Are nurses well placed as care co-ordinators in primary care and what is needed to develop their role: a rapid review?

Abstract

Care co-ordination is reported to be an effective component of chronic disease (CD) management within primary care. While nurses often perform this role, it has not been reported if they or other disciplines are best placed to take on this role, and whether the discipline of the co-ordinator has any impact on clinical and health service outcomes. We conducted a rapid review of previous systematic reviews from 2006 to 2013 to answer these questions with a view to informing improvements in care co-ordination programmes. Eighteen systematic reviews from countries with developed health systems comparable to Australia were included. All but one included complex interventions and 12 of the 18 involved a range of multidisciplinary co-ordination strategies. This multi-strategy and multidisciplinarity made it difficult to isolate which were the most effective strategies and disciplines. Nurses required specific training for these roles, but performed co-ordination more often than any other discipline. There was, however, no evidence that discipline had a direct impact on clinical or service outcomes, although specific expertise gained through training and workforce organisational support for the co-ordinator was required. Hence, skill mix is an important consideration when employing care co-ordination, and a sustained consistent approach to workforce change is required if nurses are to be enabled to perform effective care co-ordination in CD management in primary care.

What is known about this topic

- Increasing health burden from chronic disease (CD) is driving changes to health systems.

- Care co-ordination is a common and effective component of models of CD management.

- Within primary care, the work roles of nurses and general practitioners have altered through the implementation of programmes to managing CD.

What this paper adds

- Nurses are most often the care co-ordinators and require specific training for this, as well as organisational changes to the way that primary care practices function.

- While care co-ordination is effective, there is not yet evidence about whether the discipline of the care co-ordinator makes any difference and this is an area of needed research.

Introduction

Chronic disease (CD) is increasing the healthcare burden and healthcare cost in developed nations across Europe, United States, United Kingdom and Australia (Greb et al. 2009, Aspin et al. 2010, Cant & Foster 2011, Ehrlich et al. 2011, Friedman et al. 2014). Most CD in developed countries is managed through primary care (Britt et al. 2012, Friedman et al. 2014, Fuller et al. 2014) with the challenge being how best to organise this workforce to meet the needs of a complex and diverse clientele (Friedman et al. 2014).

In Europe, new models of primary care tend to be based on a chronic care framework and aim to improve self-management, provide decision support to clinicians, change the delivery design through better links between healthcare services and community resources, and improve management and co-ordination (Greb et al. 2009). Similarly, expectations placed on primary care management of CD within the United States have grown over the last 20 years (Friedman et al. 2014) with a tendency for these to be disease specific and neglectful of the complexities of the management of co-morbidities (Greb et al. 2009).

Other innovations in primary care have included the incorporation of mental and behavioural health management with that of physical health, and an emphasis on redesigning practice including the functions of existing personnel (Friedman et al. 2014). New models such as the Patient-Centred Medical Home are designed to deliver the core functions of primary care and provide patient-centred and co-ordinated care, while improving access, quality and safety (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2014). The UK Government's Mandate for NHS England (UK Department of Health 2013) requires the National Health Service to better support people with ongoing health problems through patient and carer involvement. Individuals are empowered to make their own decisions about care through a personalised care plan that reflects their preferences and agreed decisions. The ‘House of Care’ is a metaphor now used in the United Kingdom which aims to guide those working in primary care to adapt the chronic care model to their own situation (Coulter et al. 2013).

The evidence around CD management has resulted in Australian policy that supports early intervention, screening and monitoring to identify people at risk of disease, and targeted, appropriate care for those people living with CD (National Health Priority Action Council 2005). Interdisciplinary team-based approaches that are co-ordinated across sectors of the health system have been identified as a method to enhance effective management of CD (Aspin et al. 2010). Co-ordination of care (with inter-sectoral collaboration and facilitation of access) has been shown to result in patient-centred care, and there is also evidence that care co-ordination benefits both processes of patient care and patient outcomes (Davis 2005, McDonald et al. 2007). Co-ordinating care for patients with multiple service needs in Australia is however hampered by mixed and complex arrangements between funding, policy and service delivery (Battersby 2005, Aspin et al. 2010).

