Understanding stakeholder important outcomes and perceptions of equity, acceptability and feasibility of a care model for haemophilia management in the US: a qualitative study

Abstract

Introduction

Care for persons with haemophilia (PWH) is most commonly delivered through the integrated care model used by Hemophilia Treatment Centers (HTCs). Although this model is widely accepted as the gold standard for the management of haemophilia; there is little evidence comparing different care models.

Aim

We performed a qualitative study to gain insight into issues related to outcomes, acceptability, equity and feasibility of different care models operating in the US.

Methods

We used a qualitative descriptive approach with semi-structured interviews. Purposive sampling was used to recruit individuals with experience providing or receiving care for haemophilia in the US through either an integrated care centre, a specialty pharmacy or homecare company, or by a specialist in a non-specialized centre. Persons with haemophilia, parents of PWH aged ≤18, healthcare providers, insurance company representatives and policy developers were invited to participate.

Results and Conclusions

Twenty-nine interviews were conducted with participants representing 18 US states. Participants in the study sample had experience receiving or providing care predominantly within an HTC setting. Integrated care at HTCs was highly acceptable to participants, who appreciated the value of specialized, expert care in a multidisciplinary team setting. Equity and feasibility issues were primarily related to health insurance and funding limitations. Additional research is required to document the impact of care on health and psychosocial outcomes and identify effective ways to facilitate equitable access to haemophilia treatment and care.

Introduction

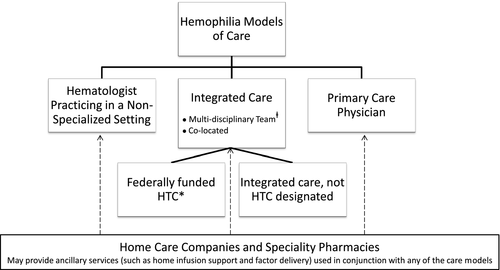

Persons with haemophilia (PWH) not only require medical care for prevention and treatment of bleeds but also have other health and psychosocial needs 1. Care for PWH is most commonly delivered through an integrated care model (otherwise known as ‘comprehensive care’) (Hemophilia Treatment Centers [HTC]), which provides all components of haemophilia care through coordinated and geographically co-located multidisciplinary teams 2-4. PWH can also access care from haematologists practicing in a non-specialized setting, or in some cases from a primary care physician. Some PWH also utilize the ancillary services of homecare companies or speciality pharmacies (Fig. 1). The integrated care model is widely accepted as the standard of care for haemophilia; however, there is little evidence comparing different care models. Recently, the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF) of the United States (US) partnered with McMaster University to develop a guideline on care models for haemophilia management using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach 5. This process identified a paucity of evidence to inform panel members’ decisions pertaining to: equity, acceptability and feasibility.

Therefore, a qualitative study was performed to gain insight into issues related to equity, acceptability, feasibility and the impact of different care models operating in the US. From the study outset, the broad objective was to explore and understand the perspectives of key stakeholders with experience providing or receiving haemophilia-related care and services in the US in one or more of the care models described above. As the study progressed, the specific objectives were refined to reflect the study sample, which consisted predominantly of stakeholders with experience providing or receiving care within HTCs, representative of the integrated care model in the US. The refined objectives were to identify and describe the health and psychosocial outcomes of importance to stakeholders, the equity issues related to accessing care, the factors related to the acceptability and the feasibility and sustainability of the integrated care model.

Methods

An iterative, qualitative descriptive approach 6 was used to pursue the study objectives. This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Sampling and recruitment

A form of stratified purposive sampling known as ‘stakeholder sampling’ 7 was used to recruit individuals with experience providing or receiving care for haemophilia in the US through either a HTC, a specialty pharmacy or homecare company, or by a specialist in a non-specialized setting. People with haemophilia, parents of PWH aged 18 and under, healthcare providers (including haematologists, nurses, physical therapists [PTs], and social workers), insurance company representatives and individuals involved in policy development were invited to participate.

Numerous approaches were used to recruit participants including: postings on the NHF's Twitter account and Facebook page containing a link to the project website; email invitations to NHF chapter presidents, NHF's insurance payer panel, and a random sample of healthcare providers at HTCs (nurses, haematologists, PTs, and social workers); and haematologists (using contact information available through the American Society of Hematology online member directory); as well as emails to administrative and managerial personnel at homecare and specialty pharmacy companies requesting them to forward the email invitation to healthcare providers within their organizations. Emails to personal contacts and snowball sampling 8 were also used to enhance recruitment.

