identified and charted current research knowledge on the ‘good’ rural death through the perspectives of rural residents, including rural patients with a life-limiting illness, to identify evidence and gaps in the literature for future studies. A comprehensive literature search of English language articles (no date filter applied) was conducted in 2016 (2 January to 14 February) using five library databases. Reference lists of included articles, recent issues of eight relevant journals and three grey literature databases were also hand-searched. Twenty articles (for 17 studies and one systematic review) were identified after a two-phase screening process by two reviewers, using pre-determined inclusion criteria. Data from each study were extracted and charted, analysed using a thematic analysis of the included articles' content, and with a quantitative analysis of the scoping review. These papers revealed data collected from rural patients with a life-limiting illness and family caregivers, rural healthcare providers, the wider rural community, rural community leaders and rural health administrators and policy makers. Rural locations were heterogeneous. Residents from developed and developing countries believe a ‘good death’ is one that is peaceful, free of pain and without suffering; however, this is subjective and priorities are based on personal, cultural, social and religious perspectives. Currently, there is insufficient data to generalise rural residents' perspectives and what it means for them to die well. Given the extreme importance of a ‘good death’, there is a need for further studies to elicit rural patient and family caregiver perspectives.

What is known about this topic

- The ‘good death’ is a key objective of palliative care.

- Current viewpoints and research about ‘good’ deaths reflect the urban voice.

- Rural areas are distinct and as such need to have special consideration.

What this paper adds

- Rural residents in both developed and developing countries report similar themes for a ‘good death’ as urbanites.

- Rural perspectives are subjective and dependent on rural context.

- Highlights the need for more research regarding rural patient and family caregiver perspectives on what it means to die well.

Introduction

Death is an individualised experience with cultural, religious and political values and beliefs influencing the quality of dying. (Cottrell & Duggleby 2016). The ‘good death’ is one of the main objectives, if not the sole aim, of palliative care. It is a dynamic concept whose meaning has changed over time in line with urbanisation and advances in medical technologies (Aries 1974, Kellehear 2008). Some argue the contemporary notion of the ‘good death’, fostered by the hospice/palliative movement, is idealised and ‘limits spontaneity’ (Cottrell & Duggleby 2016). Historically, death and dying have moved from an open public activity at home to a more private and institutionalised process, hidden away in hospitals or other institutions such as nursing homes (Gomes & Higginson 2008), despite studies increasingly indicating the home as the preferred place (Gomes et al. 2013, Rainsford et al. 2016).

The common essential features of the modern ‘good death’ are thought to include being pain free, maintaining dignity, support of family, autonomy in decision-making for the dying person and opportunity to ‘sort out personal affairs’ (Raisio et al. 2015, Davies et al. 2016, Meier et al. 2016). However, different stakeholders have different priorities and expectations of end-of-life care (EoLC) (Holdsworth 2015, Davies et al. 2016, Meier et al. 2016). Ideally, it must reflect the needs of the community and in particular those of the dying person and their carers (Cottrell & Duggleby 2016). One voice that remains largely unheard is that of rural palliative care patients and their families (Bakitas et al. 2015).

One challenge in finding the rural voice is the difficulty in establishing consensus on a ‘rural’ definition. While efforts are made to define ‘rural’ geographically (based on population density or distance from services), Wilson et al. (2009a,b) suggest rural people define themselves as ‘rural’ and perceive themselves as different from urbanites. Studying rural views of the ‘good death’ is important because these may differ from urban views (Spice et al. 2012). In addition, ageing is more pronounced in rural areas, and rural areas typically have fewer health and social services as compared to urban areas (Downing & Jack 2012). For example, the growth in Australia's population aged 65 years or older is expected to rise by 139% between 2000 and 2030, with a 180% increase anticipated in rural areas (Australian Report 2008).

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify and chart current research knowledge on the ‘good’ rural death through the perspectives of rural residents, including rural patients with a life-limiting illness, rural family members/informal caregivers (FCG), rural healthcare providers (HCP) and the wider rural community; and to identify gaps in the literature for areas for future studies to better understand the concept of ‘good death’ for rural people. This review will add to an understanding of the rural perspective on the ‘good death’ to guide researchers, healthcare professionals and policy makers in future planning and development of rural EoLC.

Methods

Protocol

Currently, there is no standardised definition or methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al. 2015); however, the definition commonly applied is that used by Arksey and O'Malley (2005). The protocol used in this review is based on the methodological framework first described by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), enhanced by Levac et al. (2010), Colquhoun et al. (2014) and Daudt et al. (2013) and later refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI 2015). The original (Arksey & O'Malley 2005) and modified (Levac et al. 2010) frameworks consist of six stages (JBI, 2015).

Despite scoping reviews becoming increasingly popular (Tricco et al. 2016), there are no standardised reporting guidelines. Tricco et al. (2016) identified the need for guidelines to ensure scoping reviews are validate and reliable. The reporting of this review is based on the 2016 scoping review published by Tricco et al. (2016), the team that is developing the standardised reporting guidelines, as well as the PRISMA-Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Equator Network, 2016). While quality assessment is not a requirement of the JBI guidelines, it will be included in this review (Levac et al. 2010, Daudt et al. 2013).

Eligibility criteria

Scoping reviews have a broad approach and include any existing literature regardless of study design, discipline or quality. In order to answer the research question ‘How do rural residents describe the “good death” concept within a rural setting?’ eligibility criteria were developed to clearly identify the purpose of the review and guide the reviewers in deciding which articles to include.

The eligibility criteria were developed using the JBI (2015) guidelines using the Participants, Concept and Context acronym.

- Participants: Rural residents including rural patients with a life-limiting illness, rural FCGs, rural HCPs and the wider rural community as these are the most appropriate to provide the rural perspective. No age filter was applied.

- Concept: The principal concept under review was the ‘good death’ in a rural setting as described through the personal experiences or perspectives of rural residents; collected by interviews, surveys or extensive field work observations. The term ‘good death’ was either used explicitly or implied.