Background and objectives

Review of the roles and skill mix of personnel in primary care is one aspect of CD management that has gained momentum. Within the United Kingdom, extensions to the roles of nurses into domains that were traditionally undertaken by general practitioners (GPs) have occurred around the management of asthma, diabetes and heart disease (Sibbald et al. 2006). Nurse led care in the United Kingdom is now common with some practice nurses and all nurse practitioners able to prescribe, freeing up GP time to concentrate on the patients with the most complex medical needs (Hoare et al. 2011).

Through various government-funded incentive programmes, Australian GPs are able to take responsibility for monitoring the long-term health status of their patients and for some co-ordination between primary and secondary healthcare, allied health and community-based services (Ehrlich et al. 2011). Inherent in recent policy and funding initiatives has been a steady reorganisation of the general practice workforce and enhanced capacity through increased collaboration between GPs, allied health professionals and nurses (Cant & Foster 2011). Registered nurses who work in general practice (practice nurses) are ideally placed to assist with care co-ordination (Ehrlich et al. 2011) or undertake care navigation roles (Manderson et al. 2012), and emerging evidence indicates that there are specific areas of CD care in which nurses are integral and also effective (Sibbald et al. 2006, Carey & Courtenay 2007, Ekers et al. 2013).

- Who usually co-ordinates CD care in primary care and what roles do they perform?

- Is there any variability in patient outcomes depending on who provides the care co-ordination role?

Care co-ordination is the deliberate organisation of patient care activities between two or more providers, individuals or organisations (Øvretveit 2011) with the aim of facilitating the appropriate delivery of healthcare service, to reduce segmentation and fragmentation of services and ensure timely access (Greb et al. 2009). Care co-ordination is a process that links people with special healthcare needs, and their families to services and resources in a co-ordinated effort to maximise the potential of the client and provide optimal healthcare. Care co-ordination is often managed by the exchange of information among participants responsible for different aspects of care. (McDonald et al. 2007)

Method

We conducted a limited database search consistent with accepted methodology for a rapid review (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools 2014). Given the volume of research in CD management, we restricted the search to systematic reviews only and used the following criteria to guide our search and assist with the inclusion process.

- Had a specific focus on ‘care co-ordination’, or alternatively included other models of care (that described tasks or components) that contribute to the organisation of patient care including shared, collaborative or integrated arrangements.

- Provided documentary evidence that an organised method in the systematic review was used to locate, assemble and evaluate literature according to specified criteria.

- Used quantitative measures to assess effectiveness (clinical or service outcomes) or provide a narrative synthesis of the included studies.

- Included an adult population (18 years and over) with a diagnosis of one or more CDs classified by the Australian National Public Health Partnership (2001) – ischaemic heart disease; stroke; lung cancer; colorectal cancer; depression; type 2 diabetes; arthritis; osteoporosis; asthma; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); chronic kidney disease; and oral disease.

- Were conducted in general practice or similar primary care setting with an intervention carried out by staff employed at that setting or between a primary care service and another health or community service. We used the Australian Medical Association (AMA) definition of primary care:

…a service providing curative treatment given by a first contact provider along with promotional, preventive and rehabilitative services provided by multidisciplinary teams of healthcare professionals working collaboratively

(Australian Medical Association (AMA 2010) - Were available in full text, English and includes primary studies conducted in comparable health systems to Australia such as Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States and the Netherlands.

A comprehensive search strategy was applied to Medline and All Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) Reviews (Appendix 1 in the Supporting Information). These databases were chosen because they are more likely to hold evidence-based literature and support a search filter to identify citations that have used this methodology. The years 2006–2013 were chosen as this coincides with relevant re-direction of policy and funding for primary care in Australia. This includes the introduction of payments through the national health insurance programme (Medicare) to support primary care services such as health assessments, nurse practitioners and CD management, some of which are designed to improve co-ordination and multidisciplinary care for people with complex care needs. It also includes the development of the National Chronic Disease Strategy and the National Service Improvement Frameworks aimed at increasing consistency and co-ordination of care in Australia (Aspin et al. 2010). We also searched the Cochrane Library and the ‘Roadmap Of Australian primary health care Research’ (ROAR) database http://www.phcris.org.au/roar/index.php. Hand-searching was limited to the reference lists of seminal reviews and to identify primary publications.

