Idelalisib (PI3Kδ inhibitor) therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A Swedish nation-wide real-world report on consecutively identified patients

Abstract

Objectives

We examined the efficacy and toxicity of the PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib in combination with rituximab salvage therapy in consecutively identified Swedish patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Methods and Results

Thirty-seven patients with relapsed/refractory disease were included. The median number of prior lines of therapy was 3 (range 1–11); the median age was 69 years (range 50–89); 22% had Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) >6 and 51% had del(17p)/TP53 mutation. The overall response rate was 65% (all but one was partial response [PR]). The median duration of therapy was 9.8 months (range 0.9–44.8). The median progression-free survival was 16.4 months (95% CI: 10.4–26.3) and median overall survival had not been reached (75% remained alive at 24 months of follow-up). The most common reason for cessation of therapy was colitis (n = 8, of which seven patients experienced grade ≥3 colitis). The most common serious adverse event was grade ≥3 infection, which occurred in 24 patients (65%).

Conclusions

Our real-world results suggest that idelalisib is an effective and relatively safe treatment for patients with advanced-stage CLL when no other therapies exist. Alternative dosing regimens and new PI3K inhibitors should be explored, particularly in patients who are double-refractory to inhibitors of BTK and Bcl-2.

Novelty statements

What is the new aspect of your work?

There is markedly more toxicity in our study than in the pivotal trial.

What is the central finding of your work?

Idelalisib is an effective and relatively safe salvage treatment.

What is (or could be) the specific clinical relevance of your work?

Even though the risk profile for PI3K inhibitors remains higher than for other targeted therapeutics, our data suggest that there is still a need for such agents when no other therapies exist.

1 INTRODUCTION

Despite access to new precision therapeutics such as inhibitors of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) and Bcl-2 (venetoclax), most patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) continue to relapse and require other treatment options. Idelalisib, which was approved for CLL in 2014, inhibits the activity of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase delta (PI3Kδ), which is increased in CLL cells, and induces cell death1, 2 through a mechanism that is independent of TP53 functions. As such, idelalisib represents a treatment alternative different from Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) and B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor (Bcl-2i). However, the risk of autoimmune complications3 has reduced its target group to patients who are refractory, non-tolerant to, or unsuitable for BTK and Bcl-2 targeting agents.4, 5

The pivotal phase 3 trial explored idelalisib in combination with rituximab and reported an overall response rate (ORR) of 81% with a progression-free survival (PFS) at 24 weeks of 93%.6 Grade ≥3 transaminitis occurred in 5%. Adverse events (AE) leading to study-drug discontinuation were reported in 8% of the patients, mainly due to gastrointestinal and skin side effects. These results led to FDA and EMA approvals in 2014 for relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL.

Starting in 2014, idelalisib was used in Swedish routine health care for R/R CLL but in 2017 its usage declined markedly and approached zero due to access of first generation of BTKi ibrutinib and later also Bcl-2i venetoclax. Given that progressive disease7, 8 or long-term toxicity has recently and increasingly been reported in patients receiving ibrutinib and venetoclax there is a renewed interest in PI3K inhibitors both as salvage therapy in double-refractory patients and, in eligible patients, also as a bridge to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. We therefore decided to perform a nationwide, retrospective long-term analysis of idelalisib efficacy and toxicity in a cohort of consecutively identified patients with R/R CLL.

Sweden offers a unique opportunity to identify patients through a personal identity number and registries and the majority of patients are diagnosed, treated, and followed life-long in public healthcare at the same hematology unit and hospital. External referrals are practically absent. We can therefore obtain reliable real-world data on unselected patients with lifelong follow-up to compare with data from clinical trials.9-12 This knowledge is important not only for patients and healthcare providers but also for authorities when evaluating cost-effectiveness and safety of new drugs when applied in a wider group of patients treated outside trials.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study procedure and data acquisition

This was an observational retrospective cohort study. All patients in Sweden diagnosed with CLL according to the World Health Organization criteria and treated with idelalisib after its approval in March 2014 were included. A preliminary survey revealed that from the end of 2017 when venetoclax became available and onwards the use of idelalisib became minimal. The inclusion period was therefore limited to 2.5 years, that is, from approval in March 2014 until September 2017, which also allowed long-term follow-up of our cohort. Ethics committee approval was obtained before commencement of the study (Dnr: 2015/1025-32). As this was a retrospective observational study no informed patient consent was required. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with national laws.

Patients treated with idelalisib were identified from the Swedish pharmacy registry and cross-checked with the patient file via the regional representatives of the Swedish CLL study group. Medical files were reviewed in detail from the date of diagnosis until patient's death or until the end of data collection defined as the last follow-up. Data were abstracted to case record forms (CRFs).

