Interobserver reproducibility of a hybrid three-tier grading system of papillary nonmuscle invasive urothelial carcinoma: an international Uropathology study

Abstract

Aims

A hybrid-three tier system with low grade (LG), high grade- G2 (HG-G2), high grade- G3 (HG-G3) has been proposed in recognition of, and to help address, the clinical heterogeneity within high grade WHO 2004/2022. We assessed interobserver reproducibility amongst international uropathologists using this three-tier approach.

Methods and Results

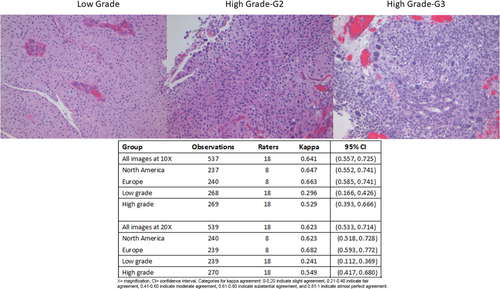

Papillary Ta nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) specimens (n = 30) were selected and graded by two uropathologists and assessed using WHO 2004/2022 and WHO 1973 and categorized as LG (n = 15), HG-G2 (n = 8), HG-G3 (n = 7), and photographed at 10× and 20× magnification. Images were circulated via Survey Monkey to invited uropathologists who determined: (1) that image was LG or HG, and (2) if HG, assigned to G2 or G3. Model-based kappa measure of association was used to assess interrater agreement. Eighteen uropathologists:(eight North American, eight European, two other) assessed 60 images with 1076 gradings for analysis. The kappa value amongst Europeans versus North Americans was 0.663 versus 0.647 for 10× images and 0.682 versus 0.623 for 20× images. At 10×, agreement for LG, HG-G2, and HG-G3 was 74.6%, 63.6%, and 92.0%, and at 20× was 64.3%, 63.9%, and 95.2% respectively.

Conclusion

Three-tier grading of papillary Ta NMIBC had substantial interobserver agreement amongst international uropathologists. The recognition of the HG-G3 case reached the highest concordance. North American uropathologists had comparable kappa scores (substantial agreement) to Europeans, despite being unaccustomed to separating HG cases into G2 and G3, demonstrating three-tier grading could be “quickly” adopted by genitourinary experts if endorsed and required by the relevant bodies in their jurisdiction of practice.

Graphical Abstract

Abbreviations

-

- AUA

-

- American Urological Association

-

- CIS

-

- carcinoma in situ

-

- EAU

-

- European Association of Urology

-

- H&E

-

- haemotoxylin and eosin

-

- HG

-

- high grade

-

- ISUP

-

- International Society of Urological Pathology

-

- LG

-

- low grade

-

- LIS

-

- laboratory information systems

-

- NMIBC

-

- nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer

-

- PUNLMP

-

- papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential

-

- WHO

-

- World Health Organization

Introduction

Globally, bladder cancer is recognized as the tenth most common malignancy and sixth most frequent in men, with approximately three-quarters of patients having nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) at initial presentation.1 The term NMIBC encompasses three distinct pathologic entities, namely, carcinoma in situ (CIS, Tis), papillary noninvasive carcinoma (Ta disease), and carcinoma (papillary and nonpapillary) with invasion limited to the lamina propria (T1 disease). Grading of papillary NMIBC is useful in determining a patient's risk of progression2, 3 and is a key prognostic variable that is incorporated into various risk stratification tools.4, 5

There are two World Health Organization (WHO) grading schemes that are widely used for papillary NMIBC: the original two-tier WHO 2004 system (now known as WHO 2004/2022)6 and the three-tier WHO 1973 system.7 The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines recommend grading with both WHO 2004/2022 and WHO 1973,5 while the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines use the WHO 2004/2022 grading alone.4 Two published studies have shown that utilizing a hybrid three-tier grading system2, 3 is a better prognosticator for determining progression to muscle invasion and beyond (≥T2).

There are limited original studies assessing interobserver reproducibility in assigning grade to papillary NMIBC8 and the published studies have been variable in terms of design, types of cases assessed, and number of cases included. The interobserver reproducibility assessed by kappa statistics is slightly higher for WHO 2004/2022 than WHO 1973 and improves when the category of papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) is excluded from analysis. Nevertheless, reproducibility is at best moderate, irrespective of grading scheme.8 Intraobserver reproducibility is similar for both WHO 1973 and WHO 2004/2022.

