“Family Connections”, a program for relatives of people with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial

Abstract

Family members of people with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) often experience high levels of psychological symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or burden. Family Connections (FC) is a pioneer program designed for relatives of people with BPD, and it is the most empirically supported treatment thus far. The aim of this study was to carry out a randomized clinical trial to confirm the differential efficacy of FC versus an active treatment as usual (TAU) in relatives of people with BPD in a Spanish population sample. The sample consisted of 121 family members (82 family units) and a total of 82 patients who participated in a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT). The primary outcome was burden of illness. Secondary outcomes were depression, anxiety, stress, family empowerment, and quality of life. This is the first study to evaluate relatives and patients in an RCT design comparing two active treatment conditions of similar durations. Although no statistically significant differences were found between conditions. However, the adjusted posttest means for FC were systematically better than for TAU, and the effect sizes were larger in burden, stress, depression, family functioning, and quality of life in the FC intervention. Patients of caregivers who received the FC condition showed statistically significant improvements in stress, depression, and anxiety. Results indicated that FC helped both patients and relatives pointing to the importance of involving families of patients with severe psychological disorders.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is considered an important public mental health problem with strong repercussions that also causes great suffering for those affected and their relatives (Fruzzetti et al., 2005). The results of different studies show high levels of suffering, psychological problems, and burden of illness in relatives of people with BPD (Hoffman et al., 1999; Hoffman & Fruzzetti, 2007). In addition, lack of information and understanding about BPD and its course leads to increased levels of depression and caregiver burden (Hoffman et al., 2003; Rajalin et al., 2009). However, lower levels of relapse, better recovery, and greater family well-being are found when family members participate in treatment (Dixon et al., 2001). Research over the last decade has shown that improvement for relatives is possible when relatives' needs for information, clinical guidance and support are met (Flynn et al., 2017).

Currently, different empirically supported family interventions are presented in group with different formats and contents. There are interventions with a psycho-educational format (Pearce et al., 2017), and other interventions focusing on skills training, in addition to the psychoeducational component, almost all of which are based on DBT skills (Hoffman et al., 2005; Hoffman & Fruzzetti, 2007; Miller & Skerven, 2017; Wilks et al., 2017). The most empirically supported skills training program for family members of people with BPD is Family Connections (FC; Hoffman et al., 2005), an intervention that can be run by both professionals and trained family members. FC was designed by Perry Hoffman and Alan Fruzzetti more than 20 years ago (Hoffman et al., 2005; Hoffman & Fruzzetti, 2007) and was promoted by the National Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder Education. Regarding the efficacy of FC, to date, two pilot studies (Hoffman et al., 2005; Hoffman & Fruzzetti, 2007), a mixed descriptive study (Ekdahl et al., 2014), and two non-randomized controlled studies (Flynn et al., 2017; Liljedahl et al., 2019) have been published. The results of these studies on FC were consistent and maintained or improved at the follow-ups (3 or 6 months), with significant decreases in psychological symptoms such as burden, grief, anxiety, and depression, as well as significant increases in caregivers' perceived mastery and empowerment, well-being, and functioning within the family environment. These promising results could be because FC helps to understand the problems of persons with BPD, improves caregivers' perceived mastery and empowerment, decreases suffering and psychological problems, improves interpersonal relationships, teaches validation to their loved ones (Liljedahl et al., 2019).

These prior studies testing the effectiveness of FC have used burden as primary, and depressive or anxious symptoms, grief, and family empowerment and mastery as secondary outcome measures (Flynn et al., 2017; Guillén et al., 2022; Hoffman et al., 2005; Hoffman & Fruzzetti, 2007). Other authors later introduced other measurement variables such as quality of life (Rajalin et al., 2009) or global family functioning, and family climate (Liljedahl et al., 2019) as secondary measures.

Given the data obtained so far, it seems necessary to take this line of research one step further. The present study aims to advance in exploring the efficacy of FC by carrying out a randomized controlled trial. The Flynn study compared FC Intervention (a 12-week intervention with a total of 24 h) with TAU-Optimized (a 3-h psychoeducational intervention), in a non-randomized controlled study (Flynn et al., 2017). Furthermore, the authors analyzed the data corresponding to the family members, not the patients. The Liljedahl study compares FC at two different intensities (the original FC applied in 12 weeks vs. FC applied in two intensive weekends) in a non-randomized controlled study (Liljedahl et al., 2019). To our knowledge, the present study is the first randomized controlled clinical trial comparing the FC program with another active intervention for the treatment of family members of people with BPD. In addition, it is the first study of FC in the Spanish-speaking population and provides data measuring the family climate in relation to the improvements obtained, both in family members and patients.

This study had three objectives. The first was to investigate the differential efficacy of FC versus an active treatment as usual (TAU) condition in relatives of people with BPD in a randomized clinical trial in specialized care in a Spanish population sample. The second objective was to separately examine whether both conditions separately (FC and TAU) produced an improvement in their participants from pretest to posttest and follow-up. A third objective was to analyze whether both conditions separately (FC and TAU) produced an improvement in their patients with BPD participants. Three hypotheses were proposed. In relation to the first objective, the FC condition should be significantly superior to the TAU condition on the primary outcomes considered here. Regarding the second objective, both FC and TAU should significantly reduce psychological symptoms and illness burden and improve overall family functioning at posttest, and these benefits should be maintained at the follow-up (6 months). Regarding the third hypothesis, both interventions for family members will produce improvements in BPD patients in both experimental conditions, FC and TAU.

