A socioemotional network perspective on momentary experiences of family conflict in young adults

Abstract

Family conflict is an established predictor of psychopathology in youth. Traditional approaches focus on between-family differences in conflict. Daily fluctuations in conflict within families might also impact psychopathology, but more research is needed to understand how and why. Using 21 days of daily diary data and 6-times a day experience-sampling data (N = 77 participants; mean age = 21.18, SD = 1.75; 63 women, 14 men), we captured day-to-day and within-day fluctuations in family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness. Using multilevel models, we find that days of higher-than-usual anger are also days of higher-than-usual family conflict. Examining associations between family conflict and emotions within days, we find that moments of higher-than-usual anger predict higher-than-usual family conflict later in the day. We observe substantial between-family differences in these patterns with implications for psychopathology; youth showing the substantial interplay between family conflict and emotions across time had a more perseverative family conflict and greater trait anxiety. Overall, findings indicate the importance of increases in youth anger for experiences of family conflict during young adulthood and demonstrate how intensive repeated measures coupled with network analytic approaches can capture long-theorized notions of reciprocal processes in daily family life.

INTRODUCTION

Family conflict refers to expressions of resentment, hostility, tension, and criticism in the family (Fosco et al., 2012) and is related to internalizing problems in youth, including anxiety and depression (Moos & Moos, 1994). Family systems theory provides a set of theoretical principles to guide the conceptualization of patterns of family interactions, including conflict (Minuchin, 1985). The family, from this perspective, is a site of everyday exchanges among family members and between family members and settings external to the family, including parents' places of work, young adults' work and college settings, and other community institutions (Larson & Almeida, 1999). In these exchanges, family members are affected by and affect others. For example, parent-youth conflict may be both a consequence of past parent anger and an antecedent of future parent anger (LoBraico et al., 2020) and daily interparental conflict may spill over to parent–child conflict later (Mastrotheodoros et al., 2022). Quantifying these exchanges is important because certain configurations of these exchanges may place family members at risk for poor mental health outcomes (Larson & Almeida, 1999). Coming from this family systems perspective, this paper develops a socioemotional network perspective on momentary experiences of family conflict in young adults.

A family systems and network perspective on conflict and emotions

One potentially fruitful way to quantify the importance of family conflict for youth psychopathology is to focus on the interplay between the emotional lives of family members and everyday family conflict experiences (Larson & Almeida, 1999). Emotions can be functional, alerting us to important changes in our environments and facilitating our responses to those changes (Izard, 2009). Yet, emotional intensity and its duration must often be modulated to enable optimal engagement in situations (Cole et al., 2004). Emotion regulation is adaptive when emotions exhibit flexibility, persisting until goals are achieved but rising and falling when appropriate to accommodate changing environmental demands (Thompson, 1994). In all families, conflict may arise and negatively valenced emotions may be triggered during interchanges between family members. Here, we define negatively valenced emotions as short-lived affective responses that are experienced as unpleasant, with valence expressed on a continuum from pleasant to unpleasant (Barrett & Russell, 1999). In this study, we specifically focus on three discrete emotions: anger, anxiety, and sadness. In well-functioning families, conflict can be repaired to avoid long-duration conflict and consequences (Leger et al., 2018). In other families, spiraling patterns of interactions where one reaction triggers another's reaction may emerge, leading to instances where both family conflict and negatively valenced emotions are sustained for long periods of time (Minuchin, 1985).

An intensive repeated measures approach

Capturing the exchanges between conflict and emotions remains challenging but is being facilitated by recent efforts to quantify family functioning on relatively short timescales (e.g., day-to-day; Fosco & Lydon-Staley, 2020; Leonard et al., 2022). Examining fluctuations on timescales shorter than monthly or yearly changes reflects that all types of families have “bad days” and “good days” on which they are more or less conflictual than usual (Chung et al., 2009; Cummings et al., 2003). These fluctuations in family conflict have implications for emotional experiences, with days of higher-than-usual family conflict, for example, being days of higher-than-usual negatively valenced emotions.