The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS)13 was applied to assess comorbidity other than CLL at the start of treatment. Response to treatment as well as hematological toxicity was evaluated according to iwCLL guidelines.14 Major infections and hospitalization that occurred during treatment and until 3 months after treatment termination were recorded as well as use of prophylactic antibiotics. Detailed information about treatment-related adverse events (colitis, transaminitis, and pneumonitis) was recorded.

Data from CRFs were transferred to a database and the information was systematically cross-checked and validated for accuracy, along with additional validation during the statistical analysis.

2.2 Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics such as counts, percentages, medians, and range were used to summarize categorical and continuous data. Distributional differences between groups were tested using Fisher's exact test for categorical data and the Mann–Whitney or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous data. The proportion of responses is presented together with exact (Clopper–Pearson) 95% binomial confidence intervals. Time in the analysis of PFS was calculated from date of treatment start to date of progression, date of treatment change or date of death, whichever came first. Length of overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of treatment start to the date of death. For event-free patients or patients still alive, time was calculated from treatment start to the last clinical visit date.

Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and differences between groups in time to failure/death were tested using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using the software Stata (version 17).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients

Thirty-seven patients were identified at 17 Swedish centers until September 2017. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 69 years (range 50–89). Most patients had a good performance status (54% had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 0–1) and few comorbidities (78% had CIRS score ≤6). Seventy-three percent had Rai stage III/IV. Nineteen patients (51%) had del(17p) or TP53 mutation. Additionally, five patients (14%) had del(11q). The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range 1–11). Eleven patients (30%) had previously received ibrutinib treatment.

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Median age at start of idelalisib | 69 years (50–89) | |

| Gender | Male | 22 (60) |

| Female | 15 (40) | |

| ECOG | 0–1 | 20 (54) |

| 2–4 | 14 (38) | |

| UNK | 3 (8) | |

| CIRSa | 0–5 | 29 (78) |

| >6 | 8 (22) | |

| Rai stageb | 0–I | 4 (11) |

| II–IV | 30 (81) | |

| UNK | 3 (8) | |

| Geneticsc | del(17p)/TP53 mutation | 19 (51) |

| del(11q) | 5 (14) | |

| del(13q) | 2 (5) | |

| Normal | 5 (14) | |

| UNK | 6 (16) | |

| Number of prior therapies | 0 | 0 (0) |

| 1–2 | 17 (46) | |

| 3–4 | 10 (27) | |

| ≥5 | 10 (27) | |

| Previous treatment divided into groups | FCR/FC/F | 27 (73) |

| BR/bendamustine | 25 (68) | |

| Chlorambucil | 11 (30) | |

| Alemtuzumab | 12 (32) | |

| Ofatumumab | 4 (11) | |

| Ibrutinib | 11 (30) | |

| Other agents | 4 (11) |

- Abbreviation: BR, bendamustin + rituximab; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; F, fludarabine; FC, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide; FCR, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab.

- a Scores on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) range from 0 to 56 and higher scores indicating more and severe coexisting illnesses.

- b Rai staging system: 0, low-risk disease; 1–2, intermediate risk; 3–4, high risk.

- c The most common chromosomal aberration in each of the patients.

3.2 Length of therapy and efficacy

All patients received idelalisib at a starting dose of 150 mg twice daily with (n = 28, 76%) or without (n = 9, 24%) concomitant rituximab as decided by the responsible physician. Idelalisib was continued until progression or non-tolerability. The median length of therapy was 9.8 months (range 0.9–44.8). The median time between stop of idelalisib and start of next treatment was 16.5 months (range 4.6–46.9).

The ORR was 65% (24/37): 21 partial responses (PRs) and 2 PR with lymphocytosis (PR-L) and 1 complete remission (CR). The response rates were similar in men and women and neither age nor del(17p)/TP53 mutation appeared to affect response rates. Median time to response was 5.7 months (range 1.5–22.9). Response rate was similar irrespective if patients had received prior ibrutinib (n = 11) or were BTKi naïve (n = 26) (ORR 64% and 65%, respectively). Seven out of 9 patients (78%) responded to single-agent idelalisib and 17 of 28 patients (61%) to idelalisib in combination with rituximab.