Individuals interested in participating were asked to contact the study coordinator, provide consent and schedule an interview. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to interviewing.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured telephone interviews (lasting 25–60 min) were conducted in English between February 2015 and February 2016 by an experienced interviewer. Interview guides contained open-ended questions that varied slightly by stakeholder group (examples in Appendix A). The guides were revised after the first few interviews to ensure that the data elicited were relevant to the study objectives. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were anonymized, checked for accuracy and imported into NVivo qualitative data analysis Software (version 10, 2012, QSR; International Pty Ltd. Melbourne, Australia).

A modified, conventional qualitative content analysis 6, 9 was used to analyse the interview data. Four members of the research team (SJL, NSS, CHTY and MP) independently reviewed a subset of the transcripts to identify and label categories or ‘codes’ in the data 10. Codes were compared, discussed and organized into a coding scheme, which was applied to the same interview independently by two analysts (SJL, NSS) using NVivo qualitative data analysis Software (version 10, 2012, QSR; International Pty. Ltd. Melbourne, Australia). The coding scheme was structured using the four major themes from the study objectives that guided data collection: outcomes of importance to stakeholders, impact of care on health inequities, acceptability of care, and feasibility of sustaining or implementing care (definitions and rationale in Table 1). A coding comparison query was run to assess inter-rater agreement and codes below 90% agreement were reviewed and discussed, and descriptions were clarified. The final version of the coding scheme was applied to all interviews by one member of the team (SJL). Reports of the data in each code were reviewed and summarized by two members of the team (SJL, NSS). Illustrative quotations were selected and are presented in Appendix S1. The majority of study participants referred to integrated care as ‘comprehensive care’; this language is used to report the study results.

| Topics explored in study | Definition/Rationale |

|---|---|

| Health and psychosocial outcomes | A focus on health and psychosocial outcomes helps to establish the goals or results that that stakeholders expect from their healthcare activities |

| Equity issues | Equity in health care is an important dimension to explore in order to understand the extent to which healthcare services or systems deal fairly with all concerned; equity is closely related to access and the distribution of healthcare and its benefits among people 11. |

| Factors related to acceptability | Acceptability can be understood as the extent to which a healthcare system or service conforms to the realistic wishes, desires and expectations of healthcare users and their families 11, 12. |

| Feasibility and sustainability | The concept of feasibility is related to the availability or sustainability required resources which may include personnel, material resources, or technology, and can also encompass the broader environmental issues related to implementation 13. |

Results

A total of 29 interviews were conducted with participants representing 18 different US states, with perspectives on at least 26 HTCs. A breakdown of participants’ roles and perspectives are summarized in Table 2. With the exception of policy developers, who shared a general perspective, all participants in the study sample had experience receiving or providing care within an HTC setting. Some participants had experience using both an HTC and homecare services. The majority of study participants who received or provided care at an HTC did so in a hospital-based HTC serving either adult or paediatric PWH or both. A few participants provided care in a stand-alone HTC, not located in a hospital.

| Stakeholders | Number of interviews categorized by type of care | Number of perspectives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTC only | HTC and homecare | ||

| PWH | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Parent of PWH | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Haematologist | 7a | 0 | 7 |

| Nurse | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Physical Therapist | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Social Worker | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Policy Developers | n/a | n/a | 3 |

| Insurance Representative | n/a | n/a | 0 |

| Totalb | 30 | ||

- a One haematologist provided care in both an HTC and a hospital without an HTC.

- b One participant shared the perspectives of both a PWH and a parent; therefore, there are 29 interviews and 30 perspectives.

- HTC, Haemophilia Treatment Centre; n/a, not applicable.

Clinical and psychosocial outcomes

Participants identified a variety of clinical and psychosocial health outcomes that they were trying to achieve. Commonly identified clinical outcomes included: joint health; prevention of bleeds; adherence to treatment; and pain management. Prevention of inhibitors and minimization of hospitalization or visits to the emergency room were identified by fewer participants. A couple of healthcare providers identified reduction in mortality as an important goal of haemophilia treatment and care.

