Online Dialogue

Building the Ecumenical Family with Innovations in Technology

Abstract

In judging the relative merits of online, in-person, and hybrid conferences and meetings, this article takes as a case study the Global Ecumenical Theological Institute (GETI), which took place as an in-person phase held in conjunction with the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches in 2022, following an earlier online phase. The primary objective was to determine the level of satisfaction among participants with the online phase and whether they considered the online phase to have enhanced the productivity of the subsequent in-person phase. The research found that the combination of online and in-person phases was deemed an ideal approach for conferences and programmes such as GETI. While it would have been challenging for young researchers or students without previous assembly experience to keep up with the programme without a preparatory online phase, building friendships and connections solely through the online phase proved to be difficult. Accordingly, it is crucial to recognize the situations where in-person meetings are necessary and effective versus those where online dialogue suffices.

New technologies such as the printing press, radio, telephone, television, and computer networks have enabled rapid communication with larger audiences.1 The internet has become an integral part of our daily lives, organizing both our social and professional tasks. It is increasingly difficult to distinguish between online and offline experiences as they are often intertwined spheres of interaction. Luciano Floridi has referred to this as “a matter of onlife experience,”2 where the boundaries between online and offline environments are blurred, creating safer spaces for self-expression.3

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the global population shifted from traditional offline communication to virtual means of interaction. Individuals worked from home, students attended online lectures, and meetings were held through video conferencing. This change in communication allowed individuals to continue working and have face-to-face interactions from the safety of their homes. The pandemic also impacted religious practices, particularly within Christianity.

While church attendance is a cornerstone of spiritual life for many faith groups,4 most churches and clergy lacked experience in streaming or recording their services. As a result, while some churches began offering online services that included singing, reading, preaching, and communion, others found such practices to be impractical. Overall, COVID-19 highlighted the need for the church to become more flexible.5

The Global Ecumenical Theological Institute (GETI) is an international ecumenical short-term study programme.6 GETI 2022 was composed of two phases: online and in person.7 During the four-week online phase, participants interacted and familiarized themselves with fundamental study materials and the learning environment. The intention was to prepare the participants for the two-week in-person phase, which accompanied the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches (WCC), held from 31 August to 8 September 2022 in Karlsruhe, Germany.8

This article presents the findings of a study on how online dialogue can aid ecumenical conversations. The primary objective of this research was to determine the level of satisfaction among participants with the online phase of the GETI 2022 programme and to discover whether they consider the online phase to have enhanced the productivity of the subsequent in-person phase in Karlsruhe.

This study also explored the extent to which the online dialogue facilitated the establishment of connection among participants. The final segment of the survey inquired about participants’ views on the viability of conducting the entire programme solely in online or in-person format and their willingness to participate in similar online programmes in the future.

What Are the Elements of Effective Online Ecumenical Dialogue?

Effective communication plays a crucial role in promoting ecumenical and interreligious dialogue. There are various definitions of dialogue; within the Christian context, it is also understood as “bilateral and multilateral conversation between formal church representatives concerning church-dividing issues, such as disagreement on doctrine, morals, public prayer, and the celebration of the sacraments, biblical interpretation, structures of ministry and governance.”9 These topics have always been discussed, but what is significant now is that we have “technological advances [that] enable new means of pastoral care that do not require physical proximity.”10 The COVID-19 pandemic has expedited the adoption of modern communication technologies, enabling instant communication with people worldwide and creating numerous opportunities for interfaith or interreligious dialogue. While this mode of communication presents several challenges to interpersonal interaction, it also provides an excellent platform to engage and maintain connections with people.

Digital media, often referred to as “new media,” in comparison with traditional media like radio and television, are changing the dynamics of communication in all aspects of our lives, including how we engage in interfaith dialogue. Although online communication presents certain challenges, it is essential to keep in mind that the basic principles and guidelines for in-person dialogue apply to online communication as well. It is important to maintain the same level of respect and consideration in online interactions as one would in face-to-face conversations, even if the distance created by online communication may sometimes feel impersonal.

