Antiseizure medication and perceived “fair” cost allocation: A factorial survey among neurologists, persons with epilepsy, their relatives, and a control group

Abstract

Objective

Because resources are limited in modern health care systems, the decision on the allocation of expensive drugs can be supported by a public consent. This study examines how various factors influence subjectively perceived “fair” pricing of antiseizure medication (ASM) among four groups including physicians, persons with epilepsy (PWEs), their relatives, and a control group.

Methods

We conducted a factorial survey. Vignettes featured a fictional PWE receiving a fictional ASM. The characteristics of the fictional PWE, ASM, and epilepsy varied. Participants were asked to assess the subjectively appropriate annual cost of ASM treatment per year for each scenario.

Results

Fifty-seven PWEs (mean age (SD) 37.7 ± 12.3, 45.6% female), 44 relatives (age 48.4 ± 15.7, 51.1% female), 46 neurologists (age 37.1 ± 9.6, 65.2% female), and 47 persons in the control group (age 31.2 ± 11.2, 68.1% female) completed the questionnaire. The amount of money that respondents were willing to spend for ASM treatment was higher than currently needed in Germany and increased with disease severity among all groups. All groups except for PWEs accepted higher costs of a drug with better seizure control. Physicians and the control group, but not PWEs and their relatives, tended to do so also for minor or no side effects. Physicians reduced the costs for unemployed patients and the control group spent less money for older patients.

Significance

ASM effectiveness appears to justify higher costs. However, the control group attributed less money to older PWEs and physicians allocated fewer drug costs to unemployed PWEs.

Key points

- We conducted a factorial survey to examine factors that influence the willingness to accept certain costs for antiseizure medication (ASM) among physicians, persons with epilepsy (PWEs), their relatives, and a control group.

- The amount of money respondents were willing to spend was higher than usually required in current clinical practice.

- ASM efficacy and disease severity justified higher costs while ASM tolerability did not impact the cost allocation of PWEs and their relatives.

- Physicians attributed less money to unemployed PWEs and the control group to older PWEs.

1 INTRODUCTION

With over 70 million people worldwide affected, epilepsy disorders represent a considerable burden for individual persons with epilepsy (PWEs) but also for medical, social, and economic infrastructures.1, 2 Epilepsy-specific costs are high.3 New antiseizure medication (ASM) may improve the course of the disease but may come with higher costs.

With limited financial resources, expensive new drugs may either not be available for many PWEs or may present a heavy burden on health care systems and public resources.4 Modern health care systems have to balance the demand for medical innovations on the one side and limited structural and economic resources on the other side, which makes resource allocation and cost containment increasingly important. Although it is necessary to define criteria on which the decision of who receives a new medical intervention should be based on,5-7 results of a US study suggest a strong public opposition against a governmental cost-effectiveness agency.8 In addition, personal beliefs, the affiliation to a specific group, and public discussions may also affect the treatment decisions for individual PWEs beyond existing guidelines.

Several authors have argued that a widely accepted consensus requires a transparent and open discussion including both health care professionals and the public opinion to make the underlying mechanisms and rationales of resource allocation understandable and acceptable to the society that pays for its health care system.6, 9, 10 To achieve a wide agreement, it seems crucial to explore factors influencing the willingness to pay.

This applies particularly to a chronic neurological disease such as epilepsy, which not only causes direct costs including costs for ASM but also high indirect costs, as the disease contains a significant risk for unemployment and social descent for those affected.11, 12

Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze the preferences of different groups, namely neurologists treating epilepsy, PWEs, and their relatives as well as a control group consisting of public health students and their relatives regarding cost allocation in ASM treatment. We used the design of a factorial study to unmask unbiased drug-, disease-, and patient-related factors that may contribute to the amount of money that was considered justified to spend for ASM.

2 METHODS

2.1 Methodology

Factorial surveys use situation descriptions instead of a sequential polling of isolated items.13 Thus a concrete description of a situation contains several dimensions and the values of each dimension is varied randomly. This allows for the determination of independent effects of each variable on the judgment of the respondent and reduces social-desirability bias.14

The study was approved by the ethics review committee of the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg.