The psychosocial outcomes most often identified by participants included: living a normal life; quality of life; school or work attendance; securing appropriate employment (i.e. consideration of physical demand and healthcare coverage); mental health; and the ability to participate in sport. Less frequently reported psychosocial outcomes included being autonomous and having good knowledge of haemophilia. Almost all participants unequivocally believed that the comprehensive care HTC model helped improve health outcomes, though the lack of evidence supporting this belief was noted by a couple of participants.

Acceptability

Many aspects of care provided by HTCs were valued and appreciated by participants. Some believed that the care PWH received at an HTC was better than the care available at other settings and suggested that PWH who do not have access to comprehensive care though an HTC may not be receiving state of the art care.

Comprehensive care

Participants stressed the importance of the comprehensive care approach and perceived benefits to receiving and providing multidisciplinary and holistic care in one place including: convenience; continuity of care; and team cohesiveness. However, a couple of providers described the challenge of ensuring that all members of the HTC team provide consistent information to patients. At some of the HTCs, the continuity of core staff had been maintained over many years, which was considered an asset appreciated by PWH and families. A few providers indicated that at some larger HTCs, the lack of continuity of providers was considered to be an area for improvement. Overall, participants perceived that the comprehensive care model helped to improve health outcomes.

A couple of participants conveyed the need to further define and/or create standards for the provision of care in the comprehensive care model. Several participants emphasized the importance of care being truly comprehensive, which meant having access to all members of the multidisciplinary team. Although PTs were considered an essential component of the comprehensive care team, the PT role and services varied considerably between HTCs and were perceived in some cases to be inadequate. The number of dedicated PT hours at HTCs reported by participants varied considerably, from 4.5 h per week, to 23 and 32 h per week. While some HTCs had full-time PTs, participants indicated most PTs tend to be employed part time. At some HTCs, PTs were only able to provide care during comprehensive care clinic visits; few PTs have the opportunity to follow-up with PWH on a rehabilitative outpatient basis.

Medical expertise

The specialized knowledge and expertise possessed by healthcare providers at HTCs was perceived as unique and was highly valued by study participants. Healthcare providers’ ‘excellent’ clinical care and up-to-date advice were also appreciated by participants. There was a perception that experience garnered from providing care in an HTC and being part of a network of HTCs helped to foster medical expertise among healthcare providers. In contrast, some participants described negative experiences in hospital emergency room settings as a result of a general lack of understanding of haemophilia among emergency room staff.

Staff familiarity and patient-centred approach

The relationships and the level of familiarity fostered between PWH, their families and healthcare providers were also valued. Several participants appreciated the humanistic, individualized and patient-centred approach to care at the HTCs. A couple of parents of PWH believed that the HTCs approach of engaging children with haemophilia directly in their own care helped to foster children's independence and responsibility for their health.

Ease of access to treatment and care

The ease with which PWH and families were able to access appointments and medical advice was an important aspect of acceptability. Participants' experiences booking appointments at HTCs varied: it was easy for some individuals, whereas others found it difficult due to a lack of flexibility. Although access to the multidisciplinary team during the comprehensive care clinic appointments was valued, some clinic staff acknowledged that the length of appointments, which could last between 2 and 4 h, could be cumbersome for some PWH and families.

Participants highlighted the ease with which PWH and families could contact providers at the HTC by phone to discuss treatment and care needs; a service that can be particularly helpful for patients who live a greater distance from the HTC. Telephone access for medical advice from HTCs after-hours varied. At some HTCs, the staff could be contacted directly but more commonly, access to advice after-hours was obtained by calling the haematologist on-call at the hospital where the HTC was located. After-hours services generally met or exceeded participants’ expectations.

Valued HTC roles

HTCs fulfil a number of roles that were valued by participants. HTCs were considered an excellent source of information and education for PWH, families, the broader community and schools. HTCs provide individuals with vital information about treatment options and practices, and teach skills such as bleed identification and management. HTCs offer PWH and their parents emotional and psychosocial support.

HTCs collaborate and consult with other healthcare providers, and coordinate patient visits to the emergency room when necessary to ensure optimal patient care. Physical therapists at the HTC may advise outpatient PTs on how to best manage and care for people with haemophilia. Several participants appreciated the monitoring of joint status and joint health over time to identify and address problems as they arise.