In addition to providing insights into how short timescale (e.g., daily) fluctuations in family conflict are associated with fluctuations in emotions, intensive repeated measures data facilitate the construction of feedback loops like those posited by family systems theory (Brinberg & Lydon-Staley, 2023). This ability to capture complex feedback loops and spirals with intensive repeated measures is perhaps best seen in an emerging emotion network perspective (Lydon-Staley et al., 2019; Pe et al., 2015). An emotion network perspective contextualizes the experiences of a discrete emotion within a broader emotion system comprising multiple discrete emotions and their associations with one another across time. Emotion networks capture the intuitive notion that one's current emotional state may give rise to other emotions. For example, one may feel embarrassment over an angry outburst—a form of secondary emotional response that has long been emphasized in emotion theory (Gross & Muñoz, 1995) and observed in empirical studies that capture the moment-to-moment transfer of emotions across time and states (Pe & Kuppens, 2012). Some degree of emotion transfer across time and states is normative. Emotion networks that support the spread of negatively valenced emotions across time and states, however, may place people at risk for psychopathology. Indeed, individuals with negatively valenced emotion networks that facilitate the substantial spread of emotions across time and states tend to exhibit a high number of depressive symptoms (Shin et al., 2022).

This emotion network perspective posits that emotions persist across time in strongly connected networks, as activity in one emotion is transferred to another emotion via causal associations. This spreading of emotional activity through networks is analogous to the behavior of two sets of domino tiles: one in which the tiles are far apart and a second in which the tiles are close together. In a densely connected emotion network, the set of domino tiles are close together, and when one tile falls it causes other tiles to topple, rippling through the system (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). In a more sparsely connected emotion network, the set of domino tiles are far apart and when one tile falls the other tiles remain standing.

Embedding family conflict experiences in emotion networks

Emotion networks have been expanded to include not only discrete emotions but also social experiences that act as both causes and consequences of emotions (Yang, Ram, Gest, et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). Social experiences that occur in the family context, in particular fluctuations in conflict, make natural additions to a socioemotional network. We may posit, in line with family systems theory and recent empirical findings (e.g., LoBraico et al., 2020), that family conflict and discrete emotions are both causes and consequences, that impact one another across time.

Both family systems theory and an emotion network perspective share notions of the importance of a return to homeostasis following perturbation (Minuchin, 1985; Yang, Ram, Gest, et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). Experiences of family conflict and negatively valenced emotions are normative. Instead, sustained and repeated experiences of family conflict and negatively valenced emotions can place individuals at risk for psychopathology. By embedding variables that capture family conflict within socioemotional networks, we can use appropriate tools to capture the extent to which, after an increase in family conflict, the conflict perseverates over time as it impacts, and is impacted by, negatively valenced emotions.

In particular, impulse response analysis is a tool that may capture the complex spread of conflict activity through a socioemotional network (Lütkepohl, 2005). Once a temporal network that encodes the predictive associations between emotions and family conflict experiences across time has been constructed, an impulse response analysis simulates an exogenous impulse to certain socioemotional network nodes, one node at a time. After the system receives the perturbation, the propagation of this impulse through the network and the time-lagged symptom network edges can be charted. The impulse response function shows the hypothetical change in conflict or discrete emotion in response to a stimulated increase in conflict or emotion intensity over several time points, capturing the continuous interplay between nodes in a network and matching theoretical notions of feedback loops.

Family conflict in young adulthood

Changes in family experiences occur as youth transition from adolescence into young adulthood, become more independent from their families, move into new homes, finish school, and begin careers (Arnett, 2000). Yet, conflict remains an important dimension of family life during this time of instability and shifting of family relationships (Johnson et al., 2010). Indeed, family conflict sometimes decreases throughout adolescence and into young adulthood (Whiteman et al., 2011) and the family environment is theorized to lose its dominant function when environments outside of the family become more important (Arnett, 2000). Even in the context of these changes, however, family conflict remains associated with young adults' psychopathology (Lopez, 1991). Young adults who perceive their families to be cohesive feel less stress when transitioning to college compared to those who perceive their families to be less cohesive (Johnson et al., 2008). Similarly, those who report more frequent and intense conflict tend to experience more stress than young adults who report less family conflict (Lopez, 1991).

