Factors promoting resident deaths at aged care facilities in Japan: a review

Abstract

Due to an increasingly ageing population, the Japanese government has promoted elderly deaths in aged care facilities. However, existing facilities were not designed to provide resident end-of-life care and the proportion of aged care facility deaths is currently less than 10%. Consequently, the present review evaluated the factors that promote aged care facility resident deaths in Japan from individual- and facility-level perspectives to exploring factors associated with increased resident deaths. To achieve this, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Web of Science and Ichushi databases were searched on 23 January 2016. Influential factors were reviewed for two healthcare services (insourcing and outsourcing facilities) as well as external healthcare agencies operating outside facilities. Of the original 2324 studies retrieved, 42 were included in analysis. Of these studies, five focused on insourcing, two on outsourcing, seven on external agencies and observed facility/agency-level factors. The other 28 studies identified individual-level factors related to death in aged care facilities. The present review found that at both facility and individual levels, in-facility resident deaths were associated with healthcare service provision, confirmation of resident/family end-of-life care preference and staff education. Additionally, while outsourcing facilities did not require employment of physicians/nursing staff to accommodate resident death, these facilities required visits by physicians and nursing staff from external healthcare agencies as well as residents' healthcare input. This review also found few studies examining outsourcing facilities. The number of healthcare outsourcing facilities is rapidly increasing as a result of the Japanese government's new tax incentives. Consequently, there may be an increase in elderly deaths in outsourcing healthcare facilities. Accordingly, it is necessary to identify the factors associated with residents' deaths at outsourcing facilities.

What is known about this topic

- Ageing countries must ensure sufficient places of death for elderly people.

- In Japan, burgeoning healthcare expenditures and decreasing birth rate make it difficult for hospitals and homes to accommodate increasing death rates.

- The Japanese government has made efforts to promote deaths in aged care facilities. However, little is known about what factors accommodate in-facility deaths.

What this paper adds

- Healthcare provision, end-of-life care preference and confirmation staff education facilitates increased in-facility deaths.

- Healthcare outsourcing facilities must co-ordinate with external agencies that employ numerous medical staff.

- These findings are useful for policy discussions about necessary aged care capabilities for in-facility deaths in Japan and other countries.

Introduction

Due to population ageing, the mortality rate is increasing in developed countries (United Nations, 2012). These countries are examining how to ensure sufficient places of death for elderly people (WHO 2004, The OECD Health Project 2005, Gomes & Higginson 2008, Houttekier et al. 2011). Japan is the most rapidly ageing country. The number of deaths is projected to increase from 1.27 million in 2013 to 1.66 million in 2040 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2006). The Japanese government must ensure sufficient places of death for elderly people in the near future.

In Japan, hospitals are the most common place of death; the proportion of all hospital deaths was approximately 76.3% in 2012 (MHLW 2013c). The number of hospital beds per 1000 population is higher than other countries: 13.4 in Japan, and 4.6 in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries (OECD 2014). To contain elderly healthcare expenditures, the Japanese government attempted to reduce hospital beds from 1.34 million in 2013 to 1.15–1.19 million in 2025 (Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet 2015). More than half of Japanese people prefer to die at home, similar to other countries: 55% in Japan, 63% in the UK, 73–92% in the US (Cabinet Office Japan 2012, Gomes et al. 2012, 2013). However, in Japan, it is difficult to ensure that a caregiver is available because of the ageing population, decreasing birth rate and increasing number of households consisting only of individuals aged 65 or older (MHLW 2012b, Statistics and Information Department 2014, Cabinet Office Japan 2015).

These circumstances have led the Japanese government to ensure sufficient death places by promoting aged care facilities to accommodate resident deaths. There are seven types of facilities in Japan (Table 1). The facilities are classified into two groups based on healthcare service provision at resident's end-of-life (EOL): healthcare insourcing or outsourcing. Based on the long-term care (LTC) Insurance Act, healthcare insourcing facilities are required to employ physicians and/or nursing staff and provide healthcare and LTC services. Long-term care health facilities and intensive care homes for elderly people are classified into this group. Long-term care health facilities (also translated as geriatric health services facility or geriatric intermediate care facility) are rehabilitation facilities between hospital and home (Watanabe et al. 1999, Nakanishi et al. 2014, Ishii et al. 2016). They have fewer opportunities for residents' in-facility deaths because their residents discharge after shorter periods than other facilities (MHLW 2010). Intensive care homes (also translated as nursing home or special nursing home) are daily life facilities for elderly people who require constant care services. These have higher death rates of residents than other facilities because the facility does not require discharge after short periods and provides healthcare and LTC at EOL covered by LTC insurance (Ikegami & Ikezaki 2013, Nakanishi et al. 2014).

| Healthcare insourcing facilities | Insourcing/outsourcing facilities divided by type | Healthcare outsourcing facilities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term care health facilities [Kaigo rojin hoken shisetsu]a | Intensive care homes for elderly people [Tokubetsu yogo rojin homu]a | Care facilities for elderly people [Yogo rojin homu]a | Moderate-fee homes for elderly people [Keihi rojin homu]a | Fee-based homes for elderly people [Yuryo rojin homu]a | Elderly housing with care services [Sabisutsuki koreisya muke jutaku]a | Group homes for elderly persons with dementia [Gurupu homu]a | |

| Basic characteristics | Rehabilitation facilities to return elderly persons requiring long-term care to their homes | Daily life facilities for use by elderly persons who require long-term care | Facilities that admit environmentally and economically deprived elderly persons | Housing for elderly people with low incomes | Housing for elderly persons: provide bath/excretion/meal care, housework and long-term care | Housing for elderly persons: provide services such as check-up visits and daily life consultation. | Shared housing for elderly persons with dementia |

| Ownership | Local government/Non-profit | Local government/Non-profit | Local government/Non-profit | Local government/Profit/Non-profit | No restriction (Mainly profit) | No restriction (Mainly profit) | No restriction (Mainly profit) |

| Death rate | 7.0%b | 67.2%b | [Type: Care-Service Insourcing] | 22.8%b | |||

| -c | -c | 51.7%d | 36.5%d | ||||

| [Type: Care-Service Outsourcing] | |||||||

| -c | -c | 36.6%d | 29.8%d | ||||

| Criteria for staff placement |

Physicians: full-time; 100:1 or over Nursing staff and care workers: 3:1 or over |