Homecare and/or specialty pharmacy services

In addition to the services accessed through HTCs, a number of participants had used the home-based infusion services provided by homecare companies and valued the convenience and comfort of receiving infusion assistance or instruction from a nurse in the home. One individual believed that the comfort of learning how to infuse in their home contributed to ease of learning this new skill. Other examples when home infusion services were used included infusion support for young children with difficult venous access and postsurgery assistance. Two participants appreciated the personal relationships they had developed with home care nurses and other staff.

Equity

A number of equity issues that could limit or restrict access to HTCs were identified, including: insurance coverage; managed health plans; proximity to an HTC; language; culture; and sex. Participants also discussed strategies that have been used to overcome these barriers.

Insurance and managed health plans

Insurance coverage, managed health organizations and health plans can dictate where individuals are able to receive treatment and care. In some cases, this has precluded individuals from being able to access treatment and care at an HTC or restricted choice of which home care company or speciality pharmacy people can use. It can be challenging for patients to navigate healthcare insurance and ensure they choose the most appropriate plan to meet their haemophilia needs. Some people have had a difficult time obtaining adequate insurance coverage, whereas others had no insurance issues. Social workers, nurses and haematologists at HTCs help people to understand their insurance options and make choices about health plans that best suit their needs.

A few participants indicated that although the Affordable Care Act has increased access to insurance coverage, required ‘out-of-pocket’ payments can be a barrier for some individuals. Out-of-pocket costs (co-pays, co-insurance and ‘high’ deductibles) can be a limiting factor in terms of accessing treatment and care. One participant described a paradox where working people have insurance coverage, but can still experience limitations to accessing care because of high deductibles.

Health Maintenance Organizations often require PWH to access care from health care providers or hospitals within their select provider group or network, which may not include an HTC. People with Medicaid insurance who are served through Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) can experience similar barriers to accessing care at an HTC. Sometimes PWH who do not have coverage to be seen routinely at an HTC are able to negotiate with their MCO to attend an HTC once per year for an annual review. A few participants noted that the quality of haemophilia care that PWH may receive from physicians within closed model health plans (outside an HTC) can vary depending on the physicians’ level of haemophilia knowledge and expertise.

There are some federal and state programmes that provide financial coverage for treatment and care for children with haemophilia. PWH and parents described experiences when their employment decisions were driven by the need to obtain or maintain adequate insurance coverage. A couple of participants had experienced fear of being pushed out of their job or not being hired by a company due to having a pre-existing condition with expensive medical costs. A couple of haematologists indicated that when young adults transition from their parent's insurance to their own, the subsequent changes may result in some individuals being underinsured.

Providers discussed the challenges associated with providing care for people without insurance such as ‘undocumented’ immigrants who do not have American citizenship. In these circumstances, HTCs do their best to provide treatment and care and guide people to alternative ‘charity’ or ‘compassionate’ care programmes, which grant them access to some services through the HTC. HTCs also help people without insurance by liaising with pharmaceutical companies to obtain factor on compassionate grounds.

Additional barriers to accessing care

Some participants reported that women with haemophilia can experience difficulties being diagnosed and obtaining adequate care and management. Lack of awareness that haemophilia is a disease that sometimes affects women can result in insurance restrictions. Culture and language barriers (i.e. lack of translation services) were also perceived by some participants to impede access to care. Sometimes, individuals may not be aware that HTCs exist; in some cases, local haematologists may not make a referral to an HTC.

Proximity

Analysis revealed that the geographic distribution of HTCs across the US varies. Some states do not have an HTC, while others have more than one. Some HTCs serve a wide catchment zone requiring PWH to travel extensive distances to obtain care; in other cases, there are multiple HTCs in a state or region. Travel times to an HTC reported by participants varied from 10 min up to 8 h. Travel distance can be a barrier to attending HTC appointments and can be compounded by low socioeconomic status. Some PWH or parents may not be able to afford to take time off work, or to afford the costs of gas and overnight accommodation.

Travelling long distances can be a deterrent to accessing care at an HTC and some PWH may opt to be seen by a local haematologist while also attending their HTC annually or bi-annually. In these situations, HTCs may collaborate with physicians in local communities to advice and direct care.

