The family alliance as a facilitator of therapeutic change in systemic relational psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A case study

Methods based on the original work of Escudero and Friedlander ( 2017) multidimensional System of Observing Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA), the original work of Campo and D'Ascenzo ( 2010) integrated individual and family treatment for Borderline Personality Disorders and the semi-structured clinical interviews created by D'Ascenzo ( 2021) to assess therapeutic change. Team members who participated were Veronica Zurdo, Sonia Torras, Dr. Anna Vilaregut, Dr. Ignacio Bolaños, and Dr. Iolanda D'Ascenzo.

The analysis of family alliance was carried out by Veronica Zurdo and Sonia Torras directed by Anna Vilaregut, Iolanda D'Ascenzo, and Ignacio Bolaños. The analysis of therapeutic change was carried out by Anna Vilaregut and Iolanda D'Ascenzo, and subsequently it was agreed upon with the rest of the team members.

Abstract

Managing the Therapeutic Alliance is often complex when it comes to the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD), but the alliance is crucial for the success of the therapy. Combined individual and family interventions have been shown to be very useful in treating of these cases. This study has two objectives. First, to describe how the family therapeutic alliance facilitates therapeutic change through family psychotherapy for families with a member diagnosed with BPD. Second, to analyze how the therapeutic change achieved through combined individual and family systemic relational psychotherapy affects the individual functioning of the patient with BPD. This single case study used the System of Observation of Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA-o) to analyze the therapeutic alliance, along with two semi-structured clinical interviews, one at the beginning and one at the end of therapy. Results show a dynamic and positive evolution of the therapeutic alliance throughout the therapeutic process and how this alliance facilitated therapeutic change, both reducing the symptomatology of the patient with BPD and improving family communication and functioning. Results contribute to highlighting the importance of including family therapy as an intervention unit in protocols for patients with BPD.

Managing the therapeutic alliance with people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) can be difficult. The very characteristics of the disorder itself bring with them a degree of instability in interpersonal functioning that can make it hard to forge and maintain a successful alliance (Jeung & Herpertz, 2014; Lazarus et al., 2014; Waldinger & Gunderson, 1984). As Cash et al. (2014) and McMain et al. (2015) have observed, therapists' relations with these patients are marked by volatility. Patients can swing back and forth between idealizing and denigrating the therapist, and ruptures in the therapeutic alliance are common and difficult to repair. Studies have shown that a strong therapeutic alliance with BPD patients is associated with greater adherence to treatment and better outcomes. The relationship with the therapist can become a model for future relationships (Hirsh et al., 2012; Spinhoven et al., 2007).

Within individual therapeutic approaches such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Cognitive Analytic Therapy (Bennett et al., 2006; Gersh et al., 2017), there have been efforts to pay special attention to ruptures in the therapeutic alliance that often emerge with BPD patients. A greater number of ruptures during the initial therapy sessions is associated with poor therapy outcomes (Anderson et al., 2016).

Other approaches that feature a combination of individual and family interventions have been shown to be very useful in the treatment of personality disorders. A number of studies have highlighted the central role played by the family in therapy for BPD and have analyzed the effectiveness of family therapy in these cases (Allen, 2001; Cancrini & De Gregorio, 2018; Choi, 2018; Giffin, 2008; Glick et al., 1995; Infurna et al., 2016; Woodberry et al., 2002).

The earliest studies to include the family in BPD treatment were psychoeducational and were based on the idea that family therapy seems to lead to better results for people with this disorder (Hooley & Hoffman, 1999). One noteworthy example was a therapeutic approach called Family Connections (Fruzzetti & Hoffman, 2004; Hoffman et al., 2003), which involved offering support and training to families in order to help them develop skills to validate the person with BPD. Another significant mixed approach is based on the work of Linehan (2003), who underlines the issue of the lack of emotional validation in families with a member with BPD. Consequently, this approach takes the family into account by integrating certain ideas from systemic psychotherapy into the etiology of BPD, which is thought to emerge from the interaction between individual emotional vulnerability and family and social context. Systems treatments for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS) take a similar path by including professionals, family, and friends in the treatment to help shed light on the emotional and behavioral control problems faced by people with BPD in order to offer guidelines for improvement (Blum et al., 2008).

The systemic relational model views the family and/or other significant relationships as the preeminent setting for the development and functioning of the individual, and, as such, includes these factors in both diagnosis and therapy. In other words, this model goes beyond merely involving the family in the therapeutic process as happens in the psychoeducational approach. Here, the family and other significant relationships are the focus of interest, both as a gateway to an understanding of the disorder based on relational psychopathology and as elements of therapeutic process, as well as playing a key role in consolidation of changes aimed at modifying the functioning of the patient's personality (Allen, 2001; Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010; Cancrini & De Gregorio, 2018; D'Ascenzo, 2021; D'Ascenzo & Sciarillo, 2012; Selvini, 2008).

Using a systemic approach, Campo and D'Ascenzo (2010) have argued that working directly with patients' social network rather than just with a symbolic network is more effective and time efficient. They propose an intervention model based on a combination of individual and family sessions, designed to create synergy to fuel and consolidate therapeutic change. Including family members and other significant figures from the start of the process allows the therapist to more reliably diagnose the patient's relationships and the functioning, structure, and organization of his or her family. Such an approach also investigates family history and child rearing. These researchers suggest that intervening with the family helps give meaning to the past and present behaviors, feelings, and thoughts of all family members, and that such interventions are able to influence behaviors and personality traits through these significant relationships (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010; D'Ascenzo, 2021; D'Ascenzo et al., 2023).