Throughout the centuries, Christians who were divided needed to engage in discussions regarding their differences and similarities. Establishment of the World Council of Churches in 1948 as “a fellowship of Churches which accept Jesus Christ our Lord as God and Saviour”11 offered a great dialogue platform, bringing together numerous churches in a conscious effort for unity. The aim of the ecumenical dialogue is “the official engagement in the search for visible unity.”12 This does not imply condescension with the aim of flattering other confessions but is rather an honest recognition of diversity and the joint discovery of a more complete truth. It is insufficient for ecumenical dialogues to be limited to individual participation; instead, the individual should act as a means of promoting and securing acceptance of such dialogues by the wider ecclesiastical body.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Communication

Videoconferencing has replaced in-person meetings and tries to create social presence, providing a good platform for dialogue that is more personal than email or telephone calls. This new way of communicating has impacted every aspect of ecclesial life, including ecumenism, and it has both pros and cons.

One of the main advantages of videoconferences is their cost-effectiveness, as they can save money for organizations by eliminating the need for travel and lodging.13 Additionally, videoconferences can overcome geographical barriers and distances between peripheries and centres. However, a downside is the lack of transition time and spontaneous interaction. Traditional ecumenical meetings typically involve travel, several days of meetings, and opportunities for informal communication.14 Online dialogues begin at a scheduled time, with all participants joining the videoconference simultaneously to begin the agenda. Once the meeting ends, the videoconference is finished, leaving no opportunity for the impromptu bonding that typically occurs during face-to-face meetings. This absence of personal interaction has impacted theological dialogue. In some cases, depending on the subject matter and sensitivity, certain dialogues have been postponed until it was possible to meet in person again.15

The second advantage frequently mentioned is the ease of connectivity from any location worldwide. Thanks to significant advancements in online communication, there are numerous applications available for videoconferencing. Statistics indicate that use of digital tools has led to increased participation in ecumenical initiatives. Online programmes organized by churches have seen higher attendance compared to physical initiatives.16 Livestreamed ecumenical services have also reached more people than could have attended in person. This has led to an improved understanding among different Christian communions.17 However, inequality remains a challenge as some people face issues such as poor internet connectivity in certain countries, difficulty in scheduling meetings across different time zones, and lack of access to digital tools due to cultural or economic reasons.18

The third argument for online communication is its productivity.19 It is generally faster to make decisions during online meetings, and projects can be executed on time. However, there are some limitations to online communication that stem from the lack of physical presence. For example, participants may not be able to observe each other's body language, which can be important for effective communication. In large videoconferences, it can also be difficult to determine when one person has finished speaking and another can begin, which can disrupt the flow of conversation.

The advantages and disadvantages are heavily influenced by the nature of the discourse and the subject matter being discussed. Very sensitive and personal topics may require face-to-face interaction, while certain aspects of dialogue can be carried out effectively via videoconferencing. The next section explores the pros and cons of the online phase of GETI 2022, as indicated by the responses to the Online Ecumenical Dialogue Survey.

Online Ecumenical Dialogue Survey

Introduction and goals of the survey

The online phase of GETI 2022 followed the topics of the WCC assembly. It was divided into six thematic tracks that were prepared individually as well as in the study groups.20 The weekly assignments followed the methodology and could be easily uploaded onto the online platform. During the in-person learning in Karlsruhe, the programme included lectures, spiritual life, participation in some of the assembly programmes, group work, and organized tours.

- To evaluate the degree of satisfaction among students regarding the online phase;

- To determine the number of participants who believe that the online phase contributed to increased productivity during the in-person phase;

- To establish whether students believe that the entire GETI 2022 programme would achieve comparable success if it were conducted exclusively online;

- To ascertain the number of fellow students with whom they still maintain contact;

- To assess participants’ willingness to engage in another ecumenical programme conducted online.

Instruments

This study employed a custom-designed Google questionnaire to gather data from respondents. It included information about their gender, age, continent, study group assignment, and prior experience with online learning. The questionnaire was composed of fifteen questions created by the author, including nine statements with closed-ended responses ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree,” two open-ended questions, and four questions with multiple-choice answers.