Physicians: As required (possibility of part-time) Nursing staff and care workers: 3:1 or over Nursing staff: 100:3 or over |

[Type: Care-Service Insourcing] Physicians: - Nursing staff and care workers: 3:1 or over Nursing staff: 100:3 or over |

Physicians: - Nursing staff: - Care workers: 3:1 or over |

|||

|

[Type: Care-Service Outsourcing] Physicians: - Nursing staff: - |

|||||||

| Eligible persons | Persons requiring long-term care for physical or mental disabilities who have difficulty receiving in-home care. | Persons aged 65 or older who require constant care as the result of serious health issues. | Persons aged 65 or older who have difficulty receiving nursing care at home for environmental and economic reasons. | Persons aged 60 or older, certified as being unsure about living an independent life because of diminished body functions, among others and having difficulty receiving support from their family. |

Elderly persons Because no definition is provided for elderly persons under the Act for the Welfare of the Aged, the interpretation is based on general social norms. |

Single person/married couple households who are either:

|

Persons with dementia requiring long-term care/support. Excludes cases when diseases responsible for causing dementia are acute conditions. |

| Number of beds (year) | 266,700 (2003)→344,300 (2012) | 342,900 (2003)→498,700 (2012) | 66,970 (2003)→65,433 (2011) | 77,374 (2003)→91,786 (2011) | 55,448 (2003)→315,678 (2012) | Established in 2011→156,650 (2014) | 45,400 (2003)→170,800 (2012) |

- Revised situation and future direction for the Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2013a).

- a Japanese facility name.

- b Mizuho Information & Research Institute 2014.

- c Data were not found.

- d Nomura Research Institute 2015: Death rate was calculated by number of deaths in the facility/number of discharges from facility.

While outsourcing facilities can provide long-term or daily life support services, they do not generally provide healthcare services; the Act does not require physicians/nursing staff employment. Thus, residents living at outsourcing facilities receive healthcare services from visiting nurse agencies or home care support clinics (HCSCs) in communities (‘external agencies’). In Japan, external agencies play a central role in providing terminal home care services (Akiyama et al. 2012). These agencies can deliver healthcare services to residents of outsourcing facilities. Group homes for elderly people with dementia are small shared housing for elderly people with dementia (5–9 persons) that provide LTC care and daily life support in a home-like atmosphere (Nakanishi et al. 2014, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2014). Care facilities for elderly people and moderate-fee homes for elderly people are facilities for economically deprived elderly people; elderly people with low income have high priority for admission (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2014). Fee-based homes for elderly people and elderly housing with care services are housing that provide LTC or daily life support services. Most of the latter two facilities are run by the private-profit sector. When elderly people admit to the facilities with a contract, they must pay the full expense of the services (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2014). These facilities have about 20–50% death rates. Typically, the facilities are allowed to register as insourcing facilities by employing nursing staff. These facilities make a choice between outsourcing and insourcing types.

To promote dying in aged care facilities, the Japanese government provided new financial incentives in the medical/LTC insurance fee schedule. For insourcing facilities, a bonus is paid if aged care facilities meet certain requirements and provide residents with EOL care. In outsourcing facilities, the facility and/or external agency receives a bonus if they provide resident EOL care (MHLW 2006a,b, 2009, 2012a). This approach had the desired effect; the number of deaths at aged care facilities increased more than threefold, from about 26,000 in 2003 to about 91,000 in 2013 (MHLW 2013c).

However, aged care facilities were not designed to provide resident EOL care (MHLW 2013a). Although facility deaths are increasing, this proportion only accounts for 7% of deaths (MHLW 2013c). As aged care facilities will receive an increasing number of deaths, it is necessary to explore factors that accommodate resident deaths in these facilities.

Few studies have reviewed the factors necessary for accommodating in-facility resident deaths. Murray et al. (2009) reviewed predictors of individuals who received EOL cancer care at nursing homes. Specifically, they reported that the following factors affected receipt of nursing home EOL care: ‘women’, ‘older age’, ‘solid tumours’, ‘low functional status’, ‘poor overall global health’, ‘poor cognitive/social functioning’, ‘symptoms’, ‘lack of hospital proximity’, ‘previous homecare functioning’ and ‘no living spouse’. While this review clarified the factors related to receiving EOL care, it did not focus on factors related to in-facility deaths. Furthermore, this review analysed individuals, identifying individual-level factors. However, these studies have difficulty examining specific facility-level characteristics required to accommodate resident deaths. To explore these factors, it is necessary to observe the facility unit as an object and identify facility-level factors. Clarifying facility-level factors enables the government or aged care facility directors to understand what facility capabilities contribute to resident deaths.

Additionally, confirming individual-level factors related to deaths in aged care facilities provides increased understanding of facility-level factors from residents' perspectives. For instance, the association between solid tumours or low functional status and receipt of EOL care suggests it is logical to presume that facility capabilities (e.g. employment of staff who can provide healthcare) are needed to accommodate resident deaths.

However, few reviews focus on both facility- and individual-level factors that allow for resident deaths in aged care facilities. What facility capabilities promote in-facility deaths? This review explored the factors associated with increased resident deaths.

Method

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they identified facility-level factors that facilitated resident deaths in aged care facilities and identified individual-level factors associated with facility deaths. Additionally, studies were included if they identified external agency-level factors related to home deaths. This was essential because it is necessary for outsourcing facilities to co-ordinate with external agencies.

Exclusion criteria were studies that did not focus on related factors, exclusively assessed patients with specific diseases, or were reviews, commentaries, editorials and papers not written in English or Japanese.

Search methods

In January 2016, we searched four electronic databases: MEDLINE (1950–2016), CINAHL (1937–2016), Web of Science (1900–2016) and Ichushi (1984–2016). Ichushi contains bibliographic citations and abstracts from biomedical journals and other serial publications published in Japan.

