Patient–professional partnerships and chronic back pain self-management: a qualitative systematic review and synthesis

Abstract

Chronic back pain is common, and its self-management may be a lifelong task for many patients. While health professionals can provide a service or support for pain, only patients can actually experience it. It is likely that optimum self-management of chronic back pain may only be achieved when patients and professionals develop effective partnerships which integrate their complementary knowledge and skills. However, at present, there is no evidence to explain how such partnerships can influence patients' self-management ability. This review aimed to explore the influence of patient–professional partnerships on patients' ability to self-manage chronic back pain, and to identify key factors within these partnerships that may influence self-management. A systematic review was undertaken, aiming to retrieve relevant studies using any research method. Five databases were searched for papers published between 1980 and 2014, including Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO. Eligible studies were those reporting on patients being supported by professionals to self-manage chronic back pain; patients being actively involved for self-managing chronic back pain; and the influence of patient–professional partnerships on self-management of chronic back pain. Included studies were critically appraised for quality, and findings were extracted and analysed thematically. A total of 738 studies were screened, producing 10 studies for inclusion, all of which happened to use qualitative methods. Seven themes were identified: communication, mutual understanding, roles of health professionals, information delivery, patients' involvement, individualised care and healthcare service. These themes were developed into a model suggesting how factors within patient–professional partnerships influence self-management. Review findings suggest that a partnership between patients and professionals supports patients' self-management ability, and effective communication is a fundamental factor underpinning their partnerships in care. It also calls for the development of individualised healthcare services offering self-referral or telephone consultation to patients with chronic conditions.

What is known about this topic

- Self-management is a core principle to the control of pain and relevant functional problems.

- Patients in self-management are supported through a partnership with health professionals to make decisions and take actions to manage the pain.

- No systematically constructed evidence available that explains how such partnerships can influence patients' self-management ability.

What this paper adds

- Seven themes are identified influencing patient–professional partnerships and chronic back pain self-management.

- A combination of patients' experience and professionals' expertise should be considered when delivering self-management programmes.

- It is important for health professionals to be aware of patients' personal circumstances, and for healthcare organisations to develop individualised services to support patients with chronic pain.

Introduction

Chronic pain has been defined as a continuous, unpleasant experience that has occurred for more than 12 weeks (British Pain Society 2013). Chronic back pain as the most common type of chronic pain has a high incidence in the population. Chronic back pain may affect up to 80% of the United Kingdom (UK) population (NICE 2009). Approximately 1.6 million adults develop chronic back pain each year, and for around half of them the pain is disabling (Donaldson 2009). While suffering from chronic back pain, major clinical, social and economic problems can occur (Croft et al. 2010). However, for most people, there is no cure that can relieve the pain permanently. Patients living with it often spend many years seeking help, and sometimes get stuck in a cycle of visiting different specialists (Clare et al. 2013). Consequently, chronic back pain self-management which refers to ‘an ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition individually’ (Barlow et al. 2002, p. 178) is increasingly becoming a lifelong task. It is perceived as core to the control of pain and relevant functional problems (The Centre for Managing Chronic Disease 2011). Research has demonstrated that self-management is dependent on collaboration between patients and health professionals (Bodenheimer et al. 2002). Patients' self-management is often supported by health professionals in terms of providing them with relevant information and skills.

The nature of pain means that it is a subjective experience and can only be experienced by people who are living with it (Cremeans-Smith et al. 2003). Health professionals, on the other hand, are the experts in providing health services to promote healing of the body and mind but cannot manage the pain on behalf of their patients (Enehaug 2000). To better manage the pain and its related symptoms, a new era of developing partnerships between patients and health professionals is emerging, referring to ‘a co-operation or an alliance where people work together in mutual respect’ (Enehaug 2000, p. 178).

There have been several reviews on either chronic back pain self-management (Du et al. 2011, Oliveira et al. 2012) or patient–professional partnerships (Ridd et al. 2009), but none that focused on both. How partnerships would influence a patient's ability to self-manage the pain still remains unknown. The lack of evidence led to the decision to undertake this systematic review. The aim was to explore the influence of patient–professional partnerships on patients' ability to self-manage chronic back pain, and to identify key factors within these partnerships that may influence self-management. The findings of this review provide both patients who have chronic back pain and health professionals, with an understanding of patient–professional partnerships and the self-management of chronic back pain.