Zooming into the everyday lives of young adults will provide a complementary perspective to this long-timescale work and, by taking a socioemotional network perspective, nuanced insights into everyday exchanges between family conflict and young adult emotional experiences will be achieved. With the greater independence young adults have from their families relative to adolescence, both in terms of less time spent with families than with friends and romantic partners (Fuligni & Masten, 2010) and in terms of many leaving home for the first time to attend college or work (Arnett, 2000), a plausible hypothesis is that young adults may exert stronger spillover effects on family conflict than during adolescence. Indeed, although young adults take advantage of their individuality and independence from their families (Tsai et al., 2013), they may remain active in seeking parental support and guidance as they face the challenges associated with becoming an adult and, as a result, become drivers of family conflict as they bring their experiences with stressors into the family environment.

The present study

Guided by family systems theory, we evaluated the interplay between family conflict and three negatively valenced emotions (anger, anxiety, and sadness) at two timescales in a community sample of young adults, approximately 48% of whom were full-time college students. With daily reports, we draw from previous studies on adolescents showing that an increase in family conflict represents a stressor that is associated with increased negatively valenced emotions (Fosco & Lydon-Staley, 2020) and extend that work to young adults. Given the continued importance of the family in adulthood, despite some changes (Johnson et al., 2010), we hypothesize that days of higher-than-usual family conflict will be days of higher-than-usual negatively valenced emotions (H1).

To better understand the associations observed at the daily timescale, we next use intra-day measurements of family conflict and negatively valenced emotions to construct socioemotional networks that articulate the interplay between family conflict and negatively valenced emotions. We hypothesize that family conflict will show interplay with negatively valenced emotions across time, such that changes in family conflict at one time point will be associated with changes in emotions at the next time point and vice versa. Given the increased independence, young adults have from their families relative to adolescents, along with their continued tendencies to turn to the family for support when experiencing difficulties, we hypothesize that the influence of young adult negatively valenced emotions on family conflict will be more pronounced than the influence of family conflict on young adults' emotions (H2).

To further understand heterogeneity in socioemotional networks and their associations with psychopathology, we construct person-specific socioemotional networks and use impulse response analysis to quantify between-person differences in how increases in family conflict perseverate over time. The perseveration of family conflict is indicative of difficulty returning to homeostasis following perturbation, resulting in sustained and repeated experiences of family conflict theorized to place people at risk for psychopathology (Minuchin, 1985). As such, we hypothesize that socioemotional networks that facilitate the perseveration of family conflict will be associated with greater experiences of anxiety and depression (H3). By testing these hypotheses, our study offers a fundamental contribution to quantifying and understanding the reciprocal dynamic between young adults' family conflict and negatively valenced emotions.

METHOD

This investigation used data from the Networks of Daily Experiences (NODE) study. The variables used in the presented study have not been reported on previously (but see McGowan et al., 2022, for greater detail about the protocol). All research was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Pennsylvania. All data and code used in the present study is available at this Open Science Framework page: https://osf.io/8jhuk/?view_only=32c209abc9164e698da7c6479e6d4e52.

Participants

Participants were 77 young adults (M = 21.18 years, SD = 1.75, 63 women, 14 men; see Table S1 for additional participant demographic characteristics) recruited from Philadelphia through poster, Facebook, Craigslist, and university research site advertisements. Individuals were eligible if they met 5 criteria: (1) were between 18 and 25 years of age; (2) had consistent access to a home computer/laptop with internet; (3) owned a smartphone; (4) were willing to complete a 2-h laboratory visit; (5) were willing to install a free app on their smartphone and computer. Most participants (87%) reported their mother as their first caregiver and most participants lived full time (23%) or some of the time (55.4%) in the same household with people identified as their first caregiver. Table S2 presents the family structures of all participants.