METHOD

Study design

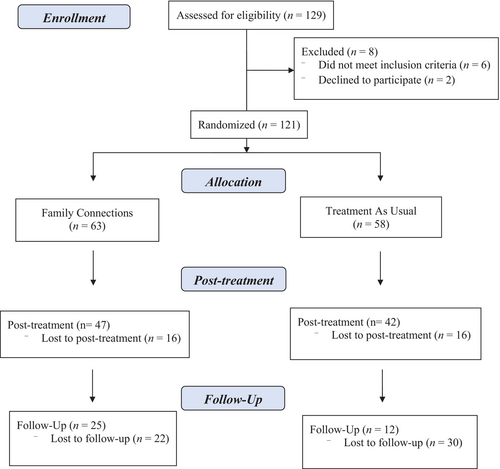

A two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) with repeated measures at pre- and post-treatment and 6-month follow-up was designed following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines (CONSORT, http://www.consort-statement.org; Moher et al., 2001, 2010). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: Family Connections (FC) or Treatment as Usual (TAU). This was a multicenter randomized controlled trial registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04160871). The protocol was also published in Fernández-Felipe et al. (2020). The sample consisted of 121 family members (82 family units) and a total of 82 patients. See Figure 1 for a CONSORT flow diagram.

Participants

The study was conducted in three Specialized Units for Personality Disorders in Spain (Valencia, Alicante, and Castellón) that provide psychological treatment to people with personality disorders and support for their relatives. These clinical centers have a day hospital, a residential unit (24-h care), and outpatient therapy. The intervention was offered to relatives of people who were receiving treatment in these centers, regardless of the specific unit or care setting where they were receiving treatment. Regarding the treatment, all the patients received a protocol based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for patients with BPD (Linehan, 1993), most of the patient's received treatment on an outpatient basis. Once the study had been explained to the relatives, they were offered the opportunity to participate in it. Interested family members signed the informed consent form and, if they accepted, the clinical psychologists screened them to verify that they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The clinical evaluations lasted approximately 1 h each. Participants agreed (or not) to participate before learning which intervention condition they would be assigned to. All participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time. Access and participation in the study did not involve payment. Participants completed the evaluation protocol at three points in time: pre, post, and 6-month follow-up.

A total of 129 relatives of people with BPD were evaluated in these clinical center's during recruitment, and 8 relatives were excluded. Of these, 6 relatives were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 2 relatives refused to participate. In the end, 121 relatives met the inclusion criteria. Participants who fulfilled all the study criteria were randomized by blocks of families to one of the two experimental conditions (FC vs. TAU), using a computer number generated by an independent researcher. This researcher was unaware of the characteristics of the study and had no clinical involvement in the trial. The study used a central randomization strategy. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (a) being over 18 years of age, (b) having a family member diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Edition (DSM-5), and (c) having the ability to understand and read Spanish and provide informed consent.

The sample size was calculated based on effect sizes from studies with caregivers of people with BPD. A controlled study by Grenyer et al. (2019) found medium to large effect sizes (dyadic adjustment, d = 0.78; family empowerment, d = 1.40; burden, d = 0.45). Based on these results, we could expect an effect size of 0.60 considering an alpha of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.80 on a two-tailed t-test; we would need a total sample size of 90 participants (45 per group). However, being conservative about dropouts, and given that a dropout rate of 29% would be expected based on the previous literature (Flynn et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2005), the total sample size should contain at least 116 participants (58 in each experimental condition). Sample size calculations were performed using the G*Power 3.1 software (Faul et al., 2007).

Interventions

Family connections intervention

The Family Connections (FC) program is a manualized, educational, skills training, and support program (Hoffman et al., 2005). The manual was translated by Domingo Marqués, who leads a clinical and research team of experts in DBT in Puerto Rico. Our research team adapted the manual to the Spanish culture and translated the videos that support the program (Spanish subtitles and audio). FC consists of six modules containing two sessions each. Each session lasts 2 h. The first two modules are psycho-educational: 1. Introduction; 2. Family Education. The rest are skills training modules; 3. Relationship Mindfulness Skills; 4. Family Environment Skills; 5. Validation Skills; 6. Problem Management Skills. Each module has specific objectives and practical exercises, as well as videos with examples of people suffering from BPD and their relatives.

Treatment as usual

The TAU intervention consists of six modules (12 sessions) lasting 2 h each. This program was created by the clinical center; it is based on DBT skills and cognitive behavioral therapy. The intervention consisted of two psychoeducation sessions on BPD: 1. Introduction; 2. Family Education; and four skills training modules: 3. Validation and acceptance skills. 4. Crisis management skills. 5. Problem management. 6. Relapse prevention. Table 1 describes the objectives and contents of each session in the two experimental conditions.

| Theme | Goals | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Family connections | ||

| Module 1: Introduction |

Introduction to the aims of the program and the guidelines, as well as brief information about BPD |

Commitment to participate in the program Information about the program and the guidelines Family members' rights Research on FC Symptoms and criteria of BPD Emotional Dysregulation Model by Linehan, 1993 Basic assumptions to be effective Videos and Homework |

| Module 2: Family education | Providing information on aspects related to BPD |

Updated information about BPD Treatment settings for BPD Types of treatment for BPD Comorbidity with other mental disorders Study of Expressed Emotions Biosocial Model of BPD Stigma Transactional Developmental Model of BPD and related disorders Videos and Homework |

| Module 3: Relationship mindfulness skills | Learning to be mindful with personal relationships and emotion regulation strategies |

Definition of a validating environment Education about Relationship Mindfulness “What” and “How” techniques States of mind Education about Emotions Emotion regulation strategies Decreasing emotional vulnerability and emotional reactivity Opposite Action strategy Videos and Homework |

| Module 4: Family environment skills | Understanding the relationship between individual and family well-being, as well as correcting maladaptive ways of thinking about blame |

Relationship between individual and family well-being The blame game Transactional process Dialectic tensions Basic assumptions to be effective Radical Acceptance. Videos and Homework |

| Module 5: Validation skills | Understanding what validation is and learning validation and self-validation skills. Also, an introduction to interpersonal efficacy |

Definition of validation Types of validation Validation aims Levels of validation Warning signs of invalidation Definition of self-invalidation Self-validating skills Observing your limits Interpersonal Efficacy DEAR MAN, GIVE, and FAST strategies Videos and Homework |

| Module 6: Problem management skills | Learning interpersonal efficacy strategies and problem management skills |