In September 2022, a consensus meeting on bladder pathology was organized by the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) in Basel, Switzerland, which was informed by premeeting surveys of the ISUP membership and the EAU membership.9 Working group 1 reviewed bladder cancer grading system performance, and based on the premeeting surveys of both memberships and the in-conference voting, there was a preference to refine grading of papillary NMIBC into a three-tier system.8, 10 As such, the existing category of “low grade” (LG) in WHO 2004/2022 would be retained and the “high grade” (HG) WHO 2004/2022 would be divided into high grade- grade 2 (HG-G2) and high grade- grade 3 (HG-G3) in line with the WHO 1973 system.

The main purpose of this current study was to explore the interobserver reproducibility of such a three-tier hybrid grading scheme amongst a group of international uropathologists. A secondary aim was to determine whether the magnification, either 10× or 20×, used in grading cases had an impact on the grade assigned.

Methods

The laboratory information systems (LIS) of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and University Health Network, two academic institutions in Toronto, Canada, were searched for papillary, NMIBC diagnosed at biopsy or transurethral resection between the years 2003–2022. Research Ethics Board approval was granted at both centres; REB 187-2016 and CAPCR 20-5817, respectively.

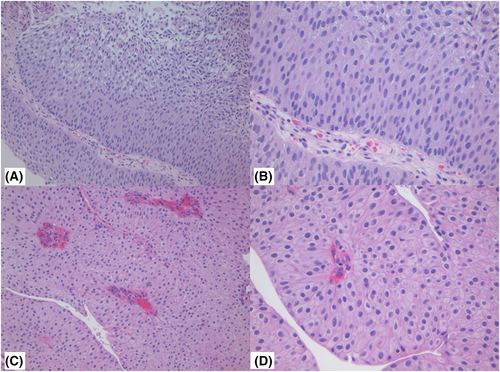

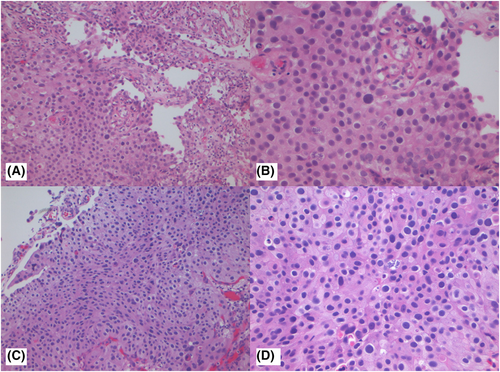

The criteria for inclusion were: papillary carcinoma, staging category Ta (noninvasive) with minimal cautery artefact and variability in haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Each case was reviewed in a consensus manner by two uropathologists (M.R.D., Tv.D.K.) working cooperatively to determine cases to be selected for study inclusion. The cases were selected to represent a spectrum of diagnostic difficulties from those that were deemed straightforward to others that were more challenging. Each case was assessed using two grading schemes: WHO 2004/2022 (cases designated as LG, HG), and a hybrid three-tier grading scheme (cases designated as LG, HG-G2, or HG-G3). For each case, a representative area was annotated and then photographed at 10× and 20× magnification using an Olympus BX53 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with mounted Leica DFC320 camera (Wetzlar, Germany). The areas that were selected for image capture had to be free of cautery artefact, have reasonable quality H&E, with good nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, and minimal histologic artefacts. Each selected area of image capture was felt to be representative of the overall grade assigned at prior case sign out.

Each image was assigned a random number from 1 to 60 and imported as JPEG images into Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com, California, USA) to create 60 unique survey questions. For each image, there were two questions: 1- is the carcinoma HG or LG using WHO 2004/2022, and 2- if HG is it a HG-G2 or a HG-G3?