Data collection procedure

Due to geographical constraints, data collection for this study was conducted online using Google Forms questionnaires, which were distributed to the participants in the online phase of the GETI 2022 programme. Although official permission from the WCC or GETI 2022 team was not required, I collaborated with the team to obtain a mailing list of all online-phase participants. Prior to distribution, participants were notified about the questionnaire and given the opportunity to opt out if they had any objections or did not wish to participate.

As no objections were raised, a list of email addresses for all participants in the online phase of GETI 2022 was provided to me, along with the instruction to use the bcc option when sending email in order to protect the privacy of participants.21All participants were informed of the fundamental research objectives and were made aware that the data collected would be used solely for research purposes, with the guarantee of anonymity in responding to the questionnaire. Data collection took place in November 2022.22

Characteristics and results of the sample

The study included 35 participants: 22 females and 13 males. The participants represented various regions: 12 from Africa, 10 from Europe, 9 from Asia, 2 from North America, 1 from Central America, and 1 from South America.

The findings revealed that 54.3 percent of the participants were 31 to 40 years old; 45.7 percent were 20 to 30 years old. Additionally, responses were collected from participants across all 10 study groups.

To gauge the students’ opinions of the online phase of the GETI 2022 programme, I sought to determine how many of them had had prior experience with online learning. The results showed that a vast majority, 97.1 percent, had previously engaged in online learning. Only one participant encountered online learning for the first time during the GETI 2022 programme's online phase.

The first set of closed-type scale questions asked the participants about their satisfaction with the online phase of GETI 2022 programme. The majority of participants (25 out of 35, or 71.4 percent) responded that they were either “very satisfied” or “completely satisfied” with the online phase. An even higher number of participants (28 out of 35, or 80 percent) responded positively to the next question, choosing “agree” or “totally agree” that the online phase helped them become more open to ecumenical dialogue during the in-person phase in Karlsruhe. This indicates that the four-week online programme provided an opportunity for participants to interact, discuss, and prepare themselves for the second phase.

Similar results were obtained from the question “Do you think that the online phase increased the productivity of the following phase?” Twenty-five participants agreed or totally agreed that the online phase improved the productivity of the subsequent phase in Karlsruhe. In this context, productivity referred to the participants’ readiness to engage in deep theological discussions at the beginning of the in-person phase due to the good preparation during the online phase.

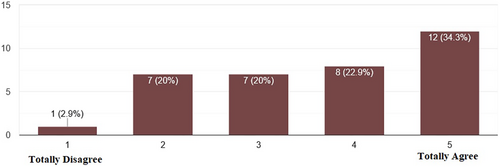

Regarding the possibility of building friendships during the online phase, participants had mixed opinions. Chart 1 displays the responses to the question “Do you think that during the online phase you had already a chance to build friendships?”

The differing responses to the question regarding building friendships during the online phase may be attributed to varying experiences among the study groups. Additionally, it is worth noting that during the online phase, participants were consistently in the same videoconference with facilitators.

As part of the questionnaire, participants were asked whether they thought the GETI 2022 programme would be successful with only an online or only an in-person phase.

The results showed that 48.6 percent, or 17 participants, totally disagreed that the programme would be successful with only an online phase, while only 5.7 percent, or 2 participants, totally agreed. These results were expected.

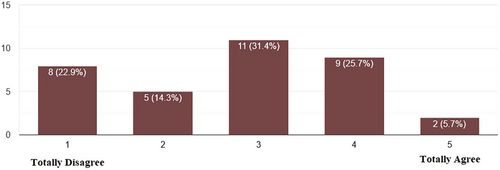

The next question asked whether the participants believed that the GETI 2022 programme would be equally successful with only an in-person phase. Chart 2 shows that only 5.7 percent, or 2 participants, totally agreed with this statement.

Given that our generation has experienced both offline and online conferences, I had anticipated that more participants would believe that a successful GETI 2022 programme could be achieved with only the in-person phase.

As a concluding question, participants were asked whether they believed that the perfect combination for the GETI 2022 programme was a mix of online and in-person phases. A majority (85.7 percent or 30 participants) responded with agreement or total agreement.