In short, according to D'Ascenzo et al. (2019, 2023), building solid alliances with individuals and their families is important for the success of the therapeutic process for BPD. However, involving the family makes for a more complex therapeutic relationship than one where the alliance is only with the individual patient.

A review of the literature shows that the systemic model is able to address the complexities of the therapeutic alliance in family therapy. The systemic approach views this alliance as the result of an interaction between the patient's system and the therapist's system, the latter including the therapeutic team and supervisor (Mateu et al., 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to have strong ties with all the members of the family unit, whether or not they attend therapy sessions, and it is critical that the therapist plays an active role in the construction of the alliance in order to help strike a balance among all the members of the family and to facilitate cooperation (D'Ascenzo et al., 2023; Perkins et al., 2019).

Research has shown that a strong alliance can facilitate therapeutic change in the context of family therapy (Escudero et al., 2008; Glazer et al., 2003). Lambert et al. (2012) added that, in family therapy, the alliance should go beyond the link between the therapist and the patient to encompass the relations among all the members of the family, these relationships can play a decisive role. These researchers borrow the concept of the intra-system alliance from Pinsof and Catherall (1986). This term is defined as a shared sense of purpose in the family. It involves a certain degree of agreement as to the nature of the problems to be treated and a shared perspective on treatment goals, and it places value on working together in the therapeutic setting (Friedlander et al., 2006, 2008).

In a recent meta-analysis of 48 studies, Friedlander et al. (2018) confirmed the important role the alliance plays in facilitating change in family therapy. The analysis showed significant correlations between the alliances formed both with the therapist and among the family members and the success of therapy, defined in terms of intermediate and final results and the level of adherence to treatment. These researchers also underline the importance of calling attention to the strength of the intra-system alliance by working with families to identify shared feelings and experiences and by validating shared suffering. Such practices can help ensure commitment and adherence to treatment and can improve outcomes. The study recommends interventions based on safety and emotional connection to improve the alliance and reinforce individual commitment.

Links have also been found between the strength of the alliance and symptomatic change over the course of multiple sessions. That is why it is considered essential to analyze the alliance over at least four different sessions (Crits-Christoph et al., 2011). Some studies have shown that an improved alliance in one session is tied to improvements in symptoms in the following sessions, while a deterioration in symptoms can sometimes be the result of an unfavorable alliance. In other words, there can be a bidirectional influence between the alliance and symptoms throughout treatment (Falkenström et al., 2013; Tasca & Lampard, 2012;).

The therapist plays an essential role in the development of the alliance. Friedlander et al. (2006) found that therapists are more effective when they are able to create an emotional connection with the patient in spite of the potential differences between them. Additionally, according to Escudero et al. (2008), the first meeting of the therapist and the family is a decisive moment. Patients tend to be concerned about and interested in how the other members of the family explain their perspectives on the problem. This is even more complex in families where communication is lacking or dysfunctional. Therefore, it is a crucial precondition for family therapy that the therapist creates a safe setting.

The growing scientific and clinical interest in the therapeutic alliance has led to the development of a range of instruments designed to assess this relationship. One of the most prominent of these tools is the System for Observing Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA-o; Escudero & Friedlander, 2003; Friedlander et al., 2005), whose aim is to measure the therapeutic alliance within the family system. This instrument conceptualizes the therapeutic alliance as a function of four interlocking dimensions that apply to both the clients and the therapist: Engagement in the Therapeutic Process, Emotional Connection to the Therapist, Safety within the Therapeutic System, and a Shared Sense of Purpose within the Family. The four dimensions are independent of one another, but they are not mutually exclusive, meaning that correlations among them are to be expected in the analysis (Friedlander et al., 2006).

Most of the studies using the SOFTA-o have focused on couple therapy. Their findings have highlighted that the construction of the alliance is a dynamic process and that the dimensions most linked to the viability of the therapeutic process and to better prognoses for couple therapy are Safety and Shared Purpose (Pinsof & Wynne, 2000). Studies of couple therapy when one member of the couple suffers from major depression have concluded that the Shared Purpose dimension can be decisive as to whether patients see improvements in their depressive symptomatology (Artigas et al., 2017; Mateu, 2015; Vilaregut et al., 2018). In family therapy, studies have found that the strength of the intrasystem alliance and other elements of the alliance have a stronger correlation than other aspects of the alliance with the outcomes of therapy (Friedlander et al., 2018).

Based on the assumption that the family alliance supports the therapeutic process in cases of BPD, D'Ascenzo et al. (2019) conducted the first study using the instrument SOFTA-o to analyze the construction of the alliance in the initial phase of a process of systemic relational psychotherapy to treat this disorder. They found that the dimensions Emotional Connection and Safety were the most influential in forming and consolidating the therapeutic alliance. When parents of patients were invited to sessions without the patient, they tended to feel safer, more at ease, and more involved in the therapeutic process. Meanwhile, the individual sessions held with the patient were especially effective in contributing to the Emotional Connection between the patient and the therapist. The study also showed that Engagement was the most affected by the interventions of the therapist, while Shared Purpose often began with poor scores but tended to evolve positively throughout the therapeutic process. These results were confirmed in a study by D'Ascenzo et al. (2023) that analyzed the construction and the evolution of the therapeutic alliance throughout the therapeutic process, one that combined individual and family sessions following the model of integrating individual and family treatment of Campo and D'Ascenzo (2010) and D'Ascenzo (2021).