Eighteen international uropathologists with expertise in bladder pathology, (FA, YA, MBA, LC, SD, ME, AH, AL-B, SM, MLvM, JO, GPP, HS, JW, SRW, SEW, and one North American pathologist who requested to remain anonymous) were invited to participate in the study. They were provided with the following instructions: “Images are a mix of 10× and 20× objective magnification.” (Participants were not informed that the same cases were photographed at both 10× and 20×.) The cases had been collected from different institutions, and therefore they should expect some variability in H&E staining. When assessing the HG cases, (they were instructed) to use the criteria of HG-G3 being a carcinoma at the far end of the grading spectrum, based on disorder, marked variation in nuclear size, irregular nuclear contours, severity of nuclear atypia, nuclear hyperchromasia, and mitotic activity (Table 1). Each individual survey also included three general questions at the start of the survey, which were: 1- location of practice (North America, Europe, or other), 2- what grading system they used in daily practice for papillary NMIBC (WHO 2004/2022, WHO 1973 or other), and 3- what magnification they preferred for grading (10×, 20×, both or other). The survey remained open for 2 weeks. The responses were downloaded into excel file format.

| Grading scheme | Architectural and cytological features |

|---|---|

| WHO 2004 | |

| Low grade | Delicate papillae, orderly cohesive cells with enlarged oval nuclei showing some variability in nuclear size/shape. Infrequent, basal mitoses. |

| High grade | Complex papillae with fusion and branching showing disordered, crowded cells with loss of polarity. Nuclear pleomorphism with prominent nucleoli and frequent, multi-level mitoses. |

| Revised WHO 1973 | |

| Grade 1 | Ordered cells with mild nuclear variation, absence of hyperchromasia, maturation to umbrella cell layer and minimal, basally located mitoses |

| Grade 2 | Not 1 or 3 |

| Grade 3 | Variable polarity with disordered layers, hyperchromasia, marked variation in nuclear size, absent umbrella cells and prominent mitotic activity |

| Hybrid grade | |

| Low grade | Delicate papillae, orderly cohesive cells with enlarge oval nuclei showing some variability in nuclear size/shape. Infrequent, basal mitoses. |

| High grade-G2 | Disordered polarity with some nuclear variability and prominent nucleoli, absence of large, hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei, prominent mitotic activity |

| High grade- G3 | Variable polarity with disordered layers, hyperchromasia, marked variation in nuclear size, absent umbrella cells and prominent mitotic activity |

Model-based kappa (κ) measures of association were used to assess interrater agreement.11 The κ estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were stratified by magnification (10× vs. 20×) and practice location (North America vs. Europe). Categories for kappa agreement were as follow: 0–0.20 indicate slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicate fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 indicate moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 indicate substantial agreement, and 0.81–1 indicate almost perfect agreement. See Table S1 for variance and intraclass coefficient estimates from models used in kappa estimation. Statistical analyses were conducted using R v. 4.3.0 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

There were 18 survey respondents: eight North American, eight European, one Australian, and one Indian pathologist. With respect to daily practice, 10 respondents (55.6%) used WHO 2004/2022 grading and eight (44.4%) used both WHO 2004/2022 and WHO 1973 for reporting papillary NMIBC cases. All the European participants used dual/hybrid grading in their daily practice. The majority reported using both 10× and 20× magnification when grading (n = 11, 61.1%), while four (22.2%) used 10× alone, two (11.1%) used 20× alone, and one (5.6%) pathologist used 4× and 10× in their daily practice. One survey respondent skipped two questions and two survey respondents each skipped a single question, leaving 1076/1080 (99.6%) image grading responses for assessment.

There were 30 cases selected, generating 60 images in total. The breakdown of the original assigned grades was as follows: LG, n = 15 (30 images, 50.0%), HG-G2, n = 8 (16 images, 26.7%), and HG-G3, n = 7 (14 images, 23.3%). Table 2 shows the distribution of grade assigned amongst the 1076 responses.