Finding the right time Definition of the “problem” 8 steps of problem management Chain analysis Goals to change something you did 3 steps to True Acceptance Videos and Homework |

| Treatment as usual | ||

| Module 1: Introduction | Providing an overview of the treatment and goals of the group as well as information on personality disorders, their clinical features, and comorbidity with BPD |

Definition and types of Personality Disorders Definition of BPD. Evolution of BPD Comorbidity with other mental disorders Information about alcohol and other drugs related to BPD |

| Module 2: Family education | Information about the biosocial model of emotion dysregulation and treatment for BPD |

Biosocial Model of Emotion Dysregulation by Linehan (1993) Types of treatment for BPD |

| Module 3: Validation | Understanding the difference between validating and invalidating environments |

Definition of an invalidating environment 5 key messages of validation |

| Module 4: Crisis management skills | Preventing crises by managing anger skills and learning how to manage self-injuring and suicidal behaviors |

Definition of crises. Anger management Education about self-injuring and suicidal behaviors Self-injuring and suicidal behavior skills |

| Module 5: Problem management | Learning problem management skills and setting limits |

Information about problem management of people with BPD Guide to confronting an unacceptable problem |

| Module 6: Relapse prevention | Strengthening the strategies learned throughout the program and preventing relapses |

Recall learned skills and resolve doubts Schedule future practice Teach the participants how to identify and cope with future high-risk situations |

Measurement and instruments

Caregivers and patients responded to a demographic questionnaire which includes relevant variables such as: age, genogram, sex, educational level, income, marital status, number / age of children, and psychiatric history.

Caregiver burden

Caregiver burden was measured with the Burden Assessment Scale (BAS; Horwitz & Reinhard, 1992) as translated and validated in Spanish (García-Alandete et al., 2023). This instrument is composed of 19 items that measure the objective and subjective burden of caregivers of people with illnesses in the past 6 months. Objective burden refers to the potentially observable behavioral effects of care in several areas, including financial problems, disrupted activities (limitations of personal activities, such as days lost at work), household disruption (alterations in family functioning), and social interactions (significant changes in work and social and family life). Subjective burden includes the feelings, attitudes, and emotions expressed about caregiving experiences. Personal distress refers to the sense of daily personal distress in managing the patient's condition. The time perspective refers to how the patient's illness influences the time perspective. It also includes guilt for not doing enough to help or even guilt for causing the illness. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 4 = a lot). Higher scores show higher levels of burden. Cronbach's alphas for our scores were 0.90 for the objective dimension, 0.87 for the subjective dimension, and for the subscales: Disruptive Activities (0.90), Personal Distress (0.84), Time Perspective (0.62), Guilt (0.79), and Basic Social Functioning (0.55); between 0.89 and 0.91, it has adequate validity.

Caregiver depression, anxiety, and stress

Caregiver distress was measured with the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21), a short version of the DASS-42 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) that has been validated in Spanish by Daza et al. (2002). The Depression scale assesses dysphoria, hopelessness, and anhedonia, among others. The Anxiety scale assesses autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, situational anxiety, and the subjective experience of anxious affect. The Stress scale is sensitive to levels of chronic non-specific arousal. It assesses difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, and being easily upset/agitated, irritable/over-reactive, and impatient. Responses are coded on a Likert scale (0 = It did not happen to me; 3 = It happened to me most of the time). Higher scores reflect higher levels of distress. DASS-21 shows excellent internal consistency in our sample: depression (α = 0.91), anxiety (α = 0.89), and stress (α = 0.90).

Caregiver quality of life

Caregiver quality of life was measured with the Multicultural Quality of Life Index (MQLI; Mezzich et al., 2000) validated in Spain by Mezzich et al. (2000). This 10-item questionnaire measures perceived quality of life (physical and emotional well-being, self-care and independent functioning, occupational and interpersonal functioning, social–emotional and community support, personal and spiritual fulfillment, and an overall perception of quality of life). Higher scores indicate higher quality of life. Answers are coded on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = bad, 10 = excellent). The internal consistency is good (Cronbach's alpha of 0.89), and test–retest reliability is high (r = 0.87). In our sample, the internal consistency was good (Cronbach's alpha of 0.91).

Caregiver family empowerment

The 34-item Family Empowerment Scale (FES; Koren et al., 1992) measures family empowerment and mastery (attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors) through three levels of empowerment: family, service system, and community. The family level measures empowerment within the family (I make efforts to learn new ways to help my child grow and develop). The service system measures the parents' efforts to advocate for and improve services for children and their families (I have a good understanding of the service system that my child is involved in.). The community measures family empowerment regarding the service system, and the family's involvement in the community (I feel I can have a part in improving services for children in my community). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all, 5 = very true), and higher scores indicate a greater feeling of empowerment. In our sample, internal consistency was: the family subscale (0.88), the service system subscale (0.87), and the community participation subscale (0.86). We used the Spanish validation by Fernández-Valero et al. (2020).

Patient distress

We used the same DASS-21 scale as with caregivers (Daza et al., 2002), which showed excellent internal consistency in our sample of patients: depression (α = 0.90), anxiety (α = 0.90), and stress (α = 0.86).

Patient perception of family support

The 15-item Lum Emotional Availability of Parents (LEAP; Lum & Phares, 2005) questionnaire measures the parental emotional availability as perceived by the person assessing their relatives. Sample items include “My parent supports me,” “My parent shows genuine interest in me”. Items are rated on a 6- point Likert scale (1 = never, 6 = always). The psychometric properties are very good, and for this clinical sample, excellent internal consistency is observed (for mother, α = 0.97, and for father, α = 0.98).

Patient perception of family validation

Validating and Invalidating Responses Scale (VIRS; Fruzzetti, 2007) is a 16-item scale that assesses the levels of perceived validation and invalidation in family members' responses, divided into two subscales (validating and invalidating responses). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = almost always). Higher scores indicate greater perceived validation or invalidation in the responses of the caregiver being assessed. In our sample, internal consistency ratings were validating responses subscale (α = 0.91) and invalidating responses subscale (α = 0.87).