- Context: Rural or remote; all countries and territories were considered; no standardised definition of rurality was used. Articles that included urban and rural data were considered providing the rural data were clearly identifiable.

Information sources and search strategy

The principal researcher conducted the comprehensive literature search. Five electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO and Web of Science) were searched from 2 January to 14 February 2016. The following keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were used in the final search: (“good death” OR “managed death” OR “good enough death” OR “tamed death” OR “dying well” OR “peaceful death”) AND (Rural OR Remote). This iterative process had ‘peaceful death’ omitted from the original search. All study designs were included; no date filter was applied; only English language papers were included.

The initial searches identified 377 articles. These were downloaded to ENDNOTE X7, merged and duplicates were deleted (338 articles). The reference lists of all retained articles were scanned for additional studies. The principal author also hand-searched recent issues (July 2014–Jan 2016) of eight relevant journals (Palliative Medicine, Journal of Palliative Medicine, Palliative and Supportive Care, Australian Journal of Rural Health, Journal of Rural Health, Social Science and Medicine, Health and Place, Death and Dying) for additional articles. The Cochrane Library, CareSearch database and OpenGrey repository were searched for grey research literature. The authors of three studies reporting mixed rural/urban geographical data were contacted; however, rural data were confirmed as not specified, and so these three articles were excluded from this review.

Study selection process

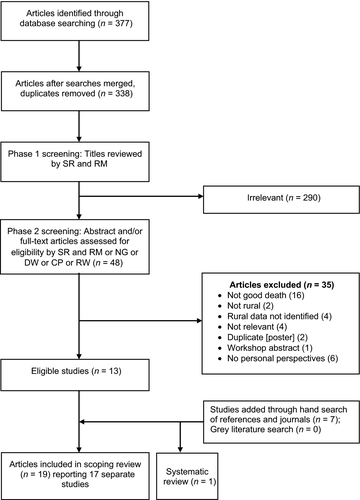

Phase 1 screening (review of titles) was carried out independently by two authors. At least two authors independently screened the abstracts and/or full text of potential articles (see Figure 1 for flow chart). Rejected articles were either clearly irrelevant or those that addressed the topic in general but failed in one or more of the inclusion criteria. Due to geographical distances, differences were discussed via email and resolved by consensus.

Flow diagram of scoping review selection process including reasons for exclusion.

Source: Modified flow chart as described by Moher et al. (2009).

Data extraction and charting

Data from each accepted article were extracted by the principal author and entered into a table according to predefined headings (JBI, 2015). Three co-authors independently read the retained articles and added their comments to the table indicating agreement/disagreement/additions/deletions. Differences were discussed via email. The final version was emailed to all co-authors for verification.

Assessment of quality

The current scoping review methodological guidelines do not require a formal quality assessment of eligible articles to ensure valuable insights reported in lower quality studies are not excluded. However, a quality assessment was conducted in this review to assist in validating the quality of the literature. All eligible articles are retained in this scoping review regardless of their quality.

The quality of each study was assessed independently by four co-authors. Some high-quality studies received a lower score as the assessment was based on aspects relevant to the rural ‘good death’ and not of the study per se. All studies were rated to be of low, medium or high quality based on a simple scoring system described by Gomes et al. (2013) and modified to account for the rural ‘good death’ focus. Two additional items were included: (1) clarity of rural definition and (2) validity of informant (prospective = 2, retrospective = 1, well community = 0).

Synthesis

The synthesis included both a quantitative analysis of the actual scoping review and a qualitative analysis of the content of the included articles. Both analyses were conducted by the principal author and verified by one of three co-authors. The quantitative analysis is charted and described in frequencies. A thematic analysis of the qualitative content was conducted by downloading the eligible articles into NVivo-10, coding for major themes and reported narratively. Due to heterogeneity within a small number of studies, a meta-analysis and analysis according to informants were not possible. Some informant groups had only one study identified.

Results

Literature search

A total of 377 potential articles were identified from the electronic searches. After merging the searches and removing duplicates, 338 manuscripts were identified and 13 remained after two screening phases (see Figure 1). Hand-searches of journals and reference lists identified an additional seven articles. Consequently, 20 articles reporting on 17 studies and one systematic review were included in this scoping review (see Table 1).

| Purpose | Informants | Rural definition | Methodology | Good death description | Findings in relation to good death | Quality/Limitations/Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arnaert et al. (2009) Western Quebec (Canada) Rural N = 5 |

To explore home-care nurses' attitudes towards palliative care (PC) in a rural community. Palliative care journal |

5 home-care nurses; all residents of the rural community. |

Vast, sparsely populated area geographically isolated with few health or social services. Rural study |

Qualitative face-to-face semi-structured ITVs and FGD; thematic analysis. | ‘If they [the patients] die with dignity and they are conscious right to the end, and they haven't suffered, then … they have had a good death’ [nurse]. | Six themes identified:

|

Medium Small sample size; employed by PC service. |

|

Beckstrand et al. (2012, 2015) Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Alaska (USA) Rural N = 236 |

To discover size, frequency, and magnitude of obstacles in providing end-of-life care (EoLC) in rural emergency departments (ED). Emergency nursing journal |

52/73 rural hospitals agreed to participate; 236/508 surveys returned by registered nurses. |

Small rural communities with critical access hospitals (CAH). Rural study. |

Cross-sectional survey design; 57-item survey included 15 demographic, 3 open ended and 39 Likert questions. | To be comfortable and free of pain, the family is able to perform EoL rituals, others are respectful of the patient's dignity, and families have adequate time to say goodbye. |

GD = ideal death Obstacles to ideal death in rural ED includes personally knowing the patient or family; lack of privacy for the dying patient due to poor design; issues with family members; unknown patient wishes; nurse/physician power struggle; Phone calls from family, etc. detract from time with patient. |

Medium Convenience sample; ED nurses; focus mainly sudden or accidental deaths within the ED. |

|

Biggs (2014)Canada Rural N = 19 |

To explore how dying persons and their caregivers experience spiritual care in their homes as an aid to dying well and having a GD. To examine effect of rural geography on the experience. Doctoral thesis |