In light of these considerations, the main objectives of this study are twofold. First, to describe how the family therapeutic alliance facilitates therapeutic change by analyzing the most frequent and significant indicators that appear during the family psychotherapy treatment of a family with a member diagnosed with BPD. Second, to analyze how the therapeutic change achieved through the integrated individual and family treatment model (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010; D'Ascenzo, 2021) affects the individual functioning of the patient with BPD.

METHOD

Design

This is a single case study, using an indirect, semi-structured observational method. The aim is to contribute to the knowledge of the functioning of the alliance throughout the therapeutic process in systemic relational family psychotherapy for a family with a member diagnosed with BPD, as prior research has suggested analyzing the small-scale interpersonal events that occur in therapy (Horvath, 2011). Studies that use this type of methodology select representative examples of phenomena in order to study them exhaustively and in-depth (Martínez-Arias et al., 2014), thereby establishing a link between research and clinical practice (García & Cáceres, 2014; Roussos, 2007). In order to assess therapeutic change and the patient's personality functioning, this study uses a qualitative method based on the principles of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

Participants

The family has five members. The original names have been replaced with pseudonymous. Carmen, 61 years old, was a preschool teacher. Pedro, 62 years old, was a primary school teacher but retired early. The couple had three daughters. Victoria, 37, a surgeon who was married and had a son. Alejandra, 32, a nurse who was also married and had a son. Manuela, 27, was a nurse's aide and had been with her partner for 3 years. Manuela resided with her parents at the time of the interview. They came to seek treatment at the Family Therapy Service of Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona. The youngest daughter, Manuela, was diagnosed with BPD and Major Depressive Disorder by the psychiatric service of another hospital, where she received individual treatment. The prevalence of affective disorders among patients with BPD have been found to range between 40% and 97%, and Major Depressive Disorder is the most common diagnosis (Zanarini et al., 1998). The family were referred to the service by the psychiatrist who was treating the mother. She had depressive symptoms and was on medical leave from her job. In the family therapy request form filled out by the family, the request was focused on family relations and communication problems, particularly with regard to the youngest daughter, Manuela. Both Manuela and her parents said that she led a “double life” and deceived everyone. When she was 12–13 years old, she began this pattern of deception, a series of behaviors that intensified to the degree that, at age 18, she was stealing from her parents. Manuela misspent the money intended for her university tuition and took out loans from banks, which she was incapable of repaying. Early in their daughter's adolescence, Manuela's parents consulted a psychologist, and since then she had received treatment based on individual approaches but had not seen improvements. Her behavioral, emotional, and relationship problems increased, and they interfered with her individuation process to the extent of crystallizing into a personality disorder.

The therapy was carried out by two psychologists enrolled in the master's program in Systemic Family Therapy at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau. The team of therapists was made up of a therapist and a co-therapist, both 28 years old, who had, respectively, 6 and 5 years of experience in the field of family psychotherapy. The supervisor was a psychiatrist specializing in Relational Family Psychotherapy with 30 years of experience in the field.

Instruments

To evaluate the therapeutic alliance, the System for Observation of Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA-o, Friedlander et al., 2006) was used. It consists of four dimensions: Engagement in the Therapeutic Process, the degree to which the client is involved in the therapeutic process; Emotional Connection, the degree to which the client views the relationship with their therapist as based on interest, trust, and a sense of belonging; Safety within the Therapeutic System measures the degree to which the client sees therapy as a space where he or she can take risks, be flexible and open to new experiences; and Shared Sense of Purpose assesses whether family members view themselves as working together to improve their relationships and achieve common goals. It has two distinct parts, which together evaluate the alliance both for the family and for the therapist. The first part is designed to gather information on behavioral indicators for each participant. In the second part, the rater is asked to make an overall assessment for each of the dimensions of the instrument, awarding a score that can range from −3 (problematic alliance) to +3 (strong alliance). The instrument assesses the frequency of behaviors and the intensity and tendency of each dimension (Friedlander et al., 2005). The tool has been shown to have an acceptable degree of reliability. The first test of the Spanish version yielded correlations between 0.78 and 0.93, while for later studies the values were between 0.75 and 0.95 (Escudero et al., 2008; Friedlander et al., 2008).

A semi-structured interview was used to assess therapeutic change in the patient based on Campo and D'Ascenzo's (2010) individual and family intervention model in systemic relational psychotherapy (D'Ascenzo, 2021). The questions explore five different thematic areas: perception of the problem, self-definition, interpersonal relations (including aspects of communication), expectations for change, and future perspective.

Procedure

The family gave informed consent for their case to be used for research and teaching purposes according to the regulations of the Family Therapy Centre of the Psychiatry Service of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona. The research did not imply risks and the rights, safety, and well-being of the people involved were respected. The sessions were carried out in a hospital room equipped with a one-way mirror and a video recording system. The observation team and supervisor watched from another room.