Therapists and treatment fidelity

Eight clinical psychologists participated in this study. The therapists who participated in this study had at least a master's degree in clinical psychology and extensive experience in administering the DBT therapy for patients and the program that was routinely applied in the clinical center as support for family members (that is, the TAU condition). All the clinical psychologists applied both interventions indistinctly. In the clinical centers where the study was carried out, the clinical coordinator supervised the progress of all groups. For this purpose, weekly clinical sessions were held, and in these sessions any doubts about the application of the programs or the behaviors of the participants in the groups could be raised or clarified. Moreover, it should be noted that FC is a manualized treatment protocol, and to try to ensure adherence to Hoffman and Fruzzetti's FC protocol as much as possible, we established “common sessions” procedures, so that all the therapists delivered the same content (e.g., exercises, videos, homework) in each session.

Ethical considerations

For protection of data of study participants, this research followed the Declaration of Helsinki Guidelines and guidelines existing in both Spain and the European Union. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (Valencia, Spain). Data were collected by the investigators on this team, and identification data were replaced with codes. These data were separated from other data, and they were only available to the principal investigators of the study to protect the participants' confidentiality and privacy.

Statistical methods

Separate statistical analyses were performed for caregivers and patients. All analyses were carried out by applying Linear Mixed Models (LMMs). One advantage of applying LMMs is that participants with missing data at some time point (pretest, posttest, or follow-up) are not excluded from the analyses, thus preserving the initial sample size. For caregivers, due to the existence of statistical dependence between members of the same family, the family was included in all the analyses as a random factor. As a first step, with the purpose of checking whether the two groups were matched on all the outcomes on the pretest, LMM two-way ANOVAs were performed. The differential efficacy of FC and TAU was assessed by applying LMM two-way ANCOVAs, taking the pretest as a covariate, the two treatment groups as the main factor, the family as a random factor, and the posttest scores as the dependent variable. Due to the existence of missing data in the posttest, prior to the application of the LMM ANCOVAs, multiple imputation (MI) was used in order to impute missing data on the posttest. To assess the differential efficacy of FC and TAU in the follow-up, additional LMM two-way ANCOVAs were performed, taking the follow-up scores as the dependent variable. Due to the existence of a large percentage of missing data in the follow-up, LMMs were applied without previous imputation of missing data by means of MI (Jacobsen et al., 2017). To accomplish the objective of separately assessing the efficacy of each treatment from the pretest to the posttest for each group, LMM two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted, taking the measurement point (pretest vs. posttest) as the repeated measures factor, the family as a random factor, and each outcome as the dependent variable. Additional LMM one-way ANCOVAs were applied to assess the differential efficacy of the two treatments in the patients, taking the pretest as a covariate, the posttest as dependent variable, and the type of treatment as the main factor. In order to control the Type I error rate due to repeated statistical testing, probability levels were corrected by applying Benjamini and Hochberg's (1995) false discovery rate. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 28.

For both caregivers and patients, statistical significance tests were complemented by calculating effect sizes to assess the clinical significance of the findings. In particular, several versions of Cohen's d were applied. For comparisons of the two treatments, standardized mean differences were calculated, taking the means of the FC and TAU groups. To test the pretest-posttest improvements in each treatment group, standardized mean differences were calculated, taking the pretest and posttest means. For ANCOVAs, the standardized mean differences were calculated using the adjusted means of the FC and TAU groups. In all cases, d values of about 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 (in absolute values) were assessed as exhibiting small, moderate, and large effect size, respectively (Cohen, 1988). In the case of FC-TAU comparisons, positive d values indicated better performance of the FC group than the TAU group, and vice versa. For pretest-posttest comparisons, positive d values indicated better performance on the posttest than on the pretest, and vice versa.

RESULTS

The research team recruited 121 relatives and 82 BPD patients who met the eligibility criteria, signed the informed consent, and completed the baseline measures. The 121 relatives were randomized into one of the two study conditions (63 and 58 caregivers in FC and TAU, respectively) with dropouts in the posttest reaching 26.4% and 41.6% in the follow-up. The relatives corresponded to 82 patients, 41 from FC and 41 from TAU. Patient dropout on the pretest reached 18.3%, and so the statistical analyses were based on 67 patients (31 and 36 for FC and TAU, respectively).

Characteristics of study participants

Demographics and baseline characteristics of caregivers are shown in Table 2. There were not statistically significant differences were found in demographic characteristics between the relatives in the FC and TAU conditions (p > 0.05). Patient demographic characteristics are shown in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between the patients in the FC and TAU conditions (p > 0.05). In the same way, there were not statistically significant differences found between the two treatment groups on the pretest. The results are shown in Table S1.

| Variable | FC group | TAU group | Statistical test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary caregiver, n (%) | χ 2(1) = 0.14, p = 0.706 | ||

| Yes | 33 (70.2) | 31 (73.8) | |

| No | 14 (29.8) | 11 (26.2) | |

| Caregiver gender, n (%) | χ 2(1) = 0.33, p = 0.566 | ||

| Man | 13 (35.1) | 15 (41.7) | |

| Woman | 24 (64.9) | 21 (58.3) | |

| Caregiver occupation, n (%) | LR(6) = 3.88, p = 0.693 | ||

| Qualified job | 17 (45.9) | 21 (60) | |

| Non-qualified job | 7 (18.9) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Unemployed | 3 (8.1) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Retired | 7 (18.9) | 5 (14.3) | |

| Student | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Disabled | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Housekeeper | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Caregiver education, n (%) | LR(3) = 7.22, p = 0.065 | ||

| Primary | 6 (16.2) | 14 (38.9) | |

| Secondary | 11 (29.7) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Higher | 18 (48.6) | 15 (41.7) | |

| No studies | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Caregiver marital status, n (%) | LR(4) = 6.74, p = 0.150 | ||