Method

Search strategy

Thorough and comprehensive searches were conducted using five electronic databases (Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO) from the year 1980 when self-management emerged as a priority for health science researchers to date (Rashiq et al. 2008). A range of keywords and subject headings representing patient–professional partnerships, chronic back pain and self-management were used aiming to maximise the retrieval of relevant studies (see Table S1 for details). Government publications and reports were also read. Reference lists and citation indexes of relevant articles were scrutinised, searching for titles which met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

- Patients were supported by having a partnership with health professionals to experience chronic back pain self-management.

- Patients were actively involved with health professionals in developing treatment or care plans for self-managing chronic back pain.

- The influence of patient–professional partnerships on chronic back pain self-management was reported.

Exclusion criteria

- Studies reporting views of the general public.

- Studies of patients undergoing cancer treatments or related therapies.

- Letters of opinion to peer-reviewed journals.

- Editorials or commentaries.

- Non-English language studies.

Study selection

Records identified from the electronic searches, government publications and websites, and reference lists were imported into Endnote X6 (Reuters 2011) to avoid duplication of the screening process (Moher et al. 2009). At the stage of screening, abstracts were retrieved if the title included reference to patient–professional partnerships and to chronic back pain self-management. If it was not clear from the title or the abstract, the full text was retrieved. Studies were excluded if they were clearly not full reports of their research, for example, conference abstracts, editorials or commentaries or news reports. Titles and abstracts were screened by the first author and checked by the co-authors. The included studies were also checked against the inclusion criteria by the co-authors independently. Whenever a disagreement occurred, we discussed until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the original studies into a table to present the characteristics of the studies included. Data included authors' names, the year when the study was published, country where the study was conducted, study design and aim, recruitment and sample, health condition that the study focused on, method of data collection and analysis, main findings and recommendations. Data extraction was completed by the first author and checked by the co-authors independently. When there was a question about the data extracted from studies, we discussed our opinions until consensus was reached.

Appraisal of studies

All studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for appraising qualitative research (CASP 2013). It consists of 10 questions that are designed to help researchers appraise qualitative studies systematically. It is easy to use, and the answers to these 10 questions indicate the trustworthiness, results and relevance of included studies. The answers ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Cannot tell’ were selected for each paper to indicate whether the CASP question had been extensively addressed, been addressed partially or not been addressed. We decided not to exclude studies of low quality, as quality assessment in this study was to help us identify errors and flaws, rather than criticise or challenge the original studies. In addition, a study may be of low quality because although it contained valuable findings, the interpretation was weak (Dixon-Woods et al. 2004, Pawson 2006). Previous literature also highlights that some studies provided good grounded insights into research questions, but had been written up poorly or briefly due to word length constraints so that some information had to be omitted (Seers & Toye 2012). Appraisal of the included studies was carried out by the first author and checked by the co-authors independently. Where there was a question about the identified themes, all three reviewers discussed until consensus was reached.

Synthesis of results

The studies included were all primary qualitative research, allowing synthesis of the findings. General debate continues on the appropriateness of combining qualitative studies and the methodological development of synthesising qualitative studies. Some have argued that the findings of individual qualitative studies were de-contextualised by synthesis and that those themes identified were not necessarily applicable to other studies (Britten et al. 2002). Various methods for synthesising qualitative studies in a systematic way are still emerging, for instance, meta-ethnography (Noblit & Hare 1988), grounded theory synthesis (Finfgeld 2003) and thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden 2008).

Here, we conducted a simple thematic synthesis to clarify the influence of patient–professional partnerships on patients' ability to self-manage chronic back pain, and to identify key factors within these partnerships that may influence self-management. Thematic synthesis was guided by the principles outlined by Thomas and Harden (2008). The 10 retrieved studies were read and re-read in-depth to explore how patient–professional partnerships could influence patients self-managing their back pain. Participants' (patients and health professionals) experiences, perceptions and the original authors' findings and conclusions were identified and recorded. With repeated readings of the studies, findings and themes were linked and further grouped to broader descriptive codes. These codes were then compared and contrasted across studies to generate new themes, which aimed to represent new interpretations of the findings of each included study and to further enable the development of a model illustrating the relationship between patient–professional partnerships and chronic back pain self-management. Data synthesis was carried out by the first author and checked by the co-authors independently. Where there was a question about the identified themes, all three reviewers discussed until consensus was reached.