| Study ID | Magnification | LG | HG G2 | HG G3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10× | 15 | 3 | 0 |

| 20× | 14 | 4 | 0 | |

| 2 | 10× | 14 | 3 | 0 |

| 20× | 16 | 2 | 0 | |

| 3 | 10× | 14 | 4 | 0 |

| 20× | 10 | 8 | 0 | |

| 4 | 10× | 4 | 14 | 0 |

| 20× | 7 | 10 | 1 | |

| 5 | 10× | 12 | 6 | 0 |

| 20× | 9 | 9 | 0 | |

| 6 | 10× | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 20× | 16 | 2 | 0 | |

| 7 | 10× | 6 | 12 | 0 |

| 20× | 5 | 13 | 0 | |

| 8 | 10× | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| 20× | 17 | 1 | 0 | |

| 9 | 10× | 15 | 3 | 0 |

| 20× | 16 | 2 | 0 | |

| 10 | 10× | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 20× | 17 | 1 | 0 | |

| 11 | 10× | 8 | 10 | 0 |

| 20× | 6 | 12 | 0 | |

| 12 | 10× | 13 | 4 | 0 |

| 20× | 7 | 11 | 0 | |

| 13 | 10× | 16 | 2 | 0 |

| 20× | 11 | 7 | 0 | |

| 14 | 10× | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 20× | 17 | 1 | 0 | |

| 15 | 10× | 12 | 6 | 0 |

| 20× | 5 | 12 | 0 | |

| 16 | 10× | 2 | 14 | 2 |

| 20× | 1 | 16 | 1 | |

| 17 | 10× | 6 | 12 | 0 |

| 20× | 3 | 12 | 1 | |

| 18 | 10× | 13 | 5 | 0 |

| 20× | 7 | 11 | 0 | |

| 19 | 10× | 0 | 6 | 12 |

| 20× | 0 | 5 | 13 | |

| 20 | 10× | 3 | 13 | 1 |

| 20× | 4 | 13 | 1 | |

| 21 | 10× | 1 | 16 | 1 |

| 20× | 0 | 13 | 5 | |

| 22 | 10× | 1 | 11 | 6 |

| 20× | 1 | 14 | 3 | |

| 23 | 10× | 1 | 14 | 2 |

| 20× | 0 | 8 | 10 | |

| 24 | 10× | 0 | 2 | 16 |

| 20× | 0 | 0 | 18 | |

| 25 | 10× | 0 | 3 | 15 |

| 20× | 0 | 0 | 18 | |

| 26 | 10× | 0 | 3 | 15 |

| 20× | 0 | 1 | 17 | |

| 27 | 10× | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| 20× | 0 | 4 | 14 | |

| 28 | 10× | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| 20× | 0 | 1 | 17 | |

| 29 | 10× | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| 20× | 0 | 0 | 18 | |

| 30 | 10× | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| 20× | 0 | 0 | 18 |

- Assigned grade.

- %, percentage; G2, grade 2; G3, grade 3; HG, high grade; LG, low grade; ×, magnification.