Outreach

In an effort to help overcome the geographic barriers that PWH experience, participants reported some HTCs hold outreach clinics in remote areas or use telemedicine including videoconferencing to perform assessments and manage care. Although telemedicine can minimize the financial burdens related to travel and time away from work, it requires that people have access to a computer and the internet. Some HTCs directly or in collaboration with patient organizations provide educational outreach to other communities, healthcare providers, PWH and families, and schools to inform them about haemophilia and equip them with the knowledge and skills they require to better manage the disease. The ability to provide outreach is contingent on funding.

Feasibility

A number of participants acknowledged that haemophilia is an expensive disease to treat and manage, due to the high costs of factor concentrates and care.

Funding

Funding was identified as having the greatest potential to affect the sustainability of comprehensive care at HTCs. HTCs have historically relied on government funding to provide comprehensive services; however, several participants noted that government funding for HTCs has been in continuous decline, making it challenging for some HTCs to ‘keep the staff at a level commensurate with the needs of the patient population’ (Nurse). Some participants asserted that the current healthcare reimbursement model is a poor fit for how haemophilia is managed today. Advances in haemophilia care have led to a paradigm shift from hospital-based care to outpatient, self-managed, home-based care; many of the services required and provided by HTCs today (i.e. phone consultations and coordinating care) are not typically reimbursed by insurers.

340B Drug Discount Program

The 340B Drug Discount Program was established in 1992 to enable certain health care providers to better serve low-income or medically vulnerable populations by requiring drug manufacturers to provide outpatient drugs to ‘covered entities’ such as HTCs at significantly reduced prices 14. HTCs are required to reinvest the revenue generated by the 340B program to maintain and expand services for PWH 15. Participants perceive that many HTCs rely on the revenue generated by 340B pharmacies to sustain comprehensive care. Some participants noted that 340B programs are susceptible to political changes within the federal government.

Infrastructure

The findings suggest that the funding available to HTCs varies and can influence the institutional and intellectual resources, staff and services available. Some HTCs are better resourced than others and can provide a greater range of multidisciplinary services. Several participants spoke directly to the point that HTCs across the US differ significantly from one another.

Although, the core care team at most HTCs consists of at least one haematologist, nurse, social worker and PT, the availability and range of social worker and PT services varied. Some HTCs have a dedicated PT who is part of the comprehensive care team, whereas more often, PTs are contracted from hospitals for a set amount of hours per week. These differences in employment arrangements affect the level of service that PTs can provide.

Depending on resources, HTCs may provide access to a range of additional healthcare specialists (i.e. psychologist, orthopaedic surgeons, dental services and/or geneticists). Some participants perceived that there may be a shortage of haematologists with specialization in haemophilia treatment and care. Participants perceived that some HTCs, access to orthopaedists is limited by the trend towards greater joint specialization within the orthopaedic field resulting in a shift away from haemophilia informed orthopaedic care. Sometimes, HTCs at smaller hospitals may not have access to orthopaedists at all.

Discussion and conclusion

Although there is limited evidence to support the impact of integrated care on clinical and psychosocial outcomes, this approach is commonly considered to be the superior care model for the management of haemophilia 16. The integrated care model embodied by the HTC was highly acceptable to participants in this study who appreciated the value of providing or receiving specialized care in a multidisciplinary, team setting by individuals with haemophilia expertise. This finding mirrors ‘the positive picture of the care and services’ at HTCs reported by a recent national needs assessment 17.

Our findings show that the major equity and feasibility issues are interconnected and relate back to health insurance and HTC funding. Barriers to adequate HTC access include: out of pocket expenses and health insurance restrictions or limitations. The ability of HTCs to provide and sustain standardized, integrated care and services is contingent on funding. Despite the limitations posed by these equity and feasibility challenges, staff at HTCs go above and beyond to find solutions and circumvent these healthcare systems level issues.

The aim of this study was to identify and describe stakeholder important outcomes and the factors and issues related to acceptability, equity and feasibility regarding the different ways of providing or receiving haemophilia care in the US. Our study primarily elicited the perspectives of individuals with experience providing or receiving care within the integrated care (i.e. comprehensive care), HTC setting. Despite a comprehensive recruitment strategy, we did not obtain representation from insurance providers or individuals providing or receiving care in other settings. This lack of participation limited our ability to conduct a stratified analysis by stakeholder perspective or models of care. Findings from the CHOICE project 18, may provide additional insights into the health experiences of people with bleeding disorders who do not receive care at a federally funded HTC.