The observation team was made up of two psychologists. The degree of reliability between the two observers was calculated using Cohen's kappa coefficient. A randomly selected sample of 30% of the total sessions was analyzed for this purpose. The calculation yielded a mean correlation of 0.99 for the dimension Engagement in the Therapeutic Process, 0.99 for the dimension Emotional Connection to the Therapist, 0.95 for the dimension Safety within the Therapeutic System, and 0.88 for the dimension Shared Sense of Purpose within the Family.

A total of five sessions (the first, second, fourth, sixth, and ninth) at which at least two members of the family were present were analyzed. A longitudinal analysis of the alliance throughout the therapy sessions was carried out in order to gain a more complete picture (Crits-Christoph et al., 2011; Mateu, 2015). The analysis took into account both the initial sessions and sessions later in the therapy process. Following Escudero and Friedlander (2003), a verbatim transcript of the sessions was created in order to ensure that the analysis of the discourse of the therapists and the family would be as precise as possible. The participation of the co-therapist, the supervisor, and the team behind the one-way mirror was analyzed jointly as if there were a single therapist.

Semi-structured interviews with the patient were used to assess therapeutic change. One interview was conducted at the start of the process, and another at the end. The interviews were video recorded and transcribed. Later, a thematic analysis of the transcripts was carried out (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Inter-rater reliability rates of K = 0.91 and K = 0.92 were calculated for themes identified in pre- and post-therapy interviews.

Treatment

The treatment, in this case, was carried out according to the systemic relational psychotherapy model of Campo and D'Ascenzo (2010) for patients diagnosed with BPD developed at the Psychotherapy Unit of the Psychiatry Service of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona, the integrated individual and family treatment (Tratamiento Integrado Individual y Familiar, TIIF).

Campo and D'Ascenzo (2010) and D'Ascenzo (2021) view personality as a phenomenon that undergoes a process of continuous construction based on our interactions with the outside world, especially with others that are significant for us. That is why the focus of their model is not limited to the patient's relationship with the therapist, but instead takes a broader view that encompasses the patient's natural interactions. Additionally, this approach is founded on the conviction that personality disorders are reversible (Benjamin, 1993; Cancrini, 2007, 2012). The epistemological model used here coincides with that of the relational-systemic psychopathology model for BPD (Benjamin, 1993; Cancrini, 2007; Linares, 2012; Selvini, 2008) and borrows from Millon (1998), whose view of personality is based on a comprehensive perspective, one that considers structural and contextual factors in all their complexity and takes into account their evolving nature (Millon & Grossman, 2005).

This model combines individual and family interventions, as well as interventions with different family subsystems, according to the needs that arise in the therapeutic process. Co-therapy is recommended to help manage the emotional burden that tends to characterize these cases. However, the involvement of multiple therapists is not obligatory, especially when the professional in the session has the help of a supervisor or of a team behind a one-way mirror.

The therapies usually last 1–2 years in the most serious cases, with sessions initially held fortnightly and then monthly and vacation breaks (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010). When it is possible to obtain the collaboration of parents who had a good couple adjustment, the duration has been reduced to 10 or 12 sessions (D'Ascenzo et al., 2023).

The therapeutic setting is founded from the beginning on the collaboration of all the significant figures. This helps spark changes in the patient's immediate natural context and makes it more likely that the positive changes achieved in individual sessions will be reflected in the family system as a whole.

The process begins by building the therapeutic context and establishing the therapeutic contract. To do this, a first session is carried out with the entire family, followed by a specific session only with the patient's parents and another only with the patient. Siblings can also be included in family sessions, if there are any (as is the case in this study). If the patient has a stable partner, a session is held with the partner. Subsequently, depending on the therapeutic goals agreed upon with all family members, sessions are carried out with the entire family, with parents, with siblings and only with the patient. The intervention focuses on individual work that requires the patient to take responsibility for the changes necessary to improve the functioning of her personality. At the same time, family sessions are made to improve family relationships to facilitate and consolidate more functional behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. This implies a commitment to change on the part of family members.

The therapy process consisted of 10 biweekly sessions lasting approximately 2 h.

RESULTS

Maybe it's not bad, because now I don't look at her like I did before and think, “What are you going to do next?” You know? We'll see what happens. I try to look at it and say I'm glad we're doing this and let's see what… what steps you can take to be happy with us. I don't know if I'm explaining it well. I don't look at her with suspicion, or I try not to, but with positivity.