| Single | 3 (8.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Couple | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Married | 25 (67.6) | 28 (77.8) | |

| Divorced | 8 (21.6) | 5 (13.9) | |

| Widowed | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Diagnosis axis I, n (%) | LR(4) = 3.33, p = 0.505 | ||

| No diagnosis | 26 (83.9) | 28 (84.4) | |

| Bipolar & related | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Depression | 2 (6.5) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Anxiety | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3) | |

| More than one | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Diagnosis axis II, n (%) | LR(4) = 4.52, p = 0.211 | ||

| No diagnosis | 27 (90) | 32 (100) | |

| Borderline | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Dependent | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | |

| More than one | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Interference with family a | 32.44 | 34.56 | U = 579.50, p = 0.647 |

| Age (years) b | 56.89 (10.50) | 56.69 (9.15) | t(71) = 0.089, p = 0.932 |

- Abbreviations: LR, likelihood ratio statistical test; t, independent t-test for comparing the means; U, independent-samples Mann–Whitney statistic; χ 2, statistic for testing differences between FC and TAU groups.

- a Values for FC (n = 63) and TAU (n = 58) groups are the mean ranks.

- b Values for FC and TAU groups are the means (and standard deviations).

| Variable | FC group | TAU group | Statistical test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient gender, n (%) | χ 2 (1) = 0.97, p = 0.324 | ||

| Man | 4 (13.3) | 8 (22.9) | |

| Woman | 26 (86.7) | 27 (77.1) | |

| Patient occupation, n (%) | |||

| Qualified job | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | LR(4) = 8.52, p = 0.074 |

| Non-qualified | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Job Unemployed | 1 (7.7) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Student | 6 (46.2) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Disabled | 4 (30.8) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Patient education, n (%) | LR(3) = 2.89, p = 0.408 | ||

| Primary | 3 (23.1) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Secondary | 6 (46.2) | 9 (60) | |

| Higher | 4 (30.8) | 4 (26.7) | |

| No studies | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Patient marital status, n (%) | LR(2) = 4.01, p = 0.135 | ||

| Single | 9 (69.2) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Couple | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Married | 2 (15.4) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Diagnosis Axis I, n (%) | LR(7) = 5.54, p = 0.594 | ||

| No diagnosis | 9 (56.3) | 10 (47.6) | |

| Schizophrenia & related | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Bipolar & related | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Depression | 1 (6.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Trauma & stress | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Eating disorders | 1 (6.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Substances | 1 (6.3) | 1 (4.8) | |

| More than one | 2 (12.5) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Diagnosis Axis II, n (%) | LR(1) = 2.51, p = 0.113 | ||

| BPD | 16 (80) | 21 (95.5) | |

| More than one | 4 (20) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Diagnosis cluster, n (%) | LR(1) = 2.51, p = 0.113 | ||

| BPD | 16 (80) | 21 (95.5) | |

| Cluster B | 4 (20) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Toxic substance use, n (%) | LR(1) = 0.31, p = 0.580 | ||

| Yes | 3 (21.4) | 4 (30.8) | |

| No | 11 (78.6) | 9 (69.2) | |

| Hospital admissions a | 12/1.25/1.49 | 12/2.00/2.99 | t(22) = −0.78, p = 0.444 |

| Suicide attempts a | 8/5.25/10.17 | 12/2.42/3.06 | t(18) = 0.92, p = 0.372 |

| Self-injury last year a | 8/2.88/2.90 | 12/6.75/12.05 | t(18) = −0.89, p = 0.388 |

| Age (years) a | 31/29.9/12.1 | 36/28.2/11.1 | t(65) = 0.58, p = 0.565 |

- Note: Sample sizes for FC and TAU = 31 and 36, respectively.

- Abbreviations: LR, likelihood ratio statistical test for comparing FC and TAU groups; t, independent t-test for comparing means; χ 2, Chi-squared statistic.

- a Values for FC and TAU groups are sample size/mean/standard deviation.

Differential efficacy of FC versus TAU on caregivers

An objective of this RCT was to assess the differential efficacy of the FC and TAU conditions in the caregivers in the posttest and follow-up. The results are shown in Table 4. No statistically significant differences were found between FC and TAU on any of the BAS, DASS-21, FES, and MQLI subscales. However, it is worth noting that, except for MQLI and DASS-21 Anxiety, adjusted posttest means for FC were systematically better than for TAU, with effect sizes (adjusted Cohen's ds) ranging between 0.20 (DASS-21 Stress and Depression) and 0.50 (FES Family).

| FC | TAU | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Meanadj | SE adj | Meanadj | SE adj | F | p fdr | Cohen's d adj |

| BAS | |||||||

| Objective dimension | 1.97 | 0.11 | 2.31 | 0.10 | 4.91 | 0.159 | 0.40 |

| Subjective dimension | 1.91 | 0.09 | 2.16 | 0.10 | 3.47 | 0.179 | 0.34 |

| Disrupted activities | 2.02 | 0.13 | 2.41 | 0.13 | 4.63 | 0.159 | 0.39 |

| Personal distress | 1.53 | 0.11 | 1.76 | 0.12 | 1.55 | 0.316 | 0.23 |

| Time perspective | 2.39 | 0.12 | 2.65 | 0.11 | 2.86 | 0.212 | 0.31 |

| Guilt | 1.82 | 0.12 | 2.07 | 0.14 | 1.84 | 0.278 | 0.25 |

| Basic social functioning | 1.91 | 0.13 | 2.20 | 0.11 | 2.54 | 0.246 | 0.29 |

| DASS-21 | |||||||

| Stress | 0.60 | 0.09 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 1.22 | 0.321 | 0.20 |

| Depression | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 1.21 | 0.321 | 0.20 |

| Anxiety | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.774 | 0.05 |

| FES | |||||||

| Family | 45.86 | 1.06 | 41.64 | 1.32 | 7.62 | 0.098 | 0.50 |

| Service system | 42.84 | 1.24 | 39.65 | 1.27 | 3.82 | 0.179 | 0.36 |

| Communication/political | 27.70 | 1.15 | 25.11 | 1.37 | 2.09 | 0.273 | 0.26 |

|

MQLI |

71.64 |

2.21 |

73.15 |

1.99 |

0.28 |

0.642 |

−0.10 |

- Note: These results were based on intent-to-treat analyses consisting of applying multiple imputation to impute missing data previous to the application of LMMs. Sample sizes for FC and TAU groups were 63 and 58, respectively. Cohen's d adj was calculated by means of: .