The strengths of our study design included the following measures to ensure trustworthiness 19: using a team approach to analyse data and report findings, (analyst triangulation) 20; increasing the breadth and credibility of findings by sampling a range of stakeholder with different perspectives (data source triangulation) 21; and keeping an audit trail to track the research process and decisions 22. The transferability of study findings must be assessed by the reader, or practitioners in the field 19. We have strived to provide sufficient contextual detail, so the reader is able assess transferability to other settings with ease.

Although this study provided a glimpse into the challenges that women and carriers of haemophilia experience, further research is required to better understand and address the access to care issues for this population. Additional research is required to document the impact of care on health and psychosocial outcomes and identify effective ways to facilitate equitable access to haemophilia treatment and care.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Hemophilia Foundation. The study was designed by AI, SJL and MP. SJL performed data collection and SJL and NSS lead the analysis with input from CHTY and MP. SJL and NSS wrote the manuscript with assistance from NMH, AI, MS, and CHTY. This manuscript reports a research project subsequently used in the process of the NHF-McMaster Guideline on Care Models for Haemophilia Management. The NHF-McMaster Guideline on Care Models for Haemophilia Management have been endorsed by the World Federation of Hemophilia (May 20, 2016), the American Society of Hematology (May 27, 2016), the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis (May 28, 2016).

Disclosures

CHTY and NSS have stated that they had no interests which might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias. NMH receives infrastructure funding for the McMaster Centre for Transfusion Research from Canadian Blood Services and Health Canada and has received funding through Pfizer/Canadian Hemophilia Society, Care Until Cure grant. SL has received consulting honoraria from Novo Nordisk, and honoraria for speaking engagements from Bayer and the Canadian Hemophilia Society. MS received unrestricted research fellowship funding support from Baxter Pharmaceuticals. AI has received funds for consulting from Bayer and Biogen Idec; research support from NovoNordisk, Biogen Idec, and Pfizer; all funding has been directed to McMaster University and none received as a personal honorarium; and works at a non-US HTC. MP has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Bayer; and consulting income from Bayer, BMS-Pfizer and Sanofi.

Appendix A: Interview Guides

Healthcare Providers Interview Guide

Demographic Questions

- What is your role in providing care to people with haemophilia?

- What other professionals do you work with?

- How long have you been providing care to PWH?

Care Questions

- Where do you work? Have you ever provided care anywhere else? Were there any differences in how care was provided between ____ and ____.

- In providing haemophilia treatment and care, what patient health and psychosocial outcomes are important?

- When it comes to haemophilia treatment and care what does your HTC do well? What are the things that could be improved?

- What do patients tell you they most appreciate about receiving care at your HTC? What do patients tell you they least appreciate about receiving care at your HTC?

- Are there PWH for whom access to care or treatment at your HTC is a concern? What are the reasons for this?

- Drawing on your experience practicing in the field, does the way a person receives care affect their health status or health outcomes? How?

- What are the challenges you experience in providing care at your HTC? Is there anything you can think of that might prevent your HTC from continuing to provide care this way in the future?

PWH Interview Guide

Demographic Questions

- What kind of haemophilia do you have and what severity?

- How old are you?

- Where do you live? How far away do you live from the place you receive care for haemophilia?

Care Questions

- Where do you receive care for haemophilia? How often do you attend? Is this the only place you need to go to get all of your haemophilia care needs met? Have you ever received care in a different way? Where? When? Why?

- Have you ever used a Homecare Company? What services?

- How do you access factor concentrates?

- Can you tell me why are you getting care this way?

- What kind of medical coverage do you have for your haemophilia care? Are there any limitations to your coverage?

- In addition to prescribing treatment, can you describe anything else your healthcare provider/healthcare team does to help you take care of haemophilia? How does this help?

- In treating and caring for haemophilia, what results are you trying achieve? What results are most important to you?

- What do you like about the services you receive? Is there anything you dislike about the services you receive?

- What kinds of things make it easy or hard to connect with the HTC/specialty pharmacy? How do you access care after hours?

- Are you aware of any other way of obtaining care for haemophilia that you would like to access but are unable to do so? What is preventing you from doing so? Do you know anyone with haemophilia who you think would benefit from receiving care/services this way, but who is unable to do so? What's preventing them?

- In your opinion does the way a person receives care affect their health status or health outcomes? How?