Decisions to include studies were made at two stages: an initial assessment based on the broad inclusion criteria listed above and a second assessment based on the contribution of the review to our research questions. We wanted to identify citations in which there was an examination of the active components of care co-ordination, particularly related to CD management, any impact on patient outcomes and/or the role of various health workers in care co-ordination.

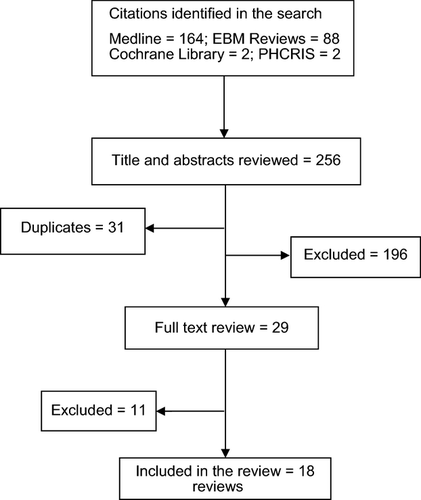

In total, 256 citations were identified by the search (Figure 1). Both authors assessed titles and abstracts. Full-text review was conducted on 29 citations with a further 11 being excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

A data extraction template was developed to document the following information from the systematic reviews: author; year of publication; health conditions; population group; description of the intervention (co-ordinated care, case management, integrated care, etc.) and the major outcomes; and professionals involved, specific training provided to these individuals and their roles and responsibilities. A summary of this information has been provided in Appendix 2 and 3 (Supporting Information). One author (S.P.) completed the initial extraction of the data and a second author (J.F.) reviewed the extraction. Discussion was held over missing data and lack of clarity in the publication and where any disagreement about content occurred. This data extraction summary was used to compile a narrative overview from the systematic reviews according to the two research questions.

The AMSTAR checklist was used to assess each of the systematic reviews for methodological quality (Table 1). This validated appraisal tool consists of 11 items covering the design, study selection and data extraction, literature search, quality assessment, reporting and analysis, bias and conflict of interest (Shea et al. 2007). AMSTAR can be used to assess the quality of systematic reviews incorporating both randomised and non-randomised studies (Pieper et al. 2014). Reviews were not excluded based on this assessment, but quality was considered in relation to question 2, which was concerned with the effect of care co-ordination interventions on patient outcomes.

| Author/date | AMSTAR score | Comments about scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Baishnab et al. (2012) | 11/11 | High quality |

| Bower et al. (2006) | 3/11 | No a priori design stated; duplicate study selection and data extraction not stated; no search for grey literature; no table of excluded studies; no quality assessment of included studies; analysis not controlled for quality criteria; no assessment of publication bias; conflict of interest statement but no funding statement |

| Buckley et al. (2010) | 11/11 | High quality |

| Carter et al. (2009) | 1/11 | No a priori design stated; search limited to one database; no grey literature; no list of included and excluded studies; no characteristics of included studies; no quality assessment or analysis by quality; publication bias not assessed and no conflict of interest statement |

| Chin et al. (2011) | 2/11 | No a priori design stated; duplicate study selection and data extraction not stated; no search for grey literature; no table of excluded studies; no quality assessment of included studies although states acceptable quality; analysis not controlled for quality criteria; no assessment of publication bias; no conflict of interest statement |

| Christensen et al. (2008) | 8/11 | No a priori design stated; no table of excluded studies; unsure about the appropriateness of the methods used to combine the results |

| Cranston (2006) | 5/11 | No a priori design stated; two people did not extract data; no table of excluded studies; unsure about the appropriateness of quality assessment in analysis; no assessment of publication bias and no conflict of interest statement provided |

| Crocker et al. (2013) | 7/11 | No grey literature; no tables of studies excluded; no quality assessment; tabular methods of combination only used |

| Glynn et al. (2010a,b) | 11/11 | High quality |

| McDonald et al. (2007) | 6/11 | No a priori design stated; single reviewer did study selection and data extraction; unsure about the use of quality assessment in analysis; no assessment of publication bias |