- Abbreviations: Cohen's d adj , adjusted standardized mean difference between FC and TAU groups on the posttest adjusted by the pretest; F, LMM ANCOVA F-statistic for testing the statistical significance between FC and TAU groups on the posttest taking the pretest as covariate; FC, Family Connections group; p fdr , probability level of the t statistic adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg's (1995) false discovery rate; Positive d adj values indicated a better level for the FC group than TAU on the posttest; and vice versa; SE, standard error of the mean; TAU, treatment as usual group.

Regarding the comparison of FC and TAU at the follow-up, due to the large percentage of dropouts, multiple imputation was not used, but LMMs were directly performed. The results are presented in Table 5. There are statistically significant differences in favor of FC condition were only found for the three subscales of the FES, with large effect sizes (adjusted Cohen's ds between 0.84 and 1.26). Due to the high attrition in the follow-up, these results must be interpreted with caution.

| FC | TAU | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Meanadj | SE adj | Meanadj | SE adj | F | p fdr | Cohen's d adj |

| BAS | |||||||

| Objective dimension | 1.56 | 0.16 | 1.96 | 0.22 | 2.20 | 0.190 | 0.40 |

| Subjective dimension | 1.60 | 0.15 | 2.03 | 0.20 | 2.84 | 0.160 | 0.45 |

| Disrupted activities | 1.58 | 0.18 | 2.11 | 0.23 | 3.30 | 0.140 | 0.49 |

| Personal distress | 1.26 | 0.15 | 1.83 | 0.20 | 5.07 | 0.095 | 0.69 |

| Time perspective | 1.99 | 0.19 | 2.21 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.476 | 0.19 |

| Guilt | 1.58 | 0.19 | 2.00 | 0.25 | 1.77 | 0.226 | 0.36 |

| Basic social functioning | 1.52 | 0.17 | 1.84 | 0.22 | 1.28 | 0.290 | 0.32 |

| DASS-21 | |||||||

| Stress | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 4.01 | 0.128 | 0.54 |

| Depression | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 2.25 | 0.190 | 0.41 |

| Anxiety | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 5.60 | 0.091 | 0.70 |

| FES | |||||||

| Family | 49.81 | 1.36 | 39.49 | 1.85 | 20.06 | 0.007 | 1.26 |

| Service system | 45.71 | 1.43 | 38.27 | 1.90 | 9.81 | 0.019 | 0.84 |

| Communication/political | 31.62 | 1.24 | 23.36 | 1.68 | 15.23 | 0.007 | 1.04 |

| MQLI | 76.75 | 2.46 | 68.69 | 3.30 | 3.92 | 0.128 | 0.55 |

- Note: These results were based on intent-to-treat analyses consisting of in to apply linear mixed models but without applying multiple imputation due to the large number of missing data in the follow-up. Sample sizes for FC and TAU groups were 58 and 63, respectively.

- Abbreviations: Cohen's d adj , adjusted standardized mean difference between FC and TAU groups in the follow-up; F, LMM ANCOVA F-statistic for testing the statistical significance between FC and TAU groups in the follow-up; FC, Family connections group; M adj, adjusted means in the follow-up by the pretest; p fdr , probability level of the t statistic adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg's (1995) false discovery rate; Positive d adj values indicated a better level for the FC group in the follow-up; and vice versa; SE adj, adjusted standard error of the mean; TAU, treatment as usual group.

Pretreatment to posttreatment changes in caregivers

A second objective was to assess the efficacy of the two active treatments separately. The results are shown in Table 6. In the FC condition, statistically significant improvements were found from the pretest to the posttest on Objective Dimension (d = 0.31), the Subjective Dimension (d = 0.47), Disrupted Activities (d = 0.36), the Time Perspective (d = 0.39), and Guilt (d = 0.37). Significant improvements were also found on the DASS-21 for Stress (d = 0.41), Depression (d = 0.29), and Anxiety (d = 0.27), as well as quality of life (MQLI, d = 0.28), and on the FES for Family (d = 0.58), Service System (d = 0.39), and Communication/Political (d = 0.49). In the TAU condition, as Table 6 shows, statistically significant improvements were found only in quality of life (d = 0.45).

| Pretest-posttest change for FC | Pretest-posttest change for TAU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | t | p fdr | d | t | p fdr | d |

| BAS | ||||||

| Objective dimension | 2.50 | 0.022 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.922 | 0.02 |

| Subjective dimension | 3.75 | 0.004 | 0.47 | 1.15 | 0.478 | 0.15 |

| Disrupted activities | 2.82 | 0.012 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.922 | 0.04 |

| Personal distress | 1.68 | 0.113 | 0.21 | 0.57 | 0.798 | 0.07 |

| Time perspective | 3.12 | 0.006 | 0.39 | 1.48 | 0.390 | 0.19 |

| Guilt | 2.91 | 0.008 | 0.37 | 0.83 | 0.639 | 0.11 |

| Basic social functioning | 1.44 | 0.159 | 0.18 | −0.10 | 0.922 | −0.01 |

| DASS-21 | ||||||

| Stress | 3.27 | 0.004 | 0.41 | 1.40 | 0.390 | 0.18 |

| Depression | 2.33 | 0.028 | 0.29 | 1.62 | 0.390 | 0.21 |

| Anxiety | 2.12 | 0.060 | 0.27 | 1.59 | 0.390 | 0.21 |

| FES | ||||||

| Family | 4.60 | 0.004 | 0.58 | 1.12 | 0.478 | 0.15 |

| Service system | 3.10 | 0.007 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.922 | 0.03 |

| Communication/political | 3.85 | 0.004 | 0.49 | 1.70 | 0.390 | 0.22 |

| MQLI | 2.24 | 0.038 | 0.28 | 3.42 | 0.014 | 0.45 |

- Note: Sample sizes for the FC and TAU groups were 63 and 58, respectively. Cohen's ds were calculated by means of: .