Studies identifying related factors were searched using the following keywords: (‘residential facilities’ OR ‘supporting housing’ OR ‘assisted living facility’ OR ‘group home’ OR ‘halfway house’ OR ‘home for the aged’ OR ‘nursing home’ OR ‘group living’ OR ‘service house’), (death OR dying OR die OR ‘end of life’ OR palliative OR terminal*), and (place OR site OR location). Studies of external agencies were searched using the following keywords: (‘community health services’ OR ‘home care agencies’ OR ‘home care services’ OR ‘home nursing’ OR ‘visiting nursing agency’ OR ‘home care supporting clinics’), and the death and place keywords. Comparable search terms were used for Japanese language studies. We also included forward and backward citation searches of shortlisted studies.

Quality assessment

Study quality was appraised using a scale adapted from the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for quality assessment (Wells et al. 2006). This instrument assesses the quality of non-randomised studies in three broad categories (patient selection [four criteria], comparability [two criteria] and assessment of outcome [three criteria]). In cross-sectional studies, only six of nine criteria could be utilised (3, 2, and 1 respectively). When a study conformed to an NOS criterion, one point was added.

All studies meeting inclusion criteria were assessed. Because this review's objective was to explore related factors, studies with lower points were included. Despite searching for original articles, a number of magazine reports were identified, especially when using the Ichushi database (Japan Medical Abstracts Society 2008). In such cases, quality was assessed using the NOS scale.

Data extraction

In studies of facility/agency-level factors, the following data were extracted and entered into tables: author(s), publication year, participants, NOS score and related factors. In individual-level studies, factors were extracted. Consistent with a previous model, studies identifying factors were classified into three groups: environmental, individual and illness-related factors (Gomes & Higginson 2006).

Quality assessment and data extraction were completed by the first author and checked by a co-author (YO and MK) independently. Differences in assessment or extraction were managed by discussion until consensus was reached.

Results

Eligible study characteristics

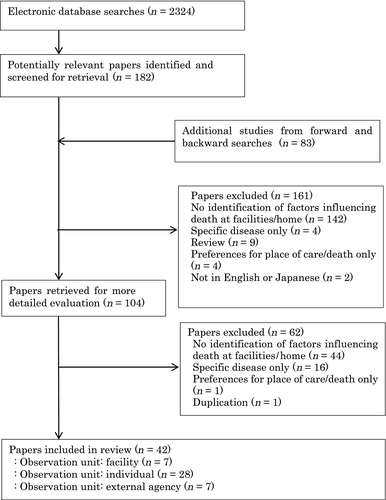

A total of 2324 articles were obtained from electronic searches and 42 papers were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Fourteen studies identified death-related factors at the facility/agency level and 28 identified individual-level death-related factors.

The 14 studies that identified facility/agency level-related factors had the following characteristics. All studies focused on Japan's aged care facilities or external agencies. Additionally, the number of studies increased over time. Thirteen studies used a cross-sectional design and one was longitudinal.

Five studies focused on insourcing facilities, two on outsourcing facilities and seven on external agencies. All insourcing facility studies conducted univariate analysis. Four of five studies calculated death rate as the outcome measure; one study identified whether the facility obtained the EOL care bonus. In outsourcing facility studies, only one study performed univariate analysis and the other utilised description and simple graphs. One used facility death rate as the outcome measure and the others identified EOL care provision until facility death. Of studies about external agencies, three performed multivariate analysis, four utilised univariate analysis and one described results using simple graphs. Six used housing death rate as the outcome measure and the others identified the number of deaths.

Overall, the quality of outsourcing facility studies was lower than insourcing facilities and external agencies, especially for ‘patient selection’ and ‘comparability’ criteria. Lower patient selection points were due to participant representativeness and lower comparability points were due to fewer appropriate independent variables and lack of multivariate analysis.

The 28 studies focused on individual-level, death-related factors were conducted in Japan, the US, Canada, Belgium, the UK, Europe, Germany, Australia and Sweden. Of these studies, multivariate analysis was most common; the most frequently dichotomised place of death was facility versus hospital or home.

Insourcing facility-level factors related to in-facility resident deaths (Table 2)

Environmental factors

Insource healthcare provision

Two high-quality studies (using nationwide randomised sampling) identified the following factors influencing high resident death rates: physician facility visits at night or on holidays; contact with part-time physicians rather than a co-ordinating hospital in emergencies; basic facility policy to accept individuals who are dying; and kind of available healthcare (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2003, Ikezaki & Ikegami 2012). Two medium-quality studies (using nationwide sampling, but with low response rates or number of sampled facilities from the selected area) supported the influence of co-ordination with medical staff including on-call shifts for nurses (Tsukada & Asami 2012, Shimada et al. 2013).

| Study characteristics | Death-related factors in the facility |

|---|---|

|

Institute for Health Economics and Policy (2003) Intensive care home for elderly people (N = 1730) NOS: 3/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

|

● Physician visits at night or on holidays ● In emergencies, contact part-time physician rather than co-ordinated hospital ● Kind of available healthcare (intravenous drip injection, tube feeding, oxygen therapy, monitoring of electrocardiogram (ECG), tracheotomy, central venous hyper alimentation, stoma treatment) ● Basic facility policy is care until death |

|

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

| ● Adjacent to hospital | |

| Confirming resident/family preference for EOL care | |

| ● Explanation of facility's basic policy | |

| Staff education | |

| ● Shared understanding about end-of-life (EOL) care among staff | |

| Facility characteristics | |

|

● Having a private room available for EOL care ● Long period since the facility's establishment |

|

|

Ikezaki and Ikegami (2012) Intensive care home for elderly people (N = 371) NOS: 3/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

| ● Basic facility policy is to accept patients who are dying | |

| Confirming resident/family preference for EOL care | |

| ● Documented preference for EOL care | |

|

Shimada et al. (2013) Intensive care home for elderly people (N = 389) NOS: 2/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

|

● Provides healthcare in the facility (tube feeding, oxygen therapy, intravenous drip injection, suction) ● Physician visits for death at night ● Nurse injection of nutrients in tube feeding ● Physician determines need for hospitalisation |