10 dying persons and 9 caregivers. |

Grey and Bruce Counties described as rural comprising towns of various sizes and farms (no specific details). Rural study. |

Phenomenological study and interpretive analysis; semi-structured ITVs. | With spiritual care ‘people's needs are fulfilled, their suffering is lessened and there is an increased possibility of them experiencing a good death’. |

EoL spiritual care facilitates ‘GD’ by helping dying persons and their FCG to experience connection and support to people and traditions they consider necessary to die well; provides personal inner resources including hope, comfort, self-worth, strength to cope, and peace of mind. Rural residency contributed positively to their experience of a GD. |

High Small sample size limitation is counterbalanced by depth of interviews. |

|

Cruickshank et al. (2010) Scotland Rural N = 24 |

To understand the impact on patient care by use of syringe drivers (SD) in rural communities Palliative care journal |

4 terminal patients, 8 informal carers, 12 community nurses. |

‘Typical Scottish rural community’. Town 15,000 and surrounding rural area. Rural study. |

Phenomenological approach; Patient ITVs at home; carer bereavement ITVs; 2 community nurse FGDs. | Good pain relief makes a GD; however, many other issues to consider ‘it [syringe driver] helps the pain but that's all it helps’ [patient]. |

Factors influencing good death:

EoLC is complex; Community nurse is central to EoLC; Rural challenges include distances and limited staff. |

Medium Patients enrolled in palliative care service; had SD at recruitment; biased towards symptom control. Not focused on GD; focused on determining EoLC needs in a rural community |

|

Counts and Counts (2004) West New Britain (Papua New Guinea) Rural N = whole community |

‘The good, the bad, and the unresolved death in Kaliai’ Social science and medicine journal |

Authors' observations and interviews with residents. |

Isolated NW island; 1000 Melanesian Lusi-Kaliai residents; accessible only by sea. Government clinic operated at Roman Catholic Mission. Rural study. |

Qualitative Long-term Anthropological field work (1966–1967, 1975–1976, 1981, 1985). Case studies |

‘A good death is under the control of the dying person and is the result of the natural process of ageing’. [author]; ‘death is either good or bad depending on whether it is the consequence of bad social relationships and causes social upheaval’. |

GD = ‘peaceful death’; 5 elements: social (at peace with others, mutually); psychological or spiritual (at peace with one's own life and death and ‘soul’); timing (natural death/old age); spatial (at home, surrounded by relatives A GD rarely happens; it is a controlled, quiet death of elderly as result of the natural process of ageing. Bad death implies a rupture of social relations and results in the destruction of peace and social order. Combination of traditional and Christian beliefs. Social death versus physical death |

Low Observation – researcher bias however data collected over many years. Understanding of good and bad death is very much based on localised cultural constructions and may not necessarily reflect general beliefs and customs. Old study – findings may no longer be relevant. |

|

Devik et al. (2013) Rural N = 5 Norway |

To explore and understand lived experience of older cancer patients living alone. Oncology nursing journal |

5 older patients with incurable cancer; >70 years; living on their own. |

Communities with low-population density; population 920 to 7775. Rural study. |

Qualitative; phenomenological hermeneutical approach; narrative interviews. | ‘Good death’ is implied; could be inferred to be a noble death; acceptance comes through maintaining a will to live; the hope to stay alive is not death-renouncing, but rather life-affirming. |

Importance of maintaining dignity, identity and value; enduring by keeping hope alive by continuing chemotherapy as a means of delaying death and retaining a positive outlook; maintaining autonomy by mobilising personal resources; not to become a burden on family, friends and services. Challenges: coping with conflicting feelings of hope and despair; navigating alone as patient and self-care provider; living up to expectations of being a good patient; limited control; risk of losing one's identity and value; loss of former life; services not always available in rural areas therefore need to be self-reliant. |

Medium Small sample; recruitment bias (polyclinic); patients undergoing chemotherapy; patients living alone. |

|

Dilger (2008) Tanzania |

To explore how moral perceptions of HIV/AIDS-related illness and death in rural Tanzania are related to social and cultural practices of disease interpretation, patient caring and burial. Anthropology Journal |

Young men and women with HIV/AIDS (minor ethnic group.) |

Mara Region in Tanzania; rural; borders on Lake Victoria in the west and Kenya in the north; farming and fishing. Rural study. |

Anthropological field work; Research 1999–2000. | A controlled, quiet death of elderly as result of the natural process of ageing. | ‘Bad death’ – physical and spiritual with social, cultural and moral components. Suicide is an example of a bad death → negation and rejection of social order; HIV/AIDS is a ‘bad disease’ inferring a ‘bad death’- painful for individuals and their families; premature death breaks continuity of whole families and lineages as young people die without leaving children from ‘legitimate relationships’; disturbs social equilibrium and kinship networks; considered a ‘final death’ as prevents fulfilling of ritual requirements. |

Low Field work and case studies with no reporting of methodology; no reflexivity; Results possibly not generalisable due to small ethnic group with specific cultural practices and young age of informants.. |

|

Easom et al.(2006) USA Rural N = 9 |

Pilot study to evaluate effects of an education intervention on EoLC knowledge and perceptions in GD definition. Palliative care journal |

Convenience sample; 9 rural nurses working in assisted living and nursing home environments |

Rural = access; distance >75 miles from large metropolitan area. Rural study. |

Mixed study; written questionnaire. In regard GD attitudes: Qualitative: 2 open-ended questions. Q1: ‘What is your belief regarding what constitutes a “good death”?’ Q2: ‘What impact do cultural values have on death and dying?’ |

To die painlessly, comfortably and hopefully in one's sleep. |

Attitudes and perceptions of participants changed in defining what constitutes a ‘good death’. Q1: Pre-education: to die painlessly, comfortably, and, hopefully in sleep. Post-education: adding importance of family involvement; Respect and compliance with patient and family wishes. Q2: No change in knowledge and attitudes relating to significance of cultural values on the process of death and dying.