Findings

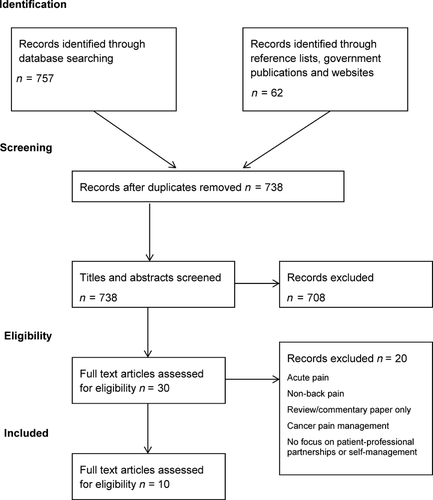

A total of 757 records were identified from the electronic search, and 62 records were identified through reference lists and government publications and websites. After duplicates were removed, 738 records were available for screening. Titles and abstracts for the 738 records were screened against the inclusion criteria, and 708 records were excluded. Thirty articles were retrieved in full text, and 20 of these were excluded as they referred to non-chronic back pain, cancer pain management or had no focus on patient–professional partnership or self-management (see Figure 1).

Although this review aimed to include relevant studies using any research method, all the included studies happened to be qualitative, using either focus groups or individual interviews. In total, they involved 223 patients and 11 health professionals, and reported a range of aspects of patient–professional partnerships and their influence on chronic back pain self-management, including self-management support, patients' education, patient-centredness in physiotherapy and partnership in care. Only one study focused on examining health professionals' perspectives (Jeffrey & Foster 2012), the others investigated patients' views of pain management. The characteristics of the 10 studies are summarised in Table S2.

The quality of the included studies was appraised using the CASP checklist. This checklist is not designed to provide a numerical score as a cut-off point to measure the quality of the studies. However, to provide a better understanding of quality appraisal, each study was given a summary quality rating: high, medium or low, according to the answers of the 10 questions (see Table S3 for details). Studies were rated based on the criteria shown below (see Table 1 for details).

| Summary quality rating | Answers for 10 CASP questions |

|---|---|

| High | 10 ‘Yes’; 1 ‘Cannot tell’ + 9 ‘Yes’ |

| Medium | 2 or 3 ‘Cannot tell’ + the rest are ‘Yes’; 1 ‘No’ + 0 or 1 or 2 or 3 ‘Cannot tell’ + the rest are ‘Yes’ |

| Low | 2 or more ‘No’ + the rest are ‘Yes’; 4 or more ‘Cannot tell’ + the rest are ‘Yes’ |

As a result of this, two studies were categorised as high quality, seven were medium and one was low. Studies were deemed to be of low quality mainly when there was insufficient information given to establish whether the research design was appropriate to address the research aim or to determine the justification of the research methods. Similarly, studies were designated low quality when they lacked information on the relationship between researchers and participants or in-depth description of the data analysis process.

The review and synthesis of the ten studies generated seven themes relating to patient–professional partnerships and chronic back pain self-management (in no particular order): communication, mutual understanding, health professionals' roles, information, patients' involvement, individualised care and healthcare service. Table 2 presents the appearance of the themes in each study, and a more detailed example illustrating how direct quotes from the included studies comprise these themes is shown in Table S4.

| Themes | Effective communication | Mutual understanding | Roles of health professionals | Information delivery | Patient involvement | Individualised care | Healthcare service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key terms | Communicate, talking, listening, face-to-face, telephone contact, language | Feeling understood, attitudes, beliefs, feelings of pain, life situation, trust | Emotion support, encouragement, motivation | Self-management strategies and skills, diagnosis, treatment | Participation, empowerment, agreement, decision-making, share responsibility | Personalised treatment, suitable for patients | Access to physiotherapy, time, resources, follow-up contact |

| Jeffrey and Foster (2012) | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Matthias et al. (2010) | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Matthias et al. (2012) | * | * | * | * | |||

| Cooper et al. (2008) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Cooper et al. (2009) | * | * | * | * | |||

| Östlund et al. (2001) | * | * | * | * | |||

| Slade et al. (2009) | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| May (2001) | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| MacKichan et al. (2013) | * | * | * | * | |||