|

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

| ● Co-ordination with hospitals that can preferentially admit patients | |

| Confirming resident/family preference for EOL care | |

|

● Confirm preference for EOL care at deconditioning, readmission, EOL ● Explanation of the kind of healthcare that could be provided |

|

| Staff education | |

| ● Staff education about EOL care | |

| Illness-related factors | |

| ● Many residents in facility who meet criteria for EOL care bonus | |

|

Watanabe et al. (2010) Intensive care home for elderly people (N = 968) NOS: 2/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Confirming resident/family preference for EOL care | |

| ● Confirmation of resident or family advanced directives | |

|

Tsukada and Asami (2012) Intensive care home for elderly people (N = 38) NOS: 2/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

| ● On-call shift for nurses | |

| Staff education | |

| ● Implementation of staff education about EOL care | |

| Facility characteristics | |

| ● Having a private room available for EOL care | |

|

Konagaya (2010) Group home for elderly people with dementia (N = 2052) NOS: 1/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

|

● Physician visiting regularly ● Available hospital beds |

|

|

Institute for Health Economics and Policy (2005) Group home for elderly people with dementia (N = 825) NOS: 2/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Facility characteristics | |

| ● Long period since the facility's establishment | |

| Factors related to illness | |

| ● High-average level of care need |

- NOS, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Co-ordination with outsourced healthcare

Both high- and medium-quality studies identified that being adjacent to a hospital was associated with high death rates (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2003, Shimada et al. 2013).

Resident/family confirmation of EOL care preference

High-quality studies identified that factors associated with high death rates included documented preference for EOL care, explanation about a facility's basic policy or the kind of healthcare provided (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2003, Ikezaki & Ikegami 2012). A medium-quality study identified confirmation of EOL care preference at deconditioning, readmission and EOL as factors related to high death rates (Shimada et al. 2013).

Staff education

There was strong evidence that shared staff understanding about EOL care was associated with high death rates (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2003). Additionally, medium-quality studies identified that staff EOL care education was a factor associated with number of residents that met EOL care bonus billing criteria or high death rates (Tsukada & Asami 2012, Shimada et al. 2013).

Facility characteristics

There was strong evidence for association of high death rates with having a private room available for EOL care and long period since the facility's establishment (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2003).

Illness-related factors

A medium-quality study reported that having many residents who meet EOL care bonus criteria was associated with high-facility death rates (Shimada et al. 2013).

Individual factors

No studies identified related individual factors.

Outsourcing facility-level factors related to in-facility resident deaths (Table 2)

Environmental factors

Co-ordination with outsource healthcare

A low-quality study (sampled only facilities from medical or social welfare corporations) reported that available hospital beds and regular physician visits were related to EOL care provision until facility death (Konagaya 2010).

Facility characteristics

Long period since the facility's establishment was associated with high death rates in a medium-quality study (using nationwide randomised sampling, but describing results using simple graphs) (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2005).

Illness-related factors

A medium-quality study reported that a high-average resident care requirement was a factor related to high in-facility death rates (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2005).

Individual factors

No studies identified related individual factors.

External agency-level factors related to in-home resident deaths (Table 3)

| Study characteristics | Death-related factors in housing |

|---|---|

|

Kashiwagi et al. (2015) Visiting nurse agency (N = 69) NOS: 3/2/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

|

● Lack of attachment to a hospital ● Local Home Care Supporting Clinics (HCSCs) contractual relationship ● Systems of interactive information exchange through telephone/face-to-face communication between attending physicians |

|

|

Fukui (2012) Visiting nurse agency (N = 869) NOS: 3/2/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

|

● Meets the criteria for the around-the-clock care bonus ● More than four newly contracted users per month ● More than two users visited more than four times ● Less than 30% of users visited for less than 30 minutes among users with long-term care (LTC) insurance ● More users visited more than four times in a month since discharge |

|

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

|

● More than three orders for the visiting nursing from home care supporting clinics per a month |

|

| Illness-related factors | |

|

● Less than 30% of users with medical insurance ● More than 30% of user that scored C rank for degree of independent living |

|

|

Sugimoto et al. (2003) Visiting nurse agency (N = 1114) NOS: 2/2/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

| ● Positive attitude of physicians towards EOL care | |

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

|

● Relationship with co-ordinating hospitals: no relationship with funds or personnel ● Kind of hospitals with high orders for the visiting nurses: no beds ● Availability of hospitals beds during emergency: difficult ● Order occupancy for visiting nursing from a medical institution: less than 50% |

|

| Confirming resident/family preference for EOL care | |

| ● Implementation rate of confirming preference for EOL care: 50% or over | |

| Facility characteristics | |

| ● Characteristics of visiting area: rural | |

|

Fujikawa et al. (2011a) Visiting nurse agency (N = 259) NOS: 2/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

|

● Many visits ● Many visits outside of work hours ● Kind of available healthcare: home total parenteral nutrition, home hypodermic injection |

|

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

|

● Many contracts with HCSCs ● Contents of exchanged information with home care supporting clinics: treatment, patient or family preference for long-term care, kind of long-term care provided, dying in the home, medical supplies, medical equipment ● Contents of information exchanged with clinics other than home care supporting clinics: requests for home visit, dying in the home ● High frequency of meetings with hospital staff ● Kind of occupation co-ordinated: care manager, home-helper, agency providing home visit bathing, medical equipment agency |

|

| Facility characteristics | |

| ● Ownership of the agency: medical | |

|

Kumagai and Tabuchi (2014) Visiting nurse agency (N = 27) NOS: 1/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

|

● Agency occupation other than nurse: clerk ● Many nurses converted to regular employees |

|

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

| ● Many contracted physicians or medical institutions | |

| Factors related to illness | |

| ● Users who meet criteria for the EOL care bonus | |

|

Fujikawa et al. (2011a) Visiting nurse agency (N = 55) NOS: 1/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Co-ordination with outsource healthcare | |

| ● Orders for visiting nursing from HCSCs | |

|

Matsuki and Hasumoto (2012) HCSCs (N = 1) NOS: 1/0/1 |

Environmental factors |

| Insource healthcare provision | |

| ● Many physicians (increase from one to two in 2008) |

Environmental factors

Insource healthcare provision

Two high-quality studies (using nationwide randomised sampling, multivariate data analysis and/or high response rate) identified the following factors influencing high housing death rates: around-the-clock user visits; high number of user visits, especially in the month following discharge (Fukui 2012); and positive physician attitudes towards EOL care (Sugimoto et al. 2003). A medium-quality study (sampled facilities from selected area and used univariate analysis) reported high housing death rates were related to available healthcare type (e.g. total home parenteral nutrition and home hypodermic injection; Fujikawa et al. 2011a). Additionally, low-quality studies (sampled facilities from selected areas or clinical chart reviews, used univariate analysis or simple descriptive graphs) reported that employment of many physicians or nurses was associated with in-home deaths (Matsuki & Hasumoto 2012, Kumagai & Tabuchi 2014).