|

Low Small convenience sample; Recruitment bias. Pilot study. Not focused on GD- evaluated staff EoLC education programme. |

|

Felt et al. (2000) Kansas, USA Rural N = approx. 50 |

To address under-utilisation of rural hospice services; To determine attitudes, values, beliefs and practices surrounding EoLC. Palliative care journal |

Targeted communities; purposive selection of active community leaders. |

Six rural communities in Kansas. Rural study. |

Qualitative; 6 FGDs of 7 to 10 people; discussions recorded, transcribed, reviewed individually; comparisons made between groups → themes identified. | Best scenario for one's own death ‘in my sleep’ or ‘hope it happens quick’; at home or ‘someplace comfortable, quiet, and peaceful, with family’ and loved ones nearby; to ‘make peace’, to ‘forgive and forget’, to be honest about what was really happening; permission to die from loved ones very important to a peaceful death. |

GD = ‘best scenario for own death’ Important themes:

Some wanted to die alone after closure with loved ones. |

Medium Selection bias; minority groups not represented; script-guided discussion. Focused on determining EoLC needs in a rural community rather than GD. |

|

Grant et al. (2003) Rural Kenya, sub-Saharan Africa Rural N = 56 |

To describe the experiences and needs of dying hospital patients and their FCG to determine what constitutes a GD in sub-Saharan Africa. Palliative care journal |

32 adult patients (cancer or AIDS); 24 carers; mostly Christian however traditional beliefs still strong; identified by hospital doctor; stratified by home and hospital care. |

Eastern slopes of Mt Kenya (Meru District). Population density 363/km2 to 65/km2- poverty, drought, poor infrastructure. Population mostly Christian. Rural study. |

Qualitative; Semi-structured ITVs; not recorded, hand written notes + impressions and observations; transcultural researcher; multidisciplinary advisory group; multiple data sources; ITVs completion once saturation achieved; constant comparison; thematic analysis. | Dying with dignity or dying well is outside the grasp of most due to overwhelming pain, poverty, sense of burden, guilt, and need for basics of life. |

Positive: support of close family relationships, care shown by community and religious fellowships helped meet many of their emotional, social, and spiritual needs; accepted by relatives. Negative: physical needs were often unmet. Unresolved suffering- pain, poverty, guilt of using all available family resources to pay for treatment and care. Needs: accessible pain relief, affordable clinic or inpatient care, help to cope with the burden of care. Holistic approach to the GD. |

High Limited generalisability to sub-Saharan Africa. Selection bias- recruited from hospital. Small sample, single ethnic group; Interviews not recorded, however, rigour in recall; cancer/AIDS focus. |

|

Grant et al. (2011) Uganda, Kenya and Malawi Rural N = 162 |

To describe patient, family and local community perspectives on the impact of three community based PC interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. Palliative care journal |

33 patients with advanced illness, 27 family carers, 36 staff, 25 volunteers, 29 community leaders and observed clinical care of 12 patients. |

Uganda: mobile PC service 120 km from Kampala; includes fishing communities on Lake Victoria. Kenya: rural, 240 km from Nairobi. Malawi: peri-urban districts of Blantyre. Influence of Christian missionaries. Rural study. |

Rapid assessment evaluation; Qualitative; photographic ethnography; rapid evaluation field studies; ITVs with key informants; direct observations of clinical encounters; review of local PC information; data triangulation; thematic analysis. |

‘To let people die in peace’; ‘now patients die with dignity’ with a ‘sense of hope’. Good death implied |

Good death facilitated by: Patients and family carers: Pain control; being treated with dignity and respect; being supported at home reduces physical, emotional and financial burden of travel; practical support; rapid access to clinical and social support networks. GD requires a holistic approach especially good pain management. |

Medium Service evaluation; selection bias; small samples. Palliative care present → may inhibit honest responses. |

|

Gysels et al. (2011) Sub-Saharan Africa |

To synthesise qualitative research on EoL to inform policy, practice and further research. Palliative care journal |

– | Studies relating to the GD were conducted in rural Ghana, Tanzania, and Kenya. | Systematic review |

Ghana: Bad death is a death that come too early, or believed to be punishment for sins. Tanzania, Kenya: bad death related to ‘bad disease’ (HIV/AIDs). |

GD versus bad death and stigma. Cultural beliefs impact EoLC for patient, family and community. Ghana: elderly, death welcomed, brings peace and rest. Bad deaths –early, punishment for sin. A good funeral was part of a good death. Tanzania: studies related to stigma attached to HIV/AIDs, associated with immoral behaviour = bad death. Kenya and Tanzania: HIV/AIDs death denied status of ancestors → threatened continuity of clan and community; buried outside the homeland → loss of dignity and complicated bereavement. |

Systematic review; methodologically sound not GD focused. Systematic review based on EoLC in sub-Saharan Africa; predominantly HIV/AIDS among young people; Findings not generalisable outside this cohort. |

|

Huy et al. (2007) Vietnam Rural N = approx. 80. |

To explore sociocultural + health system factors impacting registering of deaths by lay people. World health and population journal |

Purposive selection; Farmers, lived in hamlet >5 years. |

Commune 6000–10,000; each divided into a number of small hamlets. Vietnamese folk religion and Christianity. Rural study |

Qualitative 9 FGDs (6–11 participants); audio recorded and transcribed; translated in to English; thematic analysis | GD is an ‘honourable death’ |

Types of death:

Bad and infant deaths more likely to be unreported due to family stigma and babies not recognised as a ‘person’ |

Low FGDs possibly not appropriate in this culture and may inhibit discussion; not generalisable; no reporting of researcher bias or reflexivity; no indication of participants' personal experience with dying (implied). |

|

Joarder et al. (2014) Bangladesh Rural N = 8 |

To explore perceptions of the meaning of death among elderly people in a Bangladeshi community, and to understand how the meaning of death affects one's overall well-being. Cross-cultural gerontology journal |

5 male +3 female elderly villagers. Data collected 2008. |

Rural village (Kakabo), Savar sub-district 25 km from Dhaka. Mostly Muslim; few Hindu and Christian. Rural study. |