- Abbreviations: d, Cohen's d for within-group pretest-posttest change scores; FC, Family Connections group; p fdr , probability level of the t statistic adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg's (1995) false discovery rate; t, LMM t-statistic for testing the statistical significance of the pretest-posttest change scores for each group; TAU, Treatment As Usual group.

Effects on patients

A third objective was to examine the differential efficacy of the FC and TAU conditions received by the relatives in their BPD patients. The results are shown in Table 7. None of the outcomes assessed showed statistically significant differences between FC and TAU on the posttest adjusted means. However, there were clinically relevant effect sizes in favor of FC on Stress (d = 0.41), Depression (d = 0.41), and Anxiety (d = 0.47).

| FC group | TAU group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | M adj | SD adj | M adj | SD adj | F | p | d adj |

| DASS-21 | |||||||

| Stress | 1.33 | 0.16 | 1.70 | 0.15 | 2.81 | 0.103 | 0.41 |

| Depression | 1.20 | 0.18 | 1.62 | 0.17 | 2.75 | 0.107 | 0.41 |

| Anxiety | 0.93 | 0.15 | 1.32 | 0.14 | 3.60 | 0.067 | 0.47 |

| LEAP | |||||||

| Mother | 63.96 | 4.32 | 61.56 | 4.05 | 0.16 | 0.690 | 0.11 |

| Father | 52.37 | 3.79 | 54.61 | 3.41 | 0.19 | 0.665 | 0.12 |

| VIRS | |||||||

| Validating | 32.14 | 1.58 | 30.62 | 1.40 | 0.51 | 0.479 | 0.18 |

| Invalidating | 6.01 | 0.76 | 5.70 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.766 | 0.08 |

- Note: Positive d adj values indicated a better level for the FC group in the posttest; and vice versa. These results were based on intent-to-treat analyses consisting in to apply linear mixed models but without applying multiple imputation. Sample sizes for FC and TAU groups were 31 and 36.

- Abbreviations: Cohen's d adj, adjusted standardized mean difference between FC and TAU groups in the posttest; F, LMM ANCOVA F-statistic for testing the statistical significance between FC and TAU groups in the posttest; FC, Family Connections group; Madj, adjusted means in the posttest by the pretest; SE adj, adjusted standard error of the mean; TAU, treatment as usual group.

The results regarding the evolution of the patients from pre-test to post-test in the two experimental conditions are presented in Table S2. Regarding patients of caregivers receiving the FC condition, after adjusting the p values by means of the false discovery rate, statistically significant improvements from the pretest to the posttest were found for Stress (d = 0.55), Depression (d = 0.50), and Anxiety (d = 0.64) in the FC condition. In patients of caregivers that received the TAU condition, no statistically significant improvements were found.

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of this RCT was to assess the differential efficacy of FC, compared to TAU, in reducing burden, stress, anxiety, and depression, and improving family mastery empowerment and emotional attention, in relatives of BPD patients. The results indicate that at posttreatment there were no statistically significant differences between the two experimental conditions in any of the primary and secondary measures; however, at 6-month follow-up, the FC condition performed better than the TAU condition in the family domain and empowerment in the FES subscales (Family, Service System and Communication/Policy). Therefore, in terms of statistical significance, our hypothesis of a better result for FC than for TAU was not confirmed. However, it is worth noting that most of the outcomes exhibited clinically significant effect sizes in favor of FC on the posttest, with Cohen's ds ranging between 0.20 and 0.50. In the follow-up, effect sizes also ranged from moderate to large (from 0.32 to 1.26). We believe that one possible reason for not finding statistical significance was low statistical power. As described in the Method section, our a priori sample size determination assumed an effect size of d = 0.60. However, none of our results on the posttest achieved such a large Cohen's d. The effect sizes larger than 0.60 obtained in the follow-up did not reach statistical significance because the p values were adjusted by means of Benjamini and Hochberg's (1995) false discovery rate. Therefore, although our results did not confirm our hypothesis of differential efficacy in favor of FC, the magnitude of the effect sizes obtained in favor of FC warrants future research with a large sample size to clearly determine the possible differential efficacy of FC versus TAU.

Moreover, it should be noted that both experimental conditions share many elements in common. Both offer psychoeducation and training in different DBT skills, and both have a similar duration. In addition, both conditions are based on the biosocial model and share some of the skills such as interpersonal validation and acceptance. However, the TAU intervention also includes some CBT-based components. Therefore, it is possible that the non-significant results between conditions may be due to the high degree of overlap between the two conditions combined with the low statistical power. In this regard, it should be noted that our purpose was to compare the effects of the FC program with the intervention program to support family members that was routinely applied in this specialized BPD treatment center prior to learning about the FC program. Perhaps these results indicate that this earlier intervention was quite effective, although this does not mean that it cannot be improved, as indeed we believe to be the case with what the FC program provides.

To the best of our knowledge, to date, the only study that has compared FC with another active condition is the Flynn study (Flynn et al., 2017). The aim of this study was to compare the 12-week FC program to a three-week optimized treatment-as-usual (OTAU) program. This study was a non-randomized controlled study with assessments of outcomes at pre- and post-intervention and follow-up (3 and 12- or 19-months post-intervention). The FC intervention was effective in improving subjective and objective burden and grief. The OTAU group showed changes in the same direction but none of the changes were statistically significant. Improvements were maintained at follow-up in FC participants. The lack of significant changes on all the measures for OTAU suggests that a three-session psycho-education program applied in Flynn et al. (2017) was of limited benefit. Further research is warranted on program components and long-term support for family members. In our study, the control intervention consisted of the same number of sessions as the FC condition (12 sessions).