Procedure

Participants attended a laboratory visit and then completed 21 days of daily diaries and experience-sampling. Links to the end-of-day daily diary surveys were sent via email at 6:30 pm. The experience-sampling protocol consisted of a morning survey and five further surveys delivered via LifeData. The morning survey was sent at 7 AM (n = 1), 8 AM (n = 51), 9 AM (n = 13), 10 AM (n = 10), and 11:10 AM (n = 3), with participant-specific times elicited at the laboratory session to maximize completion of the morning survey. The morning survey came at the same time each day. The other five momentary surveys were distributed randomly throughout the day, with at least 30 minutes between each prompt. Participants were compensated with a payment card (see Supporting Information for payment details). Data collection began in July 2019 and ended in March 2020 when laboratory visits were no longer possible due to COVID-19.

Measures

The present study used participants' reports of demographic characteristics, family conflict, anxiety, and depression from the laboratory visit, as well as daily and momentary reports of family conflict, family interactions, sadness, anger, and anxiety.

Dispositional family conflict

Dispositional family conflict was measured using the conflict subscale of the family environment scale (Moos & Moos, 1994). The conflict subscale describes the amount of openly expressed conflict among family members with items such as “Family members fought”. Answers were measured on a 5-item Likert scale (1 = “Almost Never” and 5 = “Almost Always”). The measure showed high internal consistency (Cronbach's = 0.84).

Daily and momentary family conflict

The daily measure of family conflict, used in previous daily diary studies (Fosco & Lydon-Staley, 2020), contained two questions: “Family members criticized each other” and “Family members fought”. Both questions were measured using a slider ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Very”) with increments of 1. Daily family conflict exhibited an intraclass correlation of 0.43 and a reliable change score of 0.78 (Cranford et al., 2006). The daily measure was adapted to construct a momentary measure of family conflict. Because the measure was asked six times per day for 21 days, the measure was reduced to one question: “Family members are fighting with one another”. Participants responded on a slider from 1 (“Not at all true”) to 100 (“Very true”) with increments of 1.

Daily and momentary anger, anxiety, and sadness

Daily anger, anxiety, and sadness were measured once every day for 21 days using items adapted from the Profile of Mood States—Adolescents (McNair et al., 1981) of the form, “TODAY I felt….?” followed by “angry”, “anxious”, and “sad”. Participants rated how much they felt each emotion on that day, using a slider of 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Very”) in increments of 1. Momentary anger, anxiety, and sadness were measured five times every day using items adapted from the Profile of Mood States—Adolescents (McNair et al., 1981) of the form, “Right now, I feel….?” followed by “anxious”, “angry”, and “sad”, using a slider of 1 (“Not at all”) to 100 (“Very”) in increments of 1.

Daily interaction with family members

Daily interaction with family members was measured as part of the daily diary protocol. The question asked “Which of the following did you interact with (either in person or on the phone/text/social media) TODAY?” and included “Family” as a response option.

Trait anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression were measured subscales from the Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (Chorpita et al., 2000). All questions were measured from a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “Never” and 4 = “Always”). Anxiety ( = 0.78) and depression ( = 0.86) measures showed high internal consistency.

Data preparation and analysis

We first examined how daily fluctuations in family conflict were associated with daily fluctuations in anger, anxiety, and sadness before creating socio-emotional networks that articulated intraday associations between family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness.

Daily fluctuations in family conflict and emotion

We used multilevel models to evaluate the association between daily fluctuations in family conflict and participants' daily anger, anxiety, and sadness. To facilitate a focus on within-person associations among family conflict and emotion (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013), we created two types of family conflict variables: usual family conflict and day's family conflict. The usual family conflict variable was calculated using a grand mean-centered individual mean score across 21 days. An individual with positive values of usual family conflict represents an individual with higher than average family conflict experiences across the 21 days of the study, relative to other people in the sample. The day's family conflict variable was calculated as deviations from the usual family conflict score. Positive values on day's family conflict would indicate a day of higher levels of conflict than usual for that individual. For each of the three emotions (anger, anxiety, sadness), we tested associations between family conflict and the emotion of interest in separate multilevel models.