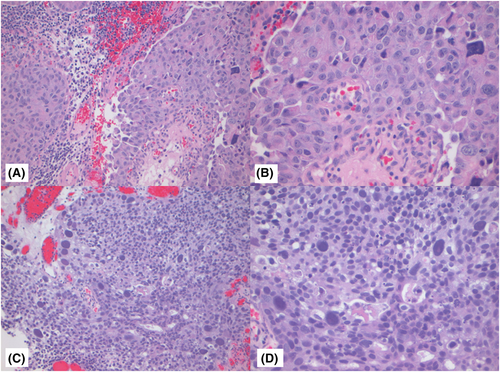

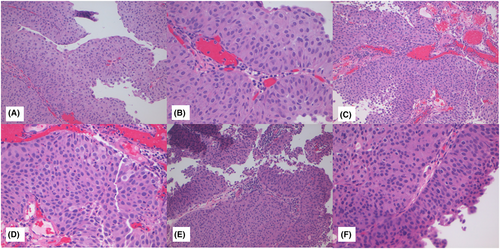

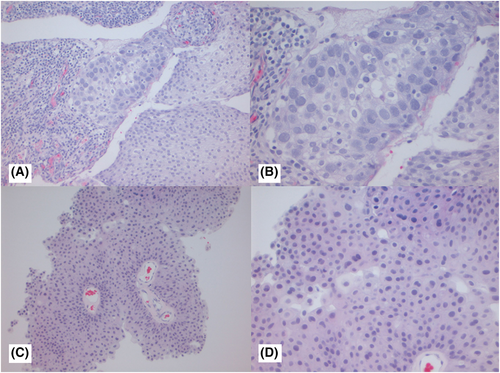

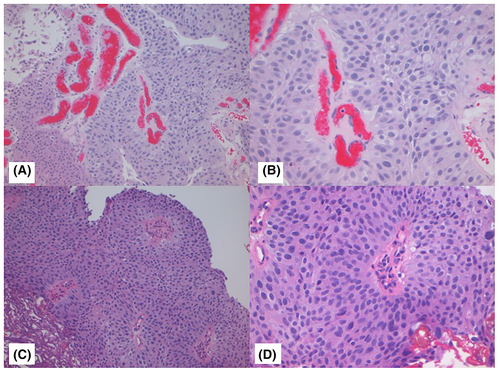

Figures 1-3 show examples of cases with the highest agreement for LG, HG-G2, and HG-G3. Figure 4 shows examples of low agreement for LG and Figures 5 and 6 for HG-G2 bladder cancers.

The κ value for the 10× images (n = 537) was 0.641 (95% CI: 0.557–0.725) and 20× images (n = 539) was 0.623 (95% CI: 0.533–0.714), which is substantial agreement (Table 3) with both North American and European pathologists achieving substantial agreement values with North American κ for 10× images = 0.647 (95% CI: 0.552–0.741) and for 20× images = 0.623 ([95% CI: 0.518–0.728]) The European pathologists' κ for 10× images was = 0.663 (95% CI: 0.585–0.741) and for 20× images was 0.682 (95% CI: 0.593–0.772). The lowest observed κ was for assessment of LG 20× images at κ = 0.241 (95% CI: 0.112–0.369), which represented fair agreement, whereas the HG images at 20× had κ = 0.549 (95% CI: 0.417–0.680) (moderate agreement). Kappa could not be estimated separately for HG-G2 and HG-G3 cases, as all HG-G3 cases were classified as either HG-G2 (16/252) or HG-G3 (236/252).

| Group | Observations | Raters | Kappa | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All images at 10× | 537 | 18 | 0.641 | (0.557, 0.725) |

| North America | 237 | 8 | 0.647 | (0.552, 0.741) |

| Europe | 240 | 8 | 0.663 | (0.585, 0.741) |

| Low grade | 268 | 18 | 0.296 | (0.166, 0.426) |

| High grade | 269 | 18 | 0.529 | (0.393, 0.666) |

| All images at 20× | 539 | 18 | 0.623 | (0.533, 0.714) |

| North America | 240 | 8 | 0.623 | (0.518, 0.728) |

| Europe | 239 | 8 | 0.682 | (0.593, 0.772) |

| Low grade | 239 | 18 | 0.241 | (0.112, 0.369) |

| High grade | 270 | 18 | 0.549 | (0.417, 0.680) |

- Categories for kappa agreement: 0–0.20 indicate slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicate fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 indicate moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 indicate substantial agreement, and 0.81–1 indicate almost perfect agreement.

- CI, confidence interval; ×, magnification.

Discussion

Papillary NMIBC tumours show variability in terms of recurrence and progression. Grade is not a significant factor in determining recurrence; however, grade is highly significant in predicting progression (≥T2).12, 13 Irrespective of the grading system used, both WHO 2004/2022 and WHO 1973 show differences in progression within the carcinoma categories, with LG progressing less than HG (WHO 2004/2022), while progression rates in G3>G2>G1 using WHO 1973. The issue of which system performs better in determining progression was addressed in previous publications,2, 12, 14 which found that a hybrid approach, combining WHO 2004/2022 and WHO 1973 outperformed either system alone. An independent study from North America also showed hybrid grading to be preferential in determining progression, particularly in the HG group, where there was a significant difference between HG-G2 and HG-G3 and less of a difference in the LG-G1 and LG-G2.3 This suggested that a three-tier hybrid grading scheme retaining LG as one category and dividing HG into two categories may be sufficient. The WHO 2004/2022 HG group is a clinically and molecularly15-17 heterogeneous group, with those at the extreme HG (G3 in WHO 1973) showing faster and higher progression rates than those HG cases that correlate with G2 in WHO 1973.18 Therefore, there is merit in subclassifying these HG cases to inform management decisions and ensure appropriate intervention.