| May (2007) | * | * | * |

Effective communication

Eight of the 10 studies emphasised the importance of communication between health professionals and patients with chronic back pain (May 2001, Östlund et al. 2001, Cooper et al. 2008, 2009, Slade et al. 2009, Matthias et al. 2010, 2012, Jeffrey & Foster 2012). In particular, patients perceived it as fundamental in their partnerships with health professionals, and believed that it could contribute towards their ability for pain self-management (Cooper et al. 2008). Patients' views of effective communication included being listened to and encouraged, feeling understood and understanding why they had the pain (May 2001). Health professionals were more concerned with whether a common goal could be achieved by establishing a mutual understanding of the treatment of the pain (Jeffrey & Foster 2012). Modes of communication discussed in the reviewed studies included face-to-face communication, written communication and telephone contact (Cooper et al. 2008, 2009). Patients felt most positively about face-to-face communication, as the language and non-verbal communication that health professionals used made them feel at the centre of care and involved in the process of their treatment. The feedback of written communication, however, was often negative when compared with face-to-face communication. For instance, patients rarely found helpful the books written by someone with a similar kind of pain which were given to them by the health professionals. Telephone contact was mainly considered as a form of follow-up and the perspectives on it were varied. Patients considered it helpful as a means of contact with their health professionals for advice on chronic back pain and acted as a helpline. Some patients also suggested that health professionals should proactively contact patients to provide motivation and reassurance about their conditions. But those who preferred direct access felt that telephone contact would only be useful when it led them to the health professionals in person (Cooper et al. 2009).

The experience of communication by both patients and health professionals highlighted the role of effective listening. It gave health professionals opportunities to understand patients' background and health needs when patients described their life situations, the feelings of pain and desired outcomes. Health professionals then could further offer specific treatment and self-management skills. For patients, effective listening was an approach to learn relevant strategies and co-operate with health professionals better to manage their pain. For patients with ‘passive’ attitudes towards pain self-management, effective listening was sometimes the motivation and encouragement to inspire them to take an active role. In addition, taking time and paying attention to listening was a way to present mutual respect between patients and health professionals, enabling a patient–professional partnership to be established.

Mutual understanding

All the studies emphasised participants' need to be understood. This included patients expecting health professionals to understand their pain and life situations and explain their diagnosis and teach self-management skills. In addition, it also included health professionals wanting their patients to understand their rationale for providing chronic back pain treatment. Mutual understanding enabled patients and health professionals to exchange their different types of expertise and knowledge in order to reach a common goal. Patients felt understood when they were listened to and believed, and when they were provided with options to participate, or not, in discussions and decisions about their treatment. The establishment of a mutual understanding was also considered central to building partnerships with patients from health professionals' perspectives. They believed their role was to educate patients about appropriate behaviour and help strengthen their confidence in their ability to manage the pain. In addition, a mutual understanding could facilitate the development and maintenance of trust between patients and health professionals. Some patients experienced relief when they found someone who they could trust, and described that being treated with trust made their rehabilitation process easier, as they felt able to turn to the professional with questions and phone them whenever there was a problem (Östlund et al. 2001).

Where misunderstandings arose concerning the experience of back pain and its management strategies, the partnership and chronic back pain self-management were affected to varying extents. Patients complained about their health professionals under- or over-prescribing pain medication because they felt that the nature of their pain had not been understood or assessed accurately by health professionals. For instance, ‘to get pain medicine is like fighting Muhammad Ali’, or in contrast, ‘they [health professionals] kept wanting to push more medicines, more medicines [when not necessary]’ (Matthias et al. 2010, p. 30). Furthermore, some patients complained that their health professionals did not take them seriously, as they had to describe their story several times to them. Patients further suggested that visiting the same professional would improve the continuity of the treatment, and enable professionals to gain a deeper understanding of them (Östlund et al. 2001). Health professionals' understandings of patients' pain and their life situations were improved during effective communication. This was confirmed by the patients, who further highlighted the importance of their communication and suggested that advanced communication skills were desirable for collaboration within patient–professional partnerships (Slade et al. 2009). Others felt that inappropriate self-management strategies suggested by the health professionals had led to misunderstanding in the partnership (Cooper et al. 2009, MacKichan et al. 2013). Being misunderstood was also experienced by health professionals, who sometimes felt their treatment advice conflicted with patients' views of their pain. They felt that these patients were seeking a ‘magic cure’ and did not understand the reality of what therapy could offer (Jeffrey & Foster 2012). Despite these difficulties, both patients and health professionals recognised that mutual understanding was closely linked with communication. Patients suggested that taking time over explanations and effective listening by health professionals would help them gain a better understanding of their conditions and expectations. On the other hand, health professionals felt that it was important for patients to appreciate the professionals' perspective on pain management so that they could work with each other in the long term. In particular, when working with or involving patients who held views in conflict with theirs, health professionals suggested that it was necessary to try to influence these patients' attitudes and seek to establish some common goals (Jeffrey & Foster 2012).