| Manderson et al. (2012) | 4/11 | No a priori design stated; no grey literature search; no search for grey literature; no table of excluded studies; no quality assessment or analysis based on this; unsure about the appropriateness of the analysis; publication bias not assessed |

| Mitchell et al. (2008) | 6/11 | No a priori design stated; no list of excluded studies; no analysis by quality; publication bias not assessed |

| Øvretveit (2011) | 2/11 | No a priori design stated; unsure about how data extraction was done; no list of studies provided; no quality assessment used; unsure about method of synthesis; no statement about publication bias or conflict of interest |

| Powell Davies et al. (2008) | 9/11 | No a priori design stated; publication bias not dealt with |

| Smith et al. (2007) | 10/11 | Publication bias not assessed |

| Smith et al. (2013) | 10/11 | Publication bias not assessed |

| Tieman et al. (2006) | 3/11 | Unsure about a priori design stated; duplicate assessment and data extraction; no table of include/excluded studies; unsure about relevance of analysis |

| Williams et al. (2007) | 8/11 | No a priori design stated; no table of excluded studies; no discussion of publication bias |

Results

Overview of the reviews identified

We included 18 systematic reviews, three with a specific focus on care co-ordination (McDonald et al. 2007, Powell Davies et al. 2008, Øvretveit 2011). Care co-ordination is however not a discretely defined activity. There are a number of terms which are used synonymously or in conjunction with care co-ordination including collaborative care, continuity of care, disease management, case management, care management and care navigation. The remaining reviews used a variety of these terms to describe their interventions, but all implied an activity designed to aid better co-ordination and management, and improve or measure any impact on patient care or patient care processes.

All reviews took place in a primary care setting, although not exclusively in general practice. Some reviews did not distinguish between care provided in general practice and care provided in a community health or outpatient/outreach setting (including and involving health professionals employed by community agencies or hospital-based employees). Some used condition-specific clinics (e.g. asthma/respiratory) operated by primary care staff, whereas reviews with a focus on mental health/depression tended to operate as extensions or enhancements to primary care, such as the specialist conducting clinics at the general practice or linking with a specialist or allied health multidisciplinary team. Reviews covered a range of CDs including mental health and multi-morbidity.

All except one (Crocker et al. 2013) assessed complex (more than one component) interventions. Complex interventions incorporated a variety of strategies and were frequently implemented as mixed rather than single strategies. Predominantly, reviews sought to assess effectiveness, and strategies were aimed at the provider level or at the system or organisation of care. Intervention components tended to be aligned with common chronic care models including case management, patient self-management, structured methods for patient monitoring and follow-up, audit and feedback, provider education and training, information systems to access and manage patient data (including recall and decision support tools), and clinical guidelines or protocols to guide clinical management.

Reviews were of mixed quality according to the 11-item AMSTAR rating ranging from high to poor (median score 7). This might to some extent reflect the timeframe since publication and changes in requirements by journals and other bodies for better and more consistent reporting against validated instruments.

Who usually co-ordinates chronic disease care in primary care and what roles do they perform?

Although it was possible to discern the disciplines involved in care co-ordination in 15 of 18 reviews, the discussion as to the specific discipline input was limited. Care co-ordination activities were most often multidisciplinary (12 of 18 reviews) involving GPs, specialists, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, dieticians and occupational or other allied health therapists. Pharmacists were valuable components of interventions particularly those relying on the recording or monitoring of medications such as antihypertensives, lipid lowering or glycaemic control (Carter et al. 2009, Buckley et al. 2010), but many other disciplines contributed to the interventions included in the systematic reviews we considered. It is possible that this reflects the CD environment in which individuals present with complex care needs, necessitating more input by professionals and more relationships between those individuals (McDonald et al. 2007).

In three reviews, care co-ordination was conducted solely by a nurse (Baishnab & Karner 2012, Manderson et al. 2012, Crocker et al. 2013), and actual roles were described in two of these. Nurses in Crocker et al. (2013) took on case management roles in which they assessed need, provided medication review and followed up appointments. Manderson et al. (2012) reviewed care navigators, where nurses with advanced training conducted home visits, liaised with medical and community services and caregivers, provided education and brokered services for patients with a range of CDs.