The major criticism of WHO 1973 has rightly been the lack of histologic criteria to enable accurate classification of cases. At the Basel ISUP Consensus Meeting, there was general agreement amongst participants that all existing grading schemes could be improved upon and that differentiating LG and HG cases remained a challenge. Further, there was interest in moving towards a hybrid grading scheme.8 Acknowledging the existing challenges in grade assignment, an expert opinion paper published prior to the Basel consensus meeting produced more detailed histologic criteria for distinguishing the WHO 1973 categories.19 These criteria were circulated to the study uropathologists as part of the study instructions.

Half of the participants used WHO 2004/2022 in their day-to-day practice and not WHO 1973 or hybrid grading; however, the kappa values achieved were substantial across all participants. When subanalysed by location of practice (Europe vs. North America), the kappa values, while slightly higher amongst Europeans, were substantial in both cohorts. This suggests that despite many not using hybrid grading currently, it has the potential to be adopted reasonably quickly. A key finding from our study was the near unanimous agreement in identifying the HG-G3 cases, arguably the most detrimental cases. Not surprising, and in keeping with survey data from the Basel consensus meeting,8 was the difficulty in separating HG-G2 and LG cases. The advantage of hybrid- three-tier grading is that when a case is assigned HG-G3, there is no uncertainty on the treating clinician's part as to whether it is an LG or HG case, whereas a HG-G2 conveys that the carcinoma is closer to the border of LG.

Another finding from this work was the stated preference of pathologists to grade using two magnifications (10× and 20×). Unlike other genitourinary cancers such as renal cell carcinoma20 and prostatic adenocarcinoma,21, 22 there have been no recommendations on what magnification(s) to use to grade papillary NMIBC. While agreement using 10× and 20× were similar, there were slightly better overall kappa values for 10× image gradings compared with the 20× images gradings.

The three major limitations of this study were the inclusion of expert urologic pathologists with interest in bladder pathology, which raises the issue of whether the same results would be found amongst a larger group of nonspecialized pathologists. The cases were also selected from only two institutions, so while cases with variable H&E staining were included, in the real-world setting there would inevitably be greater variability in the intensity/quality of the staining, which could potentially impact grading assessments. Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) cases are infrequent and were not included in this study. However, they would be considered part of the LG spectrum of cases in terms of grading19 and some pathologists who use the terminology of PUNLMP may have called some cases this entity if that option had been available and the age/clinical scenario were appropriate. Finally, we selected static images as the modality of choice to ensure the images were reviewed by participants at the 10× and 20× magnifications. Supplying scanned images could have introduced an element of zooming and toggling between multiple magnifications. It is possible that using a less rigid modality than forced grading on static images may have improved the results, but this could only be addressed in a dedicated digital versus static images study. In real-world practice, grading will likely be performed by most pathologists using both 10× and 20× magnification, similar to our study participants.

In conclusion, hybrid grading of papillary Ta NMIBC showed substantial agreement as assessed by interrater kappa values. This was higher than reported in prior studies that assessed agreement using WHO 1973 and WHO 2004/2022.8 Pathologists readily recognize HG- G3 cases, but challenges still remain within the HG-G2 category. We also show that similar kappa values for grading were achieved using 10× and 20× magnification and we are, to our knowledge, the first group to specifically assess magnification as a factor in grade assignment in papillary urothelial carcinomas. Our results show that urologic pathologists can readily adapt to using a three-tier hybrid grading system with good interrater agreement. Our positive findings should encourage much needed further clinicopathologic studies using these well-defined criteria so that future iterations of classification system revisions can incorporate refinements based on demonstrated clinical impact.

Author contributions

M.R.D. and T.H.v.d.K. designed the study, performed the research, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted and critically revised the article. K.L. analysed the data and contributed to the review and editing of the article. F.A., Y.A., M.B.A., L.C., S.D., M.E., A.H., A.L.B., S.M., M.L.v.M., J.O., G.P.P., H.S., S.S., J.W., S.R.W., and S.E.W. performed the research and contributed to the review and editing of the article. All authors have read and approved the submitted and final versions of the article.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented, in part, at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology Annual Meeting, Baltimore, Maryland on March 27th 2024.

Funding information

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicting interests to disclose.

Open Research

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.