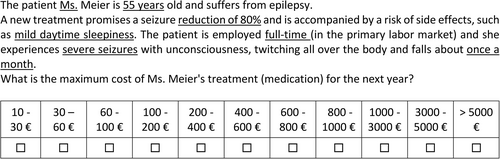

We created vignettes containing a fictional PWE receiving a fictional ASM. The vignette varied in seven dimensions. Each dimension was sparingly provided with values (see Table 1). Sparseness is important to avoid the number of possible combinations becoming too large. In the present study, the universe consisted of a maximum of 2 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 2 × 3 × 2 = 576 different scenarios. A random sample of 100 vignettes was drawn from the universe, and these vignettes were distributed among 10 questionnaire sets. Table 1 details the seven dimensions and the respective values included in the vignettes. To make the scenarios appear realistic, each vignette person was given a neutral-sounding, common German last name (e.g., Meier, Schuster, Schneider). An example of a specific scenario description (= vignette) is provided in Figure 1.

| Vignette factor | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Sex |

|

| Age in years |

|

|

| Employment situation |

|

|

| Disease characteristics | Seizure frequency |

|

| Seizure type | ||

| Drug characteristics | Prospect of success of the medication |

|

| Side effects |

|

- a Technical terms as additional information for physicians only.

- Two drug-related dimensions: Both dimensions were related to the effectiveness of ASM including reduction in seizure frequency and tolerability. We assumed that the better the effectiveness of an ASM, the greater will be the willingness to pay for it, that is, respondents may spend more money for a drug that reduces seizure frequency to a relevant degree without inducing major side effects. In addition, seizure reduction and occurrence of side effects are commonly used parameters in studies evaluating the effectiveness of an ASM.15-17

- Three patient-related dimensions: age, gender, and participation in the labor market. Despite of the principle of equal treatment, it is still of interest to explore whether the acceptance of higher costs is tied to specific patient characteristics.

- Two disease-related dimensions: we chose parameters differentiating between less or more severe forms of the disease, such as seizure frequency and seizure severity (bilateral/generalized tonic–clonic seizures with falls vs absences/unaware seizures with behavioral arrest). Previous studies identified these factors as cost-driving factors in epilepsy treatment.11, 18 We speculated that respondents spend more money for more severely affected patients.

2.2 Questionnaire

Respondents completed two sections, (1) 10 vignettes created as described above, (2) a personal questionnaire. In part 1, respondents were challenged to assess the acceptable maximum costs of ASM per year on a scale of 1 = 10–30 Euros to 11 = >5000 Euros. Part 2 contained questions about age and gender of the respondents.

2.3 Survey administration

Four groups of respondents participated in our study: physicians, PWEs, relatives of PWEs, and a control group with no acquaintances or friends with the condition. The first three groups were recruited through the Epilepsy Center of the University Hospital Erlangen where the questionnaire was handed out to inpatients and outpatients and their relatives. Neurological residents and board-certified neurologists completed the survey at various meetings.

The control group consisted of students of the Master Studies of Public Health of the Technical University Chemnitz, their older siblings, and their parents. Care was taken to ensure that only a maximum of two questionnaires were completed per student (e.g., themselves and one parent) to avoid clustering in similarities of respondents. The master program in Chemnitz is a social science public health program, and biomedical subjects such as drug treatment of diseases are not part of the curriculum. Because the random element was already included in the questionnaires, there was no need to pay attention to random principles in the selection of respondents.19 Therefore, it was sufficient to pay attention to variance of age, gender, and group of persons.

2.4 Response scale

The response scale (see Figure 1) comprised 11 values. Each value represents an interval of potential medication costs. To achieve a better interpretability of coefficients, we processed the response scale in Euros. We included the mean of each category (e.g., value 6 [400–600 Euros] is recoded into 500 Euro). This transformation of the variable leads to a lightly right-skewed distribution (skewness 0.74, kurtosis 2.18).

2.5 Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were done with STATA Version 14. Because the independence assumption of the elements is violated due to the vignette design (one respondent answers 10 vignettes), we conducted cluster-corrected regressions at the respondent level.13 Due to the random procedure when creating the vignettes, corresponding variables are uncorrelated; thus multicollinearity cannot occur.20 As described above, the low skewness indicates an almost symmetrical distribution of the dependent variable. In addition, the kurtosis is just below the normal value of 3, which means that the distribution is somewhat flatter than a normal distribution. Both parameters together indicate a good suitability of the dependent variable for linear regression analysis. Even if the normality assumption does not always have to be given to obtain reliable estimators,21 it is nevertheless pleasing if we can assume a mostly normal distribution. No missing values can occur at the vignette level; therefore, a potential reduction of the power due to missings is excluded. With a power of 80% and a probability of error of 5%, differences of about 320–360 Euros of the annual treatment costs can be detected for each of the four groups of analysis (physicians, PWEs, relatives, and the control group).