Roles of health professionals

Seven studies reported findings in relation to the role of health professionals (May 2001, 2007, Östlund et al. 2001, Cooper et al. 2008, Matthias et al. 2010, 2012, Jeffrey & Foster 2012). Patients described the role of the health professionals as being important in helping them find solutions to cope with their pain, holding them accountable for pain management and encouraging them and providing emotional support. These features of health professionals facilitated a strong partnership with patients, and were believed by patients to be integral to their ability to self-manage pain. Health professionals' (e.g. physiotherapists) manner of being friendly, empathic and sensitive to patients' needs, and their professional manner were valued by patients. Patients perceived that these characteristics reflected a collection of skills that health professionals possessed, including listening to the patients' concerns and understanding of their situation, giving information and seeking solutions for patients. Developing patients' self-management was also a target of health professionals, who considered their role to be to empower patients and help them build confidence to manage back pain (Jeffrey & Foster 2012, p. 271). However, the role of health professionals was not always commented on positively. Some patients complained about the manner of their health professionals and were very emotional about being treated as ‘a number but not an individual person’ (Cooper et al. 2008, p. 247). Even though health professionals might be described as being competent, sometimes patients were not satisfied with their treatment and how it was delivered, feeling that it was not patient-centred.

Information delivery

Six studies presented findings concerning the information that patients received about their back pain and proposed treatment from health professionals (May 2001, Cooper et al. 2008, Slade et al. 2009, Matthias et al. 2010, Jeffrey & Foster 2012, MacKichan et al. 2013). Patients expected to receive information about pain, including diagnosis and prognosis, treatment processes, self-management strategies, patients' roles and responsibilities for caring for themselves and managing their own pain. Even though all of this information did not make the pain better, patients described it as a good feeling to understand what was wrong in their bodies (May 2001).

Both patients and health professionals highlighted the importance of providing information and skills to help patients manage chronic back pain. In particular, explanations of the cause and prognosis of the pain and other functional problems were frequently identified as being useful. Health professionals also believed part of their role was to educate patients about appropriate behaviour to achieve self-management, for example, how to live with the pain and what to do to control it when it occurred. A good clear explanation was sought by both patients and health professionals by means of using lay language, drawing, charts and anatomical models and pamphlets. When a diagnosis presented rather abstract information to the public, a specific approach such as a model of the spine or their MRI picture was an easier way to convey the information to patients. Some forms of group activities organised by health professionals were also commented on by patients as being a useful method to address their health information needs, but they reported that it was largely due to the individual physiotherapists who led the groups (Cooper et al. 2008).

Patient involvement

Five studies reported on patients' involvement in their treatment, with a focus on the self-management of chronic back pain and decision-making (May 2001, 2007, Cooper et al. 2008, Slade et al. 2009, Jeffrey & Foster 2012). Involving patients has been driven at a policy level within the Department of Health in the UK (DH 2013), and identified as having an important impact on patient–professional partnerships (Cribb 2011). Most patients were positive about their experience of being involved in their treatment. Although they accepted that they had to live with the pain and no cure was available, they still showed a strong interest in being involved. Among these patients, some treated their involvement as a way to learn new skills to further manage the pain themselves. For example, ‘the act of looking for medical help was actually tied up with their idea of seeking greater self-management’ (May 2007, p. 131). Patients' involvement increased when the health professional applied their understanding of the patients' values, preferences and lifestyle to the development of individualised exercise programmes.

Being involved enabled patients with chronic back pain to share more of the responsibility to manage their pain. Providing information and resources enabled patients to feel more engaged with health professionals, and more informed to develop the suitable exercises that were appropriate for their life situations. Some patients were happy to agree with most decisions and follow the health professional's lead, while others preferred to make their own decisions on their treatment. Those who desired greater involvement in decision-making suggested that an individualised, communicative decision-making approach should be developed in partnership with health professionals. For example, ‘they [health professionals] didn't ask me what I thought I wanted, they just did what they assumed was physiotherapy’, ‘I don't know what other treatments I could have got’ (Cooper et al. 2008, p. 248).