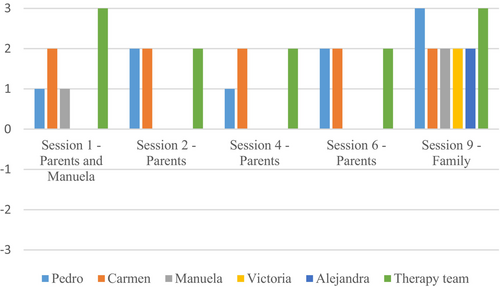

For Sessions 1 and 4, Pedro recorded scores (PT = +1) that indicated a somewhat strong alliance, while in Sessions 2 and 6 he scored higher (PT = +2), and in the final Session (PT = +3) he registered a very strong alliance. In other words, he underwent a positive evolution in this dimension. For Manuela, we also observed an increase in the scores for this dimension between Session 1 and Session 9, as she went from a somewhat strong alliance (PT = +1) to a moderately strong one (PT = +2). For example, when in the first session the therapist asked her what she wanted to work on, she introduced the problem by pointing out: “my relationship and my communication with my parents, so that it doesn't always seems like I'm hiding something.” In the ninth session, she expressed optimism and change saying “Well, it's also feeling… more… involved, that they also count on me, that they want me to be there for them.” These results indicate that the members of the family, especially Pedro and Manuela, increasingly saw the point of therapy, became more involved, and were more likely to believe in the possibility of change. Carmen, too, in the fourth session, expressed optimism and change. For example, she said: “I try not to have the resentment I had toward her.” The therapeutic team, meanwhile, made very strong contributions (PT = +3) during the first and last sessions, and their contribution to the alliance was somewhat strong (PT = +2) in sessions 2, 4, and 6, all aimed at getting the patients involved in the therapy and getting them to work together from the first session to the last. For example, when the therapist asked about the impact of the homework assignment “How did it go last week with the activity you were all supposed to do together? Were you able to meet up in the end?”

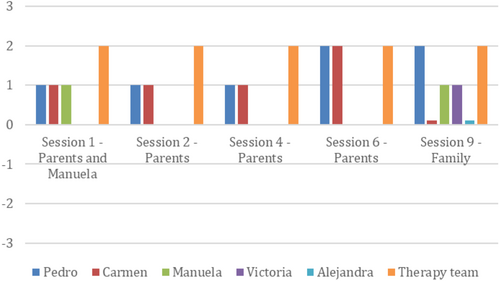

Second, the participants' scores for the dimension Emotional Connection (see Figure 2) were all positive or neutral (PT = +3, +2, +1, and 0) throughout the sessions analyzed. Over the course of the first three sessions (1, 2, and 4) Carmen and Pedro recorded a somewhat strong alliance (PT = +1), but in Session 6 their scores improved, as they registered a moderately strong alliance (PT = +2). However, in the final session, Carmen registered a neutral score (PT = 0), while Pedro maintained a moderately strong alliance (PT = +2). In the case of Manuela, the alliance remained stable, with scores for all the sessions indicating only a somewhat strong alliance (PT = +1). Victoria recorded a somewhat strong alliance (PT = +1), while Alejandra registered a neutral alliance (PT = 0) in the session with the whole family. Thus, the family displayed a certain degree of willingness to commit to a therapeutic process based on trust and affection. This was especially true of Pedro, who on several occasions said during the sessions that he felt understood or accepted by the therapist. For example, in Session 4, Pedro responded this way when the therapist expressed understanding about the lack of communication in Pedro's family of origin and he said: “Of course, you're right. Not much communication, not much affection.” Throughout the sessions, the team of therapist maintained the same score (PT = +2) for the Emotional Connection dimension. Among the most frequently observed indicators of this dimension were the therapists' expressions of empathy. For example, when one of them said to Pedro: “You are in a position in this story, which is a painful story, right? With your family of origin, but it helps you understand Manuela better.”

I see your family and I have a feeling of…, I see mine and this feeling, well as if it were a man walking down the street… but it's my brother, but I don't know. I feel affection for her family when I'm with them, joy, they're all very joyful, but when I'm with my family, they're really closed-minded, dull, sad, don't you think?

My sculpture was of being stronger together. I mean, not having one person here and another there, but all united, and that means a lot of impressive things. It means trusting one another, it means telling one another our problems, and it means asking for help, both my asking them and their asking us. It's being all united, that's what it means, and that's what we're trying to do.

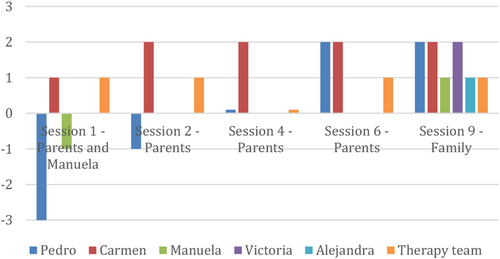

Manuela also underwent an evolution with regard to this dimension, with her scores increasing from that of a somewhat problematic alliance (PT = −1) to that of a somewhat strong alliance (PT = +1). Alejandra registered a somewhat positive alliance (PT = +1), while Victoria recorded a moderately positive one (PT = +2).

The scores for this dimension show that, at the start of the process, Pedro and Manuela in particular did not view therapy as a space where they could take risks or where conflict could safely emerge. We observed that in the first session, for example, Pedro shifted in his chair as many as 16 times, displaying a large degree of non-verbal anxiety, especially when discussing his experiences with his family of origin. Over the course of the process, the participants were increasingly able to view therapy as a safe space. The therapy team's scores indicated a somewhat strong alliance (PT = +1) for all the sessions with the exception of Session 4, when their score was neutral (PT = 0). For example, in the first session, the team asked the parents to name three positive aspects of Manuela, but they mentioned a negative aspect, and the team protected Manuela by saying: “But let's not move on to the negative. It was three positive things.” Another example is in the sixth session when the mother said that she didn't see her daughter as capable of changing, and the therapist protected her by saying: “We are helping her, but it is important that you see her as capable.”

Go ahead, go and tell your story with your words, because that's what this is all about. You don't have anything with us because everything she says is a lie, so what kind of relationship can we have if she lies and creates a world that, would say, has nothing to do with reality.