A second objective was to separately assess the efficacy of each intervention in the caregivers from the pretest to the posttest. The participants that received FC intervention improved in five of the seven dimensions of the BAS: Objective Dimension, Subjective Dimension, Disrupted Activities, Time Perspective, and Guilt, as well as on Stress, Depression, Family, Service System, Communication/Political, and quality of life. In the TAU intervention, improvements were only found for quality of life. Therefore, our hypothesis about the effect of interventions was confirmed for the FC condition, but not for TAU. However, it is important to interpret these findings with caution because the pretest-posttest comparisons for each intervention were not based on the original design of this study (an RCT).

These results are in line with those obtained in previous studies. The effectiveness of the FC program for family members of individuals with a BPD diagnosis was initially explored by Hoffman et al. (Hoffman et al., 2005), where 44 participants completed pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up. In 2007, the authors carried out a replication study with a larger population sample (N = 44; Hoffman & Fruzzetti, 2007). Both studies found that participation in the FC program led to significant reductions in grief, burden, and depression and to improvements in mastery levels. In Sweden, a nine-session FC program was adapted to help family members of individuals who had attempted suicide (Rajalin et al., 2009), and the results showed a reduction in depression and burden scores was also observed.

FC interventions have also been studied, depending on the delivery format; for example, Liljedahl et al. (2019) compared outcomes of the 12-week FC program to outcomes of a two-weekend intensive FC program. They did not find significant differences between the two types of FC programs; overall, a significant reduction in burden, a significant improvement in overall mental wellbeing, and an improvement in family functioning were observed in both types of FC. These improvements were sustained at six to seven months post-FC. Recently, Guillén et al. (2022) explored the efficacy of FC administered online versus face-to-face in 45 relatives of people diagnosed with personality disorder in a non-randomized pilot study with pre-post assessments. The results showed statistically significant improvements in burden, depression, anxiety, and stress, family empowerment, family functioning, and quality of life. There were no differences based on the delivery format. Thus, this study provides relevant data about the possibility of implementing FC in an online format without losing its effectiveness.

A third objective was to assess the differential effect of FC compared to TAU in BPD patients whose relatives had received the intervention. Our hypothesis of greater benefits in patients whose relatives received the FC condition in comparison with those who received the TAU condition was not confirmed, although stress, depression, and anxiety outcomes of the patients exhibited moderate effect sizes in favor of FC. Therefore, our results show a trend in favor of FC, but not a conclusive one. So far, to our knowledge, no other study has been published on the possible impact of relatives receiving FC on the patients themselves.

Adherence to treatment in relatives of people with severe mental disorders (Pearce et al., 2017) is a problem in psychological interventions. In our study, dropouts at post-treatment (26.4%) were similar to other studies that reported dropout rates of around 29% (Flynn et al., 2017; Pearce et al., 2017; Rajalin et al., 2009). In the same vein, in our study, dropouts at follow-up (41.6%) were like those found by Flynn, who reported that 46% completed long-term follow-up measures. This may be explained by compliance (or not) with expectations, participants' motivation at the start of the intervention, time availability, illness awareness, or active components of the program. These issues require further study.

In summary, this is the first study to evaluate relatives and patients in an RCT design comparing two active treatment conditions of similar durations. The results show improvements in burden, stress, depression, family functioning, and quality of life in the family members in the FC intervention. In patients of caregivers who received the FC condition, statistically significant improvements in Stress, Depression, and Anxiety were found from pretest to posttest. This work contributes to the advancement of evidence-based clinical psychology that can ultimately contribute to the well-being of patients and their families.

Our study has several limitations. One limitation is the loss of data, especially at follow-ups. Although we performed intent-to-treat analyses based on the application of LMMs and multiple imputation techniques, the attrition at the posttest, and especially at the follow-up, seriously limits the generalizability of the results. Another limitation is that the pretest-posttest comparisons separately carried out to assess the efficacy of each intervention were not based on the original experimental design, which limits the validity of their results. Another limitation is the impossibility of ensuring full functional and scalar equivalence for the Spanish-language measures used in this study, and it should be noted that no objective measures of treatment fidelity were used. Finally, most of the BPD patients were treated in clinical settings, which may affect the results. In addition, the collection of post-treatment evaluation data from patients was quite difficult because they were not involved in the implementation of the interventions directly (either FC or TAU), only family members were involved, and patients may not have felt as involved in completing post-treatment or follow-up evaluations.

Further studies with methodologically rigorous designs are needed to draw firmer conclusions about their results. These studies should be carried out with larger samples to ensure adequate statistical power and with long-term follow-ups to verify the stability of the results obtained. It would also be of great interest to compare interventions applied by family members with interventions carried out by clinicians, as they would give us useful information about how to plan the formation of the groups, or about the supervision and training of clinicians and family members. These new studies on FC with relatives of people with BPD and other pathologies should also focus on more specific measurement instruments and the specific skills taught in the program.

In conclusion, our study contributes to the literature on the care and support that needs to be provided to family members of patients with BPD by evaluating the efficacy of the FC program through a randomized controlled clinical trial, conducted in a Spanish-speaking sample. We believe that such interventions should be considered to improve the holistic approach to the treatment of people with severe psychological disorders. In any case, much remains to be done; this line of work has only just begun.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We want to thank the National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder Spain (NEABPD-SPAIN), the Valencian Association of Personality Disorders (ASVA TP), and ITA Salut Mental, for their collaboration in this study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding for the study was provided by (R + D + I) Consellería de Innvoación, Universidades, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital: R&D&I projects developed by Emerging groups. Code: GV/2019. This funding source had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit the results.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study follows the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and existing guidelines in Spain and the European Union for the protection of patients in clinical trials. All participants interested in participating signed an informed consent form. The Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (Valencia, Spain) approved this study H1520331909767. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrial. gov ID: NCT04160871.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.