Socioemotional networks of momentary family conflict and emotion

The daily diary data allowed us to test for concurrent associations between family conflict and emotions throughout the day. We next turned to the experience-sampling data to capture potentially bidirectional, intraday associations between family conflict and emotions. We took a multilevel-vector autoregression (ml-VAR) model approach (Epskamp et al., 2018) to estimate the dynamic associations among family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness where each variable was regressed on the values of all other variables at the previous time point. The mlVAR approach estimated a temporal and contemporaneous network. Edges can be interpreted as how deviations in the intensity of one variable are associated with change in the intensity of another variable (e.g., how increases in family conflict are associated with increases in anger at the next time point). Edges in the contemporaneous network show associations between variables occurring within the same measurement occasion and reflect partial correlations between nodes at the same time while controlling for temporal effects and all other variables within the same measurement occasion.

Person-specific socioemotional networks of momentary family conflict and emotion

We also estimated person-specific dynamic networks of family conflict and emotion. The detrended time series data for the four variables (family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness) were within-person standardized so that each variable for each person had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (Bulteel et al., 2016). We modeled each participants' time series as a 4-node network using a unified structural equation model (uSEM; Gates et al., 2010).

Between-person differences in socioemotional networks, anxiety, and depression

To test the implications of between-person differences in socioemotional networks, we quantified individual differences in how increases in family conflict spread through each participant's network using impulse response analysis (Lütkepohl, 2005). In this approach an impulse is given to the family conflict node and the behavior of the socioemotional network is observed, through simulation, over many time steps. This dynamical process simulates how family conflict's activity moves through the socioemotional network along edges when family conflict becomes transiently increased due to an external perturbation. The temporal profile, showing how family conflict intensity changes over the time steps following the initial impulse, is examined. Specifically, the recovery time of family conflict intensity, defined as the time taken to return to within ±0.01 of equilibrium, is derived via backward search. We searched backward from the end of the time profile to identify the time step k where the intensity of the symptom is first outside the ±0.01 boundary. Recovery time is then quantified as the number of time steps from perturbation to equilibrium. We implemented person-specific uSEM and impulse response analysis using the R package pompom (Yang et al., 2021). To explore the implications of between-person differences in recovery time of family conflict for psychopathology, we calculated the correlation between family conflict recovery time and both trait anxiety and depression. Greater detail on the impulse response analysis, including model equations, is available in the Supporting Information.

RESULTS

We provide descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analyses in Table S3. The number of daily diary days available per participant ranged from 1 to 21 (M = 11.0, SD = 6.06) and the number of experience-sampling prompts available per participant ranged from 5 to 126 (M = 99.24, SD = 31.72). The number of daily diary days completed by participants was not significantly correlated with key study variables. On average, participants reported interacting with family on 72% (SD = 29) of daily diary days.

Daily family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness

Results of the multilevel models examining daily associations between family conflict and emotions are shown in Table S4. Day's family conflict was associated with anger (b = 0.20, p < 0.001, d = 0.24), such that on days when family conflict was higher than usual, anger was higher as well. There were positive but not statistically significant associations between day's family conflict and anxiety (b = 0.11, p = 0.06) and sadness (b = 0.09, p = 0.09). At the between-person level, people from families experiencing higher than the sample average levels of family conflict on average across the 21 days experienced more anger (b = 0.48, p < 0.001, d = 1.08), anxiety (b = 0.43, p = 0.01, d = 0.60), and sadness (b = 0.36, p = 0.003, d = 0.71).