3 RESULTS

A total of 194 persons participated in the study: 57 PWEs (mean age (SD) 37.7 ± 12.3, 45.6% female), 44 relatives (age 48.4 ± 15.7, 51.1% female), 46 neurologists (age 37.1 ± 9.6, 65.2% female), and 47 persons in the control group (age 31.2 ± 11.2, 68.1% female). Among the group of physicians, 45 (97.8%) were employed in a hospital and 26 (56.5%) were residents. Residents had a median of 3 years training (range 1–5 years). Of the PWEs, 52 (91.2%) were covered by statutory health insurance (SHI), comparable to the insurance status of German population with 73.27 of 83.24 million inhabitants covered by SHI in 2020.22

3.1 Average costs

On average, physicians allocated the least amount of money for ASM per year (1934 Euros). PWEs gave 2397 Euros, relatives 2532 Euros, and the control group 2326 Euros per vignette-patient.

3.2 Age and employment status of the vignette-person

Across all four respondent groups, there were no differences in accepted treatment costs by gender of the vignette-person (Table 2). The age of the vignette-person did not play a role for PWEs and their relatives. However, the control group significantly reduced the indicated annual treatment costs for 55-year-old PWEs by 360 Euros. Physicians showed the same tendency, and also discounted the costs by 580 Euros when the vignette-person was permanently unemployed (Table 2).

| Physicians | PWE | Relatives | Control group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femalea | −31.21 | 30.51 | −51.77 | 158.27 |

| 55 yearsb | −297.50 | −93.65 | −67.97 | −359.81* |

| Seizure freedomc | 631.05*** | 353.82 | 430.25* | 564.40* |

| Seizure reduction by 80%c | 585.37** | 257.51 | 402.19* | 336.75 |

| Adverse effect: Noned | 376.62 | 163.01 | −67.92 | 579.02* |

| Adverse effect: potentially mild daytime sleepinessd | 233.09 | 65.49 | −92.98 | 345.08 |

| Adverse effect: potentially dizziness with unsteady gaitd | −66.51 | −3.92 | −91.95 | 229.56 |

| Permanently unable to worke | −580.46*** | −181.03 | −69.10 | −255.33 |

| Seizure frequency: 1× per monthf | 591.64** | 537.71** | 366.70 | 644.83*** |

| Seizure frequency: 1× per weekf | 806.09*** | 612.39** | 613.23** | 866.35*** |

| Severe seizuresg | 554.05*** | 594.41*** | 570.17*** | 735.94*** |

| N | 456 | 569 | 439 | 469 |

- Note: The values represent the amount of money respondents would add or deduct for a certain dimension value from the reference value of the dimension. N represents the total number of vignettes per group.

- a Reference category: Male.

- b Ref.: 25 years.

- c Ref.: Seizure reduction by 40%–50%.

- d Ref.: potentially severe allergy.

- e Ref.: employed full time.

- f Ref.: frequency 1× per year.

- g Ref.: mild seizures.

- Stars indicate significance, *p<.05, **p<.01, *** p<.001.

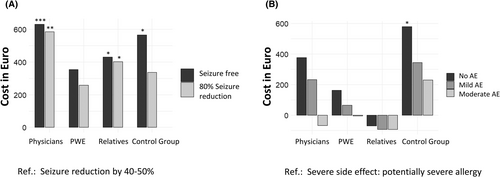

3.3 ASM characteristics

The prospect of efficacy of the ASM was relevant for all respondents (Table 2, Figure 2). For seizure freedom, physicians stated the highest increase compared to the reference category (“40% seizure reduction”) of +631 Euros. Seizure reduction of 80% was significantly rewarded by relatives and physicians.

On the other hand, no or mild adverse effects (“none” or “daytime sleepiness”) were significantly rewarded only by the control group. Adverse effects appeared to have no impact on the cost allocation of relatives.

3.4 Disease characteristics

The price estimate for especially weekly but also monthly seizures was significantly higher than for annual seizures in all respondent groups. Similarly, there was a significant surcharge for severe seizures (tonic–clonic) than for absences (Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, we used factorial surveys to extrapolate the influence of various factors on subjectively perceived “fair” cost allocation in ASM treatment among physicians, PWEs, their relatives, and a control group.