Co-ordination with outsource healthcare

The following factors were supported by high-quality evidence for their association with high death rates: systems of interactive information exchange between medical institution staff (Kashiwagi et al. 2015); lack of hospital availability (Sugimoto et al. 2003, Kashiwagi et al. 2015); and many HCSC orders for nurse visits (Fukui 2012). In Japan, visiting nurse agencies are required to receive orders for nursing visits from co-ordinated medical institutions. Regarding high home death rates, Sugimoto et al. (2003) reported that medical institutions undertook less than 50% of all orders received in a visiting nurse agency. A medium-quality study reported that the kind of service co-ordinated (care manager, home-helper, home visit bathing, medical equipment) was significantly associated with high housing death rates (Fujikawa et al. 2011a).

Confirming resident/family EOL care preference

A high-quality study reported that a 50% or higher implementation rate of confirmation of EOL care preference was associated with high death rates (Sugimoto et al. 2003).

Facility characteristics

A high- and a medium-quality study reported the following facility-related factors associated with high home death rate: rural visiting area (Sugimoto et al. 2003) and medical corporation visiting nurse agencies (Fujikawa et al. 2011a).

Illness-related factors

A high-quality study identified that contracting many users who were severely dependent in activities of daily living (ADL) was related to high death rates (Fukui 2012).

Individual factors

No studies identified related individual factors.

Individual-level factors related to in-facility deaths (Tables 4-6)

| Country | Environmental factors |

|---|---|

| Japan (n = 4) | Healthcare input |

| Presence of full-time physician in facility (Takezako et al. 2007), Doctors on call at night and makes in-person visits (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005), Doctors on call at night and responds on the phone (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005), Nurses make in-person visits outside work hours (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005), Basic policy to accept end-of-life (EOL) care in facility (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012), Frequency of meetings for EOL care (Hirano et al. 2011), Contracting with physicians belong to home care supporting clinic (Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012) | |

| US (n = 1) | Region characteristics |

| High Medicaid rate in region (Gruneir et al. 2007), Low-income level in region (Gruneir et al. 2007), More residential beds in region (Gruneir et al. 2007), Low percentage of persons 65+ years of age (Gruneir et al. 2007) | |

| Canada (n = 3) | Healthcare input |

| Hospital bed availability (Motiwala et al. 2006) | |

| Facility characteristics | |

| Nursing home size: large (McGregor et al. 2007), For profit (McGregor et al. 2007, Menec et al. 2009) | |

| Belgium (n = 1) | Region characteristics |

| More hospital beds in region (Houttekier et al. 2011) | |

| UK (n = 2) | Facility characteristics |

| Far distance from facility to country hospital (Gatrell et al. 2003) | |

| Region characteristics | |

| Rural environment (Evans et al. 2014), More residential beds in region (Evans et al. 2014) | |

| Europe (n = 2) | Region characteristics |

| More/fewer hospital beds in region (Houttekier et al. 2010b), More residential beds in region (Houttekier et al. 2010b), Country of residence (Houttekier et al. 2010a,b) | |

| Germany (n = 1) | Region characteristics |

| Rural environment (Dasch et al. 2015) | |

| Sweden (n = 1) | Region characteristics |

| Rural environment (Hakanson et al. 2015) |

| Country | Illness-related factors |

|---|---|

| Japan (n = 3) | Non-pneumonia (Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012), Severely dependent ADL (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Takezako et al. 2006), Severely impaired cognitive function (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005), Heart disease (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005) |

| US (n = 2) | Cancer (Levy et al. 2012), Non-diabetes (Levy et al. 2012), HIV (Weitzen et al. 2003), Non-COPD (Weitzen et al. 2003), Non-pneumonia (Weitzen et al. 2003), Severely dependent ADL (Weitzen et al. 2003), Severely impaired cognitive function (Levy et al. 2012), Non-heart disease (Levy et al. 2012) |

| Canada (n = 5) | Cancer (Motiwala et al. 2006), Non-cancer (Motiwala et al. 2006), Non-pneumonia (Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Dementia (Motiwala et al. 2006, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Non-heart disease (Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Non-cerebrovascular (Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Eating problems (Krishnan et al. 2015), Severely impaired cognitive function (Krishnan et al. 2015), Severely dependent ADL (McGregor et al. 2007, Menec et al. 2009, Krishnan et al. 2015), No organ failure (Menec et al. 2009) |

| Belgium (n = 3) | Non-cancer (Houttekier et al. 2009, 2011), Dementia (Cohen et al. 2006) |

| UK (n = 2) | Non-cancer (Evans et al. 2014), Non-pneumonia (Evans et al. 2014), Severely impaired cognitive function (Perrels et al. 2014), Non-heart disease (Evans et al. 2014), Non-cerebrovascular (Evans et al. 2014) |

| Europe (n = 1) | Dementia (Houttekier et al. 2010b) |

| Germany (n = 1) | Non-cancer (Dasch et al. 2015), Dementia (Dasch et al. 2015) |

| Sweden (n = 1) | Dementia (Hakanson et al. 2015), Non-heart disease (Hakanson et al. 2015), Non-digestive disease (Hakanson et al. 2015), Non-respiratory disease (Hakanson et al. 2015), Non-endocrine disease (Hakanson et al. 2015), Non-infection disease (Hakanson et al. 2015) |