Individualised care

Six of the studies emphasised patients' desire for individualised care (Östlund et al. 2001, Cooper et al. 2008, 2009, Slade et al. 2009, Jeffrey & Foster 2012, MacKichan et al. 2013). Individualised approaches were important for patients, and involved specific treatment for different health needs, personalised self-management strategies, regular communication, motivation and encouragement. Not only the treatment of chronic back pain but also the way in which it was delivered by health professionals was expected to be individualised (Cooper et al. 2008, 2009, Slade et al. 2009). Due to the nature of the pain, individualised care required a full clear understanding of patients' conditions as well as circumstances. Most comments arose from the appropriateness of self-management skills taught from health professionals. Some patients reported that their exercises were not sufficient, only focusing on one aspect of their lives such as lifestyle, while others felt the type of exercise they received was too easy or hard to complete, leading to poor motivation. Furthermore, patients felt that some self-management strategies recommended by health professionals were not achievable, for example attending a gym or exercise classes, due to time and financial constraints. They had to work out their own exercise programme such as cycling or walking. This reflected that a standard self-management plan might not be working for all. In Östlund et al.'s study (2001), patients were seeking a ‘professional mentor’, referring to a health professional who has the ability to offer individual care with a supportive treatment approach.

Healthcare service

Seven studies reported issues related to healthcare service, including its feasibility and availability (May 2001, Cooper et al. 2008, 2009, Slade et al. 2009, Matthias et al. 2010, 2012, MacKichan et al. 2013). Easy and quick access to health services, such as physiotherapy, with the availability of follow-up contact or review sessions were desired by most patients. However, having a large number of patients but limited consultation time restricted the availability of health professionals' support (Cooper et al. 2008, Slade et al. 2009). Patients were also concerned about the structure of the provision of healthcare services, suggesting that they should be able to decide when to return to their health professionals (e.g. physiotherapists). However, the fact is that open access or self-referral is not always the routine pathway into pain management services in the National Health Service (Mallett et al. 2014).

Discussion

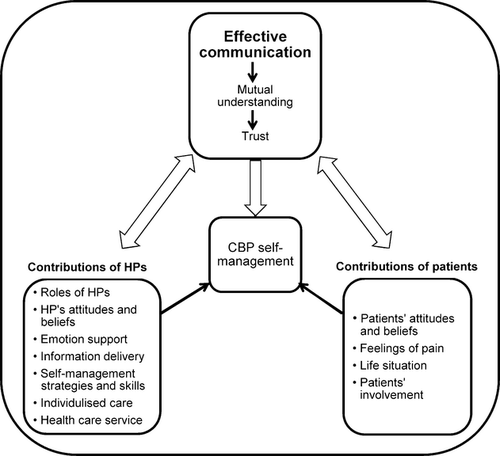

This review has drawn together the data from 10 qualitative studies, and explored a range of factors within the patient–professional partnerships that may influence the self-management of chronic back pain. Seven themes have been generated indicating how patient–professional partnerships influence self-management. How these may assist in building patients' self-management ability is discussed below. Figure 2 presents a model, based on the thematic synthesis of the results of the reviewed studies, that illustrates the likely influence of these partnerships on chronic back pain self-management.

In this model, effective communication is presented as a fundamental factor, helping to develop mutual understanding and trust. It connects the expert knowledge of health professionals with the patients' personal understandings and expertise of living with chronic back pain. In turn, effective communication serves to shape patients and health professionals' beliefs about and attitudes to chronic back pain management. Effective communication may produce mutual understanding and trust and greater co-operation between patients and health professionals. This can provide a solid basis for patients' self-management programmes. The individual contributions of health professionals and patients are necessary components of the self-management of chronic back pain. However, the impact of their contributions will be limited without effective communication due to a lack of mutual understanding. Effective communication integrates health professionals and patients' expertise and information, facilitating partnership development. Health professionals and patients may then share responsibilities and work collaboratively to address patients' health needs and achieve chronic back pain self-management.

Communication has been identified as core in this review; however, difficulties in effective communication still exist in reality, which may create tension between patients and health professionals. This has been echoed in the studies reviewed (Cooper et al. 2008, Jeffrey & Foster 2012), indicating that training that improves health professionals' communication skills as well as enhancing their partnerships with patients should be targeted (Jeffrey & Foster 2012). One purpose of effective communication is to provide explanations and educate patients. However, this needs to be a two-way communication process which enables the patient to contextualise the shared knowledge to their own reality so that they can then improve their ability to manage their pain. Effective communication is also limited by health professionals' personalities, behaviour, resources and whether or not they are willing to involve and motivate the patients in order to achieve a higher level of patients' satisfaction and centredness.