It sounds like a beautiful story, of love, of parents who take an important step, right? At a time when they already have two daughters and they have another child, and it was difficult, so it wasn't something you took lightly like, “OK, let's have another child,” right.

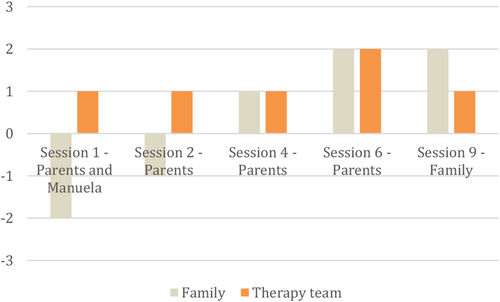

It is worth highlighting that in the ninth session, the therapists referred 15 times to the family's shared values, experiences, needs, and feelings.

With regard to the second objective of this study, five categories were identified to describe therapeutic change: definition of the problem, self-image, interpersonal relations, expectations of change, and future perspective.

In the initial session, the first category, Definition of the Problem, was split into two subcategories, one dealing with the patient's definition of the problem with regard to herself and the other covering the relational part of the problem. The patient clearly saw herself as having problems because she gave others the impression that she did not care about anything, that she had no empathy and never offered apologies or thanks. She justified this by saying that she did not express her feelings perhaps because she did not know how to. She said:

Because my problem is that it seems like I don't care about anything. But it's just that I don't show it. Because maybe I don't know how. I've been keeping everything to myself all my life. Then, you start to lie more and more. It's a snowball effect, so it gets bigger and bigger.

In the relational part of the definition of the problem, the patient said that her parents may have been too overbearing and that she had a hard time relating to them. She always saw her older sisters as role models, although she sometimes felt unfavorably compared to them. She said: “They're your sisters, they're the model you have at home, and unconsciously you end up thinking that you want to do what they do.” Once the treatment was over, Manuela described the change in her attitude toward her parents as having led her to feel more comfortable about sharing things with them and to have more open lines of communication. She expressed: “Now, I want to spend the afternoon with them. I'm calmer because I know we're going to get along well, and I don't try to run away or hide.” In terms of the relationship, the change is reflected when she said: “It makes me feel good because it means that everyone wants me to get better. That's why we're coming here and doing these things… I try to look at the positive side.”

With regard to the patient's Self-Image, at the time of the first interview, Manuela said she was introverted and had low self-esteem. She remembered having been more affectionate when she was younger, but not with her parents. After her treatment, her self-image had changed in that she saw that she played a central role in the family in a positive sense. She said: “Right now, I'm at the center of things to make sure things get better and I'm well.”

Two subcategories were found with respect to Interpersonal Relations, one consisting of relations within the family and the other dealing with relations outside the family. Within the Family, the patient detailed the difficulties she had in her relations with her parents because she thought they were too overbearing. For this reason, she said that she maintained a cold, distant relationship with her parents to prevent them from asking too many questions. Outside the Family, she reported that she had always had two groups of friends and that she had maintained these friendships and her relationship with her partner, whose support she said she could count on. At the end of the treatment, the patient's view of the family was more based on unity and trust. She expressed: “All together, more trust and communication, fewer worries.”

There were also two subcategories within the category Expectations for Change, one referring to individual changes and the other referring to relationships. In individual terms, she said she thought that change was impossible, while in the relational subcategory, she expressed skepticism about her parents' ability to change the way they treated her, even though she thought a change was needed. At the end of the process, the patient, on an individual level, highlighted the importance of her contributions to therapy. She said she felt she had been able to communicate better with her family members and that she knew she could count on them and ask for help if she had problems. She said this made her feel less burdened and calmer in her everyday life. In terms of relationships, the change took the form of expressions of hope. “I think things are going to continue in this way, gradually getting better, that my relationship with all of them will be better for when we meet up and for everything.”

In the category Future Perspective, before the treatment, the patient expressed a desire for the relationship with her parents to improve, for them to be able to communicate with her as they would with anyone else and not be so concerned about her. Upon finishing the treatment, in this category, the patient said that she was very pleased with the work they had done together and that she hoped things would continue to advance in the same direction. She also said she wanted to involve her partner more and improve her expectations at work by looking for a more qualified and rewarding job.

DISCUSSION

The objectives of this study were to describe how the family alliance facilitates therapeutic change and to analyze how this alliance affects the individual and relational functioning of a patient with BPD. These objectives have been met through the case study presented here. The case was characterized by a dynamic, positive evolution of the construction of the therapeutic alliance throughout the therapeutic process. The results are evidence that both the family and the team of therapists collaborated actively to building the alliance and that the contribution of these parties is essential to the formation of a successful alliance (Bordin, 1979). Additionally, the individual therapeutic changes that occurred in the patient between the first and final session were clinically significant, indicating an improvement in the patient's symptoms and her relationships with her family.

Following the TIIF model (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010; D'Ascenzo, 2021), we have been able to confirm the potential of working with the family in the treatment of a person with BPD. In this case, much of the work was done with the patient's parents. The main focus was on strengthening parental relationships in order to promote functional responses in the family as a whole. This method is especially appropriate in patients with BPD, as Campo and D'Ascenzo (2010) have observed that these patients' parents tend to display certain negative biases in their approaches to their children. This was the case of Pedro and Carmen during the initial sessions. Therefore, the goal is to help them adopt a more positive perspective. This was reflected in the final session, when all the members of the family were able to see the progress and changes that had been achieved by Manuela and by the rest of the family. The favorable relational context that was built with the parents made it possible for them to respond effectively to their daughter's affective needs and to help her modify her self-image.