In the final section of the questionnaire, the focus was on the connections among the participants after the GETI 2022 programme. The results showed that most participants are still in contact with other participants, with 14.3 percent staying in touch with 10 to 20 people.

Toward the end of the questionnaire, we received positive feedback to the question “How likely are you to participate in online ecumenical dialogues in the future?” A significant number of participants, 77.1 percent (27 individuals) agreed, stating that they are likely to participate in such dialogues.

Conclusion

Previously, face-to-face communication was the only means of communication, but that has changed with the advent of technology. However, human beings remain social creatures who require real-life connections. Online ecumenical dialogue has facilitated communication when alternatives were not feasible. The COVID-19 pandemic expedited this trend, and although it is not satisfactory to everyone, we cannot ignore the valuable role that online communication has played in recent years.

According to Farrell and Turner, face-to-face engagement is still important for complex conversations such as ecumenical dialogue. They argue that churches and ecumenical bodies should acknowledge the significance of transition time and shared physical space in facilitating and sustaining such dialogues.23

This research indicates that GETI 2022 participants have a more favourable view of online dialogue than the authors mentioned earlier. This may be attributable to factors such as age and prior experience with online learning, as each generation has its own preferences. Another factor could be the positive impact of the online phase on the in-person phase. Through four online meetings in August 2022, participants became acquainted with each other, shared their stories and experiences, and provided background details about their churches, allowing for deeper discussions during the physical meetings in Karlsruhe.

The anticipated outcome of the research was that the participants would not consider an exclusively online phase to be sufficient for the success of GETI. The in-person phase was deemed crucial as it allowed for more in-depth discussions, spontaneous interactions, and the development of personal connections. Surprisingly, only two participants believed that this in-person phase was the only key to success. This finding can be viewed from various angles. First, it highlights that programmes like GETI are complex and necessitate thorough preparation to attain favourable results. Second, the large number of participants in GETI require ample time during the online phase to express themselves and establish relationships, which is essential for the dynamics of group and personal interactions during the second, in-person phase.

According to my research, the combination of online and in-person phases is deemed the ideal approach for conferences and programmes like GETI. As a participant in GETI 2022, I can attest to this. WCC assemblies typically involve many participants, delegates, advisors, observers, and overlapping programmes, providing a plethora of information. For young researchers or students without any previous assembly experience, it would be incredibly challenging to keep up with the programme without a preparatory online phase.

We had the opportunity to meet fellow students, make connections, and discuss the topics during the online phase. This was helpful preparation for the in-person phase. However, building friendships solely through the online phase proved to be difficult. This could be due to the group videoconference setup that did not have breakout rooms, as well as the constant presence of the facilitators. Nonetheless, the positive outcome is that participants have kept in touch with each other after the programme, and most are likely to participate again in future online ecumenical dialogues.

It would be beneficial to conduct a comparative analysis of the results of GETI 2022 with those of previous GETI programmes to understand the impact of the pandemic on the outcomes.

The pandemic has familiarized us with the idea of longer online meetings and videoconferences, preparing us for the possibility of conducting productive online dialogues. However, it is crucial to recognize the situations where in-person meetings are necessary and effective versus those where online dialogue suffices. By making this distinction, we can better determine the appropriate medium for ecumenical dialogues in the future.

- 1 This is an edited and revised version of a paper originally submitted as part of the Global Ecumenical Theological Institute (GETI) programme, organized in 2022 under the title “Christ's Love (Re)moves Borders,” in conjunction with the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches. On GETI 2022, see “Global Ecumenical Theological Institute (GETI),” WCC website, https://www.oikoumene.org/what-we-do/ecumenical-theological-education-ete#global-ecumenical-theological-institute. This article has also been published (with minor differences) in Christ's Love (Re)moves Borders: Reflections from GETI 2022, ed. Kuzipa Nalwamba and Benjamin Simon (Geneva: WCC Publications, 2023), 279–88. Reprint permission has been granted by the publisher. All rights reserved.

- 2 Luciano Floridi, The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere Is Reshaping Human Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 79.

- 3 Floridi, The Fourth Revolution, 88.

- 4 John R. Bryson, Lauren Andrews, and Andrew Davies, “COVID-19, Virtual Church Services and a New Temporary Geography of Home,” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111:3 (2020), 360.