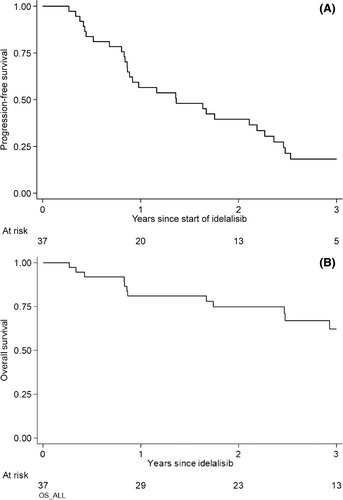

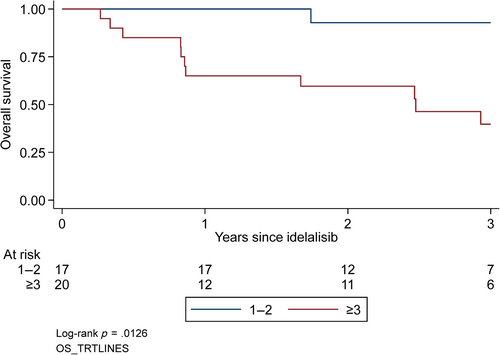

Median follow-up was 33.6 months (range 10.8–57.6) and the median PFS was 16.4 months (95% CI: 10.4–26.3) (Figure 1A). None of the baseline variables (gender, age, clinical stage, CIRS, del(17p)/TP53, del(11q), or number of previous treatment lines [1–2 and more than 3]) were significantly associated with PFS. Median OS had not been reached; the survival rate at 24 months of follow-up was 75% (95% CI: 57%–86%) (Figure 1B). OS was significantly associated with number of previous treatment lines (1–2 and more than 3) (p = .01) (Figure 2) but not with sex, age, stage, CIRS, or cytogenetics.

At 24 months of follow-up, 27% of ibrutinib pre-treated patients remained progression-free (95% CI: 7%–54%) compared to 45% of patients who were BTKi naïve (95% CI: 25%–63%) (not significant).

Also measured at 24 months of follow-up 53% receiving single-agent idelalisib remained progression-free (95% CI: 18%–80%) compared to 36% of patients who received the drug in combination with rituximab (95% CI: 19%–53%) (not significant).

3.3 Toxicity

Toxicity is listed in Table 2. Side effects (≥grade 3) occurred in 10/37 patients and included diarrhea/colitis (n = 7), transaminitis (n = 1), rash (n = 1), and pneumonitis (n = 1). Reasons for discontinuation of idelalisib were colitis (n = 8), progressive CLL (n = 7), grade 3–4 infection (n = 4), Richter transformation (n = 3), pneumonitis (n = 2), allogeneic stem cell transplantation (n = 1), mucositis (n = 1), and liver failure (n = 1). Eighty-nine percent of patients (33/37) were hospitalized during idelalisib therapy. Of those hospitalized, infection (n = 24) was the most common reason followed by AE (n = 12). Other reasons for hospitalization (different reasons for all patients) occurred in 10 patients. The most common ≥grade 3 infections were pneumonia (n = 9), febrile neutropenia (n = 4), septicemia (n = 3), and opportunistic infections (n = 5, including systemic fungal infection [n = 1] and pneumocystis pneumonia [n = 4]). Sixty percent of patients received concomitant antibiotics (all were Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis). Neither age nor CIRS, ECOG or number of previous treatment lines (1–2 and more than 3) were significantly associated with the risk of infections. The most common AEs were colitis (n = 6), diarrhea (n = 3), GI-bleeding (n = 1), heart failure (n = 1), and mucositis (n = 1).

| n (% patients) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Infections grade 3–4 | Gastrointestinal | 1 (3) |

| Febril neutropenia | 4 (11) | |

| Pneumonia | 9 (24) | |

| Septicemia | 3 (8) | |

| Opportunistic infection | 5 (14) | |

| Other infections | 2 (5) | |

| Hematologic adverse events | Anemia grade 3–4 | 0 (0) |

| Trombocytopenia grade 3–4 | 15 (41) | |

| Neutropenia grade 3–4 | 24 (65) | |

| Non-hematologic adverse events | Rash grade 3–4 | 1 (3) |

| Diarrhea/colitis grade 3–4 | 7 (19) | |

| Transaminitis grade 3–4 | 1 (3) | |

| Pneumonitis grade 3–4 | 1 (3) | |

| Use of prophylactic antibiotics | Yes | 22 (60) |

| No | 15 (40) |

Neutropenia ≥grade 3 occurred in 24 of the patients and thrombocytopenia in 15 patients but no anemia ≥grade 3 was observed. Other malignancy occurred in one patient (squamous cell carcinoma in the skin with brain metastasis).

Salvage therapy after idelalisib treatment was started in 26 patients. Regimens used were: ibrutinib (n = 15), venetoclax (n = 4), CHOP-based therapies (n = 4, all but one had Richter transformation), bendamustine + ibrutinib (n = 1), and two patients received allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Seventeen patients have died and causes of death were disease progression (n = 12), concomitant colitis and septic shock (n = 1), hemophagocytic syndrome (n = 1), myocardial infarction (n = 1), other malignancy (n = 1), and liver cirrhosis (n = 1).