- ADL, activities of daily living; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Country | Individual factors |

|---|---|

| Japan (n = 6) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (Miyahara 1999, Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Takezako et al. 2006, 2007, Hirano et al. 2011), Female (Takezako et al. 2006) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Resident prefers to die in the nursing home (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005), Family prefers resident die in the nursing home (Takezako et al. 2007, Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012), Agreement among family members about facility death (Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012), Resident does not prefer to die in the hospital (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005), Lower hospitalisation rate prior to death (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Hirano et al. 2011), Long-term stay (Takezako et al. 2006) | |

| US (n = 4) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (Solloway et al. 2005, Gruneir et al. 2007, Weitzen et al. 2003), Female (Solloway et al. 2005, Gruneir et al. 2007), Single/Widowed/Divorced (Solloway et al. 2005, Gruneir et al. 2007), Race/Ethnicity: white people (Gruneir et al. 2007, Weitzen et al. 2003), Religion: Roman Catholic (Solloway et al. 2005) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Low educational level (Gruneir et al. 2007), No caregiver (Weitzen et al. 2003), Medicaid (Solloway et al. 2005), Lower hospitalisation rate prior to death (Pekmezaris et al. 2004), Any advanced directive (Pekmezaris et al. 2004, Levy et al. 2012), Long-term stay (Levy et al. 2012) | |

| Canada (n = 5) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (McGregor et al. 2007, Menec et al. 2009, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Female (McGregor et al. 2007, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Single/Widowed (Jayaraman & Joseph 2013) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Recent immigrant (Motiwala et al. 2006), Lower socioeconomic status (Motiwala et al. 2006), Recent year of death (Jayaraman & Joseph 2013), Advanced care planning: no resuscitation (Krishnan et al. 2015), Long-term stay (Menec et al. 2009) | |

| Belgium (n = 3) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (Cohen et al. 2006, Houttekier et al. 2009, 2011), Female (Cohen et al. 2006, Houttekier et al. 2011) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Higher socioeconomic status (Houttekier et al. 2009), Low educational level (Cohen et al. 2006, Houttekier et al. 2011), Recent year of death (Houttekier et al. 2011) | |

| UK (n = 3) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (Gatrell et al. 2003, Evans et al. 2014, Perrels et al. 2014), Female (Gatrell et al. 2003, Evans et al. 2014), Single/Divorced (Evans et al. 2014) | |

| Europe (n = 1) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (Houttekier et al. 2010b), Female (Houttekier et al. 2010b) | |

| Germany (n = 2) | Demographic variables |

| Older age (Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011, Dasch et al. 2015), Female (Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011, Dasch et al. 2015), Single/Widowed/Divorced (Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Lower socioeconomic status (Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011), Low educational level (Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011), Relatives have full-time job (Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011) | |

| Australia (n = 1) | Demographic variables |

| Female (Roder et al. 1987) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Recent year of death (Roder et al. 1987) | |

| Sweden (n = 1) | Demographic variables |

| Female (Hakanson et al. 2015), Single (Hakanson et al. 2015) | |

| Personal variables | |

| Low educational level (Hakanson et al. 2015) |

Individual-level studies had the following characteristics. Countries included the US, Belgium, the UK, Germany, Canada, Japan, Europe and Sweden. The facility reference points included care homes, nursing homes, residential homes, LTC facilities, extended care facilities and community living centres. They also compared place of death (hospital; home: with or without homecare; and non-facility), and used different study samples (general population, facility residents) and analysis methods (multivariate, univariate).

Environmental factors (Table 4)

Environmental facility characteristics related to in-facility resident deaths were reviewed from residents' perspectives. The following factors indicate the facility characteristics for individual deaths.

Healthcare inputs

Individual-level healthcare input studies reported that the following factors were associated: presence of a full-time facility physician (Takezako et al. 2007); nurses making in-person visits outside work hours (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005); basic facility policy to accept EOL care (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012); facility co-ordination with physicians belong to HCSCs (Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012); and high frequency of EOL care-related meetings (Hirano et al. 2011). These studies utilised multivariate analysis with place of death dichotomised as nursing homes versus hospitals.

Facility characteristics

Identified facility-related characteristics included large nursing home size (McGregor et al. 2007); for-profit facility ownership (McGregor et al. 2007, Menec et al. 2009); hospital bed availability (Motiwala et al. 2006); and distance from facility to hospital (Gatrell et al. 2003). These studies utilised multivariate analysis. Gatrell et al. (2003) dichotomised place of death as nursing home versus ‘elsewhere’; the other studies compared place of death with hospitals.

Regional characteristics

More residential beds in a region (Gruneir et al. 2007, Evans et al. 2014); rural environment (Evans et al. 2014, Dasch et al. 2015, Hakanson et al. 2015); and country of residence (Houttekier et al. 2010a,b) were reported as factors in multiple studies. Two studies reported an association between hospital beds and place of death. While one study found that more hospital beds were associated with facility deaths (Houttekier et al. 2011), another reported that beds had a negative effect on hospital deaths and a positive effect on home deaths (Houttekier et al. 2010b).

Illness-related factors (Table 5)

Multiple studies reported the following factors: dementia or severely impaired cognitive function (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Cohen et al. 2006, Motiwala et al. 2006, Houttekier et al. 2010b, Levy et al. 2012, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Perrels et al. 2014, Dasch et al. 2015, Hakanson et al. 2015, Krishnan et al. 2015); severely dependent ADL (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Takezako et al. 2006, McGregor et al. 2007, Menec et al. 2009, Weitzen et al. 2003, Krishnan et al. 2015); non-respiratory disease (Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Weitzen et al. 2003, Evans et al. 2014, Hakanson et al. 2015); and non-cerebrovascular disease (Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Evans et al. 2014). Nine studies reported cancer and heart disease, but the effect on place of death differed (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Motiwala et al. 2006, Houttekier et al. 2009, 2011, Levy et al. 2012, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Evans et al. 2014, Dasch et al. 2015, Hakanson et al. 2015). Multivariate analysis was most common and the most frequently dichotomised place of death was facility versus hospital.