The roles undertaken by nurses in the reviews where multidisciplinary teams were prominent varied in their description. These were care management, which included tracking and monitoring of patients with depression (Christensen et al. 2008), case management for patients with hypertension where nurses or pharmacists took on ‘activities distinct from their traditional roles’ (Carter et al. 2009), and case management and co-ordination of care with nurses and ‘guided care nurses’ undertaking the role, which was otherwise not described (Tieman et al. 2006, Smith et al. 2013). Buckley et al. (2010) identified a range of disciplines involved in care co-ordination activities including nurses, doctors and pharmacists, and noted that both nurses and pharmacists were ‘proactive’ in care management. Nurses participated as either principle clinician or co-ordinator, including a nurse-led clinic for ischaemic heart disease in ‘partnership’ with doctors. A model of co-ordinated multidisciplinary care was discussed in the review by Mitchell et al. (2008), where the care co-ordinators were usually nurses based in specialist units, and working in the community with allied personnel based in the same unit, or with local primary care providers. Smith et al. (2013) also reported that in six of nine included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), it was the nurse's role (usually a nurse specialist) to co-ordinate patient care across the primary and specialist care sectors.

Cranston (2006) reviewed the role of practice nurses involved in nurse-led respiratory clinics where they were responsible for counselling, education, preparing asthma management plans and performing spirometry. This narrative review reported that while nurses were actively engaged in care co-ordination activities, focus group data from 54 GPs considered that it was the GP who held the role of primary care co-ordinator and patient advocate; and that the role of the nurse was one of an ‘assistant’, or an additional resource, and not a substitute for the care provided by the GP. Those practice nurses without advanced asthma qualifications felt ill-equipped to take on the role of providing respiratory care, and were not confident with the expectations placed on them to perform in these roles.

The results of these reviews provide limited information on which to draw conclusions around this question. Hence, while we cannot determine who is best to provide co-ordination in primary care, we can conclude that nurses tend to perform this role more so than any other discipline. We can also conclude that the skills required for care co-ordinator roles should be a consideration and advanced training is likely required for this role.

Is there any variability in patient outcomes depending on who provides the care co-ordination role?

The included reviews provide only limited evidence to differentiate outcomes according to who co-ordinates care. Most trials involved co-ordination across multidisciplinary teams with outcomes from care co-ordination inconsistently reported.

In the review by Powell Davies et al. (2008), at least half of the studies that measured health outcomes reported statistically significant positive results. Reviews that included mental health problems generally reported positive outcomes relating to antidepressant use and medication adherence (Bower et al. 2006, Gilbody et al. 2006, Øvretveit 2011), depression outcomes (Bower et al. 2006, Christensen et al. 2008), functional and social outcomes and patient satisfaction (Williams et al. 2007). These reviews were of varying quality. The meta-analysis conducted by Smith et al. (2013) of shared care requiring co-ordination across a range of conditions found no statistically significant benefits across studies for physical health outcomes, overall mental health outcomes or psychosocial outcomes including measures of disability and functioning, but with improvements for mental health recovery and maintaining remission.

The support for care co-ordination on physical health outcomes was less consistent and as with the mental health outcomes, these results came from reviews of mixed quality. Positive outcomes were found for blood pressure (Carter et al. 2009) and glycaemic control (Øvretveit 2011). Positive outcomes were also found for cholesterol control, but this did not extend to blood pressure, smoking status or body mass index for patients with ischaemic heart disease (Buckley et al. 2010). Cranston (2006) reported no effect on asthma morbidity, lung function, medication use, quality of life or smoking cessation for patients with asthma or COPD. Tieman et al. (2006) also reported mixed results relating to COPD. Smith et al. (2013) found no evidence of improved health outcomes for people with multi-morbid CD, but some benefits were shown in 3 of 10 studies that reported outcomes relating to prescribing and medication use. Some positive health outcomes were reported on the management of congestive cardiac failure and stroke (Øvretveit 2011), while Mitchell et al. (2008) reported no impact on mortality and inconclusive evidence on functional outcomes for people with stroke.