Developed in the 1950s, the factorial survey method has become firmly established in the fields of sociology and psychology and is used increasingly in health research.19, 23-26 Due to the simultaneous presentation of several pieces of information in a hypothetical situation description, the areas of interest can usually be queried more realistically than via conventional survey instruments and the design even more importantly minimizes the risk for answers influenced by social desirability bias.13 By avoiding these socially desirable response patterns, factorial surveys are particularly suitable for complex attitude measurements in sensitive topics19 such as the analysis of the accepted costs of medication in the context of the present study.

In Germany, the annual treatment costs of lamotrigine, the drug of choice in focal epilepsy according the current German guidelines, ranges between 80.25 and 305.54 Euro/patient.27 In Germany, the estimated average annual treatment costs for ASM is about 444 Euros for each patient irrespective of the prescriber or severity of epilepsy28 and 2400 Euros in a tertiary epilepsy center where patients more often have drug-refractory epilepsies.11, 29 In the current study, the average amount of money indicated for a vignette-person with epilepsy ranged between 1933 and 2530 Euros, and thus all groups of respondents were willing to spend more money on ASM treatment, as it is currently required for monotherapy in Germany. Physicians gave the least amount of money and residents tended to assign slightly and nonsignificantly less money than older neurologists (data not shown). Most of the physicians were employed in hospitals and thus were likely not aware of the real ASM costs. Nevertheless, this may reflect the findings of a recent German study showing that physicians feel increasing pressure to consider economic interests of their hospital when making treatment decisions, and their familiarity with cost–benefit assessments.30

All groups agreed to spend more money for patients with more severe disease, defined by seizures with falls or high seizure frequency. This is in line with previous studies that identified seizure severity and frequency as one of the main cost-driving factors for epilepsy-specific costs.11, 31 Increasing direct costs by treating severely affected patients better may in return decrease indirect costs caused by falls, comorbidities, lost productivity, and off-work days due to seizures.11, 32 It is of note, however, that all groups including physicians spent significantly less money on annual seizures, although such seizures still entail far-reaching socioeconomic consequences like unfitness of driving or bans to operate certain machines often leading to unemployment or even early retirement.31 We speculate that this observation may be a hint that respondents did not base their choices solely on socioeconomic considerations (i.e., how to minimize indirect costs) but rather favored the worst-off, such as those with the heaviest disease.6

Paradigmatically, the efficacy of a given therapeutic intervention has to be balanced against the risk of adverse effects. A recent study by Rosenow et al. identified both the prospect of seizure freedom and the avoidance of the side effect of trouble thinking clearly as the most important treatment attributes for PWEs with focal seizures with regard to ASM monotherapy.33 By minimizing the risk for socially desired answers, our results reflect this consideration only partially, as respondents were generally willing to spend more money if the fictional ASM led to seizure freedom, but the results regarding severity of adverse effects were less clear with mostly nonsignificant results. Physicians, who face the expectation to cure epilepsy, emphasized surcharges for efficacy of ASM more than for absence of adverse effects. In contrast, the control group equally balanced costs for seizure freedom and absence of severe adverse effects. Efficacy but not adverse effects of ASM had a great impact on the willingness to pay of relatives of PWEs. This may reflect their individual burden of disease, which appears to depend more on seizures than on potential adverse effects of ASM. PWEs, however, showed no significant results here, with only a tendency for seizure freedom. A potential explanation for this observation may be that we included PWEs of a tertiary epilepsy center who tend to have more severe, drug-resistant epilepsy; out of some sort of frustration caused by their own medical biography, these patients may therefore only have weighed disease characteristics instead of ASM efficacy. However, we did not assess the epilepsy syndrome or ASM history of these PWEs, which is a limitation of this study. Of note, the majority of PWEs were covered by SHI, which means that they were unaware of the true ASM costs.