Individual factors (Table 6)

Demographic variables

Older age (Miyahara 1999, Gatrell et al. 2003, Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Solloway et al. 2005, Cohen et al. 2006, Takezako et al. 2006, 2007, Gruneir et al. 2007, McGregor et al. 2007, Houttekier et al. 2009, 2010b, 2011, Menec et al. 2009, Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011, Hirano et al. 2011, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Weitzen et al. 2003, Evans et al. 2014, Perrels et al. 2014, Dasch et al. 2015); female sex (Roder et al. 1987, Gatrell et al. 2003, Solloway et al. 2005, Cohen et al. 2006, Takezako et al. 2006, Gruneir et al. 2007, McGregor et al. 2007, Houttekier et al. 2010b, 2011, Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Evans et al. 2014, Dasch et al. 2015, Hakanson et al. 2015); race (Gruneir et al. 2007, Weitzen et al. 2003); and single/widowed/divorced marital status (Solloway et al. 2005, Gruneir et al. 2007, Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013, Evans et al. 2014, Hakanson et al. 2015) were factors for in-facility death in multiple studies from various countries. There were no contradictory findings between studies on demographic variables.

Personal variables

The following factors were reported: low educational level (Cohen et al. 2006, Gruneir et al. 2007, Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011, Houttekier et al. 2011, Hakanson et al. 2015); lower number of hospitalisations prior to death (Pekmezaris et al. 2004, Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Hirano et al. 2011); recent year of death (Roder et al. 1987, Menec et al. 2009, Houttekier et al. 2011, Jayaraman & Joseph 2013); resident/family prefers nursing home death (Shinoda-Tagawa & Ikegami 2005, Takezako et al. 2007, Ikegami & Ikezaki 2012); any advanced directive (Pekmezaris et al. 2004, Levy et al. 2012); and long-term stay (Takezako et al. 2006, Levy et al. 2012). Four studies reported differential effects of place of death and socioeconomic status (high or low). Multivariate analysis was most common and the most frequently dichotomised place of death was facility versus hospital (Motiwala et al. 2006, Houttekier et al. 2009, Escobar Pinzon et al. 2011).

Discussion

Our findings provide organised information necessary for discussion on the capability of aged care facilities to accommodate in-facility deaths. First, healthcare service provision, confirmation of resident/family EOL care preferences and staff education had an important impact on residents' facility deaths. Second, some individual-level factors associated with facility deaths were common in various countries. These will be useful items for adjusting the number of in-facility resident deaths. Finally, a study implication is that research identifying factors associated with death at healthcare outsourcing facilities is required.

First, the capability of aged care facilities to accommodate in-facility deaths is described with regard to insourcing and outsourcing facilities respectively.

Insourcing facilities

Initially, it is critical that healthcare service provision adequately copes with various residents' conditions at EOL. Specifically, high-quality studies reported that it was especially important that medical staff provide care at night/on holidays. In Japan, insourcing facilities are required to employ physicians and/or nursing staff. However, intensive care homes for elderly people often only employ these staff part-time. For example, the proportion of all facilities that employ a full-time physician, night shift nurse and had an existing system for physician visits at night/during holidays are only 5.0%, 5.2% and 50% respectively (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2003). Many facilities cannot ensure that physicians and/or nursing staff provide EOL care or death certification. This situation increases unnecessary hospitalisations immediately preceding residents' deaths. To increase in-facility deaths, promoting employment of medical staff at night/on holidays or developing co-ordination systems between part-time medical staff and other staff are necessary.

Next, confirmation of resident/family EOL preference is associated with in-facility resident deaths. Specifically, high-quality studies identified that explanations about a facility's basic EOL care policy and confirmation of residents' advanced directives or family/resident EOL care facilitated insourcing facility resident deaths. Explanations about the facility's basic EOL care policy may contribute to admission of individuals who prefer to remain in the facility until death. Previous studies from the US and Australia reported confirmation of resident/family EOL preference significantly reduced resident hospitalisation (Caplan et al. 2006, Arendts & Howard 2010). Confirmation of advanced care directives can prevent hospital transfer of residents who do not prefer hospital deaths and may increase residents' deaths in aged care facilities.

Finally, strong evidence indicated that shared staff understanding about EOL care and staff EOL education were necessary for residents to remain in the facility until death. Insourcing facilities employ professionals from various occupations (e.g. physicians, nurses, care workers). Lack of medical staff and care worker co-ordination was an inhibiting factor for in-facility resident deaths (Hashimoto & Ono 2014). Development of a shared understanding or staff education about EOL will contribute to resident EOL care provision by promoting co-ordination between occupations. Additionally, a previous study from the UK reported education programmes designed to improve EOL cares increased care home staff discussion of advanced care planning and improved collaboration with general practitioners (GPs) (Badger et al. 2012). Other studies also reported that staff education significantly raised in-facility death rates of elderly people with dementia (Livingston et al. 2013). Staff education may increase in-facility death through promoting co-ordination of medical staff and confirming resident/family EOL preference.

With the rapid ageing, Japanese government already produced a bonus that is paid if an insourcing facility provides EOL care co-ordinating with physicians or nurses, educating staff, and confirming resident/family EOL preferences. However, this review suggests the government also should consider promoting employment of medical staff at night/on holidays.

The present findings also indicate some issues in other developed countries will soon be facing similar situations on ageing. For examples, in the UK and US, Care Quality Commission (CQC) or Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) assess and regulate care quality of insourcing facilities. However, staff education and confirmation of resident/family preference for EOL are not included in the assessment frameworks, although their necessity has been mentioned (Caplan et al. 2006, Livingston et al. 2013). In addition, although medical staffing is assessed by the assessment frameworks, issues remain. Nursing care homes in the UK in particular are required to employ nursing staff, but the standards of nurse staffing for EOL care are not present. Furthermore, 20% of nursing care homes did not have sufficient staff on the duty (CQC 2014). The facilities are not required to employ physicians. Instead, co-ordination between the facility and GPs is promoted by The Gold Standards Framework or the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying; these are developed in the UK to improve EOL care in care homes (Ellershaw & Wilkinson 2003, Thomas & Sawkins 2008). However, nearly half of the care homes may not have completed implementation of The Gold Standards Framework because of difficulty for co-ordination with GPs (Badger et al. 2009, Hall et al. 2011). Additionally, the number of nursing care homes registered to Liverpool Care Pathway did not reach 600 (The Royal Liverpool University Hospital St Marie Curie Cancer Care 2009). To promote in-facility death, other countries also need to solve these issues.