4 DISCUSSION

Idelalisib, an oral inhibitor of PI3Kδ has been used in Sweden for R/R CLL since its approval in 2014 but its usage practically stopped at the end of 2017 due to access to ibrutinib and venetoclax. As patients have gradually started to relapse or experienced long-term complications from BTKi or Bcl-2i a renewed interest for PI3K inhibitors has recently been observed. This real-world study investigated the efficacy and toxicity of idelalisib when used in a heavily pretreated group of consecutive patients with advanced-stage CLL in a well-defined region (Sweden).

The real-world cohort reported here showed a slightly lower ORR (65%) compared to that of the pivotal trial (81%)6 and its extension report (86%).15 Baseline age, number of prior therapies, and stage were similar but, notably, the real-world cohort had a lower proportion of patients with CIRS >6 (22%) than in the pivotal trial (85%).6 We could not confirm the pivotal study findings,6, 15 that unfavorable cytogenetics was associated with a lower response rate which may be due to the limited size of our real-world population.

The ORR rate of 65% is largely in line with other real-world reports. Hoechstettera et al reported an ORR of 70% on a German population.16 Front-line treatment might contribute to a higher ORR, with an ORR of 81% as in reference 17 and 100%18 reported in such populations previously.

The median PFS (16.4 months) in our cohort was similar to that of the initial multicenter phase 1 study (15.8 months).19 Other investigators have reported a PFS of 20.3 months15 to 22.9 months20 and 25.6 months.21 The diverging results are probably explained by heterogeneity among study populations, emphasizing the importance of real-world studies that are conducted on consecutive patients from well-defined areas.

Even though there was no difference in ORR between patients who were pre-treated or not with ibrutinib, PFS was, not unexpectedly, numerically shorter among BTKi pre-treated patients. This suggests that late usage of idelalisib shall be mainly used as bridging to alternative more efficacious regimens.

While idelalisib is often used in combination with rituximab, some of our patients received idelalisib as a single agent, as decided locally by the responsible physician. The number of patients was too few to draw conclusions on the value of rituximab.

Grade ≥3 infections (65%) and pneumocystis pneumonia (11%) were more common in our real-world cohort, despite prophylactic antibiotics in 60% of patients, than in the pivotal trial (21% and 4%, respectively) in which prophylactic antibiotics was not mandatory.6 In a real-world study by Rigolin et al.20 grade ≥3 infections occurred in 30% of the patients. Unfortunately, usage of prophylactic antibiotics was not reported.

Furthermore, despite the low proportion of patients with CIRS >6, more patients discontinued treatment in our cohort (43%) due to AE compared to the pivotal trial (8%).6 However, Mato et al17 also reported high discontinuation of idelalisib (58/62 patients), mainly because of toxicity (45%) and progression (28%).

The major limitations in our study include its retrospective design, its limited size, and that data were generated several years ago before BTKi and Bcl-2i became widely available. However, the study included consecutive patients and the risk that any patient has been missed is considered low.

In summary, our real-world analysis on consecutively idelalisib-treated patients with advance-phase CLL in Sweden shows that the drug is effective but guidelines to mitigate infection and colitis are needed. Even though the risk profile for PI3K inhibitors remains higher than for other targeted therapeutics,22, 23 our data suggest that there is still a need for such agents when no other therapies exist. PFS is regarded as clinically meaningful. Additional studies are warranted on how to improve safety by alternative dosing strategies and using next-generation PI3K inhibitors.24, 25

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Agnes Mattsson, Sandra Eketorp Sylvan, Anders Österborg, and Lotta Hansson designed the study, analyzed the results, and wrote the draft manuscript. Hemming Johansson performed the statistical analyses and wrote the statistical part of the manuscript. Agnes Mattsson, Per Axelsson, Fredrik Ellin, Christian Kjellander, Karin Larsson, Birgitta Lauri, Catharina Lewerin, Christian Scharenberg, Love Tätting audited the medical files and completed the CRFs for included patients. Agnes Mattsson, Sandra Eketorp Sylvan, Anders Österborg, and Lotta Hansson interpreted the results. All authors reviewed and edited revisions of the manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from AFA Insurance (Ref no: 130054), the Stockholm County Council (SLL/ALF) (Ref no: 20150070), Felix Mindus Foundation, Senior Clinical Research Position (SLL/KI) 2018/2019 (K2894-2016), The Swedish Cancer Society (Ref nos: 150930, 160534), the Cancer and Allergy Foundation, The Cancer Society in Stockholm, and the King Gustaf V Jubilee Fund, the Karolinska Institutet Foundations, and Gilead Sciences Nordic Fellowship Program. We thank Ms Leila Relander for editorial assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Lotta Hansson has received research grant support from Gilead and Janssen-Cilag and honoraria from Abbvie. Anders Österborg has received research grant support from Beigene, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Celgene, and Janssen-Cilag. Love Tätting has received honoraria from Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb; study board Takeda. The other authors did not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Files with original data are available upon request from the corresponding author.