- 5 Jerry Pillay, “COVID-19 Shows the Need to Make Church More Flexible,” Transformation 37:4 (2020), 266–75.

- 6 See “Ecumenical Theological Education,” World Council of Churches, 2022, https://www.oikoumene.org/what-we-do/ecumenical-theological-education-ete#global-ecumenical-theological-institute.

- 7 The GETI online phase lasted from 25 July to 20 August 2022. The residential phase took place in Karlsruhe from 28 August to 8 September 2022.

- 8 For more information on the 11th Assembly of the World Council of Churches, see “The Assembly,” World Council of Churches, 2022, https://www.oikoumene.org/about-the-wcc/organizational-structure/assembly.

- 9 Called to Dialogue: Interreligious and Intra-Christian Dialogue in Ecumenical Conversation: A Practical Guide (Geneva: WCC Publications, 2016), 7.

- 10 Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (PCPCU), “Ecumenism in the Time of Pandemic: From Crisis to Opportunity,” A Working Paper: Synthesis of Responses of the Bishops’ Conferences and Eastern Catholic Synods to the 2021 PCPCU Survey on COVID-19 (Vatican City State: Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity, 2022), 20, http://www.christianunity.va/content/unitacristiani/en/documenti/altri-testi/-ecumenism-in-a-time-of-pandemic--from-crisis-to-opportunity----.html.

- 11 T. K. Thomas, “WCC, Basis of,” in Dictionary of the Ecumenical Movement, 2nd ed., ed. Nicholas Lossky et al. (Geneva: WCC Publications, 2002), 1238–39.

- 12 Brian Farrell and Jeanine W. Turner, “Thoughts on Ecumenical Dialogue in the Digital Age,” Ecumenical Review 73:2 (2021), 254.

- 13 “The Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Communication,” ezTalks, 2022, https://eztalks.com/unified-communications/the-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-online-communication.html.

- 14 Farrell and Turner, “Thoughts on Ecumenical Dialogue,” 257.

- 15 PCPCU, “Ecumenism in the Time of Pandemic,” 21.

- 16 PCPCU, “Ecumenism in the Time of Pandemic,” 21.

- 17 PCPCU, “Ecumenism in the Time of Pandemic,” 22.

- 18 PCPCU, “Ecumenism in the Time of Pandemic,” 22–23.

- 19 Mark Lindquist, “Let's Talk: The Pros and Cons of Online and Offline Communication,” 2 October 2019, https://www.ringcentral.com/gb/en/blog/the-pros-and-cons-of-online-and-offline-communication.

- 20 The six tracks were Healing Memories: Remembering and Transforming Past and Present Wounds at the Border (Historic-Theological Track); Kairos for Creation: Transcending Boundaries of Anthropocentrism to Affirm the Whole Community of Life (Eco-theological Track); Witness from the Margins: Connecting with and Holding Space for Those at the Border (Practical-Diaconal Track); Engaging with Plurality: Dialoguing with Communities Across Borders (Intercultural-Interreligious Track); Body Politics: Body, Health, and Healing: Uprooting Systems that Degrade Bodies at the Border (Just Relations Track); and 4th Industrial Revolution and AI: Human Identity in the Context of Global Digitization (special plenary). See GETI 2022, “Thematic and Methodological Focus: An Overview,” World Council of Churches, 28 March 2022, https://www.oikoumene.org/resources/documents/geti-2022-thematic-and-methodological-focus-an-overview.

- 21 When a recipient's address is placed in an email message's bcc (blind carbon copy) line, the message is sent to that recipient but that person's address is not visible to the message's other recipients.

- 22 For the complete results of the questionnaire, see “Online Ecumenical Dialogue,” https://docs.google.com/forms/d/121Y1r4rMxO9zhQsfoT1LWiCyx8gCMzAEWg-dP3weeMk/viewanalytics.

- 23 Farrell and Turner, “Thoughts on Ecumenical Dialogue,” 260.

Biography

Tijana Petković is a research assistant at the Faculty of Protestant Theology, University of Tübingen, Germany.