The family started therapy with a feeling of hopelessness and with a great deal of hostility among its members. It was essential to negotiate the objectives and to get everyone involved, and it was critical to forge a strong emotional link between the family and the therapist, as well as to establish a safe setting and a feeling of unity among the members of the family (Friedlander et al., 2018). Additionally, as Blow et al. (2007) and Horvath and Bedi (2002) have pointed out, the alliance is constructed jointly by the therapist and the patient, meaning that the participation of both systems is critical. The therapy team was consistent in terms of its contributions and recorded positive or neutral scores for all the dimensions, thus contributing to the establishment of the therapeutic alliance.

In general, the scores for all the dimensions registered by the members of the family tended to increase as the process advanced, although in some cases they remained steady. It seems that at the start of the process the dimensions of Engagement in the Process, Emotional Connection, and Safety played an important role. As the process went on, however, the dimension Shared Sense of Purpose took on greater relevance. This dimension tends to vary the most over time (Escudero et al., 2008). In fact, despite the low scores for the early sessions, the overall analysis of the family therapeutic alliance in this case shows a favorable evolution of the dimension Shared Purpose when the process as a whole is assessed. An earlier study by D'Ascenzo et al. (2019), which analyzed only the initial stage of therapy, recorded low scores for this dimension. In fact, when therapeutic alliance was analyzed throughout the process in the following study, Safety and Shared Purpose were more relevant in the evolution of the therapy than in the initial stage, and improved thanks to the contributions of therapeutic interventions and the use of sessions with the family subsystems (D'Ascenzo et al., 2023).

It is worth noting that in the first session, the family recorded low scores for all the dimensions. The poor intra-system alliance and the lack of unity among the members of the family were evidence of the fragmented relationships between the parents, Pedro and Carmen, and their daughter, Manuela (Pinsof & Catherall, 1986). In light of these initial difficulties, the therapy team strove to create a vision of unity and to establish alliances with each member of the family in an effort to avoid phenomena such as the “divided alliance” (Muñiz de la Peña et al., 2009).

Friedlander et al. (2006) specify that the dimensions of SOFTA are interconnected and complementary. Nonetheless, it is necessary to carry out a detailed analysis of each individual dimension. First, we observe that the dimension Engagement in the Therapeutic Process played a central role in the initial sessions. As the process continued, the family members became more involved in defining their goals, introducing problems and identifying the positive changes that were occurring. It is worth highlighting the contributions of the therapeutic team in this dimension. In fact, it is here that they recorded their highest scores, registering the maximum possible score in the first and the ninth session. As Escudero et al. (2008) have written, contributions to the dimension Engagement are essential in the first session. This study underlines the importance of the therapy team's contributions to the dimension Engagement from the start and continuing throughout the process, thereby confirming that it is desirable for the therapist and the team to play an active role in this dimension (D'Ascenzo et al., 2019, 2023).

The parents also underwent an evolution with regard to the dimension measuring Emotional Connection to the Therapist, while Manuela's scores for this category remained constant. The family clearly saw that their relationship with the therapeutic team was based on trust, affection, and interest. On many occasions, family members showed that they felt understood by the therapists. This observation is worth underlining because, as Linehan (2003) pointed out, patients with BPD tend to have difficulties in their interpersonal relationship and suffer from a lack of validation from family members. In this case, though, the strong interventions by the therapists from the first session onward helped them to forge a solid bond with the family. This allowed them to avoid ruptures in the alliance that would have made it difficult for the therapeutic process to achieve a positive outcome (Anderson et al., 2016; Gersh et al., 2017). Unlike in the previous studies that showed improvement during the therapy for Emotional Connection (D'Ascenzo et al., 2019, 2023), here there was no evolution on the part of Manuela in this dimension, but the patient did record positive scores for Emotional Connection from the beginning of the process. In this context, it is worth adding that Manuela was suffering from a comorbid episode of major depression in addition to BPD. Her depressive symptomology and the accompanying decrease in volatility might explain her lack of evolution (but consistently positive scores, as her involvement in the process was satisfactory from the start) when it came to Emotional Connection.

The dimensions Safety within the Therapeutic System and Shared Sense of Purpose within the Family saw the greatest variation in scores over the course of the process. In the first session, both Pedro and Manuela registered negative scores for Safety. Pedro's score was particularly low, indicating a highly problematic alliance. This session was marked by anxiety on the part of the family members as well as a number of nonverbal protective or defensive gestures. As Escudero et al. (2008) and Montesano (2015) have pointed out, in these sessions the emergence of conflicts and tension is only to be expected, and the therapist must be prepared to deal with these complexities. However, as the process goes on, the scores for this indicator increase significantly, showing that patients increasingly view therapy as a space where it is safe to take risks. In other words, it is a setting where they can feel comfortable and where conflict can be managed such that the participants do not hurt one another. Pedro's score for Safety increased significantly in Session 4, when he was able to open up a number of times as he shared his anxiety while he detailed his limited relationship with his family of origin and discussed his childhood and adolescence with his parents and siblings. In this session, Pedro was able to make a strong emotional connection with his daughter via these memories of his relationship with his family of origin.