Outsourcing facilities

Studies of outsourcing facilities found co-ordination with outsourced healthcare (regular physician visits, available hospital beds) necessary to facilitate in-facility deaths. While healthcare insourcing facilities are obligated to employ physicians and nursing staff, outsourcing facilities are not. Such differences in healthcare provision engender the necessity of co-ordination with outsourced healthcare. Outsourcing facilities receive healthcare aid from external agencies. Thus, this review also found the factors required by external agencies so that they can effectively contribute to aged care facilities accommodating residents' deaths.

Two factors were important for external agency care provision until residents' deaths. First are healthcare provision-related factors. Around-the-clock visits and receiving HCSC orders for nursing visits were especially associated with in-home deaths. Conversely, lack of hospital attachment and difficulty accessing hospitals beds during an emergency were associated with visiting nurse agency housing deaths. Kashiwagi et al. (2015) stated that ‘service users of hospital-attached visiting nurse agency might be more likely to be admitted to the attached hospital immediately in case of an emergency, and then to die in the hospital’ (p. 940). Thus, outsourcing facilities should value agency capability for nursing visits and must directly discuss how to transfer users to hospitals.

Another external agency-related factor is confirmation of resident/family advanced directives. The reason for this might be similar. The following factors promoted housing deaths: visiting nursing agencies receive many visiting orders from medical institutions or the agency is a medical corporation. These situations may make it easier to confirm advanced directives and provide users with EOL care.

In Japan, a bonus is paid if external agencies provide around-the-clock visits or confirm the patient's preference for EOL. However, there is no incentive for co-ordination between outsourcing facilities and external agencies. The Japanese government should consider promoting outsourcing facilities to co-ordinate with external agencies that employ numerous medical staff with positive attitudes towards EOL care, co-ordinate with medical institutions (especially HCSCs), conduct visits outside the typical workday and confirm users' advanced directives.

In the UK, the CQC assesses the quality of GP's EOL care provided for outsourcing facility residents (e.g. residential care homes). However, a previous study reported that the numbers of visits by GPs to the facilities' residents fell (Evans 2011). The government needs to examine the co-ordination between outsourcing facilities and GPs. The US government requires hospice agencies to provide medical, nursing, social work, chaplaincy, and bereavement support in around-the-clock for facility residents under Medicare (Morrison 2013). Additionally, the CMS assesses the quality of care (CMS 2016). In fact, hospice use in outsourcing facilities (assisted living) significantly reduces discharges to hospital or nursing home (Dobbs et al. 2012). However, hospice agencies' staffs reported difficulty in co-ordinating with outsourcing facilities' staff because the facility staff do not understand disease process and symptom management (Dixon et al. 2002). Nevertheless, nearly half of states do not require the outsourcing facility to employ medication assistance staff or to train unlicensed staff (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2015). To promote in-facility death, these states may need to improve comprehension of outsourcing facility's staff.

Second, studies observed individual-level factors associated with in-facility deaths. Specifically, older age, female sex, single/widowed/divorced marital status, severely dependent ADL, severely impaired cognitive function and low educational level were associated with in-facility deaths in studies from various countries. Regardless of differences between countries or their policies, these characteristics may make it difficult to continue to live at home or receive healthcare at hospitals.

Considering worldwide ageing, elderly people with these characteristics will increase globally; this situation will require evaluating facilities' death-related capabilities. Nevertheless, the present review found all studies of aged care facilities used univariate analysis. This suggests previous studies failed to identify the capabilities. Ageing countries should use multivariate analysis to adjust for these factors.

Finally, it is necessary to address this review's implications. Only two studies identified factors about outsourcing facilities' capability for resident deaths (Institute for Health Economics and Policy 2005, Konagaya 2010). These studies had lower NOS scores due to a lower number of appropriate independent variables and lack of multivariate analysis. It may not have been possible to identify the key factors. Most of the outsourcing facilities claim lower benefits from social security programmes than insourcing facilities. Thus, the Japanese government promote to expand outsourcing facilities with producing the new tax incentives and subsidies (MHLW 2013b). The ageing countries' governments are also implementing policies that reduce insourcing facilities and provide outsourcing facilities to satisfy the sustainability of social security system. Therefore, there may be an increase in elderly deaths in healthcare outsourcing facilities globally. Identification of factors related to the capability of these facilities for residents' deaths is required.

Furthermore, the reviewed studies investigating external agencies did not focus on visits to outsourcing facilities. Thus, factors pertaining to external agencies' capability to facilitate deaths in outsourcing facilities were unidentified.

Review limitations

The present review had some limitations. First, it only evaluated studies identifying factors associated with Japan's aged care facility capability at the facility level. Not all of the findings can be applied to other ageing countries' facilities. Many individual-level studies from other countries identified factors pertaining to home death, but facility death-related factors were only used to compare home or hospital death-related factors. Thus, in these countries, it may be most important to promote home death.

Second, this review evaluated facility-related factors associated with facilitating resident deaths. Consequently, most reviewed studies utilised death rate as the outcome measure. However, a facility's capability for EOL care cannot only be evaluated by measuring death quantity. Therefore, other reviews are necessary to provide knowledge about high-quality EOL care in aged care facilities.

Finally, the present review findings should be interpreted with care from following points: the low methodological quality of studies, potential publication bias and limited search to English and Japanese databases.

Despite these limitations, this is the first review exploring factors that enable in-facility resident deaths. Information about determining the number of possible deaths at aged care facilities will be pertinent to ageing countries other than Japan. Therefore, the present findings serve as a useful reference for policy discussions about the necessary aged care facility capabilities in terms of factors related to resident in-facility deaths in Japan and other countries.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported, in part, by a research grant provided by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Grant no. 26861960).

Principal investigator: Kentaro Sugimoto

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.