Among the different types of communication discussed in this review, face-to-face communication was the most popular with patients. However, this may be the least available type due to the restricted availability of health professionals. Telephone contact was recommended by some patients as a way of seeking advice or follow-up, which suggested that they would like some form of longer term relationship with their health professionals. Other resources are also available for health professionals to work with patients and to implement pain self-management in some parts of the UK. For instance, the Pain Toolkit, a selection of 12 tools, has been used in several pain clinics and administered by the healthcare team to guide patients in actively self-managing their back pain (The Pain Toolkit 2013).

Some patients in this review who accepted that their pain was a long-term condition with no cure expressed greater interest in being involved in the treatment process. This suggests that acceptance of the nature of chronic back pain may be the first step towards self-management and it might continuously inspire them to learn further. Patients also identified that it was important for health professionals to deliver personalised service and provide individualised self-management strategies. To achieve this, it may be necessary to spend time assessing the degree of the pain they are experiencing as well as their ability to self-manage the pain in advance. Having an accurate understanding of the nature and impact of the pain is a prerequisite to designing an individualised care package as it informs the decision-making process for choosing specific management strategies. Together with an understanding of patients' confidence and capability to undertake self-management, this will help establish evidence-informed individualised care. A number of questionnaires and scales have been designed and validated for this purpose. For example, the Partners In Health Scale, developed by Flinders University in Australia, was designed to assess patients' self-management ability for chronic conditions (The Flinders University 2013).

During this review, it emerged that a few patients preferred to maintain their old lifestyle rather than adopting self-management strategies, even though they were supported by their health professionals (MacKichan et al. 2013). Here, the theory of cognitive dissonance may be a possible explanation (Festinger 1962). That is, these patients understood that the taught self-management strategies could help with relieving the pain, but did not necessarily use them. According to this theory, dissonance is uncomfortable and therefore individuals are motivated to relieve it by changing either their beliefs or their behaviour in order to re-establish an equilibrium between the two. In such instances, it is the role of the health professional to assess the individual's readiness to change, using a framework such as the Transtheoretical Model of Change (Prochaska & DiClemente 1986). An accurate assessment of the patient's readiness to change will help inform the approach and range of interventions health professionals suggest to the patient to help them self-manage their pain. Where there is ambivalence, or motivation and self-belief is low, the use of motivational interviewing techniques may be helpful (Miller 1983). Motivational interviewing may also be helpful in exploring and resolving ambivalence. Unlike other behavioural change interventions, it focuses on motivational processes within the patient that support changes congruent with his/her own values and concerns, rather than being prescriptive (Miller 1983, Rollnick et al. 2008). In many instances, self-management of chronic back pain involves exercises and correcting posture. Such exercises and physical movements could be related to the issue of safety, as few patients considered that self-management was grounded in the lay domain, or was different from conventional medical care (MacKichan et al. 2013). Financial difficulties could be another barrier to the self-management of chronic back pain. For example, patients reported that they were unable to attend the recommended exercise classes due to money constraints (Cooper et al. 2009). For health professionals, it may be useful for them to explain why some physical exercises could help control the pain, as well as providing guidance on how these exercises may be practised safely. Information on free courses run by local community leisure centres may be useful for some.

Support not only from health professionals but also from family and friends may be needed for managing patients' emotion and stress (Snelgrove & Liossi 2013). It may be worth involving family members in general practice consultations, to teach and explain to both patients and their families about the pain and the strategies for self-management. A biopsychosocial model is also of importance in the field of chronic pain management, which considers illness as a complex interaction of biological, psychological and social factors that influences patients' reaction to the pain (Turk & Okifuji 2002, Gatchel et al. 2007). Self-management may also need some forms of peer support, as presented in Cooper et al. (2008), where patients can gain more information from others' experiences and may increase their self-efficacy (Parry & Watt-Watson 2010). A range of peer support services for people who are living with a chronic condition have been developed – notably, the UK's Expert Patients Programme, an approach to the management of chronic conditions that aims to support peer-led self-management training programmes (DH 2001). Peer support is often provided in a group setting facilitated by peers or health professionals. Patients tend to establish their relationships through having a similar background, health condition, religious belief, leisure interest or age. By talking to others, patients can share experiences related to their existing health problems as well as the actions taken to manage their conditions. Previous studies have reported that peer support is an essential component in helping patients manage stress and anxiety, as patients may feel less isolated or lonely (Mental Health Foundation 2012). However, gaining face-to-face peer support for chronic back pain could be challenging for patients whose pain has limited their physical functioning.