In relation to service use, we found some reports of positive outcomes relating to co-ordination. These tended to be in the form of increased referrals (Cranston 2006), decreased hospital admission rates and length of stay (McDonald et al. 2007, Øvretveit 2011) and improved contact and attendance at primary care follow-up (Glynn et al. 2010a, Crocker et al. 2013). However, Smith et al. (2013) found no improvement in hospital admission rates for a multi-morbid population, but found improved prescribing and risk factor management indicating a potential to reduce health service costs in the long term. Hence, health service utilisation outcomes were also mixed.

In systematic reviews of complex interventions, it is difficult to establish the active or successful ingredients of an effective strategy (Fuller et al. 2011). This rapid review has been unable to provide any definitive information linking positive outcomes with the particular person or discipline that provided the care co-ordination, although some did recommend this as an aspect worthy of further study. Glynn et al. (2010a) found mainly favourable results for nurse- and pharmacist-led care in the management of patients with hypertension, and Tieman et al. (2006) found that case management by a pharmacist was associated with better glycaemic control. Cranston (2006) found no clear benefit related to nurse-run clinics compared to usual care in altering asthma or COPD outcomes, and Mitchell et al. (2008) concluded that it was uncertain if active multidisciplinary engagement of GPs or other primary care professionals involved in care planning contributed to these outcomes. Despite reports of some positive effects on outcomes, one of the higher quality reviews (Buckley et al. 2010) which assessed service organisation interventions for secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease, stated there was insufficient evidence to suggest that the effectiveness of interventions is affected by the type of primary care professional who leads the intervention. This may be less the case when treating depression however, as provider type (nurse and pharmacist) showed a trend to significance in the review by Christensen et al. (2008), where case management was more positively associated with patient outcomes when monitoring, and delivery of treatment was done by a health professional with a mental health background or by practice nurses rather than pharmacists.

In the review by Glynn et al. (2010a,b), it was suggested that further evaluation from large RCTs on the possible effect of the provider is warranted and Crocker et al. (2013) proposed that determining who among the primary care team is most effective could have significant workflow and financial implications for the implementation of discharge telephone follow-up.

Discussion

A number of disciplines participate in care co-ordination in primary care. Nurses are frequent and active participants in CD care co-ordination and engage in a range of tasks including patient education, patient monitoring and tracking, clinical assessment and follow-up, case management and care planning. Despite conducting a variety of tasks, our rapid review found no consensus or definitive list of the co-ordinating tasks that nurses or other disciplines should perform, and no standard model was identified for nurse care co-ordination. The Kings Fund in the United Kingdom does suggest, however, that care co-ordination needs to include one co-ordinator who can be identified and whose key functions are to provide continuity, manage referrals, advocate, communicate across care providers and take accountability (Coulter et al. 2013, Goodwin et al. 2013). The involvement of nurses in the reviews that we examined ranged from low-intensity clinical support activities to nurse-led activities, where the nurse worked as the principle clinician, including the operation of specialised clinics.

The systematic reviews that we studied ranged in quality and included multiple strategies that were implemented with a degree of purposeful co-ordination. The more direct activities included patient assessment, care planning, case management, enhanced communication for patients and providers, monitoring and adjusting clinical patient care and evaluating health outcomes. In addition, the involvement of the patient or carer as central in care planning and monitoring processes was an important component of the model of care co-ordination. Indirectly, these activities were further supported by electronic medical records, decision support tools to guide clinical care, promotion of clinician education and skills, and routine reporting and feedback.

In terms of outcomes related to the discipline of the co-ordinator, while we found positive clinical outcomes reported in some reviews, these were inconsistent across disease classifications. The implementation of multi-component strategies was more common and there is some evidence to suggest that these complex strategies perform better than a simple discrete strategy. Added complexity, however, means that it is difficult to isolate the components that make any model effective, and this extends to the effect of different disciplines on care co-ordination.