Qualitative; purposive sampling; in-depth ITVs; daily routines; informal discussions; Participatory Rapid appraisal tool box. Coding and categorising patterns. | Peacefully, without suffering, surrounded by family |

Physical versus spiritual death; duality of body and soul. ‘Good death’ – peacefully, without suffering, surrounded by family. This manner of death was given by God; the result of good actions in life. ‘Bad death’ = caused by hanging, poisoning, homicide, and accidents; earned through bad deed; bad ‘karma’. |

Medium Short time interval (3 days); age difference between interviewers and participants (respondents considered interviewers too naïve to discuss serious issues); beliefs based on local cultural traditions with religious influences limiting generalisability. |

|

Knight (2014) England Rural N = 4 |

To explore the views of clergy about the constituent elements of a ‘good death’. |

4 Church of England clergy working in rural or town parishes. (10 clergy including 3 rural, 1 town, 2 suburban; 4 not specified) |

Diocese of Worcester. Urban/Rural study; rural data identified. |

Qualitative; random sample; structured ITVs using flash cards; thematic analysis and scoring of cards. | Different meanings of ‘Good Death’ depending on perspectives, cultures; individual concept. |

Spiritual care slightly more significant than emotional care and more important than physical care. Social domain lowest priority. Spiritual care: ‘to be at peace with God’;‘to say goodbye to important people in my life’ Emotional care: ‘dignity; sense of humour’ Physical care: pain free; ‘To have human touch’. Social care: to have my family with me'

|

Medium Small sample size; clergy bias; single researcher. |

|

van der Geest (2004) Ghana Rural N = 35 |

An essay considering ‘good death’ and ‘bad death’ in rural Ghana. Social science and medicine journal. |

Residents, mostly farmers, of Kwahu-Tafo, southern Ghana. |

A rural town; population 6000; farmers and traders. Christian, mostly Roman Catholic. Rural study. |

Anthropological fieldwork carried out intermittently from 1994 to 2004. Interviews, participant observations, school questionnaires, FGD. | A good and peaceful death comes ‘naturally’ after a long and well spent life. |

‘Good death’ = a peaceful death: having finished all business, made peace with others; being at peace with own death; not by violence, accident, fearsome disease, without much pain; at home, surrounded by children and grandchildren; a death accepted by the relatives. 5 aspects: social, psychological, spiritual, timing, spatial. However, ‘good death’ is ambiguous as quality is open to interpretation by all stakeholders. |

Medium Not a study with methods but extensive field work, open to researcher bias. No reflexivity provided; not generalisable; ethics not described. |

|

Viellette et al. (2010) Quebec, Canada Rural N = 36 (concerning 70 cases) |

To obtain perspectives on what constitutes a good death from persons living in French speaking rural Quebec. Palliative care journal |

ITV: 25 long-term rural community members with personal or professional experience of death and dying. FGD: 11 healthcare providers, community services and EoL policy makers/administrators. |

Region A: considerable distance from Quebec city. Region B: close to Quebec City. Rural study. |

Qualitative ethnography; validation of themes previously identified (Wilson); 25 ITVs; 2 FGD(5 + 6); audio taped; transcribed; coding; themes; iterative; saturation. | ‘Enjoying a good quality of life while dying (and their family) was essential to a good death’. |

GD: four dimensions – physical, spiritual, social and emotional–psychological. Essential elements:

Rural Specific: to die in one's own community, reliance on neighbour support. Some would prefer to have less care and fewer services than be removed from community (family and friends). Gaps in available services are limiting factors to a GD. |

High Study in 2 small areas of a large province; retrospective views- some of many years; no First Nations; few males; recruitment bias: self-selection. |

|

Alberta, Canada Rural N = 34 |

To gain a conceptual understanding of the ‘good death’ in English speaking rural Alberta. Palliative care journal |

ITVs: 13 community members with personal or professional experience of death and dying; self-selection. FGD: 21 healthcare providers and policy makers. |

Region A: Metro-adjacent; Region B: Non-metro-adjacent. Rural study. |

Qualitative ethnography; Document review; site observations; interviews (13); themes validated by 2 focus groups (9 + 12); audio tapes transcribed; coding; themes; iterative; saturation. | The good rural death is contextualised. Dying outside one's rural community is considered a 'bad death |

Four themes:

Rural people have less access to specialist palliative care. |

High Limitations not noted however researcher reflexivity and bias is acknowledged; selection bias; small sample. |

- Findings reported are in relation to good death and do not necessarily reflect full findings of the study.

- ABBREVIATIONS: PC palliative care; ITV interviews; FGD focus group discussion; QoL quality of life; GD good death; EoLC end-of-life care.

Study characteristics

The included articles were published 2000 through 2015 (see Table 2), with data collected between 1981 and 2013. Rural perspectives were reported in articles from both developed and developing countries – Canada (5), USA (4), Kenya (2), United Kingdom (2) and one each from Norway, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea, Uganda, Malawi, Ghana and Tanzania. One study (Grant et al. 2011) and the systematic review (Gysels et al. 2011) collected data from more than one country in sub-Saharan Africa. One Canadian manuscript (Wilson et al. 2009b) compared data collected from two studies (Wilson et al. 2009a, Viellette et al. 2010) conducted in different Canadian provinces using the same study protocol. With the exception of two articles (Gysels et al. 2011, Knight 2014), all studies were described as rural; no remote communities were specified. No standardised definition of rurality was reported. The research quality assessment is reported in Table 1.