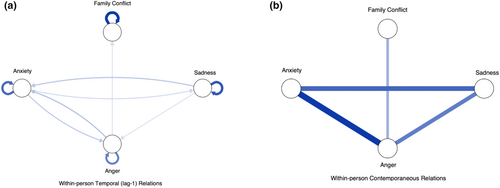

Socioemotional networks of momentary family conflict and emotion: a group model

We next turn to within-day fluctuations in family conflict and emotion. This allowed us to capture potential reciprocal associations between family conflict and emotions. Results from the multilevel vector autoregressive model are presented in Table S5. The edges of the temporal network (Figure 1a) represent the prediction of variables at one measurement occasion by variables at the previous measurement occasion (i.e., earlier in the day) for a prototypical individual in the sample. We find that all associations are positive, indicating that increases in a variable at the current time point are associated with increases in other variables at the next time point. One temporal association emerged between the emotions and family conflict. Previous prompt's anger predicted current moment's family conflict such that increases in youth anger were associated with increased family conflict.

The edges of the contemporaneous network (Figure 1b) represent the co-occurrence of family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness, controlling for both temporal effects and the effects of all other variables at the same measurement occasion. All edges in the contemporaneous network are positive, indicating the reinforcement of associations among variables. When anger is higher than usual, family conflict is also higher than usual. No such association was found between family conflict and anxiety or sadness. The three negatively valenced emotions created a feedback loop such that when an increase in one emotion is experienced, increases in two other emotions are also experienced.

Person-specific momentary socioemotional networks, anxiety, and depression

We next moved from a group model for the prototypical individual in the sample to an estimation of person-specific temporal networks. The estimation of person-specific networks requires more data than the estimation of a group model that pools data across individuals. A person-specific model of the associations among the four variables fit the data of 70 of the 77 (90.91%) individual participants well; the goodness of fit is indicated by at least three of the following four criteria: RMSEA ≤0.08, SRMRs ≤0.08, CFIs ≥0.95, NNFI ≥0.95 (Beltz et al., 2016; Yang, Ram, Gest, et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). Participants for whom good fits were not obtained had less data than participants for whom good fits were obtained, t(76) = −5.77, p < 0.001.

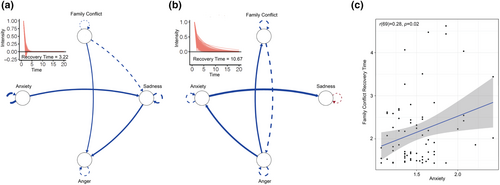

Taking these 70 participants forward, we quantified individual differences in participants' socioemotional networks and their implications for the extent to which family conflict persists across time after perturbation using impulse response analysis (see Figure 2a,b). Specifically, we simulated an increase in family conflict and examined how its intensity persisted across time as an activity associated with family conflict traveled through each person's socioemotional network. We quantified this persistence using recovery time for family conflict and used the common logarithm to reduce the positive skew of the family conflict recovery time variable. Family conflict recovery time was positively correlated with trait anxiety (Figure 2c; r(69) = 0.28, p = 0.02) but exhibited no significant association with depression, r(69) = 0.08, p = 0.49, meaning that more anxious people took longer to recover from family conflict.

DISCUSSION

The present study extends understanding of the role of family conflict in young adults' psychopathology and negatively valenced emotions. We capture daily and momentary fluctuations in family conflict and test their associations with daily and momentary anger, anxiety, and sadness. Consistent with findings that dispositional family conflict is associated with young adults' psychopathology (Johnson et al., 2008; Lopez, 1991), we find that those from families experiencing higher than the average family's level of family conflict across the 21 days of the daily diary protocol reported more anger, anxiety, and sadness. This finding supports the idea that conflict within the family is still a common source of distress among young adults (Arria et al., 2009). We build on this dispositional perspective by capturing within-person associations between family conflict and negatively valenced emotions, finding that days of higher-than-usual family conflict were also days of higher than usual anger, but not sadness or anxiety.