The reviews we included covered a range of disciplines involved in the co-ordination of patient care including nurses, GPs, psychologists, pharmacists and social workers. Overall, the tasks and roles pertaining to each discipline were not explored in depth and we found no conclusive evidence about outcomes related to the discipline of the care co-ordinator. Tieman et al. (2006) has suggested that the more disciplines involved in the strategy the better the outcome. As the impact of specific roles on patient outcomes could not be determined, further research that could tease out discernible effects would be of value.

We identified a range of specific co-ordination roles in which additional training was provided to support that role. Models such as nurse-led clinics, guided care and care navigation require the nurse to have specialist training and this is also the case in other advanced nursing roles where nurses substitute for, or complement GPs in CD management. Having professionals with suitable knowledge, skills and level of expertise and the support of expert supervision were found to be important to the success of care co-ordination (Bower et al. 2006). Nurses without advanced qualifications or additional training felt ill-equipped for specialist type roles (Cranston 2006). It is possible that the variability in the outcomes related to care co-ordination might in part be attributed to the variation in the skills and knowledge of individual care co-ordinators employed in various roles across the studies.

Through this rapid review, we have established that nurses are a well-placed healthcare discipline to take on the care co-ordination role for people with CD. The range of co-ordination tasks are well described as is the need for flexibility in the use of the care co-ordination system. While it is clear that developmental opportunities need to be provided to individual staff to take on care co-ordination, so that they can build their knowledge and skills through training, this will not be sufficient. This rapid review has found that systems of support are also needed that include organisational change in primary care practices such as information systems, monitoring and recall processes, guidelines and multidisciplinary team arrangements. These are required to change primary care practice so that co-ordinated care becomes more routine (Ehrlich et al. 2013, Fuller et al. 2014). Other studies have reported that the care co-ordinator needs to have responsibility and the power to exert influence in the primary care setting and without this care co-ordinators have reported feeling ineffective and isolated (Goodwin et al. 2013, Fuller et al. 2014). Many Australian nurses working in primary care continue to experience difficulties in collaborating with their GP employers to develop a care co-ordination role that enables the nurse to work to their full scope of practice (Ehrlich et al. 2013, Halcomb et al. 2014).

In the Australian setting, organisational changes to primary care practices are made difficult with the wide variations in workforce arrangements that are essentially small private businesses. Care co-ordinators need to have a role that is agreed upon and resourced appropriately, with authority in the work setting in which the co-ordinator is employed. While there are now programmes in Australia that support both nurses and also primary care practices for this role, these programmes need a clear and stable direction and resourcing. This is required over the long period that will be required to change primary care in Australia towards systematic team-based models for effective co-ordination of CD management.

This review has some limitations. First, although we utilised a comprehensive search strategy, we limited our search to systematic reviews from two databases and hence our reach could have been more thorough. Given the ambiguity around the term, we tried to include a range of search terms that would also capture the components of care co-ordination, but as there are a number of ways to view the concept, it is also possible that some work has been missed. Identifying reviews that used terms such as ‘shared’ and ‘collaborative’ care relied largely on the judgement of the authors to determine that ‘care co-ordination’ was an active component of these models. However, as two authors reviewed the material, we feel confident that within these models, a significant level of care co-ordination took place. We used predefined criteria for the search for relevant material and for the inclusion/exclusion criterion which was a pragmatic approach, but the lack of other sorts of material may have introduced some publication bias. Although we provide some assessment of quality, the limited amount of information provided relevant to our questions has precluded us from synthesising just the better quality systematic reviews. Also, the scoring achieved by some systematic reviews may reflect a diversity in their approach/aims or the time of their publication, as changes in requirements by journals and other bodies for better and more consistent reporting against validated instruments have occurred more recently.

While narrative reviews can be seen as a limited and less objective way to view the evidence, they are a valuable way of drawing together the contextual elements around questions such as ours. Both authors are affiliated with the discipline of nursing and as such we had a special interest in teasing out information relating to nursing roles in primary care. We feel this review has highlighted some areas for future research to assess the potential impact of nursing roles in this setting in the light of changing health environments. The review has also added valuable information about the support and training required for care co-ordination roles.

Acknowledgements

The Adelaide North East Division of General Practice funded part of this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.