| Developed (n = 10) | Developing (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Date of publication | ||

| 2000–2004 | 1 | 3 |

| 2005–2009 | 3 | 2 |

| 2010–2015 | 6 | 3 |

| Countries | ||

| Developed (n = 10) | ||

| North America | 7 | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 2 | 0 |

| Norway | 1 | 0 |

| Developing (n = 7) | ||

| Africa | 0 | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 0 | 1 |

| Vietnam | 0 | 1 |

| Papua New Guinea | 0 | 1 |

| Source of article | ||

| Journal | 9 | 8 |

| Dissertation | 1 | 0 |

| Source discipline | ||

| Palliative/hospice care | 7 | 3 |

| Social Science and Medicine | 0 | 2 |

| Other nursing | 2 | 0 |

| Population health | 0 | 1 |

| Anthropology | 0 | 1 |

| Cross-cultural gerontology | 0 | 1 |

| Theology | 1 | 0 |

| Study objective included ‘Good death’ | 4 | 3 |

| Type of article | ||

| Qualitative (n = 17) | ||

| Phenomenological | 3 | 0 |

| Ethnographic | 2 | 1 |

| Open ended written survey | 2 | 0 |

| Anthropological field work | 0 | 3 |

| Not specified | 3 | 3 |

| Systematic review | 0 | 1 |

| Methodsa | ||

| Interviews | 7 | 4 |

| Focus groups | 5 | 3 |

| Observations/field work | 0 | 4 |

| Written surveys | 2 | 0 |

| Clinical observations | 0 | 3 |

| Terminology | ||

| Good death | 7 | 4 |

| Peaceful | 0 | 2 |

| Other | 3 | 1 |

| Bad death | 0 | 1 |

- a Some studies used more than one method.

Objectives of the included articles

To explore or describe the ‘good death’ concept through the perspectives of rural residents was the objective of seven studies (Grant et al. 2003, Counts & Counts 2004, van der Geest 2004, Wilson et al. 2009a,b, Viellette et al. 2010, Knight 2014, Biggs 2014). Seven studies (Felt et al. 2000, Arnaert et al. 2009, Grant et al. 2011, Gysels et al. 2011, Beckstrand et al. 2012, 2015, Devik et al. 2013, Joarder et al. 2014) implied the ‘good death’ by focusing on quality EoLC. The ‘good death’ was not the primary objective in the remaining three studies (Easom et al. 2006, Huy et al. 2007, Cruickshank et al. 2010) but was a point of comment by rural participants noted within the article text.

Methods of data collection

All eligible studies were qualitative in nature. Twenty-nine focus groups and 378 interviews were conducted; 245 written surveys were completed; eight clinical encounters were detailed and six communities were observed. Sample sizes ranged from four (Knight 2014) to whole communities (Counts & Counts 2004, van der Geest 2004, Easom et al. 2006, Joarder et al. 2014). With the exception of one urban–rural study (Knight 2014), all the included studies were classified as being solely rural in focus.

Participants

The exact number of participants is unknown as two anthropological fieldwork studies included whole communities (Counts & Counts 2004, Easom et al. 2006). Of the 751 identified rural participants, 84 were rural patients, 68 rural FCGs, 323 rural HCPs, 153 rural residents, 83 rural community leaders and 40 rural health administrators and policy makers. Of the identified informants, 20% were patients or FCGs and of these 76% were African. HIV/AIDS (considered a stigmatised disease) or cancer accounted for most terminal illnesses in Africa. All participants were adults and when reported, their ages ranged from 18 to 94 years. Participants over 80 years of age were interviewed in Canada (Biggs 2014), Bangladesh (Joarder et al. 2014) and Kenya (Grant et al. 2003). Of the 19 patients in developed nations, 17 had cancer, one dementia and one cerebral vascular disease.

Concept

All the eligible articles reported on the ‘good death’ from the perspectives or experiences of rural residents. The term ‘good death’ was used explicitly in eight titles (PNG [1], Africa [2], Britain [1], Canada [4]) and an additional six abstracts (USA [2], Africa [2], Bangladesh [1], Vietnam [1]). For those studies not using the exact term, all implied the ‘good death’ within the report or used an alternative term such as the ‘ideal’ death (Beckstrand et al. 2012, 2015), ‘the best scenario for one's own death’ (Felt et al. 2000), an ‘honourable death’ (Huy et al. 2007), ‘dying with dignity’ (Grant et al. 2011), ‘dying peacefully’ (van der Geest 2004, Grant et al. 2011), dying ‘the proper way’ (van der Geest 2004) and ‘facing death in a brave manner’ (Devik et al. 2013). One study focused on the ‘bad death’ (Joarder et al. 2014). The ‘good death’ referred to the death event, the dying process, the meaning of death and the after-death concept.

The dominant theme, from both developed and developing countries was that a ‘good death’ is one that is peaceful, that is free of pain and without suffering. Other themes describing the ‘good death’ included a ‘controlled’ death (control over symptoms, place of death, decision-making, manner of death and to remain independent) (Felt et al. 2000, Counts & Counts 2004, Dilger 2008, Wilson et al. 2009a,b, Viellette et al. 2010, Knight 2014); a ‘timely’ death (Counts & Counts 2004) that is a death coming ‘naturally and after a long and well-spent life’ (van der Geest 2004, p. 899) and ‘hopefully in my sleep’ (Felt et al. 2000, p. 405) after having had opportunity to say goodbye to family; a ‘dignified’ death by maintaining identity, self-worth, integrity and control (Wilson et al. 2009a, Devik et al. 2013); a ‘social’ death such as to die within the community with family present (Wilson et al. 2009a,b) and a ‘noble’ death such as through enduring the situation (Grant et al. 2003, Devik et al. 2013). Two articles (van der Geest 2004, Knight 2014) acknowledged the difficulty of defining a ‘good death’ as it is dependent on individual interpretations, perspectives and priorities.

Despite the challenges of definition, the review team determined that rural residents identified five dimensions they considered important for facilitating a ‘good death’ – physical, emotional, social, spiritual and cultural dimensions.

Physical (pain and symptom management)

Good pain and symptom control was the overriding factor reported to ensure a ‘good death’. Pain relief was central to maintaining quality of life through the dying journey, not only just for the patient but also the FCG (Cruickshank et al. 2010).

In both developed and developing communities, physical care also includes human touch (Grant et al. 2011, Biggs 2014), ‘touching [wounds] helps put a smile on people's faces’ (Ugandan nurse; Grant et al. 2011, p. 10). In contrast, western participants ‘fear a technological death as opposed to a good death’ (Felt et al. 2000, p. 401), while in Ghana, ‘death was peaceful and no medical battle was fought to keep him alive’ (van der Geest 2004, p. 902).