Moving to the intra-day assessments allowed us to construct socioemotional networks that quantified the interplay between family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness across time. Consistent with an emotion network perspective, as well as empirical evidence that emotions may transfer to one another across time and states, a group-level temporal model revealed substantial lagged associations between anger, anxiety, and sadness. Notably, many of these associations were reciprocal, such that increases in anger predicted increases in anxiety, and that increases in anxiety in turn predicted increases in anger.

The observed daily family conflict and anger association is consistent with previous work indicating that daily fluctuations in family conflict are tied to negatively valenced emotions in adolescents (Fosco & Lydon-Staley, 2020) and extends that finding to young adults. A difference that emerged between previous work in adolescents and young adults under consideration in the present study was the specificity of the association between family conflict and anger, highlighting the particular role of anger as an antecedent of family conflict.

Findings offer limited support for circular causality, instead suggesting a unidirectional temporal relation from anger to family conflict. Indeed, the main association involving family conflict that emerged indicated that increases in youth anger predicted increases in family conflict. This relation provides context for the specificity of the association between family conflict and anger at the daily level, indicating that increased anger in young adults may be a driver of increases in family conflict, or that young adults may be more sensitized to perceiving conflict when already angry. That the influence of young adult anger on family conflict was more pronounced than the influence of family conflict on young adult emotions suggests that during this period of life when young adults are spending less time with their families and showing high levels of autonomy relative to adolescence (Arnett, 2000; Fuligni & Masten, 2010), young adults become drivers of family conflict as they bring their experiences with stressors into the family environment. Such an interpretation is consistent with observations that, in the context of increased independence from their families, young adults remain active in seeking parental support and guidance as they face challenges (Fuligni & Masten, 2010; Tsai et al., 2013).

Although no reciprocal association emerged in the temporal network whereby increases in family conflict predicted increases in anger, the contemporaneous network showed that family conflict and anger tend to fluctuate together. When one is higher than usual, the other also tends to be higher than usual. Overall, the construction of socioemotional networks facilitated the capture of long-theorized feedback loops between family conflict and negatively valenced emotions, whereby family conflict may be both a consequence of past anger and an antecedent of future anger (LoBraico et al., 2020; Minuchin, 1985).

We next turned to person-specific socioemotional networks and observed substantial between-person differences in how emotional and family conflict experiences were associated across time. At this person-specific level, reciprocal associations between family conflict and negatively valenced emotions were observed for some participants in the sample (e.g., the reciprocal association between family conflict and anger in the network in Figure 2b). Both family systems theory and an emotion network perspective place importance on these between-person differences, identifying certain configurations of exchanges between emotions and family experiences as more likely to be associated with psychopathology than others (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Larson & Almeida, 1999). Specifically, sustained and repeated experiences of family conflict are theorized to place individuals at risk for psychopathology. Indeed, findings from the impulse response analysis revealed that young adults with socioemotional networks exhibiting patterns of interplay between family conflict and negatively valenced emotions that facilitated the perseveration of family conflict across time after a simulated increase in family conflict exhibited greater trait anxiety.

The current findings emphasize the implications of fluctuations in family conflict and negatively valenced emotions occurring within days and from day-to-day for young adults' anxiety. The finding that youth anger is an antecedent of increases in family conflict reinforces family-systems approaches to intervention, where the everyday exchanges among family members and between family members and settings external to the family (i.e., spillover) are considered as points of intervention (Larson & Almeida, 1999). The finding that sustained family conflict was associated with greater youth anxiety suggests the importance of focusing not simply on the presence of family conflict, but on the extent to which it perseverates across time. This focus on perseveration in family conflict will benefit from emerging ecological momentary assessment approaches in mental health care assessment and treatment settings (McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2018; Piot et al., 2022). An important finding, with implications for practice, is the extent of idiosyncrasy observed across youth when considering the person-specific socioemotional networks. This idiosyncrasy echoes recent work also showing extensive between-family differences in daily parent-adolescent dynamics (Boele et al., 2023) and further suggests the potential utility of ecological momentary assessment approaches embedded within interventions that may facilitate the tailoring of interventions to the specific family under consideration.