Some of the included studies involved patients with chronic pain in other areas of the body along with chronic back pain. Historically, chronic pain has been recognised as a non-specific symptom of a disease process, and both practice and research often draw their attention to the treatment or care underlying the pain. However, there is accumulating evidence to suggest that chronic pain can be regarded as a disease in its own right (Niv & Devor 2004, Siddall & Cousins 2004, Tracey & Bushnell 2009). Regardless of the locations of chronic pain, it can have a negative impact on quality of life, including disability, depression and physical changes. These will need patients to develop their self-management ability to cope with on a daily basis. Therefore, we included all these studies with the intention of examining patients' general pain self-management ability as a whole, rather than making suggestions on specific exercises or skills that are the most effective for patients with chronic pain in different sites.

Limitations of the review

Although the literature search was systematic and rigorous, some barriers were encountered to retrieving useful studies. First, this review was limited by the fact that only studies published in English were included. Grey literature was not included which may have introduced publication bias. However, grey studies tend to have an overall lower methodological quality and smaller effect than published literature (Egger et al. 2003, Hopewell et al. 2007). The search strategy was challenged by the absence of a search subject heading clearly delineating ‘patient–professional partnerships'. However, key words implying the same meaning were used to minimise this limitation. A few of the studies found were conference abstracts, on which the full study had not been published. Due to the lack of certain important methodological information, they were not suitable for inclusion. All the studies included were qualitative and involved small samples ranging from 11 to 34 participants, and not all of the studies were of high quality. The findings, therefore, are not necessarily transferable. However, some similar findings were reported by both low- and high-quality studies, which supported the decision made to not exclude studies of low quality. It may be worth considering the inclusion of studies published in non-English languages, grey literature and high-quality studies in future reviews, to overcome the above listed limitations.

Conclusion and implications for research and practice

The analysis and synthesis of findings in the studies reviewed suggests the notion that a partnership between patients and health professionals may support patients to self-manage their chronic back pain. Seven themes identified within patient–professional partnerships have the potential to influence patients' ability to self-manage their pain. Effective communication was highlighted as fundamental to the development of mutual understanding between patients and health professionals.

There are still other factors that may need to be taken into consideration when examining the influence of patient–professional partnerships on chronic back pain self-management ability. For instance, little is known about patients' age, gender, life stage and mental health. Therefore, there may be a need for further studies to look at the impact of these factors on patients' self-management ability. Given the fact that all the reviewed studies were qualitative, more research adopting quantitative and/or mixed methods may be needed for analysing whether any associations exist between patient–professional partnerships and patients' ability to self-manage chronic back pain. Of the ten studies, nine explored patients' experiences of living with chronic back pain, while only one examined health professionals' views on pain management. More research concerning health professionals or health service providers' perceptions would be useful.

For patients suffering from chronic back pain, accepting chronic pain itself, and seeking more information on their condition and self-management strategies to gain reassurance, may enable a better understanding of how to live with long-term pain. In practice, partnership in care may be of importance between patients and health professionals, with the benefit of establishing trust and addressing patients' health needs more specifically. Health professionals need to increase their awareness of the life circumstances of patients with chronic back pain and endeavour to make their service more individualised and flexible. This may also maximise the opportunity for health professionals to involve patients, and to enable the transformation from paternalism to partnerships in health services. At the same time, emotional support needs to be given as an essential part of health professionals' role to enable genuine sympathy with and respect for patients. To healthcare organisations, the provision of self-management support in the form of self-referral or telephone consultation may be considered to facilitate patients to self-manage their chronic conditions. It also would be beneficial to explore ways of guiding health professionals in developing and delivering individualised services to service users.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the School of Healthcare, the University of Leeds. All authors have no financial or personal relationships with other organisations or companies who might be interested. The authors have no conflicts of interest. We would like to thank Mark Clowes, Faculty Team Librarian in the School of Healthcare at the University of Leeds, for his help with the search strategy.