While acknowledging the importance of symptom control, participants in two studies (Cruickshank et al. 2010, Grant et al. 2011) highlighted the need for a holistic approach to the ‘good death’ including ‘emotional, spiritual, social and practical care’ (Grant et al. 2011, p. 1).

Emotional

Living well while dying (Viellette et al. 2010, Devik et al. 2013) and maintaining dignity, respect, self-worth, autonomy and possibly also a sense of humour were all reported as essential for facilitating a ‘good death’. In order to maintain autonomy, ‘the dying person needed to be lucid, to be able to think, and to have enough energy and mental alertness to share their thoughts and feelings’ (Wilson et al. 2009b, p. 315). The distress of not respecting patients' wishes was voiced by a number of rural emergency room nurses who indicated that ‘one obstacle to providing [quality] EoLC is not knowing the patient's wishes regarding the continuation of treatments or tests because of [their] inability to communicate’ (Beckstrand et al. 2012, p. 16). Research participants from both developed and developing countries felt it was important to know the truth about their illness (Felt et al. 2000) so they could be ‘at peace with their own death’ (van der Geest 2004, p. 908), ‘stop chasing [expensive] false hopes’ (Grant et al. 2003, p. 161) and prepare for death; however, not all families want the patient to know the truth (Grant et al. 2003). Fear and anxiety were cited as impediments to peace (Devik et al. 2013).

Social

Most rural participants identified the importance of family and community. While a minority wanted to ‘die alone, but only after having had closure with loved ones so that death would be peaceful’ (Felt et al. 2000, p. 405), most rural residents in all regions and cultures said it was important to have family and significant people present because ‘the togetherness of the family members makes you feel they love you and are not abandoning you’ (Grant et al. 2003, p. 163). African participants talked of the important role that family and community plays after death in ensuring specific rituals are carried out. Acceptance of the death by family members and ‘permission to die from loved ones [is] very important to a peaceful death’ (Felt et al. 2000, p. 405).

Before one dies conflicts should be ended and enemies reconciled, debts should be paid and promises fulfilled. Someone who has been able to achieve this, is ready for his final departure. He is … a peacemaker, a person who is respected by others. (van der Geest 2004, p. 908)

The place of death has significance with most rural informants wishing to die ‘at home, which is the epitome of peacefulness, surrounded by children and grandchildren’ (van der Geest 2004, p. 899) as ‘the home or home community … [is] the only place where the dying person [can] be close to the many people who have meaning for them’ (Wilson et al. 2009b, p. 316). In Ghana, dying away from home is considered ‘bad’ and disgraceful; however, partial restoration can be achieved by ‘bringing the dead body home’ (van der Geest 2004, p. 909). Some participants considered these social elements a low priority and thus relatively unimportant (Knight 2014).

Spiritual

One of the most important spiritual elements was the acceptance of death … that could be reached through a process of dying well. For this state to occur, the dying person needed to find meaning in their life and also meaning in their daily experience. (Wilson et al. 2009b, p. 315)

Cultural

The influence of cultural beliefs and values was evident in most articles with rural Kenyan participants illustrating how ‘powerful cultural traditions [make] it difficult for social needs to be met’ (Grant et al. 2003, p. 163). Religion was found to be a component of cultural beliefs and values, with Christian religions most commonly identified (Grant et al. 2003, 2011, Counts & Counts 2004, van der Geest 2004, Knight 2014, Biggs 2014). However, in some developing countries, while Christianity has ‘greatly influenced’ (van der Geest 2004) the concept of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ death, it has not replaced, but instead has been interpreted and applied to traditional beliefs (Grant et al. 2003, 2011, Counts & Counts 2004, van der Geest 2004, Huy et al. 2007). In Vietnam (Huy et al. 2007), Papua New Guinea (Counts & Counts 2004), Bangladesh (Joarder et al. 2014) and Ghana (van der Geest 2004), the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ death concepts were aligned with the circumstances surrounding the death and afterlife, as these significantly impact on the health and well-being of the community, descendants and ancestors. The ‘good death’ is also one that does not disrupt the life and health of the community (van der Geest 2004). Rural residents in developed countries instead viewed the ‘good death’ in the light of a bio-medical model, placing greater emphasis on autonomy, the process of dying and minimising any sense of struggle. The afterlife provides the dying person with a ‘hope of something more to come’ (Biggs 2014). The culture of ‘not complaining’ was reported in both developed (Devik et al. 2013) and developing countries (Grant et al. 2003). ‘Poverty shaped how people died’ (Grant et al. 2011, p. 5) in rural sub-Saharan Africa.

Context

The overriding theme is that rural residents prefer to die at home, and when this is not possible then in their rural community (Wilson et al. 2009a,b, Viellette et al. 2010, Biggs 2014). ‘Some would prefer to have less care and fewer services’ (Viellette et al. 2010, p. 163) than leave their community.

Wilson et al. (2009a,b) reported that rural residents recognised unique challenges of providing EoLC in rural areas. These include distance (Grant et al. 2003, 2011, Wilson et al. 2009a,b, Cruickshank et al. 2010), lack of services and personnel (Wilson et al. 2009a,b, Viellette et al. 2010, Devik et al. 2013), emotional and physical isolation for independent HCPs (Arnaert et al. 2009), lack of access to specialist palliative care (Wilson et al. 2009a,b) and the distress of caring for close friends and colleagues (Arnaert et al. 2009, Beckstrand et al. 2012, 2015). It was obvious there are many advantages as well, such as the deep concern of community for its members (Wilson et al. 2009a,b). The benefits include personal attention (Arnaert et al. 2009, Wilson et al. 2009a,b, Beckstrand et al. 2012, 2015, Biggs 2014) and ‘the friendliness and closer-knit nature of a rural setting … the increased level of concern persons have for one another, and the resources available’ (Biggs 2014, p. 139). The rural environment was ‘identified as a much quieter and contemplative setting’; however, ‘dying outside the rural community is a common and highly problematic issue for rural people’ (Wilson et al. 2009b, p. 317).