Finally, there was also an evolution in the dimension Shared Sense of Purpose, which refers to the alliance within the family. This indicator was negative in the first session, which was characterized by hostile comments, statements of blame, and avoidance of eye contact. The scores were positive, though, in later sessions, when the family members joked, validated one another, expressed agreement, and mirrored each other's posture. These results echo those of the previous studies by D'Ascenzo et al. (2019, 2023). As Lambert et al. (2012) have observed, in family therapy the alliance among the family members themselves plays a decisive role. Our study provides further confirmation of the importance of working with the family (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010; Cancrini & De Gregorio, 2018; D'Ascenzo, 2021; Linehan, 2003) to facilitate therapeutic change, work that may have borne fruit in the final session, when instead of hostility from the parents, there were jokes and positive comments. It is also worth highlighting the increase in the score for this indicator in the sixth session when the parents discussed their history as a couple. This session was marked by words of agreement and jokes, indicating a functional marital relationship (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010). The therapeutic team, meanwhile, consistently made somewhat strong or moderately strong contributions to the alliance, especially when it came to identifying feelings and experiences that the parents shared (Friedlander et al., 2018).

Again, the dimensions that underwent the greatest evolution over the course of the process were Safety and Shared Sense of Purpose. These findings coincide with those of earlier studies of the therapeutic alliance in couple therapy by Artigas et al. (2017), Friedlander et al. (2006), and Mateu et al. (2014). The results do contrast, however, with the family therapy studies by D'Ascenzo et al. (2019) and the meta-analysis by Friedlander et al. (2018), where the greatest changes were found in Safety and Emotional Connection to the Therapist. This difference might be attributable to the fact that, in this case, most of the sessions analyzed were with the parents rather than with the whole family. In other words, there might be a certain connection between Safety and Shared Sense of Purpose and the specific therapeutic context of the couple.

There is a great deal of consensus in the research on the need to create a safe setting where the members of the family can take risks and face topics that might lead to conflict. As D'Ascenzo et al. (2019) theorized, the dimension Shared Sense of Purpose might be negatively affected by the presence of the impulsive and aggressive symptoms of the patient during family sessions, and working with the parental subsystem might help to facilitate this aspect of the alliance and, in doing so, benefit the therapeutic process as a whole.

Following the TIIF (Campo & D'Ascenzo, 2010; D'Ascenzo, 2021), it was possible to help the patient become aware of how her behavior could shape others' responses. By encouraging her to adopt a proactive attitude with the aim of achieving her goals, the therapists were able to promote positive interactions within the family, which, in turn, had positive effects on the patient's self-image. Thanks to the construction of a favorable relational context characterized by trust, safety, and emotional stability, it was possible to fuel the belief that change was possible and to successfully find a way to meet the patient's legitimate emotional needs. The most substantial findings with regard to therapeutic change between the narrations collected in the first and the last individual sessions with the patient were connected to her view of her central role in the family. At the start of the process, she saw herself as representing a problem to be dealt with, while at the end she perceived herself more as the focus of her family's interest and affection. There is also evidence that, as the family used therapy to become closer, build trust, and show that they valued Manuela's abilities, she was able to construct a more hopeful vision of the future. This optimism was based on improved self-esteem and aspirations to do better in her work and studies and in her relationship with her partner. The changes in the overall family context were reflected in positive changes in Manuela's individual and relational functioning. Meanwhile, thanks to the family's greater understanding of some of the problematic aspects of her personality and how they were connected to her individual development and her family relations, Manuela was also more prepared to take responsibility for modifying her ways of expressing herself and relating to others. She was able to formulate a plan for her future that was appropriate for her stage in life as a young adult (D'Ascenzo, 2020).

Because this is a single-case study, the results cannot be generalized to other cases. As such, in future research, it would be desirable to expand the analysis to a greater number of cases in order to forge closer links between research and professional practice in this area.

In conclusion, this case study has allowed us to collect significant information to contribute to the knowledge about how the therapeutic alliance is established in systemic relational psychotherapy for families with a member who has been diagnosed with BPD and how this affects therapeutic change. The results coincide with those of earlier studies (D'Ascenzo et al., 2019, 2023) and might help inform the decisions of other therapists with similar cases as to the types of interventions to be used.

The study shows that a therapy model that combines individual and family sessions as in the TIIF can facilitate the construction and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance in BPD and contribute to therapeutic change. Working with subsystems seems to be useful both in favor of the therapeutic alliance and in promoting changes. Interventions aimed at building the family therapeutic alliance and at modifying family's communication and relationship patterns can lead to synergy in that it can affect both the relational context and individual functioning, thus facilitating therapeutic change. This is consistent with the principles of the systemic-relational model. Additionally, the results support the usefulness of family therapy for BPD. When it is possible to enlist the collaboration of parents and siblings, there is a chance to mobilize a more positive and less problematic vision of the person with BPD through a change in self-image and a greater expectation for change and future perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the Escuela de Terapia Familiar Sant Pau of Barcelona, the therapeutic team, and the families for allowing the therapy that is the subject of our research and we acknowledge Valentín Escudero for being a reference.