On the level of the vignette-patient, two observations stood out, namely, that the control group spent significantly less money for older patients. Physicians did the same but in a nonsignificant way. Second, physicians spent less money if the patient was unemployed, with a tendency doing so in the control group. Prioritizing the young when allocating medical resources is an ethical principle based on the goal to give all individuals equal opportunity to live a normal life span.6, 34 If used alone, however, the principle ignores prognostic differences among individuals and may lead to age discrimination6—a phenomenon prevalent in both society and medical settings with damaging potential.35-37 To the best of our knowledge, there are no data available addressing whether age discrimination plays a role in ASM distribution to date. Careful further examination of this subject seems important, as bias may derive from the observation that older PWEs receive older ASMs at lower costs if their treatment was established before new ASMs were available, whereas younger PWEs are directly started on new ASMs such as lamotrigine or levetiracetam.28

Although physicians are committed to the principle of equal treatment, it is remarkable that the employment status of the fictional patient influenced the physicians. This is a particularly interesting finding because PWEs are at a high risk for unemployment or underemployment due to their disease.38 Spending more money for unemployed PWEs may in return lead to better seizure control, thus helping to reintegrate these patients in the labor market.

It remains unclear at this point how and if our findings translate to disparities in everyday care, which certainly deserves further research. Communication strategies should counteract these potential (unconscious) discrimination mechanisms. Discriminating cost allocation was not observed in PWEs or their relatives.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the respondent groups were small and may, therefore, not have been representative. This may have been especially important for the group of PWEs; as mentioned above, this group was recruited in a tertiary epilepsy center where patients tend to have more severe, drug-resistant epilepsy. However, we did not collect information on the disease or ASM history of PWEs. For the group of physicians, we decided to include only neurologists as they are most familiar with epilepsy and its treatment; over 50% were residents, and we did not assess whether they provide both inpatient and outpatient care. This group may therefore not be representative of physicians specializing in other disciplines. The control group consisted of public health students who may have their own perspectives across various aspects of health care due to their educational background, although biomedical subjects were not part of their curriculum. Moreover, they represented only one region and one university environment. The percentage of female students in public health studies is high, which is reflected by the gender distribution in our study. Although gender had no significant influence on the willingness to pay, the control group may still not be representative of the entire German lay population. This may affect the generalizability of our findings. Although we did not detect linear correlations between age and willingness to spend, it is left up to future research to examine how participants' characteristics may influence their choices. Besides, it is not clear if our findings are transferable to other chronic diseases. The dimensions we chose were broad and oversimplified (e.g., absences vs tonic–clonic seizures instead of various different seizure types) due to the limitation of the vignette design, which, however, minimizes the risk of socially desired answers that we preferred to choose over a more detailed examination of the parameters of question.

5 CONCLUSION

Rationing evolves around the question of whether the potential benefit of a medical measurement is sufficient to justify the expense.6 Although considerations of cost-effectiveness and rationing have a bad reputation in the public domain,8 our results reveal factors that influenced the respondents' willingness to accept (or not accept) certain costs for ASMs. All groups of respondents spent more money on ASMs than what is usually required in current clinical practice. This is of note as the majority of PWEs and physicians were unaware of real ASM costs. ASM efficacy generally appeared to justify higher costs, especially in severe disease. This was especially true for relatives who did not discount worse tolerability. Physicians assigned lower costs to unemployed PWEs and the control group attributed to older PWEs. Thus our study identified influencing factors that differed between the respondent groups and may contribute to an open and public discussion on rationing limited resources and break up societal taboos to reach a broader consent on the issue.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Jenny Stritzelberger, David Olmes, Peter Kriwy, Katrin Walther, and Hajo M. Hamer. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Tamara M. Welte, Stephanie Gollwitzer, Johannes D. Lang, Jenny Stritzelberger, Caroline Reindl, Stefan Schwab, and Wolfgang Graf. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Tamara M. Welte, Stephanie Gollwitzer, Johannes D. Lang, David Olmes, Caroline Reindl, Wolfgang Graf, Stefan Schwab, Peter Kriwy, Katrin Walther, and Hajo M. Hamer. Statistical analysis: Peter Kriwy. Drafting of the manuscript: Jenny Stritzelberger. Supervision: Hajo M. Hamer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any grant from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector funding agencies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

J.D. Lang served on the speakers bureau of Eisai and Desitin. H.M. Hamer has served on the scientific advisory boards of Arvelle, Bial, Corlieve, Eisai, GW, Novartis, Sandoz, UCB Pharma, and Zogenix. He has served on the speakers' bureaus of or received unrestricted grants from Amgen, Ad-Tech, Alnylam, Bracco, Desitin, Eisai, GW, Nihon Kohden, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.