Discussion

Principal findings

This scoping review identified 20 articles describing the concept of the ‘good’ rural death from the perspectives of a cross-section of rural residents including rural patients with a life-limiting illness, rural family members/informal caregivers, rural HCP and the wider rural community; and identified gaps in the literature for areas for future studies to better understand the concept of ‘good death’ for rural people. Both developed and developing countries were represented, with most data coming from North America and sub-Saharan Africa.

Despite the challenges of rural definition, and notwithstanding differences in rural locations, cultural perspectives, priorities and expectations, this scoping review found similarities and differences in perspectives with those reported in urban studies. The four elements (physical, spiritual, emotional and social) considered essential by the WHO (2015) to facilitate a ‘good death’ were identified as pain/symptom control, dignity, preparedness, autonomy and community and are consistent with urban findings (Holdsworth 2015, Raisio et al. 2015, Davies et al. 2016, Meier et al. 2016). However, the context and priority placed on each factor differed between included studies and from urban perspectives (Kirby et al. 2016).

While death is a normal end to life (WHO 2015), one could argue that many deaths are not entirely ‘good’ due to the nature of the illness (Holdsworth 2015), the age of the dying person (Counts & Counts 2004, van der Geest 2004, Huy et al. 2007, Dilger 2008) and individual persons' perspective. The goal should be to achieve the ‘best possible death given the circumstances’ (Holdsworth 2015) or a ‘good enough’ death (McNamara 2004) to reflect a death that satisfies realistic expectations (Raisio et al. 2015).

Locality was also identified as a critical element, with deaths and dying ideally to be connected with the rural/remote community. The literature increasingly reports that place of death is one measure of a contemporary ‘good death’ as supported by the majority of articles in this review; however as Biggs (2014) suggests, place is only one factor of importance and not necessarily the main one for all people (Hoare et al. 2015, Davies et al. 2016, Rainsford et al. 2016). If it is not possible to die at home surrounded by family then it is important to die within the rural community.

Knight (2014) suggests that the quality of dying is subjective and dependent on whose perspective one is using. Family and friends are thought to perceive a ‘good death’ has occurred when ‘timing, symptom management and support come together successfully’ (Adamson & Cruickshank 2013). Unfortunately due to heterogeneity within a small number of articles, it was not possible to compare the different perspectives of rural informants or to compare with any confidence the views of respondents in rich and poor countries; however, what was apparent is the different expectations as in Kenya one is focused on the ‘basics of life’ (Grant et al. 2003), whereas in Kansas, one fears ‘a technological death’ (Felt et al. 2000). Good pain control is highly ranked in EoLC (Byock et al. 2009); however, the difficulty of patients in developing countries accessing basic drugs such as morphine was highlighted.

Wilson et al. (2009a,b) found that rural people identify themselves as ‘rural’ with unique needs from urbanites; and dying in a rural area was reported to have elements that either enabled or obstructed a ‘good death’. These elements included distances, isolation, limited services and personnel, strong sense of community and resilience. As such, the findings of this scoping review are diverse, rich and informative, but not uniform across the countries or studies.

Study meaning

While adding to rural end-of-life knowledge by identifying and synthesising the current literature, this scoping review highlights the paucity of information relating to the ‘good’ rural death especially from the perspectives of dying patients and their family members. Only 20% of the rural informants identified in this review were patients or FCGs, with the majority having a cancer or HIV/AIDS diagnosis, yet ‘to remain socially relevant, EoLC ideally must reflect the needs of (all) the dying individuals … within diverse cultural and geographic areas’ (Cottrell & Duggleby 2016, p. 26). It is not just the rural voice that is as yet unheard and unrecognised as unique, but those with a non-malignant diagnosis as well as minority groups within rural communities. However, the findings of this review may be used to inform future researchers and policy makers of the ‘quiet’ rural voice and guide future planning and development of rural EoLC.

Limitations

This scoping review had limitations in the completeness of the review and the quality of identified studies. Studies not including the selection criteria wording in the title, abstract or keywords may have been missed; however, electronic searching was augmented by hand-searching journals and reference lists. A potential bias in data extraction, synthesis and analysis is also possible due to most authors being Palliative Medicine Specialists and/or General Practitioners and all citizens of western nations. Currently, there is no broad consensus on scoping review reporting guidelines, which potentially limits the report.

A more serious limitation is the lack of homogeneity and consistency in the ‘rural’ definition. This meant that studies reported on a variety of rural locations and rural populations. Extremely remote areas were not studied, although some of the rural peoples studied may have been in extremely remote areas with limited health services. Equally significant is the diversity in cultural perspectives. While this is a strength in that it presents a wide range of perspectives on the ‘good death’, it is also a limitation as it reduces the ability to examine the specific understanding of the ‘good death’ within diverse cultures.

The objectives of some studies were not ‘good death’ focused, a factor that increased the risk of our misinterpretation of the findings. Other limitations include small rural sample size; inability to determine perspectives of rural informant subgroups; limited generalisability; recruitment biases; a predominantly Christian or traditional cultural viewpoint; and variations in terminology.

Conclusion

Previous studies have found that rural residents consider themselves rural and as such have unique EoLC needs and challenges. The existence of 20 papers indicates that rural perspectives on the ‘good death’ are important to consider. The current literature is heterogeneous and thus insufficient to confidently generalise the perspectives of rural residents on the ‘good death’ and what it means to die well and to avoid dying badly. Rural residents of both developed and developing nations want a dignified death; however, this is largely subjective and thus open to interpretation based on personal, cultural, social and religious perspectives that could be highly individualised, family contextualised or rural community based. Clearly, given the importance of a ‘good death’, there is a need for further studies, both qualitative and quantitative, to elicit rural person, especially dying patients and family caregivers' perspectives.

Author contribution

SR was responsible for conception; design; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting, revising and final manuscript. RDM, DW, NJG contributed to review design. All co-authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data; revising the article critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.