Limitations and future outlook

In contrast to survey-based methods that rely on collection over long periods of time (e.g., 30 days; Schwarz, 2007), this study collected intensive repeated measures with daily diary and experience-sampling methodologies, reducing retrospective biases and enhancing ecological validity of the findings (Shiffman et al., 2008). The study sample consists mostly of young college-going women with heteronormative family structure. Determining the extent to which findings generalize to different samples will require more diverse samples. Estimating person-specific models captured heterogeneity in socioemotional networks that had implications for the experience of anxiety but required more data than approaches that aggregated measurements across people. Indeed, person-specific networks could not be constructed for six individuals in the sample due to the length of the time series required for estimation, a difficulty observed in applications beyond family dynamics research (e.g., tobacco withdrawal, Lydon-Staley et al., 2021). Daily and momentary family conflict were measured based on only two items regarding criticizing each other and family members fighting with each other. Although these are two major items that indicate family conflict, other categories such as getting angry and losing temper that are measured in the dispositional family conflict scale were not included. Additionally, although ecological momentary assessment increases accuracy and reduces retrospective bias in self-reports as compared to retrospective reports over longer periods (e.g., past 30 days; Ebner-Priemer & Trull, 2009), people may lack insight into their mental processes (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). This could explain the stronger associations observed in socioemotional networks between anger, as compared to both sadness and anxiety, and family conflict if participants associate conflict with anger more and therefore downplay the concurrent experience of other emotions. Although plausible, this is unlikely to be the only driver of the observed anger-family conflict associations given that associations between anger and family conflict were observed across time (i.e., t − 1 edges in the socioemotional networks) and not just concurrently (i.e., during the same time point in the networks).

In assessing daily interactions with family, we did not specify which family member (e.g., caregiver, sibling) young adults had interacted with that could further disentangle the specific types of family interaction or family conflict that impact young adults. The term family member is also a generic description of members in the family that does not differentiate between members that are family of origin or family of choice. Family of choice members are particularly influential to adults that are in marginalized communities and to their psychopathology (Hull & Ortyl, 2019). Future assessment of family dynamics could fruitfully cover the multifaceted sides of family conflicts as well as more specific definitions of family structure.

The short-term dynamics manifesting on the timescales of hours and days as captured here are embedded in developmental processes occurring over longer timescales of weeks, months, and years (Zemp et al., 2018). Future research will benefit from measurement burst designs wherein bursts of intensive repeated measures protocols that take several weeks to complete are repeated several times over longer periods (e.g., years; Gao & Cummings, 2019; Mastrotheodoros et al., 2022). This will allow tests of how socioemotional networks change during the transition from adolescence into young adulthood and how changes in emotional networks parallel changes in psychopathology.

CONCLUSIONS

Using daily diary and experience-sampling assessments, this study provides evidence of between-person and within-person associations among family conflict, anger, anxiety, and sadness in young adults. Days of higher than usual family conflict were also days of higher than usual youth anger. Examining associations among family conflict and emotions within days, moments of higher than usual anger predicted higher than usual family conflict later in the day. No significant associations emerged in the opposite direction in which youth anger would be predicted by increases in family conflict. This pattern of findings suggests that, on average, increases in youth anger may drive increases in family conflict, or heighten perceptions of family conflict. Substantial between-family heterogeneity in these patterns was observed. Youth with socioemotional networks exhibiting substantial interplay between family conflict and negatively valenced emotions that facilitated the perseveration of family conflict across time exhibited higher than average trait anxiety.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

D.M.L, D.S.B. and E.B.F acknowledge support from the Army Research Office under Grant Number W911NF-18-1-0244. D.M.L. acknowledges support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01 DA047417) and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. D.S.B. acknowledges support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Swartz Foundation, the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the National Science Foundation (IIS-1926757). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.